By Alan K. Lathrop

Visitors to a certain part of Rome today may not even be aware that they are walking in an area that came about because of an architectural vision of Benito Mussolini, Italy’s infamous fascist dictator.

Mussolini is best remembered today for aligning himself with Adolf Hitler and for his bombastic speeches, his military attacks on helpless countries—namely, Ethiopia and Albania—in a vainglorious effort to create a powerful empire reminiscent of ancient Rome, and for leading his country into military fiascos. He is less remembered, perhaps, for his public-works projects at home that were aimed at demonstrating to the world the capability of the fascists to improve the lives of the Italian people and showcase the glories of his regime.

Mussolini Seizes Power

After World War I, Mussolini, a newspaperman and a veteran, founded the Italian Fascist Party in 1919 in Milan. He emerged as a national leader once the fascists forcibly took over town councils in several of the largest cities, including Milan. This action became the basis of a mass movement that culminated in 1922 with the fascists becoming the dominant political force in Italy.

Following the fascists’ famous March on Rome on October 22, 1922, King Victor Emmanuel III was persuaded to appoint Mussolini prime minister to form a government out of the political and economic chaos that had descended on the country in the wake of the Great War. With his appointment, 39-year-old Mussolini became the youngest prime minister since Italian unification in the mid-19th century. Mussolini used the assassination of Giacomo Matteotti, a leading socialist and critic of the fascists, to form a one-party dictatorship two years later and styled himself “Il Duce” (the Leader).

Rebuilding Rome

Almost from the start of his regime, Mussolini developed an obsession with Rome and its history and gave it a special prominence in his plans to merge the cultures of the ancient past and the fascist present. Virtually everything between antiquity and the modern era was ignored or forgotten.

Mussolini initiated ambitious plans to turn Italy’s capital city into a grand and glorious mecca for visitors from around the globe and to rehabilitate its former dominance as the greatest city in the Western world. In Mussolini’s vision, the city would become the capital of a new fascist Roman Empire.

A giant reconstruction program for Rome called a regulatory plan was announced in 1926. Mussolini’s ideas for remodeling Rome may have been inspired in part by a combination of Pierre Charles L’Enfant’s plan of Washington, D.C., in the 1790s, and Georges-Eugène Hausmann’s rejuvenation scheme for Paris in the 1870s, combined with touches of the Neo-Classical-inspired City Beautiful movement of the early 20th century in Europe and the United States.

The first objective was to clear space around ancient sites to free them of surrounding urban clutter and reveal them in all their awe-inspiring grandeur. Second, the spaces thus created would permit the construction of new and wider thoroughfares to accommodate the increased volume of vehicle traffic. Third, new buildings and developments would be erected as monuments to Mussolini and fascism in accordance with modern tastes and yet recall the styles of ancient Rome.

The emphasis on architecture as a significant component of the new fascist culture gave Italian architects a plethora of design opportunities and kept pencils busy on drafting boards. Many designers hastened to align themselves with Mussolini’s regime in the hope of being given a chance to play a role in designing impressive buildings, public monuments, and the expositions that, in one way or another, celebrated fascism and the rise of Mussolini.

The Mostra Della Rivoluzione Fascista

The first exposition held to celebrate fascism was the Mostra della Rivoluzione Fascista (abbreviated either MRF, or MdR), which opened in Rome on October, 29, 1932, a decade after the March on Rome. The Fascist Party allocated 2.5 million lire toward its construction, and the MRF spectacularly showcased the rise of fascism and exalted the cult of Mussolini by clearly demonstrating how he had modernized the nation.

When finished, a sleek, modernist façade emerged that featured four giant fasci, a symbol of fascism borrowed from the ancient Roman Republic. A fasces consisted of a bundle of sticks or poles tied together with ribbon with an axe head protruding from the side of the bundle representing the power of law. The fasces was carried at the head of a procession of judges parading into court.

The giant fasci outside the MRF stood 30 meters high and were made of sheets of oxidized copper riveted together. The exhibit was a smashing success and drew millions of visitors from all parts of the country to gaze in admiration at the achievements of the Fascist Party and of Mussolini.

Mussolini’s Pact of Steel With Hitler

By 1935, plans were well under way for the rebuilding of Rome in fulfillment of its “fatal destiny” as the “ideal point of convergence” for the “synthesis and broadcast of human civilization,” as historian Eugene Anderson wrote more than 20 years later. At the same time, Mussolini was also planning his conquest of Ethiopia, whose capture would be the first step in Il Duce’s long-cherished dream of rebuilding the Roman Empire of antiquity and making the Mediterranean an Italian lake.

The massive costs of reconstructing Rome, building new towns for workers, and increasing the production of war materials placed an enormous strain on the Italian economy, which was already in dire straits as a result of a high valuation of the lire and Mussolini’s tight control of overseas trade that made it difficult for Italy to compete in foreign markets. The lower classes shouldered the burden of financing the state while the upper classes and landed elite continued to be favorably treated so that the Fascist Party would benefit from their support. Large estates were viewed as a means of controlling the peasants, and the industrialists acted as powerful friends and advisers to the government and as a force to command the workers.

As the world watched in horror, Mussolini’s mechanized army launched an invasion of Ethiopia in October 1935, crushing Emperor Haile Selassie’s much weaker and poorly equipped troops. Selassie appealed to the League of Nations for assistance, and in response the League declared Italy an aggressor and called for the imposition of sanctions.

Mussolini signed the Pact of Steel with Hitler in 1936 to create the Rome-Berlin Axis. For the next seven years, Italy was almost constantly at war.

Concurrently with the formation of the Pact of Steel, the Italians joined the Germans in sending military aid to support General Francisco Franco in the Spanish Civil War, which they viewed as a struggle against communism.

Esposizione Universale di Roma

Within a month after Mussolini launched his attack on Ethiopia, an idea emerged in the regime for holding a large and ambitious exposition, a world’s fair that would outshine all previous ones. A request was sent in November 1935 to the Bureau International des Expositions (BIE) to designate Italy as the host for a “First Category General Exposition” in 1941. Such expositions were held every six years, and this one would fall a year before the 20th anniversary of the fascist March on Rome. The regime hoped to regain the support of foreign nations that it lost when it invaded Ethiopia. The following March, Il Duce declared the founding of the new Italian Empire and on June 25, the BIE granted Italy’s request.

“E 42,” as it came to be called, an abbreviation for “Exposition 1942,” was first designated as the “Exposition of 1941-42” and then, in 1937, became the “Exposition of 1942.” The theme was officially the Olimpiade delle Civilta—the Olympics of Civilization––to be held in a huge new building complex, the Esposizione Universale di Roma or EUR, which would be constructed on the southern fringes of Rome between the capital and the ancient port of Ostia. The 1944 Olympic Games had also been awarded to Italy and were scheduled to take place in the EUR, but war overtook Europe long before they could be held.

Final plans for the EUR were drawn up by 1938, and construction began in 1939. The construction of the EUR had several overarching goals: first, to convince outsiders that Italy was a peaceful nation as demonstrated by its spending enormous sums on a project with peaceful intent; second, that Mussolini and his fascist regime held the power balance in a New Europe between Germany, Britain, and France; and, third, that an international system of industrial corporations such as Mussolini was trying to erect was a “middle road” between communism’s destruction of world order and capitalism’s decline in the grip of a worldwide economic depression. One will notice that the goals, taken together, sought to emphasize an Italian role as simultaneously peace negotiator and power broker in Europe and the world beyond.

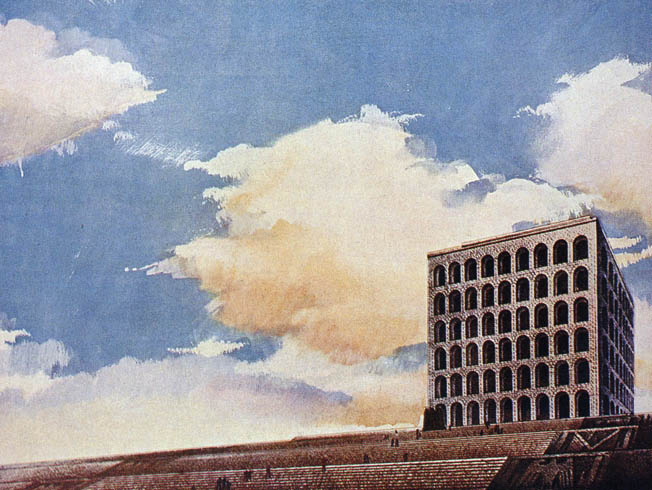

In 1939, the government issued an impressive book that laid out the extravagant plans for the EUR. It was beautifully illustrated with watercolor architectural perspectives of the finished project and a narrative description of the layout and component parts. A 400-hectare site (roughly 988 acres), known as the Tre Fontane (Three Fountains), was chosen south of Rome along a highway already finished in 1928 called the Via del Mare (Road to the Sea). Today the Via del Mare is rated as Italy’s most dangerous road, with some 250 deaths recorded between 1996 and 2005, most probably attributable to speed. Together with an adjacent rail line, the highway would connect Rome to Ostia, thus symbolically linking modernity with antiquity and a brilliant future with a brilliant past.

The site chosen for EUR was an empty area on which nothing had been built in modern times. A fifth of the envisioned buildings were to be permanent, consisting mainly of office structures and museums, plus such decorative motifs as gardens, fountains, and waterfalls. The site would be maintained and developed for shopping, residential, cultural, and other uses, unlike previous world’s fairs such as Chicago (1933), Barcelona (1929), Brussels (1935), and Paris (1937)—all of which were demolished after they closed, leaving only one or two permanent buildings.

All of the structures erected by foreign nations, however, would be temporary and removed after E 42 ended. EUR would thus be a new city, similar to others planned throughout Italy, again showcasing fascist power, culture, determination, and prestige.

Grand Designs of the EUR

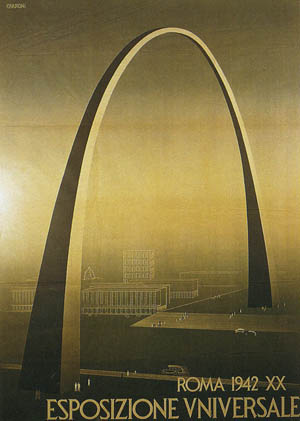

A dominating feature of the EUR was to have been a huge arch spanning the main south entrance into the grounds and mirrored in a large man-made lake. It was designed by architect Adalberto Libera, who also had won the competition for the design of the Palace of Congresses. The arch was never built because it was beyond the capabilities of construction technology of the time. The artificial lake, which still exists, was a key feature of the grounds where the public could find opportunities for recreational exercise and athletes could swim and participate in competitive events, including the Olympics.

The layout of EUR was on a scale to match its architecture, stressing monumentality, axiality, and balance. A modernist aspect of the exposition was to take the form of main thoroughfares ending in awe-inspiring vistas constructed on a grid and sufficiently wide to accommodate a high volume of vehicle traffic, both private automobiles as well as buses.

At Mussolini’s insistence, the streets were to be lined with apartment and office buildings built of glass and steel, but none of these strikingly futuristic structures were completed before war broke out—not because they were considered too daring in their architecture, but because shortages of glass and steel brought on by wartime demands forced them to be abandoned in favor of locally available marble, concrete, and masonry.

What was erected were designs that, instead of descending into stodginess because of their traditional materials, brilliantly embraced “the best of the old methods of construction without producing sterile imitations of antique structures,” historian Diane Ghirardo has written.

World War II Destroys the EUR

Ground was broken for the EUR in 1938 and continued through the six-month Phony War of 1939-1940. Real war was soon to intervene and halt its completion. On September 1, 1939, Hitler launched his attack on Poland. He declared war two days later on Great Britain and France. Italy had already continued its military ambitions by invading Albania in April 1939, and then simultaneously declaring war on the United Kingdom and France on June 10, 1940.

The Italians overran British Somaliland by August 19, then turned their attention to Egypt. The Italian Army in Libya, under Marshal Rodolfo Graziani, pushed the relatively tiny British forces back to the border, then eventually retreated, losing men and war materiel until being rescued by Erwin Rommel. In October 1940 Mussolini launched his invasion of Greece, another Italian military fiasco requiring rescue by the Germans.

By 1942, Mussolini’s efforts to create an empire and turn the Mediterranean Sea into an Italian lake were in tatters, his military dreams in shreds. He was now a second-rate political and military leader, the butt of jokes, and forced to exist under the shadow of Hitler. The unsuccessful campaigns had effectively put an end to hopes of completing the splendid EUR, hosting throngs of awe-inspired visitors to a reconstructed Rome, and holding the 1944 Olympic games in Italy.

After the Germans were driven out of Rome in June 1944, the Allies occupied the EUR and, after they moved on, the buildings were filled with hordes of civilian refugees who poured into the area from destroyed cities and to escape German brutality. The refugees tore the buildings apart for firewood, and gangs carried away everything else. The buildings were left stripped and deserted for five years, and virtually forgotten.

The EUR Today

In February 1951, the Italian government announced a program to repair the wartime damage to the EUR and to complete its construction. It was carried out under the direction of architect Virgilio Testa, who restored the damaged buildings and finished constructing those that had not been started or were only partially completed.

Today, the EUR is a thriving upscale residential and shopping suburb, with government offices and several museums also located there. Among the museums are the Museo della Civiltá Romana (Museum of Roman Civilization); the Museo delle Arti e Tradizioni Popolari (the Folk Museum); the Museo Preistorico Etnografico L. Pigorini (Museum of Ethnography and Prehistory); and the Museo dell’Alto Medioevo (Museum of the Middle Ages).

Mussolini’s bellicose image vastly overshadows his reputation as a promoter of architectural and engineering projects in Italy. Yet, it was the latter in which he had his greatest successes. His political stature suffered as military defeats increased and he lost the support of the Italian people. However, his efforts to modernize Rome, to promote the culture and history of Italy, to develop better living conditions by building some 19 new towns throughout the country, and to construct an efficient, viable transportation and communication network were, in the main, successful.

Undoubtedly, most of these would have been realized had his policies in Italy and abroad not been undermined by a belligerent foreign policy that cost his regime important friends and allies. This was followed by a disastrous war of his own creation that bled away irreplaceable resources and energy that could have been much better expended on infrastructure improvements at home.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments