By Glenn Barnett

By the mid-1930s many people in Australia were concerned that if war came to Europe that Great Britain would not be able to come to their defense against a growing and aggressive Japanese Empire.

In 1936, with the encouragement of the Australian government, several private manufacturing companies combined to form the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation (CAC) to begin work on the first Australian-built warplanes. By 1937 a factory for this purpose was completed at Fishermens Bend in Port Melbourne.

In the meantime, Australian delegations had been sent to Great Britain, other European countries, and the United States to evaluate aircraft designs suitable for Australian needs and that Australian companies would be able to produce. The world-class Supermarine Spitfire and Hawker Hurricane fighters were beyond the abilities of Australian firms at that time. The design chosen was the North American Aircraft (NAA) NA-16 model (sometimes called the NA-33), a purpose-built trainer with inline seating for pilot and instructor. It was cheap and relatively easy to produce. In the United States this design would evolve into the popular T-6 Texan trainer. It was exported as the Harvard.

The Australian decision caused some grumbling in Great Britain because it was expected that a British aircraft would be selected. The British even asked the Australians to reconsider their decision, but to no avail. Australian Minister for Defense Archdale Parkhill justified choosing the NA-16 “on the grounds of urgency and the lack of a suitable British design.” It should be noted that Australia was not totally against British designs. During the war they would also build under license the British Bristol Beaufort and later the de Havilland Mosquito.

Building a War-Fighting NA-16

Two models of the NAA NA-16 were purchased by the CAC, and a contract to build a variant, under license, suitable for Australian needs was signed. The Australian version would be called the Wirraway, from the language of the Wurundjeri Nation of Aborigines meaning “to challenge” or “Challenger.”

The CAC also contracted to build the Pratt and Whitney R-1340 Wasp 600-horsepower engine. This engine gave the Wirraway a maximum speed of 220 miles per hour. CAC further contracted to build a Hamilton Standard constant speed forged aluminum propeller. CAC wanted to manufacture as much of the aircraft in Australia as possible in the event that in wartime the nation was cut off from suppliers in faraway Britain and the United States. The first Wirraways were made from largely imported components from NAA until the small local Australian foundries and manufacturers could tool up to make the parts at home.

Unlike the American version of the trainer, the Wirraway would be outfitted for war. It was fitted for gun mounts forward of the windshield for twin .303 caliber (7.7mm) Vickers machine guns, synchronized to fire through the propeller. Each gun had a removable magazine of 600 rounds. The .303 was the standard round of all British and Commonwealth rifles and machine guns, making resupply uncomplicated. Another .303 flexible gun mount was added for the observer/instructor to serve as a tail gunner. The plane was also fitted with hard points for a role as a light bomber.

Despite the mounted guns the Wirraway would be no match against the best Japanese fighter, the Mitsubishi A6M Zero, with its 950-horsepower engine and 331 mile per hour maximum speed. In addition to two .303 machine guns, the Zero also mounted twin 20mm cannons. The inline two-seat Wirraway was also much less maneuverable than the agile Zero.

The capabilities of the Zero were as yet unknown and unappreciated by the Western Allied military establishment. Rapid advances were being made in fighter technology. The war soon taught the lesson that a two-seat aircraft, while imperative for the trainer role and useful in reconnaissance, is a heavy burden for a fighter.

The First Wirraway’s

Production of the Wirraway was given top priority, and by July 1939, the first production aircraft were delivered to the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). The new plane was immediately tested in its new roles of pilot training, reconnaissance, antisubmarine patrol, bombing, and ground support. When war began in Europe that September, production and training speeded up. By December 1940, seven aircraft were being delivered every week, and by September 1941 a total of 45 Wirraways were coming off the production line each month.

The first five Wirraways off the assembly line were assigned to No. 12 Squadron, RAAF and sent to the backwater town of Darwin on Australia’s northwest coast to defend that lonely outpost. They arrived in Darwin on September 5, 1939, just as war in Europe was beginning.

A training accident in 1940 destroyed one Wirraway, killing its two crew members. It was soon replaced by another plane. When war started in the Pacific, Darwin had only five Wirraways. Nine more of them would be forwarded to Darwin.

Australia’s Pearl Harbor

Darwin’s primitive civilian airport at Parap was home to the first Wirraway advanced trainers of 12 Squadron. This group was known as A Flight. The nine new planes of the squadron were based at newly built Batchelor Field, 50 miles south of Darwin and known as B and C Flights. Training and patrols continued until February 19, 1942, when a powerful Japanese fleet of four aircraft carriers, all veterans of Pearl Harbor, launched 188 fighters and bombers toward Darwin.

As many as 54 Japanese Army planes flew from captured Dutch airfields on Ambon and Kendari to be the second wave of the Japanese punch. When the attack came, every plane in A Flight at Parap was grounded for service and repair.

Even if the Wirraways in Darwin were serviceable, they could not have intercepted the Japanese bombers because there was no efficient early warning and control system at the time. The radar equipment that had been sent to Darwin had not yet been assembled, and reports of incoming planes from coastwatchers were ignored. Darwin was caught completely by surprise.

Often referred to as Australia’s Pearl Harbor, the attack on the 19th killed 243 people and wounded 320 more. Much of the town was destroyed by bombs or exploding ordnance on the ground. Thirty-three ships in the harbor were sunk or damaged. Several planes on the ground were bombed, including two Wirraways of A Flight that were damaged badly enough to be written off. The Wirraways also lost much of their stores, ammunition, and spare parts when a nearby hangar was bombed and burned to the ground.

Distant Batchelor Field was spared from the bombing. Wirraways did not engage the enemy. However B and C Flights conducted post-raid activities, including locating and dropping supplies to survivors of sunken ships and stepped up patrol duties. The Wirraways continued serving at Darwin until mid-year when they began to be replaced in the fighter role by American-made Vultee Vengeance fighters. The Wirraways would continue in their training and patrol functions.

First Air-to-Air Combat

Wirraways were also busy elsewhere in the Pacific. In Malaya a squadron of the Royal Air Force departed to fight in the Battle of Britain. They were replaced by three squadrons of Australian planes and one from New Zealand. Two of the Australian squadrons were equipped with Lockheed Hudson bombers, while the third, No. 21 Squadron, flew camouflaged Wirraways painted with the squadron’s recognition letter “R.”

The 16 planes of 21 Squadron arrived in Malaya aboard the SS Orante in August 1940. A year later they were replaced by Americanmade Brewster Buffalo fighters. Ten of the Wirraways were crated and returned to Australia, while six were allocated to the RAF as trainers. They did not see combat, and all were lost in the chaos of the swift Japanese victory on the peninsula.

The Wirraway saw its lengthiest combat as a fighter above Rabaul on New Britain. The island had been a German colony prior to World War I. After the war it was allocated to Australia by the League of Nations as a trust territory. The port of Rabaul was formed by a collapsed volcano, open on one side, which created the finest deepwater port in the western Pacific. It was an obvious target for the Japanese, who controlled nearby Truk Island, also as a trust territory.

Australia took steps to defend the territory. Women and children were evacuated, ground troops were dispatched, and a wing of No. 24 Squadron was sent to Rabaul in early December. The squadron was under the command of Wing Commander J.M. Lerew. As the Australian planes landed at Lakunai airfield, Japanese reconnaissance planes flew overhead at high altitude and observed their arrival. The full complement of No. 24 Squadron included eight Wirraways and four Hudson bombers.

The first Japanese air raid came on January 4, 1942, around 10:30 am. Twenty-two Japanese bombers flying at 18,000 feet bombed the aerodromes and port facilities. Two Wirraways were scrambled to intercept them but could not catch them.

Nevertheless, the Wirraway pilots were confident in their abilities. The squadron’s second test came on January 6, when the Japanese made another attack on the town. Nine Kawanishi H6K Mavis flying boats zoomed in at 18,000 feet to bomb Vunakanau airstrip, which consisted of a single unpaved runway located 10 miles south of Rabaul.

Several Wirraways were scrambled, but only one, piloted by Flight Lieutenant B. Anderson could get close enough to fire a burst at the retreating floatplanes. Even then he was afraid of overheating his engine. Although none of the enemy planes were brought down, Anderson was the first RAAF Wirraway pilot to engage in air-to-air combat with the Japanese.

Futile Flight Against Zeros

On January 20, a coastwatcher on a nearby island reported seeing a flight of 22 enemy planes headed for Rabaul from the north. Another coastwatcher observed 33 more planes approaching from the west. Both flights were probably from Truk. Another 50 bombers and fighters remained undetected and were coming in from the east. These were launched by the aircraft carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku, both veterans of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

At the time, two Wirraways were in the air on standard patrol. The six others were scrambled while ground control still believed there was a single flight of 22 Japanese planes approaching. It was assumed that most of these would be bombers with a few escorting fighters. The Australians were outnumbered by more than 10 to one. The Australians quickly learned what the Americans already knew. The Zero was the best fighter in the Pacific Theater.

Japanese fighters intercepted the Wirraways. Three Australian planes were shot down, and two others crash-landed as a result of enemy fire. One other plane landed with part of its tail shot away. Just one emerged undamaged. No Zeros were hit. Six members of the squadron were killed and five wounded or injured that day, the worst but most gallant in Wirraway history. Only three of Lerew’s aircraft, one Hudson and two Wirraways, remained undamaged.

The next day the two remaining Wirraways left for Australia by way of Lae, New Guinea. The Hudson followed on the 22nd carrying the wounded. The Australian infantrymen at Rabaul were left to their fate. Few would survive the war.

The Only Zero Kill by a Wirraway

Not all of the Wirraways were playthings for the almighty Zero. On December 12, 1942, Pilot Officer J.S. Archer and his observer, Sergeant J.F. Coulston, became the instruments of the Wirraway’s finest hour. They were flying a tactical reconnaissance mission over the Gona-Buna battlefield on New Guinea to observe the wreckage of a Japanese ship sunk while trying to resupply the Japanese garrison at Gona.

When he returned to base at Popondetta airstrip (now Girua Airport), Archer rushed to find his control officer and excitedly told him that he thought he had shot down a Zero. He elaborated, “I went in to look at the wreck off Gona and I saw this thing in front of me [a thousand feet below] and it had red spots on it, so I [dived on it and] gave it a burst and it appeared to fall into the sea.”

The control officer calmly replied, “Don’t be silly, Archer, Wirraways can’t shoot down Zeros.” However, within minutes the officer received a dozen calls from observers on the battlefield confirming Archer’s story. He had shot down a Zero with his twin Vickers .303 machine guns. For his efforts the United States awarded Archer the Distinguished Flying Cross. It was the only time during the war that a Wirraway was victorious against a Zero. Archer’s plane survives today and is on display at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

“The Wirraway Pilots Never Received Adequate Credit”

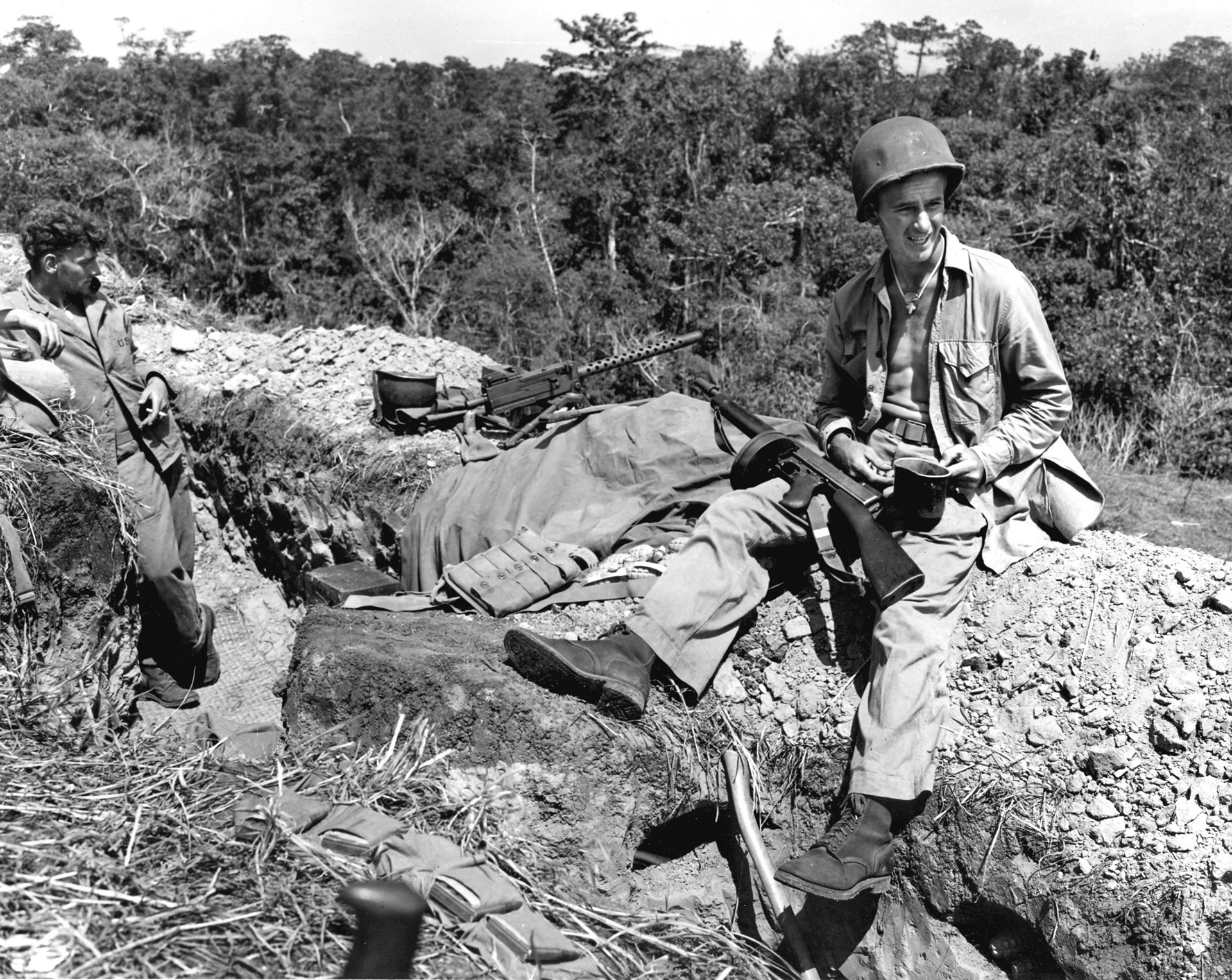

Archer’s victory was the high point of the Wirraway’s service during the war, but there were still everyday tasks to be done. By removing the second man from the plane, it could carry as much as 500 pounds of bombs, and in the New Guinea campaign it often carried out this duty. On December 11, 1942, a flight of six Wirraways took off from Popondetta, each carrying two 250-pound bombs to hit targets at Buna. Only five of them returned to base.

The Wirraway had other uses as well. At Popondetta, Archer was but one of the pilots who flew reconnaissance missions over the Gona-Buna battlefield. General Robert Eichelberger, commander of American forces at Buna, considered the Wirraway’s service particularly valuable. After the war he would write, “The Wirraway pilots never received adequate credit.” Eichelberger frequently hitched a ride in the tail gunner’s seat when he wanted to visit other areas of the front.

The attrition rate of the Wirraways was high, and when the last one was either shot down or lost in the jungle no American plane was forthcoming to fill the reconnaissance roll.

Several Wirraways were lost in combat. On January 1, 1943, according to the official record, “The aircraft crashed on a reconnaissance operation in the Gona area … Crew of two bodies discovered on 19/1/43 … by soldiers of the 2/18th Battalion Australian Army … Though the area was held by Japanese troops at the time of the forced landing, it is not sure if they were captured and executed, or were killed trying to evade capture….”

By February 6, 1943, the fighting at Gona-Buna had ended, so an air attack was unexpected when three Wirraways were damaged or destroyed on the ground during a Japanese bombing raid on Berry airstrip at Dobadura.

A Service History Marred by Accidents

During the early days of the war, several Wirraways were lost on the ground to Japanese strafing and bombing, but by far accidents caused the greatest loss to the Wirraway fleet. There were several causes of these accidents—design or manufacturing flaws, unfamiliarity with a new plane, pilot error, and engine failure all contributed to a high loss rate. Even minor ground accidents could put a Wirraway in the hangar for repairs.

On January 5, 1942, No. 7 Squadron had only 41 serviceable Wirraways out of 126 assigned to it due to accidents and servicing. In July 1942, No. 5 Squadron had 39 of its 100 planes waiting for new engines or engine service.

It was clear that the Wirraway was no match for Japan’s best fighter. By mid-1942 it began to be replaced by American planes with bigger engines, greater speed, and massive firepower. The CAC later produced an Australian fighter, the Boomerang, which had a more powerful engine, two 20mm cannons, and four .303 Vickers guns mounted in its wings. Wirraway partisans, however, like to point out that the Boomerang never brought down a Zero.

The Wirraway continued in its trainer, light bomber, sub hunting, and reconnaissance role for the rest of the war. The initial order for 620 aircraft was filled by June 1942, but limited production continued until 1946, when the 755th plane was completed.

In 1947-1948, a Wirraway was employed by the British Commonwealth Occupation Forces in Japan. The Wirraway continued in service with the Royal Australian Air Force as a trainer and communications aircraft until 1959. Today Australians are still proud of their first indigenously produced aircraft and the brave pilots who flew them in combat at a time when no other fighter was available.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments