By Mason B. Webb

In 1979, Dr. Hugh Thomas, a British physician, came out with a highly controversial book that made the startling claim that Nazi Germany’s Deputy Führer, Rudolf Hess, did not commit suicide in Berlin’s Spandau Prison in 1987, but actually died in 1941, and that the man who died in prison was, in reality, Hess’s double!

Since 1979, more research has been done regarding Thomas’s astounding assertions, and a fresh look needs to be taken at the controversy.

Rudolf Hess: Hitler’s Loyal Secretary

First, who was Rudolf Hess? He was born in Alexandria, Egypt, the son of a German importer/exporter, on April 26, 1894. Moving back to Germany in 1904, the young Hess was schooled in Switzerland and was being prepared for a career in business. But the Great War derailed those plans. Hess enlisted in the 7th Bavarian Field Artillery Regiment and was sent to the front, where he earned the Iron Cross, second class. He suffered a chest wound and, after recuperating, was transferred to the Imperial Air Corps. He became a pilot in a Bavarian squadron and was promoted to lieutenant a few weeks before the war ended.

Greatly upset by Germany’s capitulation, and still of a military mind, Hess settled in Munich and joined two paramilitary organizations. After hearing upstart Adolf Hitler speak in 1920, Hess joined the Nazi Party and became a devoted follower of Hitler, earning the future Führer’s trust.

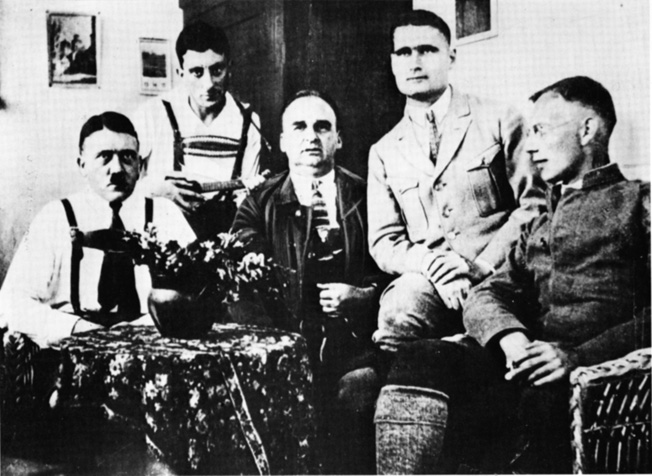

After Hitler and the Nazis tried and failed to overthrow the Bavarian government in November 1923, Hess and Hitler were both jailed at Landsberg Prison. There Hitler dictated his autobiography and vision for the future to Hess, who became his secretary.

After their release from prison, Hess, along with Heinrich Himmler and Hermann Göring, became one of Hitler’s closest associates. It was Hess who would introduce Hitler at Nazi Party rallies, stirring up the masses to a fever pitch with prolonged shouts of “Sieg, Heil!” (“Hail, Victory!”) like some demented cheerleader.

Shortly after Hitler became German Chancellor in January 1933, Hess was elevated to the position of Deputy Führer, but the title was more ceremonial than substantive, for the beetle-browed Hess, who often appeared to be nothing more than Hitler’s dim-witted stooge, lacked the intelligence and cunning necessary to be a force within the Third Reich hierarchy. William Shirer, author of The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, lumped Hess in with the “weird assortment of misfits” that characterized the leadership of Nazi Germany.

Yet Hitler was as faithful to his loyal follower as Hess was to him, and proclaimed that, should anything happen to both him and Göring, Hess would be next in line to become Führer.

Hess’s Secret Mission

After Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, and France and Great Britain both declared war on Germany, Hess became agitated, because he had hoped that Britain would join Germany in a war against their common foe, the Soviet Union.

In May 1941, a month before the surprise invasion of the Soviet Union, Hess decided to take matters into his own hands and embark upon a secret mission that not even Hitler knew about or had authorized.

Taking off from the Messerschmitt factory airstrip in the Bavarian city of Augsburg on May 10, Hess flew a twin-engine Messerschmitt Bf 110E solo to Scotland in an attempt to negotiate peace with Britain. When he learned about Hess’s flight, a furious Hitler dispatched German fighters to intercept him, but Hess had escaped German airspace.

