By William E. Welsh

The guide shook uncontrollably when the gray-clad general pointed his pistol at him in the backwoods of central Georgia on the evening of July 21, 1864. Disgusted with mill worker Case Turner’s various explanations and convinced that the guide was deliberately leading them astray, Maj. Gen. William H.T. Walker threatened to shoot him on the spot. A member of Walker’s staff, Major Joseph Cumming, intervened on the guide’s behalf, and Walker reluctantly lowered his pistol. The long, gray column that Turner was leading through the undergrowth on the fringe of Mrs. Terry’s millpond three miles east of Atlanta once again lurched forward in search of the enemy, already in place less than a mile to the north.

Walker’s division, in Lt. Gen. William “Old Reliable” Hardee’s Confederate corps in the Army of Tennessee, had embarked on an exhausting, 12-mile flank march after receiving orders from General John Bell Hood, the new commander of the 60,000-man army. Instructed to launch a sledgehammer attack on the enemy at daybreak, Hardee had fallen nearly six hours behind schedule, at which point Walker pointed his gun at the guide’s head.

“He’ll Hit You Like Hell, Before You Know It”

Walker’s act reflected the combined sense of desperation and frustration facing the Confederate forces in the wake of the Union advance into northern Georgia that spring and summer. When the Federals moved into the Peach State, they were organized into three armies totaling 90,000 men under the command of Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman. His counterpart, General Joseph E. Johnston, had been assigned to lead the Army of Tennessee following the poor performance of General Braxton Bragg at Chattanooga in November 1863, when the Federals broke a two-month-long siege of the town and drove the Confederates across the Tennessee border into Georgia. Sherman was under orders from Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, who had been elevated to general-in-chief of all Federal armies in March 1864, to smash Johnston’s army and press into the enemy interior, wrecking anything—military or civilian—in his path.

By mid-May, Sherman had compelled Johnston to embark on a gradual retreat toward Atlanta. Johnston, a master of the prepared position, delayed Sherman as long as possible, but by the first week of July Sherman’s troops were less than 10 miles from Atlanta. The only thing that stood between them and the key manufacturing center and rail hub was the Chattahoochee River. Confederate President Jefferson Davis implored Johnston to mount a counterattack, but Johnston failed to rise to the occasion. On July 9, he withdrew to the south bank of the Chattahoochee. A week later, Sherman had all his forces across the river. Johnston received a telegram on July 17 from Adjutant General Samuel Cooper informing him that he had been relieved of command and instructing him to turn over the army to Hood.

Upon hearing of Hood’s appointment, Union Maj. Gens. James McPherson and John Schofield, who had graduated with Hood in the class of 1852 at West Point, warned Sherman that the new Confederate commander would strike them hard. “He’ll hit you like hell, before you know it,” Schofield told Sherman. That was precisely what Sherman wanted. He relished the idea of fighting the enemy on open ground rather than continuing to go up against prepared entrenchments.

The Confederate government wanted a fighter at the head of the Army of Tennessee, and that’s exactly what it got. On July 20, Hood attacked Maj. Gen. George Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland as it crossed Peachtree Creek. A three-hour delay in the attack gave Thomas just enough time to entrench and brace for the attack. Hood’s first sortie against Sherman was easily repulsed by the battle-tested Federals.

