By Mason B. Webb

The very nature of war means that some participants will be killed and others will be wounded, and some estimate the deaths in WWII to be around 85 million. While battlefield medics and the surgical teams who care for the wounded have been hailed as unsung heroes, and books and articles have been written about them, very little has been said about the men of the U.S. Army Quartermaster Branch’s Graves Registration units who were responsible for so many WWII casualties.

Since the dawn of warfare, the problem of what to do with dead bodies littering a battlefield has been an uncomfortable question for commanders. While it is unpleasant to think about violent death and the decomposition process, it is a reality that must be faced by all who go to war—and their families.

Ancient armies simply stripped the dead of their armor and weapons and allowed the natural processes to reclaim the physical remains; graves and tombs were, for the most part, reserved for kings, emperors, generals, and the wealthy nobility. As the common ancient soldier usually carried no means of identification, burial, if there was burial, was in a shallow, common mass grave. At other times, bodies might be piled up and a funeral pyre lit.

Accounts have been written by soldiers at Waterloo, Gettysburg, and the Somme describing the unforgettable stench of hundreds of decomposing corpses on the battlefield; the liberators of Nazi concentration camps, too, have vividly written about the overwhelming, permeating, sickly-sweet stench of mass death, so disposing of the dead has become a priority.

As the centuries passed, what to do with the remains of dead soldiers became more formalized. For those killed on foreign battlefields, a more-or-less swift burial was the norm; bringing the dead home for burial, a process that could take weeks before the advent of airplanes, was not an option.

Also, before the introduction of M1940 identification tags, the so-called “dog tags” of World War II, and the more recent science of DNA, being able to identify a particular dead soldier was a haphazard affair. Before going into battle, Civil War soldiers sometimes wrote their names and the names of their next of kin on a scrap of paper that they put in a pocket or pinned to their uniforms.

In his book, Soldier Dead: How We Recover, Identify, Bury, and Honor Our Military Fallen, author Michael Sledge writes, “Only those closest to the dead and to the combat situation will make the choice to risk bringing back the bodies of the dead, as it is an intensely personal decision.”

For the American military, the past century has put more emphasis on retrieving the bodies of the fallen, even when retrieving the fallen puts others at risk. And who can forget the scene in The Longest Day, when John Wayne, playing battalion commander Lt. Col. Ben Vandervoort, looks up at paratroopers who became WWII casualties, hanging from trees at Ste. Mere Eglise, and orders, “Down! Get them down!”

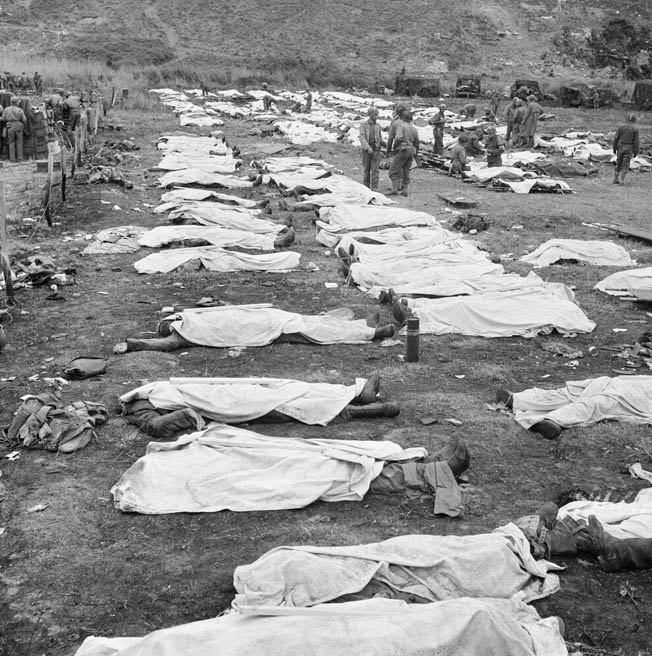

Graves Registration Service (GRS) teams were deployed to land shortly after the first wave of amphibious troops hit the beaches to remove WWII casualties from view, as it was felt that subsequent reinforcements, for morale purposes, should be spared the sight of dead comrades. Except for perhaps a few soldiers who had previously been employed in a morgue or funeral home, the handling of corpses, especially of those who had died a bloody and violent death, was a new and unpleasant assignment for GRS troops.

Blosville Cemetery in Normandy Was Originally Intended to Temporarily Serve WWII Casualties from the 82nd Airborne

During the Normandy invasion, Sergeant Elbert E. Legg, a member of the 4th Platoon, 603rd Quartermaster Graves Registration Company, attached to the U.S. VII Corps, volunteered to arrive in one of the 82nd Airborne Division gliders at Landing Zone “W” on D-Day to quickly establish a Graves Registration collection point because, as he said, “The schedule called for the Graves Registration unit and its vehicles to arrive on the beach about D+3. This would be too long for mass casualties to go unprocessed on the battlefield. Estimates of battle dead for establishing the beachhead ran as high as 10,000 American soldiers.”

After coming in by glider on the afternoon of June 6, 1944, Legg set up a temporary cemetery in a pasture bordered by hedgerows. He recalled that the first temporary cemetery was established near the village of Blosville, about three miles south of Ste. Mere Eglise, “an area with crashed gliders strewn everywhere and hundreds of parachutes hanging from hedges, trees, and houses.” The Blosville Cemetery was one of six American cemeteries established in a radius of about 20 miles.

At the outset, Legg noted, the Blosville Cemetery was intended to be temporary and primarily serve the 82nd Airborne Division. Shortly thereafter, jeeps began arriving with dead soldiers; the drivers stood back, not wanting to become involved. Legg, too, recalled his initial squeamishness: “For the first time in my life, I touched a dead man. I grabbed the leg of one of the bodies and it rolled onto the ground. As I struggled, the drivers gave in and assisted me with the remainder of the bodies. There were now 14 dead lying in a row and more loaded vehicles were driving into the field.”

Recruiting Labor For the Task

A Lieutenant Fraim, the Graves Registration officer for the 82nd, introduced himself to Legg and told him to establish a temporary cemetery in the area while he went into Blosville to draft volunteer civilian labor to dig the graves. Legg said, “When asked how he would pay the workers, he displayed a musette bag full of invasion French francs intended for that purpose.”

Legg returned to the pasture and stuck his heel in the ground. “This would be the upper left corner of the first grave. I found an empty K-ration carton and split it into wooden stakes. I paced off the graves in rows of 20 and marked them with the stakes. I had no transit, tape measure, shovels, picks, or any other equipment needed to establish a properly laid out cemetery. I also lacked burial bags [mattress covers], grave registration forms, and personal effects bags. The situation rapidly exceeded what had originally been planned for the one-man Graves Registration unit, and this was still the first day.

“Lieutenant Fraim returned and said he had arranged for about 35 Frenchmen to start digging graves the next morning. By this time about 50 bodies awaited burial. I found an abandoned foxhole in the middle of an orchard and set up housekeeping. Sleep came easily as the fatigue of the day’s events had begun to take its toll.”

The next morning Legg saw a column of Frenchmen coming his way down the road, “carrying a mixture of picks and shovels and lunch pails. All the men were very old or crippled in some way. It took little time to assign them to digging graves. There was little conversation since I spoke no French and they spoke no English. The long row of bodies and marking stakes made it apparent what was to be done.” All 50 bodies were buried that day, with more arriving all the time.

“About 1600 hours on D+1, Lieutenant Fraim came by to inform me that I should stop work and move with the other troops located around Les Forges crossroads to a safer location. The Frenchmen were paid and instructed to return when they again saw activity around the cemetery. All graves were closed and a military chaplain came to conduct an all-faith burial service. I … headed for a group of vehicles forming near the crossroads.”

Processing Hundreds of WWII Casualties

The next day Legg returned to the cemetery near Blosville where he found the French labor detail waiting to be told what to do. He said, “During the previous night, a sharp firefight had taken place around the crossroads and apple orchard area. Battle debris was everywhere, including German helmets, weapons, and gas masks. The cemetery area had not been disturbed. This was D+2 and the bodies were piling up, including about 25 enemy dead. Lieutenant Fraim arrived in mid-afternoon and said he would look for more laborers for the next day. He indicated he would also check to see if he could get German prisoners-of-war to assist with the digging.

“A few more bodies were interred on D+2, and several more rows of graves were marked off. The laborers were encouraged to return early the next day and to bring their friends. Before they left, I had them dig a slit trench near the hedgerow at the corner of the cemetery. This was covered by a tent shelter-half and would serve as my home for Graves Registration activities during the coming days.”

Over the course of the next week, Legg was extremely busy. By D+3, he said, “Bodies above ground now numbered in the hundreds, with about half being German. About 70 Frenchmen arrived and dug over a hundred graves. I was pressed to do even rudimentary processing of the bodies.”

At the Blosville Cemetery, a Quartermaster Service Platoon with vehicles, pick axes, and shovels arrived. “About 150 German prisoners of war also arrived and were assigned digging duties,” Legg said. “Activity was picking up. The big limitation was processing bodies to insure proper identification and security of personal effects. A second plot of 200 gravesites was marked off to provide work space for all the diggers. French laborers were now handling and moving all bodies.

“This level of activity continued until D+7 when a portion of my unit, the 4th Platoon, 603rd Quartermaster Graves Registration Company, arrived and took over the operation of the cemetery. They found much of the work had to be done over, including relocation of all bodies. About 350 Americans and 100 Germans were underground by this time. Several hundred Germans awaited burial, but the backlog of American dead was less than 100.”

6,000 Graves

Legg noted that weapons, ammunition, and equipment that had once belonged to the deceased were piling up at the cemetery. “Most bodies arrived fully clothed and with web gear,” he recalled. “Some had gas masks and small-arms weapons, and nearly all had some sort of ammunition and rations. All usable government equipment was taken from the bodies. Initially, all government-issue equipment was thrown into a big pile and made available to anyone who wanted it. When the 4th Platoon arrived to take over the cemetery, personnel were assigned to sort the equipment and secure the ammunition. The French laborers watched longingly as most American bodies were buried with their jump boots. Later they were allowed to take the heavy leather boots from some of the German dead.”

By the time Operation Cobra, the St. Lô breakout, took place and Allied forces moved east into central France, this cemetery contained over 6,000 Allied graves. They were later disinterred and reburied at the huge American Military Cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer, atop the bluff overlooking Omaha Beach. Today a small monument at the Les Forges crossroads marks the location of the Blosville Cemetery.

Recovering the Dead

As procedures for collecting the combat WWII casualties evolved, it became the responsibility, whenever possible, of the frontline infantry and/or medics to retrieve their fallen comrades and evacuate them through battalion and regimental areas to the division collection point, where GRS men were standing by for the next step in the processing operation; in some cases, it was GRS personnel who were also tasked with the retrieval.

Retrieving battlefield remains proved to be extremely problematic in some theaters of operation. A Quartermaster Branch report noted that problems of Graves Registration services in the Pacific area were more complex than in Europe due to the extended area over which fighting took place. “In New Guinea, for example,” the report said, “consolidation of cemeteries has become necessary, due to the fact that group burials took place at widely scattered points and temporary battlefield cemeteries were established close to the actual combat area. Isolated graves were marked with improvised crosses fifteen feet high in order to permit future identification.

“The nature of the country in New Guinea, however, has proven an obstacle to search teams. Isolated graves are sometimes located far in the mountainous interior, and overland transportation, confined to native trails, is slow and difficult. Some New Guinea natives refuse to disinter bodies, and this means that at times the actual digging must be done by limited Graves Registration personnel. The task of locating isolated graves is sometimes complicated by the rapid growth of vegetation, the tall kunsi grass in some areas, and the dense jungle undergrowth in others.

“Confronting Graves Registration Service units in New Guinea is also the arduous task of recovering bodies from air crashes. Expeditions have been sent out from all bases to locate crashed aircraft and transport the bodies back for burial in military cemeteries. These expeditions into the densely forested, mountainous interior of the country sometimes cover great distances and must be accomplished on foot with the aid of native carriers. Steep native trails winding over mountain peaks are the only means of access to this country, parts of which have seldom been traversed by white men.”

Retracing the Bataan Death March

Even after the fighting was long concluded, challenges remained. According to the Quartermaster Corps’ official history of the Graves Registration Service, in May 1945 the Army’s 601st Graves Registration Company undertook its most difficult assignment when it began retracing the route of the infamous Bataan Death March to recover and identify the remains of Americans who died during that journey.

From Mariveles, a town at the southern tip of Bataan, Highway No. 3 stretches northward through the towns of Balanga, Orani, and Bacolor, and runs 120 miles north to the town of San Fernando, where the six-day march ended. All along this route lay the bodies of Americans, English, Dutch, and Filipinos, unclaimed and unidentified after nearly four years of war. With the capitulation of the Japanese on Bataan early in the spring of 1945, the Army set to work to track down all information that might lead to the identification and proper burial of the remains of Bataan’s heroic defenders.

Army officials decided that the task might be simplified if an actual participant of the Death March could be found, a man who knew the route, the names of some of the victims, and the places where men had fallen. The only person still in the Philippines at that time who had participated in the march was Master Sergeant Abie Abraham, released from Cabanatuan Prison by the 6th Rangers in January. At the personal request of General Douglas MacArthur, Abraham, a 19-year Army veteran, consented to help the 601st in its efforts.

The problems faced by the Army were many. There were no official Army records of either the men on the march or the men who had died at the hands of the Japanese. Men of the 601st had no idea what three years of tropic rains and rapid growth of vegetation could do to hastily-dug graves. Also, there remained the greatest problem of all—proper identification of bodies.

Identifying a Fallen Soldier

Because of the lack of official information, Graves Registration officials turned to Filipino civilians for aid. The first platoon of the 601st, under the command of Lieutenant Manuel Nieves, contacted civilians in the town of Balanga, about halfway up from Mariveles, the starting point. Public officials of the town were asked to announce to the townspeople that any information they might possess would be of great value. At Sunday church services priests asked their congregations for cooperation.

A public meeting was held in the square of Balanga, and Sergeant Abraham was introduced as a survivor of the Death March. He told of seeing some of his comrades die when the weary, tortured marchers reached the town, and questioned the natives as to the disposition of the bodies.

At this point, Mario Bugay, a resident of the barrio, said that he had seen a burial take place near his home. Upon questioning it was learned that the man had not died on the march itself but had been killed a few months later while on a work detail in Balanga.

Bugay was asked how the man buried there was killed. “He was very weak at that time,” Bugay replied. “The Japanese called for him but he could not move, so the guard clubbed him to death. He was buried by his comrades.”

Bugay went on to describe the man as about 5 feet 11 inches tall, quite thin and pale. Another Filipino, Alfredo Pardillo, stated that he knew the name of the American soldier from an epitaph on the grave. Questioned as to how he could remember the name for such a long period of time, Pardillo answered, “I can remember the name, sir, because I have read it here during unforgettable times.”

When the body was found and disinterred, evidence of a fracture on the left side of the skull was discovered, substantiating Bugay’s story. It was also possible to make a dental chart to establish identity by checking against War Department files.

Conflicting Witnesses

Unfortunately, not all recoveries were so easily accomplished. Six months after the job was started, very few bodies had been positively identified.

In all towns where meetings were held, Sergeant Abraham was introduced and did his best to search the natives’ fading memories for information. At first the Filipinos were reluctant to assemble, remembering the meetings held by the Japanese at which machine guns and rifle butts exercised persuasion. American understanding and kindness soon won their confidence, however, and the numbers of volunteers gradually increased.

As the weeks went by and clues began to lead to conclusions, it became apparent that, although many individual graves and common graves amounting to small cemeteries could be found, this was merely the beginning of the process. Many more complicating factors arose. In some cases, after the passage of the Death March, entire towns were driven into the hills by the Japanese, and in the void that was left, no one remained to care for remaining WWII casualties. Swollen streams and tropical rains washed away many of the shallow, makeshift graves and, in some instances, scavenger animals had taken their toll.

Although fearing detection and retribution by the Japanese, brave Filipinos sometimes carried bodies hundreds of yards from the road, burying them in swampy land or rice paddies, and causing conflicting stories to arise. Witnesses to any event will always have slightly different versions, and in this case varying evidence on the location of graves had to be taken into account and investigated.

“Approaching San Fernando, Casualties Were Naturally the Heaviest”

The Filipinos’ love for trinkets became another barrier to success. From many talks with the natives along the route, it was evident that they had come into possession of many souvenirs, such as officers’ bars, NCO stripes, unit insignia, and identification tags. These “souvenirs,’’ either given to them by American soldiers or taken from the bodies of the dead, became naturally final and absolute identification factors of some of the dead.

Some of these had long ago been lost by the Filipinos, and some had become such prized possessions that their owners were reluctant to part with them. Graves Registration officials promised the natives that they would not be deprived of their souvenirs; the Army merely wished to examine them for possible evidence.

As each grave was found it was marked with a white cross, and detailed, scaled maps were made of the grave location. At one point near Bacolor, a few miles south of San Fernando, a white cross stood in a ditch by the roadway. A little farther south, about a hundred yards from the highway in a wet, marshy field, the graves of 20 unidentified dead were marked and staked off. The 601st had orders to disinter for proper burial only identified bodies so, while work toward that end continued, the dead lay in their initial resting places.

Sergeant Abraham noted, “Approaching San Fernando, casualties were naturally the heaviest. By this time, after nearly six days of marching, we were all about done for, and the Japs didn’t hesitate to use their rifles and bayonets on stragglers. I was in good condition from my days as boxing coach of the 31st Division, so I managed to make it.”

Disregarding all danger, and despite their many casualties during two years of battle in the Pacific, the officers and men of the 601st Graves Registration Company were a well-seasoned group with very high morale and a strong focus to find every American lost during the Death March. But even today, some 70 years later, not all of the dead have been accounted for.

“Unknown”

According to Army Field Manual 10-63 (“Graves Registration,” 1945, which superceded FM-630, 1941), one Graves Registration company was assigned to each corps having at least three divisions. Given the size of command they were expected to service, the GRS companies were, during large engagements, chronically understaffed and overworked.

Once WWII casualties had been brought to the collection point, a medical examination was made to establish the cause and certainty of death, and attempts at identification were conducted if the deceased had not otherwise been identified. In most cases the dog tags provided sufficient information but, when the tags were missing, the deceased soldier’s pockets were searched for other evidence, such as a letter from home or a photo of a wife or girlfriend. In some cases, a note written by the dead soldier’s superior or comrades before the body was evacuated provided the needed information. Sometimes a distinguishing feature, such as a birthmark or tattoo, or even laundry marks on clothing and serial numbers on watches, helped in the identification process.

Using these identifiers, the body would be placed in a mattress cover, blanket, or shelter-half fastened with large safety pins and buried in a temporary cemetery with a grave marker (usually a wooden cross or marker with a Star of David) bearing the identity of the deceased. At the time of burial, if a deceased soldier had both of his dog tags, one was left on the body and the other was affixed to the grave marker. Whenever possible, a chaplain of the same faith as the deceased performed the burial rites.

In too many instances, however, a soldier’s identity could not be discerned (perhaps because of being too badly mangled, fragmented, burned, or intermixed with other remains) and his grave would be simply marked “Unknown.” Identifying a group of victims, say, of an airplane crash or a crew incinerated inside a tank was always problematic, and every effort such as examining fingerprints and dental records was exhausted before declaring the dead “Unknown.”

Once the victim was identified, the War Department was notified by the field command and a telegram was dispatched to the deceased’s next of kin that began, “The Secretary of War desires me to express his deep regret that your son [husband, father, etc.] has been reported killed in action….” This was usually followed by a personal letter of condolence from the deceased’s unit commander.

After the deceased’s commanding officer had a chance to examine the fallen soldier’s personal effects to ensure that no items that would cause embarrassment or additional heartache for the next of kin (such as pornography or letters from, or photographs of, a mistress), the effects were sealed in a personal effects bag and shipped first to the Army Effects Bureau at the Kansas City Quartermaster Depot in Kansas City, Missouri. Great care was taken to ensure that the personal effects bags were not stolen or pilfered.

There the effects were carefully inventoried, soiled garments laundered, any government-issue articles removed, foreign money (except for souvenir money) converted to U.S. currency, and any cash or negotiable checks deposited in a bank to the credit of the next of kin. The property was then packed for storage pending receipt by the Effects Bureau of a shipping order. Only after all this was done were the effects sent to the next of kin.

In addition to taking charge of bodies retrieved from the battlefield, GRS units were also involved in taking care of the remains of service personnel who died in field hospitals of combat- or non-combat-related causes.

A Moving Battlefield

As was often the case on the fast-moving battlefields of World War II, Americans frequently came across enemy, Allied, and civilian dead. In these cases, too, GRS personnel were given the responsibility of identifying, whenever possible, the names of the dead and placing them in well-marked temporary graves (the U.S. government compensated land owners whose fields were used as temporary cemeteries); the GRS units had, as part of their personnel roster, draftsmen whose duty it was to draw accurate maps of all the graves. Field Manual 10-63 specifies that GRS companies were “not authorized nor equipped to perform embalming.”

On occasion, GRS personnel found themselves in danger from the battle still going on around them. Enemy snipers were as fond of picking off noncombatant medics and GRS men as they were shooting at fighting men. And, as FM 10-63 warns, “In the search for bodies, great care should be used to avoid booby traps and anti-personnel mines that may have been placed under bodies by enemy forces.”

Personnel who died at sea, if it were not practical to return them to land, were “buried” at sea in weighted mattress covers; the latitude and longitude of the burial locations were then reported to high authority.

The Graves at Malmedy

In 1997, Major Scott T. Glass, then commander of the Forward Support Company, U.S. Army Southern European Task Force, Lion Brigade, Vicenza, Italy, wrote a report on Graves Registration activities as they concerned the SS massacre of American POWs near Malmedy, Belgium.

As is well known, on December 17, 1944, an armored Kampfgruppe from the 1st SS Panzer Division, commanded by SS Colonel Joachim Peiper, encountered the U.S. Army’s Battery B, 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion on the road at Baugnez. After a brief fight, the woefully outgunned Americans surrendered to the Germans. Under orders to show no mercy, even to prisoners of war, Peiper’s men herded the Yanks into a snow-covered field and opened fire on the unarmed captives, killing 80 in a matter of minutes.

Some of the Americans played dead in the snow while a handful of others managed to escape into the nearby woods or took shelter in buildings but were soon flushed out and shot. Before World War I, the Malmedy area had been part of Germany. Local families had contributed sons to the German Army in World War II. In fact, local residents had pointed out to German troops the hiding places of some American soldiers attempting to escape the massacre. Once the killing was over, Peiper’s column moved on to other objectives.

Late that afternoon, American commanders heard rumors of a massacre of POWs near Malmedy. Recovery of the remains to confirm what had happened and also to gather and preserve evidence for a possible war crimes investigation became primary goals. However, it was not until January 13, 1945, almost a month after the slaughter, that American units recaptured and secured the Baugnez area.

The U.S. First Army headquarters selected a unit for recovery operations and deployed an Inspector General (IG) team to exercise overall control of the remains collection mission. The 3060th Quartermaster Graves Registration Service Company’s 4th Platoon drew the assignment of recovering, processing, and identifying the bodies.

The platoon arrived in the Malmedy area and entered the massacre site on January 13. Fortunately, snow had fallen several times since the massacre and a fresh layer covered the bodies. Temperatures had hovered below freezing, and the Germans had made no attempt to bury the bodies. These factors combined to keep the remains remarkably preserved.

The 3060th personnel conferred with the IG team, physicians, and representatives of the 291st Engineer Battalion before establishing recovery operations procedures. Operations began at the massacre field on January 14, 1945, and ended late the next day.

72 Bodies Found

Throughout the operation, the recovery field remained a frontline combat area. American infantry units had dug foxholes across a corner of the field, and German artillery observers could see the activity around the crossroads area. On several occasions, incoming German artillery fire forced temporary suspension of the work. In some cases, the shelling mangled some of the remains, complicating recovery and identification.

Heavy snowfall, enemy shelling, and a lack of available eyewitnesses to the atrocity prevented the Graves Registration soldiers from conducting thorough, systematic searches to locate all of the widely scattered remains. Still, over the next four months, the surrounding area yielded an additional 12 sets of remains, all of which were later identified.

Location of individual remains required assistance from a platoon of the 291st Engineer Battalion, which used mine detectors to locate the bodies from the metal of gear or personal effects. When mine detectors located a set of remains, soldiers used brooms to sweep away the snow covering the bodies.

Graves Registration personnel assigned each set of remains a two-digit number. A total of 72 bodies were found at the massacre site. Two Signal Corps combat cameramen photographed the initial location and general condition of each body. After the photographs had been taken, GRS personnel removed each body to a nearby road. In addition to being frozen, most bodies had also adhered firmly to the ground and, in some cases, to other remains. After separating remains from the ground and each other, a careful search under the bodies yielded more personal effects. These effects, if any were found, accompanied the body as soldiers removed it from the field on an ordinary stretcher. Workers removed neither equipment nor personal effects from any remains during the recovery process.

Litter teams from the 3200th Quartermaster Service Company and the 291st Engineer Battalion carried the remains several hundred meters along a road leading to Malmedy to a point secure from German observation. There the teams loaded the remains onto trucks for the short trip to the processing site.

Processing the Malmedy Dead

The 3060th set up processing operations in an abandoned railway building in Malmedy. The building had bomb and artillery damage to its roof and walls and had no running water and no electricity to permit night operations. However, it was the best available facility that combined space, proximity to the recovery site, security, and access to operation support. Processing operations ceased at nightfall.

Other advantages of the railway building included a tile floor for laying out the remains and the building’s relative obscurity, which sheltered it from public view. The temperature inside stayed a little above freezing, and workers had to set up several coal-burning drums to provide some heat.

Upon entering the railway station, 3060th Quartermaster Company workers placed the remains on the tile floor and then moved them to tables for processing. They then removed any bulky, outer winter garments that would impede examination of body wounds. Processing included searching these garments for personal effects that might assist with identification. These personal items would prove valuable later.

The 3060th soldiers filled out emergency medical tags, collected and secured personal effects such as pens, letters, watches, and wallets. Processing included a preliminary identification. Usually a single identification tag around the neck of a deceased could establish identity sufficiently.

If processors did not find a tag around the neck of the victim and instead found a tag somewhere else such as in a pocket, a search of other personal effects was required to establish identity. Common practice for laundry marking at that time required American soldiers to mark the last four numbers of their Army service number on their clothing. This provided another way to check the identity of Malmedy victims.

Fingerprints also helped establish identity. In some cases, processors used hypodermic needles to inject water in the remains’ digits to firm and fill out fingertips to allow a quality fingerprint. Almost none of the Quartermaster soldiers who were processing remains had received formal mortuary training before deploying to Europe, although a considerable number had already seen combat and the resulting human wreckage. This skill was one that had been specifically identified as critical and taught to new soldiers of the 3060th in France.

The 3060th Quartermaster Company soldiers lacked rubber gloves, aprons, and other similar gear to insulate them from thawed ice, blood, and bodily fluids. The standard-issue leather, cold weather gloves provided a poor substitute, becoming thoroughly soaked quickly. To solve this problem, workers discarded pairs of gloves after one or two sets of remains, but this created a severe demand for a scarce supply item.

Autopsies Reveal the War Crimes at Malmedy

Shortly after initial processing, three U.S. Army Medical Corps physicians, under close observation by the First Army IG team, performed autopsies on each set of remains. The autopsy team in nearly every instance used the two-digit number assigned in the massacre field to track and record the procedures. It was still possible that the massacre survivors could have been mistaken and the dead soldiers had died as a result of combat injuries. First Army headquarters meant to specifically determine if death had resulted from combat action or shooting after capture.

A survey of the 72 autopsies and photographs of remains on file indicate at least 20 had potentially fatal gunshot wounds to the head inflicted at very close range, in addition to wounds from automatic weapons. Most head wounds showed powder burns on the skin. An additional 20 showed evidence of small caliber gunshot wounds to the head without powder burn residue. Another 10 had fatal crushing or blunt trauma injuries, most likely from a German rifle butt. This easily confirmed suspicions that a serious atrocity actually did occur.

Only a couple of the personal effects registers or autopsy records mention the remains having identification tags. As thorough as the effects search and autopsy records are, it can be assumed that the massacred soldiers were not wearing their identification tags at the time of death. Why the soldiers in the Malmedy massacre did not have their identification tags on is not known.

This made recovery of personal effects associated with each set of remains critical to identification. Effects most valuable for identification purposes included pay books, wallets, rank insignia, small Bibles and religious tracts, rings, watches, and personal letters found on or under the remains. Despite the almost complete absence of identification tags worn on the remains, 3060th Quartermaster soldiers identified all the remains with 100 percent certainty.

After processing, identification, and autopsy, each set of remains received a tagged mattress cover as a burial shroud. Several times daily during the recovery operation trucks evacuated the processed remains to a temporary U.S. military cemetery at Henri-Chappelle, Belgium, about 25 miles north of Malmedy, that served units operating in the area. Today it is a permanent American military cemetery holding some 8,000 remains.

America’s Permanent Military Cemeteries

After the war, beautifully landscaped, permanent American military cemeteries were established on land generously donated by the liberated countries, and all of the bodies buried in the temporary cemeteries were re-interred in the permanent sites; the temporary cemeteries were then closed.

Each cemetery has been granted use of the site in perpetuity by the host government to the United States, tax and rent free. All of the American cemeteries in foreign lands are under the jurisdiction of and maintained by the American Battle Monuments Commission, headquartered in Arlington, Virginia.

Some of the next of kin, however, wanted the remains of their loved ones brought back to the United States and either re-buried in their local cemetery or in one of the many national cemeteries (such as Arlington) around the country. Beginning in 1947, a program for the repatriation of bodies was initiated and until the 1960s when it was discontinued, it was possible to have bodies returned from a foreign grave to the United States at government expense. A large number (171,000) took advantage of this offer, but 97,000 others chose to let their loved one rest among his comrades in the land for which he had fought and died.

Obviously, when dealing with dead and horribly mangled human remains, many of which may be in an advanced stage of decomposition, the mental effect on Graves Registration soldiers is certain to be great. Major Glass recognized this in his 1997 report: “Mortuary affairs soldiers, as well as the soldiers who assist with recovery operations, will definitely experience some emotional or mental discomfort because of the extremely taxing nature of these duties. This discomfort may range from mild to severe. The discomfort and its effects might not manifest themselves immediately.

“Commanders must recognize these facts and plan ways to offset them, especially if the unit will need augmentation from other units to accomplish its mortuary affairs missions. Ways to reduce mental stress include chain of command involvement and assistance from chaplains, psychologists, and social workers. This should be an essential part of peacetime preparation.”

359 American WWII Military Cemeteries

After the war, a Quartermaster report noted, “As of April 6, 1946, there were a total of 359 American military cemeteries containing the remains of 241,500 World War II dead. Estimated number of World War II service dead is 286,959 [that figure has since been raised to around 359,000, although estimates are higher still]. Of this number 246,492 have already been identified: Of the 40,467 who were unidentified as of March 31, 1946, the remains of 18,641 have been located by Graves Registration units. The remaining 21,826 were not reported located up to that time. Of those 18,641 remains which have been located, 10,986 now repose in military cemeteries and 7,655 in isolated graves.”

In addition to eight World War I American cemeteries in Europe, there are also 12 in Europe from World War II (France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Holland, and Italy), one in England, one in North Africa (Tunisia), and one in the Philippines. Except for those remains that may, in the future be found on the battlefields, no further burials may be made in the cemeteries under the American Battle Monuments Commission’s jurisdiction. On occasion, remains are found (even today there are groups of local volunteers digging in the battlefields of Europe in hopes of finding and repatriating war dead) and are respectfully buried in the nearest military cemetery to where the body was located, unless the family requests otherwise.

At some of the cemeteries, many of the local people have lovingly adopted the grave of an American soldier who is unknown to them but has become their “adopted son,” and regularly place fresh flowers at the grave as a way of quietly thanking him for his sacrifice.

Although the name of the Army Graves Registration Service has been changed to Mortuary Affairs, the mission remains the same: to spare no effort in the recovery, identification, return, and burial of deceased personnel, and to assist families during an emotionally difficult time of bereavement.

I was trying to find the cemetery an American soldier is buried in, who was killed in Germany in 1943.

How to trace remains returned from Luxembourg to final burial by local representative (eg, funeral home) of NOK to include dates when possible.

While stationed in Germany in 1978 I decided to take my family to Paris. While driving through Luxembourg I saw a sign for an American Cemetery. I knew that Jim Morrison of the Doors was buried in Paris so I figured this was a cemetery of excentric Americans. I was shocked after passing a subdued German cemetery to see a golden eagle on a marble pedestal telling me this was the American Cemetery Luxembourg. I saw the big display telling me of the 22 cemeteries – 8 WWI, 12 WWII and two in Asia (Philippines and Hawaii). When I asked the American if there was anyone here I might recognize he told me General Patton was buried there with his troops.

I am a career soldier and a history buff and I did not know we had these cemeteries and that Patton was in one of them. I asked the American if he had any information about the cemeteries and he gave me a little pamphlet showing all the cemeteries. When I opened the centerfold I saw there were numerous Cemeteries and Memorials between the German border and Paris. After leaving Luxembourg and using the map in the booklet I visited the WWI cemetery in Oise-Aisne. A British gentleman was there. I was only the second person to have signed the visitor’s log book. Again I asked if there’s anybody whose name I might recognize and he told me Joyce Kilmer was buried about 500 feet from where he was shot. I know Kilmer from his poem “Trees”, his association with Rutgers University and a rest stop on the NJ Turnpike. Again I was shocked. I took a photo of his grave and sent a copy to the Governor of New Jersey, the NJ Turnpike authority and Rutgers to show them their namesake’s grave.

After my visit to Paris where I found the only American Cemetery Suresnes with WWI and WWII names/bodies I contacted General Mark Clark who was the Director of the American Battle Mounuments Commission. I asked him why there was no publicity about all these cemeteries throughout Europe. He told me WWI was so long ago and WWII were normally only family members that were interested. I asked him for any information he could give me and I listed many of the Medal of Honor recipients from WWI or WWII asking where they might be buried. He sent me a booklet on every cemetery, a listing of the graves I asked about and even photos of some of the graves.

I now began a quest to visit as many cemeteries as I could. My wife and three children weren’t too keen about this but I have many photos of them standing behind someone’s grave. I even wrote a article with photos for EURARMY magazine in 1979 and appeared on AFN-TV publicizing the cemeteries. While taking my father-in-law back to the Bulge/Bastogne area were were able to visit the Netherlands (where 190 Texans were having their reunion in place since so many of them died there), Henri-Chapelle (where he found his war dead, took photos and shared them with his war buddies), the Ardennes (where the American told me that people came to visit because they saw me on TV), Luxembourg (he knew Patton) and St. Avold/Alsace (largest WWII cemetery).

Personally my family and I have also visited Meuse-Argonne Cemetery (largest WWI cemetery) where I found MOH Lt Frank Luke, took his photo and sent it to Luke AFB Arizona. In St. Mihiel I found Lts Goodfellow and Keesler whose bases I was stationed at. I visited both cemeteries in Italy. What a shame that so many people visit Paris, Florence and Rome/Naples and are not told/aware that we have American cemeteries there. When we visited Sicily I wanted to take the ferry to Tunisia to see the one cemetery there but my wife didn’t want to spend two days on a boat and go out of our way. Visiting these cemeteries was one of my highlights being stationed in Germany. God bless our Americans who care for these cemeteries and all our military who are buried there so far from home. Previously I had visited our cemetery in Manila and the one in Honolulu not realizing they were part of the larger group. I wish more people would pay respects to our war dead. Perhaps “Saving Private Ryan” gave people an idea about our cemeteries overseas.

Professor Maligno,

Thank you for telling the world of your experiences and of your actions. I ended up on this site while trying to determine what happened to the remains of German POWs that died and one that was murdered by his fellow POWs at the Papago POW Camp in Phoenix, Arizona.

One could spend a busy two weeks in Europe visiting cemeteries of Allied war dead and I now regret never visiting them when I was younger.

Again, thank you

My uncle (my mother’s brother-in-law) SGT Paul J. “Red” Bearden (B Troop/121st Cavalry Reconaissance Squadron/106th Cavalry Group) rests forever with his comrades in arms at the Normandy American Cemetery. While stationed in Germany as a 2nd Lieutenant in 1974 my mother visited and I made a point of going to Normandy to have her visit his grave. It was poignant to salute him (I carried my uniform on this leave) in July, 1974 thirty years after he was killed in action near Lessay.

In July 1994, I again visited SGT Bearden, this time with my oldest son and saluted him again as a Lieutenant Colonel on the 50th anniversary of his death.

Finally, in July 2021, during a river cruise I visited Normandy again as a retired Brigadier General. I had contacted the cemetery director prior to our visit to ask if I get a picture made at his grave and to visit a fellow church member’s wartime sweetheart’s grave, 1LT Rex Caster (she had met met him at Suwanee University in Tennessee. When our tour was at the Normandy Cemetery, a lovely young French woman on the cemetery staff approached me and asked me and my wife and the couple we were travelling with to accompany her in a golf cart. She took us first to 1LT Caster’s grave where she gave me a small bucket. She said that now to make the engraving on the crosses more visible for photos the cemetery provides sand from Omaha Beach to fill the engraving.

Next the young lady took us to Uncle “Red’s” grave where I tearfully spread Overlord sand on his cross and placed American and French flags to salute him. This was a very solemn and respectful way in which our brave men are honored.

The cemetery at Normandy stands at the top of a 100 foot bluff above the beaches that the young men of the 1st Infantry (the Big Red One)and 29th Infantry (Blue and Gray) Divisions assauleted on June 6, 1944. A poignant story about the sacrifice of the 29th is that of “The Bedford Boys” (by Alex Kershaw) – 19 young men from Bedford, Virginia (population 3,000) who died in the first wave at Omaha. (If you can’t visit Normandy visit the National D-Day Memorial in Bedford which memorializes not just Bedford’s sacrifice but the sacrifice of all who fought on D-Day.)

Even today there are efforts in Normandy to recover the remains of soldiers who fought in Normandy. Another member of my uncle’s unit who was killed in Normandy was PVT Ronald Wilson. His name is on the Wall of the Missing at the Normandy Cenetery. PVT Wilson’s nephew has been trying to locate his remains based on information from surviving residents of the town of Fougere. He learned that his uncle’s body was taken from his M5 tank after it was destroyed by a German tank and buried several hundred yards away. in 2018, the possible burial site was excavated bu vno remains were found, only one GI dungaree button. It is speculated that the burial site was excavated after World War I and the remains were unable to be identified and interred in a temporary cemetery as “UNKNOWN” and later moved to one of the permanent cemeteries.

One thing not mentioned in the article by Mr. Webb is that the majority of the Graves Registration Units (both in WWI and WWII) were integrated black units with white officers. These U.S. servicemen did a gruesome, sickening and thankless task that needs to be recognized and appreciated.

I shared a hospital room with a man who spent 11 months in Saigon in a Grave Reg unit. Suffice it to say…he did not sleep well.

Are the Grave Registration unit logs of KIA recovered by location? Records of interest 35th INF DIV 137 INF Regiment 3rd BN, L Company, Villers la Bonne Eau 30 DEC44 > JAN 45

I too have visited several military cemeteries in Europe, including (in 2008) the well-known U.S. cemetery overlooking Omaha Beach. Because I’m Jewish I paid special attention there to the graves marked with a Star of David, taking photos of a number of them.

One day a couple of years later I was looking at the photos and while reading the information on one of the markers, I suddenly wondered how much about this particular soldier (a PFC David Tenenbaum) I could find out. The marker indicated he was in a 90th Div. infantry regiment and died in about the third week of June ’44. Via internet searching, I learned that his regiment arrived on Utah Beach on about D+3. So he was only in combat for a few days before he was KIA.

Turns out that PFC Tenenbaum was a salesman in Erie, Penn., before the war; about 22-23 yr old when he died. I contacted the 90th Div. Association to see what info they may have had about him. The had a wide panorama photo of his rifle company taken before leaving the U.S.A. A list of names of the soldiers revealed PFC Tenenbaum to slightly resemble a popular actor of the day named Dennis Morgan. I wanted to look up Tenenbaums in Erie to see what further info about the soldier I could find. But I just couldn’t figure out a way to initiate contact without sounding odd or suspicious. Imagine, after all, an inquiry out of the blue about, let’s say, an uncle one had never met, about whom one knew little more than he’d been killed in WWII.

PFC Tenenbaum was awarded the Silver Star in action that led to his death. My 90th Div. contact suggested I could possibly get PFC Tenenbaum’s company’s morning reports from the days around when he died, and perhaps find out more, and maybe track down the citation. That proved to be very complicated; my digging led me to a series of screen prompts from such-and-such a government archive telling me that staff shortages and such prevented them from helping me. (Our tax dollars hard at work!)

An upbeat ending to the story is that in appreciation for the help rendered by the 90th Div. Association, I became a paid-up member for a couple of years. Also, in 2011, I once again visited Normandy, this time with my wife, and we visited PFC Tenenbaum’s gravesite. Per Jewish tradition, I placed a small stone on his headstone to commemorate my visit.

As I write this, it dawns on me that I’ve sort of adopted PFC Tenenbaum as an uncle who died during the war. (Two of my actual uncles — one a brother to my father, the other a brother to my mother — served in combat during the war. The former was an infantry master sergeant in No. Africa, Sicily, and Italy, the other a naval aviator flying a Hellcat on U.S.S. Santee in the Philippine Sea in 1944. Both lived well into their nineties.)