By John Wukovits

Rarely in the history of warfare had one nation absorbed such numbing losses in so rapid a time as did the United States in the Pacific War’s first five months. The surprise Japanese assault against Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, which dragged the United States into World War II, stunned American military and political leaders. In a few short hours Japanese dive-bombers had transformed America’s leading Pacific naval bastion into a blazing cauldron of death and had altered once-mighty battleships into twisted metal coffins. At the time, none would have likely believed that in just six months, the tide of war would turn at the Battle of Midway.

But in December, before the smoke had settled over Hawaii, Japanese forces struck at a series of American and British military installations, and like a destructive tidal wave swept away each with ease—Bataan, Corregidor, Wake Island, Guam, and Singapore fell one by one into the clutches of the victorious Japanese. Not one American triumph interrupted the string of defeats, causing civilians back home to wonder what had happened to the nation’s army and navy.

While elated over his forces’ victory at Pearl Harbor, the commander-in-chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, knew unfinished business lay ahead. His dive-bombers and torpedo planes had severely damaged the U.S. fleet, but they had missed one of their most important targets, the American aircraft carriers. As long as these floating airfields roamed the Pacific, Yamamoto could never count on possessing real superiority. To correct this, he hoped to draw out the remnants of the American fleet and destroy it in a gigantic sea clash, the “decisive encounter” for which Japanese strategists had long planned.

Yamamoto’s Plan For Superiority In the Pacific

If Yamamoto could succeed in this goal, the entire Pacific would lay open for his taking because there would be nothing left to stop him. He could take Hawaii at his leisure or even advance against California and the American West Coast. His main hope, however, was that another American defeat would cause his enemy to sign a truce that would give Japan a free hand in the western Pacific. Earlier in his career Yamamoto had visited the United States and seen her mighty industrial capabilities. He understood that if the war dragged on for more than six months to a year American factories would have the opportunity to pour out an unstoppable stream of ships, aircraft, and weapons that would spell eventual defeat for Japan.

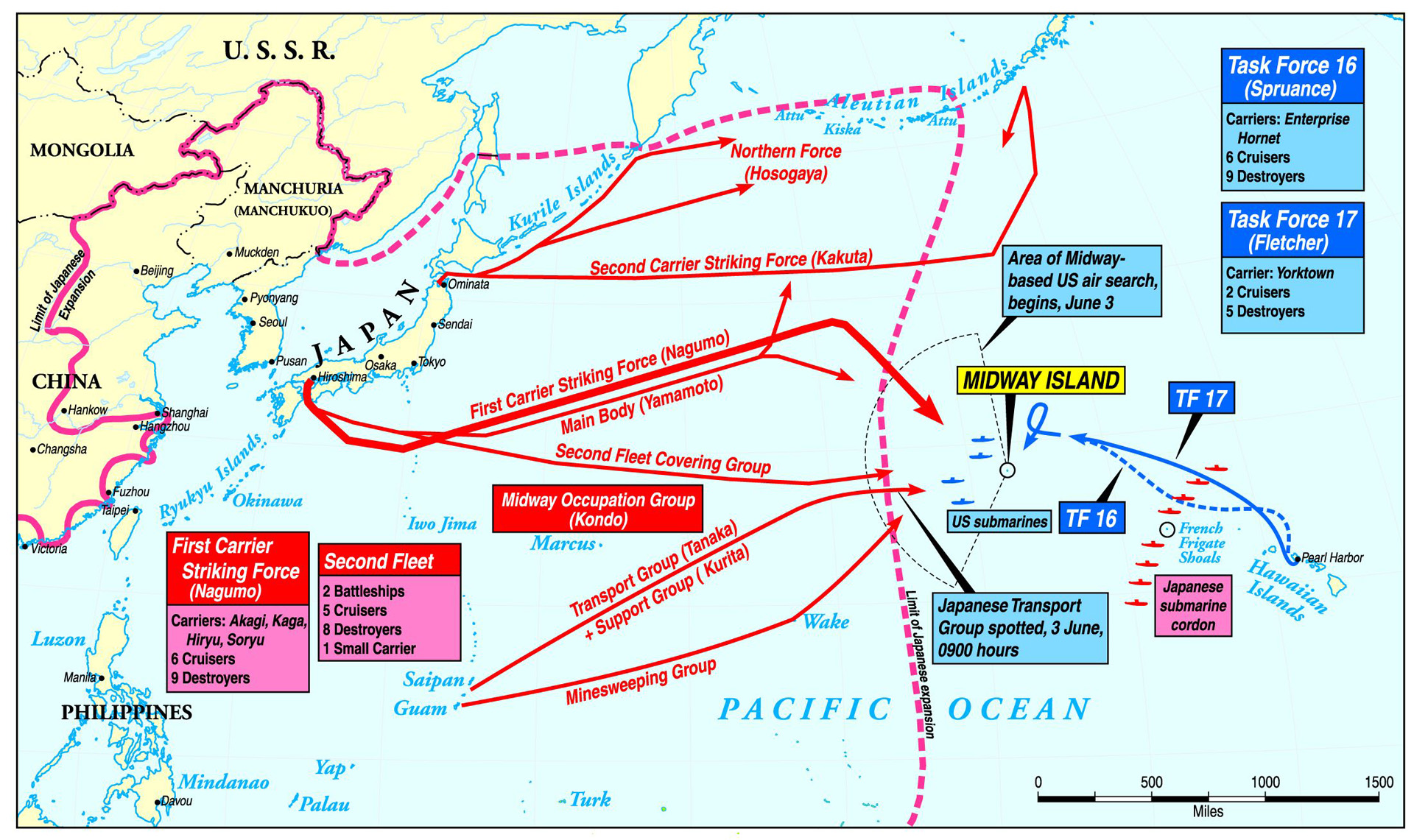

Yamamoto devised an operation to knock his adversary out of the war. He selected as his target the American base at Midway Island. Resting a little more than a thousand miles northwest of Hawaii, Midway served as the perfect bait to draw out the American carriers and whatever else remained of the U.S. Navy, for in Japanese hands the island would provide a base from which to launch an attack against Hawaii itself.

Another Surprise Attack in the Works at the Battle of Midway

Following an early June air strike on Midway by four Japanese aircraft carriers led by Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, an invasion convoy of 5,000 men protected by two battleships, six heavy cruisers, and numerous destroyers would seize Midway, which is actually an atoll consisting of two islets, Sand and Eastern. Lying 300 miles to the west with a potent battleship flotilla, Yamamoto would wait for the American Navy to steam out to protect Midway, then defeat it in a classic sea confrontation. Yamamoto based his plan on three assumptions: that the U.S. fleet would not steam out until after Midway had been attacked; that the Americans would have no more than two carriers available; and that the Japanese would achieve complete surprise.

The Japanese, who had already compiled an awesome string of victories, felt confident that the Midway operation would result in another. Their intelligence predicted that the Americans had lost the will to fight, and Japanese sailors boasted that they would “beat the enemy hands down.”

The Japanese expectations for victory proved premature. While Yamamoto possessed military superiority, the Americans had a weapon that nullified the Japanese advantage. Codebreakers had deciphered the Japanese naval code and were able to read as much as 90 percent of Yamamoto’s orders. By the end of May, Commander Joseph J. Rochefort and his team of cryptanalysts knew the date, intended target, and composition of Japanese forces deployed for the Battle of Midway’s operation.

This by no means guaranteed victory, for the United States Navy had been sorely weakened at Pearl Harbor. The codebreakers had provided the tremendous advantage of knowing approximately where Yamamoto’s forces would be, but the outnumbered Americans still had to battle a determined foe. In the final measure, victory or defeat would depend upon individual courage, instinct, and decision-making ability.

The Plan To Exploit a Brash American Admiral

The officer counted on to lead American naval forces, Admiral William F. Halsey, had commanded American aircraft carriers in their early forays against the Japanese, including the famous Doolittle bombing raid against Tokyo in April 1942. The brash Halsey was popular with his men and loved a good fight, but his impulsive nature sometimes caused him to react before a thorough analysis could be done. That tendency played directly into Yamamoto’s hands. He planned to goad the Americans into action with his Midway invasion flotilla, then pounce on the unsuspecting American ships with the powerful reserve forces he brought up from the rear.

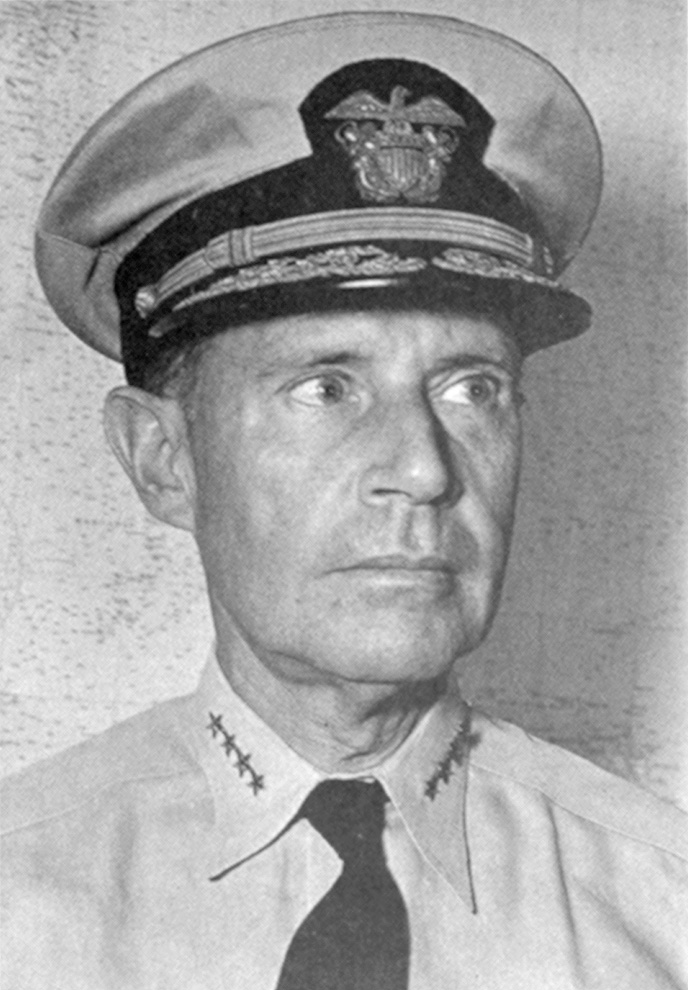

Halsey would play no role in the upcoming action, however. A severe skin rash forced the weary officer to bed. When he returned to Pearl Harbor from the South Pacific in late May 1942, exhausted from a lack of sleep and 20 pounds thinner, his superior, the Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Fleet, Admiral Chester A. Nimitz, took one look at the ragged officer and ordered him into the hospital. To command Halsey’s ships, Nimitz turned to Rear Adm. Raymond A. Spruance, Halsey’s cruiser commander. The substitution would have momentous consequences in the forthcoming battle.

“You Will Be Governed By the Principle Of Calculated Risk…”

Nimitz handed Spruance specific orders. He was to defeat the Japanese, but under no circumstances was he to lose the bulk of his ships, which at this early stage of the war were a precious commodity. Nimitz wrote Spruance, “You will be governed by the principle of calculated risk, which you shall interpret to mean the avoidance of exposure of your force without good prospect of inflicting, as a result of such exposure, greater damage to the enemy.” In other words, turn back the enemy, particularly by sinking his aircraft carriers, without letting the enemy sink too many of your ships, which were now the first line of defense for Hawaii and the West Coast.

Spruance intended to wait northeast of Midway. When his scout planes spotted the Japanese, hopefully before Yamamoto’s located the Americans, he would launch every available plane in an attempt to sink the Japanese carriers. To succeed, he had to play a game of cat and mouse with his adversary and hope that he could get his pilots into the air before his Japanese counterpart. If the Japanese found Spruance first, the U.S. Navy could suffer a disaster from which it might never recover.

Overmatched Spruance Pins Hope On Codebreakers

Spruance led his unit, called Task Force 16, to sea in late May. Consisting of the aircraft carriers Enterprise and Hornet steaming behind a screen of six cruisers and 12 destroyers, his force was numerically no match for the enemy. All Spruance could do was count on the edge handed him by American codebreakers and hope that he located the enemy first. Task Force 17, under Rear Adm. Frank Jack Fletcher, would join Spruance as soon as its sole carrier, the damaged Yorktown, could be hastily patched up in Hawaii. As the Battle of Midway unfolded, Fletcher was the senior American commander. However, Spruance commanded the stronger U.S. force and was obliged to fight the lion’s share of the battle on a tactical basis. Robert J. Casey, an American news reporter who accompanied Spruance, wrote the night before the battle that the admiral was heading out to meet the stronger Japanese “with a fly swatter and a prayer.”

Few observers believed the Yorktown, which had been seriously damaged during the Battle of the Coral Sea in May, could be repaired in time for the battle. When the ship entered dry dock, workers estimated they would require at least 90 days to adequately repair the carrier, but Admiral Nimitz said he needed the ship back in three days. Tirelessly working around the clock, 1,400 repairmen patched together the Yorktown sufficiently to get her back to sea by May 30. Although impaired, the Yorktown gave the Americans three aircraft carriers with which to halt the mighty Japanese fleet advancing toward Midway.

Yamamoto Counts Unhatched Chickens

Spruance faced an imposing challenge, for Yamamoto had assembled 11 battleships, 8 aircraft carriers, 22 cruisers, 65 destroyers, and 21 submarines for the operation. The Japanese admiral hoped to quickly destroy his adversary, then use his enormous reputation to convince government leaders to offer the United States some concessions to remove them from the war before her industrial might started churning out war materiel in quantities Japan could never match.

Unfortunately for the Japanese, a series of chance occurrences combined to influence the battle’s outcome even before the first shots were fired. Yamamoto learned from increased American radio activity that a strong enemy force might be in Hawaiian waters rather than still out of the way near Australia, but he chose not to alert Admiral Nagumo, who guided the advance force of four carriers, in order to maintain radio silence. Nagumo steamed toward Midway thinking he faced minimal opposition.

Unaware Nagumo Heads Towards Midway

Japanese submarines arrived at their observation posts surrounding the Hawaiian island of Oahu, but missed spotting the American fleet by one day. Planned aerial reconnaissance of Pearl Harbor had to be canceled when Japanese submarines discovered an American seaplane tender at French Frigate Shoals, from which they hoped to position their own observation planes. Consequently, having heard nothing to the contrary, Nagumo continued confidently toward Midway.

On the morning of June 3, Ensign Jack Reid piloted his scout plane from Midway on search patrol over the huge blue expanse of the Pacific. Suddenly, a string of ships appeared on the horizon. “Do you see what I see?” he asked his copilot. Reid had sighted the transports and destroyers of the Midway Invasion Force. Although a group of Army bombers from Midway attacked these ships, they inflicted little damage. Spruance was after bigger game, anyway. The Japanese carriers had to be somewhere in the area.

Pilots On Both Sides Rise Early and Enjoy Hearty a Breakfast

Anticipating that June 4 would bring together both sides in a life-or-death struggle, American and Japanese aviators awakened early in the morning to prepare for battle. U.S. Navy aviators enjoyed a hearty breakfast of steak and eggs, while their Japanese counterparts munched on rice, soybean soup, and chestnuts. At 4:30 am Nagumo launched 72 bombers and 36 fighters to attack Midway, while retaining 126 aircraft in case any American ships appeared. He ordered these planes to be loaded with armor-piercing bombs and torpedoes, the normal armament for use against steel-laden ships.

At the same time, Nagumo sent search planes aloft to look for any American naval vessels. Every search plane launched immediately except one from the cruiser Tone, which finally soared into the air 30 minutes late due to catapult problems. That slight delay would have major repercussions on the coming battle.

Japanese aircraft hit Midway but failed to knock out many vital targets. As the planes headed back to Nagumo’s carriers, the strike commander radioed that a second strike against Midway would be needed.

Japanese Carrier Group Sighted

Shortly after Nagumo dispatched his first air attack, Lieutenant Howard Ady emerged from a cloud bank in his Consolidated PBY Catalina search plane from Midway. He could hardly believe what he saw on the ocean below. Spread out before his astonished eyes were Nagumo’s aircraft carriers and supporting ships, which he said was “like watching a curtain rising on the Biggest Show on Earth.” He immediately relayed the information to Spruance aboard the Enterprise.

The controlled admiral calmly unrolled a large sheet of paper called a maneuvering board and plotted on it the range and bearing of the enemy aircraft. Spruance then used his thumb and index finger to estimate that the two forces stood 175 miles apart, barely inside the range of his torpedo planes. As other officers scampered from post to post in an effort to gain more information, Spruance looked up and quietly ordered, “Launch the attack.”

Although the distance would stretch the capabilities of his aircraft and would limit the time they could search for Nagumo’s carriers, Spruance decided the element of surprise far outweighed any risk. Besides, he hoped his planes would catch his adversary in the midst of recovering the Midway attack force.

Locked in a Deadly Race

With half his force airborne and circling, waiting for the rest to launch, Spruance learned that a Japanese scout plane had spotted the American carriers. Now in a deadly race to hit the enemy before he was hit, at 7:45 Spruance ordered the planes aloft to immediately head toward the Japanese without waiting for the rest of the American attack force. This decision meant that Spruance’s aircraft would not hit the enemy in a coordinated assault, but he hoped that striking first was more important than hitting in strength.

Steaming aboard the Yorktown 25 miles behind, Admiral Fletcher launched his dive- bombers and torpedo planes 30 minutes after Spruance. As a result, four different American forces flew at the Japanese, two from Spruance, one from Fletcher, and land-based aircraft from Midway. By 8:30, 157 American carrier aircraft sped toward the unsuspecting Nagumo, while not one Japanese plane headed toward the American carriers.

Nagumo faced an important decision. He had been told that a second strike against Midway was necessary, but the aircraft sitting on his decks were armed with bombs and torpedoes meant for use against ships. If he decided to send them against Midway Island, he would have to rearm the planes with the high-explosive bombs employed against land targets. This switch would require at least one hour and would leave him in a precarious position should American carrier aircraft appear. So far, none of his search planes had spotted enemy carriers.

Stunned By Unescorted American Bombers

While Nagumo pondered these thoughts, six American torpedo planes and four bombers from Midway attacked. As the planes descended, Japanese Commander Mitsuo Fuchida, who had earlier led the Japanese raid on Pearl Harbor, watched in fascination from the aircraft carrier Akagi. He noticed that, contrary to normal procedure, the American aircraft attacked without benefit of fighter protection, a suicidal maneuver in Fuchida’s opinion. He later wrote, “Still they kept coming in, flying low over the water. Black bursts of antiaircraft fire blossomed all around them, but none of the raiders went down. As Akagi’s guns commenced firing, three Zeros braved our own fire and dove on the Americans. In a moment’s time, three of the enemy were aflame and splashed into the water, raising three tall columns of smoke. The three remaining planes kept bravely on and finally released their torpedoes.”

One by one the heroic American pilots and their aircraft swooned into the sea or exploded in pieces. One plane crashed into Akagi’s deck without doing much damage, and only three aircraft returned from this initial encounter. Although the planes did little damage, Nagumo decided that he must hit Midway a second time to remove it as a threat to his carriers. The admiral ordered his waiting aircraft sent below to be rearmed.

A Difficult Decision

The switch was already under way when potentially disastrous news reached Nagumo. The tardy Tone scout plane radioed the presence of 10 enemy ships. According to Fuchida, the unexpected news hit Nagumo “like a bolt out of the blue.” The Midway attack planes were expected back within 10 minutes. Nagumo could order those planes, low on fuel, to circle the carriers while the rearming for a second strike against Midway was completed, but this would doom many to splash into the ocean. Or he could halt the rearming and land the aircraft from Midway, which would not only delay launching an attack against the American naval forces, but also place him in danger of being caught by enemy aircraft while landing his planes.

Nagumo sent a message to the Tone pilot asking if the 10 ships included any carriers. Before he received a response, three waves of American aircraft descended upon Nagumo’s ships. First, Major Lofton Henderson led 16 Marine Corps dive-bombers from Midway in an attack. Nagumo’s fighter cover and antiaircraft fire shot down eight of the 16, and the other eight departed without inflicting any damage to the Japanese.

American Bombs Scatter Japanese Carriers

Henderson’s dive-bombers had barely finished when 15 Army Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers from Midway, commanded by Lt. Col. Walter C. Sweeney, flew overhead at 8:10 am and released their load of bombs. Every missile smacked harmlessly into the ocean, but the attack forced Nagumo’s ships to swerve out of order to avoid being hit and caused more consternation for the already worried commander. Ten minutes later, 11 additional American aircraft under Major Benjamin Norris assaulted Nagumo’s fleet without doing any damage.

As Norris’s planes struck at the enemy, Nagumo received a response from the Tone scout plane stating, “Enemy force accompanied by what appears to be an aircraft carrier bringing up the rear.” The presence of an American carrier posed serious difficulties for Nagumo. When subordinates promised Nagumo that the entire Midway strike force could be recovered in 30 minutes, Nagumo gambled on landing the planes returning from Midway, then rearming every aircraft for a strike against the enemy ships. All he had to do was get through the next half hour, and he thought victory would be his.

By this decision, Nagumo doomed his force to destruction,” wrote prominent World War II historian Ronald H. Spector, for Nagumo lost his race against time. Unlike Spruance, who immediately launched his aircraft, Nagumo hesitated and invited defeat.

America’s Fate in the Hands of 240 Pilots

“If I do not come back—well, you and the little girls can know that this squadron struck for the highest objective in naval warfare—To Sink the Enemy.’” So wrote Commander John C. Waldron to his wife mere hours before climbing into his torpedo plane to lead the Hornet’s Torpedo Squadron Eight into battle with the Japanese. He had no idea what fate awaited him, but understood that he and his men had to do whatever they could to stop the enemy’s advance.

Aboard Yorktown, Lieutenant Dick Crowell voiced the message in even simpler terms when he bluntly told that carrier’s aviators, “The fate of the United States now rests in the hands of two hundred and forty pilots.”

Newspaper reporter Robert J. Casey, accompanying the American carriers to write an account for the people back home, asked one officer for his opinion of the aviators who piloted the old, slow-moving torpedo planes. “They don’t stand any watches,” he replied. “They don’t have to go out and do patrol jobs. They don’t have any dogfights to worry about. They may sit around playing poker for a month before they have to go out…. Then they go out and they don’t come back.”

America’s Kamikazes

These men, and others who braved enemy antiaircraft fire and fighters to swoop down on Nagumo’s carriers, altered the fortunes of war. Few returned, but the legacy they left behind remains to this day, for without their valor and sacrifice the Pacific War would have taken an ominous turn for the United States.

Eager to strike first, Spruance had again abandoned hopes of a coordinated assault. Instead, similar to the earlier American strikes, aircraft from the three American carriers arrived over Nagumo’s force at varying times and different altitudes. Rather than one powerful thrust, the pilots descended in a series of individual charges.

Waldron had instructed the men in his unit’s 15 obsolescent Douglas TBD Devastator torpedo planes, “If there is only one plane left to make a final run in, I want that man to go in and get a hit.” When he spotted three of the enemy carriers, he wiggled his wings as the sign to descend closer to the water so they could deliver their torpedoes.

The Heroism Of Torpedo Squadron Eight

Thirty Japanese fighters immediately challenged Torpedo Squadron Eight as the cumbersome torpedo planes started their slow approach from eight miles distant. Enemy aircraft zipped by on all sides, with angry guns spitting bullets toward the Americans, while thick antiaircraft fire churned the ocean surface.

“He went straight for the Japanese fleet as if he had a string tied to them,” recalled Torpedo Squadron Eight pilot Ensign George Gay. Below, Fuchida watched from Akagi as the 15 American aircraft bravely attacked. “Their distant wings flashed in the sun,” he later wrote. “Occasionally one of the specks burst into a spark of flame and trailed black smoke as it fell into the water.”

With Commander Waldron in the vanguard, the 15 planes droned toward their target. From his cockpit, Ensign Gay saw enemy shells rip into Waldron’s left gas tank and ignite the fuel. Moments before the commander’s aircraft spun into the ocean, Gay noticed Waldron and his radioman madly trying to free themselves from the blazing plane.

The Survivors Continued To Fight On

Other American aircraft quickly disintegrated under a hail of Japanese fire or plummeted into the ocean, but the survivors continued on. Soon, Gay piloted the only torpedo plane remaining. He ignored the bullets, shells, and Japanese fighters in hopes of delivering a torpedo.

They got me,” cried his radioman, Bob Huntington. When Gay turned around to check on his companion, a sharp stab burned his left arm. Although wounded, he held the plane steady long enough to launch his torpedo from what seemed yards from a carrier, jerked the craft upward with all his might, cleared the enemy ship by 10 feet, and sped away on the other side. Unfortunately, four Japanese fighters jumped on his tail and peppered his aircraft with fire. Gay spun into the sea a quarter-mile from the carrier.

Bleeding from his wounds but alive, Gay managed to free himself from the cockpit and float away from the sinking airplane. He grabbed a seat cushion that floated nearby to use as a shield. Gay, the lone survivor of Torpedo Squadron Eight, had landed right in the middle of the enemy fleet.

Throwing Japanese Carriers Into Dissary

Although Gay’s unit failed to hit the Japanese carriers, they threw the enemy ships into disarray and drew the enemy fighters down near sea level. No sooner had Waldron’s squadron ended its charge when 14 Enterprise Devastators led by Commander Eugene E. Lindsey attacked. Japanese fire destroyed 10 of the 14 American aircraft, and again no hits were recorded on the carriers, but as with Waldron’s, the assault confounded the Japanese and all but halted the rearming process ordered by Nagumo. Torpedoes, bombs, and fuel hoses dangerously littered the flight decks of each carrier.

In a third successive charge, Commander Lance E. Massey arrived with 12 Yorktown Devastators and fighter protection as Lindsey delivered his attack. Fighter pilot Commander James Thach recalled, “The air was just like a beehive…” as Japanese and American aircraft sped toward each other, and he quickly realized how outnumbered he and his men were. “I was utterly convinced then that there weren’t any of us coming back because there were still so many Zeros.”

American Dive Bombers To the Rescue

His fears seemed to materialize as 10 of the 12 Yorktown torpedo planes tumbled into the ocean without scoring any hits. Wherever he turned, Thach spotted more enemy fighters, but the determined aviator thought, “We’re going to take a lot of them with us if they’re going to get us all.” At that moment a glittering image from above distracted Thach, and he looked up to see “this glint in the sun and it just looked like a beautiful silver waterfall; these dive bombers coming down.”

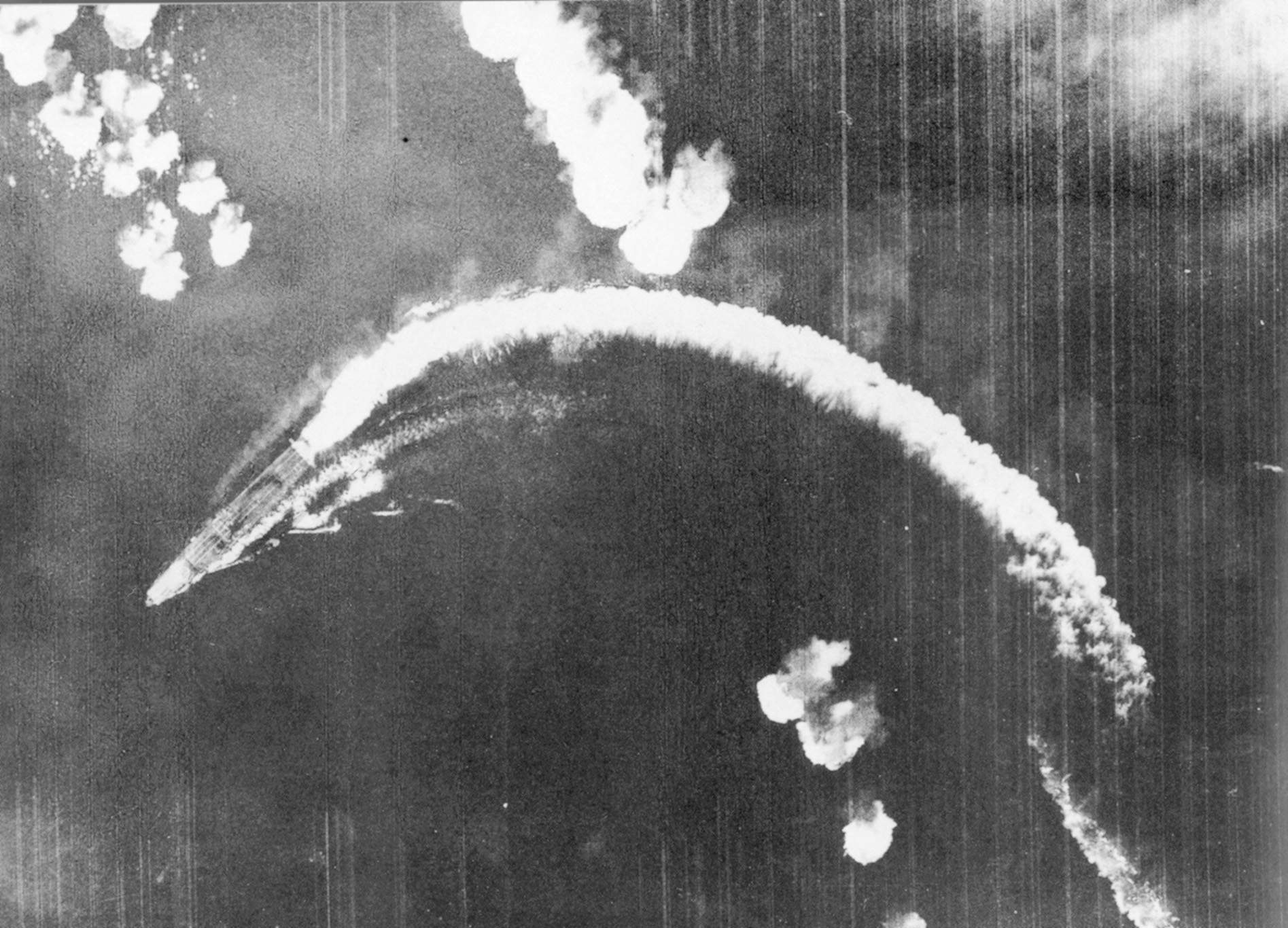

Nagumo’s worst fear had suddenly materialized. He had been caught by American dive- bombers with his flight decks jammed with aircraft, fuel hoses, and stacked ordnance. He could do nothing but hope his antiaircraft fire brought down the enemy planes before they hit his carriers.

Thirty-seven Douglas SBD Dauntless dive- bombers from Enterprise, led by Lt. Cmdr. Wade McClusky, and 17 Yorktown Dauntlesses, commanded by Lt. Cmdr. Maxwell F. Leslie, simultaneously arrived over the Japanese Fleet and attacked at right angles to each other. Since the torpedo planes had drawn the Japanese fighters to wavetop level, the dive-bombers could attack from on high without worrying about being intercepted. A series of fortunate events and the sheer courage of the torpedo plane pilots had resulted in a brief window of opportunity for the attackers.

Fuchida Watches In Horror

McClusky directed his men toward the carriers Akagi and Kaga. One by one, the 37 aircraft screamed down at their targets. Two bombs ripped into the Akagi’s flight deck and detonated Japanese bombs and torpedoes stacked on it. Within seconds the carrier was engulfed by flames. Other Enterprise dive- bombers planted four bombs on Kaga, including one that demolished the island superstructure and killed most of the officers on the bridge. Scorching fires quickly spread throughout the carrier and trapped numerous members of the crew in a fiery death.

Fuchida watched in horror as the Americans pounded the carriers. “The terrifying scream of the dive bombers reached me first, followed by the crashing of a direct hit. There was a blinding flash and then a second explosion much louder than the first.” Fuchida expected more to occur, but in an instant the attack ended. The noise was “followed by a startling quiet as the barking guns suddenly ceased. I got up and looked at the sky. The enemy planes were already gone from sight.”

As Fuchida gazed at the twisted flight deck, mangled bodies, and burning aircraft, tears coursed down his face. The officer later said he “was horrified at the destruction that had been wrought in a matter of seconds.” Reluctantly, Nagumo transferred to another ship while Akagi’s captain lashed himself to a bulkhead to go down with his carrier.

Carriers Methodically Destroyed

While McClusky’s aviators swarmed about the Akagi and Kaga, Leslie selected a third carrier, the Soryu, as his target and guided his 17 dive-bombers toward the quarry. Though he claimed that bombing a ship from the air was “like trying to drop a marble from eye-level on a scared mouse,” Leslie and his men quickly planted three bombs onto the carrier’s flight deck. In an instant, explosions and flames swallowed the Soryu’s surface, and within 20 minutes the crew started to abandon the sinking ship.

The fourth Japanese aircraft carrier, Hiryu, had been obscured by cloud cover and was undetected during the attacks. In retaliation, a small force of aircraft was scraped together aboard Hiryu and launched against the Yorktown. The Japanese aircraft located the Yorktown and wounded her with three bomb and two torpedo hits, but American planes found Hiryu three hours later. Twenty-four Enterprise dive-bombers so damaged the Hiryu that she sank the following day.

Yorktown Meets Her End at the Hands of a Japanese Sub

Despite her serious damage, it appeared that the Yorktown might survive yet again. However, on the morning of June 6, the crippled carrier was spotted by the Japanese submarine I-168 and sent to the bottom by two torpedoes. The destroyer Hammann was sunk in the same attack.

A total of 147 American planes were lost during the Battle of Midway, along with 307 sailors and airmen. Aside from their four aircraft carriers, the Japanese also lost the heavy cruiser Mikuma, while her sister, Mogami, was severely damaged. Perhaps most devasting of all for the Japanese was the loss of 332 aircraft and many experienced pilots who were irreplaceable. A total of 2,300 Japanese sailors and airmen were killed.

The Battle of Midway’s Six Short Minutes That Changed Course Of the South Pacific

In six minutes, McClusky’s and Leslie’s dive-bombers had changed the course of the Pacific War. Three carriers had been sunk, and a fourth soon followed them to a watery grave. The United States had wrested the initiative from Japan. From now on, the Japanese would be forced to fight defensively in the Pacific.

Although he had suffered huge losses, Admiral Yamamoto still hoped to extract victory from the ashes by luring Spruance’s naval forces into a night battle against his powerful battleships. However, the cautious Spruance would not permit his ships to be caught in a night surface action against a superior enemy force. The Japanese were also supremely proficient at night fighting.

Yamamoto Assumes Responsibility for Devastating Defeat

When Yamamoto realized that Spruance was not chasing him, he concluded that the Battle of Midway was over and canceled the rest of the operation. When a subordinate wondered who would apologize to the Japanese emperor for the defeat, Yamamoto answered, “Leave that to me. I am the only one who must apologize to His Majesty.” He then retired to his cabin and refused to see anyone for three days.

The victory enabled Admiral Nimitz to issue a statement that “Pearl Harbor has now been partially avenged.”

Reporter Casey wrote that if the Japanese had won at Midway, “We might well have been moving our bases to a more suitable place—such as the bottom of the Grand Canyon.”

Japanese Captain Yasumi Toyama, who served in the battle, declared, “After Midway we were defensive, trying to hold what we had instead of expanding.”

A Decisive Battle for the History Books

Three years after World War II ended in 1945, experts at the Naval War College completed an analysis of the Battle of Midway. They praised Spruance’s calm, decisive leadership and concluded that the crucial victory transformed the Pacific War.

The analysis of the battle reads in part, “By destroying four of Japan’s finest aircraft carriers together with many of her best pilots it deprived the Japanese Navy of a large and vital portion of her powerful carrier striking force; it had a stimulating effect on the morale of the American fighting forces; it stopped the Japanese expansion to the east; it put an end to Japanese offensive action which had been all conquering for the first six months of war; it restored the balance of naval power in the Pacific which thereafter steadily shifted to favor the American side; and it removed the threat to Hawaii and to the west coast of the United States.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments