By Martin Leavitt

It was raining, raining with a force and intensity few had ever experienced. The Macedonian army was marching upstream near the northern banks of the Hydaspes River in India (now Pakistan), trying to reach a ford under the cloak of darkness. The year was 326 b.c., the month probably May, and the Macedonians were in the latter stages of a campaign that, with some brief interruptions, had lasted almost eight years.

The rain came down in sheets, the droplets driven by howling gales, and lighting danced and crackled across the sodden skies. The bolts thundered and pealed, causing the rain to fall even heavier, as if the very floodgates of heaven had been rent asunder by the booming reports. The soldiers must have been soaked to the skin, wrapped in cloaks that were so wet protection was minimal.

Alexander of Macedon, later known as Alexander the Great, was in the van of the army, sharing as usual the discomforts as well as the glories of war. He was probably pleased that the night was so stormy; Zeus the Thunderer was plainly coming to Macedonian aid. Just across the river a large and formidable Indian army under Rajah Porus of the Pauvaras was trying to block the Macedonians from crossing. The violent storm, coupled with the pitch-black night, would screen Alexander’s movements from the prying eyes of enemy scouts. Yet inclement weather alone could not insure battlefield success. Would the Macedonian king’s nocturnal maneuver be crowned with success?

Alexander Lauded For His Military Timing & Tactics

Alexander III of Macedon, in Greek Alexandros III Philippou Makedon, is without question one of the great captains of military history. He certainly looked the part of a hero. Alexander was handsome, with even features and a flowing mane of blond hair. He had one blue eye and one brown eye, though the startling contrast in no way altered his basic appeal. He was athletic and tough, and though he was shorter than average his charisma made him seem larger than life. Alexander was courageous, yet rarely, if ever, foolhardy; he usually looked before he “leaped.”

Some historians, eager to debunk the legend, have tried to downplay his military talents by attributing his victories to subordinates. It seemed inconceivable to them that military genius could dwell in one so youthful, yet he began to command armies at 16. Even when elements of the legend are stripped away the facts speak for themselves: Alexander the Great was a military genius. He had a keen eye for terrain, a good sense of timing, and a solid knowledge of tactics. Above all he was adaptable, able to alter his plans to reflect changing circumstances. If he had one fault it was his tendency to unduly expose himself to danger and fight like a common soldier—a trait that nevertheless endeared him to his men.

Greek Coalition Defeated; Macedonia Rises

In the fourth century b.c. Macedonia was a state just to the north of Greece. Its population was an amalgam of several peoples, with at least some infusion of Greek blood. Its language was a reflection of this polyglot nature; Macedonian had Greek elements in it, but was so diluted with “barbarian” words most Greeks could not understand it. Nevertheless, Macedonia did have a patina of Greek civilization and was Helenized enough for its athletes to be accepted as competitors in the Olympic Games. Certainly, both Alexander and his father Philip II were strong admirers of Greek culture.

Philip II laid the foundations of Macedonia’s greatness. At the battle of Charonea in September 338 b.c., Philip defeated a coalition of Greek states that included Athens. Although he granted them a measure of autonomy, Philip made it clear that Macedonia would not stand for the bickering and fratricidal bloodshed that had been a hallmark of Greek politics for decades. Philip imposed peace and unity on Greece by forcing all Greek states save Sparta to join a Macedonian-dominated League of Corinth.

Alexander Assumes Crown After Assassination

Philip now looked across the Aegean to the Persian empire, long an enemy of the Greeks. In fact, in 490 and 480 b.c. Persian kings had invaded Greece in an attempt to make the country part of their empire. They failed, but the enmity between the two cultures remained. Philip proposed to invade the Persian empire, his first goal to liberate the Greek city states in Asia Minor. But Philip was assassinated in 336 b.c. at the age of 46 before his plans could reach fruition. Alexander, a young man who had shown his mettle in battle but was still only 20 years old, assumed the crown.

There was no question that Alexander would pick up where his father left off. In the fourth century b.c. conquest did not need to be justified, and Macedonian kings were expected to be warriors. Alexander was bursting with ambition, eager to make a name for himself. His old tutor, the Greek philosopher Aristotle, instilled in Alexander a love for all things Hellene. Conquering the Persian empire would fulfill his personal ambitions and satisfy a desire to the “avenger” of Greece.

Alexander’s army crossed the Hellespont into Asia in the spring of 334 b.c. It was the beginning of an odyssey that would conquer an empire and travel to the farthest limits of the known world—the known world, that is, of Greek classical civilization. In the battles of Granicus (334 b.c.), Issus (333 b.c.) and finally at the climatic battle of Gaugamela (331 b.c.), Alexander defeated the armies of King Darius III. When Darius was murdered by his own men Alexander’s victory over the Persians was complete.

The Indian Expedition

But once started, conquest can be a kind of addiction, a process that can prove an irresistible temptation. At least, it seemed to be so in Alexander’s case. The eastern provinces of Bactria and Sogdiana had been only loosely attached to the old Persian empire; Alexander decided to go there to make sure of a firmer connection. After some time in Bactria and Sogdiana, the Macedonian king was determined to go to India. Perhaps he wanted to follow in the legendary footsteps of Dionysus and Heracles (Hercules); the Macedonian royal family claimed descent from Heracles.

Maybe Alexander was motivated by a desire to explore the unknown. The Macedonian king believed, as did most educated people of the classical times, that the land mass of Europe and Asia was surrounded by a great body of water known as the Ocean Stream. In Greek thought, Europe and Asia were a giant “island” set in the vast ocean. Alexander wanted to see the Ocean Stream with his own eyes, at the same time setting the boundary of his empire to the edge of the world.

Apparently Alexander gave considerable thought to this Indian expedition and planned accordingly. Before this time most soldiers wore corselets/cuirasses; now they were being discarded, presumably for greater ease and mobility. Yet the change was probably not universal; some units or even individuals most likely maintained the old armor, even if it was hot and cumbersome.

Seeking To Bridge The Indus

The Macedonian army’s initial objective was the region around the great Indus River, in the area that today is generally called the Punjab. The Indus is one of the world’s great rivers and a cradle of civilization. It rises in the Himalayas then continues some 1,700 miles before emptying into the Arabian Sea. The Indus has four tributaries, which the Greeks called the Hydaspes, Acesines, Hydraotes, and Hyphasis. (Today they are the Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, and Beas.) The region was poetically dubbed the “land of the five rivers,” but to Alexander and the Macedonians waterways were barriers to overcome, not objects of romance.

Alexander sent his subordinate Hephaestion ahead to the Indus while the king himself dealt with troublesome hill tribes. Hephaestion began bridging the broad Indus in anticipation of Alexander’s arrival with the main body. Little is known about how the Macedonians bridged the Indus, but Arrian, a Greek writer who lived in Roman times, suggested a bridge of boats. The bridge consisted of a line of boats or galleys placed side by side with a roadbed on top.

In the meantime, Alexander started to march toward the Indus, en route giving orders to have trees felled for the construction of boats. Luckily, there were trees not far from the river that yielded high-quality lumber, and before long boats and galleys were sliding into the brown river waters. Meanwhile, Hephaestion completed the bridging of the Indus, a major engineering feat and the start of a new phase in the campaign. Alexander marked the occasion with sacrifices to the gods, athletic competition, and displays of horsemanship.

A New Foe Emerges On The Eastward March

The ceremonies over, Alexander crossed the Indus and marched on Taxila, a kingdom between the Indus and the Hydaspes rivers. The ruler of Taxila, whose real name was probably “Amphi,” was dubbed “Taxiles” by Alexander as a kind of dynastic title. Amphi/Taxiles proved a good friend to Alexander, allowing the Macedonians to rest and refit. Taxila was the crossroads of several trade routes to Bactria, Casmir, and the distant Ganges River valley.

Alexander was not unmindful of Taxiles’s support and rewarded the Indian prince with additional territory. Northwestern India was a patchwork of kingdoms, and several rulers sent representatives to treat with the Macedonian king. Porus, king of the Pauravas, failed to send an envoy. In fact, such an ambassador was conspicuous by his absence. It was then the truth must have dawned, and the reason for Taxiles’s eager friendship made clear: he and Porus were bitter enemies. Taxiles hoped to enlist Alexander’s aid in the feud. The Macedonian was more than happy to oblige; he wanted to go further east, and Porus’s kingdom blocked the way. If Porus could not be coaxed into an alliance, Alexander was more than ready to go to war.

Porus’s kingdom lay beyond the Hydaspes, which in the spring of 326 b.c. was a barrier of major proportions. Melting snows from Himalayan peaks combined with heavy rains to transform a placid, meandering stream into a foaming, raging torrent filled with treacherous currents. Porus stationed his troops along the southern bank, in essence using the river as a gigantic natural moat to protect his realm. The rajah paid particular attention to the fords, posting soldiers to make sure that, even if Alexander was lucky enough to thwart the forces of nature, he would not succeed in establishing a toehold on the south bank.

Preparing For War

Alexander established a base camp on the banks of the Hydaspes just opposite Porus’s own camp across the river. The Macedonian camp was plainly visible to the Indians, but Alexander purposely chose the site so he could be observed. Although acutely aware of being watched, the Macedonians nonchalantly set up their tents, prepared food, and undid bed rolls for sleep. Alexander’s army was a multinational force composed of many peoples. There were various Asiatics and even Indian soldiers from his new allies. Greek mercenaries were there, distinctive because of their full beards; Macedonians were clean shaven by Alexander’s express orders. The Macedonians were the heart of the army, and Porus must have had some curiosity about the appearance and habits of his new foes.

Years of almost constant campaigning had taken their toll on the men’s clothes and equipment. Many were shabby, their tunics threadbare and worn, and replacement Greek dress was hard to come by. Some recut Indian garments, some adopted Persian dress, and some mixed national styles in a “crazy quilt” fashion that must have amazed enemy observers.

The Toughest Battle of Alexander’s Career

Alexander knew he faced a challenge, one of the greatest of his career. The river was well-nigh impossible to cross in its present state, yet he couldn’t wait until winter reduced the waters to fordable levels. Even if he did attempt a crossing, Porus had a weapon that might tip the scales against the Macedonians: war elephants. The rajah had 100 to 200 of these great beasts (accounts vary), and their size and loud trumpeting usually terrified horses which were not used to them. The Macedonian cavalry was one of the key elements to Alexander’s success; elephants might neutralize this advantage. In truth, the elephants were also a terror to men as well as horses. A way had to be found to deal with them.

Yet time was running out, and delay might be fatal to the Macedonian cause. A Rajah Abisares of Casmir seemed about to join Porus against Alexander, and his army was as least as large as that of the Pauravan king. If the two rajahs united, Alexander might well find himself in serious difficulties.

A Cat-And-Mouse Game With Porus

For the next few weeks Alexander played a kind of cat-and-mouse game with Porus, doing all he could to deceive the Indian and keep him off balance. Macedonian troops were in constant movement, with detachments probing up and down the river as if preparing to cross. Since it was well known that Alexander was usually with his assault troops, the king resorted to a double to mask his personal movements. Attalus, a soldier who bore a striking resemblance to Alexander, walked about the royal pavilion and around camp when the king was not present. For days on end Macedonian cavalry would be seen at various points, as if a vanguard to a major crossing attempt, yet when Porus sent troops to the threatened sectors, the Indians would find their adversaries had disappeared.

Moving On His Complacent Foes

Porus must have been frustrated and baffled. Macedonian soldiers would march up and down making as much noise as possible, trumpets blaring, men shouting war cries and oaths. Finally, after several weeks of such maneuvers, the Indian king began to relax his guard. His troops were exhausted, worn out by trying to counter Alexander’s feints. Perhaps Porus began to think that Alexander’s movements were mere bluff, designed to conceal the fact that the Macedonians were going to wait for the winter and the river to recede. In fact, Alexander himself mentioned he would wait until winter, knowing such announcements would find their way back to Porus.

Alexander had no intention of waiting until winter, but decided on crossing the Hydaspes at night, right under the very noses of the Indians. Indian scouts’ senses, dulled by false alarms, were so inured to the sounds of enemy troop movements they would scarcely notice the noise of a crossing—or so Alexander hoped.

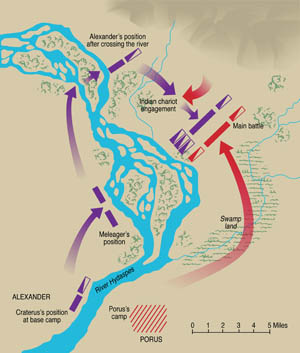

The crossing of the Hydaspes was a masterpiece of maneuver and a fitting prologue to the subsequent battle. Alexander outlined his plans during an emergency conference that was held probably in his royal pavilion. As previously mentioned, the king had decided on a surprise night crossing and, once on the southern bank, hoped to defeat Porus before Abisares could come up. Craterus was left in command of the base camp with about 2,000 cavalry and 9,000 infantry. Porus was still in camp with nearly his whole army, but once he realized Alexander was on the move he was sure to follow.

The Macedonians Hide Their Forces On Island

Alexander told Craterus not to cross the river unless Porus had moved his whole army upstream, or he was sure the Macedonians had been victorious. The Macedonian king now moved upriver, his goal a point just opposite Adamana Island. Alexander hoped to use Admana as a giant shield against the eyes of Porus’s scouts. He’d embark his strike or turning force on galleys behind the island, then go downstream with Admana to his left still blocking the Indians’ view. The Macedonian flotilla would round the tip of Admana and go ashore on the southern bank beyond.

En route to the crossing place Alexander detached Meleager, Attalus, and Gorgias with some 1,000 cavalry and 16,000 infantry about halfway between the base camp and Admana Island. Like Craterus, the trio were ordered to cross the river only if they determined Porus was occupied, that is, engaging Alexander. Now Alexander’s foresight and careful planning began to reap rich rewards. Some weeks earlier he had dispatched one of his officers, one Coenus, to the Indus with orders to bring back the galleys and boats the Macedonians had used there. To accomplish this task the galleys were cut in three sections, the smaller boats in two sections, and their pieces transported by wagon to the Hydaspes and reassembled.

The Long March To Admana Island

Alexander’s march to the Admana Island area assembly point took him inland, but the snaking course of the Hydaspes made the route a kind of shortcut. It must have taken hours for the Macedonian strike force to reach the assembly point; one historian estimates the 17- or 18-mile journey must have taken at least six hours under monsoon rain conditions. When the king arrived he found the oared galleys and boats waiting for him. Everything was falling into place; in addition to the troops under Meleager already mentioned, Alexander had posted small detachments all along the river, a “chain of communication” that linked him with the base camp under Craterus some 18 miles away. Signals could be relayed via trumpet calls.

Estimates of troop numbers should always be approached with caution. Ancient authorities rarely agreed, and modern historians usually rely on what are essentially educated guesses. According to one historian, Alexander’s initial strike or turning force—the one he was going to lead over the river—initially consisted of some 16,000 men. After Alexander crossed with the vanguard, more troops followed.

Estimates of troop numbers should always be approached with caution. Ancient authorities rarely agreed, and modern historians usually rely on what are essentially educated guesses. According to one historian, Alexander’s initial strike or turning force—the one he was going to lead over the river—initially consisted of some 16,000 men. After Alexander crossed with the vanguard, more troops followed.

The most notable unit in Alexander’s force was the royal squadron (Basilike ile) of the elite Companions (hetairoi) cavalry, known also as the agema or Royal vanguard. Alexander himself wore the striking purple tunic and cuirass of a senior Companions officer. The royal agema was supplemented by the hipparchies (cavalry unit, from the Greek word hippus, horse,) of Hephaestion, Perdiccas, and Demetrius. Each hipparchy had about 1,000 horsemen. There were also allied cavalry of Bactrians, Sogdians, and hard-riding Dahae archers and Sythians. Alexander’s infantry consisted of two phalanx pike units under Coenus and Clitus, some hypaspists (probably light troops) and various Asiatic allies. The king must have been eager to reach the southern bank of the river; if Porus caught the Macedonians in the act of crossing, or even partly across, the results could be disastrous. Large wooden rafts were constructed and given added buoyancy by attaching straw-filled watertight skin floats. The cavalry would be transported on these rafts, a delicate and time-consuming operation as well as a vulnerable one. If Porus’s war elephants appeared as the horses were embarking or disembarking, utter chaos might ensue. Even if they were still on the rafts midstream, the horses might still try to drive into the river if they heard or saw the elephants or caught their scent.

Flotilla Moves Seen By Indians

The flotilla set out before dawn, Alexander leading the way in a 30-oar galley that was towing a cavalry raft. Some of his closest personal companions were with him on the galley, including Ptolemy, son of Lagos. Ptolemy, later ruler of Egypt, left an account of the Indian campaign that was a source for later historians.

Dawn finally broke over the eastern horizon; the rain storm had abated, and the discomforts of the night must have been forgotten in the excitement and anticipation of battle. As planned, Admana Island blocked the view of the Macedonian fleet from the river shoreline, but once Alexander’s galley nosed around its western tip, the vessel was spotted by Porus’s scouts. Mounting their horses with alacrity, the scouts galloped back to their rajah with the news that the Macedonians were at last on the move.

Macedonians Make It To The Shore

Alexander was first ashore and started to supervise the disembarkation of his men. But it was soon discovered that the Macedonians were not on the southern bank of the river, but only on another island! This long finger of land ran parallel to the real southern bank and from a distance blended with it. As seen from the Macedonian side of the river, there was not the slightest hint it was an island. This was a major setback for the Macedonians, a crimp in what had been so far a flawlessly executed operation.

The channel between the real southern bank and the island was narrow, but also deep with treacherous currents. A passable ford was found, and the hapless Macedonian troops had to wade across it with water up to their shoulders. Even the horses had a rough time of it, the water coming up to their necks. It must have taken several hours to cross the ford, precious hours where Porus could have regained the initiative and attacked Alexander when he was at his most vulnerable. Timing is everything in war, and rarely are generals given a second chance. Porus missed this golden opportunity, and Alexander managed to get his entire force safely on shore.

Porus’ Son & Macedonian Forces Colide

Knowing that Porus’s army was somewhere downstream, Alexander led his cavalry south at a rapid pace, ordering the infantry to follow as best they could. Porus had indeed received the reports of a Macedonian crossing, but it still seemed that Alexander’s main force (really just Craterus) was still encamped across the river. Puzzled, Porus decided to send his son (some say brother) with a reconnaissance force of cavalry and chariots to see what was going on upstream. Was this crossing Alexander’s main force, or merely a diversionary feint?

This Indian scouting force consisted of some 2,000 cavalry and 120 chariots, far too little to deal with Alexander had they known he was there. The Macedonian king drew rein at the sight of the cavalry and chariots, uncertain if this was the van of Porus’s whole army. When he determined it was a detached force, Alexander led his Companions cavalry against Porus’s son. The chariot was obsolete tactically, and the Indian cavalry was no match for battle-hardened Macedonian troops.

Alexander Defeats Detached Force

Alexander’s horse archers unleashed showers of arrows into the chariots, killing and wounding drivers and warrior passengers with random impartiality. Each Indian chariot must have made a good target, for these large fighting platforms held six men—only two of whom had shields. The horses that drew the chariots were probably also hit with these lethal shafts, and once a horse was down in harness, that chariot was rendered instantly immobile. Once the charioteers were “softened up” by the archer’s stinging shafts, Alexander moved in with his Companions cavalry to finish the job.

The Companions cavalry moved forward at a gallop, the soldier’s purple tunics blending to form an undulating purple band across the horizon. Purple and yellow cloaks billowed behind them, and each soldier was wearing a bronze helmet in the Boeotian style, with a large curved “floppy” brim that gave the wearer an excellent field of vision. Although often depicted as bare headed for artistic purposes, Alexander himself often wore a Boeotian helmet. The members of the Companions cavalry were superb horsemen. They had to be; the ancients did not have stirrups. Each Companion cavalryman wielded a xyston, a long lance that featured a spear point on both ends. Made of sturdy cornel wood, it nevertheless frequently shattered in battle. That is why there was a spear point on both ends; if a lance shattered, a cavalryman could quickly reverse the haft and fight on.

The Indian charioteers were hard put to mount an adequate defense. Not only were Alexander’s men pressing on all sides, but the chariots had lost their main battle advantage—mobility. The soft clay near the river had been turned into a quagmire by the heavy rains, and the churning caused by horses’ hooves and chariot wheels made it worse. Within a very short time the chariots’ defense ground to a halt, literally bogged down in the mud. Those charioteers and cavalry not killed by the Macedonians took to their heels—or hooves—in a frantic attempt to escape. They left behind 400 dead, including Porus’s own son. It is said that virtually all the chariots—probably many disabled or deep in mud—were captured.

Porus Prepares For Battle

Porus was informed of the disaster, but took the evil tidings like a king, setting aside his personal feelings to deal with the crisis at hand. The rajah decided to give battle, but forewarned by his son’s fate he chose his ground carefully, selecting a broad sandy plain that would be suitable for cavalry.

Again, authorities differ on specifics, but Porus probably had 4,000 cavalry, 300 chariots, 200 elephants, and 30,000 infantry. The typical Indian infantryman was an archer, his principal weapon a heavy bamboo bow that shot an unusually long arrow. It must have taken strength to draw the bow, because Greek sources maintain Indian arrows could pierce corselets and shields with little difficulty. The Indian infantryman wore no armor; bare chested, he merely had a white cotton skirt girded around his loins. The Indians generally wore no helmets, either, but pulled their black hair into a topknot, bun, or small “ponytail.”

Porus’ Biggest Weapon? Gray “Battering Rams”

Porus placed his most formidable weapons, the war elephants, in his first line of battle. The elephant was something new to the Greeks and Macedonians, and certainly Alexander had never faced such a terrible threat. When properly used, elephants could be terrifying, great gray “battering rams” whose metal-tipped tusks could rend and gore and whose huge feet could trample and crush. The elephants were placed at 100-foot intervals with some infantry between the gaps to protect the elephant’s flanks. The bulk of the Indian infantry was behind the pachyderms and formed the second line of battle. Cavalry and chariots protected the army’s flanks.

Meanwhile, Alexander was advancing toward Porus’s assembling army. When the king and his Companions cavalry saw that the Indians were offering battle, he paused to let his own infantry come up and rest. Even though many were veterans who were inured to hardships, the march must have been a taxing one. Some may not have had body armor, but they did have helmets, swords, shields, and spears, and these tools of a soldier’s trade added extra weight.

They were marching in muddy ground, and it must have seemed to the Macedonian infantry that the very soil of India was on Porus’s side. Every time a soldier made a step, he sank deeply into the mud, and when he raised his foot, he would find it nearly trapped in the mud’s viscous embrace. Once the mud-spattered infantry arrived, they must have welcomed the rest Alexander allowed them. There was a practical reason why the king allowed them a “breather”; he didn’t want to have his winded troops engage a fresh enemy.

The Battle of Hydaspes was about to begin. The actual date of the battle is a matter of considerable dispute. The ancient writer Diodorus places it in “the archonship of Chiemes at Athens,” that is, about July. In one passage Arrian maintains it was in the Attic month of Munchion, or in about April/May. Yet later he contradicts himself by saying the battle was “after the summer solstice,” which would be after June 21. The “jury is still out” on the matter, but most sources say the date was May 326 b.c.

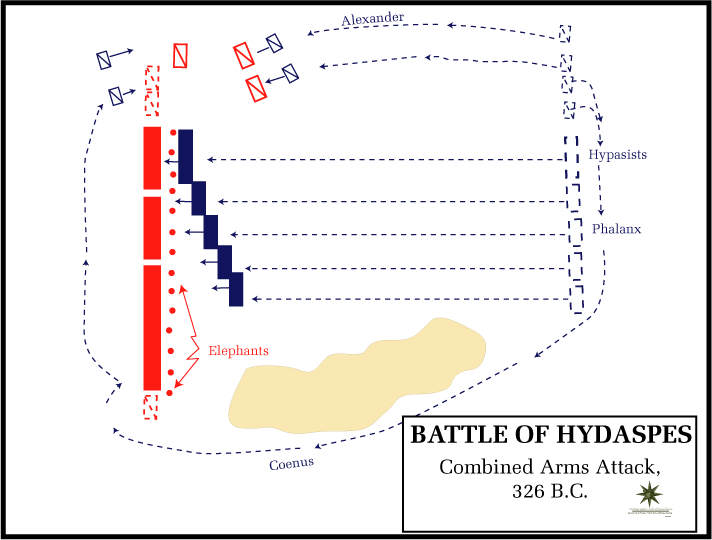

Exposing The Indian Horseman

Alexander opened the battle by sending a swarm of horse archers against the cavalry on the Indian left. It was a tactic he used earlier against the chariots, but now the stakes were much higher. Pelted by the arrow storm, the left-wing Indian cavalry moved against their swift-riding tormentors. This is exactly what Alexander hoped they’d do: Once exposed, the Indian horsemen would be easy prey for his Companions cavalry.

The king personally led his men forward, his Companions as usual in the van. The Macedonian cavalry smashed into the opposing horsemen like a juggernaut, the battlefield quickly dissolving into a bloody chaos of flailing hooves, clashing swords, and thrusting lances. Alexander was in the very midst of the melee, giving little thought to his personal safety as he traded blows with Indian horsemen.

Alexander Offers Himself As Bait

When Porus saw what was happening he ordered cavalry from his right wing to come to the aid of those on the hard-pressed left. The Indian right-wing cavalry moved in a kind of oblique fashion across the battlefield, riding in the “no man’s land” between the two armies. Apparently these right-wing “rescuers” were just about to fall on Alexander when Macedonian horsemen appeared in their rear as if by magic.

Alexander had been the bait, and now the Indian cavalry was well within the trap. In a prearranged maneuver orchestrated by Alexander, Coenus had taken at least one hipparchy and swung around to attack the Indian cavalry from the rear. Coenus had taken a wide, circuitous route; some speculate he had ridden behind the Macedonian infantry to conceal his movements and maintain the surprise. In any event, the Indian cavalry was thrown back in utter route, the survivors seeking refuge with the elephants.

Porus’ War Elephants Ready To Charge

Almost as if on cue the war elephants now took center stage, lumbering out to the attack. The Macedonian infantry accepted the challenge, but the situation was spine-chilling: A solid gray wall of powerful beasts, each weighing upward of two tons, rapidly closed the gap between them. As the elephants drew closer and the gap between the two sides grew narrower, the Macedonians were probably awed by these living fortresses of muscle, ivory, and bone. Trunks poised in a s-curve, the elephants trumpeted again and again, their cries heard distinctly over the din of battle. The celebrated Macedonian phalanx was about to receive an elephant charge; would it stand up to the test?

Along with the Companions cavalry, the Macedonian phalanx was a pillar of Alexander’s successes. The phalanx was a formation consisting of 16 files of men, each soldier armed with a two-handed pike of Balkan origin called a sarissa (plural sarissai) The sarissai were very long, about 15-18 feet from butt to spear point, and the use of such weapons required highly trained soldiers. Drill must have been constant.

Macedonian Phalanx Clash With Porus’ Elephants

The heart of the Macedonian phalanx formations were the Foot Companions, (pezhetairoi), formed into battalions usually named after their commanders. Like the cavalry some of the Foot Companions may have worn corselets/cuirasses, but it is certain all wore bronze helmets. The “Phrygian” style, which featured a bulbous crown that was likened to a cockscomb, seemed to be most popular. Most infantry helmets seem to have been painted blue, possibly an infantry color. Most soldiers had swords as secondary weapons and shields for protection. Since the sarissa was a two-handed weapon, some authorities have suggested that the shield was hung on a strap around a soldier’s neck to free his arms.

The leading ranks of the phalanx formations lowered their pikes, thus presenting a prickly forest of points to the onrushing elephants. Details are sketchy, but apparently the elephants smashed through the sarissai like so many matchsticks. The Macedonians were also throwing javelins—smaller, lighter spears—and both javelins and pikes began to find their marks. Unfortunately, wounds only enraged the elephants, goading them into a nearly uncontrollable fury. Ponderous heads slashed left and right, impaling Macedonian soldiers on their tusks, and probing trunks grasped struggling soldiers and flung them into the air like dolls. Other Macedonians were trampled underfoot, crushed into bloody pulp by rearing pachyderms.

Wounds Take Toll On Elephants

Yet other Macedonian soldiers brave or foolhardy enough to get close used swords and axes to chop and slash the elephants’ feet. Each elephant had a mahout or driver and one or two warriors on their backs. The warriors carried spears with bamboo hafts, and the mahout was also armed, but the real weapon was the elephant’s sheer brute strength. Behind their massive façade, however, the elephants had serious weaknesses. As noted earlier, they were very sensitive to wounds, and if wounded enough would go into paroxysms of fear and rage. Once in this state they were uncontrollable, dangerous to friend as well as foe. They also tended to go crazy in the heat of battle if their mahout was killed and they had no one to guide them.

According to some sources Alexander had given orders on how to deal with the elephants before the battle was joined. The king told his men to concentrate missile fire on the lead elephants, with special attention paid to the mahouts/drivers. Obeying his instructions to the letter, Macedonian pikes impaled mahouts from all sides, tumbling the drivers from their high perches straddling the elephants’ necks. Javelins also did their work, wounding elephants and killing or wounding their riders. Maddened with pain, rage, and fear, the elephants began floundering about, trampling and goring Indians as well as Macedonians. The battlefield was transformed into an amorphous mass of infantry, cavalry, elephants, and even chariots all jammed together in bloody confusion.

Phalanxes Destroy The Indian Cavalry

The initiative passed to Alexander; the battle was won. The king ordered his phlangites (men of the phalanxes) into the “locked shield” or sysnaspismos formation. With this order the phalanx formations closed up on a narrower front, thus presenting a near-solid line of men, shields, and pikes to the enemy. Once in sysnaspismos, the phalanxes moved inexorably forward. The Indian cavalry and chariots were in disarray, and the Indian infantry was no match for the phalanx. By this time, weakened by wounds and exhaustion, the elephants were a spent force, and many were captured by the Macedonians.

Porus’s army disintegrated, the survivors taking to their heels at first opportunity. Their retreat was suddenly cut off by Craterus, who had crossed the river from the base camp when he judged the Macedonians had been victorious. His timing was impeccable, and thousands of Indians were cut down in flight. Some did manage to make their escape, but Porus’s army was finished as a fighting force.

Porus Belatedly Surrenders

Rajah Porus himself did not flee. He had fought with his troops and been wounded, but refused to surrender. By some accounts he remained on his elephant, spear in hand, defying the Macedonians and rejecting all notions of flight or capitulation. His old enemy Taxiles was sent forward in an effort to get him to lay down his arms, but old grudges were hard to forget, and Porus nearly speared the rival rajah. Another Indian went forward, and he was more successful. Porus came down from his elephant and surrendered; although feeling faint from his wound he presented himself to Alexander.

Some sources claim Porus was five cubits high—that is, about seven and one-half feet tall! Others maintain that his height was measured by the shorter Attic cubit, which would reduce it to a more believable 6 feet or so. In any event, he must have towered over Alexander, who was said to be shorter than average.

“Treat Me Like A King”

“What do you wish I should do with you?” Alexander queried, and Porus’s answer was straight and to the point. “Treat me like a king,” said the proud rajah, an answer that was said to have pleased Alexander very much. The Macedonian not only spared Porus, but he made him a client king.

Casualty figures for the Battle of Hydaspes vary widely. Diodorus, who is as good a source as any, claims Porus lost 12,000 men and 9,000 captured. Others say 20,000 Indians were killed. Diodorus places Macedonian losses at 280 cavalry and 700 infantry. Whatever the figures, Hyspades was one of the bloodiest and hardest fought battles in Alexander’s career.

Soldiers Munity; Alexander Ends The Eastward March

Alexander wanted to push on to the Ganges River some 250 miles distant. He was sure that the Ganges emptied into Ocean, and thus marked the end of the terrestrial world. His war-weary soldiers did not share this enthusiasm for exploration. They had fought in many campaigns and endured many hardships in the quest for glory, and now they had had their fill. They had campaigned for almost eight years and marched some 17,000 miles. Now, the Macedonians wanted to enjoy their spoils and see their families if they had any. The soldiers mutinied, refusing to go any farther, and even an impassioned speech by Alexander failed to sway them.

Alexander finally acquiesced and started the long trek of return. He never again saw his homeland. Three years into the journey back he died in Babylon, aged only 32. His empire proved ephemeral, but he crafted a lasting achievement—the spreading of Greek culture. His conquests marked the beginning of the Hellenistic age that would last for centuries.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments