By Richard A. Beranty

Donald R. Lobaugh was a juvenile delinquent, a kid sent to reform school when he was 16 years old. People in his hometown called him a bad egg and predicted he would not amount to much. But he did, receiving the Medal of Honor posthumously for his actions on July 22, 1944, in the jungles of New Guinea, where he sacrificed his own life to help save 39 men in his platoon when they became trapped behind enemy lines during a Japanese offensive.

Lobaugh’s story is also a story of the early history of the U.S. 32nd Infantry Division in World War II. The 32nd Division was one of the first American forces sent overseas to battle Japanese aggression in the Pacific.

It was one of the darkest periods in modern American history. Hitler and his Fascist legions had overrun most of Europe, declared war on the United States, and set their sights on the conquest of the Soviet Union. In the Pacific, Japanese militaristic might had destroyed the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor and dominated the landscape from the Aleutian Islands in the north to New Guinea in the south. The fate of the free world literally hung in the balance.

To counter the threat that Germany and Japan posed, the U.S. government took action in August 1940, by mobilizing into federal service the country’s 18 marginally trained and woefully underequipped National Guard units. One of the first to be called up was the 32nd “Red Arrow” Division, comprising mostly citizen soldiers from the small towns and rural farms of Michigan and Wisconsin. Following field maneuvers in Louisiana and later in the Carolinas, the 32nd received orders in late December 1941 to proceed to embarkation points in New York bound for Northern Ireland. They were to be part of Operation Magnet, a concentration of forces slated to take part in Operation Torch, the Allied effort to dislodge Axis troops from North Africa.

But a last-minute decision made by the Combined Chiefs of Staff of the U.S. War Department in March 1942 changed the division’s direction, setting into motion a 180-degree turnaround. Placed onto troop trains, the 32nd Infantry Division headed west in what only can be described as a logistical miracle. In just three weeks, its men and equipment were transported 3,000 miles and sailed from San Francisco on April 22, arriving in Australia May 14. Under the command of General Douglas MacArthur, the division (along with Australian troops) would confront Japanese aggression in Papua New Guinea and neutralize the threat of an invasion of Australia. The task was a formidable one on paper, but even more so in the disease-infested swamps and jungles of New Guinea against an experienced and jungle-savvy enemy.

A Delinquent Teenager Sent to Reform School

Some two years prior to the division’s mobilization to Australia, a 15-year-old Pennsylvania boy, Donald R. Lobaugh, was getting into trouble with the law in the small town of Freeport, located along the Allegheny River just northeast of Pittsburgh. A skinny, tow-headed youth, Lobaugh was one of eight children whose mother, Ida, was left a widow in 1939 when a hit-and-run driver killed her husband. Penniless and faced with the daunting task of raising five girls and three boys on her own, Mrs. Lobaugh did not like the path her youngest son was taking. His main passion, it seemed, was being truant from school.

“He was what we called at that time a delinquent,” remembered William Galino, a former schoolmate of Lobaugh. “Back then, a delinquent was someone who smoked cigarettes and played hooky.”

But Lobaugh’s mischief making would eventually extend beyond the classroom. In 1940, police arrested the 16-year-old for his involvement in the theft of an automobile, and most people in his hometown were sure, more than ever before, that the youngest Lobaugh boy “wouldn’t amount to much.” He was ordered to appear before a fair-minded juvenile court judge named J. Frank Graff, who sentenced the rebellious teenager to attend George Junior Republic, a privately run reform school in Grove City, Pennsylvania, to which boys were routinely sent by the courts after minor infractions with the law.

“Donald’s hatred of school, his persistent record of truancy and potentially evil associates, might lead an otherwise useful citizen to a life of crime,” remarked the judge in his order.

“His Heart Was Set on Being a Sailor or a Soldier”

Lobaugh arrived at George Junior Republic on September 12, 1940, determined to cooperate as little as possible with school officials. He fought off their every attempt to make him a better citizen. After six weeks of his antisocial and belligerent behavior, the school’s superintendent, Arthur T. Prasse, decided it was time to personally intervene.

“I took the boy over my knee and gave him a good spanking—the sort of thing his dad would have done if he’d been alive,” said Prasse, who in 1950 would become commissioner of corrections for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. “[Afterward] Donald and I had a long talk together for a couple of hours. Then we took in a movie, just the two of us, and had a couple of ice cream sodas. From then on came Donald’s real reform and rehabilitation. Before he left us to join the Army he held a high elective office in the citizen government and was an outstanding student.”

Enlisting in the military, however, was not a given for someone with a police record, and the armed services were not in the habit of drafting those in reform school. Determined to prove his worth, Lobaugh first sought to enlist in the Army. He was denied. Then he tried the Marines with the same result. The Navy said the same. Finally, Superintendent Prasse pulled some strings with Army officials, assuring them of Lobaugh’s merits and determination. He was allowed to enlist in the U.S. Army, left reform school on February 11, 1942, four days after his 18th birthday, and entered basic training at the Infantry Replacement Training Center at Camp Wheeler, Georgia, on May 15.

“His heart was set on being a sailor or a soldier,” wrote Superintendent Prasse to Lobaugh’s mother years later. “He always wanted to play his part, and to show the world his true character and makeup.”

The 17 weeks Lobaugh spent in basic training left an impression on the former “delinquent,” explained Galino, who had not seen his onetime schoolmate in more than two years when the two met in the summer of 1942.

“I remember talking to him when he came home after basic training,” Galino said. “He was very proud of his accomplishments. He told me how he had learned to read a map, and how to judge distances in the field. You see, when he was in school, he didn’t have to learn. Teachers didn’t force him to learn. Anybody could put their head down in class and fall asleep. But in the Army, they made him learn. That, I think, was the difference.”

The situation facing the Allies in the Pacific when Lobaugh entered the service bordered on desperate. Japanese military forces had gained control of half of the Pacific and were firmly established on the Asian mainland. But events would transpire over the next two months that provided some optimism for the Allied cause. First, the U.S. Navy in May essentially fought the Japanese to a stalemate in the Battle of the Coral Sea. More importantly, the battle thwarted any immediate plans the enemy had of landing an invasion force at Port Moresby. Second, the Navy’s lopsided victory at Midway in June was a devastating blow to the enemy’s naval capabilities. Japan would never recover from its loss of four aircraft carriers and many of its most experienced pilots.

Still, grave concerns plagued the Allies, particularly the enemy’s two-pronged drive in the South Pacific—one through the Solomon Islands and the other across New Guinea. If left unchecked, Japan would have the bases it needed to cut supply lines from America to Australia, making an invasion of the Australian continent, just 300 nautical miles from southern New Guinea, all the more probable.

Capturing the vital seaport of Port Moresby was critical to any such hopes harbored by Japanese war planners. To achieve their goal, 11,400 troops were landed at Buna, Gona, and Sanananda along Papua New Guinea’s northern coast in late July 1942. Their mission was to trek 120 miles to Port Moresby over the Papuan peninsula via the Kokoda Track, which crosses a nightmarish expanse of terrain that includes the forbidding peaks of the Owen Stanley Mountains.

The 32nd Division in Port Moresby

Japanese soldiers soon learned that few places on Earth are so inhospitable for troops, as the mountain trail narrowed at times to no more than a yard in width with 1,000-foot slopes on either side. Trees in the area were so overgrown with moss and vines that sunlight was unable to penetrate to the rotting jungle floor. And tropical rains, which total more than 300 inches a year, filled jungle swamps and turned small streams into torrents of water.

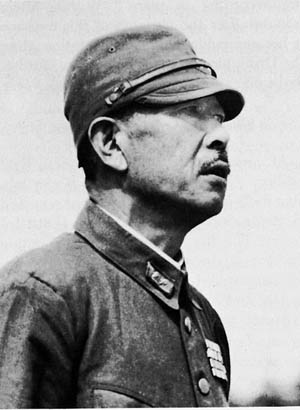

Nature’s forces notwithstanding, the Japanese advance, which included General Tomitaro Horii’s highly vaunted South Seas Detachment, also had to battle its way to Port Moresby, as defense of the area was given to Australian troops and local Papuan militia. Nevertheless, the force moved southward from the coast, proving that a determined and well-led army might be slowed but would not be stopped. By the first week of September, it had pushed the small number of Australian defenders back to just 30 miles from Port Moresby.

But the Japanese advance proceeded no further. Physical exhaustion from the arduous march and battles with Australian troops had taken their toll on the men. So, too, did a lack of food and water and the daily bombing and strafing by the U.S. Fifth Air Force. With General Horii’s fighting force crippled and no reinforcements coming because of the reverses suffered by the Japanese on Guadalcanal, Imperial Headquarters instructed Horii to lead his force back to the Buna-Gona area and await reinforcements for a future attack on Port Moresby.

Horii reluctantly agreed to do so, with the Australian 7th Division, recently recalled from the Middle East, close on his heels.

With the Port Moresby area safe from enemy attack and Japanese forces retreating across the island’s interior regions, General MacArthur decided that the best way to defend Australia was to hold New Guinea and eliminate the Japanese presence in Papua. On September 13 he ordered to Port Moresby the 32nd Division, which for four months had been stationed in Australia as part of I Corps under the command of Maj. Gen. Robert L. Eichelberger. Assembling a hodgepodge of an air armada, which included Douglas and Lockheed transports, planes from the Australian civil airlines, and recently overhauled Army bombers, part of the division was airlifted to Port Moresby while the remainder was ferried to the area by sea.

By the end of September, the division’s transfer was completed, minus its four artillery battalions. With the exception of a lone 105mm howitzer, its eight-man crew, and 200 rounds of ammunition, transportation difficulties kept the division’s 47 remaining long guns in Australia for the entire Papuan campaign.

6,500 Japanese Soldiers in Buna

MacArthur next had to decide how to effectively transfer the 32nd to the Buna area, where the Japanese had been busy erecting defensive positions. His initial plan called for an overland trek along the Kokoda Track, but General Edwin F. Harding, commanding general of the 32nd, and General George C. Kenney, commander of the Fifth Air Force, persuaded MacArthur that an air transport would ensure speed and would not sap the strength of division troops. As the Australian 7th Division continued its push of the enemy back toward the coast, leading elements of the 32nd began their air movement to the northeast coast of Papua in early October, landing at several quickly improvised airstrips at Pongani, about 65 miles from Buna.

Some 32nd Division troops did not make the transfer by air. One battalion drew the hard-luck assignment of crossing the Papuan peninsula on foot. It took the 2nd Battalion, 126th Infantry Regiment, 42 days to complete the march along the Kokoda Track and over the Owen Stanley Mountains.

By mid-November, the sick, starving, and exhausted remnants of the Japanese force, which had so confidently started its overland march to Port Moresby in July, had completed construction of its defensive positions in the Buna area. Theirs had been a miserable ordeal, traversing the Papuan peninsula and back, and many men had been lost to the elements, including General Horii, who drowned when his log raft overturned while crossing the swift waters of the Kumusi River. With the addition of 2,000 fresh troops from China, Hong Kong, Java, and Formosa, Japanese strength in the Buna area totaled about 6,500 men who were ready to make a do-or-die stand against their enemy.

“The Japanese Line at Buna Was, in a Way, a Masterpiece”

The 32nd Division’s baptism of fire in World War II began on November 19, 1942, when two battalions of the 128th Regiment, during a torrential storm, attacked the right of Japanese positions at Cape Endaiadere, east of Buna. With the Australian 7th Division pressuring the enemy on the left in the Gona-Sanananda area, it was the start of a two-month battle of attrition that perplexed everyone from MacArthur on down.

As the official U.S. Army record explains, superiority in troop strength does not always ensure a rapid victory. “The Japanese line at Buna was, in a way, a masterpiece. It forced the 32nd Division to attack the enemy where he was strongest.”

The text describes the area as a series of bunkers built in locations that utilized the jungle terrain and existing trails to force any attack into planned fields of fire. “The Japanese had developed a well-prepared, but rather shallow position, extending for over ten miles along the coast. It consisted of basically three defensive groups—one at Gona, one in the Sanananda point area, and one in the Buna area—but the lateral communication between them along the shore was much superior to that of the attackers struggling through the inland jungles and swamps. These terrain features inevitably canalized the attacks into advances on narrow fronts, which were well covered by enemy fields of fire from prepared positions. These positions were usually dug in very little because water was everywhere present, a few feet below the surface of the ground. They were, however, protected all around and overhead by solid construction that included heavy coconut logs, steel oil drums filled with sand, and steel rails—all covered with earth and vegetation that made them almost indistinguishable from the surrounding country. These bunkers varied in size and were often mutually supporting. There were also some concrete and steel pillboxes.”

The 32nd Division’s “Failure” at Buna

The complete destruction of Japanese forces in the Buna area was a nightmare for American and Australian forces, as fighting there concluded on January 22, 1943. It was estimated that at one point the enemy lost 100 soldiers a day from starvation. So desperate were their efforts to defend the area that Japanese soldiers stacked corpses of their comrades outside pillboxes for added protection from Allied bullets. They also piled dead bodies inside their bunkers to stand on while they fired.

Casualties for the 32nd Division included some 600 killed, nearly 2,000 wounded, and 7,500 listed as sick. Of its original strength of 11,000 officers and men, total losses almost equaled that number. The hardest hit was the 126th Infantry Regiment. It entered the battle with 131 officers and 3,040 enlisted men. By late January it had just 32 officers and 579 men fit for duty.

Much went wrong for the Americans fighting at Buna, and debate naturally centered on why it took two months to eliminate a numerically inferior enemy force concentrated in such a small area. General MacArthur’s headquarters was quick to point a finger at the division’s leadership for failing to take the area in a timely fashion and made wholesale command changes, including General Harding, the division’s commander.

Command mistakes aside, the division’s “failure” at Buna was due to a litany of problems that plagued the 32nd from the outset of the campaign to its conclusion. The list is extensive, starting with a fragmented command structure that put some U.S. troops under the control of Australian commanders and the jealousy and animosity that go with it. It was also the result of inadequate air support, at times being nonexistent when needed and at other times causing casualties to Allied troops.

Other problems abounded: terrain difficulties hampered the delivery of food, ammunition, and medicine; a critical lack of armored, artillery, and mortar support vexed and confounded advancing riflemen; torrential rains washed out trails, made small streams impassable, and filled swamps with water that was often neck high; a host of diseases including malaria, dengue fever, tropical dysentery, and skin ulcers sickened nearly every man; communication breakdowns were common from one unit to another; and division troops, made up mostly of young men from America’s heartland, had received no training in jungle warfare. Along with enemy air attacks and the fanatical efforts of the Japanese soldiers, all of these factors contributed to the difficulty of the fighting at Buna.

Afterward, MacArthur made a terse promise: “No more Bunas.”

8,000 Cases of Malaria in the 32nd

With the Papuan campaign concluded, men of the 32nd Division returned to Australia in early 1943, and from February through October underwent a period of reorganization, resupply, rehabilitation, and retraining.

Major General William H. Gill, who had assumed command of the division on March 1, described this period in his 1953 memoirs. “The troops had taken part in the Papuan campaign and were in bad shape. I think somewhere in the records it will be shown that almost 8,000 had malaria; certainly the morale of officers and men was low. The men had to be cured in body and mind before any effective training for renewed combat could be accomplished.”

The effort to eject the Japanese from New Guinea was renewed in January 1944 and continued over the next seven months as American troops made many amphibious landings along the country’s northern coast and offshore islands, attacking some and bypassing other Japanese strongholds. From east to west, enemy bases fell in succession: Saidor, Aitape, Hollandia, Wakde, Biak, Noemfoor, and Sansapor.

The two biggest prizes in these operations were at Hollandia, with its extensive naval facilities, and 120 miles to the east at Aitape, which featured two airstrips and would also serve as a buffer should the Japanese attack Hollandia from the east. Both of these enemy installations were attacked on April 22; the U.S. 24th and 41st Divisions landing in the Hollandia area, and the 163rd Regimental Combat Team from the 41st Division at Aitape. The areas were quickly secured with small losses in American lives.

As part of MacArthur’s plan, the Japanese Eighteenth Army, which was positioned in the Wewak area of northeast New Guinea, was bypassed and left isolated. Australians opposed its eastern flank while U.S. forces occupied positions to its west. With some 55,000 men under the command of General Hatazo Adachi, these troops were hurting in the worst way from malnutrition, diseases, and a lack of supplies.

The 32nd at Aitape

On April 23, just one day after the American landings at Aitape, elements of the 32nd Division began coming ashore to relieve the 163rd Regimental Combat Team, which was slated to take part in the Wakde-Sarmi operation 250 miles to the west the following month. In two weeks the landings were completed, marking the first time since it initially faced combat nearly two years earlier at Buna that the entire 32nd Division, with all of its attached units, operated as a whole on a single mission.

From the start of 32nd Division operations at Aitape, very little in the way of enemy contact was reported, allowing engineers to convert the captured airstrips into a major fighter base. But by early June the division had extended its perimeter to the western banks of the Driniumor River, 15 miles east of Aitape, and contact with Japanese patrols was becoming more frequent. In an attempt to slow the Americans’ westward advance along New Guinea’s northern coast, Adachi picked 20,000 of his healthiest troops, artillery included, to march from Wewak and attack American positions toward the Driniumor. Over the next two months, some of the most desperate and exasperating fighting in the New Guinea campaign occurred.

Preparing for a Japanese Offensive

By this time, Private Donald R. Lobaugh, who would become one of 11 Medal of Honor recipients from the 32nd Division during World War II, was freshly arrived from the States. Following basic training at Camp Wheeler, he had been assigned to Company A, 8th Engineer Battalion, then volunteered for the Army’s jump school where he earned his parachute. He was then sent, like thousands of other Americans, to Australia as an infantry replacement, assigned to Company I, Third Battalion, 127th Infantry Regiment, 32nd Division, and came ashore at Aitape in early May.

As a result of codebreaking efforts, interrogations of captured Japanese soldiers, and the increased number of enemy encounters near the Driniumor, Allied headquarters was certain that Adachi was ready to launch a major offensive in the Aitape area. General Walter Krueger, U.S. Sixth Army commander, responded to this threat by sending in reinforcements, which included the 43rd Infantry Division, one regiment from the 31st Division, and the 112th Cavalry RCT (serving as infantry). This brought the total number of American forces at Aitape to nearly three divisions, collectively called XI Corps, under the command of Maj. Gen. Charles P. Hall.

General Hall’s first step was to encircle the vital Aitape airstrips with a 10-mile, semicircular defensive belt protected with more than 1,000 bunkers and miles of barbed-wire entanglements. Inside this area waited the equivalent of two divisions. But it was a different situation 15 miles to the east along the makeshift American perimeter at the Driniumor, where only three infantry battalions and two cavalry squadrons defended the river’s west bank. This covering force had few barbed-wire defenses and just a few bunkers. With the 20-foot-wide Driniumor only calf deep at the time and thick jungle and towering trees on both sides making it difficult to detect enemy movement on the opposite bank, the exposed Americans nervously awaited an attack.

North Force and South Force Miss the Japanese Force

On the morning of July 10, corps commander Hall, growing impatient for the anticipated Japanese offensive, ordered a reconnaissance in force of the area east of the Driniumor River line. He sent one infantry battalion to the north and a cavalry squadron to the south, leaving only two battalions and one cavalry squadron to defend the American perimeter.

Moving cautiously eastward, the two reconnaissance groups, designated North Force and South Force, inexplicably passed north and south of Adachi’s main assembly areas and failed to detect the presence of the Japanese Eighteenth Army. That night, Adachi launched his attack, which started with a five-minute artillery barrage followed by screaming waves of 10,000 Japanese troops charging across the Driniumor. The assault completely surprised the Americans and overwhelmed their positions. By morning, the enemy had established a sizable bridgehead on the river’s west side and succeeded in isolating the American South Force positioned downstream.

Unable to take advantage of the breakthrough owing to poor communications with his commanders, Adachi missed an opportunity to exploit the bridgehead, which allowed time for the Americans to rush in reinforcements, including 32nd Division artillery, to try and regain their riverside posts. This movement isolated Adachi’s 20th Division, and it would take time for Japanese reserves to attempt a link up and resume the attack.

Fighting For Afua

Days and nights of frustrating and vicious combat followed in the dense New Guinea jungles as pockets of enemy resistance first had to be located and then attacked. With the terrain restricting large-scale troop movements, the hardest fighting invariably fell to infantry squads and platoons, handicapped in their efforts because of the jungle environment, inaccurate maps, the mixing of units, and a lack of information as to enemy strength and positions.

Realizing that another frontal assault on American positions was pointless, Adachi’s last offensive at Aitape was a flanking movement on the southern end of the American line at Afua, a tiny village along the Driniumor. Defense of the area was assigned to the 112th RCT and the 32nd Division’s 127th Regiment, a total of about 5,000 men. Eight companies of the regiment’s 1st and 3rd Battalions protected the northern sector at Afua, 2nd Battalion faced the Driniumor, and the 112th RCT was positioned to the south and west.

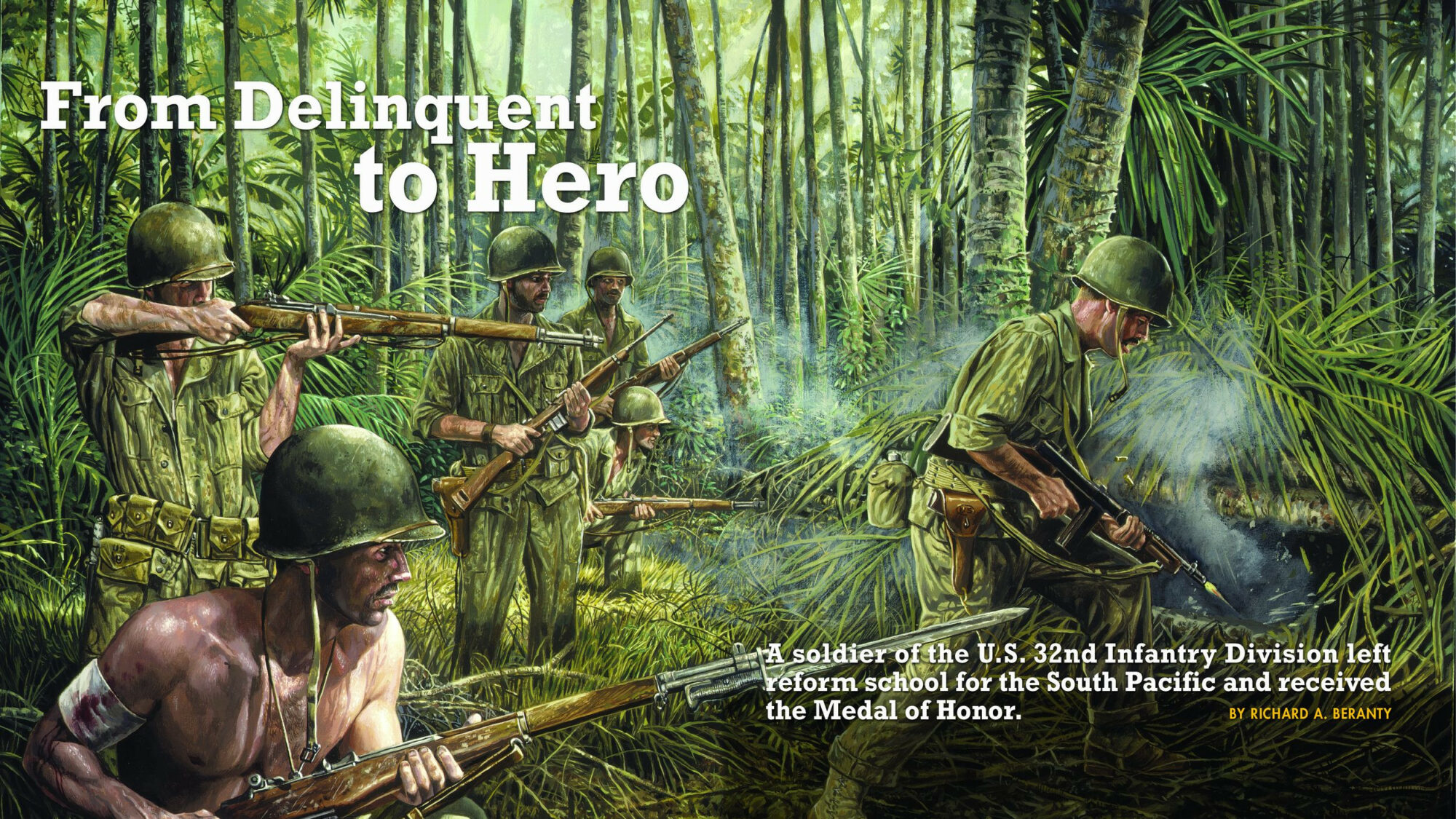

Hastily dug in and with little protection other than what the jungle had to offer, American troops were attacked by Adachi’s men with banzai assaults that bordered on suicidal madness. Several times the village of Afua was lost and recaptured. On July 21, 3rd Battalion’s I Company was ordered out of its perimeter to help check an expected Japanese attack in another area. All but 40 men got out when the enemy closed in with such heavy fire that the platoon became isolated and encircled. That group included Private Lobaugh and Captain Leonard Lowry, I Company commander.

