By Jan Bos

It was a beautiful September day over Holland. Gradually, a faint rumble began to grow, and the sunny sky was darkened. This was not caused by a sudden increase in clouds but by more than 1,100 American C-47 transport planes carrying some 20,000 paratroopers of Lt. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton’s First Allied Airborne Army, consisting of three Allied airborne divisions and an airborne brigade, into battle.

Aboard one of the C-47s in the aerial armada, a plane dubbed Bette by its pilot, were 15 heavily laden paratroopers of H Company, 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division. After taking off from their English airfield at RAF Spanhoe, they had been in the air for over an hour. The usual lighthearted horseplay and banter that had characterized their training in England was absent. They knew that a hot reception awaited them, and they were about to jump into a hornet’s nest. However, none of them could guess just how hot it would be.

Their officers had briefed them about the mission, calling it Operation Market-Garden and passing along the information that it might just shorten the war. Many of the paratroops, however, worried that the only thing it would shorten would be their lives.

An Ambitious Plan to Shorten the War

After the airborne and amphibious landings in Normandy four months earlier, the Allies finally were able to break through the German defensive positions in northern France. By mid-August the Germans were on the run; at least this is what Allied headquarters thought. The Germans still offered stiff resistance during their strategic withdrawal, and the Allies were doing their best to overcome this resistance. German positions were under constant artillery fire, and American and British bombers pounded their positions.

As the Germans retreated, additional American, British, Canadian, Polish, Norwegian, and Free French divisions poured into France from staging areas in England and rushed southward and eastward. The important harbor of Cherbourg was captured at the end of June, and Paris was liberated in August. Near St. Lô, however, mistakes were made and bombs fell accidentally on American positions, killing and wounding many men. By September 1944, the Allies were inside Holland and continuing to push the enemy back toward its homeland.

To keep the pressure on the Germans and to utilize the airborne forces, plans were drawn up for an airborne assault behind enemy lines. One of these plans was a major parachute drop near Tournai in Belgium. Airborne forces were alerted and moved to their designated airfields in England, but the mission was cancelled when Allied ground troops overran the drop zones. The Germans were really on the run! Still, planners continued to think about ways paratroops and glider forces could be introduced into the battlefield in an effort to trap large numbers of the enemy and perhaps even shorten the war.

On September 10, 1944, 37-year-old Brig. Gen. James M. Gavin, commanding general of the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division, and Colonel John Norton, the division’s G-3 (operations officer), were summoned to a meeting at Allied airborne headquarters in London. There Gavin and Norton were introduced to a new airborne operation in which American, British, and Polish airborne troops would play a leading role.

It was a daring plan named Market-Garden, with “Market” the code word for the coup de main parachute and glider phase, and “Garden” the British XXX Corps’ tank and infantry assault portion. After the night drops on D-Day, June 6, 1944, in which there had been considerable confusion and widespread scattering of the paratroops, planners decided to make Market-Garden a daylight operation. Very little time was allotted for planning and preparation. The jump was scheduled to take place on Sunday, September 17, 1944, only seven days away! It would have been a risky, ambitious operation even if it had been seven months away.

The target for Market-Garden was southeastern Holland, the location of several important bridges over key waterways leading into the part of Germany not heavily defended by the Westwall or Siegfried Line. Selected to take part were the U.S. 101st and 82nd Airborne Divisions and the British 1st Airborne Division, reinforced by the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade.

Objectives for the 82nd

As the plans were drawn up, the 101st would land north of the city of Eindhoven, capture bridges across the Zuid Willemsvaart and the Wilhelmina Canal, then take the cities of Veghel, Son, and Eindhoven. The Screaming Eagles, as the 101st was known because of its distinctive insignia, would drop nearest to the British ground forces coming up from the Dutch-Belgian border.

The 82nd Airborne Division, nicknamed the All Americans, would arrive at DZ (drop zone) “O,” at Overasselt, and on DZs “N” and “T,” northeast and southwest of Groesbeek. Their task was monumental: capture the bridges over the Maas River at Grave, the Maas Waal Canal, the railroad and highway bridges across the Waal at Nijmegen; Nijmegen itself; the villages of Grave, Overasselt, Groesbeek, and Beek; then take and hold the high ground between Groesbeek and Berg en Dal. The 82nd’s area of operations was 57 miles from the closest British ground forces.

The British and Polish paratroopers and glider infantry would come down west of Arnhem, where their mission was to capture and hold the bridges over the Rhine River at Arnhem, about 10 miles north of Nijmegen.

Everything depended on the airborne forces being able to hold the bridges until the armor and infantry could reach them. It was a staggeringly audacious plan, made even more surprising by the fact that British Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery, known for his meticulous set-piece battles and his disdain for acting without long periods of painstaking preparation, had come up with the idea.

As soon as the meeting in London was over, Gavin and Norton sped back to their headquarters, called their staff together, and informed them about the plans. With time short, the men immediately went to work. The staff quickly wrote up the plans and operation orders, and unit commanders pored over maps, examining the terrain and enemy positions where their troops would be dropped.

The 504th Spearhead

One of the 82nd Airborne units chosen to take part was the 504th Regimental Combat Team, which included the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment, the 376th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion, and C Company, 307th Airborne Engineer Battalion. The 82nd Airborne Division’s 504th PIR had not participated in the invasion of Normandy because it needed to be built back up after the heavy casualties suffered during the July 1943 invasion of Sicily and the subsequent costly fighting in Italy; the 504th did not arrive in England from Italy until April 1944. After enjoying a well-deserved rest, the 504th received replacements and went back to training while their comrades left for Normandy. Now it would be the 504th’s turn again to be the spearhead against the enemy.

The 504th’s mission was to land on DZ “O,” capture the huge nine-span bridge over the Maas River at Grave, capture at least one of the bridges over the Maas Waal Canal, and mop up the area between Grave, Overasselt, and Heumen.

The 504th’s timetable was as follows: two C-47s equipped with radar beacons would drop Pathfinders on DZ “O” at 1:13 pm to mark the drop zone; 1st Battalion would drop two minutes later. Second Battalion, less E Company, would drop at 1:17; E Company would be dropped west of the Maas River to capture the key bridge there. Third Battalion would follow suit in the taking of this bridge, the lifeline between the 82nd and the British ground forces, which had to be held at all costs.

Troop Carrier groups of the IX Troop Carrier Command, U.S. Ninth Air Force, were also alerted, and they began readying their fleets of transport planes; 7,250 All American paratroopers would be dropped by 480 C-47 and C-53 transport planes of the 50th and 52nd Troop Carrier Wings. After the paratroops were dropped, the same planes would return to their bases, hook up hundreds of Waco CG-4A gliders, and, the next day, tow the engineless craft to their LZs (landing zones).

One of the aviation units from the 52nd Wing was the 315th Troop Carrier Group, stationed at RAF Spanhoe, about 80 miles northwest of London in Northamptonshire. The 315th’s mission for September 17 was to drop the 504th PIR on DZ “O” at Overasselt.

The 315th’s commanding officer, Colonel William L. Brinson, was briefed about the operation, and he and his staff went to work immediately, meeting constantly with the officers from the 82nd to work out the thousands of details and to coordinate the drop, as well as preparing the aircraft for their roles.

It was also vital to carefully study aerial photos, determine where the German anti-aircraft positions were, and find routes to the DZs that would avoid the groundfire as much as possible.

D-3

It was now D-3: Friday morning, September 14, 1944. The paratroopers from the 504th climbed into trucks that took them from their cantonment area to the Spanhoe airfield. As soon as the last truck entered the airfield, MPs closed the gates and put up tight security; no one was permitted to enter or leave the base, and no incoming or outgoing phone calls were permitted. The paratroopers moved inside a hangar on the base that would be their home until the operation began.

Aerial photographs of the targets and detailed sand table models of the operational area were made available. Both paratroop and troop-carrier officers were briefed about the upcoming mission, now just two days away. The paratroopers and glider troops were then briefed and issued maps of Holland and Dutch guilders (invasion money).

Saturday was spent loading heavy equipment, bazookas, ammunition, antitank mines, food, water, and blood plasma into parapacks (parachute-dropped cargo containers). Radios, the basic load of ammunition, grenades, and two boxes of K- and one box of D-rations were issued to the men. The parapacks were delivered to the airfield where they were attached beneath the transport planes.

