By Melanie Savage

On the morning of October 17, 1859, an aide to Secretary of War John B. Floyd hurried off with an urgent message for Colonel Robert E. Lee. Floyd had just received word that the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, had been seized by a group of antislavery zealots led by the notorious terrorist John Brown. Floyd was ordering Lee to come to Washington (he was on leave at his home in Arlington, just across the Potomac River) and take command of the force being sent to Harpers Ferry to retake the arsenal and restore order to the community. Also home on leave that morning was a young cavalry officer from Virginia, 1st Lt. James Ewell Brown Stuart, nicknamed “Jeb,” who had been waiting for some time to see Floyd. The aide convinced Stuart instead to ride over to Lee’s home and deliver the peremptory orders. Floyd needed to scrape together a body of soldiers for Lee to lead to Harpers Ferry, a daunting task since no Army troops were readily available. President James Buchanan, normally a procrastinator, immediately realized the seriousness of the situation and demanded quick action. Secretary of the Navy Isaac Toucey jumped at the chance to get involved, telling his chief clerk, Charles W. Welsh, to ride over to the Washington Navy Yard and see how many Marines in the Civil War could be mustered for duty. Upon arrival, Welsh spoke with 1st Lt. Israel Greene, temporarily in charge of the Marine barracks. Welsh told the young Marine officer what had transpired at Harpers Ferry and directed him to gather as many men as he could for duty.

Although Greene was the senior line officer present, Major William Russell, the Marine Corps paymaster, accompanied the detachment of 86 leathernecks. Working with the major, Greene saw to it that each of the 86 men drew a full complement of muskets, ball cartridges, and rations. Since no one knew for certain the strength or exact position of the insurgents, two 3-inch howitzers and a number of shrapnel shells were also made ready. At 3:30 pm, Greene and his Marines set off by train to Harpers Ferry. At 10 that evening, Lee and Stuart linked up with Russell and Greene at Sandy Hook, Maryland, just across the Potomac from Harpers Ferry.

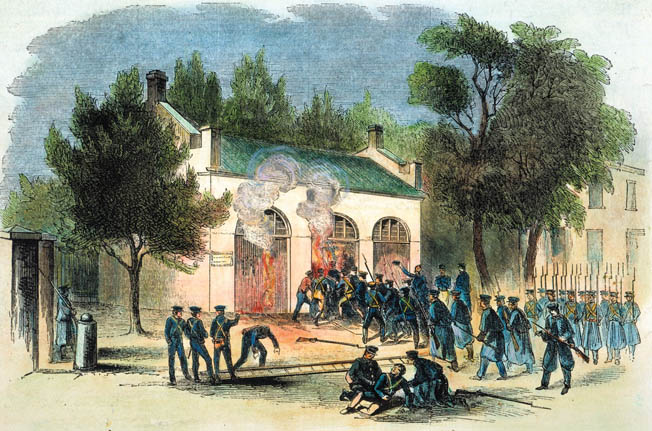

After a botched attempt at taking over the town and inciting a slave rebellion, Brown and his polyglot force had seized hostages and taken refuge inside a small brick engine house on federal property. The Marines marched to Harpers Ferry, entering the arsenal grounds through a back gate. About 11 pm, Lee ordered the various volunteer units out of the grounds, clearing space for the only regular troops at his disposal—the Marines under Greene.

The following morning, Lee demanded that the terrorists surrender. When all attempts to negotiate with Brown failed, 27 Marines broke down the door with a battering ram, rushed into the building, killed or wounded the holdouts, and took Brown prisoner. Lee would later write, “I must also ask to express my entire commendation of the conduct of the detachment of Marines, who were at all times ready and prompt in the execution of any duty.”

Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry and his subsequent execution added fuel to the already simmering political fire that separated North and South. In little more than a year, with the election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency, South Carolina would secede from the Union, followed by six other Southern states. With the firing upon Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor, the nation would be torn apart by civil war. So, too, would be the United States Marine Corps, 20 of whose officers resigned their commissions to take up arms against the government, including fully one-half of all line officers ranked from first lieutenant to major.

Why Marines in the Civil War Were so Under-Prepared

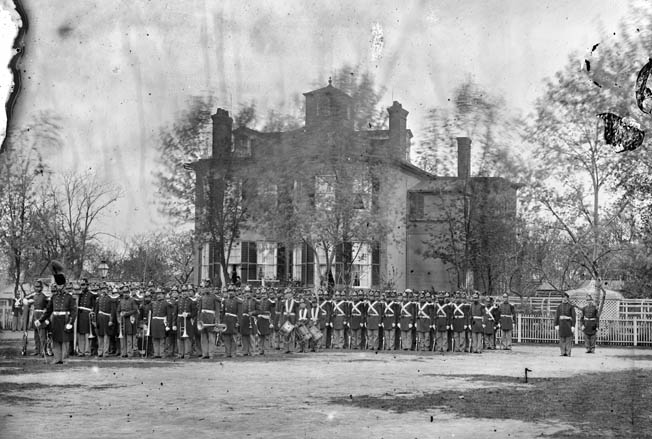

The armed services were ill-prepared for the magnitude of the conflict, and none more so than the Marines in the Civil War. In 1861, the Corps’ total strength numbered just 63 officers and 1,712 enlisted personnel. On July 12, the new secretary of war, Simon Cameron, wrote to request “that the disposable effective Marines now here may be organized into a battalion and held in readiness to march on field service.” In turn, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles ordered Colonel John Harris, commandant of the Marine Corps, “to detach from the Barracks four companies of eighty men each, the whole under command of Major [John G.] Reynolds, with the necessary officers, non-commissioned officers and musicians, for temporary field service under Brig. General [Irvin] McDowell, to whom Major Reynolds will report. General McDowell will furnish the Battalion with camp equipage, provisions, etc.”

The order to march did not sit well with some. Second Lieutenant Robert E. Hitchcock, the post adjutant, wrote to his parents on July 14: “Last night after I passed down the line to receive the reports of the companies, I was met by Capt. [James Hemphill] Jones, who said to me, ‘Mr. Hitchcock, prepare to take the field on Monday morning.’ So tomorrow morning will see me and five other lieutenants with 300 Marines on our way to Fairfax Court House to take part in a bloody battle which is to take place, it is thought, about Wednesday. This is unexpected to us, and the Marines are not fit to go into the field, for every man of them is as raw as you please, not more than a hundred of them have been here over three weeks. We have no camp equipage of any kind, not even tents, and after all this, we are expected to take the brunt of the battle. We shall do as well as we can under the circumstances: just think of it, 300 raw men in the field!”

Reynolds, at least, was well chosen for the task. A Mexican War veteran with 35 years of military service, he knew instinctively what to expect. The same could not be said for the troops under him. Twelve noncommissioned officers commanded the four companies, which included 324 privates. Three musicians and one apprentice music boy were also assigned. Some were enlisted as recently as July 8 and had less than a week’s drill under their belts. The majority of the battalion had enlisted during May and June. Only seven privates had been in the Corps prior to the opening gunfire at Fort Sumter, and only 16 men had seen any active service.

Two Novice Armies at Bull Run

Under Reynolds and his second in command, Major Jacob Zeilin, the 350-man battalion left Washington to participate in the looming battle. As Reynolds’ battalion marched through the nation’s capital, the men were cheered and applauded as the saviors of the Union. After crossing the Long Bridge across the Potomac into Virginia, the battalion swung in behind Captain Charles Griffin’s battery of flying artillery, known as the West Point Battery. There they linked up with the Army of Northeastern Virginia, the largest field army ever gathered in North America. It was led by Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell a staff officer who had never commanded troops in combat.

McDowell’s plan was to move westward in three columns and make a diversionary attack on the Confederate line at Bull Run with two columns, while the third column moved around the Confederates’ right flank to the south, cutting the railroad to Richmond and threatening the rear of the enemy army. He assumed that the Confederates would be forced to abandon Manassas Junction and fall back to the Rappahannock River, the next defensible line in Virginia, which would relieve pressure on the U.S. capital.

Reynolds’ battalion was incorporated into the 16th U.S. Infantry, part of a brigade commanded by Colonel Andrew Porter. “The marines were recruits, but through the constant exertions of their officers had been brought to present a fine military appearance, without being able to render much active service,” wrote Porter. “They were therefore attached to the battery as its permanent support through the day.” In this way, Porter sought to lessen the likelihood that the Marines would see much, if any, fighting that day.

The untried McDowell led his unseasoned Union army across Bull Run against the equally inexperienced Confederate Army of Brig. Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard. His plan depended on speed and surprise—two elements that were sorely missing in his grass-green army. To begin with, the march south took twice as long as expected, owing to a mix-up in the issuing of rations. Columns soon became hopelessly disorganized; several regiments lost their way in the dark.

Reynolds’ Marines found themselves facing an unexpected challenge: the artillery unit to which they had been attached contained six horse-drawn cannons, which raced ahead of the marchers at every opportunity. As Reynolds reported later: “The battery’s accelerated march was such as to keep my command more or less in double-quick time; consequently the men became fatigued or exhausted in strength.” The sweltering July temperatures added to the Marines’ tribulations.

Marines Break in Manassas

Crossing Bull Run at Sudley Ford, Brig. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s Union brigade fell on the Confederate left, held only by Colonel Nathan “Shanks” Evans’ under-strength brigade. Griffin’s battery, followed closely by the Marines, splashed across the creek and opened fire from a range of 1,000 yards. The Confederates found themselves at an initial disadvantage, but the inexperienced Federal troops soon buckled under the intense firing and began to fall back. Porter’s brigade, including Griffin’s battery and the Marines, held firm, but the arrival by train of Confederate reinforcements led by Brig. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston quickly changed the course of the battle. A brigade of Virginians under a recently promoted brigadier general from the Virginia Military Institute, Thomas J. Jackson, rallied at Henry House Hill.

Griffin’s battery and a second Union artillery battery under Captain J.B. Ricketts were ordered to take the hill, supported by other infantry and Reynolds’ Marines. The fighting was intense but indecisive until the chance arrival of an unknown regiment tipped the scales. Griffin wanted to open fire on the dark-clad soldiers, but Major William F. Barry, McDowell’s chief of artillery, ordered him to hold his fire. Barry thought the regiment was Union reinforcements. Instead, it was Colonel Arthur Cumming’s 33rd Virginia, whose members suddenly unleashed a murderous fire on Griffin’s gunners and the supporting Marines. Confederate Brig. Gen. Bernard Bee was so impressed by Jackson and his men that he shouted, “There is Jackson standing like a stone wall. Let us determine to die here, and we will conquer. Rally behind the Virginians!”

The Union troops, including the Marines, broke and fled. Without support, Griffin’s battery was overrun. “That was the last of us,” he reported. “We were all cut down.” Reynolds feverishly attempted to rally the Marines, but another Confederate charge drove them from the hill. In his official report after the battle, Porter commended many soldiers, including “Major Reynolds’ marines, whose zealous efforts were well sustained by his subordinates, two of whom, Brevet Major Zeilin and Lieutenant Hale, were wounded, and one, Lieutenant Hitchcock, lost his life.” In addition to Hitchcock, nine enlisted Marines were killed in action and presumably buried in the mass graves dug by the Confederates near Sudley Church. Sixteen enlisted men were wounded in addition to the officers, and another 20 were taken prisoner. It was, the Marine commandant lamented, “The first instance recorded in its history where any portion of [the Corps’] members turned their backs to the enemy.”

To be fair, there were extenuating circumstances, most particularly the disastrously short amount of time the Marines had had to train before being rushed to the front. Nevertheless, as the least experienced soldiers in McDowell’s woefully inexperienced army, the Marines gave a reasonably good account of themselves under fire, and their 13 percent casualty rate was nearly equal to the Regular Army battalion, the most experienced unit in the Federal army at Bull Run.

Marines at Fort Wagner

Following Bull Run, Congress only slightly enlarged the size of the Marine Corps due to the priority given to the Army and after filling detachments for the ships of the Navy (which had more than doubled in size by 1862), the Marine Corps was only able to field one battalion at any given time. Marines from ships’ detachments as well as ad hoc battalions took part in the landing operations necessary to capture bases for blockade duty. These were mostly successful, but an amphibious landing to seize Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor in September 1863 would be another story.

By the summer of 1863, the Charleston defenses had continued to withstand any Union offensive. Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren replaced Admiral Samuel Du Pont as commander of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron and proposed a joint Navy-Army-Marine assault to seize outlying Morris Island and then move on Fort Sumter itself. He asked Secretary Welles for an extra battalion of Marines to be combined with another battalion assembled from those already serving in the fleet to form an assault regiment. Harris, in turn, put together a motley assemblage of troops—anyone he could grab, including recruiters, transients, and the walking wounded—and placed the now recovered Zeilin in command.

Dahlgren and Army Brig. Gen. Quincy A. Gillmore, agreed to begin the campaign by seizing Fort Wagner on Morris Island. Union gunners made use of a new piece of artillery known as the Requa gun—25 rifle barrels mounted on a field carriage used for rapid firing. On July 10, Gillmore’s soldiers landed safely on the far side of the island, but the subsequent overland attack the next day met with a bloody repulse. One week later, Massachusetts-born Colonel Robert Gould Shaw led a doomed assault on Fort Wagner spearheaded by the African American 54th Massachusetts Infantry. Shaw and 54 of his men were killed, and another 48 were never accounted for. Other Union regiments from Connecticut, New York, and New Hampshire fared no better.

Gillmore called off the all-out attack and ordered his engineers to dig a number of zigzagging approach trenches. While they dug, calcium floodlights, another military novelty, were flashed at the defenders, blinding them enough to prevent accurate return fire. But the ground the Union soldiers were digging through was shallow sand with a muddy base. The trenching efforts also began to uncover the badly decomposed Union dead from the previous assaults on Fort Wagner. Disease and bad water plagued the soldiers as well.

A Disastrous Assault

Dahlgren planned for Zeilin’s Marines to make a landing and support the Army soldiers already on shore, but Zeilin surprisingly objected. He claimed his force was “incompetent to the duty assigned it. Sufficient sacrifice of life has already been made during this war, in unsuccessful storming parties, to make me anxious at least to remove responsibility from myself.” Zeilin also complained that many of his Marines were raw recruits and that it was too hot to train them. “No duty which they could be called upon to perform requires such perfect discipline and drill as landing under fire,” he said. A furious Dahlgren cancelled the Marine landing, recording in his diary: “The Commander of Marines reports against risking his men in attacking [enemy] works. What are Marines for?” Subsequent historians have rebutted Zeilin’s claim that his men were inexperienced, noting that 60 percent of the new Marine battalion and 90 percent of the fleet battalion had at least a year’s experience.

When Zeilin fell ill, Captain Edward M. Reynolds (the son of Lt. Col. George Reynolds of Bull Run fame) took command of the battalion. After the Confederates’ surprise evacuation of Fort Wagner, Dahlgren moved swiftly to attack Fort Sumter, ordering an attack on the fort on the evening of September 8 by 500 Marines and sailors in 25 small boats led by Navy Commander Thomas H. Stevens. Dahlgren learned at the last moment that Gillmore was planning a separate boat attack on the fort that same night. Attempts to coordinate the attacks faltered over the question of whether the Army or the Navy would exercise ultimate command of the assault.

Reconnaissance also failed to reveal the need for ladders to climb the breastworks. The Confederates, who had captured a Union codebook and deciphered Dahlgren’s signals, knew when and where the attack was coming. The surrounding forts and batteries trained their guns on Sumter’s seaward approaches; the Confederate ironclad Chicora waited in the shadows behind the fort. Captain Charles G. McCawley, a future commandant of the Marine Corps, was the senior Marine in the night assault. He decried the lengthy delay before the landing boats were launched, noting that there was “great confusion; the strong tide separated them, and I found it quite impossible to get all my boats together.”

Confederate sentries fired a signal rocket alerting the harbor batteries to open fire. Only 11 of the Marines’ 25 boats managed to land on the rocks beneath the fort; the others were sunk or became lost in the darkness. McCawley’s boat never landed. One Marine officer who did make it ashore, 2nd Lt. Robert L. Meade of Tennessee, recorded in his diary: “My men suffer[ed] from the musketry fire and the bricks, hand grenades, and fireballs thrown from the parapet.”

The assault ground to a halt within 20 minutes. The 105 surviving Marines, unable to reach the parapets or withdraw to sea in their now splintered boats, surrendered. Meade spent the next 13 months in a Columbia, South Carolina, prison camp. Twenty-one enlisted Marines, less fortunate, died in captivity at the notorious Confederate prison at Andersonville, Georgia.

An Attempt to Cut the Confederate Supply Lines

By the fall of 1864, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman and his army of more than 60,000 men had taken Atlanta and headed east across Georgia toward the sea. In a telegram to Army Chief of Staff Henry W. Halleck, Sherman advised: “I would like to have [Maj. Gen. John] Foster break the Charleston-Savannah Railroad about Pocotaligo about the 1st of December.” On November 30, at the Battle of Honey Hill, also known as Boyd’s Neck, Foster failed in his attempt to sever the railroad.

A battalion of 157 Marines, led by 1st Lt. George G. Stoddard, redeployed aboard Navy ships for another attempt to break the railroad. “Soon after dark on the 5th I received orders from the Admiral to form my battalion and proceed on board the Flag Steamer Philadelphia for an expedition up the Tulifinny River,” Stoddard recounted in his official report. “Embarked about midnight under orders to land the next morning, cover the landing of the artillery and advance on the enemy.”

At dawn on December 6, a combined force of Marines, sailors, and soldiers landed on Gregorie Point, South Carolina. “We advanced on the right of the Naval Battery and came under fire about 11 a. m., deployed the whole battalion as skirmishers on the right, and advanced into the woods beyond Tulifinny cross roads driving the enemy before us,” wrote Stoddard. Union troops captured the Gregorie Plantation home, quickly moved toward the Charleston-Savannah Railroad, and surprised the 5th Georgia Infantry, capturing its colors. A corps of 343 Citadel cadets, bivouacking four miles away, heard the fire and marched at a run to Gregorie Point.

In the early morning hours the next day, the cadets and three companies of Georgia infantry mounted a surprise attack on the center of the Union position. Marines were in the center of the Union line, supporting the Army and Navy field artillery batteries. As the cadets slowly inched their way forward, they were met by withering musket fire. Cadet Private Farish C. Furman, a 19-year-old sophomore, later wrote of seeing “a stream of fire shoot out from the bushes in front of me, accompanied by the sharp crack of a rifle. The ball fired at me missed my head by a few inches and buried itself in a tree close by.” The cadets returned fire and mounted a bayonet attack aimed at the Union line, but were quickly forced to retreat.

Union forces prepared to counterattack. As the bluecoats emerged from a swampy, heavily wooded area, they began running across the open field toward the cadets, traversing “a dense swamp, from knee to waist deep.” It was so thick, Stoddard reported, “that you could not see a man three or four paces from you.” The Citadel cadets lifted their rifles and filled the air with Minie bullets. After suffering many casualties, Union troops withdrew to their trenches.

On December 9, Union forces made a final assault against the Confederate defenses. The Marine battalion formed on the far right of a 600–man skirmish line. To the right of the Marine battalion was the Tulifinny River. The cadets were camped directly ahead of the Marine position. Stoddard’s men came within 50 yards of the railroad tracks near the river before the 127th New York Volunteers on their left began to retreat. The Marines on the extreme right continued forward. Stoddard reported: “I found myself unsupported and nearly cut off. I faced my men about, but having no means of telling proper direction, kept too much to the right and struck the Tulifinny River. This turned out to be fortunate, as the enemy pursued our left and through the river, taking several prisoners. We have lost in killed, wounded and missing 23, a list of whom I send herewith. The non-commissioned officers and privates have all behaved in a most gallant manner and I am sure that by their bravery they added to the high reputation the Corps already enjoys.” Despite the failed attack, Stoddard was promoted to captain.

The Battle of Fort Fisher

The Marines suffered another embarrassing failure a few weeks later at the Battle of Fort Fisher. The fort, located at the mouth of the Cape Fear River at Wilmington, North Carolina, safeguarded the Confederacy’s last operational Atlantic port. Shaped like an “L,” the earthen stronghold mounted 39 large-caliber guns augmented by numerous mortars. It was said to be stronger than the celebrated Fort Malakoff at Sebastopol in the Crimea. Walls nine feet high and 25 feet thick waited to repel any invader.

On the morning of December 14, a fleet of 75 Union warships and transports commanded by Admiral David Dixon Porter steamed south from Hampton Roads, Virginia, toward Fort Fisher. Troopships held 6,500 army troops under Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler. Delayed by a storm, the Union armada began bombarding the fort on December 24. A staggering 20,000 shells of all calibers streamed across the water from Porter’s vessels. A landing party of 2,500 soldiers came ashore on Christmas Day but could only reach to within 75 yards of the fort before being driven back. Butler hastily called off the attack. That night, Porter withdrew the fleet out of range of Fort Fisher’s artillery.

On January 6, Porter launched a second invasion. This time the infantry was commanded by Brig. Gen. Alfred Terry; the disgraced Butler had been sacked. A vicious storm off Cape Hatteras again delayed the flotilla, but an 8,000-man landing force went ashore one week later. There followed two more days of intense naval bombardment, while detachments of sailors and Marines gathered for an amphibious assault. Sixteen hundred sailors, armed with cutlasses and revolvers, moved ashore, accompanied by 400 Marines divided into four companies under the command of Captain Lucien L. Dawson. Naval Commander Randolph Breeze led the overall attack.

The assault boats soon ran aground in the rough surf, and the sailors and Marines jumped into the waves with grapeshot and shrapnel whizzing around their heads. A few hundred yards from the fort, the landing party occupied previously dug rifle trenches and waited for the signal to mount a frontal assault. The signal came shortly before 3 pm. The sailors, supported by the Marines, moved out in a single line, heading for a huge hole in the fort’s palisades that the naval bombardment had created. From the start, it was a bloody fiasco, “sheer, murderous madness,” young Navy Lieutenant George Dewey observed from the deck of the steam frigate USS Colorado. Dewey’s own day of glory was coming 34 years later at the Battle of Manila Bay in the Spanish-American War.

The attack was supposed to be simultaneous, but for some reason Terry held back his Army troops on the Confederate left. Instead, for the next six hours, the soldiers, sailors, and Marines fought hand-to-hand with Confederate defenders at Fort Fisher in a badly uncoordinated assault. “I received two or three orders from Captain Breeze to ‘bring up the marines at once; that we would be late,’ so that I had to move off without time to equalize the companies,” reported Dawson. “I took the Marines up and filed across the peninsula in front of the sailors, with skirmishers thrown out.”

When the attackers were driven back, Dawson rallied two companies of Marines to provide cover fire. Several Marines spontaneously joined the Army attack on the main parapet early that evening and helped overrun Fort Fisher. Four hundred of the Confederate defenders were killed or wounded, and more than 2,000 were taken prisoner. Terry’s force lost 900 casualties, and the joint Navy-Marine force lost an additional 200, including 14 Marines killed and another 46 wounded or missing. Six Marines were awarded the Medal of Honor for their actions at Fort Fisher.

Fighting With the Fleet

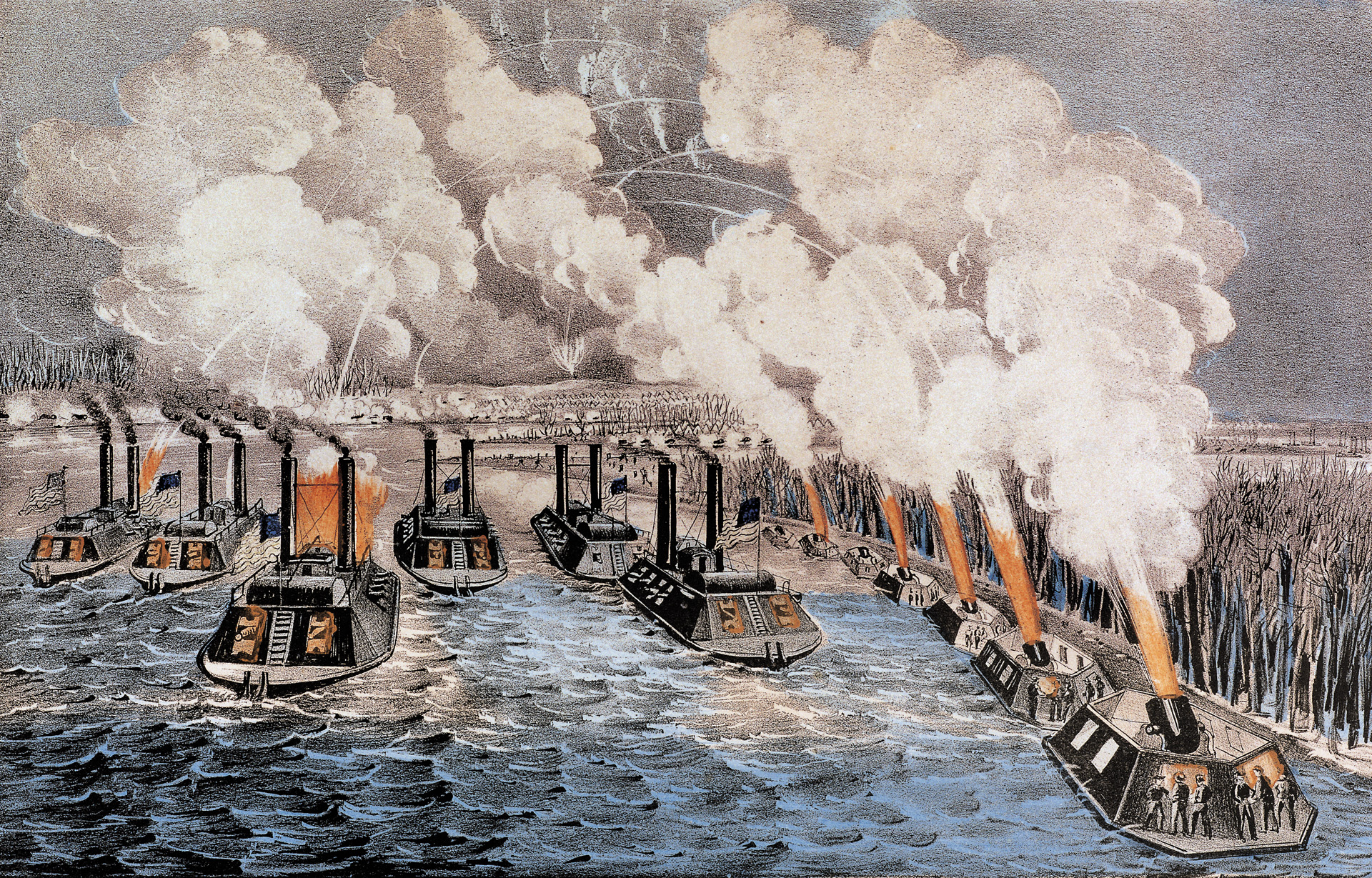

Despite the Marines’ participation in major land battles at First Bull Run, Fort Wagner, Tulifinny Crossroads, and Fort Fisher, the Corps’ main contribution during the Civil War was aboard the ships of the blockading squadrons and inland river flotillas. At the Battle of Mobile Bay in August 1864, quick-firing Marines on Admiral David Farragut’s flagship, the sloop of war USS Hartford, helped beat back an attempt by the Confederate ram Tennessee to sink the vessel. Corporal Miles M. Oviatt, aboard the nearbysloop of war USS Brooklyn, and seven other Marines received the Medal of Honor for their roles in the battle. Oviatt’s citation read: “As enemy fire raked the deck, Corporal Oviatt fought his gun with skill and courage throughout the furious two-hour battle.” Farragut himself said of the Marines, “I have always deemed the Marine guard one of the great essentials of a man-of-war.” And Rear Admiral Samuel Du Pont said even more emphatically, “A ship without Marines is not ship of war at all.”

All in all, the Marines played a comparatively small role in the ultimate Union victory in the Civil War. Their reputation as the nation’s premier amphibious unit would not reach fruition until many years later, in World War II, when the Corps put into effect in the South Pacific the lessons learned the hard way at Fort Fisher: unity of command, parallel planning, rehearsed landings, and close integration of naval gunfire support. Said one company-grade Marine officer who had taken part in the botched attack at Fort Fisher, “The war was our great opportunity, and we owlishly neglected it.” The Marines would not neglect their even greater opportunities at Guadalcanal, Tarawa, Iwo Jima, Okinawa and other Pacific stepping stones eight decades later. In that way, at least, their losses in the Civil War had not been in vain.

For more stories of U.S. Marines in the Civil War, World War II and beyond, subscribe to Military Heritage magazine.

I volunteered as a living historian and as a member of the USMC Historical Company at HFNHP portraying a private of Marines attired in the 1852 fatigue uniform (worn from 1839 to 1859) and am armed with an authentic M1842 Springfield .69 caliber smoothbore musket and 18″ bayonet used by the Corps at the time. I am a native of nearby Charles Town, Jefferson County, WV (where Brown was tried and then executed). I also served our Corps from 1967-1971 with a tour in South Vietnam. Anyone that would like to read the United States Marine Corps – Historical Company’s narrative on this event from the Marine Corps point of view please PM me. Semper Fi!

As a Canadian veteran I am always interested in history of the Marine Corp.

Excellent! My background is a that of a military historian and recently have been doing some genealogical research on my ancestors. One of my Great Great Grandfathers was a prisoner who died at Andersonville in Georgia. On both sides of my Mother’s and Father’s Family we have ancestors who fought on both sides of the war as Confederates and as Union troops. Hence, divided loyalties as is the case with many Families in the Border States. It is only recently that I have discovered we had several distant cousins who served in the Marines during the American Civil War. My service was as a Field Artillery Officer in the United States Army predominantly in Alaska and the West Coast of the United States and the beautifully sunny Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Duty, Honor, Country!