“The platoon organized and fought off the Japs through the night,” explained Captain Lowry of Susanville, California. “The next morning we saw some Japs set up a position about 8 o’clock to the left of a jungle trail which we had spotted as an escape route. The Japs were only about 50 yards away.”

Lobaugh’s Fatal Charge

Pinned down by enemy fire, Lieutenant John S. Kerlizyn of Newark, New Jersey, Lobaugh’s platoon leader, was preparing his men to fight their way out of the encirclement when Lobaugh approached Staff Sergeant Edward L. Jirikowic of Kaukauna, Wisconsin, his squad leader, to make a request.

“When we were ready to go into that heavy fire to knock out the Japs, Private Lobaugh came to me and said that one man could keep them busy enough to allow the rest to break through safely,” said Jirikowic. “He asked permission to try. The fire was extremely heavy and I did not give it. But I did not refuse. Next thing, I saw him crawling alone toward the enemy position.”

The 50-yard distance to the Japanese gun emplacement was devoid of cover. Crawling as close to the enemy position as he deemed necessary, Lobaugh stood and threw a hand grenade toward it, exposing himself in the process. The 20-year-old then rushed the enemy, firing his rifle as he advanced.

“He knew we were threatened with heavy losses,” explained Lobaugh’s platoon leader. “He didn’t falter, even when he was struck repeatedly in his charge on the position. He fired his M1 as he advanced and two Japanese were killed at the enemy machine gun. His action forced the other Japanese to withdraw the gun, and as they attempted this the rest of our unit went ahead and broke through. In the advance of the platoon at least 10 more enemy were killed and others wounded and the platoon did not lose a man, except Private Lobaugh.”

All eyes were fixed on Lobaugh as he made his heroic and fatal charge. “He knew he didn’t stand a chance,” related Private First Class Lloyd East of Trinidad, Colorado. “When he reached grenade-throwing distance he threw one grenade. Just then he was hit, but he got to his feet and charged. I saw him slump a little as he charged, but he kept moving on.”

Recommended For the Medal of Honor

Captain Lowry, as Lobaugh’s commanding officer in the field, recommended that the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest award for valor on the battlefield, be given to the memory of Lobaugh.

“What guts that kid had, what guts,” Lowry said. “When he got part way across that space, Lobaugh raised up and tossed a grenade at the Japs. They opened up on him right away and I know he was hit by that first burst. But instead of turning back, he got up on his feet, held his rifle to his shoulder, and started to rush the Japs firing as he went. Lobaugh was hit and wounded several times but he kept on blasting at those Japs until he got that fatal burst. No, he didn’t knock out the Jap guns. But he made it so darned hot for them that they got the hell out of there and made it possible for the rest of us to fight our way out.”

Lobaugh’s bullet-riddled body was retrieved from the battlefield by his 32nd Division comrades. The official cause of death was determined to be a gunshot wound to the head.

The End of the Aitape Campaign

By August 9, major fighting along the Driniumor River was concluded, and Adachi withdrew his decimated Eighteenth Army to the east, weakly pursued by U.S. forces. Unwilling to risk more lives, Allied commanders were convinced that the campaign to eliminate the Japanese presence in the area was meaningless in regard to the future conduct of the war.

“I visited this battlefield,” wrote General Eichelberger in Our Jungle Road to Tokyo. “General Gill told me the whole story. The XI Corps directed operations, but Gill was the field commander. After Adachi had been repulsed in frontal attacks, he attempted an end run into the Torricelli Mountains. Gill’s force at the right end of the Driniumor Line held the positions against Adachi’s last assault, which took place at a point called Afua. Meanwhile Gill sent a force across the Driniumor which circled into the rear of the attackers. Cub planes—the same Cub planes which would have been so valuable to the 32nd in Buna and Sanananda—directed the movement of this force by flying directly over the troops. Nine days were necessary to move ten miles in the dense jungle. When the Japs failed to break through at Afua and began to retreat, they found four battalions of the encircling force directly across their path. Few of the Japanese survived.”