After a four-hour journey of almost 1,000 miles, Hess crossed the British coast over Ainwick in Northumberland, managed to avoid being shot down by the RAF, then flew on toward his Scottish objective, Dungavel House, home of the pro-peace Duke of Hamilton. With his fuel supply running low, Hess parachuted out over Renfrewshire at 11 pm and broke his ankle upon landing at Floors Farm near Eaglesham. A farmer took Hess into custody at the point of a pitchfork.

Detained by the local Home Guard and then transferred into Army custody, Hess asked to see the duke, whom he hoped would be sympathetic to his efforts to reach Prime Minister Winston Churchill; their meeting came to nothing.

Hess explained later to various interrogators that the purpose of his unannounced visit was simply to seek peace between Britain and Germany. Churchill derided Hess’s naïve efforts as those of someone without all their mental faculties, and Hitler, too, issued a statement saying that Hess was mentally disordered and “a victim of hallucinations.”

Remaining in custody throughout the war, mostly at Maindiff Court Military Hospital in Abergavenny, Wales, Hess became increasingly paranoid, believing that German agents were trying to kill him by poisoning his food.

Death in Spandau

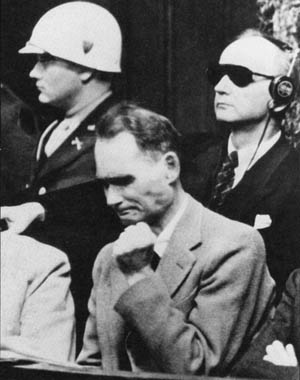

In 1946, he was tried with the other surviving high-ranking Nazi officials by the International Military Tribunal at the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials, where he showed signs of amnesia and mental illness. He seemed to take little interest in the proceedings, often making incoherent statements and exhibiting odd behaviors in the courtroom.

Found guilty of “crimes against peace” and “conspiracy with other German leaders to commit crimes,” he was sentenced to life in prison at Spandau Prison where, despite several requests for release on humanitarian grounds, he remained until his suicide in 1987.

The official news release about Hess’ death said, “Rudolf Hess hung himself from the bar of the window of a small building in the prison garden, using the electric cord of a reading lamp. Efforts were made to resuscitate him. He was rushed to the British Military Hospital, where, after several further efforts, he was pronounced dead at 4:10 pm local time.”

Such a factual statement should have been the end of the story but, as we shall see, a new chapter was just beginning.

Did Hess Have a Doppelgänger?

Hess’s strange attempt to bring about peace negotiations, the odd behavior at his trial, and his subsequent lifelong imprisonment have given rise to many bizarre explanations about his motivation for flying to Scotland, his long incarceration at Spandau as “Prisoner Number Seven” (the last two inmates held at Spandau, except for Hess, were former Third Reich Armaments Minister Albert Speer and former Hitler Youth leader Baldur von Schirach; they were freed in 1966), and questions surrounding his death. Conspiracy theories abound.

Dr. Hugh Thomas, who had been a physician at Spandau and had personally examined Hess closely on several occasions in 1973, has an explosive explanation: Spandau Prisoner Number Seven was actually a “double” for the real Hess!

It is now known that some high-ranking political and military figures in World War II used doubles––stand-ins who resembled the famous person. The use of look-alikes, “political decoys,” or doppelgänger had several advantages; first, a double could attend functions such as social gatherings or review parades while the actual person attended to more important business. Second, enemy spies could be fooled into thinking the real person was in one location when, in fact, he would be entirely elsewhere. Third, in the event of an assassination attempt, it would be the double who would be killed or wounded, not the actual person.

British Field Marshal Sir Bernard Law Montgomery had a double who bore a striking resemblance to him––an Australian actor named M.E. Clifton James (he later wrote a book and starred in a movie with the same title, I Was Monty’s Double). Winston Churchill apparently did not have a “body double,” but, as rumor has it, had a “voice double”––Norman Shelley––whose manner of speaking was so close to Churchill’s that some believe he made broadcasts over the BBC pretending to be the real prime minister. In Germany, SS chief Heinrich Himmler allegedly had a double, and Adolf Hitler also reportedly had several men who performed “double duty” from time to time.

Dr. Thomas’s Doubts

In his book, Dr. Thomas said that he first became suspicious when he examined Hess and could find no sign of the scarring that Hess’s World War I wounds would have left on his torso. According to Thomas, Hess’s medical records said that he had been shot through the left lung, the bullet entering just above the left armpit and exiting between the spine and left shoulder. Such a wound would have left a visible mark, but Thomas found none.

(This finding of no scars appeared to be confirmed during the two separate autopsies that were performed on Hess’s body; however, when Hess’s full medical records were released, it was revealed that the bullet wound was in a different place than Thomas had claimed, and that scarring from the clean shot was likely minimal.)

Next, Thomas said that the prisoner had frequent bouts of sudden diarrhea whenever he was questioned by the authorities, and that he acted at other times as if he had amnesia. He refused to allow his wife and son to visit him until 1969––perhaps another sign, said Thomas, that Prisoner Number Seven was not, in fact, Hess; they would have immediately noticed dissimilarities between the real Hess and the double; the intervening 28 years would have dulled their memories.

Even the eventual visits by his family members brought no signs of recognition by the prisoner. Thomas said that such behavior is explainable because a double would not necessarily know all the details of the life of the person he is portraying; faking amnesia would absolve the double of his inability to recognize names, dates, and places brought up in conversation.

Two Aircraft?

With suspicions about Prisoner Number Seven’s true identity raising red flags in his mind, Thomas looked deeper into Hess’s background. He reproduced a photograph in his book that purported to show Hess taking off from Augsburg on his fateful May 10 flight. The Bf 110E is shown without long-range drop-tanks, leading Thomas to surmise that the twin-engine plane could not have flown the entire distance from Bavaria to Scotland without refueling––and there is no indication that Hess landed to refuel.

That calculation led Thomas to another theory: that two aircraft were involved.

As “proof” of the latter supposition, Thomas cites the fact that the tail number of the photographed plane in which Hess allegedly flew from Augsburg was not the same as the tail number of the Messerschmitt that crashed in Scotland (today that tail is on display in the Imperial War Museum in London).

However, there is no assurance that the photo in the book of Hess supposedly taking off was a photo of his actual departure; he apparently took some 20 training flights in Bf 110E aircraft before departing for Scotland, so this photo could have been taken of any of them. And if he had flown in a Bf 110E with drop-tanks, he would have had a more-than-adequate range of 1,560 miles.

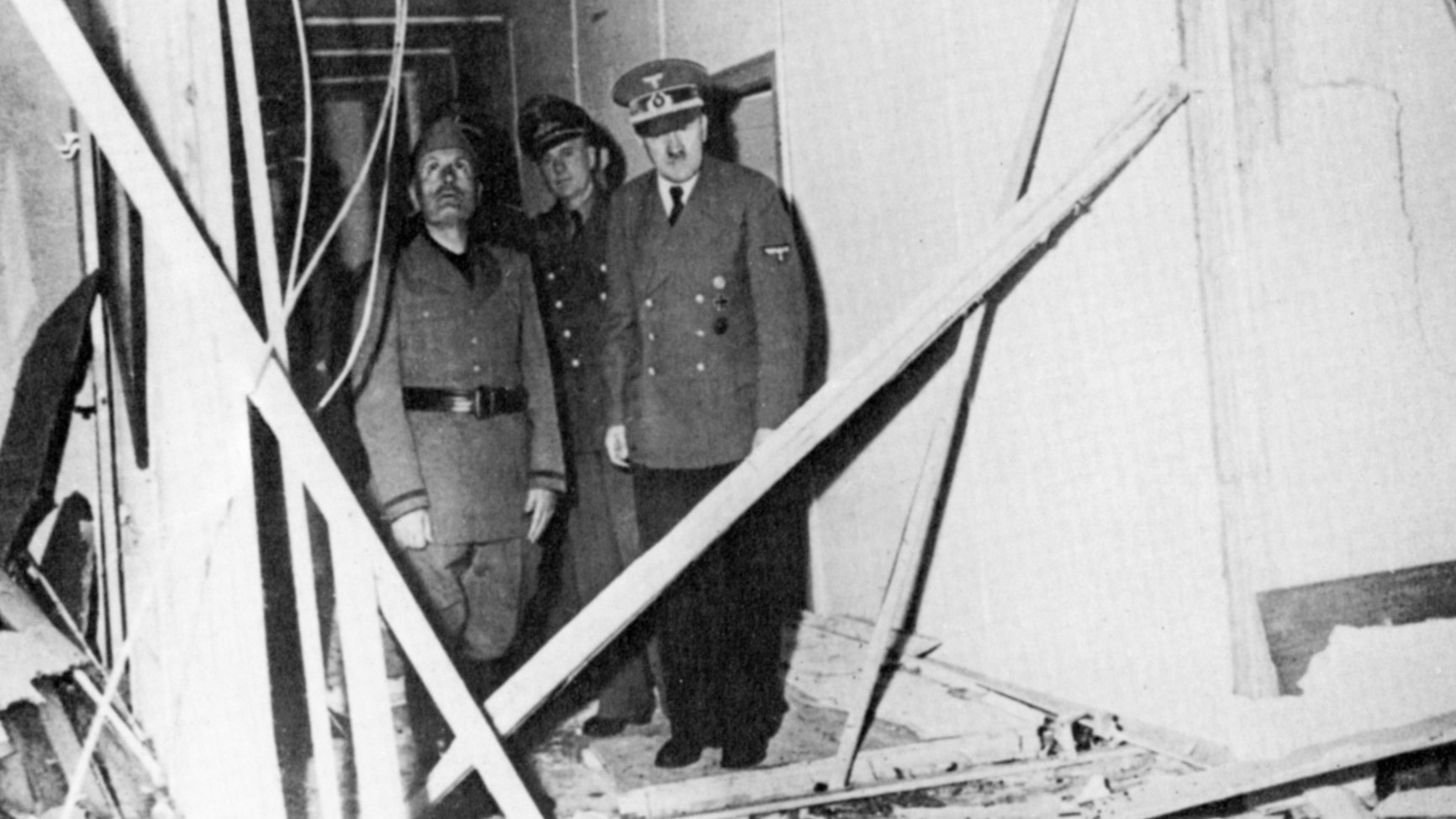

Thomas speculates that, once Hitler learned of Hess’s flight (a flight he viewed as an act of treachery), he ordered Luftwaffe planes to shoot down the Deputy Führer. With the real Hess dead, Hess’s double was then dispatched in a different plane from northern Germany and continued on to Scotland.

Of this theory, one author notes, “The claim is only credible if Göring and others had advance knowledge of the Hess flight, and opposed it, which raises the question of why Hess was allowed to take off from Augsburg in the first place. In the same vein, some have claimed that it would not have been possible for Hess to have flown over German territory without prior authorization, but this is convincingly countered by Roy Nesbit and Georges Van Acker in their book, The Flight of Rudolf Hess (1999).”

Further, in a postwar statement in his 1955 memoir, The First and the Last, Adolf Galland, the future Luftwaffe fighter ace, said that early in the evening of May 10, 1941, he and his entire group had been ordered by Göring to shoot down Hess’s plane. Galland said that he sent up only a token force in response and that Hess was not shot down.

Not Suicide, But Murder?

Eight years after Thomas’s book came out, another bombshell struck: Hess and/or his double didn’t commit suicide. His supposed double was murdered on August 17, 1987, to cover up the fact that he, the double, wasn’t Hess!

It all started with a BBC broadcast on February 28, 1989, in which Abdallah Melaouhi, who had been Hess’s medical attendant at Spandau since August 1982, contradicted the official suicide statement. Melaouhi said that when he entered the temporary summer house in the garden where Hess was said to have hanged himself, he saw that “everything was topsy-turvy, yet the [lamp] cord was in its normal place and still plugged into the wall.” Two Americans in uniform were also there, further arousing the Tunisian orderly’s suspicions.

Also throwing more fuel on the fire were Hess’s son, Wolf Rüdiger Hess, and Alfred Seidl, Rudolf Hess’s lawyer at the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials. They noted that the elder Hess was in poor shape, medically speaking, and that the arthritis in his fingers was so bad that he could not even tie his shoes, let alone fashion a noose made from a lamp cord. They also asserted that a suicide note was forged.

In addition, in their minds, the two Americans in uniform were, in fact, two secret British MI6 agents who strangled Hess to death.

In May 1989, the conspiracy theory gained new legs. That month, the respected French weekly magazine Le Figaro published an article by Jean-Pax Méfret that suggested Hess’s death was something other than suicide. Méfret based his story on a meeting he said he had had the previous year with an unnamed “Allied officer” stationed in Berlin who told him that Hess did not commit suicide.

The next day, this same officer told Méfret to forget what he had told him, saying that the summer house in which Hess had apparently killed himself had burned down within 48 hours after the event. “Even the cord which Hess supposedly used to hang himself has gone up in smoke,” said the officer. “No one will ever be able to prove that this old Nazi didn’t kill himself.”

The Hess family, too, remained suspicious about the official story of how the 93-year-old prisoner died, and so hired Dr. Wolfgang Spann to perform a second autopsy. Spann’s detailed examination of the marks on Hess’s neck reportedly revealed a different cause of death than that of the Four Powers’ pathologist, J.M. Cameron. Spann’s report noted that Hess had died from strangulation, not by hanging with an electrical cord! However, Spann publicly stated, “We can’t prove a third hand participated in the death of Rudolf Hess.”

Why Kill Rudolf Hess?

If Hess was murdered as the result of some conspiratorial plot, what could have been the motive? Certainly the issue of the cost of keeping him locked up could have been a factor. The price tag for maintaining Spandau Prison, with its 600 empty cells, 100 full-time employees, guard detachments provided by Berlin’s governing Four Powers––France, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and the United States–-and only one prisoner was more than $100 million annually.

For years, France, Great Britain, and the United States wanted to close the prison and release the aging Hess, but the Soviets would have none of it. Rudolf Hess would stay in Spandau until he died, they insisted.

But why murder a 93-year-old man who was reportedly in poor and failing health? How much longer could he be expected to live? Anyone consulting an actuarial table would conclude that his continued existence would not be a financial burden on the governments of the Four Powers for much longer.

It was only later, when Soviet reformist President Mikhail Gorbachev was in power, that the Russians changed their tune. According to Hess’s son, after the Soviets relented and said that Hess should be released, the British would not allow it, and hatched a plot to do away with his father. But why? To cover up the fact that Prisoner Number Seven was actually a double? Wouldn’t such a disclosure bring about extreme embarrassment for the British, as well as for France and America?

The Many Alternative Theories on the Death of Rudolf Hess

Others began taking pot-shots at Thomas’s theories immediately after the book’s publication and coming up with their own. Since Thomas’s controversial book came out, a plethora of others have been written on the subject (Hess: Flight for the Führer by Peter Padfield; Ten Days That Saved the West by John Costello; Churchill’s Deception by Louis Kilzer; British Secret Service and 17F: The Life of lan Fleming by Donald McCormick; Double Standards by Picknett, Prince, and Prior; and Hess: The British Conspiracy by John Harris and M.J. Trow), each one filled with more conjecture and counter-theories than the last and calling into question the theories advanced by the other authors. They make for fascinating reading but whether or not any of them get any closer to the truth of the matter is debatable.

Perhaps the most authoritative account of Hess’s death came from Lt. Col. Tony Le Tissier, the former British Governor at Spandau Prison. In his 2008 book, Farewell to Spandau, Le Tissier contradicted medical orderly Melaouhi’s statement by pointing out that there were four reading lamps in the summer house and, therefore, more than one cord. The two men in American uniform were medics, not nefarious MI6 agents, who had been called to assist with the attempts to resuscitate Hess, and the “topsy-turvy” furniture had been pushed aside in the course of their previous efforts to revive the prisoner.

As for Hess’s medical condition and supposed debilitating arthritis, Le Tissier said that the prisoner wore a truss and probably found it restricting when bending over to tie his shoelaces, but he could write legibly and thus tie a knot, proving that arthritis did not preclude him from hanging himself.

Perhaps the truth is that there was no conspiracy, no double, no second plane, no murder, no deeper, hidden motive. Perhaps Rudolf Hess, already mentally ill and sick with fear in 1941 about what might happen to his beloved country if Germany invaded the USSR, had only one goal in mind––that of reaching Britain in hopes of making peace. Could such a simple, unadorned explanation be correct, after all?

The official British files relating to Hess that have been kept secret for decades are scheduled to be released to the public in 2016. Perhaps then the world will finally learn the truth about Rudolf Hess. n

A gentleman I know, a former special forces medical NCO, attended to Hess’s needs in Spandau. He said that Hess probably didn’t hang himself. The arthritis in his shoulders was so severe; he couldn’t have lifted his arms high enough to secure the wire or rope. He believes Hess was murdered.

Murdered or not, it is a fact that Hess “lived too long” and was an embarrassment and irritant too all concerned. I remember in 1987, it was a one day story and then put aside except for a few annoying reports like those cited here.