By Martin K.A. Morgan

By mid-August 1944, roughly one month before the now-famous Operation Market Garden, the U.S. Army’s 82nd Airborne Division had been fighting off and on for over a year. The previous July, the division had gone into combat for the first time as a part of Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily. Two months later, in September 1943, the 82nd supported the Operation Avalanche landings at Salerno on the west coast of Italy.

With the exception of the 504th Parachute Infantry, one of the division’s three organic parachute regiments, the 82nd departed Italy for England in December to prepare for the upcoming Normandy invasion. The 504th, meanwhile, remained in Italy to rest and refit and made the XI Corps’ amphibious landings at Anzio on January 22, 1944.

Although the 504th joined the rest of the division in England in March, it had by then been temporarily replaced by the 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment. In the predawn hours of June 6, 1944, the division (minus the 504th) parachuted into the marshes and hedgerows of the Cotentin Peninsula behind a stretch of coastline that would forever be known as Utah Beach. During the next 35 days, the 82nd experienced intense combat in battles at places with names such as Ste.-Mère-Église, Hill 30, and a little stone bridge at La Fière.

By the third week of July 1944, the 82nd was back in England. Upon returning, all of the division’s troopers were given short furloughs before getting down to the important business of recovering from the aftereffects of the Normandy fighting. Since the division had suffered more than 5,000 casualties, a large number of replacements had to undergo jump training so that the ranks of its combat-depleted battalions could be brought up to strength.

In August, the division’s combat veterans began the process of transmitting the experience they had earned in Sicily, Italy, and France to the young replacement troopers joining the 82nd.

Also that month, the division’s leadership underwent a change. Until then, the 82nd Airborne had been under the command of Maj. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway. Following the Normandy campaign, though, Ridgway was promoted to the rank of lieutenant general and given command of the XVIII Airborne Corps.

Ridgway was not the only one to receive an additional star that month. His former assistant division commander, 37-year-old James M. Gavin, was promoted to the rank of major general and designated the new commanding officer of the 82nd Airborne. For Gavin and the rebuilt strength of his division, new campaigns were on the drawing boards and would soon begin.

Several new airborne operations were proposed in August. In each case, the men of the 82nd prepared themselves for combat only to learn that rapidly advancing ground forces had overrun the objectives they were to have assaulted from the air. Following the breakout from the Normandy beachheads in July, Allied armies drove forward much more swiftly than had been anticipated. Lt. Gen. George S. Patton’s Third Army quickly overran Brittany, Allied forces headed by Maj. Gen. Philippe LeClerc’s French 2nd Armored Division liberated Paris on August 25, and from there the British Second Army surged through Belgium to the Dutch frontier.

Although Allied armies had penetrated deep into German-held territory with stunning speed, as September 1, 1944, approached, those armies were still being supplied off the Normandy beaches some 300 miles behind them. As lines of supply grew longer and longer, major logistical problems began to haunt the Allies.

Eisenhower Sides With Montgomery Over Patton

In early September, British Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery approached General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, with a plan to push the northern flank of the Allied front forward to secure the channel ports of the Low Countries. This move would, in theory, open those ports, shorten the lines of supply, and make it possible for the British XXX Corps to force the flanks of Germany’s defenses, cross the Rhine River, and drive into the heart of the Reich. The plan even proposed a swift capture of Berlin by Allied armies and a swift end to the war.

Years later in his memoirs, Eisenhower remembered, “Montgomery suddenly presented the proposition that, if we would support his 21st Army Group with all supply facilities available, he could rush right on into Berlin and, he said, end the war.” Although it meant slowing Patton down—if not stopping him altogether—Eisenhower approved Montgomery’s plan.

Patton was naturally incensed. Ike’s naval aide, Captain Harry Butcher, noted that a war correspondent told him “that officers and personnel of Patton’s Third Army are burned up because they feel the British have been favored by General Ike with transport and permitted to advance while the Americans in the Third Army were stalled because of lack of gasoline. He said he had talked with junior officers in Patton’s army and some had said, ‘Eisenhower is the best general the British have.’”

To secure the way for General Brian Horrocks’ XXX Corps’ overland thrust toward the Rhine, Montgomery recommended the deployment of the various divisions of Lt. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton’s First Allied Airborne Army. According to the Montgomery plan, these divisions would be dropped in broad daylight up to 64 miles behind enemy lines in Holland where they would have to quickly seize objectives essential to the success of the battle.

Code named Market, the First Allied Airborne Army’s role in the operation would be to secure bridges over major waterways in the vicinity of Eindhoven, Nijmegen, and Arnhem. With those bridges securely in the hands of Allied airborne forces, the British XXX Corps—led by armor—would advance from its front lines along the Albert Canal in Belgium—first to Eindhoven, the southernmost of the three cities. From there, XXX Corps—the Garden portion of the operation—would continue north to Nijmegen and, finally, on to Arnhem where it would cross the farthest bridge over the Lower Rhine River.

