by Richard Rule

Stripped of the regalia and high position of Reich Marshal in the Nazi regime and tried as a war criminal, the former Luftwaffe chief was by far the most colorful and outspoken defendant during the postwar proceedings.

At the end of World War II, Hermann Göring did not try to slip into hiding like many of Nazi Germany’s former leaders. In fact, he sought out the Americans on May 7, 1945, under the mistaken belief that he would be granted an audience with General Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Göring was confident that he would be treated as a spokesman for a defeated nation but, far from being an emissary for his people, he soon found himself regarded as a common prisoner of war. Flown to the modified confines of the Grand Hotel of Mondorf-Les-Bains in Luxembourg, he joined 50 other former Nazi ministers, officials, and high-ranking officers.

A Large Man in Poor Physical Condition

The Americans were surprised to find that Göring weighed over 260 pounds and was obviously in poor physical condition; he could have a heart attack at any moment. The Allies, who had already lost some key Nazi leaders to suicide, immediately put him on a strict dietary regime to reduce his weight and a withdrawal program to break his drug habit. Göring, a man who had enjoyed the fine life when in power, was hardly receptive to the prison fare put in front of him, but in time even he acknowledged that his health had rapidly improved.

As the inches vanished from his ample waistline and the fog of drug addiction cleared from his system, a rejuvenated Göring regained a mental drive and energy not evident since the early days of the party. In his self-imposed role of Primus inter pare at Mondorf, he called for a united front to shield Hitler from condemnation but, with little solidarity among the prisoners, his demands were completely ignored by most. There were those, however, who rallied behind the Reich Marshal, believing the affable Göring could perhaps negotiate their release. It was a forlorn hope, as most would soon find themselves indicted for war crimes.

No More Lenient Treatment

When the U.S. Army formalized the list of 22 principal defendants, Göring was delighted that his name appeared at the top, but others could not understand why their names were there at all. They still had not grasped that the lenient treatment afforded Germany’s leaders after World War I would not be repeated in 1945.

On August 12, Göring and the other accused men arrived in the shattered ruins of Nuremberg to stand trial. Bustled into the detention block alongside the Palace of Justice, the disorientated former leaders were thrown into small, spartan cells that were little more than low-ceilinged cubicles. Under the governance of the dour U.S. Army Colonel, Burton C. Andrus, security in the prison would be rigidly enforced. To this end, every conceivable device that could aid a suicide attempt had been removed; even the flimsy table provided to write letters and notes was designed to collapse under the weight of a small man.

Faced with a bleak and uncertain future, many of the inmates had great difficulty adjusting to these new surroundings. Even Göring’s indomitable spirit was temporarily dented by the unaccustomed squalor, but his will to resist had not diminished and he soon confounded prison authorities by steadfastly refusing to clean his cell. Threats and intimidation made no impression on him, and eventually Andrus was forced to have a prison employee carry out the menial task. In Göring’s opinion, even a small victory was better than no victory at all, and he was very proud to have ruffled the feathers of his captors.

At the Nuremberg Trials, Reich Marshal Hermann Göring Was a Difficult Man to Dislike, and to Question

In Nuremberg, the prisoners were interrogated in earnest prior to the trial, but Göring was the only defendant who willingly participated in these verbal jousts. The former World War I fighter ace, who had been at Hitler’s side since the 1920s, was not only an economic and military leader but also Hitler’s heir apparent. He expected to yield an invaluable insider’s perspective on Germany’s political and military strategies. His engaging manner, charm, and raw sense of humor appealed to many who questioned him and, despite his brutal reputation, most found it difficult to dislike him. However, he proved a difficult man to question.

Göring spoke quickly and a lot, but his answers were only couched in general terms. His questioners soon came to realize that he was no fool and certainly nothing like the ridiculous, comical figure portrayed in Allied newspapers. they, like many others, found Göring to be a very shrewd individual blessed with a keen intellect and worthy of wary respect.

Life in Solitary Confinement

The leaders of the Reich, he told his interrogators, were a group governed by common loyalties and a common ambition to revive German fortunes, and Hitler had held this unruly gang together by the force of his will. Göring was often the man who had the final word on most matters, not necessarily the first. Although cagey with specifics and often scant on details, Göring in no way diminished his role in the machinations of the Third Reich or his loyalty to Hitler’s vision of a greater Germany. Hitler’s once-faithful paladin did concede, however, that he had been against going to war with England and viewed the invasion of Russia as inevitable, but premature.

Life for the prisoners in the eerie silence of solitary confinement was harsh and soul-destroying. The gloom that pervaded through the cold stone walls of the detention block did not, however, appear to have washed over Göring. Much to the annoyance of the other inmates, he was often loud, habitually bombastic, and always defiant. The sight of the Reich’s former leaders submissively bowing to the will of their captors infuriated him. In his mind, adopting a visibly repentant demeanor would in no way help their cause before the court. They were already guilty regardless of their conduct in prison.

Resolute to the Last

It became a point of honor that Göring rarely took a backward step and would not allow a victor’s judgment on Germany to pass unchallenged. A comment condemning his nation’s wars of imperial conquest received a typically scathing reply: “Don’t make me laugh!” he roared, “America, England, and Russia have all done the same thing to promote their own national aspirations but when Germany does, it becomes a crime—because we lost.”

He aggressively dismissed the legitimacy of the proposed victor’s trial, going so far as to predict that the proceedings would “be [viewed as] a disgrace in 15 years time.”

Regardless of Göring’s vehement rejection of Allied jurisdiction, each prisoner was unceremoniously handed their formal indictment, which tabled the charges under the headings:

Count One: The Common Plan or Conspiracy.

Count Two: Crimes against peace.

Count Three: War Crimes.

Count Four: Crimes against humanity.

The lengthy document, running to some 25,000 words, set out in detail the unbelievable atrocities and crimes for which the defendants now stood accused. Göring was charged under all four counts, and while unsure of the journey, had no illusions about the fate that awaited him. Painfully aware that his name had become the butt of jokes and universal derision, he was determined that during this, the final chapter of his life, he would give his role at Nuremberg historical importance and restore prestige to his much-maligned reputation. It was imperative, in his view, that the people remembered that Hermann Göring had stood defiant to the bitter end and had gone to his death like a man.

In the shadows of the looming trial, Dr. Gustav M. Gilbert, a U.S. Army psychologist, had been given the task of observing the defendants and in Göring found a man who, in many ways, was a slave to his massive ego. He spent a great deal of time with Göring and warned the prosecution to expect an extremely aggressive and formidable opponent who would not be easily intimidated. Despite an imposing presence, Gilbert believed Göring’s Achilles heel would be the public revelations of the Reich Marshal’s bizarre vanities and ostentatious behavior. In his opinion, ridicule over, for example, the extravagant uniforms he designed for himself and his habit of wearing make-up would not only unsettle and embarrass Göring, but also “spoil his pose as a hero-patriot and model officer” in the eyes of the German people. He seemed more concerned about a tarnished image than many of the crimes committed by the regime he served.

The psychologist’s evaluation came as no surprise to the prosecution, which already knew that Göring would be difficult to handle. His unrepentant, egocentric behavior in prison gave every indication that he was spoiling for a fight. When the time came to cross swords, it would be essential in the court of world opinion that the U.S. chief prosecutor, Robert H. Jackson, quickly establish his superiority. This bare-knuckled battle of wills between Jackson, the wing-collared champion of human rights from Pennsylvania, and Göring, the flamboyant military gangster from the war-ravaged streets of Berlin, shaped up as the most anticipated moment of the trial.

Under the watchful eyes of the world media, the formal proceedings finally began on November 20, 1945. The former Reich Marshal, now at a much lighter weight, had taken a prominent position in the front corner of the dock. When asked to plead guilty or not guilty, he attempted to read a short declaration. After only a few words, he was firmly cut off by the British presiding judge, Sir Geoffrey Lawrence, who instructed him to plead guilty or not guilty, nothing more. A chastened Göring replied, “Not guilty, in the sense of the indictment,” then sat down.

The brilliant opening address by Justice Robert H. Jackson encompassed a devastating attack on the Third Reich. His confronting speech, delivered in a forthright manner, laid bare a vile catalogue of crimes whose responsibility, he pointed out, rested with most of those now sitting meekly in the dock. “It may be that these men of troubled conscience, whose only wish is that the world forget them, do not regard [this] trial as a favor,” Jackson declared. “But they do have a fair opportunity to defend themselves—a favor which these men, when in power, rarely extended [to anyone].”

Having to now answer for the crimes and unspeakable miseries inflicted on millions by the Third Reich left the men in the dock in no doubt that they would be lucky to escape with their lives. Incriminating the absent would soon become the order of the day.

Before the proceedings had begun, the tribunal had taken the controversial step of stopping the defendants from using a “so did you” defense strategy in regard to atrocities. Göring, nonetheless, was determined to reveal to the world that the Germans were not the only ones guilty of war crimes. However, this pre-trial boast to accuse the Allies of their own atrocities was soon demolished with the screening in court of the first graphic concentration camp films. The sickening images stunned not only the court but also many of the defendants, including Göring.

Worse was to come for the accused in the New Year when, on January 3, 1946, SS General Otto Olendorf described to the court in great detail the methods of mass execution employed by the Nazi death squads. These systematically organized murder operations were on a scale so incredible, so monstrous, they defied belief.

Göring was left deeply depressed when he realized that, in the wake of Olendorf’s frightful testimony and the horrific newsreel film, he would have no chance whatsoever of defending the party or the leader he had served for so many years. Yet, despite the fearful stories already revealed to the court, Göring greeted anything produced by the Soviets with biting sarcasm and studied ridicule; he considered the Russians to be the real experts in mass murder. On February 20, he yawned through a Russian atrocity film as it was being screened. “They could just as easily have killed a few hundred German prisoners of war and put them into Russian uniforms,” he observed cynically to an American officer. “You don’t know the Russians the way I do.”

The incredible passion and energy that had marked the opening of the trial soon became entangled in tedious legal procedures and argument that enveloped the proceedings like an impenetrable London fog. The public, which had reluctantly embraced the notion of a fair trial and not a long one, was becoming restless, bored, and disillusioned as weeks turned into months.

Göring, who regarded himself as the ranking officer among the prisoners, was also acutely aware of rumored disunity among the Allies. He steadfastly believed that the longer the trial continued the better chance there was of the four prosecuting powers falling out, and to this end he bullied and cajoled many of his co-defendants to bolster their will to resist. His constant haranguing during the lunch breaks became so serious that in February 1946 the controlling powers decided to isolate him, making him eat his meals alone in a dimly lit room away from the others. He took his banishment like a scolded schoolchild, but it was viewed as a favorable situation for the prosecution.

As Defendant No.1, Göring’s case was the first to be heard, and on March 8, 1946, his attorney, Dr. Otto Stahmer, called his first defense witness, General of the Air Force Karl Bodenschatz. As the Reich Marshal’s former liaison officer, Bodenschatz told the court of Göring’s role in peacefully resolving the Munich crisis in 1938. He also described Göring’s opposition to Hitler’s plans of going to war with Britain and the Soviet Union and how, on numerous occasions, he had intervened on behalf of individuals who had fallen foul of the Gestapo. It had been a tame, lackluster examination that had done little to dent the case against Göring.

Justice Jackson then rose to cross-examine the witness, and despite Bodenschatz’s valiant attempts to defend his former commander, Jackson tore the aging general’s testimony to shreds. The American prosecutor greatly impressed Allied observers with his powerful performance and sent a shudder through the defendants.

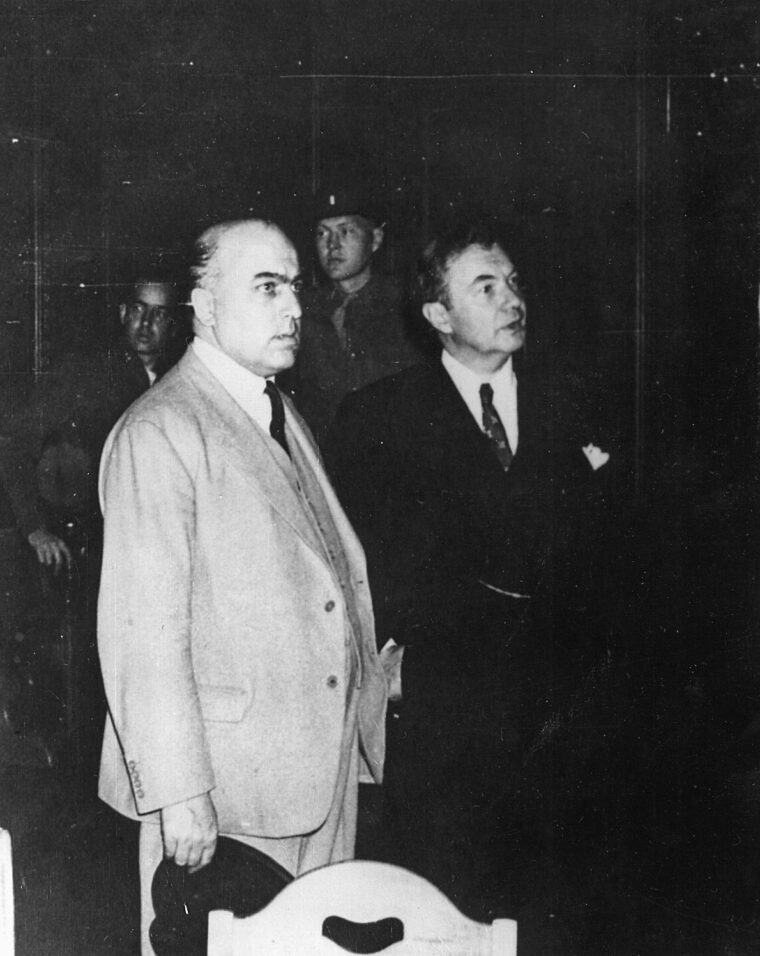

Stahmer’s next witness was the stocky Field Marshal Erhard Milch, who, although Göring’s deputy, had not been on the best of terms with his commander for a number of years. The prosecution (and Göring) believed that Milch was likely to provide damning testimony against the former Reich Marshal. As events unfolded, the Americans were to be bitterly disappointed.

Stahmer’s direct examination lasted barely 15 minutes and gleaned only that the Luftwaffe had been created purely as a defensive weapon, the contention being that Göring could not have been, therefore, planning to wage an aggressive war. It was a weak argument and carried little weight with the tribunal.

When Jackson commenced his cross-examination, he found that the field marshal was made of sterner stuff than the servile Bodenschatz. Milch, facing prosecution himself, parried every attempt by Jackson to gain damaging evidence against Göring and stepped down from the witness box having left a favorable impression of his former commander.

Three more defense witnesses were called, and their testimony also portrayed Göring in a favorable light as commander of the Luftwaffe. Unfortunately, it had not solely been his position as the head of the German Air Force that had put Göring in the dock, but rather his role behind many of the criminal policies of the Nazi Party. Had the Reich Marshal’s influence in the Third Reich been limited to his command of the Luftwaffe he would have been a great deal better off at Nuremberg.

Finally, after five months, the most anticipated moment of the trial arrived when, during the afternoon session of March 13, 1946, Göring finally left the dock and took the stand. With hair slicked back and eyes gleaming, Göring had an aura that touched nearly everyone in the packed courtroom, including the judges; the power he had once had, his influence over world events, and his confident, arrogant manner were mesmerizing.

In a predetermined strategy, Stahmer asked a lengthy series of concise questions, which allowed Göring to outline the pivotal role he had played in consolidating the rise of the Nazi party. It was clearly a point of personal pride to him that he had had such a decisive influence on Germany’s fortunes, and he unashamedly relished what he had achieved. He did not shy away from his involvement in Germany’s military buildup. “Of course we rearmed,’” he stated, “‘I am only sorry we did not rearm more.” He was in favor of seizing back the lands and territories Germany had lost under the Treaty of Versailles and actively supported reuniting Austria, Danzig, the Sudentland, and the Polish Corridor into the Reich—by force if necessary.

Untroubled by scruples, Göring argued that much of the indictment against him centered on internal political questions and, as such, were no business of any foreign court. and on the charges relating to war crimes and crimes against humanity, he was brief and vague. While intimating that he had strong reservations about some practices of the regime, he did not deny supporting judicial violence, having created neither the Gestapo nor establishing the first concentration camps for sequestering opponents of the Nazis.

He was quick to point out, however, that from 1934 these camps were under the control of Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler, and he had nothing further to do with them. He would state that neither he nor his leader had any idea how literally the SS had actually taken their orders for a final solution of the Jewish problem, and he, perhaps conveniently, shifted the responsibility for these mass murders onto Himmler.

Göring’s voluntary admissions and frank avowal, noble as they may have been, were hardly the basis for a sound defense, but he was in no mood to wash away his guilt or apologize for anything he had done. Despite at times inflating his influence over Hitler and embellishing his contribution to some of the key turning points of the regime, Göring cut an impressive figure in the witness box. His booming voice and defiant testimony, broadcast throughout the land by the Allies, actually lifted spirits in many parts of Germany as the people heard their “Hermann” fighting back.

Göring was subsequently questioned by 16 of the defense attorneys. They hoped that he would honor his pre trial promise to take total responsibility upon himself to lessen the guilt of their clients and improve their chances for an acquittal. Ironically, the very men who detested Göring now looked to him to minimize their influence on events and the importance of their duties. He tried to do this where possible but, for most, the Teutonic passion for fastidiously putting everything to paper had already sealed their fates.

The prosecution listened for two days with growing impatience as the Reich Marshal gave his version of Nazi history. They knew his testimony was full of holes and distortions and were determined to pull him into line and deflate his growing popularity. As Hitler’s deputy, they would attribute Göring with comprehensive knowledge of all the crimes committed by Nazi Germany, and Jackson planned to grill him on his anti-Jewish decrees and insatiable acquisition of stolen artwork. His aim was to not only portray Göring as a corrupt and deceitful officer, but also to expose to the world a direct link between the racial decrees he instigated and the wholesale mass murder of Jews that followed.

It was a sound strategy, but at the last minute Jackson decided to, instead, confront Göring with broad-ranging political questions, which he believed would furnish damaging admissions. This ill-advised change in strategy was to end in disaster.

Late in the morning session of March 18, Jackson stood to begin what most observers regarded as the heavy weight bout of the trial; it would not, however, deliver the telling blow that the controlling authorities had sought.

Jackson: “You are perhaps aware that you are the only man living who can expound to us the true purposes of the Nazi Party and the inner workings of its leadership?”

Göring: “I am perfectly aware of that.”

Jackson: “You, from the very beginning, together with those who were associated with you, intended to overthrow and later did overthrow the Weimar Republic.”

Göring: “That was, as far as I was concerned, my firm intention.”

The American chief prosecutor, adopting a lofty attitude, had hoped to make Göring squirm by outlining his direct involvement in the litany of broken treaties, deceitful foreign policies, and criminal activities of the Third Reich. Jackson, however, was completely wrong footed when Göring, far from evading his culpability, freely admitted it. Enjoying the theater of the moment, Göring unashamedly took great pride in telling or retelling the court, at length, exactly what he had done and why.

The American prosecutor grew increasingly frustrated as Göring skillfully balanced brutal honesty with self-effacing repartee that regularly attracted howls of laughter from the public gallery. Jackson was more accustomed to the American district court system where a hostile witness could be skillfully harassed and undermined with aggressive quick-fire cross-examination. At Nuremberg, the need to laboriously translate each question into German for Göring effectively nullified this weapon.

The latter, who had a firm grip of English, enjoyed a distinct advantage over his American adversary and used the translation time to carefully consider his answers. As Göring worked his audience, Jackson felt he was losing control of the situation and on one occasion demanded his witness answer a question with a simple yes or no. The presiding judge, however, intervened on Göring’s behalf, stating that he should be allowed to make whatever explanation he needed to properly answer the question. The humiliated prosecutor stood red-faced as Göring, who now felt he had the court in his corner, smugly continued his answer—at length.

Jackson had regarded the defendants as little more than common criminals and had easily handled the small fry dished up by the defense earlier in the trial. Göring, however, demonstrated repeatedly that he was anything but common. The open hostility between the two men was obvious to all, yet try as Jackson might to gain the ascendancy, he was often made to look ridiculous when Göring corrected factual errors and constantly highlighted inaccuracies within the many poorly translated documents tendered into evidence. No one had expected him to have such an immense knowledge and understanding of these documents. He would bring mistakes to the attention of Jackson in such a condescending manner that he appeared to be addressing a junior clerk of the court, not the American chief prosecutor.

The day’s adjournment could not come quickly enough for the hapless Jackson. The very public mauling he had received at the hands of Göring left him visibly distraught, particularly when he became aware of the sharp criticism his performance had received around the world. Patrick Dean of the British Foreign Office, for example, described the cross-examination as “very disappointing and unimpressive.” Reports from the press gallery were far more scathing.

It was incomprehensible to Jackson that after such a polished opening to the trial, his stock could plummet so quickly.

Albert Speer, Hitler’s former armaments minister, probably made the most telling observation of the affair to Dr. Gilbert: “You know, when Jackson cross-examines Göring, you can see that they just represent two entirely opposite worlds—they don’t even understand each other. Jackson asks him if he didn’t help plan the invasion of Holland and Belgium … expecting Göring to defend himself against a criminal accusation, but instead Göring says, why yes, of course, it took place thus and so, as if it is the most natural thing in the world to invade a neutral country if it suits your strategy.”

The following day, March 19, the battle resumed, but by late in the morning session it was clear that Göring once again had Jackson’s measure. The American was repeatedly called to order and often ensnared in traps he had actually set for Göring.

Matters finally came to a head during a widely publicized exchange over the Nazis’ secret prewar plans to occupy the Rhineland. Jackson, trying to establish the devious nature of these preparations, described them as being “of a character which [was] kept entirely secret from foreign powers.”

Göring sarcastically replied: “I do not think I … recall reading beforehand the publication of the mobilization preparations of the United States.” The court erupted in laughter, and an infuriated Jackson threw down his headphones in frustration.

In a voice faltering with rage, Jackson addressed the judges: “I respectively submit to the tribunal that this witness is not being responsive and has not been in this examination … [Göring’s] arrogant and contemptuous attitude toward the Tribunal … is giving him the trial which he never gave a living soul, nor dead ones either.” He considered that the tribunal was allowing the impudent and argumentative Göring far too much leniency and his obstructive tactics would “encourage all the defendants to do the same thing.”

Bitter and defeated, Jackson considered abandoning the cross-examination altogether. The British prosecutor, Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe, argued strongly against such a move, for history would not judge them kindly if Hitler’s former deputy was seen to have got the better of the best legal team the Allies could muster. The robust Maxwell-Fyfe, who had vast experience dealing with the likes of Göring, took over the cross-examination with the aim of decisively regaining the initiative.

Göring listened intently as the Englishman went straight to the attack over the former Reich Marshal’s involvement in the Gestapo murder of British airmen who had escaped from a POW camp in Sagan. Maxwell-Fyfe was well versed on the circumstances surrounding these murders; Göring was not. The British barrister’s incisive questioning on the incident brought beads of sweat to Göring’s brow, and his evasive answer that he was on leave at the time of the shootings was unconvincing and made little impression on the court. It was the low point of his testimony.

Maxwell-Fyfe’s skillful and relentless cross-examination failed to directly connect Göring with the murders, but he had, much to the relief of the prosecution team, publicly knocked the German off his lofty perch.

Göring was visibly rattled as the prosecution highlighted his connection to what ultimately came to pass as the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question.” The dialectical eloquence and broad-brush recollections that had served him so well earlier were now repeatedly contradicted by irrefutable documentary evidence. The further the proceedings went on this subject, the less impressive Göring became as the vast majority of documents received into evidence provided ample proof of his complicity.

Maxwell-Fyfe eventually asked Göring if, in light of all that had been revealed about the horrors of the Nazi regime, he was still loyal to Hitler. A hush fell over the court. This was a question with far-reaching consequences, and Göring knew it. Choosing his words carefully, he replied that he believed in being loyal in good times and in times of hardship. Hitler, he declared, had more than likely known as little about the atrocities as he had himself. In a revealing observation, Göring later assured Dr. Gilbert that the Allies need not worry about the Hitler legend living on: “When the German people learn all that has been revealed at this trial, it won’t be necessary to condemn him: he has condemned himself.”

The success of Maxwell-Fyfe’s and of the Russian Chief Prosecutor, General R.A. Rudenko, had been achieved through a willingness to allow incriminating documents to do the talking for them. Rudenko, for example, was blunt and to the point and would simply show Göring documents that were already in evidence, then demand that the witness acknowledge his complicity in the crimes they disclosed.

Göring and Rudenko understood each other well and battled like two prize fighters squaring up privately outside the ring, typified in selected portions of the following exchange: Rudenko alleged that the German attack on Russia had as its primary aim the complete annexation of most of the western Soviet Union as stated by Hitler during a conference on July 16, 1941. Göring was present at this meeting but under Rudenko’s cross-examination denied having agreed with talk of annexations because, in his view, the war in Russia had not yet been won. The record then continues.

Göring: “[I did not mean] ‘I protest against the annexation of the Crimea [or the] Baltic States.’ I had no reason to do so [but at] that moment we had not finished the war …

Rudenko: “In that case, you considered the annexation of these regions as a step to come later … after the war was won.”

Göring: “[Being] an old hunter, I acted according to the principle of not dividing the bear’s skin before the bear was shot.”

Rudenko: “I understand. And the bear’s skin should be divided only when the territories were seized completely, is that correct?”

Göring: “Just what to do with the skin could be decided … only after the bear was shot.”

Rudenko: “Luckily, this did not happen.”

Goring: “Luckily for you.”

Rudenko then wisely concentrated heavily on Göring’s driving influence behind the forced labor program, which had been brutally implemented in the conquered territories. From these exchanges, he drew very explicit admissions from Göring, who did not deny his culpability in this area. These acknowledgments proved to be the foundation for his conviction under counts three and four (war crimes and crimes against humanity) of the indictment.

In the main, Göring’s days in the witness box provided an incredibly lucid and often enthralling insight into the workings of the Third Reich. Yet, despite his candid and masterly performance, most found it incomprehensible that he could now, in defeat, plead total ignorance of the horrors of which he surely must have known or at least suspected. In many respects, his position appears consistent with a leader who, only concerned that his armies succeeded, deliberately avoided learning of the unpleasant methods his forces would employ in achieving victory.

The Göring case had taken up over 12 days of court time, and as the trials of the other defendants continued, few managed to capture world attention the way Göring had. He sat through the remainder of the trial, appearing at times to be either totally disinterested or completely disgusted when his codefendants shamefully incriminated each other, shuffled off blame to subordinates, or claimed documents were forged. It struck some observers as ironic that in defeat many prisoners had denied involvement in events for which, had Germany triumphed, they would have undoubtedly clamored for recognition.

Many would feel Göring’s icy stare as they desperately tried to save their skins by selling out, but he reserved special loathing for German prosecution witnesses who were paraded through the courtroom to provide often damning testimony against the accused. “These boiling fowls,” he cynically observed, “will be allowed to cackle [and] lay an egg for the Americans and then they too will go into the big pot [with the rest of us].”

Göring’s rage spilled over, however, when Field Marshal Friedrich Paulus, the commander of the Sixth Army captured at Stalingrad, appeared on behalf of the Russians. “Ask that dirty swine if he knows he’s a traitor,” he roared to his defense attorney.

With the press already laying bets on who would be hanged, this unique and mammoth trial was coming to its climax. Justice Jackson, who regained his proper form as the trial continued, gave what many authoritative lawyers regard as the greatest summation ever delivered at a criminal trial. In closing, he stated: “If you were to say of these men that they were not guilty, it would be true to say there has been no war, there have been no slain, there has been no crime.”

On August 31, after 216 court days, 300,000 documents, and over 10 million words, the accused were called upon to make their final addresses. As defendant No. 1, Göring spoke first, and his statement mirrored the sentiments of most of those alongside him in the dock. “The prosecution, in the final speeches, has treated the defendants and their testimony as completely worthless … statements made under oath were accepted as absolutely true when they could serve to support the Indictment, but conversely the statements were characterized as perjury when they refuted the Indictment.”

Condemning the mass murders to the utmost, he claimed, “He [Hitler] had never decreed the murder of a single individual at anytime and neither did I decree any other atrocities or tolerate them. The German people trusted the Führer … Ignorant of the crimes of which we know today, the people have fought with loyalty, self-sacrifice, and courage, and they have suffered, too, in this life-and-death struggle into which they were arbitrarily thrust. The German people are free from blame.”

Tuesday, October 1, 1946, was judgment day. when addressing the case against Göring, the president of the court, Sir Geoffrey Lawrence, described his guilt as “unique in its enormity… [for which] … the record discloses no excuses. There is nothing to be said in mitigation,” he continued, for Göring was often, indeed almost always, the moving force second only to his leader. He was the leading war aggressor, both as political and as military leader; he was the director of the slave labor program and the creator of the oppressive program against the Jews and other races at home and abroad.”

Göring was pronounced guilty on all four counts of the indictment, and everyone watched for his reaction, but other than to shake his head, he showed not a hint of emotion. At 3 pm that afternoon, he entered the courtroom alone to hear his sentence. Sir Lawrence came straight to the point. “Defendant Hermann Wilhelm Göring, the International Military Court sentences you to death by hanging.”

On October 4, Göring’s defense lawyer, against his client’s wishes, formally petitioned the court control council to commute the death sentence or at least change it to a firing squad. Predictably, the motion was denied.

Despite security being tightened following sentencing, Göring was allowed one last visit from his wife on October 7. It was a highly emotional moment in which the two managed to say their farewells with dignity. He would not be hanged, he calmly assured her before she was whisked out of the room. Back in his cell, an anguished Göring confided to the prison doctor, “I’ve seen my wife for the last time … now I am dead.”

During the night of October 13, the defendants could hear trucks loaded with gallows equipment arriving at the prison yard, closely followed by the sounds of construction. On the night of October 15, with the prison block bathed in light, the prisoners suspected their executions were imminent.

At 8:30 that evening, Göring was observed lying on his cot reading a book, still bitterly disappointed that he had not been allowed to die by firing squad and annoyed that he had been denied the last rites for showing no sign of repentance. He had somehow obtained a cyanide capsule which, at about 10:40 pm, he slipped into his mouth and bit down. Pandemonium broke out as doctors rushed to his cell and tried desperately to revive him, but it was too late. The 53-year-old Hermann Göring was dead. It is generally believed that either Göring had the poison with him all the time or that a third party inside the prison, perhaps a guard, had smuggled the cyanide into his cell.

Among the letters found in his cell was the following:

“I find it tasteless in the extreme to stage our deaths as a show for the sensation-hungry reporters, photographers, and the curious. This grand finale is typical of the abysmal depths plumbed by the court and prosecution. Pure theater, from start to finish! … I understand perfectly well that our enemies want to get rid of us—whether out of fear or hatred. But it would serve their reputation better to do the deed in a soldierly manner. I myself shall be dying without all this sensation and publicity…. I feel not the slightest moral or other obligation to submit to a death sentence or execution by my enemies and those of Germany. I proceed to the hereafter with joy, and regard death as a release.”

News of Göring’s suicide spread throughout the world like wildfire, but in the wider German community, reports that he had cheated the hangmen’s noose were generally greeted with delight. In death at Nuremberg, as in life, many were pleased to know that Göring had had the last word. Vainly conscious of his historical image, he believed that his uncompromising defiance in Nuremberg would see him revered as a hero of the German nation and his body entombed in a marble sarcophagus like Napoleon’s.

In a last letter to his wife, Göring wrote: “In 50 or 60 years there will be statues of Hermann Göring all over Germany. Little statues, maybe, but one in every German home.”

For Göring, the posthumous rehabilitation he craved would not be realized. He had, without doubt, risen to impressive heights in the witness box at Nuremberg; the popularity and respect he had earned, however, were only fleeting. When, in the months following the trial, the true extent of the Third Reich’s murderous legacy became known to the wider German population, Göring and the other Nazi leaders were regarded with revulsion.

Hermann Göring may well have denied his captors their pound of flesh, but the passage of time has deemed his true punishment to be that history would forever condemn him as a key conspirator in one of the most malignant regimes the world has ever known.

Richard Rule writes from his home in Heathmont, Victoria, Australia. A veteran of the Australian Army, he works in sales management, enjoys fly fishing, and has written several books.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments