By William Stroock

By the beginning of February 1945, the British 14th Army was on the banks of the Irrawaddy River and poised to strike into central Burma. The officers and men of the 14th Army were tired but triumphant. The year before they had fought an epic battle against the Japanese on the plain of Imphal, stopping a Japanese drive on Imphal proper and slugging it out with Japanese forces trying to outflank them to the north at Kohima.

Farther east, British forces, commanded by the bizarre and eccentric Brigadier Orde Wingate, had flown behind Japanese lines in conjunction with Joseph Stilwell’s Sino-American force and cleared Japanese troops out of northern Burma. In late 1944 and early 1945 the British pushed the Japanese away from Imphal, southeast across the Schewbo Plain. Now the Japanese Army, badly battered and demoralized, waited on the banks of the Irrawaddy for the 14th Army’s next offensive.

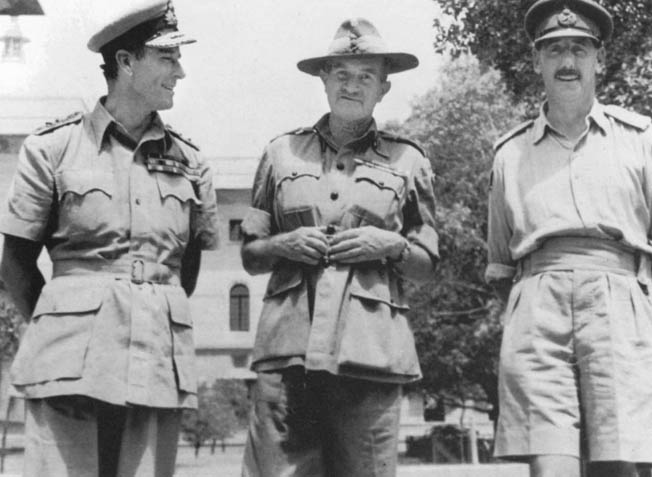

William Slim and the 14th Army

The architect of 14th Army’s victory was General William Slim. Because of his success in the Middle East and his knowledge of the British Indian Army, he was asked by the British Commander in Chief in India, Sir Archibald Wavell, to take command of British forces there. Slim arrived in early 1942 and presided over the British defeat in Burma. Under Slim’s command, BurCorps, as the British Army in Burma was called, fought doggedly but was outnumbered and unprepared for the tenacity of Japanese forces and their infiltration tactics. Time and again outflanked, British commanders in the field kept pulling back, only to be outflanked again at the next action.

That Slim was able to extricate his forces from Burma at all is testament to his skills as an organizer and commander. Unlike his more aristocratic counterparts in the Army, Slim had come from a humble background and had risen through the ranks. He had served many years in India and commanded a British Indian Army division during the Iraq campaign of 1941 and later in Vichy Syria and in Persia. After the war he wrote an outstanding memoir of the Burma campaign, Defeat into Victory. In his book, Slim comes across as serious and professional, but also affable and kind.

In the hills of eastern India, Slim remade the 14th Army, turning it into a force capable of beating the Japanese. He started a vigorous training program that eschewed static lines and instead emphasized small bases protected by aggressive patrols. Slim drove home to his commanders the idea that they were not to withdraw when Japanese units got around and behind them. Instead they were to hunker down and call in reinforcements, for in Slim’s mind it was the infiltrating Japanese who were then surrounded. Slim also saw the potential of aerial resupply, which was realized during Orde Wingate’s foray into northern Burma in which five British brigades were resupplied through the air. Slim made aerial resupply an integral part of his central Burma campaign.

Slim’s 14th Army was a polyglot affair, a mixture of troops from across the British Empire. A British Indian Army division comprised three infantry brigades, each of three battalions; two of these battalions were Indian––mixed Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, or Gurkha––while the third was from Britain.

Three divisions, the 11th, 81st, and 82nd, were from Africa. By 1945, the 14th Army had become highly specialized with tankers, sappers, airborne troops, long-range penetration brigades, and a host of other military job descriptions.

The new 14th Army, forged into a potent weapon in the jungles and hills around Imphal, had spent late 1944 and early 1945 chasing the Japanese across central Burma to the mighty Irrawaddy River. In truth, Slim had hoped that the new Japanese commander of the Burma Area Army, General Heitaro Kimura, would mount a typically fanatical defense of the Schewbo Plain, allowing 14th Army to surround and annihilate Japanese forces there.

Seeing what had happened to the Japanese 15th Army around Imphal, where it had attacked and fought beyond all hope of victory, Kimura decided to fight a delaying action on the Schewbo Plain and instead gathered his strength on the Irrawaddy. He would fight for the west bank but believed the primary battle should take place along the east bank of the river. Kimura’s tactics were unusual for a Japanese commander, but they were sound.

As for Slim, an all-out Japanese defense on the Schewbo Plain would enable British mechanized units to envelope enemy forces, who would be pinned in the open and bombarded from the air.

Battered and Beaten: The Japanese

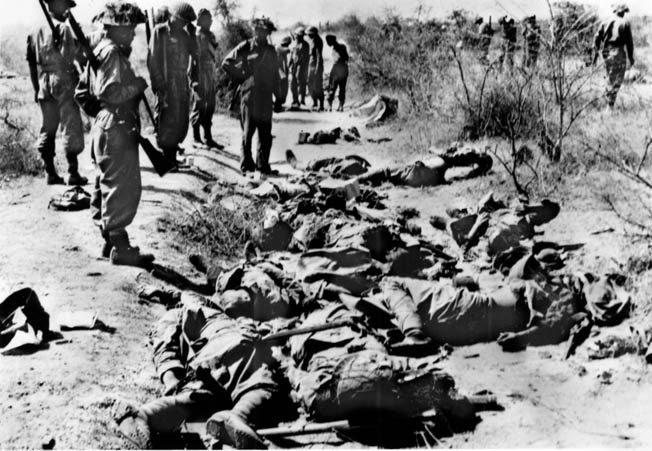

Besides, at Imphal, the Japanese 15th Army had lost its edge. The 15th, 31st, and 33rd Divisions, at the very end of a long line of supply, had been impaled against British defenders who were dug in, could count on regular air support and aerial re-supply, and were commanded by General Slim, who absolutely refused to consider the possibility of defeat in the battle for Imphal.

These Japanese divisions were now at about half strength, with the remaining troops wracked by malnutrition and dysentery. Morale was low. Three other divisions—the 2nd, 49th, and 53rd—were also on hand. Reinforcements might be found among the Japanese 33rd Army to the north, then battling the Americans and Chinese, and the Japanese 28th Army at Arakan in the south. There were also scattered units of Subhas Chandra Bose’s Indian National Army fighting on the Japanese side.

The key to Kimura’s position was Meiktila, about 50 miles south of Mandalay. The town was a road and rail hub through which Japanese supplies to the north must flow. Without Meiktila, Kimura’s position in Mandalay and central Burma was untenable.

Slim understood that Kimura and the Japanese 15th Army would have no choice but to mount a fanatical defense on the Irrawaddy line, and he was happy to fight them there––only he did not intend to simply batter his way through Japanese defenses. Slim’s plan, Operation Capital, concentrated on Meiktila.

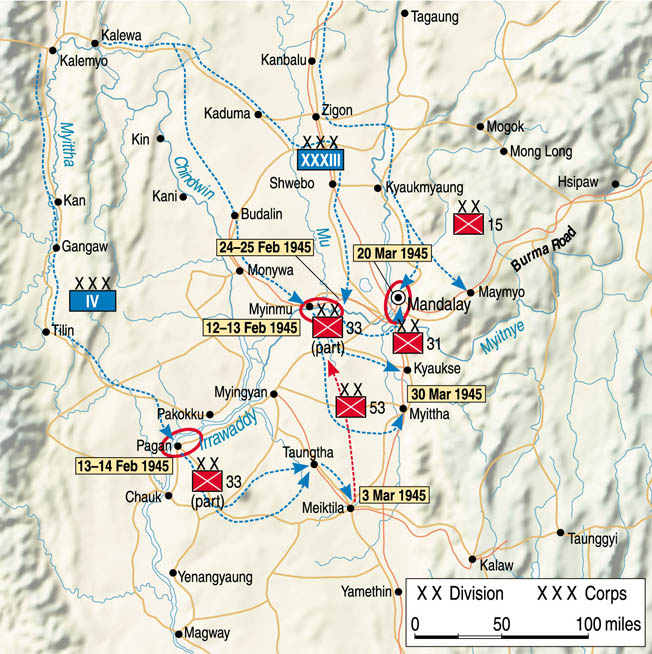

In the north, 33 Corps would drive down the east bank of the Irrawaddy to Mandalay and pin Japanese forces in the central Irrawaddy River area. This was just a feint. The real thrust—the “vital thrust,” as Slim called it—would occur south at Pakokku. Here, 4 Corps would cross the Irrawaddy and then dash 50 miles east to Meiktila. They would be tethered to the rest of 14th Army via aerial resupply, and therefore capturing a pair of airfields northeast of Meiktila was a key objective.

Wrote Slim, “If we took Meiktila while Kimura was deeply engaged along the Irrawaddy about Mandalay, he would be compelled to detach large forces to clear his vital communications.” Thus, Slim hoped the Japanese would once more impale themselves on British defenses, this time in the jungle around Meiktila.

The able General Frank Meservey commanded 4 Corps. Meservey had seen extensive action in Africa, Ethiopia, Libya, and Egypt before being sent to India in 1942. He commanded the 7th British Division during the failed Arakan offensive of 1943 and during the battle of the Admin Box, where he was surprised and badly mauled but held on tenaciously until Japanese forces withdrew. For Slim, he was the only man to command the dash to Meiktila. He wrote that Meservey “had the temperament, sanguine, inspiring, and not too calculating odds that I thought would be required for the tasks I designed for 4 Corps.”

The corps comprised Meservey’s 7th British Division, the Leshai Brigade, the 14th East Africa Brigade, the 255th Armoured Brigade, and the 17th Indian Division. The 17th Indian Division was commanded by General David “Punch” Cowan. To him fell the task of taking Meiktila (the 255th Armoured Brigade would swing north and then east to the airstrips) and then holding the town against the expected determined Japanese counterattacks.

Across the Irrawaddy

The first step was to get across the river. The British 7th Division would open Operation Capital by crossing the Irrawaddy and establishing a bridgehead on the east bank. The 33rd Indian Brigade would be the first across while to the north and south the 28th East African and 114th Brigades would make noise and otherwise distract the Japanese. Prior to the actual attack, the brigades trained for a night crossing. An impressive flotilla of 120 boats and 18 rafts was assembled. These would ferry the 33rd Brigade across one battalion at a time.

The operation began in the early morning hours of February 14. Even though the crossing ran into myriad problems—units becoming lost in the dark, boats drifting downstream, and heavy fire once the Japanese and Indian National Army troops realized they were under attack, most of the brigade was ferried to the east bank of the Irrawaddy by the end of the day; the nearby village of Nyaungu was in British hands.

Japanese forces around Nyaungu and to the north and south pulled back, leaving the eastern bank of the river to the British. Meservey ordered the 17th Indian Division and 255th Armoured Brigade to be brought across. It took a week to bring these forces to the east bank and to accumulate supplies.

But Meservey and 4 Corps had time because the Japanese seemed paralyzed. As the operation unfolded before them, there was considerable disagreement among the Japanese high command as to British intentions. It was not until 4 Corps took Thabutkon and pushed east that Kimura determined the British were mounting a major effort against Meiktila.

The city and its environs were commanded by General Tomekechi Kasuya. He had more than 12,000 men under him, but these were mostly rear echelon troops and independent defense battalions. However, as the crisis worsened, Kimura rushed reinforcements to the area, including two line infantry battalions, an artillery regiment, and an antitank company. Contrary to British expectations, Meiktila would be well defended.

The Vital Thrust to Meiktila

By the time Kimura figured out what Slim’s intentions were, 4 Corps was ready to advance. Before them was open country and an old British imperial road suitable for large mechanized columns.

Slim’s plan called for an advance in stages. The 4 Corps advance was directed about 20 miles east to Taungtha. From there the units could pivot northeast toward Mandalay, 35 miles away, or southeast to Meiktila itself, 20 miles distant. The advance would be under the direction of General David Cowan, as his 17th Indian Division would be in the lead.

The drive to Meiktila began on February 21. Until this point the campaign had gone smoothly, but now 4 Corps and 14th Army were threatened when Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek demanded the return of all Chinese forces in Burma, including supporting transport aircraft. Those aircraft were vital to Slim’s aerial resupply. “The loss of the aircraft would have been fatal to my operations,” he wrote.

Admiral Louis Mountbatten, the Supreme Allied Commander in South East Asia, personally intervened, both with Chiang and with U.S. Army Chief of Staff General George Marshall, and while they could not stop the withdrawal of Chinese forces, a move that would free up Japanese troops to come south, the American transport aircraft were saved from Chiang.

The first phase of the advance went well. The Japanese were in full retreat and could not possibly stand against a British mechanized attack through open country, though they did leave behind the usual booby traps, snipers, and suicide squads. The 4 Corps troops advanced on a two-brigade front with the 48th Brigade in the north and 255th Armoured Brigade in the south. They took Hinawdwin on February 23 and Taungtha on the 24th. General Cowan left the 48th Brigade at Taungtha, where it was resupplied by air. The 4 Corps spearhead raced south and the 48th Brigade now brought up the rear as the 99th Brigade was flown into Taungtha.

On February 27, they encountered a Japanese position at Ledaingzin, but Cowan ordered the 63rd Brigade to hook north around it. On the 28th they were five miles from Meiktila.

Meiktila is wedged between a pair of man-made lakes, one in the north and one in the south, so any assault on the town would have to be launched on an east-west access. As such, Cowan split his force in three. The 48th Brigade remained on the main road to Meiktila. At the same time, the 63rd Brigade split south about four miles across the eastern rail spur to the road leading southwest out of Meiktila. Meanwhile, the 255th Armoured Brigade executed a long left hook around Meiktila and the northern lake, nearly 10 miles in all, cut the north and northeastern roads out of town, and established itself on the eastern edge of the town on March 1.

The assault on Meiktila began that day, with the 48th Brigade pressing Japanese defenses in the west. But this was just to hold them in place. The main action took place in the east where the 255th Armoured Brigade fought its way into town. The Japanese contested every block. Slim noted that there was heavy machine-gun and antitank fire. The advance was slow, and pockets of Japanese were left behind the line of advancing tanks.

As night fell, Cowan chose to pull his tanks out of Meiktila, leaving behind only strong infantry patrols, for fear Japanese suicide bombers would come out of the rubble and assault the tanks. Though it meant they would have to fight over much of the same ground in the morning, Slim supported the decision.

The next day, Slim actually flew into Meiktila in an American general’s plane (the RAF, citing safety concerns, had refused to fly him), from which he observed the battle. Once more the fighting was house to house, usually featuring a squad clearing a house with support from a Sherman tank. Slim took a few pages of his memoir to describe one such operation by a platoon of Gurkhas, concluding, “It was all very businesslike.” On March 2, the 48th Brigade pushed into Meiktila proper from the west. The added pressure was too much for the Japanese and drove them to the shores of the south lake. Slim wrote, “Meiktila was a shambles, and by six o’clock on the evening of the 3rd, it was ours.”

The Spear at Meiktila

Now it was time for Cowan and 4 Corps to hunker down for the inevitable Japanese counterattack. On an operational level Cowan played defense, but tactically 4 Corps went on the offensive. Cowan eschewed static defenses in favor of Slim’s doctrine of loosely held lines and aggressive patrols. His troops, in the words of Slim, “struck out in all directions. Infantry and tanks went out daily to hunt, ambush and attack approaching Japanese columns … in a radius of twenty miles of the town.”

British troops were greatly aided by Allied airpower, which had almost complete control of the sky. Control of the air was absolutely vital, as 4 Corps was tethered to the 14th Army by aerial resupply alone, through the airstrip northeast of town.

General Kimura was well aware of Cowan’s dependence on aerial resupply. He could never hope to overpower fully supplied British forces, not with the bedraggled state of his army. As such, Kimura made the airstrip the focal point of his counterattack. On paper Kimura had powerful forces at his disposal. The elite Japanese 18th Division, which had spent the last year battling Stilwell’s Sino-American force, was rushed south, save for one battalion. A regiment each from the Japanese 2nd, 33rd, and 53rd Divisions was also commandeered for the counterattack.

These were supported by the remnants of various artillery and support units, including a tank regiment. Spare infantry battalions would also be gotten from other divisions as the battle unfolded. Kimura did not direct the operation himself but instead placed General Tadakatsu Honda in command.

Honda deployed the Japanese 18th Division north of Meiktila to defend supply lines to Mandalay. With the Japanese 49th Division he planned to attack the lines of communication among British forces in Meiktila. The 49th Division would attack the Irrawaddy bridgehead and attempt to destroy it, though given the severe beating the division had taken over the last few months, it was unlikely it could overrun the bridgehead. Meanwhile, the various battalions and regiments to the east would attack Meiktila.

Over the course of the next few weeks, the Japanese 49th Division’s efforts against the Irrawaddy bridgehead, defended by the 28th East African Brigade, never amounted to more than a nuisance. The division simply lacked the strength to dislodge the Africans, though it did constantly harass their positions.

At the same time, Japanese forces attacked Meiktila. There was no dramatic beginning of the battle, just a gradual building of pressure. British defenses were strong and flexible. Cowan’s 99th Brigade occupied the town proper. At each of the six roads leading out of Meiktila was an infantry company. Behind these were mobile forces that would push out and engage Japanese troops as they converged on the town.

The first Japanese effort came from elements of the 49th Division, which pushed against the south-southwest sector of Cowan’s lines. The attack was disrupted by British columns, which swept out of Meiktila and engaged Japanese forces on March 5. Other spoiling attacks followed. One such column was composed of two infantry companies, a troop of armored cars, an antitank battery, and an artillery battery. Launched on March 8, this column drove south to Pyabwe and cleared several villages of Japanese forces before returning to the Meiktila perimeter on the 10th.

The next week, most of the 63rd Brigade, responsible for the northern approaches, attacked up the road to Mandalay in an effort to locate Japanese artillery batteries that had been shelling the airfield. Several guns were located and destroyed, and more than 300 Japanese troops were killed.

The Japanese efforts around Meiktila were a bust, hampered by exhausted units and aggressive British tactics. Further hampering the attacks was British intelligence. In his memoirs, Slim related how British radio intercept units had busily triangulated the location of Japanese tactical and operational headquarters. “With the help of air reconnaissance and informers, we were even able to pinpoint some of the more important headquarters,” he wrote.

Japanese headquarters were subject to artillery and aerial attack, and in some cases, attack by flying mechanized columns. “We followed them when they moved, and bombed and harried them when they halted,” said Slim. The net effect of these operations was to disrupt Japanese communications and prevent orders being issued by commanders, many of whom were too busy simply trying to stay alive to make decisions.

Beginning on March 15, elements of the Japanese 31st Division hit the eastern airfield. The first effort was launched by a single battalion, which advanced to the jungle edge and brought the airfield under fire. For the next three nights the Japanese attacked British positions without success, though they did destroy one plane and some fuel tanks.

The last attack was pushed away from the British perimeter by a furious counterattack, which destroyed the Japanese battalion as an effective fighting force. Over the course of these three days, British and American transports were flying in reinforcements under fire, in this case the 9th Brigade, which on March 18 took over the defense of the airfield.

Two more Japanese battalions joined the attack and kept the airfield under constant fire. Japanese artillery was especially effective, accurate, and well concealed. Spotting Japanese guns, in the words of an artillery spotter named Jack Scollen and quoted by the historian Louis Allen, “required vast amounts of patience and not a little luck because their guns were almost always dug deep down under cover where they could not be seen from the air and even their flashes were difficult to spot.”

The guns were also effective against British tanks, several of which were inevitably knocked out with each British counterattack. Another danger to British tanks was Japanese mines—in this case, human mines—suicide soldiers who would hide in a ditch with an artillery shell and a rock and wait for a tank to drive overhead.

Thus the battle for the airfield was fought, with Japanese artillery barrages rolling across the field followed by Japanese attacks, some of which actually managed to occupy the runway for a time, followed by British counterattacks, which inevitably drove the Japanese back into the jungle. The constant fighting for the airstrip rendered it inoperable for a few days, and until it was repaired the 17th Indian Division was reliant on airdrops for its supplies.

However, the combination of British infantry, armor, and air power proved irresistible and gradually pushed the Japanese 18th Division away from the airstrip. By March 29, the Japanese, with more than 2,500 dead on and around the airstrip, realized they had lost the battle and pulled back.

While the battle for Meiktila was being won, General Meservey detailed the British 7th Division to open up a land bridge to Meiktila. This entailed the clearing of hills just off the bridgehead and the capture of Taungtha to the east.

The town fell without too much trouble, but it took the British 7th Division a week to clear the Japanese out of the hills to the north and east. To do so required taking the town of Myingyang. The division was on the outskirts of the town by March 18, but as with all Japanese units, in this case elements of the Japanese 15th Division, forces in Myingyang mounted a fanatical defense. The British 7th Division needed four days of close quarters, house to house fighting to secure the town.

To support Myingyang, Honda sent scattered Japanese and Indian National Army units against the 7th Division’s bridgehead at Chaulk, but these attacks were easily beaten back. With the Japanese cleared out of Myingyang, their counterattack at Chaulk halted, and with the town of Taungtha in British hands it was only a matter of time until Meservey opened up a land route to Meiktila.

Said Slim, “By the last week in March, the Battle of Meiktila had been won. It had been intended as the decisive stroke and I had subordinated everything to its success, yet it had been only half of the great Battle of Central Burma. That other half had been fought out simultaneously around Mandalay.”

The Liberation of Mandalay

While the battle for Meiktila was being developed and fought, 33 Corps was crossing the Irrawaddy and preparing for a drive on Mandalay. The British 19th Division was 40 miles to the north, with the town of Madaya lying between it and Mandalay. The river turned west below Mandalay, and 20 miles away was the British 2nd Division. A further 20 miles west was the British 20th Division, which would cross the Irrawaddy and fight east to Kyasuke.

With Meiktila engaged and Mandalay about to be attacked, Slim felt the decisive part of the Irrawaddy campaign had arrived. “It was not Mandalay or Meiktila that we were after but the Japanese army,” he wrote. The British 19th Division was commanded by Thomas Winford Rees, an experienced general who had led divisions in Ethiopia and Libya, but in Libya he had been relieved of command after clashing with his corps commander. Fortunately for Slim and the British cause in Burma, Wavell offered him command of the British 19th Division in 1942.

North of Mandalay, the remnants of the Japanese 15th Division, badly mauled in the previous months’ fighting, was unable to slow the British advance. Two British brigades pushed toward Mandalay “like a rush of waters over a broken dam,” according to Slim. They did not slow until March 4 at Madaya, moving to the south bank of the Chaungmagyi River. Even in this defensible position Japanese resistance was easily swept aside, and by March 8, the British 19th Division was outside Mandalay.

By attacking from the north, the British 19th Division faced two tough obstacles. The first was Mandalay Hill, a rise just outside the city topped by Buddhist temples and laced with catacombs. Elements of the 98th Brigade attacked the hill on March 9 and pushed their way up the steep slope. As usual the Japanese contested every inch, and the Gurkhas leading the assault had to clear them out with bayonets. Even after the hill was cleared, the Japanese in the tunnels below held out. British troops above mercilessly rolled gas barrels into the catacombs and set them afire.

The second obstacle was Fort Dufferin, a Buddhist temple with high, medieval-style walls and a moat. Within the fort were a large park and the palace of the last Burmese king. The British refused to bomb the fort because of its religious significance, though strafing runs were permitted, and British troops fought their way inside Mandalay and surrounded Fort Dufferin. They then set about the task of breaching the walls. Slim compared the effort to a battle in the Sepoy Mutiny.

Throughout March 18 and 19 British troops mounted forays across the moat, including a clandestine night attack in which Gurkhas tried to scale the walls, but these efforts were all repulsed. After conventional bombing attempts on the wall failed, British and American flyers then tried skip-bombing the wall, bouncing bombs off the moat and smashing them into the bricks. This opened only a small breach, and it would have been suicidal for British troops to force their way through. “I was prepared to wait,” said Slim. The Japanese, however, weren’t, and on the night of March 19-20, they withdrew from the fort.

The Liberation of Rangoon

Meiktila, Mandalay, and central Burma were British once more, but Slim had one more goal: Rangoon, nearly 300 miles to the south. Between Slim and his ultimate target were the Japanese 28th and 33rd Armies. The shattered remains of the Japanese 15th Army plus the 56th Division were held in reserve. The units of the Japanese 28th and 15th Armies were depleted and lacked transport and guns, but they could still fight. General Honda would once again command the Japanese defense.

Also confronting Slim and the British 14th Army was the monsoon, seven or eight weeks away. Once this arrived, central and southern Burma would turn to mush, and a drive on Rangoon would be impossible. In his orders for the Rangoon operation, Slim wrote that his goal was “the capture of Rangoon at all costs and as soon as possible before the Monsoon.”

Operation Extended Capital, as it was called, fell to Meservey and 4 Corps. It was closest to Rangoon, and the 255th Armoured Brigade would be an important weapon in the push south. In conjunction with 4 Corps, elements of British 15 Corps would make a landing just west of Rangoon at Elephant Point in an attempt to take the city before the Japanese could entrench themselves there. The amphibious assault, called Operation Dracula, was planned for early May.

With the 20th Indian Division in the north and the British 7th Division in the south clearing out pockets of Japanese resistance along the Irrawaddy, 4 Corps made ready. The success of the drive would hinge on the ability of the British to move fast and keep their units supplied. There would be stiff fighting for a trio of towns from north to south, Pyabwe, Toungoo, which was the scene of heavy fighting in 1942, and Pegu. In many ways it was a race to see who could take Rangoon first, 4 Corps or 15 Corps. Slim described the Dracula project as “a hammering on the back door while I burst in at the front.”

The drive began on March 30, with the 17th Indian Division and the 255th Armoured Brigade pushing south on a two-brigade front against three Japanese divisions around the town of Pyabwe. Each of the many small villages around Pyabwe was occupied by the Japanese and had to be cleared house by house. There was a particularly vicious battle for the village of Yindow, where the Japanese had concrete bunkers and antitank guns. For three days the British tried to clear it.

Finally, Slim ordered the 99th and 63rd Brigades to bypass Yindow and push south, leaving the village to the British 5th Division, which finished the job. On April 10, the 17th Indian Division was just outside Pyabwe. Meservey sent the 255th Armoured Brigade around the flank, and it entered Pyabwe from the south. By the 11th, the town was in British hands. In the course of the fighting, three Japanese divisions, the elite 18th, 49th, and 53rd, were annihilated. The entire Japanese 28th Army was destroyed.

The door had been kicked in, and the way to Rangoon lay open. “They were off!” Slim joyously wrote. The advance was taken up by the British 5th Division, which gobbled up ground a dozen miles at a time. Realizing that Honda could not possibly hold, Kimura gathered troops from all over Burma and thrust them in front of the advancing British. Japanese reinforcements were harried and ambushed the entire way by Karen guerrillas, who themselves loathed the Japanese and were assisted by British and American advisers. These reinforcements were not able to stem the tide of the advance. Some units tried to sever British supply lines, but these efforts were easily stopped by Rees and 33 Corps, which was holding the line east of Meiktila.

The British had plenty of transport, tanks, and air support and were in flat, open country. On April 22, the 5th Division fought its way into the town of Toungoo, where Honda kept his headquarters. The British captured the headquarters, but Honda escaped, though he was incommunicado for several days. British forces were now a mere 160 miles from Rangoon. The next day, the 5th Division advanced a staggering 30 miles south to Pyu, where it accepted the surrender of the 1st Division of Bose’s traitorous Indian National Army. Slim put the prisoners to work repairing the local airfields, where supplies would now be flown in to support the advance.

From there, the 17th Indian Division assumed the lead. In the next two days it advanced 20 and then 15 miles, easily sweeping aside all resistance. By then 4 Corps was encountering abandoned Japanese equipment, vehicles, and even Allied POWs. The only strongpoint left was the town of Pegu, straddling both banks of the Pegu River and heavily fortified by the Japanese, just 47 miles north of Rangoon. Cowan attacked the east bank of the town first and then sent a brigade to circle around the flank and enter the west bank of the town. It was tough going, and Slim described the resistance as “bitter.” But after two days, by April 30, the British had control of the town.

Then the monsoon hit nearly a month before it was due. The torrential downpour turned the road south to Rangoon into a mud bog and waterlogged the countryside. Advancing was now all but impossible. What the Japanese could not do, it seemed Mother Nature had. However, on May 2, 1945, the Royal Navy executed Operation Dracula and landed elements of the 26th Indian Division at Elephant Point, west of Rangoon. Through the rain British troops advanced toward Rangoon and entered the city the next day. The Japanese had pulled out. Slim described the scene: “The population in thousands welcomed our men with a relief and joy they made no attempt to restrain.”

Hard battles remained to be fought as the remnants of three Japanese armies were caught between liberated Mandalay and Rangoon, but Japanese power in Burma was forever broken. The mild-mannered and humble William Slim had remade a defeated army into the best-trained, most professional force in the British Empire. By the end of the Burma campaign the officers and men of the British 14th Army—British, Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, Gurkha, African—were experts in jungle warfare capable of active defense and aggressive offense. They were specialists in deep penetration and close air support who could use combined arms to overwhelm fanatical Japanese defenders.

By the end of the war, the 14th was the best army in the British Empire.

As a RAF Radar Mechanic I was drafted into Meiktila for a few days to repair their Eureka set. I had. I idea of the danger I was in !