By Jon Diamond

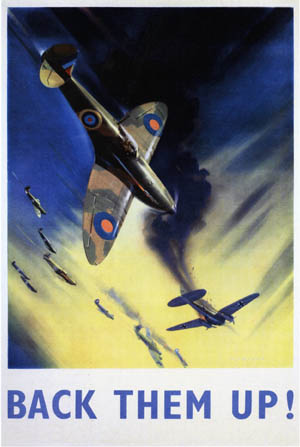

In the summer of 1940, the vaunted Luftwaffe, fresh from its victories in the skies of France and the Low Countries, began its aerial assault in an attempt to either bring Britain to “peace” terms or destroy the Royal Air Force as a prelude to Operation Sea Lion, the invasion of southeastern England.

Britain’s hope, after its army had been routed in France and Belgium, rested on “The Few”—a cadre of British, Commonwealth, American, and other émigré fighter pilots of the RAF. The man leading Fighter Command was a resolute, embattled air marshal nicknamed “Stuffy,” who fought Winston Churchill and nearly every other minister and general in a variety of political campaigns during the prewar years. His goal was to achieve a strategy focused on radar detection, safe and reliable ground-to-ground (as well as ground-to-air) communication, and high-performance, single-seat, monoplane fighters—the Hurricane and the Spitfire.

To paraphrase David Fisher, “This was also a man whose mind broke from the strain at the height of the battle, who talked to the ghosts of his dead pilots, but who nevertheless was able to keep another part of his mind clear enough to continue making the daily life-and-death decisions that saved England” from the Luftwaffe’s daytime onslaught during that beautiful summer of 1940. Unfortunately, the name of Fighter Command’s leader during the Battle of Britain is becoming increasingly eclipsed with the passage of time and attempts at revisionist history.

What was the intrigue surrounding the maladaptive relationship between Air Chief Marshal Hugh Caswall Tremenheere Dowding, commander in chief of Fighter Command, and one of his principal subordinates, Vice-Air Marshal Leigh Trafford-Mallory?

The basis and mysterious circumstances of this malicious hierarchal relationship involved political in-fighting, vanity, and conspiracy at a time when Britain was literally battling for its life. According to Robert Wright, “For many years the name of Dowding was allowed to remain in those shadows that were created for him by lesser men. From time to time some lip-service was paid to his achievements; but a truly equitable recognition of what Dowding achieved at the time of the greatest peril to our way of life has never been fully accorded him.”

An Aviator of the First World War

Hugh C.T. Dowding was born on April 24, 1882. From the very beginning Dowding had shown marked tendencies toward forthright expressions of his own views but he learned to contain them and to express them only at the right time and to the best effect. Dowding described himself: “Since I was a child I have never accepted ideas purely because they were orthodox, and consequently I have frequently found myself in opposition to generally accepted views. Perhaps, in retrospect, this has not been altogether a bad thing.”

In 1909 Dowding, while commanding a Native Battery (Dowding was originally a gunner from the Royal Military Academy, Woolich) in India, met a man who was to play a vitally important role in his life in the Battle of Britain in 1940: Cyril Newall, a subaltern commanding Gurkhas. After six years of service in India, Dowding returned to England to attend the Staff College course at Camberley, which was to last two years. While there, Dowding noted, “I was always irked by the lip-service that the Staff paid to freedom of thought, contrasted with an actual tendency to repress all but conventional ideas.”

In his transition from the Army to the Royal Flying Corps, Dowding attended a pilot-training course at the Central Flying School at Upavon. There, in early 1914, Dowding met Major Hugh Trenchard, who was to become one of the founding members of the RAF. In the spring of 1914, Dowding received his wings as an accredited pilot in the Royal Flying Corps.

By the end of the war in 1918, when Dowding was a brigadier general, principal characters in this upcoming story of political intrigue within the RAF during the Battle of Britain were Charles Portal, Sholto Douglas, Keith Park, and Trafford Leigh-Mallory, all of whom were majors in command of squadrons. Cyril Newall was also a brigadier general, and one of the leading proponents of the use of bombers.

Dowding vs Leigh-Mallory

Of this group, one of Dowding’s main antagonists was Trafford Leigh-Mallory. Leigh-Mallory was born in Cheshire in 1892, the son of a rector. He was educated at Magdalene College, Cambridge, earning an honors degree in history prior to becoming a barrister in 1914. During World War I, Leigh-Mallory joined the Liverpool Regiment as a private but was soon commissioned and transferred to the Lancashire Fusiliers. In 1915, he was wounded at the Second Battle of Ypres and joined the Royal Flying Corps in 1916 after recovering from his wounds; he became a pilot flying bombing and reconnaissance missions during the Battle of the Somme.

Noted for his energy and efficiency by his superiors, Leigh-Mallory’s subordinates regarded him as distant and arrogant. After the war, he was briefly an inspector of recruiting prior to moving to the School of Army Cooperation, where he became its commander from 1927 through 1931. He then moved on to the Air Ministry and, in 1934, commanded the first flying school at Digby. In need of a posting overseas for career advancement, Leigh-Mallory served in Iraq and was then recalled to England in 1937 as war loomed.

Dowding became the first commander in chief of Fighter Command after completing his assignment as air member for research and development where he provided oversight for the development of the Hurricane and Spitfire fighter aircraft and the emerging technology of radar. In July 1938, Dowding was notified by the chief of the air staff, Cyril Newall, that, in Dowding’s words, “my services would not be required after the end of June 1939.” Dowding and Newall were contemporaries, with Dowding slightly more senior, but nonetheless had been passed over for the chief of the air staff position. According to Dowding, “I’ve always been against all governments. Wherever I’ve been, and in whatever I have tried to do, it seemed that there was always somebody in the Government who was hampering my efforts.”

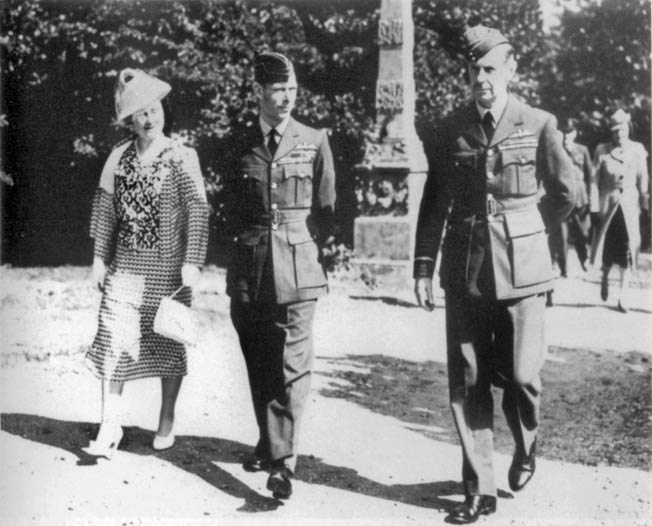

In the summer of 1938, New Zealander Keith Rodney Park became Dowding’s senior air staff officer, working directly with him at the headquarters of Fighter Command. These two officers were in complete harmony in their understanding of the development of Fighter Command as a major arm of defense against a projected attack from the Luftwaffe.

In 1937, Trafford Leigh-Mallory became air officer commanding No. 12 Group, to the north of what would become Park’s command at No. 11 Group. These two men became Dowding’s most important subordinates. Park was to exhibit the utmost loyalty to Dowding; conversely, Leigh-Mallory would give Dowding some of his gravest difficulties.

As a means of background for this disharmony between these RAF commanders, soon after Air Marshal Hugh Dowding became the commander in chief (C-in-C) of Fighter Command in 1936, he expected that No. 12 Group (north of the Thames) would bear the brunt of any attack from Germany based on geographical lines. To command this important group, in 1937, he chose Leigh-Mallory, now an air vice-marshal—to his everlasting regret.

Clash Over “Big Wing” Tactics

At this juncture, Leigh-Mallory was an imposing man reputed to be unwilling to tolerate others’ opinions. Although he had the traits of a good commander, Leigh-Mallory expected that he would lead the defenses wherever the Germans might attack. After the fall of France, it was apparent that the upcoming air battle would be heavily contested in the area of No. 11 Group in the southeastern corner of England, so Leigh-Mallory asked for an immediate transfer to this command. However, Dowding had greater confidence in Air Vice-Marshal Park, with whom he had already worked at Fighter Command. Thus, he kept Leigh-Mallory north of the Thames and allowed Park to command No. 11 Group. Leigh-Mallory and Park detested one another and this decision would come back to haunt Dowding.

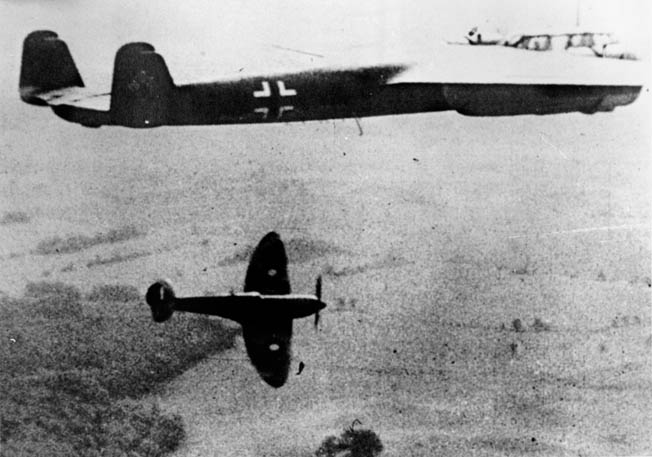

The blunt fact was that Leigh-Mallory was jealous of Park’s role as the Group Commander defending the area that was to be the most heavily engaged with the Luftwaffe since, after France’s fall, Nazi airfields were now just across the English Channel, 20 miles away. Also, the two group commanders held different tactical views. Park agreed with Dowding’s strategy of sending up small flights of fighters to attack very large Luftwaffe forces in order to husband his outnumbered RAF fighters and pilots, thereby forestalling Operation Sealion, Germany’s planned invasion of Britain.

By actively avoiding a major clash with the Germans, Dowding sought a steady level of Luftwaffe attrition that would preclude Nazi control of the air prior to an invasion. Leigh-Mallory thought this fighting method was nonsense. By attacking with the strongest concentrations of aircraft—“Big Wings”—Leigh-Mallory believed he could clear the skies of the Luftwaffe and reduce casualties among the RAF pilots.

Controversy over “Big Wings” had been raging for some time in Fighter Command. In addition to Leigh-Mallory, one of the most vociferous advocates of the “Big Wing” tactic was the leader of Squadron No. 242, Douglas Bader. This tactic entailed the in-air assembly of an entire wing of five squadrons to attack the enemy bombers in force.

Dowding rejected Leigh-Mallory’s “Big Wing” method for two reasons. First, the RAF did not have to defeat the Luftwaffe in massive aerial duels. In a battle of attrition, the RAF only had to avoid being defeated. Leigh-Mallory’s tactic would have resulted in gigantic, pitched air battles between the two air forces, which was Luftwaffe chief Hermann Göring’s goal and an anathema to Dowding.

Another reason Dowding vetoed the “Big Wing” tactic was that it took too long to bring large formations of fighters together; Fighter Command’s airfields were too small to allow several squadrons to take off simultaneously. Thus, individual flights of three planes would take off and then wait to form up with the later ones to establish the “Big Wing.” Dowding’s radar system was not able to provide a proper time interval for such an aerial flight assembly. The German bombers would have reached their targets and unloaded their bombs before the “Big Wing” caught them.

“Nonsense,” scoffed Leigh-Mallory. “All it takes is practice. And even if this were true,” he continued, “so what? We’ll hit them so hard that they won’t come back again.” In the event, it often did prove true that the “Big Wing,” when employed by Leigh-Mallory, was too late to intercept the bombers before they hit their targets.

The Continuing “Big Wing” Controversy

Leigh-Mallory was Dowding’s subordinate and thus a debate about the “Big Wing” tactic should have been brief. Leigh-Mallory should have followed his orders to be a backup to Park’s No.11 Group. Dowding’s biggest mistake was not to crack down on Leigh-Mallory. Long after the personal battle was over, Dowding reflected, “Looking back on things now, I believe that I ought to have been very much firmer, in fact stricter, with Leigh-Mallory.” Dowding might have considered replacing Leigh-Mallory at this time, but his attitude was to pick the best people and to delegate responsibility. His assumption that Leigh-Mallory would simply follow his orders turned out to be unrealistic and incorrect.

After a fighter defense exercise in 1939, Leigh-Mallory started instituting standing patrols on his own initiative. Dowding disagreed and warned Leigh-Mallory not to implement strategic changes without orders. Leigh-Mallory objected to this admonition and left the meeting ranting that he would “move heaven and earth to get Dowding sacked from his job.”

As the Battle of Britain raged on, Douglas Bader vehemently stirred his squadron’s pilots into a frenzy for their inactivity. Leigh-Mallory should have restrained Bader but instead he encouraged the insubordinate behavior. Leigh-Mallory told Bader that he could ignore any orders emanating from No. 11 Group (Park) or even Fighter Command (Dowding). Dowding should have intervened and disciplined Leigh-Mallory (and Bader) as he had after the air defense exercises in 1939. At that time, when Leigh-Mallory had tried to insist on his right to override Fighter Command orders, Dowding told him, in front of other senior officers, “The trouble with you, Leigh-Mallory, is that sometimes you cannot see further than the end of your little nose.”

The second controversy that swirled around the “Big Wing” tactic was the disagreement, dating from prewar days, between the Air Ministry and Fighter Command over the most effective way to intercept raids made by large enemy formations. Dowding’s opponents at the Air Ministry, who considered him to be uncooperative and unsuited to his command, seized eagerly on others who disagreed with his policies. In this way, Leigh-Mallory and Bader were essentially used as pawns in the “Big Wing” controversy by an Air Ministry upper echelon critical of Dowding.

The Air Ministry “brass” shrewdly noted that No. 12 Group’s theories were useful to discredit both Dowding and Park. Prominent among Dowding’s opponents was Air Marshal Sholto Douglas. A staff officer noted that during the Battle of Britain there was little telephone conversation between either Leigh-Mallory and Dowding or Leigh-Mallory and Park, though there was “plenty between Leigh-Mallory and Sholto Douglas.” This same RAF officer believed that Douglas was an eminence grise for Leigh-Mallory, working in the shadows of the Air Ministry to surreptitiously undermine Dowding.

In regard to the “Big Wing,” Leigh-Mallory submitted a report to Dowding on Wing Patrols, which was forwarded to the Air Ministry. Leigh-Mallory wrote that, on the morning of September 15, 1940, the Wing, “on finding the Dorniers were able to destroy all they could see … promptly destroyed the lot.” He went on: “The enemy were outnumbered in the action and appeared in the circumstances to be quite helpless.” Leigh-Mallory claimed 105 destroyed, 40 probably destroyed, and 18 damaged, for the loss of 14 RAF aircraft and six pilots. Douglas got these figures and they were just what he had been looking for.

Intriguingly, not all the pilots in No. 12 Group approved of “Big Wings.” A Flight Lieutenant Blackwood had observed “that it was often chaos.” Flying Officer Brinsden thought the Big Wing a “disaster,” which achieved nothing because, in any case, “the [Big] Wing disintegrated almost immediately when battle was joined.”

Dowding Removed From Fighter Command

A special meeting was arranged for October 17, 1940, by Cyril Newall, chief of the air staff (CAS). The immediate agenda was to discuss the disagreement in fighter formation tactics, and to review the progress on night defense as the “Blitz” was intensifying. Although held in Newall’s office, the CAS was taken sick at the last minute and the chair was taken by the deputy chief, Sholto Douglas. Dowding showed up expecting to give the Air Ministry a summary of his strategy in the battle, which he had just won, and to discuss the progress with radar for night interception.

To Dowding’s dismay, Squadron Leader Bader was there among the assembled air marshals and air vice-marshals. Leigh-Mallory had brought him so the Air Ministry could hear the views of an actual fighting pilot. However, Sholto Douglas did not solicit the views of other squadron leaders who felt that the “Big Wing” concept was wrong. When Air Marshal Portal, who seems to have been the only skeptic in the room with regard to “Big Wings,” asked Leigh-Mallory how he could defend his local area if all his strength were so concentrated, the latter assured him that “satisfactory plans were prepared.”

Sholto Douglas then took the floor and essentially presented Bader’s and Leigh-Mallory’s views as the preferred tactic and inquired why it should not be utilized to its fullest effect. Thus, Dowding was effectively put in the position of refuting the charge. Leigh-Mallory took the floor and said he could get the “Big Wing” into formation within six minutes. No one asked him why, during the past summer, it had always taken more than a quarter of an hour to do so, resulting in the Wing always being too late to engage the bombers before they reached their targets. Instead, he repeated Bader’s lecture on the simple values of overwhelming force, and the assembled audience very nearly broke into hearty applause.

In essence, the room was stacked, and Dowding was ambushed. The official stance of the Air Ministry was that the Battle of Britain had been mishandled by Dowding. According to Keith Park, Dowding was condemned by this meeting with the controversy over “Big Wings” being an excuse to dismiss him from Fighter Command’s leadership.

To complete the piling-on, Dowding was ordered by the Air Staff to immediately use Hurricanes in night defense rather than waiting months for his preferred radar-equipped Beaufighters. Predictably, the Hurricanes failed but, nonetheless, Dowding was fired three weeks after this fateful meeting. Preditctably, Sholto Douglas became the new commander of Fighter Command. To Dowding’s credit, night defense succeeded when the Beaufighter with airborne radar was ready the following spring.

The Salmond Committee

Unfortunately for Dowding, though, another powerful lobby had convened and believed Fighter Command’s C-in-C was absolutely wrong. Although a political ally, Lord Beaverbrook, minister of aircraft production, intervened on September 14, 1940. He wrote to Archibald Sinclair, minister for air, to inform him that a committee was to be formed to look into night defense under one of his staff, a former CAS, Marshal of the RAF, Sir John Salmond.

The “Salmond Committee” produced its report within days and was critical of Dowding while substantiating Douglas’s views on night defense. Salmond even attached a private note to Beaverbrook’s copy of the report recommending that “Dowding should go.” He added that he had said the same thing to Churchill, who practically blew him out of the room, but was “coming round.” If Churchill failed to sack Dowding, Salmond was prepared to go to the king.

Seven Reasons For Dowding’s Dismissal

Why was Dowding removed as C-in-C of Fighter Command after having been victorious in the Battle of Britain? Who was principally responsible for his demise? Although Dowding had generated considerable enmity among his peers and superiors during his decades with the RAF, he was not devoid of political allies. He got along well with Neville Chamberlain in 1937 since the prime minister had moral reservations about bombing and, thus, insisted that air rearmament prioritize fighter defense.

Prior to the “Salmond Committee,” Dowding also had the support of Lord Beaverbrook. Churchill, too, recognized the vital contribution Dowding had made to Britain’s defenses. Early on, Churchill saw the need to postpone Dowding’s forced retirement—but only for as long as the direct threat to Britain was there. Churchill expected Hitler to turn east once his attack on Britain had been broken; then, his only method to attack Germany directly was with the bomber. Once the defensive battle of July-October 1940 had been won, Churchill could feel comfortable in releasing Dowding from Fighter Command.

According to historian John Ray, there were seven reasons why Dowding was replaced in November 1940. Three existed before the Battle of Britain started and included his age (58 years), his tenure of four years as C-in-C Fighter Command, and his contentious relationship with other Air Ministry officers since 1937.

As the air battle developed between July and October 1940, four other reasons emerged. First, in the eyes of the Air Staff, Dowding showed poor leadership by failing to resolve the controversy between Leigh-Mallory and Park over the use of “Big Wings.” Second, as the Luftwaffe unveiled the night “Blitz” in September 1940, he appeared not to appreciate the need—widely shared by the Air Ministry, the Ministry of Aircraft Production, and politicians—for an urgent response.

Third, as 1940 was closing, the prime minister saw the RAF moving to an aggressive role, requiring a more dynamic leader for Fighter Command. Lastly, Churchill and Beaverbrook, Dowding’s two powerful political patrons throughout the daylight battle, came to believe that a new man was needed. Nonetheless, these seven explanations fail to erase the fact that from the end of 1940 Dowding was treated dishonorably by the senior commanders of the RAF.

Conspiracy Theories on the Sacking of Dowding

Was Dowding the victim of a vendetta? More specifically, did Leigh-Mallory and Bader collude behind the back of their C-in-C and use “political connections” to bring him down? Park believed in such a “conspiracy” and Dowding also felt that “dirty tricks” had been used by certain members of the Air Ministry. It could not have escaped Dowding’s attention that a guiding hand behind the ground swell of opposition was that of Sholto Douglas, deputy CAS.

The “conspiracy theorists” contend that the adjutant of Bader’s squadron, Flight Lieutenant Peter MacDonald, who was also a member of Parliament, was persuaded by Leigh-Mallory or Bader, or both, to meet the prime minister and expose the “Big Wing” controversy. In this version, Churchill followed up on the matter with speed, and plans were accelerated for the removal of Dowding and Park. On November 25, 1940, Douglas replaced Dowding and, on December 15, Leigh-Mallory took over from Park.

Was intrigue involved? A number of pressuring factors from both political and Air Service sources were seemingly operant. The fact that Douglas took the initiative and chaired the October meeting can be seen as a step taken toward his own advancement, since Dowding’s failure to resolve the tactical dilemma had left a leadership vacuum to fill. The agenda of the meeting reinforces the contention that the controversy over employing “Big Wings” in daylight battles was far from the sole reason for the subsequent changes being made in Fighter Command’s leadership.

When the meeting turned to night interception and Dowding’s bickering with Air Ministry policy since September 7, 1940, it became clear that Dowding was intransigent in complying with Douglas’s plan to form a night fighting wing with two Hurricane and two Defiant squadrons. Dowding believed that employing such a wing at night was dangerous, although he reluctantly agreed to the Air Ministry decision for a night-fighting wing. With Sholto Douglas as the “public prosecutor,” Dowding and Park were condemned while No. 12 Group and Leigh-Mallory were allowed to participate in the remaining battle on their own terms.

But the day also marked the emergence of Douglas, who thus far had been involved in the controversy only clandestinely by way of meeting minutes and via staff messages in the Air Ministry. Many historians contend that it was Douglas who applied pressure from behind the scenes, using Leigh-Mallory’s feud with both Park and Dowding as fodder for the controversy at the Air Ministry.

Some have argued that MacDonald’s intervention was likely made on his own initiative and not as part of a conspiracy instigated by Bader or Leigh-Mallory. Sir Denis Crowley-Milling, a pilot with No. 242 Squadron at the time, has stated categorically that “Douglas Bader, Leigh-Mallory and all of us were totally unaware of this approach [MacDonald’s to the PM].” Thus, it could be seen that Leigh-Mallory was accused unjustly of forming a plot to overthrow Dowding.

The Death of Leigh-Mallory

Leigh-Mallory remained an irritant. In 1944, shortly before the D-Day invasion of Normandy, the air marshal, whose responsibilities in the upcoming invasion included the Allies’ entire tactical air operations, vexed Eisenhower with the prediction of horrendous losses by the airborne and glider forces, and urged that the American parachute drops and glider landings behind Utah Beach be cancelled. Thankfully, Ike chose to ignore Leigh-Mallory’s advice and the airborne plan went ahead successfully as scheduled.

In August 1944, while heading to his new post as commander of air forces in South-East Asia, Leigh-Mallory died when the plane in which he was riding slammed into a mountain in the French Alps. By then an air chief marshal, he was the highest ranking British officer to be killed in World War II. Thus, Leigh-Mallory did not survive the war and he left no record to explain his policy during the Battle of Britain. Could Leigh-Mallory have been a “scapegoat,” thereby acquiring the damaged posthumous reputation as being the unwitting principal foil for Sholto Douglas’s sacking of Hugh Dowding?

Leigh-Mallory’s critics have presented him as uncooperative and scheming, placing him centrally in a plot to unseat Dowding and Park by using political influence. Park’s obituary referred to the conference of October 17, 1940, as being “instigated primarily by the AOC 12 Group.” Such opinions about Leigh-Mallory are, according to one historian, “unsupported by evidence and do injustice to his memory.”

Churchill’s Defense of Dowding

In 1942, Dowding retired officially from the RAF. The Air Ministry refused to honor him by promotion to marshal of the RAF, but Churchill saw to it that he was elevated to the peerage as Lord Dowding of Bentley Priory. He was asked to write an official report of the Battle of Britain, which was never published. Instead the Air Ministry wrote its own history, without even mentioning his name.

Churchill was infuriated by this. He wrote to the minister for air, Archibald Sinclair: “The jealousies and cliquism which have led to the committing of this offense are a discredit to the Air Ministry, and I do not think any other Service Department would have been guilty of such a piece of work. What would have been said if … the Admiralty had told the tale of Trafalgar and left Lord Nelson out of it?”

Totally agree about Lee Mallory and Douglas Badder who had a big Ego !

As regards Dowdings talking of his dead pilots the story fails to say that Dowding and his wife were Spiritualists ,she died before WW2.

During the first World War Dowding was instrumental in making ground to pilots in the Air Radio communications . As well as organising the Airfields, Group Controls, Radar Stations at the Coasts, the flight centre plotters with info of German plane numbers and Aircraft designation for R.A.F fighter pilots before they intercepted the enemy as to numbers ,height and direction all put together by Dowding before a Luftwaffe came over in 1940 . The UK should apologise to any surviving members of Dowdings Family and honour him with the highest R.A.F rank it denied Dowding when he retired in 1942.

Without Dowding and his system, it is Doubtful the Battle could have been won. By the time Mallorys Big wing was up, the enemy were withdrawing. The primary battle was defending Airfields, which was Mallory’s job.

Dowding and Park with the system and pilots Won the battle

Superb article, which further reinforces my view that a great disservice was done to a truly great man. The fact that Hugh Dowding didn’t have a statue built in his memory till so long after the war is further evidence, if any were needed, that a conspiracy existed to deprive him of his rightful place in history. Without Dowding we would have lost the Battle of Britain, ergo the Second World War. His importance as an effective and successful war leader can never be exaggerated. Only Churchill contributed more to Britain’s successful stand against the Nazis. Dowding deserves nothing but honour and respect as his due.

Unless I am mistaken, I remember a thing called the fire-bombing of Dresden which he supported and was horrible and probably unnecessary. That might tarnish his reputation.

But War is truly hell, and the victors usually are willing to take actions without consideration for losses (on either side). Unfortunately, an effective General or Admiral or CIC must be willing to take such actions. Another example is the atom bombs on Japan approved by the Commander In Chief!

You are mistaken about Dowding approving of Dresden, since it happened in 1945, long after Dowding had retired.

By the time the bombng of Dresden occured, Dowding was retired. Sir Arthur Harris was in charge and he was responsible for Dresden

Not surprising that Dowding’s name is being lost to history when the headlines in stories about him carry his name as “Downing.” Pay attention.

Churchill (who, ironically, contemporaneously approved Dowding getting the sack) was treated similarly at war’s end — handed his hat and shown the door, with far too little thanks for his invaluable service on his way out. There’s a lesson in there, somewhere.

The “lesson” is fairly well depicted by the Kipling poem, “Tommy”.

The 1969 movie “The Battle of Britain” which was my first introduction to Dowding and Leigh Mallory, and probably the most significant account of the event in the contemporary era, shows the truth. Dowding, played heroically by Laurence Olivier is inspiring and clearly the architect of the victory, as is Keith Park. Leigh Mallory comes across as the deluded fly in the ointment that he was.

One other thing to mention was the Bomber offensive. The independence of the RAF was dependent on the promise of strategic bombing. The air chief’s Dowding upset in the late 30s were of the ‘Bomber will always get through club’ their efforts against Germany in daytime amounted to huge losses for no gain in 1939 and in 1940 Dowding returned the compliment to the Luftwaffe.

The wind had been taken from the bomber baron’s sails. The most important sacking that autumn was Cyril Newall. He had become a skeptic of strategic bombing and was replaced by Peter Portal who was a strong advocate. The decision of factory space and finance for 1941 and 1942 was approaching and Churchill wanted an air offensive – all the RAF had to offer was inaccurate night bombing and fighter sweeps over France, and a generation of talent would be wasted reinforcing that failure.

No way Dowding or Park would have allowed Fighter Command to be wasted over France as Sholto-Douglas did. And when the Inskip report laid bare Bomber Command’s failure in late 1941, they would both have told them ‘told you so!’

They were sacrificed on the altar of the RAF founding myth.

Although I did not know my stepfather, Lord Dowding, until 1946, (when he was courting my mother, who he later married in September 1951), I’m probably the only person still alive who knew Dowding well.

There is a serious misinformation about the timeline of his interest in spiritual matters.

“To paraphrase David Fisher, “This was also a man whose mind broke from the strain at the height of the battle, who talked to the ghosts of his dead pilots, but who nevertheless was able to keep another part of his mind clear enough to continue making the daily life-and-death decisions that saved England” …

I don’t know where David E. Fisher, (a Professor of Geology at Miami University, USA) fished this inaccuracy from, (as also portrayed in the excellent video ‘Fighting the Blue’). Like so many pundits on the life of Hugh Dowding, Fisher never personally knew him or referred to his family for firsthand information.

Dowding during his long military career, and throughout the time that I knew him until his death at our home in February 1970, was a man of deep moral conscience. Following his retirement from the RAF in 1942, he had received many letters from bereaved families who had lost loved ones, many under his command.

(My mother was one of the many who wrote to Dowding, wondering if he could find out more details of the fate of the crew of the Lancaster bomber, in which her husband was the flight engineer, and had failed to return: https://www.airmen.dk/a014240-DW9.htm )

Dowding went to the Church for answers to the question, ‘What happens after one is dead? – but no satisfactory answer was forthcoming. For Dowding, this was not good enough for the memory of his airmen or the grieving families they left behind. So the wouldbe engineer (who with the shortening of the two-year course, due to the Boer War in South Africa, he failed his exams at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, for a commission with the Royal Engineers in 1900) began to investigate the possibility of an afterlife. He wrote four books on his investigations (which I have had republished, Many Mansions 1943, followed by Lychgate (1945), The Dark Star and God’s Magic. http://whitecrowbooks.com/books/page/many_mansions/ )

As an aside, Dowding was a keen sportsman, his passion skiing, which he preferred to flying.

In his youth Dowding was an accomplished skier, winner of the first ever National Slalom Championship, and president of the Ski Club of Great Britain from 1924 to 1925.

I hope Fisher’s unfounded remarks will be removed from this excellent account.

I once had the misfortune to meet Douglas Bader in the mid sixties at RAF Odiham. A more obnoxious, unpleasant and offensive individual I have yet to meet. His attitude towards the ground crew was appalling.

In stark contrast, Micky Martin (former 617 Squadron, Dambusters) AOC of 38 Group, also at Odiham, was an example of true leadership. Always ready to engage with cheerfulness and encouragement whatever the rank, he commanded respect and loyalty.

@ David Whiting: “Hear, Hear!”

I feel that Dowding was treated quite shamedly by the British Government, Shalto-Doughlas and Leigh-Mallory. Had Mallory’s “Big Wing” theory been implemented at the beginning of the Battle of Britain, the battle would have been lost. It was only Hugh Dowding’s foresight, tactical insight and willingness to adopt emerging technologies such as RDF along with the outstanding support he got from Keith Park (also not adequately recognised for his efforts during the Battle) that resulted in the Battle of Britain being won. Dowding and Park need more recognition for their efforts. Those that tried to undermine these men for their own selfish interests had nothing to do with the success of the RAF during the Battle of Britain.

Once again, two fine officers were crucified on the cross of internal RAF politics. Happens all over, sadly.