By Jon Diamond

Following the 76th anniversary of the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) from the beaches and harbor of Dunkirk, one is amazed at the number of articles and volumes written about the subject. These encompass official histories, personal accounts of the battle’s participants, and historical tomes. Those nine days of Sunday, May 26, 1940, through Monday, June 3, 1940, live on in the very words of the military and political leaders who, for posterity’s sake, kept meticulous diaries and memoirs, often against existing regulations.

One of the unforgiving aspects of history is that as time marches on the actual words and observations of principal participants in historic events (through their diaries and memoirs) gradually become blurred by review, synopsis, and tangential reference. The tincture of time distorts the views that were held from the outset of an event’s occurrence. Also, the beholder of the moment does not have the luxury of hindsight nor the ability to peruse other documents and sources to form an opinion. The notation made at the moment is often spontaneous and candid.

It was primarily due to the mettle of Lord Gort, Vice Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay, and Captain William Tennant that difficult and timely decisions were made that ultimately allowed the Dunkirk evacuation to commence, continue, and succeed.

No Confidence in Lord Gort

On June 2, 1940, British War Minister Anthony Eden summed up the BEF’s experience during the previous three weeks in northern France and Belgium quite adequately: “The BEF advanced into Belgium and took up its position on the River Dyle. The advance lasted several days. Through events it could not control our Army had to come back in less than half that time. It did so with little confusion and with few losses. Seventy-five miles forward, a fight at the end of the advance, and seventy-five miles back, fighting all the way, all in the space of ten days.”

On May 14, the BBC broadcast an announcement requesting all owners of “self-propelled pleasure craft” between 30 and 100 feet long to send them to the Admiralty to augment the latter’s fleet of ships suitable for a coastal evacuation. Across the English Channel in France, the commander of the BEF was John Standish Surtees Prendergast Vereker, 6th Viscount Gort, who at the time of Dunkirk was 54 years old. He was a member of the Grenadier Guards and the recipient of the Military Cross, the Distinguished Service Order and two Bars, and the Victoria Cross in addition to being wounded four times during World War I.

Despite these impeccable credentials, up to the moment when he was selected by the then War Minister Leslie Hore-Belisha to be the chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), Gort had never commanded any unit larger than a brigade. One observer noted of Gort, “I had no confidence in his leadership when it came to handling a large force. He seemed incapable of seeing the wood for trees.”

As historian Alistair Horne has pointed out, Gort, during the Phony War, had “busied himself tirelessly with such details as the proper use of hand-grenades, the art of patrolling at night, small-arms fire, and map-reading in the snow. He should have perhaps been voicing to the British Cabinet his doubt of the French Army and its strategy.” Thus, Gort, according to General Sir Edward Spears, the British liaison to the French high command, was regarded “as a sort of friendly and jovial battalion commander” by the French generals, and they treated him as such.

Withdrawal to Dunkirk

On May 16, Lt. Gen. Sir Henry Pownall, Gort’s chief of staff, entered in his diary, “The news from the far south is very bad. German mechanized columns are getting deep into France towards Laon and St. Quentin. I hope to God the French have some means of stopping them and closing the gap or we are bust.”

Already Pownall was visualizing a wedge driving between the British and French forces in the south with its spearhead advancing due west to the Channel coast. The next day’s entry revealed, “The Germans can drive on west to Amiens-Abbevile or northwest to Calais, unless somehow they can be stopped.” Also, on the 17th, Pownall commented, “Gort is quite splendid, not at all rattled, rather enjoying himself with a fine grasp of the operation as a whole. He knows more about war than all these Frenchmen.”

This day, Gort ordered the British I and II Corps to withdraw from the River Senne to the River Dendre. According to Pownall, “If Gort had decided to stay on the Senne we should tonight have an open flank of some twenty miles!” According to a French historian, “The night of May 18-19th marked the crucial moment when the British High Command started thinking in terms of a separate strategy that might mean breaking with its French and Belgian allies.”

On May 19, Churchill spoke to the British people. “It would be foolish to deny the gravity of the hour,” he intoned. “It would be still more foolish to lose heart or courage, or to suppose that well-trained and well-equipped armies numbering millions of men can be overcome in the space of a few weeks or even months by a swoop or raid of mechanized vehicles, however formidable.”

In a rather contradictory fashion, Pownall called Maj. Gen. R.H. Dewing at the War Office in London, and as a result of that conversation a precautionary measure was instituted to assemble a small fleet to assist in an evacuation of the BEF from northern France and Belgium via Dunkirk if needed. Pownall wrote, “We were therefore examining the possibility of a withdrawal in the direction of Dunkirk whence it might be possible to get some shipping to get some troops home.”

Earlier on the 19th, both Pownall and Gort realized that by “going north-west one could get the flank protection of the Douai-La Bassee-Aire Canal…. A series of water obstacles on this avenue of retreat gave some hope of conducting it in a more or less orderly fashion. But the withdrawal ended at the sea at Dunkirk, from which hopes of evacuation of personnel were small indeed (and of material none at all) in the light of modern air bombing against a port.”

Defeatism in the British Camp

By May 20, Gort began to challenge the wisdom and orders of London and the French high command, in effect making him both defiant and disobedient, which ultimately was fortunate for the BEF and Britain. An apt comparison is drawn by Horne between Admiral John Jellicoe during the World War I naval battle of Jutland and Gort in France: “Gort, by 20 May was certainly the man who, by forfeiting Britain’s only land force, could easily have lost the war at least in a week of afternoons.”

On May 20, Churchill sent over the current chief of the Imperial General Staff, Field Marshal Lord Ironside, to assess how well-founded Gort’s pessimism was and secondly to quash his notion of evacuation. Churchill stated that Ironside “could not accept this proposal [Gort’s retreat to the coast], as, like most of us, he [the CIGS] favors the southward march.” Ironside was to tell Gort to “force his way through all opposition in order to join up with the French in the south.”

However, Ironside found the situation was just as bad as Gort had indicated. He found the local French generals “in a state of complete depression. No plan, no thought of a plan. Ready to be slaughtered. Defeated at the end without casualties…. Situation desperate…. Personally, I think we cannot extricate the BEF.”

Despite these pessimistic views, Gort told Ironside that he was still inclined to launch a counterattack south of Arras with two divisions, the 5th and 50th. A few days later, Ironside’s diary entry showed his own continued sense of defeatism. “The final debacle cannot be long delayed and it is difficult to see how we can help. It cannot mean the evacuation of more than a minute portion of the BEF and the abandonment of all the equipment of which we are so short in this country. Horrible days we have to live through…. We shall have lost practically all our trained soldiers by the next few days unless a miracle appears to help us.” Ironside thought that 30,000 men at the most might get away.

The decisive action of May 20, 1940, went to the German armored columns of General Heinz Guderian, the foremost proponent of the concept of blitzkrieg, or lightning war. By 2 pm, Guderian was at the outskirts of Abbeville. The gap between the French armies in the north and those in action along the Somme was 55 miles by late afternoon. The Allied armies were well cut in two. Allied forces fighting in Belgium and Flanders were caught in a trap.

Counterattack in Arras

On May 21, Gort ignored a French delay in the Arras attack and ordered the British 5th and 50th Divisions with 100 tanks forward. German General Erwin Rommel, commanding the 7th Panzer Division, noted, “Powerful armored forces had swarmed out of Arras, subjecting us to heavy losses in men and equipment. The anti-tank guns that we speedily brought into action proved too light to be effective against the heavily armored British tanks. Most of them were put out of action by the enemy artillery fire— likewise their crews…. Finally the divisional artillery and some 88mm antiaircraft guns managed to halt the enemy armor.”

This operation was to be the only serious counterattack launched by the encircled Allied armies. The results convinced Gort that the only way out for the BEF was to withdraw to Dunkirk, thereby ignoring any further attempt to break through to the French forces in the south. The Arras attack shocked the German high command.

According to Pownall, “General Rommel was so shaken that he thought he was being opposed by five divisions.” Some historians have asserted that Gort’s decision to attack at Arras may have started a chain of decisions to save the BEF that would culminate in this being his “moment of destiny.

On May 22, the Royal Air Force evacuated the airfield at Merville, its final base in France. All future operations, including Dunkirk, would be conducted from Britain.

On May 23, Rommel outflanked the remnants of the British 5th and 50th Divisions from the west. This maneuver truly upset Gort. He had lost almost all confidence in the orders coming from the French high command. Gort decided to withdraw his forces north of Arras during the night. Pownall opined in his diary entry on May 23, “For one thing we haven’t ammunition to conduct real offensive operations, perhaps 300 r.p.g. [rounds per gun] on the average, is all we have at and in front of railhead. We are none too well off for small arms ammunition—and have asked for some to be dropped by air. Our rations are only about three days. That is mighty close running in view of the bombing that has taken place, and will continue, on our ports.”

In fact, Gort warned Eden, “My view is that any advance by us will be in the nature of a sortie and relief must come from the south as we have not, repeat not, ammunition for serious attack.”

4,368 Evacuated From Boulogne

Eden’s response reassured Gort along the lines of his mental preparation. “Should, however, situation on your communications make this at any time impossible you should inform us so that we can inform French and make naval and air arrangements to assist you should you have to withdraw on the northern coast.”

General Sir Alan Brooke’s entry for this date was no more optimistic. “Nothing but a miracle can save the BEF now and the end cannot be very far off!… It is a fortnight since the German advance started and the success they have achieved is nothing short of phenomenal. There is no doubt that they are most wonderful soldiers.”

According to Horne, “Gort’s judgment was now already formulated. It was that the Weygand Plan would never materialize, that the French would never attack, and that the only hope of preserving anything of the BEF was to fall back on Dunkirk while there was still time.”

Gort’s order for the 5th and 50th Divisions to disengage on the night of May 23 to begin the withdrawal from Arras demonstrated that he knew his actions would culminate in evacuation. Gort was aware that by then the French Army was finished and that it was his duty to save that force for future actions.

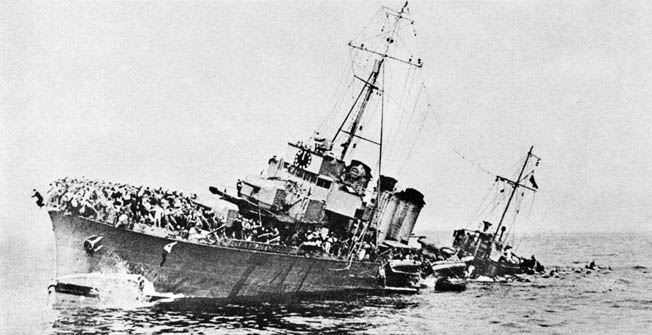

During the night of May 23, the evacuation of Boulogne began. By 3 am on the 24th, the destroyer HMS Vimeria left the mole in Boulogne harbor. According to the official war diary of the evacuation, the last vessel “reached Dover at 0355/24 where she landed some 1,400 men. This took the total number of men, women and children evacuated from Boulogne to roughly 4,368.” After this ship’s departure, all organized resistance in Boulogne ceased.

With the German capture of Boulogne, Vice Admiral Ramsay, who was in charge of Operation Dynamo, had just lost a major port of embarkation. Ramsay was born in London in 1883 and joined the Royal Navy in 1898. During World War I, he served for two years on a monitor as part of the Dover Patrol off the Belgian coast. He resigned from the Navy in 1938 but was coaxed out of retirement by Churchill the following year. For Operation Dynamo, Ramsay took up station in the underground tunnels beneath Dover Castle.

Why Did Hitler Hold Back His Panzers?

On May 24, Hitler issued a phenomenal order to corps commanders to halt the panzer spearhead. The task of ending the Battle of France would be left to the Luftwaffe and the infantry. Upon issuing this order, Hitler began to speak admiringly of the British Empire, the usefulness of its existence, and the value of the civilization that Great Britain had introduced to the world. His aim was to make peace with Britain on a basis that the British would regard as honorable.

German General Ewald von Kleist noted, “The German armor was nearer the port [of Dunkirk] than the bulk of the British forces.” General Ritter von Thoma, who later was to surrender to British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery in North Africa, remembered, “I was right out in front, with the first tanks, near Bergues…. from there I could see everything that was going on in Dunkirk.”

Kleist questioned Hitler a few days later about his decision, pointing out that the Wehrmacht had wasted a unique opportunity by not occupying Dunkirk before the British escaped. “Possibly,” replied Hitler, “but I didn’t want our tanks to get stuck in the Flanders mud.”

Kleist also claimed, “[Luftwaffe chief Hermann] Göring had undertaken to settle Dunkirk’s hash with planes alone…. He begged Hitler to bestow the honor not on the army but on the Luftwaffe, thereby making the battle of Dunkirk a victory for the regime.”

Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt claimed, “The Führer had counted on a speedy end to western operations…. He deliberately let the bulk of the BEF escape, so as to make peace negotiations easier.”

Hitler, by halting his tanks and overestimating Göring’s abilities, had made the first serious mistake since the start of hostilities. His order enabled the Allies to embark units from the Dunkirk trap. During the three-day respite afforded by the halting of the panzers, Gort had managed to erect a strong defensive perimeter around Dunkirk.

“Evacuation Will Not (Repeat Not) Take Place”

Pownall’s wrote on May 24, “We are examining again the withdrawal northwards to the coast from Calais to Ostend.” Even he realized that something was afoot in the German assault when he noted later that night, “There is certainly one [German panzer formation] now round Calais and as far east as Gravelines where they seem to have been stopped.”

Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax wrote in his diary on May 25, “The one firm rock on which everyone was willing to build for the last two years was the French Army, and the Germans walked through it like they did the Poles.”

General Sir John Dill, commander of the BEF’s I Corps, visited Gort’s headquarters on the 24th. According to Pownall, “He hinted too that there was criticism at home that the BEF, 200,000 fighting men who claimed to be better fighters than the Bosche, were not doing enough.”

That same day, Churchill decided that the garrison at Calais, commanded by Brigadier Claude Nicolson, must hold out for as long as possible to allow the BEF to continue to retreat into the Dunkirk perimeter. Ships originally sent to Calais to evacuate Nicolson’s force were ordered back to Dover. Churchill contacted Nicolson: “Every hour you continue to exist is of the greatest help to the BEF. Government has therefore decided you must continue to fight. Have greatest possible admiration for your splendid stand. Evacuation will not (repeat not) take place.”

Pownall’s entry for May 25 summed up the events quite well. “It is all a first-class mess-up and events go slowly from bad to worse, like a Greek tragedy the end seems inevitably to come closer and closer with each succeeding day and event.”

Lord Gort’s Dilemma

Also on May 25, Lord Gort was somewhere near Lille contemplating a major dilemma. The Germans had captured Boulogne, and Calais would surrender the next day. If Belgium capitulated, a 20-mile gap would develop on his left flank. In a moment of prescience, Gort ordered General Pownall to move the 5th and 50th Divisions from the south and “send them over to Brookie [General Alan Brooke] on the left” to fill the gap between the BEF left flank and the fast disintegrating Belgian Army.

This move violated Gort’s orders from both London and the French General Staff, but it saved the BEF from destruction. However, Dill, slated to replace Ironside as chief of the Imperial General Staff on May 27, telegraphed Churchill outlining the dangers now threatening the BEF as a result of the breaching of the Belgian front.

In reply to messages from Dill and Gort, Eden wired Gort, “I have had information all of which goes to show that French offensive from Somme cannot be made in sufficient strength…. Should this prove to be the case you will be faced with a situation in which the safety of the BEF will predominate.”

Churchill telegraphed Reynaud at 6:55 pm, “I must tell you that a Staff Officer [probably Pownall] has reported to the War Office confirming the withdrawal of the two divisions from the Arras region.” Thus, Gort’s decision to withdraw to Dunkirk, although unknown to the French, was not made in vacuo of the British leadership. However, since Gort’s decision was made without consulting the French, it embittered them immensely.

On the morning of May 26, Nicolson’s defenders held out for several hours. During the afternoon, the Germans captured vital defensive points in Calais. Nicolson surrendered at 4 pm. This leader of a forlorn last stand would die of his wounds as a prisoner of the Germans at Rotenberg am Fulda, a castle south of Frankfurt, in June 1943. Guderian was now poised to capture Dunkirk when he received a further order (in addition to order of May 24) to halt, thereby forbidding his forces to cross the Aa Canal.

Lord Gort received a message from Eden in the morning confirming that his chief concern was the BEF’s safety. Eden stated, “Only course open to you may be to fight your way back to west where all beaches and ports east of Gravelines [between Calais to the west and Dunkirk to the east] will be used for embarkation. Navy will provide fleet of ships and small boats and RAF would give full support…. Preliminary plans should be urgently prepared.”

Gort replied, “I must not conceal from you that a great part of the BEF and its equipment will inevitably be lost even in best circumstances.”

French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud had visited London, and upon his departure the war office telegraphed Gort, “Prime Minister has had conversation with M. Reynaud this afternoon…. It will not be possible for French to deliver attack in the south in sufficient strength to enable them to effect junction with northern armies. In these circumstances no course open to you but to fall back upon the coast…. M. Reynaud communicating General Weygand and latter will no doubt issue orders in this sense forthwith…. You are now authorized to operate towards coast forthwith in conjunction with French and Belgian Armies.”

Thus, Gort’s plan to retire to Dunkirk was officially backed in London; however, it left the BEF commander with the impression that Reynaud and Weygand also concurred, which was not the case, and would stir the political pot.

The Dunkirk Evacuation Begins

At 6:45 pm, the Admiralty issued the order to begin the evacuation of troops from Dunkirk. Lt. Col. John Austin’s personal account describes the BEF’s retreat to Dunkirk. “Every road scouring the landscape was one thick mass of transport and troops, great long lines of them stretching far back to the Eastern horizon, and all the lines converging towards the one focus, Dunkirk. Ambulances, lorries, trucks, Bren gun carriers, artillery columns, everything except tanks, all crawling along these roads in well-defined lines over the flat, featureless country.”

Göring had been warned about the possibility of a British evacuation on May 27. German Admiral Otto Schniewind told him, “A regular and orderly transport of large numbers of troops with equipment cannot take place in the hurried and difficult conditions prevailing…. Evacuation of troops without equipment, however, is conceivable by means of large numbers of smaller vessels, coastal and ferry steamers, fishing trawlers, drifters, and other small craft, in good weather, even from the open coast.”

German reconnaissance aircraft reported that there were 13 warships and nine troop transports in Dunkirk harbor. German Army Intelligence concluded, “The embarkation of the BEF has begun.”

Captain William Tennant, chief staff officer to the First Sea Lord who had also just been appointed captain of the battlecruiser HMS Repulse, had volunteered his service to Vice Admiral Ramsay to help with the evacuation at Dunkirk. Ramsay ordered him to Dunkirk as senior naval officer (SNO) ashore, and early on the afternoon of May 27 he sailed from Dover with 12 officers and 160 ratings with a communications staff aboard the destroyer HMS Wolfhound. Every 30 minutes during the passage across the English Channel the Wolfhound was attacked by Nazi dive-bombers. While the British gunners had no great success against the Luftwaffe’s planes, the attacks helped Tennant realize just how harrowing the Channel crossing would be.

Tennant recalled that as he went ashore at 6 pm to contact the British Army commanders in the town “the sight of Dunkirk gave one a rather hollow feeling in the pit of the stomach. The Boche had been going for it pretty hard, there was not a pane of glass left anywhere and most of it was still unswept in the center of the streets.”

Tennant swiftly assessed the docks as unusable and stationed his sailors along the beaches east of Dunkirk to act as shore police. He had found some British soldiers dazed by the Luftwaffe’s bombing while others ransacked private property, roaming in undisciplined packs.

Ashore for only two hours, Tennant made the first of several brilliant decisions, which would favorably impact the evacuation. At 8 pm, he notified Admiral Ramsay, “Please send every available craft to beaches east of Dunkirk immediately. Evacuation tomorrow night is problematical.” Thus, Tennant determined that the town of Dunkirk and its harbors were not going to be points of embarkation and informed Operation Dynamo’s control center in Dover of this fact. The beaches east of Dunkirk were to be utilized immediately, at least for the time being.

Also on the 27th, Belgium’s King Leopold negotiated an armistice with the Germans. At 11 pm, Gort was told that the Belgians would lay down their arms at midnight. In one hour’s time, a 16-mile gap would open on the left flank of the BEF between the Belgian town of Ypres and the sea. Brooke hurried into the breach at the head of the British II Corps and managed to reestablish a continuous line between Ypres and Dixmude, thereby maintaining the Dunkirk perimeter intact.

Evacuating From the East Mole

Demonstrating a true leader’s gift of flexibility, Tennant realized the evacuation process from the beaches was impossibly slow. Small groups of men were picked up here and there. In desperation, Tennant reexamined Dunkirk’s outer harbor and the beaches east of the town. Although the Luftwaffe had set Dunkirk’s piers and quays ablaze, the air attacks had completely ignored the two long breakwaters or moles that formed the entrance to the harbor. The clouds of smoke generated from the German air assault and the Wehrmacht’s artillery barrages on the town of Dunkirk hung low over the harbor impairing visibility to and from the air.

The moles were a mile apart at the land side and angled toward each other into the open water. Made of concrete pilings and covered with an eight-foot-wide boardwalk, the moles seemed to Tennant to present too great a risk to try to bring ships alongside them to tie up. However, if large numbers of men were to be evacuated by ship, there was no other way.

The west mole was only about 500 feet long, and the water at its near end seemed dangerously shallow. The east mole attracted Tennant’s attention as it ran some 1,400 yards out to sea. The base of the east mole ran right into the sandy beach at the town limits of Dunkirk near the holiday resort of Malo-les-Bains. Tennant saw that troops could be mustered on the dunes and beaches of Malo-les-Bains and marched out in disciplined groups onto the mole and along the walkway. There was no need for the men to enter the fiery inferno of Dunkirk itself. Under their own officers, supervised by Tennant’s naval shore party, the beleaguered troops could exit from their makeshift beach trenches right onto the evacuation ships.

During the evening of May 27, Tennant directed the steamer Queen of the Channel to enter the harbor and tie up at the east mole. The vessel eased into place alongside the breakwater, and to Tennant’s relief was quickly secured. This experiment demonstrated very quickly to Tennant that, although not ideal, the east mole was preferable to the alternatives offered on the open beach.

At 4:36 am on May 28, a signal went to Ramsay in Dover requesting an alteration in plans. Now Tennant wanted as many ships as possible, especially the fast modern destroyers, not off the beaches but alongside the east mole. This modification proved to be the pathway to safety for almost 200,000 of the 338,000 British and French troops embarked during the next several days.

Pownall was in a very somber mood. His entry for the day summed up some of the deficiencies of the BEF. “And so here we are back on the shores of France on which we landed with such high hearts over eight months ago. Months spent in working and preparing the force for the ordeal that was to come. I think we were a gallant band who little deserve this ignominious end to our efforts. There have been many difficulties to overcome, most of them due to the unreadiness of the Army for war and the neglect with which the statesmen and the country as a whole has treated the Army for two decades. Our struggle here was to overcome in a short space those severe handicaps—to prepare a semi-amateur army for an all-in struggle against the world’s greatest fighting machine. I think we can claim a great measure of success in our preparations. Yet here we are literally driven into the sea.”

Turning Point at Dunkirk

To some, May 29, 1940, is considered the turning point at Dunkirk. That morning Gort still thought further evacuation might become impossible since Dunkirk was under fire from German artillery, which was adding to the devastation already caused by the Luftwaffe. Yet as the day went on the prospects brightened. The arrival of French warships contributed immensely to the embarkation efforts. More than 47,000 men were evacuated from the Dunkirk mole and from the beaches that day, nearly three times as many as the day before.

Losses, however, were grievous at sea. Three destroyers were sunk, and six had been damaged. Numerous other vessels were hit during air attacks and torpedo runs by German E-boats. German artillery began ranging against the sea approaches to Dunkirk.

Admiral Ramsay ordered three destroyers to test the artillery against a new central navigation route (X) while minesweeping was still under way. The three destroyers were bombed from the air, but they drew no artillery fire. Minesweeping continued, and by mid-afternoon evacuation ships were ordered to utilize this new route since there was no imminent danger from German artillery.

The German Air Ministry situation report for this day read, “…The full force of the air attacks was directed against the numerous merchant vessels in the adjacent sea areas and the warships escorting them.” An important ramification of the Luftwaffe’s strategy was that attacks on the perimeter line and on the retreating armies virtually ceased, allowing more troops to arrive at the beaches relatively unhindered.

On the afternoon of the 29th, it was decided at the Admiralty that the naval organization off Dunkirk should be strengthened. It was not intended that Captain Tennant should be superseded as SNO; however, Rear Admiral W.F. Wake-Walker was appointed “for command of seagoing ships and vessels off the Belgian coast.”

While Admiral Wake-Walker was en route to his new station, the Admiralty came to the conclusion that the destroyer loss rate was unacceptable. The First Sea Lord, Admiral Dudley Pound, made the decision to withdraw his modern destroyers since his primary charge was the protection of Britain’s sea lanes and the destroyer flotillas were a vital component of that naval mission. Ramsay was allotted 15 remaining destroyers of older classes.

During the night of May 29, the British 4th Division reached Nieuport. It was incorporated in a combined Franco-British corps with orders to defend the sector from Bergues to Les Moeres. In the early hours of May 30, Eden sent secret instructions to Gort “authorizing him to capitulate when in his judgment … no further proportionate damage could be inflicted on the enemy.”

200,000 Troops Saved by June 1st

Ramsay was still trying to make sense of all the signals he was receiving at Dover. He needed to know if the east mole was still operational after the repeated bombing the previous evening. Ramsay sent the destroyer HMS Vanquisher to investigate early on the morning of the 30th, and the report was that it could still possibly be used.

The Army leaders were also creative in their attempts to facilitate the evacuation. The soldiers began to build ersatz piers out of trucks, Bren carriers, ammunition wagons, and other vehicles to enable the crews of the small boats to embark troops from deeper water. Clearly, the level of the tide would impact the success of these impromptu jetties. As a result of this ingenuity, the flow of men from the beaches steadily increased.

After meeting with Pownall and the chiefs of staff and service ministers on the 30th, Churchill decided that French troops must be given an equal opportunity to evacuate not only in their own vessels but in British ships. After meeting with Gort’s staff at Dover, Ramsay was told that the BEF perimeter would hold until early on June 1. With this information, Ramsay decided to continue evacuation through June 1 and perhaps longer.

Throughout the day, the evacuation continued and the numbers lifted kept rising despite the difficulties off the beaches and the temporary suspension of work at the mole, which Ramsay had rescinded. After conferring with the First Sea Lord, Ramsay convinced his superior to allow the modern destroyers to return to Dunkirk to hasten the evacuation. The tally on May 30 was 53,823 men being safely brought to England. More than half were evacuated from the open beaches by small vessels.

The British cabinet decided on May 31 that the commander of the BEF should return to England when the size of the force remaining on land was reduced to three divisions. Gort told the French commanders at Dunkirk, “My government has recalled me to London, but I am leaving General [Harold] Alexander behind with three British divisions which will act under your orders for the defense of the bridgehead.”

In a fractious exchange with the French commanders at Dunkirk, Alexander informed them of his intended plan: “I have been in touch with Mr. Anthony Eden. He has ordered me to cooperate with the French forces in the fullest measure compatible with the security of the British troops. I consider their existence seriously threatened and I am sticking to my decision to embark tomorrow, June 1st.” Thus, according to Alexander’s operations order, the perimeter was to be abandoned by 11 pm on May 31.

Ramsay was under increased pressure because embarkation from the beaches was deteriorating owing to changes in weather patterns. Also, evacuation from the mole was becoming more dangerous. Adding to this, Ramsay received a signal informing him that the final evacuation of the rear guard of the BEF was postponed to the night of June 1st, extending the evacuation efforts by at least an additional 24 hours.

Miraculously, the evacuation from the beaches improved with the wind and surf calming sufficiently. The makeshift jetties made by the Royal Engineers were significantly increasing the evacuation numbers from the beaches. Despite German artillery fire, the mole was still in use. On the day of Gort’s evacuation, 68,014 other men safely reached England. About one-third of this number were plucked from the beaches. By daybreak on June 1, a phenomenal 200,000 British, French, and Belgian troops had been embarked to England during Operation Dynamo.

Four destroyers were sunk in the first few hours of daylight on June 1. Another four were seriously damaged. In addition to the devastation wreaked upon the destroyer flotillas, steamers, minesweepers, and small boats of all varieties were listing or engulfed by fire.

The Admiralty suspended the evacuation effort at 7 am on June 2. Ramsay stated that he had ordered all ships to withdraw from Dunkirk before daylight. He wrote: “In these circumstances, it was apparent that continuation of the operation by day must cause losses of ships and personnel out of all proportion to the number of troops evacuated, and if persisted in, the momentum of evacuation would automatically and rapidly decrease.”

Once darkness occurred, however, ships would return to resume evacuation efforts.

The Last Rescues

Clearly, evacuation efforts would not be completed by the dawn of Sunday, June 2, as originally planned. The Dunkirk perimeter would hold as originally planned until midnight. In accordance with the instructions he had received from the war office, Alexander ordered the last remaining British troops to withdraw into Dunkirk harbor “with all available anti-aircraft and anti-tank guns and with such troops as had not yet embarked.”

It was Alexander’s intention to continue the evacuation during the night from the western beaches and Dunkirk, the rear guard retiring at dawn to Dunkirk itself. Wake-Walker, Alexander, and Tennant met to finalize plans for the overnight evacuation. All were made aware that the French were holding a line behind the remaining BEF troops through which the British rear guard would withdraw. Ramsay had ordered all efforts shifted to nocturnal loading. By midnight on June 1, another 64,429 men were evacuated to England.

Approximately 4,000 men of the BEF rear guard still remained ashore on June 2. Another 50,000 to 60,000 French troops were in Dunkirk itself or holding the ever-shrinking perimeter. Ramsay had only Dunkirk’s harbor and roughly a mile and a half of beach left for the evacuation; however, both of these sites were under continual air and artillery attack. He planned to lift another 25,000 troops under cover of darkness.

The last BEF evacuees were aboard ship by 11 pm. At 10:50 Captain Tennant loaded the last of his naval party onto a motor torpedo boat. Before leaving, he radioed Ramsay: “Operation Dynamo complete. Returning to Dover,” a message which was later abbreviated to the more triumphant “BEF evacuated.”

Alexander and Tennant toured the harbor and shoreline in a fast motor boat to make sure that not a single soldier remained to be taken off. Satisfied that there were none, they headed for England. The total number of men evacuated on June 2 was 26,256.

Once the BEF rear guard was lifted on June 2, there was a complete cessation of evacuation just prior to midnight. No ready explanation has been offered although numerous French troops remained in and around Dunkirk harbor. At 12:30 am on June 3, Wake-Walker radioed Ramsay that there were four ships at the mole but no French troops on the planks. At 1:15 am he signaled Dover, “Plenty of ships, cannot get troops.” After waiting past their scheduled departure times, the remaining ships sailed with no evacuees.

Ramsay ordered all his destroyers and many steamers to cross for embarkation attempts on the night of June 3. He believed there were approximately 30,000 French troops remaining for evacuation. Wake-Walker, supervising the crossing of the destroyers and steamers, was at the mole at 10 pm. These ships picked up the last of a few small British parties that had remained ashore. On June 3, another 26,746 men, the overwhelming majority being French, reached the safety of England.

338,226 Evacuated, 66,426 Lost

The evacuation was finally terminated in the early hours of June 4. The official tally shows 338,226 Allied troops brought out, 228,500 British and the rest mostly French. Records reveal that 243 ships were sunk. Gort lost 66,426 men, including 11,014 killed, 14,074 wounded, and 41,338 taken prisoner or missing. The BEF abandoned almost all its heavy equipment, including artillery, motor transport, and armor.

Churchill’s classic truism that “wars are not won by evacuations” remains important as it applies to Dunkirk, especially since it has been mythologized as a “miracle.” Churchill understood the unpreparedness of the Army now facing a possible invasion.

Montgomery further asserted, “The campaign in France and Flanders in 1940 was lost in Whitehall in the years before it ever began, and this cannot be stated too clearly or too often.”

One must remember that from May 24 to May 28, 1940, Churchill was waging a simultaneous political battle in London with Lord Halifax, his foreign secretary and adversary in the halls of government. The successful evacuation of the majority of the BEF was crucial not only for Britain’s morale but also for Churchill to remain in power.

For Gort, Dunkirk was the end of his career as a fighting general. Despite bringing out the bulk of the BEF, Churchill did not favor him. In 1942, Gort was named governor-general of Malta, where he characteristically displayed tenacious courage. His career ended as high commissioner in Palestine and Trans-Jordan in 1945, and he died on March 31, 1946, just before his 60th birthday.

As summed up by historian A.J. Barker, “Vice Admiral Bertram Ramsay, Flag Officer Dover, faced responsibilities which were to tax his knowledge, his energy, his ingenuity and above all his ability to persuade others that his decisions were the right ones.” Ramsay, who subsequently became the architect of the Royal Navy’s role in the Normandy invasion, died in a plane crash near Paris on January 2, 1945.

Captain Tennant resumed his command of HMS Repulse, which was sunk along with the battleship HMS Prince of Wales by Japanese planes off the coast of Malaya on December 10, 1941. Tennant was promoted to rear admiral and appointed to Ramsay’s staff in January 1944. He then went to work on the Mulberry artificial harbor project, which enabled a substantial amount of critical supplies to be brought ashore following the D-Day landings in Normandy in June 1944.

Originally Published December 1, 2016

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments