By Jeff Patton

Following the spectacular success of the Allied air campaign against Iraq during Operation Desert Storm in 1991 and against the Serb forces in Kosovo in 1999, the value and efficiency of utilizing air power to shape or forgo the need for a ground battle has been taken for granted by military planners. It was not always this way.

The successful application of current air power to shape the battlefield had its rocky genesis in the air campaign supporting the Allied advance up the boot of Italy in World War II—a campaign codenamed Operation Strangle.

Air interdiction in Italy did not start with Operation Strangle. Allied air interdiction of German supply lines had begun before the September 1943 Allied landings in southern Italy. However, Operation Strangle was unique in that it departed from prior practice by attempting to create a near total stoppage of German supplies far from the battlefront.

The German’s Crisis in Italy

Following the fall of Sicily to the Allies in August 1943, the Germans were able to evacuate more than 60,000 men and their equipment to the mainland of southern Italy. But Hitler was convinced that his Italian cohort might be close to committing an “act of treachery” by signing a separate armistice with the Allies.

With the arrest and imprisonment of dictator Benito Mussolini by the Italian government in July 1943, the OKW (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, the German high command) began moving troops into northern Italy in anticipation of being forced to occupy and defend the entire peninsula without the aid of the Italian armed forces.

The commander of German forces in southern Italy, Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, reorganized these forces into the Tenth Army. This army consisted of the XIV Panzer Corps with three divisions and LXXVI Panzer Corps with two divisions and elements of a third; two additional divisions were in reserve near Rome. All were seasoned troops. Some were veterans of the fighting near Stalingrad who had escaped annihilation and had been reconstituted into new units in France. Others were veterans of the Eastern Front and the fighting in North Africa and Sicily.

The invasion of mainland Italy and the collapse of Italian forces caused a crisis in German strategy. The two field marshals in Italy—Erwin Rommel with Army Group B in the north and Kesselring with Tenth Army in the south—were diametrically opposed as to the best strategy to counter the Allies.

Rommel argued for a retreat of all German troops north of the Po River. He would concentrate his forces to defend against an Allied advance through Austria or to counter an Allied swing through Yugoslavia into Austria and southern Germany.

Kesselring countered with the proposal to defend all of Italy. He was convinced he could stall the Allied advance by utilizing the mountainous terrain of Italy and lack of an adequate road network to keep not only the Allied armies at bay but also deny airfields to them that they could use to stage bombing missions closer to the German homeland. Hitler did not want to yield a single foot of ground. His refusal to allow his commanders to use a tactical withdrawal had already cost the Wehrmacht the Sixth Army at Stalingrad and the Afrika Korps. In the end, Hitler sided with Kesselring and moved Rommel and Army Group B to France to prepare for a possible Allied invasion. Given Hitler’s blessing, Kesselring went to work.

Operation Strangle: Paving the Way For Diadem

By November 1943, the Allied advance northward in Italy had been stalemated by experienced, well dug in German forces. Facing the Allies was Germany’s greatest defensive genius. Kesselring had chosen a line that ran east-west across the Italian peninsula approximately 70 miles south of Rome from the mouth of the Garigliano River across the Apennine Mountains to the mouth of the Sangro River on the Adriatic Sea.

The line had a narrow coastal plain in the east, rugged mountainous terrain in the middle with few roads, and a wider coastal plain in the west consisting of the Liri River Valley that was overlooked by the high terrain of Monte Cassino. The defensive fortifications consisted of several lines for defense in depth and were collectively known as the Winter Line, with the main defensive line codenamed Gustav.

For six months, Kesselring, now sole commander in Italy and head of Army Group C, had swelled his forces to 19 divisions and had stymied the further advance of the British Eighth and American Fifth Armies. To counter this stalemate, the Allies planned a World War I-style “big push” to break the Gustav Line, but this planned Allied spring offensive, codenamed Diadem, required a reduction of the German Army’s combat power to be successful. The tool that promised to do that was air power.

Operation Strangle was one of the few air campaigns in World War II in which it is possible to observe the results of air interdiction alone, unaided by supporting arms, in shaping the battlefield for the success of ground forces. It was a milestone in the development of air force doctrine on air interdiction, and the lessons learned and the effectiveness of the campaign are very much in the eye of the beholder.

Operation Strangle was ordered by the Combined Chiefs of Staff after the abortive attempt to take Monte Cassino in March 1944. Its stated objective was to “reduce the enemy’s flow of supplies to a level which will make it impossible to maintain and operate his forces in central Italy.”

The Questionable Conclusions of Operational Research

The commander of the Mediterranean Allied Air Forces (MAAF), General Ira Eaker, was a proponent of the plan and looked upon Strangle as a showcase for the effectiveness and utility of air power. U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) leaders, too, were eager to showcase the ability of air power to shape the battle on the ground.

A year previously, disjointed penny packet distribution of air assets to individual army ground commanders in North Africa led to inefficiencies and inconclusive results. Aerial bombing showed promise by disrupting the movement of German and Italian troops to the front lines in Sicily. Now, at last, was an opportunity to show how air power alone would force an enemy army to disengage and withdraw due to the destruction of his logistical support. Not only did USAAF leaders have a gut feeling what air power could do, they could empirically prove it.

General Eaker was a believer in the British Air Ministry’s scientific analysis of warfare titled Operational Research. Operational Research was composed of nonmilitary men whose professional expertise was turned to solving wartime problems.

One of the members of the Operational Research team at the Air Ministry was a British medical doctor named Solomon “Solly” Zuckermann. Zuckermann’s specialty was research into primate behavior in the Anatomy Department at Oxford University. Due to his familiarity with primates, he was commissioned to do studies on the effectiveness of the German Blitz on England—how bomb blasts affect monkeys (and humans), the merits of one size or kind of bomb over another, and more.

Zuckermann had risen to prominence by predicting that an aerial bombardment of the Italian island of Pantelleria, south of Sicily, would lead to its surrender. When the Italian garrison commander welcomed the first invasion craft with a white flag, Zuckermann’s stock rose as a genius of Operational Research.

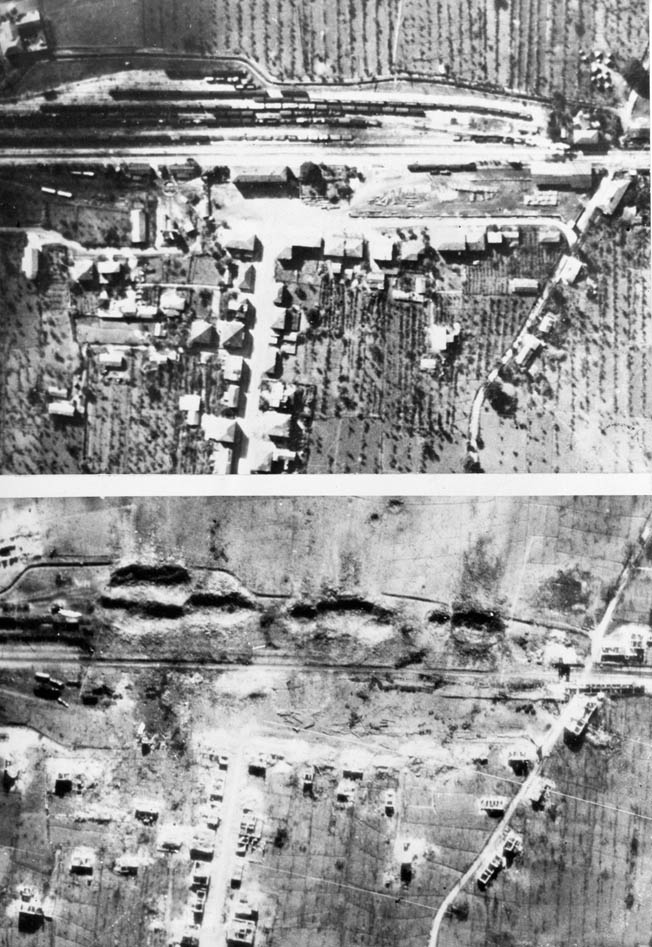

It was Zuckermann’s belief that the enemy’s communications were his Achilles heel. He considered the railroad marshaling yards, bridges, and roads critical targets. Since he believed bridges and roads were notoriously hard to bomb, railroad marshaling yards promised to be key targets that could be easily hit and dramatically affect the enemy’s logistical support.

The large size of marshaling yards ensured there would be less wastage of bombs that fell outside their aiming point. Railroad marshaling yards thus became the primary initial focus of Strangle.

The overall commander of Allied forces in Italy, Field Marshal Harold Alexander, was deeply skeptical of Strangle’s focus on railroad marshaling yards.

“As far as Italy was concerned,” he said, “the fallacy of the policy of attacks on marshaling yards lay in the fact that these are usually on level ground and always contain a large number of parallel tracks so that any damage can be rapidly repaired and a through line established in a very brief time.”

“A reduction in rolling stock and facilities was of little importance as for their military purposes,” he continued, “the Germans only needed about 16 percent of the total available. A broken bridge on the other hand meant a long delay and stores had to be ferried round the break by road thus wasting as much fuel as would be lost from the destruction of a good-sized dump.”

Planners in London, who had experience in planning the strategic Combined Bomber Offensive, thought the best way to accomplish the interdiction mission was by concentrating attacks on railroad marshaling yards. General Ira Eaker’s Mediterranean Allied Air Force (MAAF) planners in Italy pushed for the targeting of bridges and rail lines. This difference in philosophies did not fill Fifth Army Commander General Mark Clark with confidence in its success.

Judging the Effectiveness of Operation Strangle

One of the proponents of Strangle’s effectiveness on the German side was the Commander of Luftwaffe forces in Italy, General Erich Ritter von Pohl. In a postwar debriefing, General Pohl stated, “In the spring of 1944, the German truck transportation system was, for the first time, seriously threatened by systematic commitment of enemy fighter bombers … such that the supply situation at the front was very serious.”

It is a common theme for German officers to emphatically credit Allied air power and air interdiction with a major share of the responsibility for the defeat of Axis forces in Western Europe by denying them freedom of movement. These “claims” could be discounted as self-serving efforts by Wehrmacht officers to excuse the failure of the German Army. General Pohl’s comments on the effectiveness of Allied air interdiction could be influenced by his air force professional leanings, his desire to excuse the defeat of the German Army, or they could be the unvarnished truth.

While Pohl may have anecdotal information to share on the effectiveness of Allied air interdiction, during Strangle he was behind a desk in Rome and not in a position to observe its results firsthand. To get a more accurate viewpoint, it is necessary to look at precisely what effect Strangle had in reducing the flow of supplies to the Wehrmacht.

Intelligence officers in the MAAF estimated that Kesselring’s 19 divisions along the Gustav Line consumed 5,500 tons of supplies, including fuel, per day. They also estimated that the Italian railroad system had, at the start of Strangle, a capacity of 80,000 tons a day. By performing straight-line calculations, they predicted that if interdiction could cause a 93 percent reduction in rail traffic, then the German Army would run out of consumables.

As it turned out, their intelligence was flawed. According to German quartermaster reports, the 19 divisions on the Gustav Line consumed only 2,500 tons of supplies a day when not engaged in combat, and the trickle of vehicle resupply, coupled with coastal barges and horse-drawn transport, supplied an average of 3,000 tons a day.

The result was, by the time of Operation Diadem, the breakthrough of the Gustav Line, the supply dumps for Army Group C had actually increased from 17,000 to 18,000 tons after Strangle began. The commanders of the German Tenth Army and XIV Panzer Corps made no mention of supply shortages even during the heaviest fighting, and Kesselring said his supply situation was satisfactory during the 20 months from the Allied invasion of the Italian mainland to the end of the war.

A Failure of Allied Intelligence

The British pioneered the use of scientific analysis for judging the effectiveness of warfare, and the United States followed their example. The United States had established the Committee on Operational Analysis (COA) composed of scientists, economists, industrial engineers, psychologists, military men, and others who analyzed the enemy’s capabilities both in detail and holistically to determine vulnerabilities.

Additionally, the Air War Plans Division had the responsibility to formulate the operational plans to carry out the targeting suggestions of the committee. Unfortunately, the COA frequently got things wrong. It consistently misinterpreted German economic and military resiliency and advocated the attacks on the German ball bearing factories that cost the USAAF 60 bombers and 600 men on one attack on Schweinfurt with little impact on the German war industry. Likewise, they overemphasized the significance of attacks on railroads, especially the marshaling yards in Italy.

The MAAF had been conducting a low-level interdiction campaign prior to Strangle. When Fifteenth Air Force heavy bombers were prevented from bombing their primary targets north of the Alps, they used railroad marshaling yards in the Po Valley in northern Italy—from Venice westward through Padova, Vicenza, Verona, Brescia, Pavia, Milano, and Torino—as secondary targets. These yards had been bombed sufficiently to cause doubts in the minds of USAAF targeting officers as to the effectiveness of the Zuckerman plan.

In January 1944, three months prior to Strangle, Twelfth Air Force intelligence personnel sent a report to MAAF headquarters stating that marshaling yards were poor targets in Italy because the rail lines were close to population centers capable of providing labor for repair and were close to repair facilities and their materials.

Marshaling yards were also difficult to block as all tracks and sidings had to be eliminated to render them inoperable. By Twelfth Air Force calculations, such complete blockage of a medium-sized marshaling yard required 425 tons of bombs for a four- to eight-hour blockage versus 196 tons for a bridge blockage, which might take longer to repair.

Additionally, the report noted that the yards were not vitally important to the Germans because they could repair a single line and use through trains direct from Germany to the front to transport supplies without having to transfer cargo in marshaling yards.

Lastly, destruction of marshaling yards destroyed rolling stock that could be useful to support the Allied advance once the Gustav Line had been breached. This failure to assess the resiliency of the German/Italian rail system was a major intelligence error.

Counting their own considerable railroad assets and the captured rolling stock from conquered countries, the Germans at the beginning of 1944 had thousands of locomotives and a million boxcars available. The capability of the Germans to run trains on one-way trips direct from Germany to southern Italy largely negated the critical nature of marshaling yards in their ability to support their forces in Italy.

A Shift in Tactics: More Bridges, More Loiter-Time

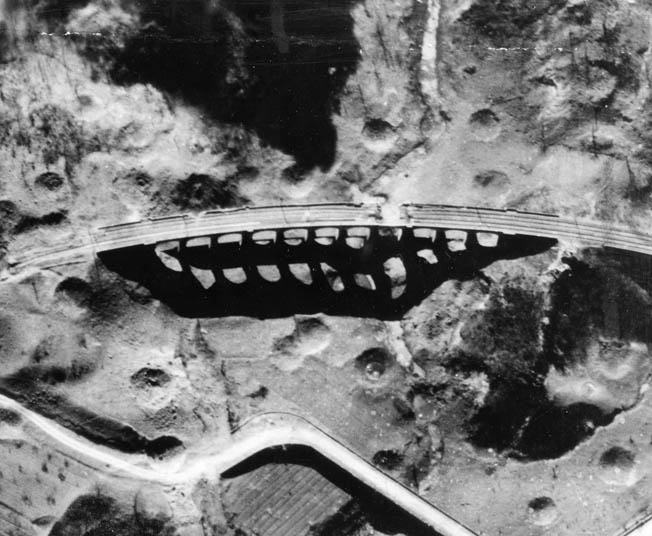

Shortly after Strangle began, General Eaker noted that attacks on bridges seemed to be more effective than those on rail yards. Based on operational reports, MAAF intelligence officers found that damage done to bridges was harder and took longer to repair than damage done to rail lines. As a result, Eaker shifted the emphasis, particularly for medium bombers and fighters, more and more toward bridges.

In fact, the fighter bomber came to be seen as the weapon of choice for bridges. It could fly in weather that grounded the medium bombers, which needed high ceilings to acquire the target and drop their payloads from a horizontal delivery. From a high-level, horizontal delivery, at best only one bomb per bomber had a chance of hitting a target as narrow as a bridge or road due to “ripple release.”

Fighter bombers utilizing dive bombing deliveries came to average one bridge destroyed for every 19 sorties versus 31 sorties for the same effect from medium bombers. This shift to bridge busting was not only a more efficient use of sorties and bombs but, due to the mountainous topography of Italy, dive bombing was the only reliable delivery for small point targets such as bridges.

An intelligence summary distributed to fighter bomber units at the start of Strangle stated that 1,000-pound bombs were the preferred weapon against bridges to ensure sufficient structural damage to bridge abutments and supporting piers.

Medium bombers were incapable of dive bombing, and the P-40, A-36 (P-51A), and P-39 were mediocre dive bombers at best, as the P-39 and P-40 could not carry a 1,000-pound bomb and the A-36 had severe range restrictions carrying just one.

The real increase in effectiveness of the interdiction campaign can be traced to the introduction of significant numbers of Republic P-47 Thunderbolts in theater in December 1943. The P-47 was ideally suited to dive bombing. Heavily armed, stable in a dive, and sporting a huge radial engine that protected a pilot from ground fire while carrying up to 2,500 pounds of bombs, the P-47 bore the brunt of the bridge-busting missions against targets south of Florence.

With the shift of targeting emphasis from marshaling yards to bridges, the focus of the operation changed from an interdiction zone belt running from the east to the west coast between Florence and Rome to the area south of Rome to allow for fighter bombers to carry heavier payloads and loiter longer in search of targets from their bases in southern Italy. This also allowed a concentration of photoreconnaissance assets and more frequent coverage of all roads and railroads.

The “Night Operational Bridge”

The MAAF, by the spring of 1944, had photo mosaics covering the entire Italian peninsula that highlighted roads, marshaling yards, bridges, ammo dumps, troop concentrations, and gun positions. The three reconnaissance groups allowed MAAF to photograph each possible target every 72 hours, weather permitting.

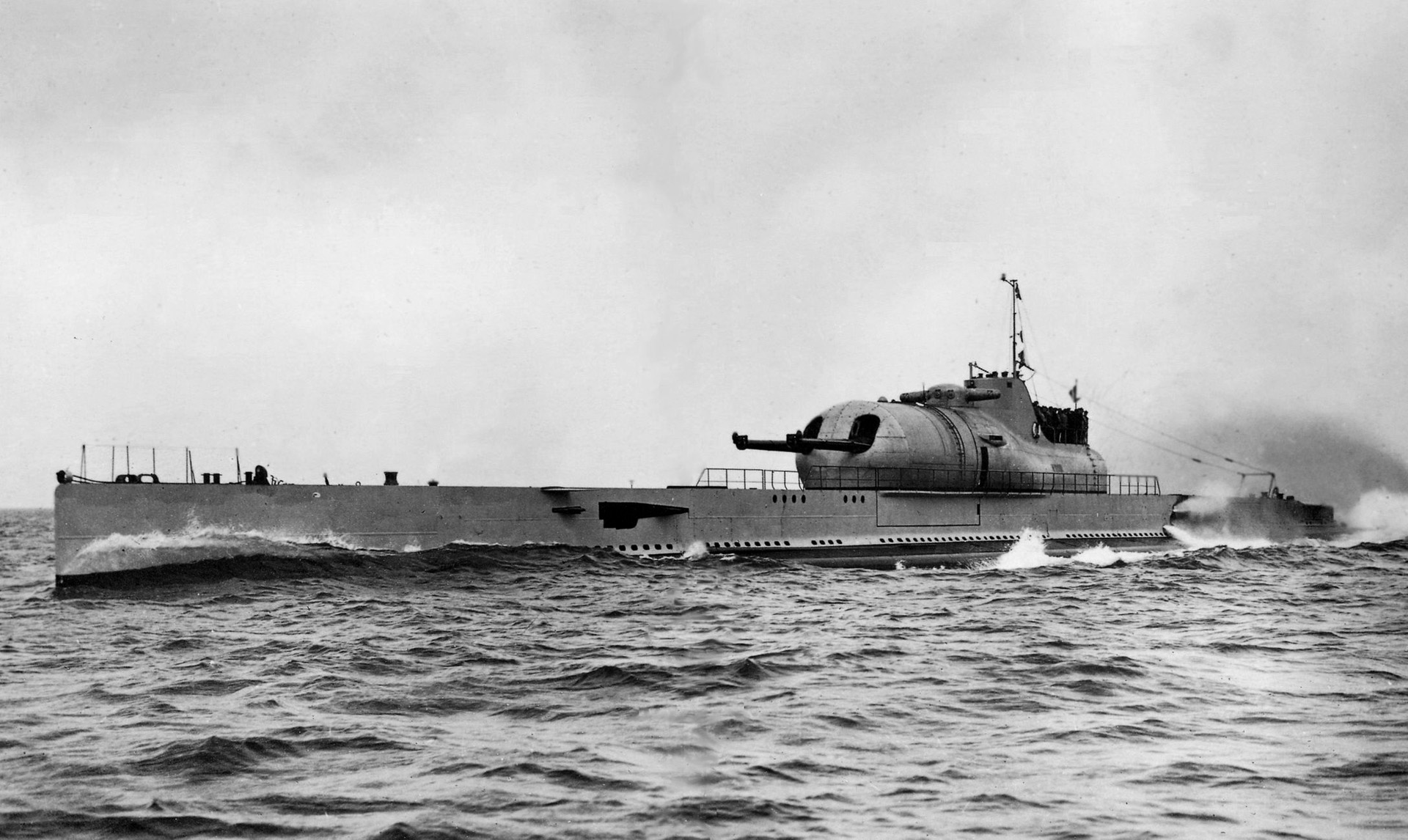

While no doubt a valuable tool, the MAAF came to overrely on photo intelligence. While photos appear to give unmistakable information, the Germans were great practitioners of deception. One technique was the “night operational bridge.” The Germans would repair a bridge, leaving one span that was visible to photo reconnaissance as a cut bridge. At night, a temporary span would be erected for vehicle or rail movement and then the span would be removed before daylight.

Likewise, the Germans used pontoon bridges that were hidden during the daylight to span rivers at night and, when the Po River bridges were all cut in the spring of 1945, the Germans used pipelines to carry their petroleum products across the river. As determined as the Allied effort was to interdict supplies, bad weather and the cover of night greatly reduced its effectiveness.

Breaking Through the Gustav Line

As the proposed start date for the 1944 spring offensive on the Gustav Line approached, it became apparent to Strangle’s most ardent proponent that the interdiction campaign was not achieving its objective of forcing the Germans to withdraw. General Eaker’s deputy, RAF Air Marshal John Slessor, noted his concern in mid-April that the German supply situation had not become desperate due to “frugal” German living conditions, their ingenuity at making adaptations in their supply system, and poor flying weather.

While it was becoming apparent that Strangle’s objectives would not be met, MAAF did not have a Plan B for use of its resources. It continued to pursue the air interdiction countersupply strategy of Strangle by shifting the focus of its air attacks closer to the Gustav Line, hoping that, once the ground campaign began and the enemy’s supply requirements increased, the air interdiction would at last realize its goal.

With confidence that airpower had achieved its objective of making the Germans’ hold on the Gustav Line untenable, General Harold Alexander ordered Operation Diadem to commence on May 11, 1944.

As a collateral effect of Strangle’s interdiction campaign, air power had effectively isolated the German Army from its major source of supplies, and the constant of attrition of vehicles, bridges, and roads drastically hindered Kesselring’s ability to move his forces laterally to reinforce weak areas and to close breakthroughs.

Lack of lateral mobility coupled with an Allied deception campaign that threatened an amphibious landing north of Rome prevented Kesselring from shifting forces to confront Allied penetrations and to bring up his limited strategic reserve from the vicinity of Rome.

With Hitler’s orders to stand his ground, Kesselring’s options to stem the Allied assault on and penetration of the Gustav Line were limited. The stress of ground combat on the German Army finally yielded evidence of the effectiveness of the air campaign on its combat capacity.

While the U.S. Army’s history notes that the collapse of the German right flank on the Tyrrhenian Sea was precipitated by the overwhelming firepower of American artillery, the MAAF saw the retreat of German troops as a delayed reaction to the effectiveness of Strangle.

Regardless of the difference of opinion as to what arm was responsible for finally rupturing the Gustav Line, the effects of the air interdiction campaign were unmistakable. The rear of Army Group C was a shambles. Beyond the range of artillery, the Twelfth Air Force had chewed up roads, dropped bridges, destroyed vehicle and animal transport forced to travel in daylight, and eliminated railroads as viable transportation south of Rome.

Faced with multiple ruptures of his main defensive line, Kesselring was finally forced to withdraw. Forced into the open and limited in mobility, the retreat of his two armies turned into a near rout. From the abandonment of the Gustav Line to the Rimini-Pisa line, codenamed Gothic, 200 miles to the north, Kesselring lost 70,000 men—30 percent of his forces. Forced from dug-in positions and slowed by the loss of motor transport and interdicted lines of communication, his forces were prey for Allied fighter bomber attacks.

The Allies Shift Momentum

On the surface, it would appear that the dislodgement of Army Group C from the Gustav Line and its 200-mile retreat to the Gothic Line would have been a disaster for the Germans. With complete air superiority, longer periods of daylight, better weather, and an enemy in the open, Alexander should have been able to destroy Kesselring easily.

However, with the shift of divisions to Operation Anvil-Dragoon–—the Allies’ invasion of southern France in August 1944—coupled with four new German divisions assigned to Kesselring, the effect on the Italian campaign was disastrous. The pursuit of a routed enemy was essentially called off.

This gift from the Allies allowed Kesselring to retreat to the Gothic Line and, in an identical fashion, sit out the winter of 1944-1945 entrenched in fortified mountainous terrain and stalemate the Allied advance. While Kesselring lost a significant portion of his troops on the retreat northward, he was able to keep his understrength formations together as effective fighting units and delay a desultory Allied pursuit.

Part of the reason for the less than vigorous pursuit of the retreating Wehrmacht was the Germans’ excellent use of demolitions and mines to slow the Allies. Additionally, Alexander, like all British senior generals, clearly remembered the slaughter of the Great War and the psychological impact it had on the British public. As a result, British Army units moved slower and with more caution than did American units. They also emphasized firepower to the maximum extent to degrade enemy formations rather than direct combat.

Mark Clark was also cautious in pursuit. Following his single-minded obsession with capturing Rome, the rest of the campaign was almost anticlimactic for him.

Following Diadem and the breakthrough of the Gustav Line, the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) informed Alexander that support for Operation Anvil-Dragoon would become the priority for the Mediterranean Theater, and assets to support the operation would come at the expense of Alexander’s forces. By the end of June 1944, SHAEF stripped Alexander of three U.S. and two French divisions along with six P-47 fighter groups. In July, an additional seven divisions were removed from Italy.

U.S. Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall had agreed with SHAEF’s strategy of shifting the emphasis in the Mediterranean Theater from Italy to southern France, and concurred with stripping Clark of his best divisions. Additionally, until the Americans could repair the port at Livorno to supply the Allies’ push north, logistical problems caused by having to move supplies from Naples over 200 miles of broken roads and cut rail lines necessitated the Allied advance’s slowdown.

Why was Strangle not an overwhelming success?

First, faulty intelligence. Allied intelligence misjudged the availability and redundancy of the German rail system. With 63,000 locomotives and over a million boxcars, the Germans had the luxury of sending their trains on one-way trips to the front and obviate the need to run train traffic in two directions. Also, intelligence officers and Allied planners had a preset idea of the effectiveness of an air interdiction campaign, and their reliance on 8×10 black-and-white photographs of bomb damage did nothing to dissuade them.

Second, technology. By 1944, the U.S. Army Air Forces constituted the largest and most technologically advanced air force in the world. Barring the relative handful of German jet and rocket fighters, the bulk of the USAAF was superior qualitatively and quantitatively to any air force, especially with respect to bombers.

One key qualitative advantage was the Norden bombsight on heavy and some medium bombers. So secret was the Norden that it was taken from a vault before each mission and returned afterward; bombardiers took an oath to protect the bombsight from falling into enemy hands in the event of a forced landing.

Despite the fact that the Norden bombsight was the most accurate in the world, it was not as accurate as advertised. The Norden was a primitive analog computer bombsight that took inputs of the aircraft’s altitude, winds aloft, true airspeed, and type of bomb carried (for ballistic calculations) to compute drift due to winds and air density and to predict a release point that allowed a bombardier to “put a bomb in a pickle barrel from 20,000 feet.” In practice, Norden-guided bombing was much less precise.

In October 1943, the Eighth Air Force launched 250 bombers against the ball bearing works at Schweinfurt, Germany, where only 10 percent of the bombs landed within 500 feet of their aiming point. While this accuracy may have been adequate for area targets, Norden-equipped B-26s took over 40 sorties—with each aircraft dropping three bombs—to hit a single bridge during Operation Strangle.

For fighter bombers such as the P-47, the problem was more low tech. A dive bomb delivery required the pilot to set his gunsight for the proper amount of “mils” (i.e., milliradians of depression of the sight from level) based on the ballistics of the bomb, the dive angle, and release altitude.

The pilot had to visually acquire the target, roll into his dive, and set his gunsight reticle the proper distance short of the target. As he approached the target in a dive, the gunsight moved closer to the estimated release point. The pilot applied “combat offset” for the estimated winds and rechecked his dive angle. For the sight picture to be valid, the g forces on his aircraft during the dive had to be the cosine of the dive angle.

For example, a 45-degree dive bomb delivery required 0.707 gs to be maintained. This was all done through experience and seat-of-the-pants sensation. At release altitude, the gunsight needed to be offset the proper amount into the wind, and the bomb was released. If everything was perfect, a direct hit was scored, but that was seldom the case.

While level bombers attacked bridges 90 degrees perpendicular to their long span to have a better chance of getting a hit from their string of bombs, the fighter bomber pilot attacked along the longitudinal axis of the bridge with his single bomb since most dive bomb errors are long or short. Since single-span bridges were usually less than 30 feet wide, misses were frequent and collateral bomb damage was minimal.

Third, weather. Adverse weather had a major impact on the operation. During the March-May 1944 period of Operation Strangle, approximately 45 percent of medium bomber sorties and 39 percent of fighter bomber sorties were noneffective due to weather. These were sorties that were either cancelled due to weather below minimums for takeoff or clouds obscuring the primary and alternate targets.

No aircraft involved in Strangle possessed even rudimentary radar bombing capability such as the Eighth Air Force and RAF Bomber Command were using in northern Europe. Ordnance could only be expended on targets that were visually acquired. This limitation was also a factor at night. General Eaker complained that tactical air forces were never allocated sufficient quantities of flares for night bombing, and as a result night bombing attacks were infrequent and of little value. A daily operational summary for April 25, 1944, reported that a night attack by eight RAF Bostons (USAAF A-20 twin-engine light bomber) and 36 B-26s on the road complex and railroad bridge at Subiaco (southeast of Rome) resulted in no roads obstructed, no hits on the bridge, and only “superficial” damage to one road due to a near miss.

These limitations in all-weather attack capability were significant factors in hampering the success of the operation. During the spring in northern Europe, the lengthening days still provide 11 hours of darkness per night. This, coupled with frequent bad weather during the day, allowed the Germans a sanctuary to repair road and bridge cuts and operate their motor transport in daylight.

Allied intelligence estimated that a direct hit on a rail line by a 1,000-pound bomb resulted in a crater 16 feet wide and five feet deep—a crater that took the enemy only four to six hours to repair. Similar to the analogy of a man shoveling sand, he must shovel faster than the rate of sand filling the hole in to make progress. Aircraft, crews, and munitions were available for the Allied interdiction task, but what was not available were sufficient favorable weather conditions to disrupt enemy supply routes faster than the Germans could make repairs to maintain a minimal resupply capability.

Fourth, assessment. Operation Strangle’s results were a mixed bag of opinions. The overall Allied commander in the Mediterranean, Field Marshal Alexander, gave tepid praise to the operation as “aiding” the breakthrough of his armies from the Gustav Line. General Clark, frustrated by dogged German resistance to his drive on Rome, flatly declared all air interdiction, including Strangle, “a flop.”

Official Praise For Operation Strangle

The commander of Strangle, General Eaker, was enthusiastic in his praise for his commanders and aircrews that “forced the withdrawal” of German forces along the Gustav Line. The commander of Army Group C, Albert Kesselring, complimented the Allied air effort but claimed his “supply situation was satisfactory” during the Italian campaign. The two supreme commanders, Allied and German, probably had the best view and most accurate overall assessment of the March to May 1944 period of Strangle.

Not surprisingly, the official history of the U.S. Army Air Forces overstated that “Operation Strangle completely stopped rail traffic south of Rome.” In addition, the history lists tremendous amounts of railroad rolling stock destroyed and vehicles damaged and destroyed on highways. Although the official history documents the damage done by Strangle, it does not measure its effectiveness against its objective: to force the Germans to cease military operations due to lack of supplies.

Neither does the official history give an insight into the effect of the interdiction campaign on its intended victim, the German Army. It intimates that it completely stopped all rail traffic south of Rome and thereby cut off all supplies to Kesselring’s forces. The official history focuses on hard numbers: sorties flown, tonnage of bombs dropped, rolling stock destroyed, bridges destroyed, enemy aircraft shot down, and paints a one-sided picture of the operation. It is more of a numerical summary of the effort expended than an in-depth analysis of Strangle’s effectiveness.

Did Strangle change German defensive tactics or shorten the war in Italy? It could have but did not due the previous errors discussed, an increase in German reinforcements, and an overcautious Allied ground strategy.

In assessing the impact of Strangle and the entire war in Italy, one overriding factor to be considered is that the war in Italy was considered by both sides to be a sideshow to the decisive campaigns on the Eastern and Western Fronts. There was no “On to Berlin” mood for the Allies, and the German troops there were fighting far from home on foreign soil.

The Allied forces in Italy also became a dumping ground of sorts for divisions that other theater commanders did not want. Some of these units fought well, such as the U.S. 10th Mountain Division. The 10th was assigned to Italy where its logistical requirement for its hundreds of mules proved to be an extra strain on quartermasters.

Likewise, the Nisei 100th Regimental Combat Team, composed of Japanese Americans, distinguished itself in battle. Other units such as the Brazilian Expeditionary Force, the Jewish Hebron Brigade, Canadian, South African, New Zealand, Royalist Italian, Rhodesian, Polish, Indian, Gurhka, and the African American 92nd Division troops added to the friction of command of such a cross-cultural and polyglot group.

Strangle did not reach its ultimate objective of starving the Germans of support during their occupation of the Gustav Line, due in part to the Allied ground forces not pressuring Kesselring into expending his consumables. Similarly, the slow pursuit of the German armies by Alexander relieved the pressure of an enemy nipping at his heels and allowed Kesselring precious time to conduct an orderly withdrawal.

Operation Mallory Major

The Allies implemented a replay of Strangle in August and September 1944 in an attempt to cut off Kesselring’s forces from resupply prior to his reaching the Gothic Line. This interdiction operation was codenamed Mallory Major, and its results were similar to Strangle’s. Tactical air forces did an excellent job of cutting all the bridges over the Po River and denied Kesselring’s troops any supplies for a time. However, the lack of air and ground joint planning negated the success of this interdiction campaign.

Mark Clark was not ready to attack at the end of Mallory Major and, coupled with the withdrawal of troops for southern France, caused a near cessation of interdiction sorties for six weeks. This respite allowed the resourceful Germans time to lay pipelines across the Po and establish sufficient pontoon bridges and shallow underwater crossings to keep supplies flowing. Mallory Major, like Strangle, became more of a harassing campaign than a decisive military blow.

Yet, the Army Air Forces learned a lesson. Interdiction must be continuous to be effective. Following the breakthrough of the Gustav Line, the majority of combat sorties were shifted to close air support of Fifth and Eighth Armies with minimal resources allocated to interdiction. Following the breakout from the Gothic Line, tactical air planners continued to hammer retreating German troops on the flat, open terrain of the Po Valley, turning an orderly retreat into a rout.

Like Strangle, Mallory Major received lukewarm praise from Alexander and Clark. Tactical air intelligence, which had learned some lessons from overly optimistic reporting of Strangle results, reported that Mallory Major had limited success. “Despite its width, the Po River failed to halt the flow of supplies after its bridges had been destroyed in Operation Mallory Major, and the lesson was demonstrated anew that multiple barriers are necessary to effectively undo the enemy’s logistics.”

However, the Germans were much more emphatic in assessing the effectiveness of what was essentially Strangle Part II.

General Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin, commanding general of XIV Panzer Corps, admitted, “The Allied bombings of the Po River crossings finished the Germans in Italy.” Pressed by constant daylight air attack and attack by night under flares, the Germans were forced to abandon most of their equipment and the disorganization caused by hurried river crossings caused unit cohesion to disintegrate. General von Senger added, “North of the Po, we were no longer an army.”

Lessons of Operation Strangle

The problem with assessing Strangle’s effectiveness lies in the fact that it was an exclusive Army Air Forces show that was dependent upon ground troops to assist in keeping constant pressure on the enemy. In that way, such repeated blows against the German supply system would be magnified by the increased consumption during daily fighting and erode German combat effectiveness. It was an operation that was too optimistic in its scope.

Never before had such an intensive interdiction campaign been conducted, and the methods to assess its progress were invented on the fly. Operational Research scientific methods predicted success based upon skimpy data from campaigns that were not similar to the conditions in Italy. Overreliance on photo intelligence painted a false picture of the progress of the campaign.

Finally, the technology of the day did not permit a continuous application of air power against the enemy’s logistical network, allowing many hours or days of sanctuary from air attack for a resourceful enemy to react and adjust. Many of these same lessons were relearned some 25 years and half a world away during the interdiction campaign against the North Vietnamese supply line on the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Ultimately, measured by Operation Strangle’s objective as directed by the Combined Chiefs of Staff to “reduce the enemy’s flow of supplies to a level which will make it impossible to maintain and operate his forces in central Italy,” Strangle must be judged as having failed to meet its objectives. As effective as it may have been in harassing the enemy, it did not shorten the war. German forces in Italy surrendered on May 2, 1945, just days prior to the capitulation of the Third Reich.

Great read, lots of good research.