By Michael D. Hull

Wing Commander Guy P. Gibson of Royal Air Force Bomber Command was handed the most challenging assignment of his six-year career in the spring of 1943.

After winning the Distinguished Service Order with bar and the Distinguished Flying Cross by the age of 24, the chunky, modest son of an Indian Forest Service official took command of a unit newly formed for “special duties,” No. 617 Squadron. It was destined to gain a unique niche in the history of military aviation.

At the sprawling Scampton Airfield near the city of Lincoln in northeastern England that spring, Gibson oversaw the intense preparation of 700 handpicked pilots, bombardiers, navigators, and gunners for a daring and unprecedented operation—a low-level precision raid by four-engine Avro Lancaster heavy bombers. It was code named Operation Chastise.

Gibson, characterized as an officer who “exerted his authority without apparent effort,“ told the crews, “You’re here to do a special job, you’re here as a crack squadron, you’re here to carry out a raid on Germany, which, I am told, will have startling results. Some say it may even cut short the duration of the war…. All I can tell you is that you will have to practice low flying all day and night until you know how to do it with your eyes shut.”

The targets, kept secret during the squadron’s training, were the Mohne, Eder, and Sorpe dams in Germany’s Ruhr Valley. Since before the start of World War II, Air Ministry planners believed that the destruction of the dams, which stored water vital for production, would cripple Nazi Germany’s economy. The untried weapons chosen for the operation were spherical, five-foot-long bombs (actually mines) that contained five tons of Torpex high explosive.

Developed by Dr. Barnes N. Wallis, an engineering genius who had invented the geodetic aircraft design, the bombs were to be dropped from a height of only 60 feet, skip across the surface of the water, roll down the faces of the dams, and explode underwater. Widespread flooding and damage would result.

After several failures, the “bouncing bomb” had been successfully tested off the southern coast of England. The weapon was so cumbersome that the Lancaster had to be modified to hold it, protruding below the bomb bay. Dual spotlights were also fitted to No. 617 Squadron’s bombers. The big, robust Lancaster was the only aircraft suited for the unique operation.

“The Most Precise Bombing Attack Ever Delivered”

All was made ready for the mission by Sunday, May 16, 1943, and the weather was excellent. That night, 18 Lancasters took off from Scampton, formed up, and thundered at low level across the North Sea and the Dutch coast. Two planes were shot down by German antiaircraft fire, and two had to return to base, one with flak damage and the other after hitting the sea. Another bomber went down when its pilot was blinded by searchlights.

The remaining Lancasters flew on in moonlight through increasing enemy flak and small-arms fire to the Ruhr dams. Gibson dropped the first bomb on the Mohne dam and scored a direct hit. The second plane was hit by flak and crashed, but the third and fourth made successful runs. The dam still held. But the fifth bomber’s run did the trick.

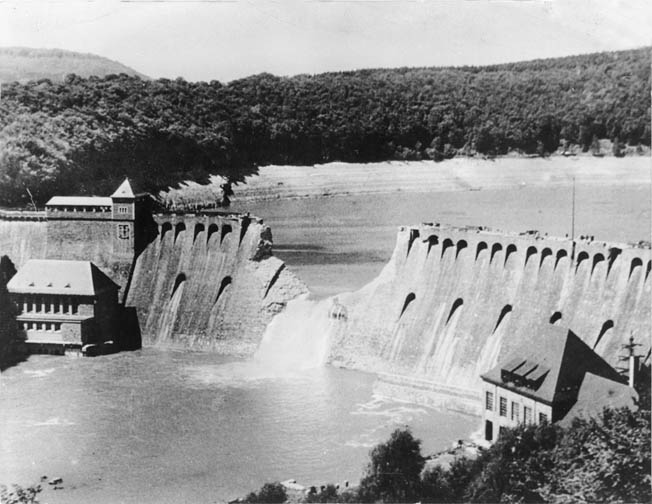

As the Lancasters climbed away, Gibson reported, the top of the dam simply “rolled over and the water, looking like stirred porridge in the moonlight,” cascaded into the valley below.

The Eder dam was well hidden in a valley and difficult to approach. One of the Lancasters dropped its bomb too late, which exploded on the parapet and took the plane with it. After several abortive runs, two more bombers laid their ordnance accurately and breached the dam with spectacular results. The squadron’s remaining bomb damaged the Sorpe dam but failed to cause a breach.

Eight bombers were lost in the operation, and 54 crewmen lost their lives. The cost was high, but the raid gave a major boost to Allied morale. Gibson was awarded the Victoria Cross, Britain’s highest medal for valor, and 33 other members of the squadron were also decorated.

The devastation and widespread flooding inflicted by the raid killed 1,300 civilians, left thousands homeless, damaged 50 bridges, and briefly halted production in the Ruhr. But, because only two of the dams had been breached, the impact was less severe than planned. The dams were repaired by October 1943.

The operation, nevertheless, was remembered as the most celebrated Allied bomber mission of the war. The official Bomber Command history called it “the most precise bombing attack ever delivered and a feat of arms which has never been excelled.”

Developing the “Lanc” Heavy Bomber

The Avro Lancaster was a remarkable plane. From 1942 onward it was the primary British bomber in the Allied aerial offensive against Germany. Sturdy, versatile, and ideally suited for mass production, it had the RAF’s lowest heavy bomber loss rate and was used extensively in high- and low-level day and night raids. Its payload exceeded that of the U.S. Army Air Forces’ Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress and Consolidated B-24 Liberator, and it could carry the heaviest bombs, from 4,000-pounders up to the 12,000-ton “Tallboy” and the 22,000-ton “Grand Slam.”

Many experts termed the “Lanc” the most effective bomber of the war. Aviation historian Owen Thetford called it “perhaps the most famous and certainly the most successful heavy bomber used by the Royal Air Force in the Second World War.” Historian William Green said that a great plane must have “a touch of genius which transcends the good” and “the luck to be in the right place at the right time.” He added, “It must have above-average flying qualities: reliability, ruggedness, fighting ability, and skilled crews. All these things the Lancaster had in good measure.”

Yet the bomber was conceived almost by accident, developed as a result of the failure of its predecessor, the twin-engine Avro Manchester. The Lancaster story began in 1936, when the standard RAF night bomber was the ungainly, soon obsolete Handley Page Heyford, a twin-engine biplane, and when Bomber Command possessed only one squadron of Hendon monoplane bombers. The Air Ministry drew up specifications for a twin-engine heavy bomber that September, and Sir Edwin A.V. Roe, an aircraft design pioneer, proposed a design that was powered by two “new and unorthodox” Vulture liquid-cooled engines.

Named the Manchester, it made its maiden flight from Manchester Ringway Airfield in July 1939, became operational in November 1940, and first saw action on February 24-25, 1941, when it flew a night raid against the French port of Brest. Replacing the twin-engine Handley Page Hampden, the Manchester carried a heavy payload, mounted eight machine guns, and had a maximum range of 1,630 miles, yet it was “one of the RAF’s great disappointments,” said Thetford. Its engine proved unreliable, and it racked up the highest loss rate of all RAF bombers in the war, so it was removed from combat service in June 1942.

But Roe’s design team, headed by brilliant Roy Chadwick, still believed that, with improvements, the Manchester could become an effective bomber. So, four 1,460-horsepower Rolls-Royce Merlin engines were installed on the basic airframe, and the Lancaster was born. Piloted by Captain H.A. “Sam” Brown, the prototype made its maiden flight on January 9, 1941, from Woodford, Northamptonshire. It tested successfully, assembly line work was started immediately, and the first production bomber flew on October 31, 1941. Wing Commander Roderick Learoyd’s No. 44 (Rhodesia) Squadron at Waddington, Lincolnshire, received a welcome Christmas present that December 24 when three of the first operational Lancasters arrived to replace its obsolete Hampdens.

The massive, mid-wing Lancaster had a twin tail and four characteristic power turrets (nose, tail, dorsal, and ventral), all mounting twin .303-caliber machine guns except the tail position, which had four .303s. The ventral turret was soon removed. A spacious bomb bay enabled the plane to accommodate a minimum 14,000-ton payload, outperforming such other Bomber Command “heavies” as the Short Stirling and the workhorse Handley Page Halifax.

Manned by a crew of seven, the Lancaster was comparatively easy to fly, maintain, and repair. It had a maximum speed of 287 miles an hour, a range of 1,660 miles, and a ceiling of 24,500 feet. Most of the aircraft were fitted with an H2S radar “can,” protruding beneath the after fuselage. A few mounted .50-caliber machine guns, some had bulged bay doors in order to carry the Tallboy and Grand Slam bombs, and others were powered by Packard-built Merlin or Bristol Hercules radial engines.

Unlike most combat planes built in large numbers, the Lancaster was little changed during the war. Major design modifications proved unnecessary. A total of 7,377 of the bombers were eventually produced, including 430 built in Canada. The Lancaster became the dominant aircraft of RAF Bomber Command and the mainstay of its regular night raids over Nazi-occupied Europe and Germany. By January 1942, there were 256 Lancasters out of 882 heavies in Bomber Command, and a year later there were 652 Lancasters out of 1,093 bombers. The “Lanc” was loved by its crews.

First Air Raid by Lancasters

The first Lancaster operation carried out was on March 3, 1942, when four bombers of No. 44 Squadron laid mines in Heligoland Bight, off northwestern Germany. They took off from Waddington at 6:15 pm and returned safely five hours later. Seven days later, on the 10th, Lancasters made their first night raid. Two from No. 44 Squadron joined a 126-strong bomber force in a mission to the Krupp munitions center in Essen. Each of the Lancasters carried 5,000 pounds of incendiaries.

That month, 54 planes were delivered to the first three Lancaster squadrons. More rolled off the assembly lines, and further bombardment groups were formed, beginning a grueling three-year series of raids to the heart of the Third Reich as the spearhead of Bomber Command. The RAF’s night raids were complemented increasingly by the daylight missions of U.S. Eighth Air Force B-17 and B-24 bomber groups, and Germany was being bombed around the clock. Although the British had abandoned daytime sorties as being too costly,

Two months later, Lancasters made headlines taking part in one of the most famous air operations of the war, the first of Air Marshal Harris’s 1,000-bomber raids.

Almost 900 bombers, including 73 Lancasters, reached Cologne on the night of May 30-31, 1942, and dropped 1,500 tons of bombs, two thirds of them incendiaries. Six hundred acres of the historic Rhine city were burned and leveled, and a month’s worth of production destroyed. The raid was a victory for the RAF, but it was also a showpiece that could not be easily replicated. Nevertheless, the mission dramatically exhibited the power and potential of Bomber Command, lifted British morale, encouraged the hard-pressed Russians, and impressed the Americans.

Through the summer and autumn of 1942, Lancasters were increasingly deployed in Bomber Command operations, with occasional detachments for coastal patrol and antishipping duties. On July 17, a Lancaster from No. 61 Squadron sank a U-boat. Besides minelaying sorties and attacks on Hamburg, Stuttgart, Mannheim, Duisburg, and Munich in the latter months of the year, the RAF heavies headed for targets in Italy, focusing on Turin, Milan, and Genoa.

The year 1943 began with a number of smaller raids, but on the night of January 16-17, Bomber Command visited Berlin for the first time in more than a year with 190 Lancasters and 11 Halifaxes. Only one Lancaster of No. 61 Squadron was lost. The raid was repeated the following night, however, with 170 Lancasters and 17 Halifaxes, and 22 bombers failed to return.

The bombers were given a higher level of accuracy, meanwhile, through such extensive scientific developments as the “Gee” radio-beam navigation system, the “Oboe” blind-bombing device, ground-scanning radar, and “Window,” strips of aluminum foil dropped in quantity to cause confusion on enemy radar sets. A major boon to Bomber Command operations was the Pathfinder Force, set up in August 1942 and headed by forceful Group Captain Donald Bennett.

Punishing Raids and the Bombing of Berlin

Through the late summer and closing months of 1943, meanwhile, Bomber Command launched a series of punishing raids on enemy targets. On the night of August 17-18, the missile production site at Peenemunde on the Baltic coast was hit by 595 bombers, including 324 Lancasters, causing the Germans’ V-2 rocket program to be put back at least three months. Dusseldorf, Cologne, Mannheim, and other cities were hammered again, and the German capital came in for special punishment at the end of the year.

A campaign known as the Battle of Berlin opened on the night of November 18-19, 1943, when an all-Lancaster force of 440 planes, supplemented by four Mosquitoes, attacked the city. British losses soon mounted. Cloud cover grounded enemy fighters, but intense flak downed nine Lancasters. A simultaneous raid on Mannheim by Halifaxes, Stirlings, and 24 Lancasters resulted in the loss of 23 bombers, including two Lancasters. Another 28 of the Avro bombers went down during a mission on November 26-27, and 14 more crashed in England because of bad weather.

A Berlin mission on December 16-17 was even more costly. Twenty-five Lancasters were lost during the attack, and 29 were destroyed on return to their bases. From November 18, 1943, to March 31, 1944, Berlin was assaulted 16 times by Bomber Command. Lancasters flew a total of 156,308 sorties during the war, dropping 608,612 tons of high-explosive bombs and 51,513,106 incendiaries. Aircraft losses in operational and training crashes totaled 3,349.

Operation Thunderclap: The Firebombing of Dresden

The Lancaster squadrons were kept busy before and after the Allied armies landed in Normandy on June 6, 1944. They attacked enemy coastal batteries and other key targets behind the beaches, demolished a key railway tunnel at Saumur, extensively damaged U-boat and E-boat pens and river bridges in Le Havre, raided V-1 rocket launching sites, and bombed the German port of Stettin, causing heavy damage and sinking five ships. By August 1944, the RAF’s Lancaster force was at peak strength with 42 operational squadrons, including four Canadian, two Australian, and one Polish.

As the Allied armies hammered their way toward the River Rhine frontier in the early months of 1945, the Lancaster force’s 56 squadrons flew both day and night raids in and outside Germany. Rail lines, tunnels, and viaducts received special attention with the Bielefeld viaduct demolished on March 14 in the first operational use of the 22,000-pound Grand Slam bomb. The Lancasters also blasted coastal batteries in the Frisian Islands.

On the night of February 13-14, less than three months before the German surrender, Lancasters played a leading role in Operation Thunderclap, one of the most successful and controversial combat missions of the war. Led by nine Mosquito pathfinders and flying in two waves, 796 bombers unloaded 2,700 tons of high-explosive and incendiary bombs on Dresden, the medieval capital of Saxony and an important manufacturing center and communications hub. Fanned by strong winds, a firestorm devastated large areas of the city before 300 U.S. Eighth Air Force B-17s arrived to disrupt recovery efforts on February 14-15 and March 2. The total death toll was estimated at between 30,000 and 60,000.

Ration Runs and Operation Exodus

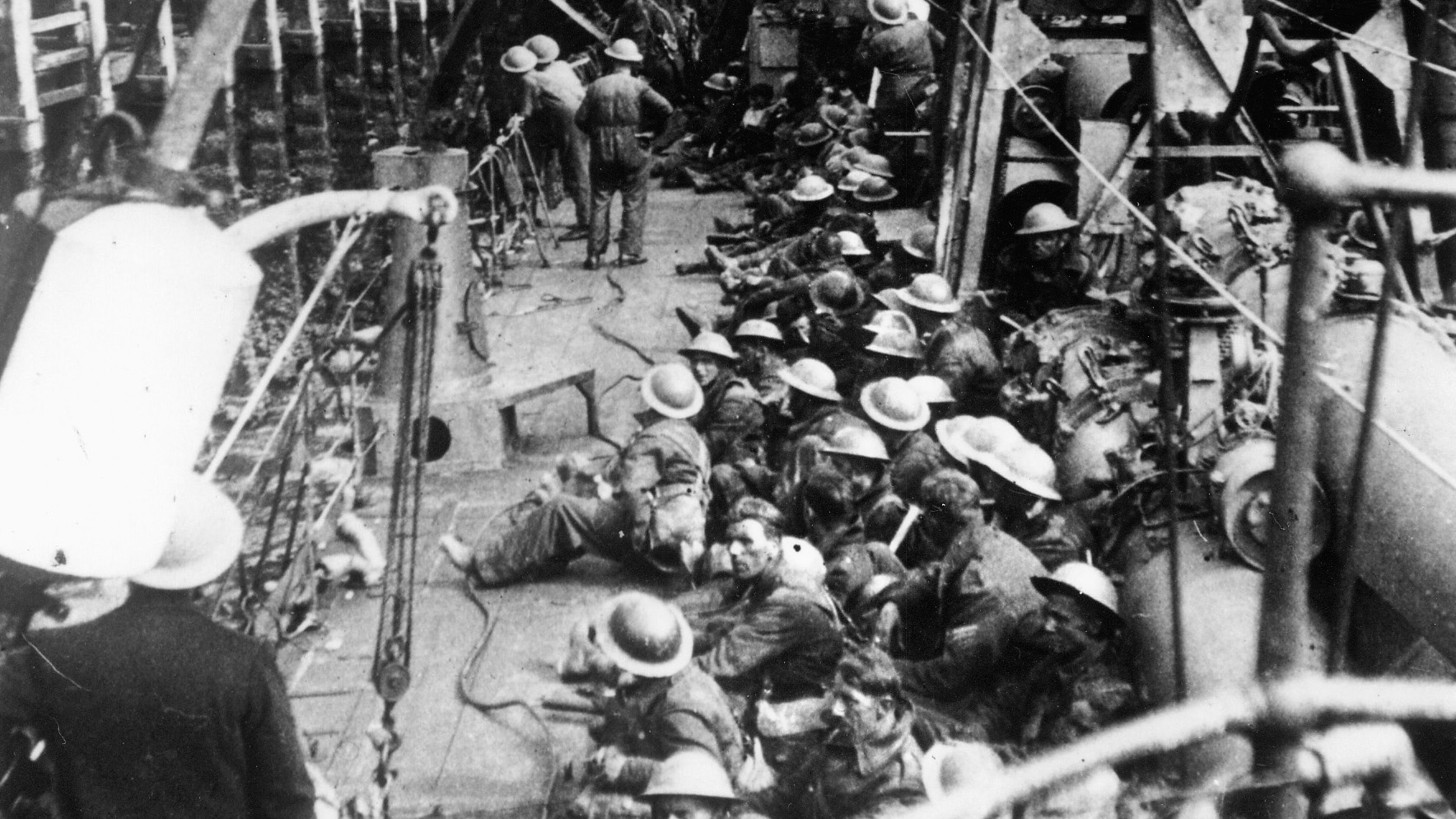

In the final weeks before the German surrender was signed on May 7, 1945, the versatile Lancasters embarked on missions of a different kind, laden with food instead of bombs. During Operation Manna in April-May, bombers from Nos. 1, 3, and 8 Groups flew 2,835 sorties to drop 6,684 tons of rations to the starving people of western Holland. Large areas were still under German control, but the local Wehrmacht commander agreed to a truce and no action was taken against the British planes. The Americans joined the operation, with 400 B-17 runs dropping 800 tons of food in the first three days of May. Lancasters later took part in another humanitarian effort, Operation Exodus, during which Nos. 1, 5, 6, and 8 Groups flew home 74,178 British prisoners of war.

After the war, Lancasters succeeded B-24 Liberators in reconnaissance duties for RAF Coastal Command. Built by Armstrong Whitworth, the last Lancaster was delivered to the RAF in February 1946. Lancasters served in the RAF until December 1953 and were officially withdrawn in a ceremony at St. Mawgan, Cornwall, on October 15, 1956.

The bombers continued to serve in Canada and Argentina, and with the French Navy and the Egyptian, Swedish, and Soviet Air Forces. The Lancaster’s proud heritage is kept alive at annual air shows by the meticulously preserved City of Lincoln, showpiece of the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight.

Very good article…but Lancasters used in line Merlin Engines

Cheers

Son of WW2 fighter pilot

they did experiment with the Hercules radials but they didn’t go into production. Merlins were in very high demand across many different airframe types and were frequently in short supply.

Excellent review of the Lancaster, but the bomb payload quoted of 12,000 tons for the “Tallboy” and 22,000 tons for “Grand Slam” are very ambitious!! The word “tons” needs to be replaced by “pounds”………

The Lancaster was considered by the Americans to drop the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki because it was the only bomber capable of carrying the weight, while the B-29 Superfortresses were having technical problems that were finally ironed out in time.