Federals Take Bald Hill

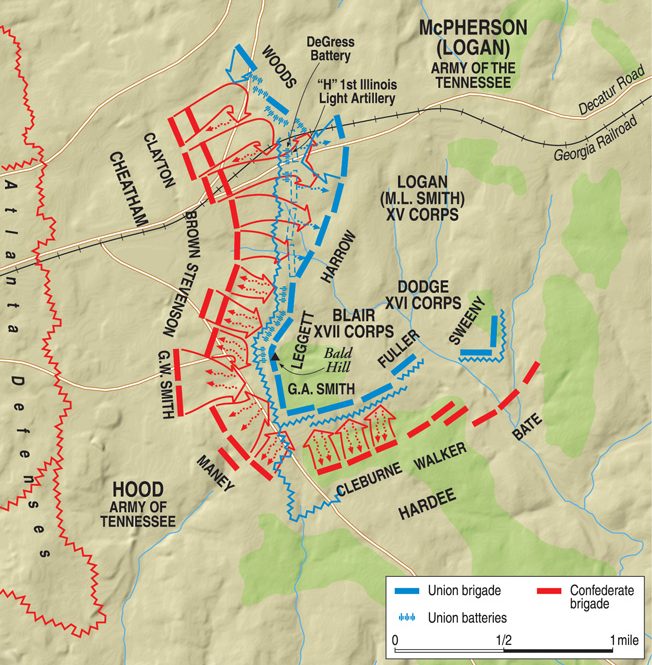

Sherman shifted his focus to the opposite flank. Aware that the majority of Hood’s troops were still in the vicinity of the creek, Sherman ordered McPherson to strike the Confederate right near the Georgia Railroad junction connecting Atlanta to Decatur. McPherson in turn sent Maj. Gen. Francis Blair’s XVII Corps toward the city. Hood anticipated the move and shifted 2,000 cavalrymen under Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler to hold the low ridgeline east of the city until they could be relieved by infantry. The highest point in the ridgeline, at its southern end, was a barren knoll known as Bald Hill. Both sides spotted it and rushed toward it. Wheeler’s troopers were the first to arrive, dismounting to fight on foot against Blair’s troops.

At dusk on July 20, Hood ordered Hardee to send his reserve division, which was led by the hard-fighting, Irish-born Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne, to relieve Wheeler’s troopers. Cleburne deployed his brigades in a line of battle stretching from the Georgia Railroad to Bald Hill. When Wheeler shifted his troops south the following morning, he noticed that Blair’s left flank was in the air, and the cavalry commander sent word to Hood informing him that the Federal position opposite Bald Hill invited a flank attack.

The Federals struck first, attacking Bald Hill at mid-morning on July 21. The soldiers in Brig. Gen. James Smith’s Texas brigade of Cleburne’s division were in the process of entrenching on the knoll when they were overrun by Brig. Gen. Manning Force’s brigade of Blair’s XVII Corps. Smith’s Texans hastily withdrew to a wooded tract west of Bald Hill. Hood drew up plans for Hardee’s corps to make a long night march and come in behind McPherson’s position the following morning. The 12-mile march called for Hardee’s corps to march six miles south to Cobb’s Mill, then turn north to march another six miles to the Widow Parker’s house. From there, the corps was to fan out on an east-to-west axis and roll up Blair’s corps. To fix McPherson’s army in place and prevent him from reinforcing units on the southern part of the battlefield, Hood ordered Maj. Gen. Benjamin Cheatham’s corps to attack east along the Georgia Railroad while the right wing of Hardee’s corps attacked from the rear.

Hood’s plan seemed reasonable enough, but he had overlooked the difficulty that Cleburne would face in withdrawing his men from their position. The fighting between Cleburne’s division and Blair’s men had continued after nightfall. Hardee ordered him to leave his skirmishers behind to mask the withdrawal of the majority of his command.

Preparing For the Assault

Due to the delay in getting the men out of Atlanta, Hardee’s march fell six hours behind schedule. By daybreak his lead column had only reached the halfway point, Cobb’s Mill on the Fayetteville Road. Confederate officers persuaded the mill’s owner and Turner, a mill worker, to help them find the most concealed and quickest route through the forest. After a brief rest, Hardee’s corps continued north toward the Widow Parker’s house. To give the four divisions more room to deploy, the corps split up at a fork in the road near the house. Cleburne turned left onto the Flat Shoals Road, while the divisions of Walker, Brig. Gen. George Maney, and Maj. Gen. William Bate continued to the Widow Parker’s. It was after 11 am before the three divisions finally reached the house. Without pausing to rest, the troops plunged into the woods toward the enemy position.

To reach their point of attack, Bate and Walker had to skirt Terry’s millpond, which had been created by a dam across a portion of Sugar Creek. North of the millpond smaller streams fed into Sugar Creek. Without time to reconnoiter the enemy’s position, Hardee didn’t know exactly where the Federal units were located. As a result, he deployed his troops too soon. Many had to struggle for nearly a mile through the undergrowth to reach their jumping-off positions. “The whole country through which we passed was one vast densely-set thicket—a line of battle could not be seen 50 yards,” wrote one Confederate officer.

The ordeal in the woods was difficult for all the Southern troops, but by noon, Hardee’s four divisions had managed to array themselves to attack. Because of heavy straggling on the night march, only 9,000 of the 14,000 men in Hardee’s corps were present. At noon, Maney’s and Cleburne’s troops emerged from the woods opposite XVII Corps’ unanchored left flank at Bald Hill. However, Walker and Bate were surprised to find a Federal battle line confronting them; they had been led to expect no resistance. The Union troops belonged to Maj. Gen. Grenville Dodge’s XVI Corps, which was en route across the rear of McPherson’s army to a position on Blair’s left flank. Federal scouts had warned Dodge that Confederates were advancing from the south, and he had deployed his men into line in anticipation of an attack. If Hardee had been able to launch his attack 30 minutes earlier, Bate and Walker would have been largely unopposed.

The Confederate Attack Stopped Dead

The four divisions of Hardee’s corps were supposed to attack simultaneously, but the rough terrain disrupted that plan. Bate’s division on Hardee’s extreme right flank attacked first, striking Union Brig. Gen. Elliot Rice’s brigade of Brig. Gen. Thomas Sweeny’s division, which was supported by a battery of six 12-pounders from the 1st Missouri Light Artillery. Because of straggling, Bate had only about 1,200 muskets, one-third of his actual strength, available for the assault. The Union gunners poured a wall of lead into the enemy’s well-dressed ranks. Only one regiment, the 5th Kentucky, managed to cross Sugar Creek and ascend the hill.

The 5th Kentucky squared off against the 2nd Iowa but was unable to push the Hawkeyes back. On the left, a Florida brigade had the unfortunate luck to run into a battery of the 14th Ohio Light Artillery. The battery of 3-inch ordnance guns was ably led by Lieutenant Seth Laird, who directed a steady fire at the Florida troops. Only a handful of Floridians were able to make it to within 50 yards of the battery before being forced back. After 30 minutes of fighting, the Confederates fell back to the protection of the woods.

The extensive forest on the southern end of the battlefield precluded Hardee from putting his own artillery into action. Most of the artillery was at the back of the column, and even when it was brought forward it proved impossible to get the limbered guns through the dense undergrowth. Sweeny’s other brigade, led by Colonel August Mersy, deployed on the right of Rice’s brigade. Next to it was Colonel John Morrill’s brigade. Because of his position between the two Union brigades, Laird was able to turn his guns and shell Walker’s division as well.

From a knoll a half-mile to the rear, McPherson watched the Confederates attack the brigades of Mersy and Morrill. One of Mersy’s regiments, the 66th Illinois, recently had purchased 16-shot Henry repeating rifles, and their steady wall of fire, buttressed by Laird’s canister and shell, drove the Georgians back to the safety of the woods. The feisty Georgians reemerged for a second attack, but again the charge was shattered by superior Union firepower.

Morrill’s right flank was in the air and therefore ripe for attack. Unfortunately for the Confederates, the 64th Illinois on Morrill’s right flank also was armed with Henry repeaters. Brig. Gen. States Rights Gist threw the full weight of his four regiments against two regiments, the 18th Missouri and 64th Illinois, on Morrill’s right flank. The Missourians concealed themselves well behind a fence, and when Gist’s troops came within range the Federals blasted them with three well-aimed volleys, sending them reeling back. Laird’s guns then turned their attention to shelling Gist’s troops. Gist, who was on horseback, miraculously managed to avoid the flying shell fragments, but he was wounded in the hand by a bullet and reluctantly turned over command to Colonel James McCullough of the 16th South Carolina.

When Walker saw Gist retiring from the field, he kicked his gray charger and rode into the thick of the fighting to rally the brigade. “One more charge and the day is won!” he cried. “Follow me!” The Federals saw the Confederate general and began firing in his direction. Walker’s horse was shot from under him. The wiry general stood up and was struck square in the chest by a bullet that pierced his lungs, killing him instantly. With both Gist and Walker out of the action, the attack came to an abrupt end.

“The Enemy’s Line Seemed to Crumble to Earth”

At that point, McPherson and his staff were hastily trying to assemble troops to plug the gap between the two corps. Neither of the two corps already engaged with Hardee had troops to spare, so McPherson sent word to Maj. Gen. John Logan, commanding XV Corps, to send Colonel Hugo Wangelin’s brigade, which was being held in reserve, south to plug the gap. Until the reserves arrived, Brig. Gen. Giles Smith’s division of XVII Corps, deployed on the west side of the gap, dispatched as many troops as it could spare to prevent the enemy from exploiting the half-mile-wide gap.

Cleburne’s hard-fighting division emerged from the woods at 1:15 pm. Cleburne’s right flank was directly opposite the gap in the Federal line. On the left, Brig. Gen. David Govan’s Arkansas brigade emerged to find it was facing a sturdy Federal line manned by the two brigades of Smith’s division. However, the six regiments of James Smith’s Texas brigade were able to crash through the gap in the Federal line and head straight for the rear of Blair’s XVII Corps.

The two regiments on Govan’s left charged the Federal line but encountered abatis that proved impassable. Backed by a section of guns belonging to the 2nd Illinois Light Artillery, Colonel William Hall’s 3rd Brigade shattered the attack by those two unsupported regiments. “The result of our fire was terrible,” wrote one officer in the 16th Iowa Regiment. “The enemy’s line seemed to crumble to earth, for even those not killed or wounded fell to the ground for protection.”

Govan’s other three regiments were able to enter the gap in the Federal lines along with the Texans. This raised the number of regiments in the rear of Blair’s XVII Corps to nine. Something had to be done. Brig. Gen. John Fuller observed the Texans advance unopposed through the gap in the Federal lines and ordered Laird to fire his 3-inch guns, which had a range of slightly over one mile, at the Texans. He also ordered the 64th Illinois to charge into the gap to slow the enemy advance. Only 90 of the 350 men from the 64th Illinois survived the counterattack.

The Death of General McPherson

About 2 pm, McPherson, his orderly, and Colonel Robert Scott, a brigade commander in Blair’s corps who happened to be riding in the same direction as McPherson, were galloping west on a narrow path through the woods when a group of enemy soldiers suddenly blocked their path. A few of the Confederates shouted, “Halt!” McPherson had no intention of being taken prisoner. He gallantly tipped his hat at the enemy soldiers, bent low over his horse, and broke for the rear. A bullet struck him squarely in the back, nicking the strap holding his field binoculars, and traveled through his lungs. The 35-year-old general thudded to the ground with a mortal wound.

A Confederate officer, Captain Frank Beard of the 5th Texas, asked who the officer was. “Sir, it is General McPherson,” Scott said. “You have killed the best man in our army.” Thinking McPherson already dead, Beard took Scott and the orderly prisoner and led them off. McPherson was subsequently found, barely alive, by Private George Reynolds of the 15th Iowa, who was en route to a field hospital. Reynolds comforted McPherson as best he could, but the general died a short time later. Members of McPherson’s staff could not find their commander, and they reported to Sherman that he was missing. Assuming the worst, Sherman sent a message to Logan informing him that he was now in command of the Army of the Tennessee. McPherson’s body was recovered a short time later and taken by ambulance wagon to Sherman’s headquarters at the Howard House. The hard-bitten Sherman, who could oversee the shelling of Southern civilians without blinking an eye, placed a small flag over McPherson’s face and wept like a baby. “The whole of the Confederacy,” Sherman said, “cannot atone for the sacrifice of one such life.”

“We Let Them Have it Right in the Breadbaskets”

Maney’s division, composed entirely of Tennessee troops, swept forward toward Giles Smith’s division of the Federal XVII Corps. Brig. Gen. Otto Strahl’s brigade, on the extreme left, advanced in three lines toward the entrenched position held by Smith’s bluecoats. At that point, nearly two Confederate brigades were in the rear of Smith’s division, which made it difficult for his men to defend their original battle line on the Flat Shoals Road. Colonel Benjamin Potts, commanding the 1st Brigade of Smith’s division, ordered several of his regiments out of their entrenchments so that they were facing south. Strahl tried to outflank Potts’s brigade, but the blistering fire forced the Southerners to retreat. When Strahl was wounded a short time later, his entire brigade broke off their attack.

The assault went better for Colonel Michael Magevney’s brigade, which caught Hall’s 13th Iowa unsupported in the fishhook where Blair’s battle line bent back toward the east. Magevney’s men made the Iowans pay a steep price for not having withdrawn to a safer position. “We mowed them down with an awful havoc,” wrote Captain Alfred Fielder of the 12th Tennessee. To their credit, the Iowans stood their ground despite suffering high casualties, and Magevney, who was unaware that Cleburne’s troops were in the rear of Blair’s XVII Corps, unwisely broke off his attack.

Once Maney’s troops had retreated to the safety of the woods, the momentum shifted to the small number of Confederates who had actually managed to do what Hood originally envisioned in his tactical plan. Nearly two full brigades moved northwest through farm fields and copses toward Bald Hill, where they found their way blocked by Brig. Gen. William Harrow’s 4th Division of Logan’s XV Corps. The first Federals who went into action were those of Colonel Charles Walcutt’s 2nd Brigade, which deployed in a cornfield. Major Thomas Maurice, chief of artillery for XV Corps, rushed three batteries into position to support Harrow’s division. Harrow fed another brigade, commanded by Colonel John Oliver, into action. The well-led Federals charged the Confederates as they attempted to withdraw.

At 2 pm, Brig. Gen. Mark Lowrey’s brigade of Cleburne’s division, which had been at the back of Hardee’s column, arrived on the field with six regiments of fresh troops. Cleburne put the remnants of two other nearby brigades under Lowrey’s command and ordered the one-time Baptist minister to lead an attack against Brig. Gen. Mortimer Leggett’s position on Bald Hill. Seeing the Rebels massing for an attack, Leggett ordered his men to jump over the parapets and seek cover on the far side of their fortifications. The defenders fired repeated volleys into the enemy, but to their consternation several lines of attackers crested the hill.

Leggett’s troops resorted to an assortment of tactics to drive off the Confederates. On the north end of Bald Hill, Force’s men lay prone, and when the Confederates were on top of them they stood up and fired at them at a distance of 10 yards. “We let them have it right in the breadbaskets,” said a Wisconsin soldier. The Alabama and Mississippi soldiers in Lowrey’s brigade took cover in the trenches, which enabled them to reload in a protected position and then fire over the wall at the bluecoats. This enraged the Federals, who resorted to hand-to-hand fighting with clubbed muskets and bayonets to dislodge the tenacious Confederates. By 3 pm, Lowrey’s troops had withdrawn to lick their wounds. Without the support of the two batteries, Leggett’s division would have been overrun.

Cheatham’s Diversionary Attack

Watching from the second floor of a home located—appropriately enough—beside a cemetery, Hood ordered Cheatham to launch a diversionary attack in the hope of preventing the Federals from reinforcing Bald Hill. Cheatham’s corps was the largest in the Army of Tennessee, comprising three divisions totaling 14,000 men. Cheatham prepared to hurl his entire corps at the Federals and punch through their field works.

The Federal XV Corps opposite Cheatham was now led by Smith, who had taken command of the corps when Logan was promoted to army commander after McPherson’s death. Smith’s 2nd Division, in turn, was handed over to Brig. Gen. Joseph Lightburn. North of the railroad, Colonel Wells Jones led six regiments, and south of the railroad Lt. Col. S.R. Mott commanded three regiments. Deployed in support of these troops were Batteries A and H of the 1st Illinois Light Artillery.

Cheatham’s attack got off to a bad start. Maj. Gen. Carter Stevenson ordered his division forward against the Federal lines a half mile south of the railroad in the vicinity of Bald Hill. Although the two federal divisions defending the sector were weary and had no reserves, Stevenson botched the attack by only committing his two front brigades, and his men gave up after a half-hearted effort. The defense of the area just north of Bald Hill was the responsibility of Colonel John Oliver, who had only three regiments available to fight off the assault. “The firing was very heavy along the entire line,” wrote Major William Brown of the 70th Ohio.

The next division of Cheatham’s corps to advance belonged to Brig. Gen. John Brown, who threw all four of his brigades into the fight against Lightburn’s division. A major Federal strongpoint was the Troup Hurt House, one-eighth of a mile north of the railroad, where four 20-pounder Parrott guns were situated. Two other cannon had been placed between the house and the railroad. Beyond Jones’s right flank was a large patch of marsh that formed a no-man’s land and prevented Cheatham from flanking his opponent’s position by sweeping around from the north.

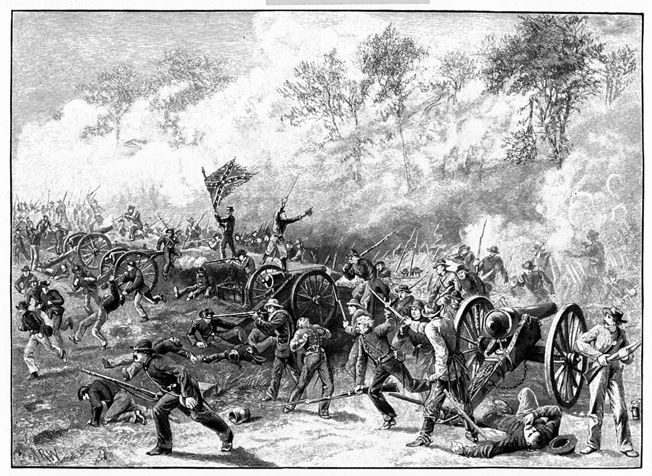

Captain Francis DeGress ordered the crews of the four 20-pounders to begin firing on the Rebels once the Federal skirmishers had pulled back. The shell and canister from the powerful guns ripped great holes in the lines of Brig. Gen. Arthur Manigault’s brigade as it steered toward Jones’s ranks. The battery’s fire so unnerved the Southerners that they broke ranks and fled for the rear. “Things looked ugly,” Manigault wrote of the initial repulse. On Manigault’s right, Colonel Samuel Benton’s Mississippi brigade was stopped cold in its tracks 50 yards from the Federal works by the fire. Benton himself was struck fatally by shrapnel in the chest. Initially, at least, Lightburn’s men had successfully parried the thrust of a corps-sized attack.

Hard on the heels of Manigault’s brigade was Colonel Jacob Sharp’s Mississippi brigade of Brown’s division. “The men saw them, and gathered confidence,” Manigault wrote of his command. Together the two brigades had enough weight to overwhelm the Federals north of the railroad despite their strong artillery support. The first Confederate regiment to fight its way through the Federal works, about 4 pm, was the 10th South Carolina, led by Colonel James Pressley. The South Carolinians streamed through a breach on the south side of the Troup Hurt House, captured a section of Battery H, then charged around to the other side to seize control of the rest of the guns that had caused them so much misery. In a matter of minutes other Confederate regiments began wreaking havoc behind enemy lines north and south of the railroad.

Outnumbered five to one, there was no way Lightburn could rally his men at that location. Seeing Lightburn’s division crumble to his north, Colonel John Coltart, commanding another brigade in Brown’s division, ordered his men forward north of Bald Hill. To defend against Coltart, Colonel Reuben Williams had only 600 men in two regiments to hold off the determined Rebel attack. Twice the Union troops beat back Coltart’s men with well-timed volleys, but several hundred more Confederates appeared on his right flank and delivered a blistering enfilade fire that ripped into the backs of his men. Williams had no other recourse than to order his men to fall back. By 4:15, Cheatham’s corps had wrested control of nearly a mile of field works, an achievement that Hardee had not come close to matching.

Hood’s Missed Opportunity

Lightburn established a new line half a mile east in shallow trenches the Federals had occupied two days earlier. On his left flank, two brigades of Harrow’s division did the same, while Walcutt’s brigade remained in position to protect the right flank of the beleaguered Federals atop Bald Hill. Several thousand Confederates belonging to Brown’s division were in possession of the Federal works and the ground immediately east, but they were milling around, rounding up prisoners, and had become hopelessly intermingled. If Cheatham was going to press his advantage, Brown’s division would have to be reorganized. Several hours of daylight still remained, and the Confederates were on the verge of victory if they could just sustain their momentum.

Hood seemed to have no real sense of what Cheatham had achieved. If he had, he might have ordered newly minted Lt. Gen. Alexander Stewart’s uncommitted corps to march to Cheatham’s assistance. Stewart was an hour away to the northeast, and even the arrival of one of his divisions might have been enough to break the back of Logan’s already exhausted army. The order was never given. “For reasons unknown to me, the battle did not become general,” wrote Stewart.

Another short lull fell over the battlefield while Logan and his generals set about organizing a counterattack to regain the ground given up to Cheatham. Logan also ordered Dodge to send a brigade to assist the Federal right flank. For that task, Dodge selected Mersy’s brigade. Altogether, the Federal right flank received 2,000 additional muskets. Logan also ordered Brig. Gen. Charles Woods, who was positioned on the extreme Federal right beyond the marsh north of the Troup Hurt House, to attack the Confederate left flank. The coup de grace was to be delivered by several batteries of Schofield’s Army of the Ohio near Sherman’s headquarters that began shelling the Confederate left.

Hand-to-hand fighting occurred in many places between the two lines of trenches. About 3,000 Rebels attempted to advance but made no progress. The Federal artillery not only broke up Brown’s efforts to press his advantage against the Federal XV Corps, but also prevented enemy reinforcements in the woods to the west from joining the attack. “Their shells tore through our lines or exploded in the faces of the men with unerring regularity,” wrote Manigault.

Cheatham Withdraws

The soldiers of Manigault’s brigade on the Confederate left were exhausted after protracted fighting, and they found themselves shortly after 4:30 pm under heavy artillery fire and assailed on both flank and front. Mersy’s men charged along the axis of the Georgia Railroad, giving a blood-curdling scream designed to rattle the enemy. About the same time, Harrow’s division began its counterattack against Coltart’s troops just north of Bald Hill. They easily drove the Alabamans back and recovered the field works they had abandoned earlier. The withdrawal of Manigault’s and Coltart’s brigades left Sharp’s Mississippi brigade alone in the center, exposed to enfilading fire.

Brown, who was at the front witnessing the retreat, was furious. He ordered Sharp’s brigade to counterattack Lightburn’s brigade, which by then had joined the fighting. “We charged with an awful yell,” said a lieutenant with the 41st Mississippi. The counterattack was enough to stall the Union forces momentarily, but the momentum was clearly with them. They drove Sharp’s brigade back on Clayton’s division, which was attempting to advance on the Decatur Road. Sensing that XV Corps might be able to recover all of the ground lost to the enemy, Logan spurred his horse and charged west along the Decatur Road behind his advancing troops, rallying them “with fire in his eyes,” in the words of one Ohio private. Logan ordered his subordinates to press the attack at all costs.

Mersy’s horse had been shot from under him during the advance, and he had been injured when the horse fell on him. As he was assisted to the rear, Mersy turned over command of his brigade to Colonel Robert Adams of the 81st Ohio. Adams’s regiment recovered the captured guns, which the Confederates had neglected to haul away. Since he had only partially disabled the guns, DeGress was able to put them back into action immediately with the assistance of some nimble infantry who knew how to load and fire them.

After 30 minutes of hard fighting, the earthworks above and below the Georgia Railroad once again belonged to the Federal XV Corps. Cheatham gave a general order for his men to withdraw, and the officers of the units in the corps reluctantly carried out the order. Their feelings were summed up in the words of a member of the 10th South Carolina. “We [had] built these breastworks, given them up to the enemy, re-taken them at a very heavy sacrifice, and now we had to give them up again.” By late afternoon, Blair had formed a new line a quarter of a mile behind his original line.

The defense of Bald Hill was in the hands of Colonel George Bryant, who had taken command of Force’s 1st Brigade of Leggett’s division when Force was wounded in the face in earlier fighting. Bryant’s men had not been idle during Cheatham’s diversionary attack. Anticipating yet another savage assault on their position before the end of the day, they had feverishly worked to strengthen the earthworks atop Bald Hill. By 5 pm, they had constructed a three-sided, makeshift fort with eight-foot walls. Supporting Bald Hill and the troops southeast of it were the Black Horse Battery and Battery D, 1st Illinois Light Artillery.

Clerburne’s Stragglers Assault Bald Hill

In light of the failure of Hardee’s flank attack to achieve its ultimate objective, it was fortuitous that severe straggling occurred during the night march. By late afternoon, a large number of men who had not yet entered the battle had arrived in the woods south of the Federal lines. Cleburne, who never seemed to give up, rounded up as many fresh troops as he could from his division and sent members of his staff to ask for fresh troops from the other three divisions of Hardee’s corps for a grand assault on Bald Hill.

Cleburne received permission from Maney to commit Colonel Francis Walker’s Tennessee brigade, which until then had not participated in the action. By 6 pm, Cleburne had assembled 3,500 soldiers for the initial assault; another 2,000 were waiting in the woods behind them to lend support if necessary. The first troops to attack Bald Hill in the grand assault were 900 Arkansans from Govan’s brigade, who charged across the open ground toward Hall’s brigade. They managed to capture an outlying earthwork but did not have enough momentum to crack the main line of Federal trenches southeast of the hill.

Bryant’s brigade atop Bald Hill had to hold the knoll against Confederate brigades attacking simultaneously from two directions. Cleburne had planned a classic double convergence to envelop and annihilate the Federal position. Walker’s brigade advanced from the southwest toward the hill while Lt. Col. Morgan Rawls led Mercer’s brigade in a charge from the southeast. Leggett had ordered Bryant to place three regiments on the southern slope of the hill outside the fort to prevent the enemy from sneaking up on it by taking advantage of its blind spots. Walker’s Tennesseans were pummeled by the Black Horse Battery on Bryant’s right flank, which fired double canister into their tightly packed ranks.

The Tennesseans turned to take cover in the woods, but Cleburne rallied the men and sent them back into the teeth of Federal fire from Bald Hill. The carnage was terrible, with canister fire opening huge gaps in the Southern ranks. “As I looked down the line, I could see men dropping by the scores,” wrote a 9th Tennessee soldier. Meanwhile, Rawls’s Georgians had captured an outlying earthwork on the southeast side of Bald Hill, but then Rawls seemed to lose his nerve. Rather than pressing his attack, he left his troops in an exposed position on open ground where they began dropping from repeated volleys of enemy rifle fire. Rawls himself was wounded and turned over command to a subordinate officer.

The second charge of Walker’s men achieved better results. Once again they raced across the open fields with Walker on foot leading them. “They were dropping here and there,” wrote an Ohioan who participated in the hill’s defense. “But they came on like cattle facing a storm, and in a few minutes they were masters of the situation outside.” Walker had placed his hat atop his sword so his men knew that he was among them, which unfortunately made him a rich target for enemy sharpshooters. He was struck in the upper body by a bullet and died on the blood-drenched slopes of Bald Hill.

Battle smoke clung to the hill, and desperate brawls broke out when the Tennesseans crashed into the defenders on the upper slopes. When the Confederates were within 20 feet of the fort, flag bearers jammed their standards into the ground as rally points from which the Tennesseans could assail the fort. On the south slope of the hill, the men of the 27th Tennessee, who hailed from the western portion of the state, captured the flag of the 30th Illinois of Bryant’s brigade.

Soldiers from two brigades, the 11th Iowa and 20th Ohio, of Giles Smith’s and Leggett’s divisions, were packed tightly inside the fort. The best shots from each regiment used slits or cracks in the walls or stood atop the tall palisades and fired at Confederates brave enough to try to assault the fort. Those Southerners who tried to force their way inside the fort through one of its several entrances were shot in the face or stomach and fell back screaming and clutching their wounds.

The Bloodiest Day of the Atlanta Campaign

Shortly before 8 pm, the Confederates broke off the attack. Even though Cleburne had fed the available reinforcements into the battle by that time, they did little to improve the situation. Most of the Confederates who had fought so valiantly retreated to the woods, but a significant number chose to stay close to the fort. They found cover behind a three-foot embankment that stretched about 70 yards opposite the fort and maintained a steady fire against it throughout the night. Union sharpshooters and artillery blasted back at them.

Sherman wired Washington that the fighting had been severe and that McPherson had been killed while on reconnaissance. Likewise, Hood informed Richmond of the death of Walker and noted that his men had fought gallantly. He omitted from his report the fact that both Cheatham and Hardee had been repulsed. The combined casualties for the fighting on July 22 numbered some 10,000 men, making it the bloodiest single day of the Atlanta campaign.

Great article loved the details

Joe Wheeler served as a general in the Confederate Army, then during the Spanish-American war served as a general in the US Army.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Wheeler