Objectives of the 82nd Airborne Division

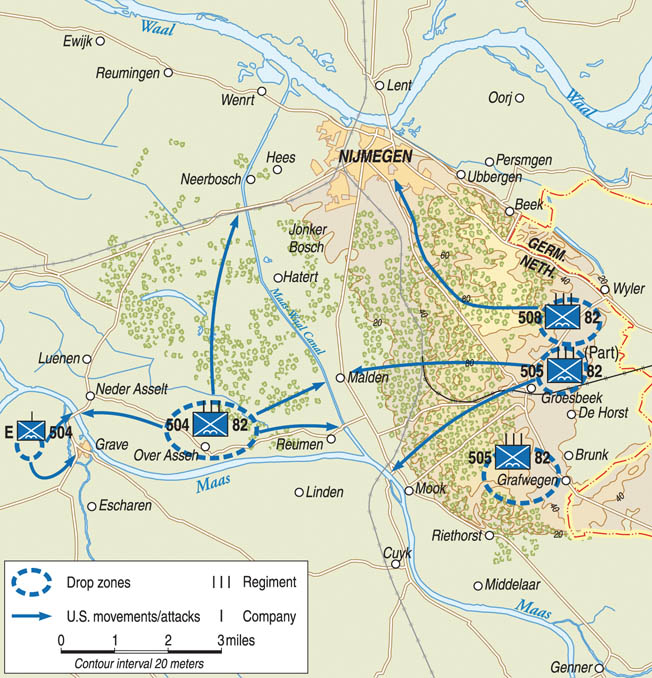

Because of where they were based in England, the British 1st Airborne Division and the Polish Independent Parachute Brigade were best positioned for the assault on Arnhem. Since Maj. Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor’s 101st Airborne Division was based at a series of airfields west of London, it was assigned the southern bridges near Eindhoven. The job of securing the bridges in the center was given to Maj. Gen. “Jumpin’ Jim” Gavin’s 82nd Airborne.

In his 1978 book On to Berlin, Gavin described what his division would have to do: “The mission assigned to the 82nd Airborne Division was to seize the long bridge over the Maas (Meuse) River at Grave, to seize and hold the high ground in the vicinity of Groesbeek, to seize at least one of the four bridges over the Maas-Waal canal, and finally to seize the big bridge over the Waal (Rhine) at the city of Nijmegen.”

Although Gavin necessarily focused on what was specifically required of the 82nd, two issues concerned him: the strength of the opposition and the British 1st Airborne’s attack plan. To him, the plan for Market seemed more akin to a peacetime exercise than an actual war plan. Intelligence reports indicated that the 82nd Airborne would face strong enemy forces; a regiment of Waffen-SS panzergrenadiers was known to be in Nijmegen, and a German armored unit was supposedly concealed in a nearby forest called the Reichswald.

It was also known that 29 heavy and 88 light antiaircraft weapons were deployed around the city. “It was assumed that the [antiaircraft] crews would be prepared to fight as infantry,” Gavin remembered in On to Berlin. That was an assumption that the 82nd would later learn the Germans had also made.

For their part, the Germans—considering the heavy losses they had suffered a few months earlier during Operation Cobra, the Allies’ breakout from Normandy—were about as well prepared as they could be. In charge of the defenses in the West was Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, whom Hitler had recalled from retirement. As many divisions, regiments, battalions, tanks, and guns as could be found were patched together and transported to Holland to dig in for an expected Allied attack.

These units and fragments of units included the Fifteenth Army, First Parachute Army, II Panzer Corps (9th and 10th SS Panzer Divisions), LXXXVI Corps, and a number of infantry divisions (such as the 84th, 85th, 89th, 176th, and 719th Infantery Divisions). Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine (Navy) formations, antiaircraft batteries, and SS units, too, were thrown into the mix. All were badly understrength, but all were ready for one final, do-or-die battle.

On Friday, September 15, the men of the 82nd Airborne were moved to and sequestered at their respective airfields. The entire next day was spent preparing weapons, distributing ammunition, and reviewing maps and aerial reconnaissance photographs—much as they had done prior to the June jump into Normandy.

“The Great Glider Armada”

On Sunday, September 17, Market Garden began. At each of the 82nd Airborne airfields, the men were up before daylight, busily trucking equipment bundles and otherwise making final preparations for the jump. Thirty years later, Gavin described what the men carried: “Because of our experiences in Normandy, the troopers loaded themselves with all the ammunition and antitank mines they could carry. Having checked personal loads of all the troopers in each regiment, we decided that about 700 individuals could each carry an antitank mine apiece.

“In addition, every trooper who could get his hands on a pistol carried one as well as a rifle. So overloaded were they that one or two troopers stood beside the steps of the C-47s and helped boost the others up the steps and into the planes.”

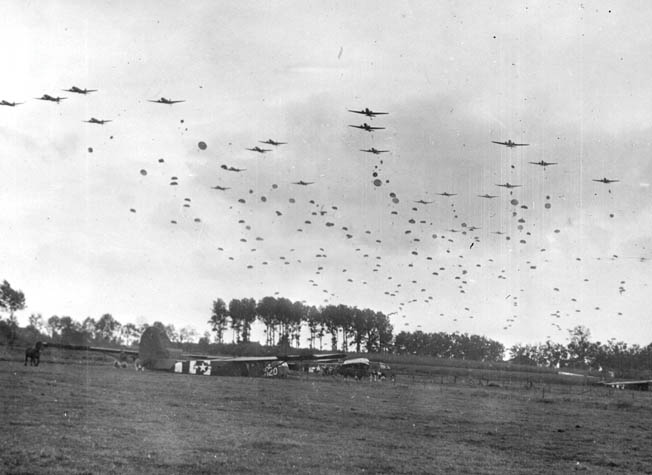

Dawn on September 17 revealed a cloudless sky and moderately warm temperatures—the weather was perfect. That morning, a total of 1,545 Douglas C-47 troop transports and 478 Waco and Horsa gliders took off from 24 airfields from Dorset to Lincolnshire. After taking off and forming up, the transport formations proceeded over the English Channel under the protection of 1,130 fighter escort aircraft. The division was carried to Holland that day by 480 C-47s from the 50th and 52nd Troop Carrier Wings of the IX Troop Carrier Command.

The aerial armada carrying and protecting Brereton’s First Allied Airborne Army was so immense that it literally filled the sky. The next day, the London Daily Express described the spectacle: “Thousands of people on England’s coast yesterday saw the great glider armada streaming out to sea toward Holland. For an hour and a half, from 11 am to 12:30 pm, the fleet filled the skies. So great was the roar that no one on the coast could use the telephone until the planes had passed.”

The 82nd Airborne’s three parachute infantry regiments (PIR)—the 504th, 505th, and 508th—would be leading the initial assault of the Nijmegen element of Operation Market by jumping into three primary drop zones (DZ) designated O, T, and N. Drop Zone O, located east of the city of Grave on the east bank of the Maas River, would be the 504th’s DZ.

Drop Zone T, north of the city of Groesbeek, would be the 508th’s DZ, and Drop Zone N, south of Groesbeek, was where the 505th would land. One part of their mission would be to secure and defend the drop zones to make it possible for supporting parachute and glider units to make subsequent landings.

In addition to the primary drop zones, E Company, 504th PIR, would assault a special drop zone on the west bank of the Maas River west of Grave. Dropping on the west bank, it would be able to assist the other 504th rifle companies on the east bank during the assault on the Maas River Bridge.

Landing in Holland

The 82nd Airborne’s Pathfinder team, led by Lieutenant G.W. Jaubert, jumped on DZ O near Overasselt at 12:47 pm. Right behind it came the 82nd’s vanguard regiment that morning––Colonel William E. Ekman’s 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment. Not the kind of commander to lead from the rear, General Gavin was jumping with Ekman’s 505th.

Through the open door of the C-47 carrying his command group, Gavin personally observed the incredible procession of aircraft and described what he saw: “As far as one could see, the sky was filled with planes and gliders, and as we neared the coast of Europe, we could see the fighter-bombers flying back and forth over the land beneath us, looking for antiaircraft guns and enemy weapons to knock out.”

On another C-47 nearby, 24-year-old Sergeant Thomas J. Blakey of A Company, 505th, was admiring the same sight. As he later remembered, September 17 was a “beautiful sunny summer afternoon.” He had taken off earlier that morning from RAF Saltby, the airfield in Leicestershire, in a Douglas C-47A from the 50th Troop Carrier Squadron/314th Troop Carrier Group. A veteran of the Normandy campaign, Blakey was about to make his second and final combat parachute jump of the war.

A few minutes after the Pathfinders jumped, the 505th PIR’s C-47s approached from the west toward Drop Zone N. General Gavin recalled the final approach to the DZ: “Everything that I had memorized was coming into sight. The triangular patch of woods near where I was to jump appeared under us just as the jump light went on.”

At 1 pm, just 13 minutes behind Jaubert’s Pathfinder team, the men of the 505th began jumping. On Gavin’s C-47, all 18 men went out the door “without a second’s delay.” Gavin recalled, “We seemed to hit the ground almost at once. Heavily laden with ammunition, weapons and grenades, I had a hard landing while the parachute was still oscillating. At once we were under small-arms fire coming from a nearby woods. I took my .45-caliber pistol out of its holster and laid it on the ground beside my hand.”

The M1911A1 .45-caliber pistol, created before World War I, was a weapon that came in handy for a number of troopers at Drop Zone N that day. Remembering how German antiaircraft guns in Ste.-Mère-Église had fired on descending paratroopers during the Normandy drop, a number of 505th men drew their .45s and began firing at the German gunners as they drifted downward under their open parachute canopies. Although the men engaging these big antiaircraft guns with their pistols could not have expected their fire to be particularly effective, they must have been pleasantly surprised when most of the German crews broke and ran.

With his personal .45 close at hand and with German small-arms fire sweeping over the drop zone, Gavin worked to free himself from his parachute: “I quickly began to take my [M1 Garand] rifle out from under the reserve chute, and I got out of the parachute harness while I lay on the ground. The moment I had my equipment off and my rifle ready to use, I replaced my pistol in the holster and ran over toward the woods.”

While most high-ranking airborne officers jumped armed with M1A1 carbines or pistols, Gavin always jumped armed with the weapon that most privates carried—the 9.5-pound M1 Garand rifle. For the Market jump, he also wore the airborne’s new jump uniform, which consisted of an M1943 field jacket and a pair of M1943 trousers with heavy canvas reinforced pockets. Although he was by then a two-star general, Gavin wore the same M2 parachutist’s helmet he had worn in Normandy that still carried the single star of a brigadier general.

The 505th was on the ground 12 minutes after it began jumping. Lt. Col. Edwin A. Bedell’s 307th Airborne Engineer Battalion jumped next, followed at 1:15 pm by Colonel Reuben Tucker’s 504th spilling out over Drop Zone O; it took the 504th a mere four minutes to complete the jump.

Next was Colonel Roy Lindquist’s 508th Parachute Infantry, which began jumping over Drop Zone T north of Groesbeek at 1:26 pm. The 508’s assignment was to seize about six miles of territory—from Nijmegen through Wyler to Groesbeek. It was also to assist in taking the bridges over the Maas-Waal Canal at Hatert and Honinghutje, plus secure two glider landing zones. It was a big job, but one that Lindquist was confident his men could perform.

The 376th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion

Two minutes after the last of the 508th men were on the ground, Lt. Col. Wilbur Griffith’s 376th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion began parachuting into Drop Zone N, the last unit of the division to jump on September 17.

According to Gavin, bringing the 376th in on the first day of Market was an “experiment.” The division’s leaders reasoned that the first opposing units the Germans would potentially commit against the Nijmegen-Grave landings would be ad hoc formations of soldiers on furlough and local home guards. The 82nd’s staff further reasoned that accurate field artillery fire would keep those formations far from the American parachute infantry assembling on the drop zones.

For that reason, the 376th would jump as a part of the initial assault with 12 M1A1 75mm airborne howitzers. When mated with the M8 Airborne Carriage, the M1A1 howitzer could be disassembled and packed into nine paracrates. Each of the nine crates could be dropped with its own parachute, and once on the ground airborne artillerymen could reassemble the weapon and begin firing.

One of the men who jumped with the 376th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion that day was 26-year-old 1st Lt. Alphonse J. Czekanski. The son of Polish immigrants, Czekanski had enlisted in the U.S. Army in March 1940. Interestingly, by 1944 fate had made him a participant in some of the most significant events of World War II. He was serving as a corporal in Battery B, 11th Field Artillery Regiment, stationed at Schofield Barracks in Hawaii on December 7, 1941, when the Japanese attacked the American Pacific fleet anchorage at Pearl Harbor.

Within a few months of the attack, he was attending Officer’s Candidate School at Fort Benning, Georgia, and received his commission as a second lieutenant on August 27, 1942. The following month, Czekanski attended jump school and became a paratrooper. Because of his previous experience in the field artillery, he was assigned to the 376th shortly before it deployed to North Africa in April 1943. Thereafter, he jumped with the 82nd Airborne during Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily in July 1943, and then landed at Anzio with the 376th in January 1944.

In the predawn hours of June 6, 1944, he jumped with the 82nd Airborne into Normandy and spent the next 35 days in combat there. By September 1944, Czekanski was a first lieutenant in D Battery, 376th, the battalion’s antiaircraft/antitank battery. Holland would be his third combat jump.

Soon after Czekanski jumped over Drop Zone N at approximately 1:33 pm on September 17, things began to go wrong. As he descended under his open parachute canopy, he was struck in the back of the head by a 300-pound equipment bundle. The force of the blow knocked him unconscious, and because he did not have control of his chute he landed on the roof of a barn, breaking one of his legs. Still unconscious, he rolled off the roof and dropped two stories to the ground below, breaking his other leg. He was later evacuated to England and then, in November, home to the United States. Though he had survived his third and final combat jump, for him the war was over.

Despite numerous other injuries suffered on the jump, the 376th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion was quick to swing into action on the drop zone; the battalion’s first howitzer was assembled and ready to fire within 20 minutes. Four hours after the drop, eight of the 376th howitzers were dropping shells on enemy positions. Although four of the battalion’s 75s were damaged on the drop, the 376th set up a 360-degree perimeter with the eight guns available. One crew even hauled its howitzer 1,000 yards by hand to reach a more advantageous firing position.

After the last C-47s flew off and the 82nd Airborne Division was on its own, it was not long before General Gavin began to take inventory of his assets on the ground; 7,250 82nd Airborne paratroopers had jumped in the vicinity of Grave and Groesbeek that afternoon. It was soon apparent that the jump had gone well. As Gavin later described, “Early indications were that the drop had been unusually successful. Unit after unit reported in on schedule and with few exceptions all were in their preplanned locations.”

Late that afternoon, Gavin began making the rounds of his division. By then, he had a jeep on the ground and proceeded from Drop Zone N north toward Groesbeek and beyond. The first unit he encountered was the 376th. Gavin soon found that the battalion’s commanding officer, Lt. Col. Wilbur Griffith, had broken his ankle on the jump and was being moved about in a wheelbarrow. When Griffith saw Gavin approaching, he laughed, saluted, and said, “General, the 376th Field Artillery is in position with all guns ready to fire.”

It was true. During the first 24 hours on the ground in Holland, the 376th fired 315 rounds and was “most effective” at keeping enemy units away from the drop zones. In addition to the valuable fire support that the battalion’s howitzers provided during the first critical hours of the operation, 376th troopers also captured 400 German enlisted men and eight officers. General Gavin’s “experiment” with parachute field artillery had worked well.

First Assaults on the Bridges

Upon assembling in their drop zones, 82nd troopers moved quickly to capitalize on the element of surprise and capture their primary objectives: the Maas River Bridge at Grave, the four bridges spanning the Maas-Waal Canal, and the Waal River Bridge at Nijmegen.

The Maas Bridge at Grave was captured by E Company, 504th PIR, about two hours after landing. Responsibility for taking the canal bridges belonged to the 504th PIR’s 1st Battalion, which swiftly advanced on the objectives from Drop Zone O.

The southernmost bridge at Molenhoek (known to the paratroopers as Bridge #7) was captured intact by troopers from B Company, 504th, as well as by elements of the 505th PIR advancing from the direction of Groesbeek. As troopers from the 504th, 505th, and 508th approached the two bridges in the center—Bridge #8 near Malden and Bridge #9 near Hatert—they were just in time to see them both blown sky high by retreating German soldiers.

Bridge #10 near Honinghutje, the largest of the canal bridges, was the only one between Grave and Nijmegen capable of bearing the weight of tanks. Accordingly, capturing it intact was of the utmost importance. However, a network of pillboxes, trenches, and barbed wire defended its approaches. That night, troopers from Colonel Roy Lindquist’s 508th PIR moved into positions and commenced an attack at first light on Monday, September 18.

At 10:30 that morning, the Germans set off demolition charges on the railroad bridge running next to Bridge #10, destroying it and weakening Bridge #10 to the point that it could not be used after its capture. Suddenly, Bridge #7 at Molenhoek was priceless real estate.

Paratroopers from the 508th made early attempts to seize the 1,960-foot-long highway bridge at Nijmegen on September 17 but were thwarted by a superior German force. They did, however, manage to locate and deactivate demolition equipment that otherwise could have been used to blow the bridge.

The paratroopers were soon locked in a furious firefight with the German soldiers defending the south end of the bridge. That defense was resolutely fought, and a stalemate followed that would not be broken for three more days.

Stunned, the Germans failed to immediately mount their customary counterattacks in the wake of the largest airborne-glider operation of the war. After nightfall on the 17th, a train filled with German troops attempting to escape rolled out of Nijmegen but was stopped by the 505th’s reserve battalion, which ended its journey with a bazooka, rifles, and machine guns. The surviving Germans fled into the woods but were soon rounded up by the paratroopers.

Landing on German Infantry

D+1 (Monday, September 18) saw more than just the struggle to capture Bridge #10 and the stalemate in front of the Nijmegen Bridge. German counterattacks from the direction of the Reichswald (as forewarned by members of the Dutch underground) and the city of Wyler (just over the border in Germany itself) were thrusting westward toward Groesbeek. Because there were several gaps in the 505th’s line to the east of the town, those German counterattacks threatened to overrun DZs T and N, which were soon to become glider landing zones.

That morning, another large air armada departed from bases in southern England carrying the first wave of 82nd Airborne gliders. This force consisted of additional divisional artillery in the form of the 319th and 320th Glider Field Artillery Battalions and the 456th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion. The gliders were also carrying the 307th Medical Company, the 80th Airborne Anti-Aircraft/Anti-tank Battalion, and the division’s signal company, as well as additional elements of the 307th Airborne Engineer Battalion. With German infantry swarming out of the Reichswald toward the landing zones, nothing could be done to warn the approaching gliders.

Shortly before 2 pm, the great aerial formation of 450 C-47s towing 450 gliders could be seen approaching from England. General Gavin described what happened next: “The drone of the engines reached a roar as they came directly over the landing zones. I experienced a terrible feeling of helplessness. I wanted to tell them that they were landing right on the German infantry.

“Soon they were overheard, and the gliders began to cut loose and start their encircling descent. As they landed, they raised tremendous clouds of dust, and the weapons fire increased over the area. Some spun on one wing, others ended up on their noses or tipped over as they dug the glider nose into the earth in their desire to bring them to a quick stop.”

The Army’s official history notes, “Beginning at 1300 [hours], after the troops had made a forced march of eight miles from Nijmegen, the attack by Lt. Col. Shield Warren’s 1st battalion [508th PIR] might have stalled in the face of intense small-arms and flak-gun fire had not the paratroopers charged the defenders at a downhill run. At the last minute, the Germans panicked. It was a photo finish, a ‘movie thriller sight of landing gliders on the LZ as the deployed paratroops chased the last of the Germans from their 16 20mm guns.’ The enemy lost 50 men killed and 150 captured. Colonel Warren’s battalion incurred but 11 casualties.”

Under intense German small-arms fire, some 82nd Airborne glidermen were seen running from their engineless aircraft and firing on the enemy, while others were struggling to free artillery pieces and jeeps from their gliders. Despite the intense enemy fire, most of these newly arrived units were miraculously intact, bringing with them a large quantity of valuable equipment. They delivered 135 jeeps and eight M1 57mm antitank guns—weapons that would prove vital in the event that German armor appeared in the area.

The gliders also landed 30 additional M1A1 75mm pack howitzers, which were quickly brought into action alongside the M1A1s that had landed with the 376th the day before. Before September 18 was done, the 82nd Airborne Division had a total of 41 75mm howitzers firing in support of its operations.

Minutes after the glider landings were complete, 135 Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers thundered in over the area, dropping parachute bundles containing much needed supplies. While some of the supply bundles landed behind German lines, the paratroopers ultimately recovered approximately 80 percent of them.

The Capture of Nijmegen Bridge

As the stalemate at Nijmegen continued the following day (Tuesday, September 19), advance elements of the Guards Armoured Division (from the Garden element of the operation) entered the 82nd Airborne’s sector near Grave. With the road to Nijmegen clear before it, units of the British XXX Corps moved up to contribute their firepower to the fight against the German defenders.

Late that afternoon, General Gavin had a conference with British Lt. Gen. Frederick M. “Boy” Browning, deputy commander of the First Allied Airborne Army. During the meeting, Browning warned Gavin, “The Nijmegen bridge must be taken today—at latest tomorrow.” To Gavin, the hour was becoming “desperate.”

By then, Maj. Gen. Robert F. Urquhart’s British 1st Airborne Division had been cut off in Arnhem for three days and yet the Nijmegen Bridge was still in enemy hands. If XXX Corps was to get through to relieve the 1st Airborne Division, that bridge had to be taken.

To break the deadlock, Gavin came up with a bold plan: a force of parachute infantrymen would cross the Waal River in engineer boats borrowed from the British, a smokescreen masking their advance. Upon reaching the opposite bank, the force would then attack the Nijmegen Bridge from the rear, outflanking its defenders. During the attack, British tanks from XXX Corps would provide fire support to suppress the German 88mm guns on the east bank.

After capturing the bridge, 82nd Airborne soldiers would cross it and secure a bridgehead on the opposite bank, allowing XXX Corps to begin its advance to relieve Urquhart’s beleaguered paratroopers in Arnhem. Gavin ordered the attack for the following day, September 20, and selected Lt. Col. Reuben Tucker’s 3rd Battalion, 504th PIR, to lead it.

The night was spent locating and assembling the canvas and wood-slatted engineer boats that would carry the 504th troopers across the Waal. Only 26 of the flimsy craft were available, arriving only 20 minutes before the attack was due to kick off. (Those who have seen the 1977 film A Bridge Too Far will recall Robert Redford’s character, Major Julian Cook of the 3rd Battalion, saying to his dismayed men, “What did you expect—destroyers?”)

Fifteen minutes before H-hour, American artillery opened up against the Germans on the opposite side of the river.

At 2 pm, someone yelled, “Go!” and the paratroopers wrestled the boats down to the water’s edge and launched them one mile west of the bridge. A shortage of paddles meant some men had to row with their rifles. Each 19-foot-long boat carried 13 troopers from I Company, 504th PIR, and three troopers from C Company, 307th Airborne Engineer Battalion; there were 416 men in the first wave.

A smokescreen was laid down to hide the river assault from German eyes. As the overloaded boats entered midstream, a breeze blew the smokescreen away, revealing them to enemy guns on the east bank.

Despite the enemy fire and the difficulties they encountered in maneuvering the boats in the river’s strong current, the troopers reached the opposite shore and deployed for action, but the enemy’s artillery, machine guns, and 20mm antiaircraft guns were so destructive that of the 26 boats in the first wave only 11 returned for the second and subsequent five crossings. The human cost was high, too: 48 men from the 504th and the 307th were killed during the crossing.

The water-borne paratroopers were aided in their assault by the timely arrival of British tanks from the Guards Armoured Division’s Coldstream Guards Group, which pummeled German positions with their main guns.

In the intense firefight that followed on the east bank, the paratroopers battled the German defenders at close quarters with rifles, bayonets, and grenades. Though the battle was savagely fought, the paratroopers had momentum that carried them on to the objective. Troopers from I Company, 504th, flanked the highway bridge while men from the 504th’s H Company flanked the railroad bridge.

Simultaneously, troopers from the 505th PIR launched an attack from the Nijmegen side of the bridge. The combined assault overwhelmed the defenders. Trapped on the bridge that they had been defending since September 17, German soldiers were decimated by the furious small-arms crossfire. After the fight concluded, 267 dead Germans littered the bridge.

Breaking the German Counterattack

With the Nijmegen Bridge now open for Allied traffic, the British Guards Armoured Division crossed it and began the drive north to relieve their countrymen at Arnhem. The 82nd men then took up positions to defend the bridgehead they had fought so hard to secure.

All the while, Gavin kept an eye open for any reports of a German counterattack coming out of the Reichswald; he didn’t have long to wait. On the morning of September 20, a heavy artillery barrage preceded a German ground attack against 82nd forces in the Mook area and threatened the Heuman Bridge. Speeding there by jeep from Nijmegen, Gavin asked the Coldstream Guards for help, which they were happy to provide.

As Cornelius Ryan wrote in his book A Bridge Too Far, “Shifting his forces back and forth like chess men, Gavin held out and eventually forced the Germans to withdraw. He had always feared an attack from the Reichswald. Now Gavin and the Corps commander, General Browning, knew that a new and more terrible phase of the fighting had begun. Among the prisoners taken were men from General [Eugen] Meindl’s tough II Parachute Corps. [Field Marshal] Model’s intention was now obvious: key bridges were to be grabbed, the corridor was to be squeezed, and Horrocks’ columns crushed.”

The next day, September 21, the men of C Company, 504th, were in defensive positions near the city of Oosterhout when the Germans launched a counterattack. The enemy force of approximately 100 infantry supported by a half-track and two panzers surged forward in a drive to recapture the Nijmegen Bridge.

Without being ordered to do so, a C Company soldier, Private John R. Towle, left his foxhole and ran 200 yards forward to a position on an exposed dike roadbed. From there, Towle fired his M1A1 rocket launcher at both tanks, inflicting damage that forced both of them to turn back. When he drew fire from a nearby house being used by nine Germans as a strongpoint, Towle fired a single rocket into the house, killing all nine of the enemy. He then rushed forward through enemy fire again to get into a more advantageous position to fire his bazooka at the advancing half-track.

Towle was kneeling and aiming his bazooka when fragments from a German mortar round fatally wounded him. He had singlehandedly broken up the enemy counterattack, which had posed a serious threat to the security of the Nijmegen bridgehead. For his self-sacrificing bravery, Private John R. Towle was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

September 21 turned out to be an important day at Nijmegen, where the fight for the highway and railroad bridges continued. Lt. Col. Ben Vandervoort’s 2nd Battalion of the 505th PIR, assisted by British tanks and infantry, continued to pound the German defenders guarding the approaches to the south end of the highway bridge. The Germans, faced with mounting pressure on the Nijmegen bridge, decided to destroy it.

On Saturday, September 23, the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment arrived in Holland. Originally scheduled to land on D+1, poor weather conditions delayed the 325th in England for five days. Without delay, General Gavin fed the 325th into battle.

Success For the 82nd, Failure For Operation Market Garden

Although the Nijmegen bridge had been captured and held by the 82nd and British armor only after some of the most desperate fighting of the entire war, other Allied elements were not so fortunate. British paratroopers at Arnhem had been cut off and decimated; Horrocks’ XXX Corps had fallen far behind in its timetable to reach the beleaguered paratroopers. And the 1st Polish Parachute Brigade that was supposed to have bolstered British troops on the ground was delayed departing England because of fog; the Poles did not arrive in Holland until September 21. By then it was too late to salvage Market Garden.

The relief column never reached Arnhem, and Operation Market Garden ultimately failed to deliver the swift and decisive victory that Field Marshal Montgomery had envisioned. That failure came at a high price with the Allies suffering more than 17,000 dead and wounded. American casualties alone amounted to a total of 3,974—1,432 of which were “All Americans” from the 82nd Airborne Division. The troopers of the 82nd remained in Holland until mid-November.

The Allied generals did not waste time brooding over the failure of Market Garden. The port of Antwerp had to be opened to shorten the lifeline of supplies coming from Britain. Plans for a new thrust against Germany’s western defenses were already in the works, an operation designed to envelop the Ruhr, Germany’s industrial heartland, and a massive assault to penetrate Hitler’s formidable West Wall fortifications.

“American paratroopers stream from their Douglas C-47 transport aircraft and begin their descent to an open field near the town of Grave, Holland. Gliders already litter the area after landing to disgorge men and supplies.”

Is wrong, should be:

23rd of September at 16:00 – 1 Para Bn and the remainder of 3 Para Bn dropped in area of GRAVE (1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade)

Please correct.

The city of Grave lies south of Nijmegen. American forces captured it on 17 September. The Polish Brigade dropped to the north, closer to Arnhem at Driel on the 21st. The gliders shown are American C4-GAs (the wing supports make it clear) with American markings. I believe the Poles used British made Horsa gliders, and while I’m not sure how their gliders were marked, I would doubt that they used American markings.

The original 1944 Signal Corps caption for the photo being discussed says: “The sky is filled with U.S. Army paratroopers landing at Grave, Holland. The abandoned gliders were used for earlier landings of troops…” Some original Signal Corps captions are incorrect.

Very good article learned new facts about the fighting in Holland

Very good article learned new facts about the fighting in Holland

This was the Polish drop on September 23rd at DZ “O” at Overasselt. The scheduled Polish drop was on September 19, but weather delayed the drop for two days, and as the situation had changed, the Polish drop zone was now outside the village of Driel. The lift was provided by 114 aircraft from the 314th and 315th Troop Carrier Groups. Low cloud ceiling and a botched recall order caused confusion, and 42 aircraft returned to their bases in the UK.

On September 23, the 42 sticks which had returned were flown to DZ “O” by the 31th Troop Carrier Group, where they were dropped BETWEEN glider serials carrying the 82nd Airborne’s 325th Glider Infantry Regiment whose lifts had also been delayed for several days due to the lousy weather – this is the event happening in the article’s very striking still photo. It should be noted that motion picture film exists of this drop.

In the photo captioned “ Brigadier General James Gavin, commander of the 82nd Airborne Division, confers with General Miles Dempsey, commander of the British Second Army, several days into the Market Garden operation.” Gavin was promoted to Major General in October after market garden was started in this article it indicated that he was promoted to his rank before Market Garden but wore a helmet with one a brigadier.general one star according to the article.

In addition to this error, Ridgeway was a Major General throughout WW2. He was not promoted when he become commander of XVIII airborne corp. To my knowledge ALL of the US corps commanders in the ETO were major generals. Lt. Generals headed armies like Patton, 3rd army; Simpson 9th army and Hodge, 1st army. When I read an article and see the author doesn’t even get the ranks correct I really wonder about the accuracy of the rest of the article

Montgomery was egotistical, self centered, and wanted all gory for himself. Ike gave in too quickly for this ill conceived plan that cost far too may lives and injuries. The allied troops did all that was possible in their efforts to seize the bridges assigned.

‘Egotistical, self-centred and wanted all glory for himself.’ That pretty much sums Monty up, although he was also a very capable general who cared much for his troops and who was very popular with his men. The thing is, as well, that ‘Egotistical, self-centred and wanted all glory for himself’ sums up many generals (including several Americans) – you don’t generally get to such exalted rank without those ‘qualities’!

I really worry about the accuracy of an article when they start out giving promotions and ranks that are wrong.

Ridgeway was a maj general at the time of the battle of the bulge. I don’t know when he became a lt general.

Gavin became the commander of the 82nd airborn after Normandy and jumped as the divison commander as a brig general in Market Garden. As he stated in his book he was promoted to Maj General in Oct 1945. These are just the errors that are obvious to me.

I’m afraid there are a number of misrepresentations here. Baffling how British Grenadier Guards are barely mentioned in the taking of the 2 Nijmegen Bridges. Infact, the Germans considered that the 82nd were happy to wait for the British to arrive to mount any serious attack. After all only 200 US troops had tried to take it on the 17th or 18th, from the 8,000 landed. It was the infantry of the Grenadier Guards who bayonet-charged the critical Valkhof and who got onto the main highway bridge, with 505th PIR on their flanks, and supported by British tanks. That was where the Battle of Nijmegen was truly won, at the town end. Tanks rolled across and took the roadbridge under heavy German fire. It had not been taken nor barely secured at the northern end, and they only encountered Americans half a mile towards the railbridge. The 504th PIR were certainly heroic but they played a key role in taking the railbridge, but the road-bridge was a joint venture, and arguably the British played the key role. Grenadier’s were also prominent at the Railway Bridge but again no mention. The Grenadier’s lost 100 dead in this battle. The British Coldstream Guards were transferred from30 Corps to Gavin’s 82nd for 2-3 days and were immediately sent to help 82nd and they retook Mook after the Americans had been driven out. Still no mention!

The 82nd and 101st Division were undoubtedly elite troops, but the delay to take the highway bridge dealt the operation the deathknell. ‘Strike at the bridges with thunderclap surprise’ said American Lieutenant-General Lewis Brereton, overall commander of the 1st Allied Airborne Army. Who to blame? Browning and Gavin. Both were culpable.

Pretty much summed up my thoughts. I was staggered that this article (like the film), suggests that the 82nd AB took the road bridge. They didn’t. A troop of Grenadier Guards tanks, led by Captain Lord Carrington (future Conservative Party politician, Defence Secretary and NATO Secretary General), captured the road bridge. Of course, that’s not shown in A Bridge Too Far, either, because that didn’t fit the narrative. That was a narrative which suggests that the British then stopped for tea, rather than pushing onto Arnhem (at night, without infantry support or intelligence on what faced them – an idea which even the US History of the battle considered would have been foolish.) For a supposedly serious history publication (American, or otherwise), to get that wrong is a pretty egregious error.

The film version also lays part of the blame on the failure of reinforcing units to move forward where most needed. This was depicted as due to the narrow roadways which had not been taken into consideration during the planning process and thus hindered traffic. While there can be no certain way of determining the implication of this problem to the operation’s failure, it does contribute to the image of Montgomery overlooking planning details in an effort to maintain maximum forward movement. Problem was, with this plan, one section failure had a cascading effect. In this instance Patton may have been correct in his original assessment that ignoring his usual methods of rapid movement in favor of Montgomery’s complex plan was the wrong move to make by Eisenhower.

I can’t help but wonder if Eisenhower sided with Montgomery because Ike was still very upset with Patton over slapping two soldiers suffering from battle fatigue in Sicily. When the incident occurred, a furious Eisenhower was seriously considering sending Patton back to the States. Marshall interceded on Patton’s behalf and convinced Ike that he and the Allies needed Patton in command of an army. Nevertheless, Montgomery was given the go ahead for his plan instead of allowing Patton and his 3rd Army to continue their fast-paced advance through eastern France and into Germany.

Montgomery was undoubtedly egoistical and I totally understand why the Americans view him with disdain. But his plan was executed by others, and the RAF wanted 2 drops in a day, Brereton would not go along with this. They strongly considered that a 2nd drop using fixed wing aircraft without gliders could have dropped a good number of additional troops that day.

Montgomery new that the bridges across several key rivers must be secured intact, this is why he proposed coup-de-mains as he acknowledged that it would be very difficult for conventional ground forces to take them intact. So he was trying to actually eliminate risk by grabbing the bridges quickly. Maybe Jim Gavin was overtasked, but neglecting the key objective was inexcusable, and it profoundly affected the outcome. Browning was also culpable, but Gavin confirms it was his personal decision.

30 Corps are often hammered, but they arrived at Nijmegen in 42 hours from starting, just under 2 days and then just 9 miles from the British 1st Airborne at Arnhem. They were privately dismayed that the 82nd, who are a fine division, hadn’t really made serious attempts to take Nijmegen Bridge. The battle of Nijmegen that then took place over 19th-20th September was a superb example of joint-operations. But by then it was arguably already too late due to the delay.

Rather shocking nonsense from the author. You do realise that Monty did not plan Market Garden. He planned Operation Comet, on which he canceled on the 10th of September when fresh intel came in. It was to be a British and Polish operation. Ike passed the concept to Lewis H. Brereton and it became and FAAA operation. The 82nd and the 101st were added to the op. It sounds like the Mr Morgan has got his research from Hollywood or from Ryan’s book – it is the same mistake so many ‘historians’ make. If you doubt me, the please give us all credible source information that says it was Monty’s plan. I won’t hold my breath as you will not find any.

XXX Corp were at Nijmegen Bridge hours ahead of the schedule, and had to do Gavin’s job for him as he failed to follow orders. It was his failure that lead to the failure of XXX Corp to get to Arnhem. The authors and those comments above need to stop spread misinformation, it is disrespectful to those who paid the ultimate price. And it is important we pass down the CORRECT history to the next generation – not some Hollywood nonsense.