by G. Paul Garson

After September 1, 1939, and Germany’s invasion of Poland, a trickle of so-called “death cards” began appearing in homes across the Third Reich. Each of the 2- by-4.5-inch paper rectangles bore the image of a soldier killed in action and was posted to friends and relatives by the deceased’s family. The trickle increased in 1940 as the blitzkrieg swept through France. It became a torrent after June 22, 1941, and Operation Barbarossa, Nazi Germany’s doomed effort to conquer the Soviet Union. One such death card was issued in the name of Josef Hamperl, the resident of Kolenzdorf having fallen on August 23, 1944, in the south of France two days after U.S. forces had reached the Seine River north and south of Paris as the Allies pushed toward the borders of Germany. The grenadier was 19. He was also a motorcyclist, his military life spent, literally, on two wheels. His death card photo shows him wearing his riding goggles, the young soldier one of thousands who rode to war on two or three-wheeled German motorcycles.

After September 1, 1939, and Germany’s invasion of Poland, a trickle of so-called “death cards” began appearing in homes across the Third Reich. Each of the 2- by-4.5-inch paper rectangles bore the image of a soldier killed in action and was posted to friends and relatives by the deceased’s family. The trickle increased in 1940 as the blitzkrieg swept through France. It became a torrent after June 22, 1941, and Operation Barbarossa, Nazi Germany’s doomed effort to conquer the Soviet Union. One such death card was issued in the name of Josef Hamperl, the resident of Kolenzdorf having fallen on August 23, 1944, in the south of France two days after U.S. forces had reached the Seine River north and south of Paris as the Allies pushed toward the borders of Germany. The grenadier was 19. He was also a motorcyclist, his military life spent, literally, on two wheels. His death card photo shows him wearing his riding goggles, the young soldier one of thousands who rode to war on two or three-wheeled German motorcycles.

These military vehicles have been going to war for as long as they’ve been around: American Harley-Davidson and Indian; British Triumph, BSA Matchless, and Norton; Italian Motor Guzzi and Gilera; French Terot and Gnome Rhone; Belgian FN and Gillet. More manufacturers were producing them by World War II. If you had a war to go to, motorcycles would get you there, often faster and through terrain inaccessible to other vehicles.

The German military was the largest employer of motorcycles during World War II. In addition, as German forces swept across conquered lands they acquired a wide array of British, French, and Belgian machines, painted them Wehrmacht gray, and sent them into battle. German military motorcyclists played an important role either as solo couriers or as scouts, as teams of tank hunters, or in divisions of rifle troops.

What did the German soldiers think of their warhorses? One rider of a motorcycle manufactured by NSU wrote back to the company the following words of praise, often echoed by his comrades. “On September 21, it has been five years since I bought it new at your Stuttgart branch, where I worked as a mechanic since August 1939. Since the end of August, I have been in Wehrmacht service with the motorcycle, which I myself have always driven since then. During the four years of my private driving, the machine always functioned to my complete satisfaction, as it has now, since I have been drafted. In this year I have driven it 20,000 km, at first in the Polish campaign, then during service in the operational area of the western front and on duty in France. During the campaign in France I drove about 7,000 km…. If possible, I want to buy back the machine after the end of the war we have been compelled to wage.”

This letter was penned in the early part of the war when Germany seemed invincible. There is no word if the satisfied customer was ever able to claim his beloved motorcycle.

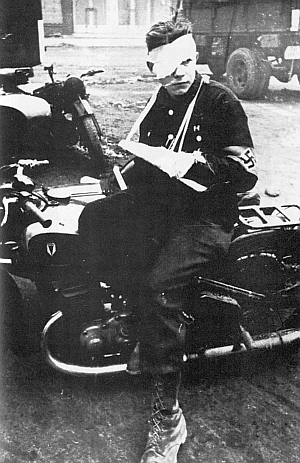

During the campaigns that spread across Europe and into the Soviet Union, motorcycle troopers served a variety of functions including chauffeuring officers, delivering dispatches and even hot meals, and scouting on patrol. Motorcycles also were point vehicles taking the brunt of battle, sometimes as specially equipped tank destroyers. As with all motorcyclists, there was a kinship among these soldiers who called themselves “kradfahrer.” They rode exposed without the armor plating of the Panzers, without the safety of hundreds of foot soldiers beside them—moving targets, as it were, or sniper magnets. And then there were minefields, artillery fire, and strafing aircraft to contend with. (Learn about these and other legendary military vehicles used during the war inside the pages of WWII History magazine.)

To Improve Their German Motorcycles, BMW Sent Their Designers to the Front Lines

The other enemy was inclement weather, particularly on the Eastern Front. By autumn, the roads had turned into nearly impassable bogs, the fields over which the motorcycles traveled turning into seas of mud three feet deep at times. Pack horses sank to their bellies, boots were sucked off the soldiers’ feet. Motorized forces that had once traveled over 70 miles in a day now were lucky to make 10. By winter temperatures fell to minus 40 degrees Farenheit, engine oil and exposed soldiers freezing solid. Some 113,000 cases of frostbite were reported. Some German motorcycle riders benefited from special heating systems grafted onto their bikes, including foot and hand warmers. They, along with the foot soldiers, ate horse meat provided by over 100,000 animals that died in the freezing cold. But the two-wheeled iron horses pushed on.

The other enemy was inclement weather, particularly on the Eastern Front. By autumn, the roads had turned into nearly impassable bogs, the fields over which the motorcycles traveled turning into seas of mud three feet deep at times. Pack horses sank to their bellies, boots were sucked off the soldiers’ feet. Motorized forces that had once traveled over 70 miles in a day now were lucky to make 10. By winter temperatures fell to minus 40 degrees Farenheit, engine oil and exposed soldiers freezing solid. Some 113,000 cases of frostbite were reported. Some German motorcycle riders benefited from special heating systems grafted onto their bikes, including foot and hand warmers. They, along with the foot soldiers, ate horse meat provided by over 100,000 animals that died in the freezing cold. But the two-wheeled iron horses pushed on.

In an effort to improve their motorcycles, BMW sent designers to the front lines. One such designer reported the following: “While we were following the movement of the front in daily stages, we spent the nights in tents on the steppes…. We had crossed the Don, and then gone in the direction of Stalingrad, and we sought out the field repair shops, which operated in the most primitive conditions, directly behind the front line. There the machines were examined and reports on the troops’ experiences were taken. My opinion was correct. The machines went under the liquid mud, which flowed over the motors by the bucketful and was sucked into the low-lying air filter, ruining it—the mud got into the motor, and often the oil pans no longer held oil, but only sand….

“One clearly saw the enormous difference between the soldiers out there on the front and the back-line people, who were real bureaucrats, while the troops were trying to build one usable machine out of 10 ruined ones. The new oil filter on my machine, screwed onto the tank high up, performed without trouble. But the improvements—although we worked on them day and night to change the whole series at once—were no longer sufficient for Russia. Stalingrad had changed everything. All the machines that went to the east were lost, at least we never heard of them again.”

“One clearly saw the enormous difference between the soldiers out there on the front and the back-line people, who were real bureaucrats, while the troops were trying to build one usable machine out of 10 ruined ones. The new oil filter on my machine, screwed onto the tank high up, performed without trouble. But the improvements—although we worked on them day and night to change the whole series at once—were no longer sufficient for Russia. Stalingrad had changed everything. All the machines that went to the east were lost, at least we never heard of them again.”

At war’s end, many if not most of the German motorcycles, along with their riders, did not return home. The grim words of a German motorcyclist’s poem called The Hat, The Table and the Broom, relate the sentiments of these extraordinary soldiers.

In the East the cyclist’s lot was not light

and I often believe the prophet was right,

When I saw a cyclist engulfed in the flood,

Trying to free his machine from the mud.

And when I saw the man around Riga again,

A frustrated cyclist, with puzzled brain,

Stood there with a cycle that just wouldn’t start

A load on his mind and a pain in his heart The man said: “Your faith is delusion, of course.

You can only depend on the great iron horse,

Or a horse with a saddle, if not a train’s around.

In no other way can you cover this ground.

The Germans’ lightning war required machines of high caliber in more ways than one. Although horses and even bicycles carried battalions of combatants, as did trucks and tracked vehicles, motorcycles led the way. These were often purpose-made BMW and Zundapp military bikes, as well as civilian models made by NSU and DKW and a host of other manufacturers, that “served” either by contract or requisition.

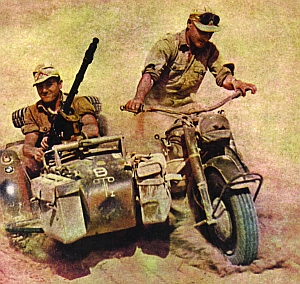

For heavy-duty sidecar use, the German military relied upon the Zundapp KS750 and the BMW R75, both motorcycle manufacturers producing their own sidecars although those built by Stoye, Royal, and Steib were also employed. Next in line were the motorcycles manufactured by DKW and NSU. Non-German motorcycles, bought under license, included the Triumph, with more than 12,000 250cc units built in Nuremburg, which was also home to Steib sidecars of the era, and later the site of the war crimes trials.

For heavy-duty sidecar use, the German military relied upon the Zundapp KS750 and the BMW R75, both motorcycle manufacturers producing their own sidecars although those built by Stoye, Royal, and Steib were also employed. Next in line were the motorcycles manufactured by DKW and NSU. Non-German motorcycles, bought under license, included the Triumph, with more than 12,000 250cc units built in Nuremburg, which was also home to Steib sidecars of the era, and later the site of the war crimes trials.

By 1938, some 200,000 motorcycles were produced annually in Germany and the adjacent areas it had annexed. The principal manufacturers were BMW, DKW, NSU, Triumph (under German license), Victoria, and Zundapp. In comparison, BMW alone posted 93,836 units sold for 2004.

“Type Russia,” the R75 Sidecar, was Literally Unstoppable. (Until it Encountered the Snowdrifts Outside Stalingrad.)

The BMW motorcycle, first launched in 1923, had broken the motorcycle speed record with a supercharged 750 in 1937, reaching 173.68 miles per hour. In June 1939, three months before to the start of World War II, German rider George Meier won the famous British Isle of Man TT, the first for a foreign rider on a foreign bike. In addition to the vaunted 750cc R75, BMW also supplied the military more than 36,000 side valve R12 motorcycles. The Wehrmacht used the following BMW models: R4, R12, R23, R35, and R75.

The BMW motorcycle, first launched in 1923, had broken the motorcycle speed record with a supercharged 750 in 1937, reaching 173.68 miles per hour. In June 1939, three months before to the start of World War II, German rider George Meier won the famous British Isle of Man TT, the first for a foreign rider on a foreign bike. In addition to the vaunted 750cc R75, BMW also supplied the military more than 36,000 side valve R12 motorcycles. The Wehrmacht used the following BMW models: R4, R12, R23, R35, and R75.

Also known as the “Type Russia,” the R75 sidecar was literally unstoppable until it encountered the snowdrifts outside Stalingrad. Designed between 1939-1941, the tank-tough R75, with its crankshaft-driven sidecar, proved itself to be a major success, boasting 52 miles to the U.S. gallon, a range of 225 miles, and a carrying capacity of over 1,000 pounds, about equal to its own 929-pound weight. Specifications included a 745cc air-cooled four-stroke overhead valve twin-cylinder engine. An 8-speed transmission had two reverse gears as well. Top speed was a reported 60 miles per hour. The shaft final drive featured a split-tongue differential, two thirds going to the bike, one third to the sidecar. But R75 arrived too late in the war and in too small numbers (16,500) to affect the final outcome; its factory in Eisenach was destroyed in 1944 by Allied bombing. Today, the R75 is a most sought after collectible, fetching as much as $45,000.

Established in Zschopau, near the city of Chemnitz in 1919 by a Danish entrepreneur, DKW became the largest brand not only in the German Reich, but in the world. In 1932 the company merged with Auto Union, composed of DKW, Audi, Horch, and Wanderer. Postwar DKW later became MZ, then more recently Hercules while retaining the DKW name because of its reputation. German military models included the RT125 and NZ350.

The marque of this manufacturer was derived from the city in which its motorcycles were made, Neckarsulm, and thus the letters NSU. Initially, in 1873, the company produced knitting machines, then moved on to bicycles and automobiles as well as V-twin motorcycles. NSU built prototypes that eventually appeared as the Volkswagen, Hitler’s “people’s car.” German military models included the Pony 100, 201 ZDB, 251 OSL, 351 OSL, 501 OSL, 601 OSL, 501 TS, and 601 TS.

Victoria started out as bicycle maker in 1886, introducing its first motorcycle in 1899. The Nuremberg facility later added an engine factory in Munich, the engine designed by an ex-BMW engineer. In 1926, the Victoria supercharged racer broke the speed record with 104 miles per hour. In the 1930s, the company began producing two- and four-stroke machines from 98cc to 248cc. German military units included the KR 35 WH and K 6.

Established in 1917 to make fuses for artillery guns during World War I, Zundapp began building high-quality bikes in 1919, both two- and four-strokes. By 1933 the company had produced 100,000 motorcycles. Between 1938-1941, more than 18,000 Zundapp 600cc KS W sidecar rigs were built for German military use. The best known Zundapp was the KS 750 flat twin-built exclusively for the Army. German military models included the DB 200, K 500W, KS 600 W, K 800 W, and KS 750.

The KS 750 went into production in 1940 with approximately 18,695 units built. Its weight was 920 pounds with a top speed of about 60 miles per hour. It was frequently equipped with an MG-34 machine gun attached to the sidecar.

Josef Stalin Himself Established IMZ-Ural in 1941, Specifically to Build Copies of the BMW R75 as Combat Vehicles for the Red Army

Before the outbreak of hostilities between Germany and Russia, a joint venture of sorts involving motorcycle sidecar production took place between the eventual adversaries. The arrangement served to outflank the Treaty of Versailles restrictions that prohibited Germany from any form of military vehicle production, including large-capacity motorcycles and sidecars. However, while BMW was already developing more advanced R75 engines, it supplied the Soviets with the older R71 design.

Josef Stalin himself established IMZ-Ural in 1941, specifically to build copies of the BMW R75 as combat vehicles for the Red Army; these were designated the Soviet Ural M72, almost identical to the German BMW R71. Ultimately some 10,000 of the M72s, fabricated in a Siberian factory east of the Urals, went to war. After the collapse of the Third Reich, the Soviets appropriated all BMW tooling and engineering designs, including the R75 motorcycle OHV engine and dual-wheel drive system technology, which was then used to create the more advanced Russian “Ural” and “Dnepr” models. The Ural region of Russia is still home to modern Urals. In the mid-1950s, civilian Urals went into production. In 1993, updated mechanically and cosmetically, they were introduced into the United States. Recent estimates assert that approximately three million Urals are now serving on- and off-road duties in Eastern Europe and Russia.

Josef Stalin himself established IMZ-Ural in 1941, specifically to build copies of the BMW R75 as combat vehicles for the Red Army; these were designated the Soviet Ural M72, almost identical to the German BMW R71. Ultimately some 10,000 of the M72s, fabricated in a Siberian factory east of the Urals, went to war. After the collapse of the Third Reich, the Soviets appropriated all BMW tooling and engineering designs, including the R75 motorcycle OHV engine and dual-wheel drive system technology, which was then used to create the more advanced Russian “Ural” and “Dnepr” models. The Ural region of Russia is still home to modern Urals. In the mid-1950s, civilian Urals went into production. In 1993, updated mechanically and cosmetically, they were introduced into the United States. Recent estimates assert that approximately three million Urals are now serving on- and off-road duties in Eastern Europe and Russia.

After the Chinese Communists acquired Russian copies of German World War II BMW’s from the Soviets, they eventually came up with their own variations, which were used by the Chinese Army. In 1957, the Chinese M72 went into production under the name of Chang Jiang 750, initially incorporating a number of Russian M72 parts.

The Chang Jiang 750 has been built in the millions since then and is rather sturdy. They have been manufactured in the same factory that produced military CJ 6 airplanes, 105mm artillery, and Model 56, 60, and 62 battle tanks in the heartland of JianXi province. The Chang Jiang 750 is considered to be the earliest vintage sidecar motorcycle still in production, and while no longer in use by the regular Chinese Army, it is still employed by the local PLA and police. The motorcycle is currently available from various sources.

Even America’s legendary Harley-Davidson Motor Co., at the behest of the U.S. military, produced a copy of the Wehrmacht’s vaunted BMW motorcycle. Known as the XA model, it featured the BMW signature flat twin engine with shaft drive. The U.S. Army ordered 1,000 of the XA’s at $870 each; however, it dropped the order in favor of the less complicated and less expensive overhead valve Harley-Davidson WLA, of which some 88,000 were ultimately built. A prototype sidecar design, also using the German “boxer” engine design and shaft-driven sidecar wheel, faded from the planning stages with the advent of the all-conquering Jeep.

First-time contributor G. Paul Garson is a motorcycle enthusiast who resides in the Los Angeles area.

Originally Published November 18, 2015

great motor cycles bmw all the way. i have a r1100r bike year 2000. runs so good and yes my father was a tanker in ww2. he saw some bmw bikes in the war. i would like to go to the bmw plant to see them built they are good, no they are the best thing every built. thank you, my name harold.

damn, unfortunately we didn’t end up speaking German after the war otherwise we would have been in space right now.