The Aitape campaign was formally declared terminated on August 25, and the 43rd Division replaced the 32nd in positions along the Driniumor. Total American losses were 440 killed and more than 2,500 wounded. Japanese dead were estimated at 9,300. For nearly a year afterward, General Adachi and his troops continued to hold out against Australian forces in the Wewak area until being forced into the mountains in May 1945.

Maintaining sporadic radio contact with Tokyo, Adachi learned of Japan’s capitulation and finally surrendered to the Australian commander in September with only a few thousand men of his Eighteenth Army alive. Sentenced to life imprisonment by the Australians for war crimes, the Japanese general took his own life in 1947 in a prison compound at Rabaul.

Lobaugh Remembered by His Reform-School Superintendent

Following his heroic actions at Afua, Lobaugh’s body was buried on August 8, 1944, near the battlefield where he met his death in the Aitape area of New Guinea. It was then reinterred at the U.S. Armed Forces Cemetery at Finschhaven, New Guinea, along the east coast of the Huon Peninsula about 50 miles north of Port Moresby, on January 25, 1945. His posthumous Medal of Honor for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity involving risk of life above and beyond the call of duty was authorized one month later on February 26, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and presented to his mother in May.

In a letter dated May 10, 1945, and addressed to Mrs. Ida Lobaugh, Arthur T. Prasse, the reform-school superintendent who had taken the onetime bad boy under his wing, offered these thoughts to the war hero’s mother:

“I do not know whether or not from that day almost a year ago, when you first learned that Donald would not return from the battlefields, until this day you know anything of the circumstances of the details by which he met his fate. But I do know, from your contact and letters to us, that you always had faith in Donald, and knew that he would be a good soldier.

Donald, too, has kept that faith to you and to all of us who had faith in him, and today, almost a year later, his nation is paying him the greatest tribute possible for a soldier to receive.

“Today … I was just reading several letters that I received from Donald while he was in the service, and one written just a few days before he was mortally wounded. He starts out, ‘Dear Dad;’ He always called me that while here at the Republic, and I believe that he thought calling me ‘Dad’ was his assurance that he was going to be the man whom any father would be proud to call ‘son.’”

Buried in Pennsylvania by Fellow Medal of Honor Recipients

In 1949, at the request of his mother, Lobaugh’s remains were returned to Pennsylvania where three holders of the Medal of Honor met his body at the Pittsburgh train station. They were World War II recipients Charles E. “Commando” Kelly and Leonard J. Funk, along with World War I recipient Sterling Morelack. All three served as pallbearers, as did Prasse, the man Lobaugh referred to as “Dad.”

Following funeral services in his hometown of Freeport, the casket was escorted from the church by an honor guard from the Western Pennsylvania Military District and his body reinterred in the family’s plot at Rimersburg Cemetery, Clarion County, about 70 miles northeast of Pittsburgh.

In 2004, a request for Lobaugh’s individual deceased personnel file (IDPF) under the Freedom of Information Act was answered by the U.S. Army’s Human Resources Command in Alexandria, Virginia. Contained in the 62-page document is the official cause of death along with a short list of Lobaugh’s sparse personal effects, which were placed in a cardboard carton and shipped to his mother on March 16, 1945. It included 16 pictures, five letters, one American Legion card, one sewing kit, one fountain pen, and a pamphlet of the school where he had learned the merits of citizenship, dedication to purpose, and hard work: George Junior Republic.

Today, Private Lobaugh’s Medal of Honor is on permanent display in the town library at Freeport, Pennsylvania, a gift from his nephew, Sidney E. Elder. The school that Lobaugh attended celebrates its 100th year of operation in 2009 and is home to approximately 450 troubled youths aged 8 to 18 from one third of the United States.

Well told, thank you and him.

I am the grandson of Rayborn C. Blank a Staff Sergeant in the 127th Infantry of the 32nd Division. I have film footage from the New Guinea campaign of life during WWII on New Guinea. My grandfather was awarded the Silver Star and the Bronze Star in the Battle of Buna Goa. He also took photos and made two scrapbooks of his time in the military. The film footage is silent, however he recorded an audio commentary explaining what’s on screen. I am in the process of digitizing the photos and film. Would you like digital copies?

My dad was in the 32nd at New Guinea, starting at the Buna offensive. I would appreciate you sending me anything you have. So would my family.

Sincerely, Jim

You can search the website for our stories. We have a few on the campaign in New Guinea.