Red Cross units, from which the men could get coffee and cigarettes, were set up around the fields. Letters home were written and stored; none would be sent until after the operation was under way. The aircrews were given a short lecture on “Escape and Evasion in Holland,” and escape kits were issued. The tension was building but the men were eager to go.

In the early morning of D-Day, Allied bombers, escorted by American and British fighter planes, headed east to bomb and strafe known enemy positions in Holland.

207 Pounds of Equipment

Back at the troop-carrier bases in eastern England, the paratroops and their pilots were making final preparations. At 6:15 am, there was a breakfast of hotcakes, syrup, cereal, fried chicken with trimmings, butterscotch pudding, hot coffee, and apple pie. The men were able to attend church service, followed by a last-minute briefing. The crews were then taken out to their planes.

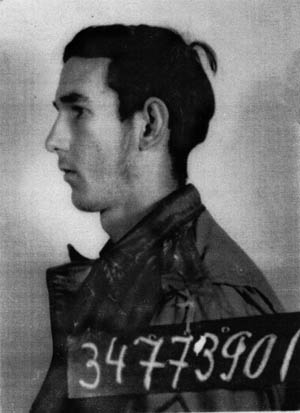

One of the 90 planes lined up at Spanhoe, a brand new C-47A nicknamed Bette, tail number 43-15308 (34th Troop Carrier Squadron, 315th Troop Carrier Group), awaited her five-man crew that consisted of Captain Richard E. Bohannan (pilot), 2nd Lt. Douglas H. Felber (copilot), 1st Lt. Bernard P. Martinson (navigator), Staff Sgt. Arnold B. Epperson (radio operator), and Sergeant Thomas N. Carter (crew chief).

Like a mother hen, Sergeant Carter had been hovering around his airplane since the early morning, checking every inch of it. He had arrived in England in June 1944 and was assigned to the squadron as a replacement; the Holland mission would be his first operational mission.

Shortly after the crew reported for duty, the 15 paratrooper passengers from H Company, 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division, arrived, jumping from the truck and lining up at the plane’s portside door. The men in the “stick” were 1st Lt. Isidore D. Rynkiewicz (jumpmaster), Sergeant Earl V. Force, Corporals James C. Bailey and Lawrence J. Demont, Pfcs. Joseph A. Foley, Norman R. Handfield, Walter P. Leginski, John F. McAndrew, Everett R. Rideout, and William F. Stewart, and Privates Roy M. Biggs, Mark L. Kaplan, Richard C. Reardon, George Willoughby, and Donald F. Woodstock. All but Corporal Demont had seen battle in Sicily and Italy; Demont was a recently arrived replacement and hardly knew the others.

Everyone sported the 82nd Airborne Division shoulder patch high on the left sleeve of their khaki jump jackets and a small American flag on the right sleeve.

Private Richard Reardon recalled that he, like the others, was loaded down with heavy equipment. He wore two parachutes, main and reserve, a Thompson M1928A1 sub-machine gun with a loaded magazine plus four extra double magazines, a Colt M1911A1 .45-caliber pistol plus two loaded seven-round magazines, an antitank mine, a Gammon grenade, and four fragmentation hand grenades. To add some more weight, he carried 300 rounds of .45-caliber ammunition, a nine-inch steel jump knife, wool blanket, canvas shelter half, first-aid packet, compass, entrenching tool, several boxes of K-rations, a mess kit, canteen, carton of cigarettes, and several chocolate bars. Before struggling out to the plane, Reardon found a scale and weighed himself: 392 pounds. His normal weight was 185 pounds! All the men also wore Mae West life preservers that ballooned in front of their chests.

Beginning the Largest Airborne Operation of the War

Rynkiewicz gave the order to harness up, and the men helped each other attach their parachutes. Then the order was given to load up and the men started to climb the steep ladder into the airplane. Being so heavily laden, the men had difficulty getting aboard, but helping hands from fellow troopers and Sergeant Carter enabled them to board the plane. The men took their positions on wooden benches on both sides of the plane’s cabin and strapped themselves in. Many of the combat veterans were delighted to go back into action but apprehensive, too.

The air crewmen put on their flak vests and helmets, and Sergeant Carter took his place near the open door; his task would be to pull the static lines in after the paratroopers had jumped.

The engines of 90 planes were cranked and turned over, filling the air with puffs of blue exhaust and a growing volume of noise. The planes then rolled to the end of the runway to await the signal to take off. It was 10:39 am when the first of the 315th planes lifted off from Spanhoe; the rest followed in rapid succession.

The planes circled the airfield until all had taken off and joined the 315th serial (Serial A-11). On board were 1,240 paratroopers with 473 parapacks carried beneath their fuselages. For the paratroopers, this was a one-way journey with no return ticket.

The planes flew in two 45-plane formations made up of V-of-V serials. Once aloft, the 315th rendezvoused with other troop-carrier groups coming from other RAF fields. Escorting the troop-carrier train were North American P-51 Mustangs, Republic P-47 Thunderbolts, and British Supermarine Spitfire fighter planes. It was the largest airborne operation so far in the war and presented a magnificent sight. The spectators on the ground could see more than 4,500 planes (transports, bombers, fighter planes, and gliders) passing overhead, a sight they would never forget.

The serial flew for 20 miles to Checkpoint March, then 69 miles to Aldeburgh in eastern England. Soon the armada passed the English coast and started to cross the North Sea, heading for Holland. The route over water was 93 miles. The weather was perfect; over the North Sea the visibility was between six and eight miles. There was 8/10ths stratocumulus cloud cover at 3,000 feet.

Some of the paratroopers fell asleep in the droning planes, and some of them talked to each other or smoked while others looked outside, contemplating the coming battle. The flight over the North Sea was uneventful. Below, several rescue barges could be seen on the water, just in case some of the planes had to ditch.

Soon the Dutch coast loomed ahead, and the Dutch islands were passed. Men in the transports looked down and saw mile after mile of terrain, sparkling in the sun, that had been flooded by the Germans; many houses and farms were partially or wholly under water. Down below, the unsuspecting people of Willemstad were attending church services.

Bette Takes Flak

As the aerial armada passed the Dutch coastline and crossed into enemy-held territory, German antiaircraft guns opened up, shattering the Sunday morning calm. An antiaircraft battery, consisting of an 88mm and two 37mm guns, was positioned on and near a bunker at Dintelsas and began blasting away at the incoming planes. Black bursts of flak exploded between the transport planes. The aircraft were also fired upon by heavy machine guns; tracer bullets could be seen coming up at the planes like bright spiderwebs. Three or four Allied fighter planes broke formation and dived down to silence one of the flak batteries, killing several German soldiers.

Damage had already been done. There was a victim: C-47 tail number 43-15308—Bette.

One of the six parapacks beneath Bette had been hit and was on fire. The container held Composition C, a highly dangerous and combustible material used to make explosives. The Comp C was burning, and flames were spreading to the other parapacks under the fuselage, which also caught fire. The fire was so intense that it melted holes in the aluminum floor of the aircraft. Bette’s left engine was also ablaze.

Inside the plane, the paratroopers who, just moments before, had been sitting on both sides of the cabin, thinking of the upcoming battle in the Grave-Nijmegen area, chewing gum, smoking cigarettes, and trying to calm their nerves, were now in a panic. Bullets and shards of antiaircraft shells punctured Bette’s thin skin, and flames were eating up the floorboards. Crew Chief Carter informed the pilots of the fire over the intercom.

In another C-47, 1st Lt. William M. Perkins was flying some 600 yards behind Captain Bohannan at an altitude of approximately 1,000 feet. Seeing flames trailing behind Bette, Perkins broke radio silence and called Bohannan: “Bo, your parapacks are on fire!” Since Perkins did not receive a response, he repeated the same call several times. Then he saw paratroopers starting to bail out of the burning aircraft.

Inside Bette, it was chaos. During the flight, Pfcs. Walter Leginski and Everett Rideout had been sitting just opposite the door next to the jumpmaster, Lieutenant Rynkiewicz. All three were slightly wounded by shrapnel in their legs and buttocks when the plane was hit; several other paratroopers also received minor injuries. Soon the interior filled with smoke and someone yelled to get out of the airplane; this was an order that did not need to be repeated. Both Leginski and Rideout noticed the crew chief jump from the plane and that Lieutenant Rynkiewicz was slumped forward in his seat. Leginski and Rideout did not hesitate, and out they went. Someone must have thrown Lieutenant Rynkiewicz out of the plane, since he survived the crash.

Everyone was tumbling out now. While trying to get to the door, Pfc. Reardon fell onto the burning floor. Suddenly, the floor gave way and he fell out through the bottom of the burning fuselage. Miraculously, his parachute opened. He looked up and checked that the canopy was okay; he did not have to pull his reserve.

Seventeen Open Chutes

On Bohannan’s right wing was a C-47 piloted by 1st Lt. Jack B. Olds and 2nd Lt. Robert L. Cloer. They also witnessed Bohannan’s flaming plane. Cloer took the radio microphone and tried to contact Bohannan but, like Perkins, got no answer.

Second Lieutenant Clarence E. Stubblefield, pilot of another nearby C-47, remembered, “I was flying on the left wing of Captain Bohannan’s plane. After we had crossed the coast of Holland about five minutes, a burst of what I thought was machine-gun fire hit Bohannan’s ship underneath, and also my ship. His parapacks burst into flames and in a few seconds his paratroopers started coming out. I could not count all the parachutes, but estimate about 10 or 11. The inside of the ship was burning as well as the outside and Captain Bohannan held his ship in position until all of his troopers that could, had gotten out, and then he dove towards the water [flooded landscape] at about a 45-degree angle.”

Flight Officer Patrick F. McMorrow was copilot in Stubblefield’s plane. He also noticed Bohannan’s plane afire and that the parapacks were dropped. McMorrow watched and counted the parachutes from the ill-fated Bette.

In the airplanes flying behind and beside Bohannan’s stricken C-47, the crew members and paratroopers counted the chutes. Seventeen were seen to open and float down to earth. The 17th chute carried the plane’s crew chief, Thomas Carter, who had followed the paratroopers out. The pilot and copilot were trapped inside the cockpit and could not escape.

Bette, engulfed in flames, was in a dive and with full throttle plowed into a field that had been flooded by the Germans near the Postbaan of the Stadschendijk in the Heiningse Polder, near the farm of A. van Sprang (51o 39’N; 4o 27’E). It was approximately 12:30 pm. The paratroopers believed that the pilots, Bohannan and Felber, had held the plane as long as they could so that the paratroopers were able to get clear. They owed their lives to the men up in the cockpit who had sacrificed theirs.

Arriving at Overasselt

Undaunted by the flaming spectacle, the rest of the serial flew on. In several other planes in the formation, the jumpmasters, as a precaution, ordered their troops to stand up and hook up, although the planes were some 45 minutes away from their drop zones.

Except for the men in Bette, the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment was dropped as planned at Overasselt. As soon as the paratroopers had landed and unhooked their chutes, they gathered themselves into units and dashed off their DZs to fight the Germans. The major objective for the day was the huge and vital nine-span bridge over the Maas River between Grave and Nederasselt. Combat patrols were sent to the Maas-Waal Canal, south of Nijmegen, to capture at least one of the bridges and hold it until the sky soldiers could be relieved by British ground forces.

The 21 planes from the squadron had dropped 295 paratroopers and 105 parapacks on DZ “O.” After the drop at Overasselt, the planes made a sharp 180-degree turn to avoid heavy antiaircraft fire at Nijmegen. The return trip was uneventful, except for some small-arms fire; no plane from the 315th was lost on the way back to England. Only Captain Bohannan’s plane had been lost on the way in, her crew missing or dead. Three other C-47’s from the squadron had received minor battle damage. Several C-47s were forced to make emergency landings at Brussels.

The planes returned to Spanhoe between 3:20 and 3:45 pm. For unknown reasons, two paratroopers were unable to jump and were returned to England. Two other paratroopers had been wounded by shrapnel and could not jump. After the mission, the crews were debriefed. Six crews were alerted for a resupply mission, which was cancelled at 6 pm.

Sending Word of the First Casualties

The following day, pilot Captain Ernest S. Henner noted in his report to the Commanding General, IX Troop Carrier Command: “I was flight leader of the second flight of the third squadron of the first serial on 17 September 1944. After we had crossed the coast of Holland and had gone about 20 miles, I first noticed that Captain Bohannan’s airplane was burning (left engine) and there was a short space of time between which the pilot of the plane released his parapack bundles and tried to extinguish the flames. After that interval, several men were seen to jump from the airplane, which continued to fly straight and level in formation. It continued to do so for about 30 seconds after the last man jumped and then dove into the water at about a 45-degree angle.”

Reports were made by the 315th and other groups and sent to Headquarters IXth Troop Carrier Command full of detailed information about the operation and the losses of airplanes and crews. The U.S. War Department began sending information to the families of the lost, missing, and wounded soldiers. First the families received a telegram with the information that their loved ones were missing over Holland. Then the soldiers’ personal effects were gathered and sent to the Quartermaster Depot at Kansas City, Missouri. From there the belongings were sent to the families.

Survivors of the Bette Touch Down

All that was in the future. On September 17, it was still raining paratroopers from Bette near the town of Heiningen. Pfc. Rideout came down in a flooded field, and Pfc. Leginski landed some 50 yards from him on dry ground. Both men unsnapped their parachutes and started bandaging their wounds. They noticed that the remainder of the stick had also jumped from the plane but had landed on the opposite side of the canal. The two men hid their parachutes and started to move away from the approaching Germans, using irrigation ditches to stay low.

On the other side of the canal, Crew Chief Tom Carter, coming down after his harrowing escape from Bette, noticed water below him except at a crossroads around which were clustered several houses. It was the village of Heiningen. Carter was able to guide his parachute and landed on a roof of one of the houses; Dick Reardon and the other paratroopers splashed down nearby in the water. No one drowned because the water came only slightly above the knees of the men, but they had some trouble freeing themselves from their chutes and harnesses.

Once unencumbered, the men moved toward the houses. They were a sorry sight; the majority of the muddy, sopping-wet paratroopers were wounded or had burns over parts of their bodies and could hardly handle their weapons.

Suddenly, a Dutchman popped up and warned the men to take cover in a deep ditch. The men did so and proceeded along it until they entered one of the houses, where five Dutchmen wearing orange armbands that symbolized that they were in the Dutch Resistance were waiting to help them. The men were Adriaan Nijhoff, Hendrik Nijhoff, Jan van Dis, J. Lanning, and Chris Moerland, a young boy only 14 or 15 years old.

Sergeant Carter had a map in his escape kit and pulled it out. One of the Dutchmen pointed out where they were, some 50 miles short of the intended drop zone at Overasselt. The Dutchmen then informed the troopers that they had to leave but would return soon with other underground members who would guide them to safety.

Realizing that the Germans might arrive at any minute, the paratroopers set up defensive positions in the house. Carter and Reardon took some weapons and moved upstairs while others troopers went into a neighboring house.

“Jerries on the Road!”

A few minutes later, a trooper yelled, “Jerries on the road!” Sure enough, a squad of Germans from the 719th Infantry Division was approaching the houses with weapons at the ready. Soon a firefight broke out. One of the Germans threw a potato-masher stick grenade toward the house, but it missed the window and exploded outside. Another grenade was thrown and exploded inside. Corporal Demont was slightly wounded by shrapnel and also suffered considerable damage to his right ear.

The Germans shouted for the Americans to surrender. Realizing that they were surrounded, wounded, outmanned, and in no shape for a prolonged fight, the men surrendered. They were lined up in front of the houses and searched. The Germans took weapons, watches, rings, and cigarettes from the paratroopers, then marched them to a nearby school.

For the 504th troopers who had escaped the burning Bette, the war was over. Medical attention was given to them by German medics. Lieutenant Rynkiewicz was separated from the enlisted men and interrogated before being evacuated to a hospital. Under armed guard, the prisoners boarded several trucks, and their long journey to Germany began. To give the captives hope, Dutch civilians made V-for-Victory signs as the trucks passed through villages. Once inside Germany a few hours later, the men dismounted from the trucks and were taken inside a building. There they were questioned again.

Several days later the men were loaded into railroad boxcars, and the train started in a northerly direction. The men were afraid that the train might be strafed by Allied fighter planes. Their fears were soon confirmed, but somehow everyone escaped injury.

On another night the train sat in a rail yard while high-flying bombers attacked the yard, dropping their heavy ordnance. Luckily again, no one was hit and the men reached their first destination, Stalag XIIA (Prison Camp #12-A) in Limburg, Germany. Then they were transferred to Stalag III-C near Alt-Drewitz, some 50 miles east of Berlin, where they remained until the spring of 1945 when they were liberated by advancing Russian troops.

As an Air Force soldier, Sergeant Carter was separated from the paratroopers and held in Stalag Luft IV, a POW camp for aviators, in Tychowo, Poland, arriving there in the middle of October 1944. After Christmas 1944, he was moved to Stalag Luft I near Barth on the Baltic Sea in northeastern Germany. The majority of the journey was made on foot. Carter was freed by the Soviets on May 3, 1945.

Leginski and Rideout Meet the Dutch Underground

A different fate awaited Leginski and Rideout. After they reached the outskirts of Heiningen on September 17, they stayed hidden, simultaneously looking for other paratroopers who might be in the neighborhood, avoiding the German staff cars and motorcycles that raced through the town, and searching for a way out of their predicament.

Dusk came, and both men decided to wait for nightfall before going farther. Suddenly, they were alerted by a noise nearby. At first they thought someone was calling for a dog, but then they heard the man say “Oranje,” meaning “orange” in English. Oranje was the code word for the Dutch Underground. Again the Dutchman called out Oranje, and both Leginski and Rideout cautiously approached the man, who they could see was wearing an orange armband.

The Americans, cold and wet, decided to follow the civilian, who carefully entered Heiningen and led them to a barn. There they were given dry clothes, food, and water. Their uniforms and weapons were hidden. Several days later, the men received their uniforms back, cleaned and ironed, and their next adventure began.

They were awakened one morning at 6 am by an English-speaking Dutchman who informed them that the Germans, who suspected that Americans were hiding in the village, were approaching. After getting some cycling instructions, the two paratroopers, in civilian clothes, followed three Dutch Underground members (W. Strange, C. van Andel, and the teenager Chris Moerland) on bicycles. The five men headed for Fijnaart.

The trip took about an hour, and the group passed one German checkpoint en route. The Germans stopped them. The Dutchmen did the talking and apparently satisfied the Germans. The men continued on to the local underground headquarters where they learned the fate of two other troopers. Lieutenant Rynkiewicz and Private Biggs had been taken to a hospital in Willemstad.

Leginski and Rideout asked if someone could take a message to their lieutenant, asking for instructions. A Dutch messenger went to see Rynkiewicz and handed him the note. Rynkiewicz ordered Leginski and Rideout to stay with the Dutch. The two privates would remain hidden in Fijnaart until early November. It was very dangerous since Germans were still in the village.

While this was taking place, the underground members had visited the Bette crash site several times and retrieved weapons, which were then stored in the basement of a carpentry shop. There was a curfew, and no one was allowed to be on the streets after 8:00 pm, but Leginski and Rideout were in need of some fresh air and exercise, so they were smuggled out of town and escorted in a southerly direction.

Returning to the 82nd

On Tuesday, September 19, 1944, several inhabitants of Heiningen (J. Akkermans, Theo Akkermans, B. Lanning, Johan Smits, M. Straasheijm, and Hendrick Nijhoff) obtained permission from the local German commander to go out to the C-47 crash site to retrieve and bury the remains of the four crewmembers killed in the crash. However, the German soldiers in the area had not been informed about the Dutchmen at the airplane and fired on them.

At great risk to himself, Nijhoff waded through the water and approached the Germans to show them their written permission for the burial detail. The Germans kept an eye on this unpleasant task. The four air crewmen were found in the demolished cockpit and were placed in wooden coffins, then taken to the Algemene Begraafplaats (general cemetery) of Dinteloord, where they were buried with military honors. Present at the burial were Nijhoff, Straasheijm, and J. de Visser, the latter the cemetery’s caretaker. Captain Bohannan was laid to rest in grave 19. A cross with the Dutch text, Hier rust een Engels soldaat Richard E. Bohannan 0-789977 (“Here rests an English [sic] soldier”), marked Bohannan’s grave; similar crosses marked the graves of the other men.

During Leginski and Rideout’s southward move, the front lines came closer and British artillery barrages crashed around the group. The barrage finally lifted, and the men encountered British troops and learned that the enemy had left the area several days earlier. Leginski and Rideout helped to take care of the many wounded civilians, said farewell to the Dutchmen who had guided them to Allied lines, then were transported to Antwerp, where both men were debriefed.

The two paratroopers were then taken to Brussels, where they noticed a jeep with “505 PIR” stenciled on the bumpers. The jeep driver agreed to drive both men to Nijmegen where the 82nd Airborne Division was still fighting. They arrived there on November 5, 1944. The remainder of their stick was still carried as missing in action.

Epilogue

As the world knows, Market-Garden was a failure. For the most part, the paratroops achieved their objectives, but their reinforcement was delayed because strong German resistance blocked XXX Corps’ advance. As a result, casualties among the airborne forces were high. On September 27, 10 days after it began, Operation Market-Garden was called off. A long, difficult, and costly slogging match through the Siegfried Line would commence in a few weeks.

In the spring of 1945, soldiers from the 18th Canadian Armoured Regiment, 12th Manitoba Dragoons, arrived in the village of Fijnaart. Mayor Huib Van Dis reported to the Canadians and informed them about the crashes that had occurred in his area the previous September. Members of the underground showed Canadian authorities the location of the crash. The authorities learned that a considerable amount of Dutch currency had been found scattered near the crash site. The money was believed to be the invasion money that had been issued to the crew and had been secured by the Dutch. The money was given to the Canadians, who turned the guilders over to American officials. It was sent to the quartermaster depot along with the inventory of personal effects.

After the war the remains of Bette’s four crew members were exhumed from the cemetery at Dinteloord and taken to the temporary American cemetery at Margraten in southern Holland. Captain Bohannan was buried in grave 3K-10-245, and Lieutenant Felber in grave 3K-10-241. During the correspondence between the government and the families involved, the families informed the government they wanted the remains of their loved ones repatriated to the States.

In December 1948, the remains of Captain Bohannan and Lieutenants Martinson and Felber were exhumed from Margraten, transported to Antwerp harbor, and taken on board the Victory ship USAT Barney Kirschbaum together with many others. At New York harbor the transport ship was unloaded and the coffins were put in a storage facility on Pier 61. From there the coffins were taken by train to the respective hometowns.

Captain Richard E. Bohannan is buried in the Kensico Cemetery at Kensico, Westchester County, New York. Second Lieutenant Douglas Felber was buried on January 31, 1949, in the Camp Butler National Cemetery, located in Springfield, Illinois, in grave C-534. First Lieutenant Bernard P. Martinson was first buried at Margraten in grave 3K-10-242. Today he rests in the Calvary Cemetery in St. Paul, Minnesota.

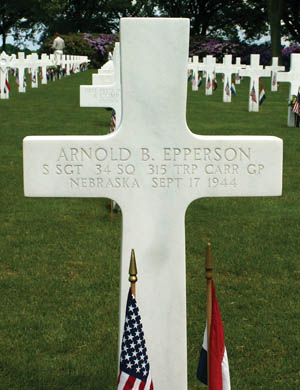

Staff Sergeant Arnold B. Epperson was first buried in the temporary American cemetery at Margraten in grave 3K-10-244. Today, he still rests in Margraten Cemetery but was moved to grave P-3-15.

The sacrifice of the men in the C-47 transport plane Bette, as well as all the Allied soldiers who came and fought to liberate people they did not know, is still remembered by the grateful people of Holland more than six decades after the war.

I also have the story about the crash from the C-47, Bette. Also I have a lot of personal stuff who belongs to the crew / paratroopers, Walter and Everett.

Regards,

Henk.

My Grandfather was Lt. Isadore D. Rynkiewics. On the Bette