By Eric Hammel

A United States naval task force bearing the U.S. 1st Marine Division arrived off Guadalcanal, in the eastern Solomon Islands, on the morning of August 7, 1942, and launched the first American offensive operation of World War II. In only two days, the Marines captured the uncompleted Japanese airfield at Lunga on Guadalcanal, which was the primary target of the invasion, as well as island bastions to the north of and around Tulagi harbor. Japanese air attacks were mounted on August 7 and 8 from Rabaul, 600 miles to the northeast. The Japanese bombers, which damaged a transport and a destroyer, were routed by U.S. Navy fighters from three aircraft carriers that guarded the invasion fleet.

Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa was commander of the newly formed Eighth Fleet, an Imperial Japanese Navy mixed cruiser and destroyer force based at Rabaul. It was his job to defend the Solomons against Allied incursions and to prepare to spearhead a new drive southeastward, toward the New Hebrides.

Fragmentary reports of the battle from Tulagi on August 7—followed by immediate and lasting silence—caused a division of opinion between Admiral Mikawa and his Imperial Army counterpart, Lt. Gen. Harukichi Hyakutake, commander of the newly formed 17th Army, a corps-sized infantry force headquartered in Rabaul but charged with securing New Guinea.

The Imperial Army had no responsibility for events in the Solomon Islands, which were under the control of the Imperial Navy, so perhaps Hyakutake was serving his own interests when he rated the incursion at Tulagi as a mere raid. He refused to provide Admiral Mikawa with troops for an immediate counterblow.

“Wish Your Fleet Success”

Though Mikawa was operating in a virtual information vacuum, he nevertheless divined the enormity of the challenge. At the very least, he reasoned, duty demanded that he strike swiftly and in force. If his estimate of enemy intentions proved to be overblown, little harm would have been done. He ordered every available bluejacket in Rabaul to be armed with infantry weapons and formed into a provisional infantry battalion. In the end, only 410 such troops could be found, and not as many rifles. The minuscule force was sent south aboard a small cargo ship while Mikawa redoubled his efforts to mount a more meaningful response.

An urgent message was dispatched to the Naval General Staff in Tokyo, requesting permission to mount a surface attack on the Allied fleet the following night, August 8.

The Imperial Navy’s chief of staff, Admiral Osami Nagano, considered a night surface attack too audacious; Mikawa had few warships while the Allies seemed to have many, and the transports were certain to be closely guarded. Still, Nagano deferred to Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander in chief of the Combined Fleet, the Navy’s

operational arm. Yamamoto, who was headquartered at Truk, knew Mikawa to be a cautious man and respected his judgment. He radioed his approval: “Wish your fleet success.”

Mikawa, who had been admonished to oversee the foray from Rabaul, boarded his flagship, the heavy cruiser Chokai, on the afternoon of August 7 and ordered the remainder of the Eighth Fleet to stand south through St. George Channel. The force comprised five heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and one fleet destroyer.

The waters were poorly charted, and the going was slow. Though Mikawa and his staff navigator spent long hours poring over the few charts they had at their disposal, the day was lost. Mikawa feared discovery by Allied reconnaissance aircraft, so he decided to remain north of Bougainville until the late afternoon of August 8, when he would steam at all possible speed through St. George Channel, between the double chain of islands—soon to be known as “the Slot”—and launch his attack after rounding Savo, just to the west of the presumed Allied fleet anchorage off Lunga. The Slot, though narrow and restricted, presented the surest means for arriving off Savo at a favorable hour. The risk of discovery was great, but speed was of the essence.

Spotting the Japanese Fleet

Rear Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, the invasion fleet commander, received a message from the north late on the afternoon of August 7: “Two destroyers and three larger ships of unknown type heading [southeast] at high speed eight miles west of Cape St. George.”

The source of the message was an American submarine charged with guarding the waters around the Slot. The boat had had barely enough time to avoid being run down by the Japanese column, much less launch a torpedo attack.

The Eighth Fleet reached Bougainville by dawn on August 8 and launched four float reconnaissance planes to probe the Allied anchorage. The Japanese warships then scattered to confound routine Allied reconnaissance flights in the area.

Chokai was spotted at 10:20 am by a Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) patrol bomber, which circled overhead for a time. Admiral Mikawa reversed course until the Australians left, hopefully convinced that the Japanese cruiser was heading back to Rabaul. Nevertheless, when a second RAAF bomber appeared, Mikawa felt he had little to lose, so he ordered his force to re-form and head through the Slot toward Savo.

In the meantime, one of the Japanese floatplanes returned to report that 18 transports, six cruisers, 19 destroyers, and a battleship were arrayed around Tulagi, Savo, and the northern coast of Guadalcanal. It seemed to Mikawa that he was outnumbered, 26 warships to eight. But the reconnaissance pilot added that the Allied warships were split into three groups, and that gave the Japanese admiral hope that he could destroy at least one battle force before the others could join the fight. The Eighth Fleet steamed on, entering the Slot itself late in the afternoon. The fleet navigator estimated that the cruiser column would arrive off Savo at midnight.

The Eighth Fleet had been formed only a week earlier and had never before operated as a unit, so the simplest of battle plans had to be promulgated. Chokai’s signal lamp blinked Admiral Mikawa’s orders to the other vessels at 4:30 pm: “We will proceed from south of Savo Island and torpedo the enemy main force in front of the Guadalcanal anchorage, after which we will turn toward the Tulagi forward area to shell and torpedo the enemy. We will withdraw north of Savo.” The warships were ordered to stream white sleeves from both wings of their bridges for identification.

Allied Screen at Savo

Minutes before dusk, just as the danger of discovery was nearly past, one of Chokai’s lookouts spotted a masthead to starboard. The fleet sprang to action, sirens wailing, guns tracking the target, which was identified as a friendly seaplane tender bound for New Georgia, a bit farther to starboard.

Just as the Eighth Fleet left the friendly ship astern, Maj. Gen. Alexander Archer Vandegrift, ashore on Red Beach with the main body of his 1st Marine Division, was asked to join Rear Admiral Kelly Turner and Rear Admiral Victor Crutchley, the British commander of the screen warships, aboard Turner’s flagship for urgent consultations.

Only minutes earlier, Turner had heard from Vice Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, the carrier flotilla commander: “Fighter plane strength reduced from 99 to 78. In view of the large number of enemy torpedo planes and bombers in the area, I recommend the immediate withdrawal of my carriers. Request tankers sent forward immediately as fuel is running low.” Fletcher was pulling out even earlier than he had thought he might during the run-up to the invasion.

Though he had no inkling as to its purpose, Admiral Crutchley sensed a note of urgency in Turner’s summons. The giant, red-bearded Briton precipitously ordered his flagship, the heavy cruiser Australia, to leave the screening force south of Savo and follow Guadalcanal’s northern coastline to the main fleet anchorage off Lunga.

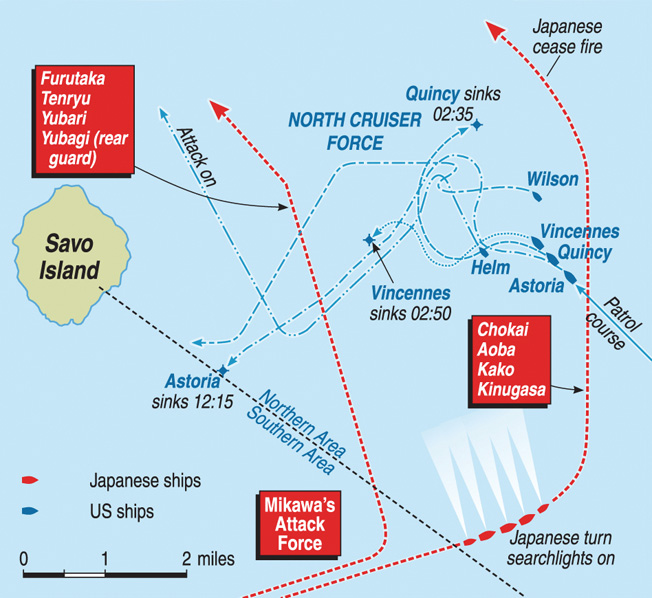

The Allied screen had been informally divided into three groups. Southern Force, with which Australia had been on station, was reduced to two cruisers and two destroyers. Its patrol sector lay between Savo and Cape Esperance at the southern entrance to the channel. Another group, Northern Force, composed of three cruisers and several destroyers, patrolled the northern entrance, between Savo and Florida Island. The third group, Eastern Force, composed of a pair each of light cruisers and destroyers, patrolled the eastern extremity of the anchorage. Crutchley exercised direct tactical control over all three groups and had designated no subordinate commanders.

His departure without word to Northern or Eastern Forces left two-thirds of his command leaderless to all practical purposes. He did inform his senior Southern Force captain that he was leaving, but did not actually leave the man in control. That officer did not even think to move his own heavy cruiser, Chicago, to the head of the patrol column, as convention dictated, nor did he inform any of the other captains. Captain Frederick Reifkohl, whose heavy cruiser Vincennes was in Northern Force and who was senior captain in the screening force, should have been left with the overall command, but he did not even know that Crutchley had left the patrol area with the flagship. The cruiser screen was left leaderless and without a plan.

Interpreting the Japanese Fleet’s Actions

Turner’s meeting was late getting started. Crutchley had pulled Australia out of the screen in haste, but it still took two hours of poking around in the gloom for him to find Turner’s flagship, the transport McCawley. General Vandegrift embarked in a small boat and did not find the flagship until 11 pm.

While waiting for Vandegrift, Turner and Crutchley discussed a message that had just been relayed from the air base at Milne Bay, New Guinea: An RAAF aircrew had spotted a Japanese naval force heading southeast from northern Bougainville. The message had arrived following an eight-hour delay because the pilot had waited to land before making his report. The message indicated that the Japanese force was composed of three cruisers, three destroyers, and a pair of seaplane tenders.The admirals agreed that the presence of the tenders might indicate a morning air attack. The fact that only three cruisers had been sighted was reassuring; the Japanese would not dream of launching a surface attack, particularly at night, with a force of only three escorted cruisers.

Turner knew that the Japanese would feel obliged to make some sort of gesture against his fleet, and he suspected that the Slot would be used to make an approach. Accordingly, he had requested a Navy long-range patrol bomber to search the channel that day. There was, as yet, no report, which the admirals took to be a good omen. In fact, the mission had not been undertaken.

When Vandegrift entered Turner’s compartment, he noted that the two admirals seemed about to pass out from the oppressive heat. He accepted Turner’s offer of a cup of coffee, then sat down to hear the bad news.

Turner told him of Fletcher’s decision to leave early. Vandegrift grew livid; the carrier force commander had earlier promised to give him at least 12 hours to unload the transports––more than he now proposed. Even then, Vandegrift had had no hope of getting his division’s supplies ashore. Turner repeated the news about the seaplane tenders and indicated that, lacking air cover, he too was obliged to retire at dawn; his transports were highly vulnerable to air attack.

Turner, the amphibious force commander, asked the Marine division commander for his opinion, and the general replied that the 1st Marine Division was in fair shape on Guadalcanal; he doubted that Tulagi could be adequately defended, though he admitted having no direct knowledge in that regard. Turner nodded and mentioned that he had foreseen the response, and that a fast minesweeper was standing by to carry Vandegrift to Tulagi.

Crutchley offered to take the general to the minesweeper on his way back to Australia. Vandegrift declined, but the Briton insisted: “Your mission is much more important than mine.” The two boarded Crutchley’s gig minutes before midnight. A heavy rain squall was blustering to port, separating the Northern and Southern Forces. To starboard, a red glow marked the spot where the transport Elliott, the victim of an aerial bomb, lay grounded and burning. As Vandegrift mounted the minesweeper’s ladder, Crutchley shook his hand and said that he knew what losing the fleet meant to the Marines. “I don’t know as I can blame Turner for what he’s doing,” said the British admiral.

The Blind Allied Picket

Gunichi Mikawa was moving in for the kill. The Japanese had any number of advantages, not the least being their ability to control events. But they lacked radar, and that, Mikawa feared, might be their undoing.

Rigorously selected and keenly trained lookouts, the finest in any navy, were capable of spotting mere shadows at eight miles, and they were equipped with the finest night binoculars in the world. In addition, three three-place spotter planes had been launched to track the Allied fleet. When Mikawa engaged Southern Force, they were to launch parachute flares to assist Japanese gun crews.

American picket destroyers near Savo heard the sound of aircraft engines as the Japanese floatplanes traversed the anchorage. Several duty officers queried higher authorities, and several issued warnings. A few did nothing. It was finally agreed that the aircraft were Fletcher’s, though no one could explain what carrier aircraft might be doing over Savo in the dead of night, nor why no one had been told to expect them.

It was 11:45 pm. Admiral Crutchley was unavailable, somewhere amid the shipping, ferrying Archer Vandegrift to the minesweeper. Australia was routinely notified of the aircraft contact, but no one aboard felt compelled to take charge.

The Eighth Fleet was approaching Savo at 10 minutes after midnight. The conical island was ahead to port and Cape Esperance loomed to starboard when lookouts spotted a low form moving dead ahead. Gun crews swung out their batteries to cover the dark silhouette; 50 naval rifles were brought to bear in a trice.

Blue, an aging picket destroyer, routinely changed course at 12:40 am from roughly northeast to roughly southwest, maintaining her speed at 12 knots. Visibility was good. No unusual contacts had been made by radio, radar, sonar, or sight since 11:45. The crew was at General Quarters, the highest state of alert. Lookouts had been concentrating on navigation landmarks to the east for several minutes before and during the turn, which happened to be away from the path of the Eighth Fleet. Blue made no movement of recognition and continued blithely on her way. It was 12:43 am.

Blue’s failure to react worried the Japanese admiral nearly to distraction. He had no idea what the American skipper’s game might be, though it was easy to imagine him trying to bluff his way out of certain destruction while filling the airwaves with alarms. Mikawa chose to assume that he had not been sighted. To make certain, he dispatched his lone destroyer, Yunagi, to keep tabs on the seemingly blind picket. Ironically, Blue had been moving toward the projected Japanese track from 12:10 to 12:40 am. Even more ironic is the fact that Ralph Talbot, the picket destroyer north of Savo, also had her stern to the Japanese warships as they squeezed through the passage.

Japanese lookouts perched in the masts poured down a torrent of data to fire control stations as their ships approached the Allied force. Mikawa ordered speed increased to 26 knots and released his captains to commence independent firing at any time. Torpedoes hissed into the water an instant later.

It was now 1:36. Southern Force had been firmly fixed, coming up from the southeast.

“Warning! Warning! Strange Ships Entering Harbor.”

At 1:43, just as the Japanese spotter aircraft were preparing to release their flares, lookouts aboard the destroyer Patterson sighted a shadow in their ship’s path. “Warning! Warning! Strange ships entering harbor.”

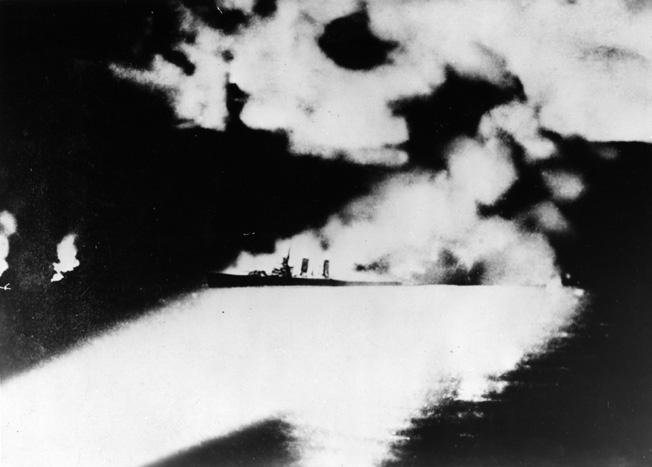

It was an instant late. The parachute flares blossoming overhead silhouetted Chicago in Japanese gunsights. Then the Australian cruiser Canberra appeared. Chokai, only 4,500 yards distant, opened with her main batteries, Aoba fired from 5,500 yards, and Furutaka opened from 9,000 yards.

Before Canberra’s crew even spotted the enemy, before the Australians could train out their guns, Japanese torpedoes had blasted a great hole in the side of their ship, followed closely by the first 4.7- and 8-inch salvoes. Canberra’s captain fell, mortally wounded. The ship’s gunnery officer died in the first blast, along with many of his shipmates. Canberra launched two torpedoes and got off a few 4.7-inch rounds. Then she was out of the fight, her power out, dead in the water.

Patterson surged after the enemy cruiser column while Japanese gunners put out a few disdainful salvoes in her direction. The after-gun mount was hit, and ready ammunition and powder exploded and burned. Patterson came on, firing at the tail cruiser Yubari. Suddenly it was quiet. The Japanese were beyond sight. Patterson’s torpedoes were still in their tubes despite the captain’s order to launch them.

Destroyer Bagley was up next, but she had no luck. The spread of torpedoes she launched sped off uselessly to the north.

Chicago got off easier than Canberra by pure chance and because her lookouts had seen orange flashes at 1:42 am—the Japanese launching torpedoes—and aircraft flares over the transports a minute later. Canberra’s sudden wheel to starboard from dead ahead clinched the matter. Lookouts passed word that two shadows were in sight nearby. The captain, who was just awakening from a nap, ordered his 5-inch secondary batteries to prepare to illuminate with star shells. A lookout spotted a torpedo wake to starboard at 1:46, and Chicago was hit a minute later, her bow blown clear off. Gunners staggered under the impact, then fired star shells in an effort to pinpoint a target—any target. The damaged cruiser tried for two minutes to range in on a pair of mysterious lighted targets ahead. One must have been the destroyer Yunagi, which Admiral Mikawa had detached to look after Blue. The second target might have been Jarvis, a destroyer damaged by a Japanese aerial torpedo that afternoon.

Preoccupied with licking their own wounds or coming to the aid of cripples, no one in Southern Force thought to issue an alert. The Japanese had sustained zero damage in the course of crippling a pair of cruisers and a destroyer.

Admiral Mikawa was already on the scent of the Northern Force cruisers, which were maintaining a boxlike patrol pattern north and east of Savo. American lookouts had no idea that a battle had been fought to the south because Savo’s silhouette and a line of squalls between the two Allied forces obscured the view.

Hitting the Northern Force

On glimpsing Northern Force through a break in the squall line, Mikawa ordered a course shift to east-northeast at 1:44 am.

Chokai, in the van, made the prescribed move, as did the three heavy cruisers immediately astern. But Furutaka, the last of the heavies, found herself on a collision course with the cruiser ahead and veered to port, her bow aimed directly at the American cruiser line to the north. She settled on a more northerly heading at 1:47, the two light cruisers in her wake. By pure chance, the two Japanese columns were on parallel courses with the Northern Force column between them.

Patterson’s voice-radio warning at 1:43 and the string of parachute flares to the south had alerted Northern Force to danger, but no one knew from where it might emerge nor, in fact, that it was approaching at all. Without hard facts, the line of cruisers maintained its 10-knot patrol speed, the helmsmen taking care to turn a square corner to the northeast at the end of the southwestern leg of the box.

Tenryu’s lookouts spotted the American column at 1:46, just as their ship was turning to follow Furutaka to form the inadvertent second column. Word was flashed two minutes later to Admiral Mikawa, who ordered torpedoes launched immediately; 17 were away within moments. The Eighth Fleet majestically charged against the unknowing Americans, batteries swiftly swinging outboard to track targets.

Astoria, at the tail of the American column, was maintaining a routine watch. Her skipper, Captain William Greenman, was sleeping off the accumulated strain of two days on the conn. The officer of the deck, Lt. Cmdr. Jim Topper, noted slight tremors from the south, but assumed that destroyermen were relieving their anxieties by dropping depth charges on phantom submarines. The tremors were Chokai’s torpedoes harmlessly detonating after missing Chicago.

A lookout reported seeing a star shell far to port, and Jim Topper looked up in time to see a string of aircraft flares. Someone else pointed to a searchlight beam (Chokai’s) at 1:50. That did it! Topper called Astoria’s crew to General Quarters only a minute before a shell exploded just off her bow.

The main-battery spotter announced that three enemy cruisers were off the port quarter and closing, but it was 90 seconds before Astoria’s 8-inch guns could be trained out to port and fired at Chokai.

As Lt. Cmdr. Topper was passing the order to commence firing, Captain Greenman, who had been routed out of his bunk moments earlier, stepped onto the control bridge and hurriedly assessed events to that moment. “Topper,” he cautioned, “I think we’re firing on our own ships. Let’s not get excited and act too hasty. Cease firing.”

The ship’s gunnery officer remained convinced that the targets were hostile; he pleaded to be allowed to resume firing. Captain Greenman assented at 1:54.

Meanwhile, Chokai had had time to fire four full salvoes at Astoria, but none had yet scored. The misses might have given the American gunners time to strike back, but the debate on Astoria’s bridge and the cease-fire order benefited the Japanese flagship. The fifth 8-inch salvo then ripped through the American cruiser’s superstructure, and Astoria’s midships section burst into flames. Chokai blazed away as Captain Greenman firmly ordered all his guns into action.

It was too late for Astoria. Her communications had been destroyed, and her deck was disintegrating under the impact of repeated hits. The gun crews were severely hampered by the heat and smoke of fires; in all, Astoria managed to get off 11 partial 8-inch salvoes. Captain Greenman had to order an abrupt course correction to avoid ramming Quincy, which was in line dead ahead. The move was unfortunate, for it brought Greenman’s ship between Quincy and more menacing Japanese batteries.

Then the worst blow of all fell: A shell burst directly on Astoria’s bridge, cutting down most of the bridge watch. The helmsman managed to regain his feet and bring the cripple back on course to the northwest, but scores of sailors below decks were felled by searing flames, billowing smoke, and superheated steam. The cruiser slowed to barely seven knots. Fires were raging down her entire length, but her crew continued to fight; Turret 2’s last salvo caught Chokai’s forward turret. But then Astoria was left behind.

USS Quincy: First Ship Sent to the Ironbottom Sound

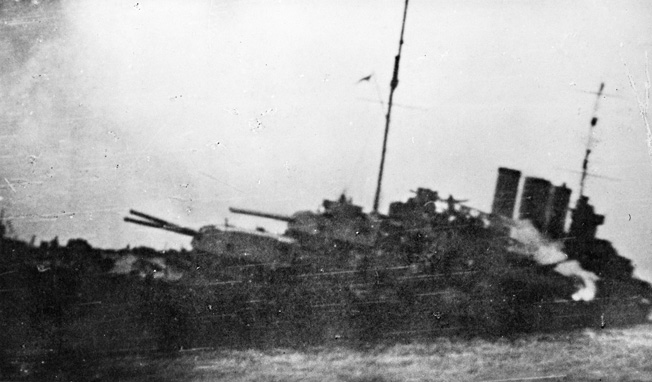

Quincy was already getting hit. The watch had had warnings and hints identical to those registered aboard Astoria, but they too had helped little. On receiving Patterson’s warning, the officer of the deck had called Captain Samuel Moore from his emergency cabin, abaft the bridge, where he was resting. Just as Moore appeared on the bridge, the second cruiser in the Japanese starboard column, Aoba, fixed his ship in her main searchlight battery and pumped several rounds into the water beside Quincy’s bow. Moore ordered his gunners to “fire at the ships with the searchlights on.”

When the guns did not bear on the targets quickly enough, Moore again ordered, “Fire the main battery!” But nothing happened for long seconds, though the cruiser’s 5-inchers had been trained out for minutes. “Hurry up,” the captain fumed. “What’s taking so long?” Immediately, a full nine-gun salvo was loosed. “Full speed ahead,” Moore ordered.

After the second salvo, Moore decided that he was firing on friendly ships, so he ordered recognition signals lighted.

Quincy’s officer of the deck felt that the ship was on a collision course with Vincennes, dead ahead, so he ordered course shifted slightly to starboard, a move that masked the forward guns.

Quincy was then struck in the stern aircraft hangar, and the volatile contents of the structure erupted in a furious blaze. The captain ordered the burning observation plane to be pushed over the side, but crewmen could not get close enough.

“Hard a-starboard,” Moore ordered. The ship turned directly into the beam of a Japanese searchlight.

“Fire at the searchlight!”

Turret 1 traversed and fired, and the Japanese ship went dark.

Lighted better than she could have been by searchlights, Quincy caught numerous rounds from both Japanese columns. The next incoming salvo was 100 yards short, and the next was 75 yards over. Everyone on the bridge pulled in their heads; they knew a straddle when they saw one. Nearly all the starboard 5-inch gun crewmen were felled by the next salvo. Two torpedoes struck the port bow and breached the forward magazine, which blew up.

Moments after Turret 2 received a direct hit and exploded, Captain Moore encouraged his surviving gunners to “Give ‘em hell,” then was felled by a direct hit on the pilothouse, which took out most of the bridge watch.

The galley was ablaze, as were all the boats on the boat deck, the hangar area, the well deck, and the fantail. The ship was listing to port. A Japanese cruiser passed by at high speed, about 200 yards to port, and pumped salvo after salvo into the cripple. One of Quincy’s firerooms was opened to the sea by a torpedo, and communications to that point were lost, dooming the black gang, which was sealed off. A 5-inch gun was destroyed when another hit sparked its ready ammunition.

Captain Moore said with his dying breath, “Beach the ship.” The bridge phone talker, a lieutenant commander, staggered out of the pilothouse and mumbled through a face that had been half shot away, “Everything will be okay. The ship will go down fighting.”

Quincy’s senior surviving officer made his way to the bridge, where, stunned by the carnage, he immediately ordered, “Abandon ship!” The survivors made it into the water by the slimmest of margins. At 2:35 am, the heavy cruiser capsized to port, twisted furiously, and slid away beneath the waves—the first of numerous warships to inhabit the floor of what would soon be called Ironbottom Sound.

Vincennes Set Alight

The leading Northern Force cruiser—the last the Japanese overtook—was Vincennes, and she had had more warning than her dying sisters. Captain Frederick Reifkohl was awakened after the deck watch first spotted flares and after men on deck felt two distinct underwater explosions and spotted flashes of gunfire away to the south. Reifkohl felt that Chicago, Canberra, Australia, and their escorts were firing on aircraft. He ordered speed increased to 15 knots.

Aviation Machinist’s Mate 3rd Class William “Rusty” Campbell, a member of the port aft 20mm gun crew, distinctly saw illumination burst over Astoria, then saw Japanese shells strike the trailing cruiser from the waterline to the bridge. Fires flared and died.

A Japanese cruiser abaft the port beam illuminated Vincennes at 1:50, but Captain Reifkohl thought that the lights were those of Southern Force and sent an urgent radio appeal for the lights to be doused. Nevertheless, the gunnery officer ordered his guns trained out to port to track the nearest silhouette.

Rusty Campbell spoke rapidly into the sound-powered phone resting on his chest, asking permission to open with his aft 20mm gun to try to douse the lights. Permission to fire was denied because, a disembodied voice said in his ear, “They might be our friends out there.”

The 8-inchers and most of the lighter weapons were tracking targets, but Kako, the third cruiser in the eastern Japanese column, got off the first rounds. A violent explosion engulfed Vincennes well forward on the port side. Rusty Campbell’s sound-powered phone went dead.

Vincennes’ 8-inchers returned fire at 1:53 over a distance of five miles. Their second salvo hit the last of the Japanese eastern cruisers, Kinugasa, but incoming struck Battle 2, the secondary command center, right over Campbell’s head.

Campbell slipped out of his harness and crouched behind his gun’s splinter shield. Another salvo hurtled him over the splinter shield and onto the deck, burying him under a pile of 20mm ammunition cans. A helping hand pulled the temporarily blinded gunner from beneath the cans.

The Japanese had succeeded in setting the American cruiser’s aircraft hangar aflame, so they switched off their searchlights and fired at the burning target.

Campbell regained his sight as he was crawling inboard past the motor launches. A chief petty officer grabbed him and ordered him to run out some hose to try to fight the fire raging around the spotter plane on the port catapult, Campbell’s primary work station. Campbell did as he was told, clamping the hose to the nearest hydrant on the boat deck and turning the valve. All he got was an ample shot of live steam.

The deck was growing hot beneath Campbell’s feet, so he was only too glad to obey instructions to get down to the fantail; a storage locker only 10 feet beneath Campbell’s gun was filled with bombs and depth charges, and Campbell wanted to be as far away as he could get from that blast when it occurred.

As Captain Reifkohl ordered a turn to port so he could close on the Japanese, a hit on the port side of the bridge cut down many of the men standing around him, but Reifkohl remained on his feet, untouched. All around, guns were being demolished and communications throughout the ship were disrupted as more of the Japanese cruisers found the range. Vincennes’ main battery fire had to be maintained under local control.

Reifkohl next ordered a starboard turn to bring his ship out of the crossfire. Just then, however, several of Chokai’s torpedoes exploded on the port side by Fireroom 4.

“We’d Better Get Our Asses Out of Here”

It was 1:55, and Vincennes was doomed. One fireroom was off line, its crew smothered to a man. A torpedo from Yubari, in the western Japanese column, burst beside a starboard fireroom at 2:03, killing the entire complement.

Emerging from the cover of the starboard aft 20mm gun, Rusty Campbell and the gunners around him peeked down at the well deck, where they saw the port 5-inch batteries and the bridge take repeated hits. There were fires everywhere. Campbell shouted down to a shipmate to learn what was going on, and the man shouted back that “Abandon ship” had been passed. In fact, though the cruiser was slowly losing way and listing heavily to port, Captain Reifkohl was only just beginning to think about ordering the crew into the water.

Campbell felt it was time to make a decision. He told the two gun crews, “We’d better get our asses out of here.”

Twenty frightened sailors moved for the ladder at the same instant, jostling one another for position, dropping heavily to the deck below. They had to pass through the main superstructure aft, down three decks in all, to get to the fantail, from which they could enter the water. The ship’s power was gone, so it was stone dark inside. Shells burst through the port bulkhead, sending everyone sprawling to the deck in a great heap. Campbell fell face up, another man’s shoes in his face. He saw holes appear in both bulkheads as another shell went right through the compartment without detonating. There was a good deal of shouting. A third shell exploded when it hit the starboard bulkhead. The man on top of Campbell went limp while Rusty took a piece of shrapnel in the foot.

The roiling mass of men slowly sorted itself out and dribbled down the ladder to the next deck, where a secured manhole cover barred the way; it seemed to take ages before eager hands undogged the hatch. Campbell was the first man through, and he was terrorized. It was pitch dark, so he could not see if a hatch directly beneath his feet was open. If it was, Campbell could plunge 20 feet to a steel deck. If not, the drop was a few inches. He hung for long moments by his fingertips, until a pair of feet hit him in the head, and he plunged into the abyss. The fall was a four-incher. Campbell shouted to the men above that it was safe to come ahead.

A dilemma arose. Campbell’s berthing space was directly beneath his feet. He pondered the merits of making a quick side trip to winkle out the $60 in cash he had hidden among his skivvies and the new $55 gabardine dress blues he had worn only twice. Suddenly, the connecting hatch opened and ammunition handlers from below boiled toward the adjacent fantail. Rusty followed them into the open, wondering at his stupidity.

Campbell stepped onto the fantail and walked forward until stopped by thick flames and smoke. He turned back aft just as Japanese shells hit the bulkhead over his head. He ran. Another shell sent a piece of shrapnel into his left leg and hit the kapok life jacket covering his stomach so hard he doubled over. He smelled something burning, reached down to where he had been hit, and scorched his fingers on a white-hot piece of shrapnel embedded in the life jacket.

The firing abruptly stopped at 2:15 am.

Only the destroyer Ralph Talbot stood between the Eighth Fleet and freedom, and her skipper ordered her in after the Japanese. Furutaka, Tenryu, and Yubari, the western Japanese column, fired a total of seven salvoes at the oncoming American destroyer, but she was hit only once, in the torpedo tubes. Then Yubari fired one last time, holing Ralph Talbot’s charthouse, knocking out part of the automatic gun-control system, and striking a 5-inch mount. The destroyer countered with an unsuccessful four-torpedo spread and ended the fight by entering a rain squall near Savo.

Ensign Paul “Tuny” Moffat, a destroyer squadron supply officer, was asleep in his stateroom aboard Ellett, a new destroyer and one of the fastest in the U.S. fleet, when he was awakened by the General Quarters klaxon. Moffat could hear the sound of gunfire from the west and could feel the ship storm away from its station off Tulagi. When Moffat came topside and headed for his battle station, the forward machine-gun battery, he could see flashes of gunfire to the west. By then, Ellett was steaming toward the battle at full speed.

By the time Ellett arrived off Savo, the Japanese were gone. Though mindful that his primary mission was getting at the transports, Admiral Mikawa elected to forgo his advantage because he expected the American carriers to mount search-and-strike missions before dawn. He need not have worried, for Fletcher’s task force had already steamed out of range. The foray had been a clear victory, but the Japanese warships had seriously depleted their magazines, and Mikawa was convinced that he had tackled a far larger battle force than the Allies actually had in the vicinity. He chose discretion and left.

Ellett’s captain, Lt. Cmdr. Francis Gardner, conned his ship directly to the aid of Quincy and Vincennes, which were aflame and in imminent danger of sinking. When Gardner heard cries for help from the water, he took an unprecedented and incredibly dangerous step. At his order, Ellett went dead in the water, fully illuminated by the burning cruisers. Rescue operations immediately commenced.

Abandoning the Vincennes

Ensign Tuny Moffat was the first man into the water, the one who tested rumors about schools of predatory sharks being loose in the channel. There were no sharks, but there were more castaways than Moffat could begin to help. He got a firm grip on one swimmer and helped him back to Ellett, at which point he was ordered to reboard because he was not secured to the ship with a lifeline, as were dozens of other destroyermen who had followed him into the inky water.

Vincennes was listing heavily to port, and there was a wide divergence of thought on the subject of abandoning ship. Some gunners had remained at their stations with secondary batteries, but crewmen were also drifting astern in life rafts. As Rusty Campbell stood by the rail—trying to make up his mind, watching seawater reach the port scuppers—he reached into his pocket, pulled out a cigarette, and lit up. He had taken only a few drags when a young officer snarled from by his elbow, “Sailor, put that cigarette out! Don’t you know the smoking lamp is out?” The seaman stared at the officer in disbelief. Vincennes was aflame from stem to stern, and here was a character who was worried about a burning cigarette. Shock deepened when the officer repeated his order: “You heard what I said! Put that cigarette out!” Campbell flipped the butt into the water and glared back at the officer, convinced the man was about to ask for his name, rate, and service number.

Then it was time to go. Campbell took off his shoes and placed them neatly in line with 40 or 50 other pairs, then stepped off the deck into the water and swam about a hundred feet to the nearest raft. A strange sound behind Campbell brought him around. He floated on his back just in time to see Vincennes roll over, her four screws right on the surface. People were standing on her keel, between the screws. She hung there for a few minutes, then gently slid beneath the light swell.

Twenty-year-old Rusty Campbell, who had been at home aboard Vincennes since before the war, felt warm tears in his eyes as he pulled for a nearby raft and was helped out of the water.

Hundreds of refugees boarded Ellett and moved into every available space below decks to receive medical care or rest. A bluejacket whose lower jaw had been shot away died in Ensign Moffat’s bunk. Moffat was sickened when the open deck behind his machine-gun battery was used to store the dead, who were neatly stacked—like cordwood—to conserve space.

Quincy and Vincennes went down during the night. Canberra’s crew fought to extinguish the flames that were ravaging the ship, but the Australian cruiser was too badly mauled for quick salvage. A message from Rear Admiral Kelly Turner clinched her fate; she was to be scuttled if she could not retire with the fleet at 6:30 am. Her executive officer reluctantly ordered his crew to abandon ship, and hundreds of pajama-clad Aussies transferred to the destroyer Patterson, where spare clothing was broken out of the crew’s lockers and unselfishly passed around. Blue moved to assist Canberra’s crew at 6 am, and she and Patterson took off the last of 608 Australian officers and sailors shortly after 6:15.

Tuny Moffat watched from Ellett as a dark form loomed out of the semidarkness several thousand yards out. Was a Japanese cruiser returning to sink rescue vessels? Moffat watched and waited as the barrel of Ellett’s forward 5-inch gun depressed and tracked the target. Shell after shell was pumped into the silhouette, frightening men in the water and aboard Ellett. The target was Canberra! Unbeknown to Moffat, Ellett had been ordered to scuttle the Australian cruiser with gunfire, but could not. Canberra did not sink until torpedoed by another destroyer at 8 am.

Meanwhile, Chicago’s befuddled captain was looking for game, and he settled on Patterson in the half light of the new day. Luckily, no hits were scored before Chicago ceased firing.

Astoria was still afloat, and her crew wanted her to stay that way. Prodigious efforts by Captain Greenman and 300 volunteers who reboarded her following rescue proved fruitless. A minesweeper tried to pass a tow, but that effort failed and a cargo ship finally came alongside to evacuate the salvage crew. Astoria heeled over to port at 12:35 pm and sank.

Hundreds of men remained in the water for hours. Shortly after crawling aboard a life raft, Rusty Campbell went back over the side to make room for an injured man. Somehow, he wound up alone and adrift on the wide sea, fearful that his limited prowess as a swimmer would kill him. He was treading water, getting panicky, when something nudged him in the side. A shark? No. It was an empty 5-inch powder can, which he grabbed for dear life. Minutes later, several more powder cans floated by, and Campbell put one apiece beneath each armpit and behind his knees. Out of the darkness came the sound of singing. It was a shipmate, who was repeating the lyric of a popular song: “Hold tight, hold tight. I want some seafood, Mama.” The two exchanged tales and scuttlebutt, then drifted apart. The tide carried Campbell toward the burning and grounded transport Elliott.

In time, Campbell saw ships stopping to take on survivors. His prayers seemed about to be answered when he saw a destroyer (Ellett) heading right for him. She was only a hundred yards away when she began to drop depth charges at an imagined submarine in the channel. The concussion nearly bilged Rusty, but he desperately clung to his ammunition cans until another destroyer, Helm, came up beside him. Campbell was dragged to the deck, where he asked the time. It was 9 am. His watch had stopped when he went into the water; it read 2:40 am.

The unprecedented loss of four first-line cruisers in a single action in which the enemy had been but superficially damaged was catastrophic. The defeat was mitigated somewhat on August 10 when an American submarine put a pair of torpedoes into Kako’s hull and left her sinking off New Ireland. That put the score in the Solomons at four heavy cruisers and one transport sunk and one destroyer (Jarvis) missing to one Japanese heavy cruiser sunk.

Kelly Turner’s amphibious force and its surviving escorts retired early in the morning, as promised. It carried in its holds a vast amount of equipment and stores belonging to the 1st Marine Division.

The Impact of the Defeat at Savo

The Savo Island naval battle had profound influences on the early and middle parts of the six-month American-run campaign to permanently secure a solid forward base for future offensive operations at Guadalcanal. It largely erased the headier effects of the massive, morale-restoring victory at Midway; it rendered the American surface navy timid, a timidity that all but starved the nascent Guadalcanal battle of food, troops, and weapons. It cast a pall on every aspect of the fighting well into October and probably forestalled a victory that could not be assured until halfway into November 1942.

At a single stroke at Savo, a relatively small Imperial Navy surface battle force seized the initiative, gave the U.S. Navy its worst defeat, and set the terms for months of campaigning that involved all that the naval and air forces of both sides could bring to bear. By brilliantly guiding his operationally outnumbered cruisers to victories over tactically outnumbered Allied battle componants, Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa came as close to defeating the offensive war plans of the U.S. Navy as the Japanese carrier force had done at Pearl Harbor.

This website continues an error relating to the warning from the RAAF Hudson reconnaissance aircraft, who did in fact transmit a warning at 10.26 am which Read:

3 cruisers, 3 destroyers, 2 seaplane tenders or gunboats. Lat 0459-S, Long 156-07 E. Course120 degrees, Speed 15 knots. The message was not acknowledged and at 12.42 they landed at Milne Bay to discover that communications had been disrupted by a storm. The message was then forwarded immediately to Pt Morseby. It appears that it was then sent on to GHQ SWPA who apparently did not realise its importance (the report would show the Japanese force leaving the SWPA AO). At 6.45 pm the message reached Turner, but it was too late to launch a air strike from Fletcher’s carriers. (Confirmation of the RAAF sending the report was received in 1984 when the bridge log of the Chokai covering this operation, was discovered in Tokyo and found to be a word for word copy of the RAAF signal. in 2014 the US Navy History and Heritage Command wrote to Eric Geddes, the radio operator of the first RAAF Hudson to say they accepted his version of events as accurate.)

The mistaken identity of two cruisers for seaplane tenders can be understood by reference to Jane’s Fighting Ships photographs and identification diagrams which show all but Chokai among the Japanese heavy cruiser having and extended superstructure near the aft funnel with a catapult and crane. his might have lead the submarine and aircraft to think this was a hangar structure. It should also be noted that Jane’s and other such contemporary publications had limited reliable information on Japanese warships from the late 1930’s.

One of the results of this battle was a decision by the Marines to take their own planes with them on future operations. They felt they could not rely on the Navy after Fletcher’s departure with the carriers before the start of the battle despite the known possibility of Japanese presence in the area. Eventually, Marine aviation units were assigned to support ground operations in many areas. One of the best known was VMF 214, led by “Pappy” Boyington, who racked up a total of 28 kills in the air.

Thank you for this sad story of complacency, incompetence, poor leadership and poor communication that plagued The US Navy in the early part of the war. It is testimony to American luck that this battle’s consequences and the outcomes of other nearby engagements through the end of 1942 did not bring catastrophe to the Marines on Guadalcanal. On the other hand Mizawa’s decision not to aggressively exploit his hard-won advantage would be repeated by Japanese naval leadership throughout the war, most notably in the Battle Off Samar in October 1944–more good luck for us.

My uncle Edward J Batten, Fireman 3rd, was KIA, aboard the USS Quincy, he was 19 years old. My grandmother gave him permission to join the Navy at age 17, my Mom said he really had no interest in school.