By Richard Rule

By early 1942, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was still unable to boast a single victory in the field against Germany. Under enormous pressure both at home and abroad, he hoped a large-scale cross-channel raid, code-named Operation Jubilee, would send a clear message to the world that England was still very much in the fight.

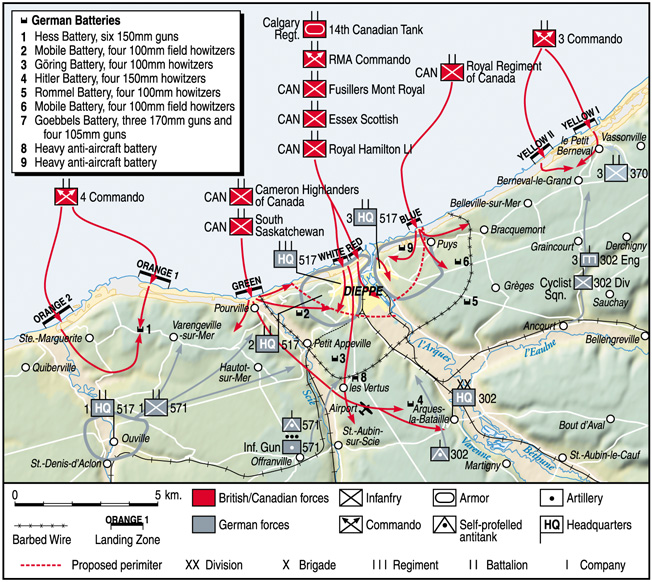

The combined operation, deemed a reconnaissance in force by Churchill, would determine what resistance was likely to be encountered in an attempt to seize an all-weather port by frontal assault. It was a view that fell into line with that of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who had wanted to launch a sizable amphibious landing under fire as a prelude to a much larger operation (Operation Overlord) planned in the years ahead. With the ports of the Pas de Calais considered too heavily defended, the gaze of the interservice planning committee came to rest upon the small French resort town of Dieppe.

The thousand-year-old seaport derived its name from Norman adventurers who found its Diep, or natural inlet, to be an ideal anchorage. The harbor is located in a mile-wide gap at the mouth of the Arques River approximately two miles west of center of an 11-mile strip of coast. Backed by two wide boulevards, villas, and a casino, the open beaches were flanked by two commanding headlands at Berneval to the east and Varengeville in the west, each of which boasted formidable German gun batteries.

It would be a difficult nut to crack because the port, being so close to the English coast, was a vital link in the enemy chain of coastal defenses. The beachfront and cliffs had been fortified with reams of barbed wire and strategically placed strongholds supported in depth by countless machine-gun nests and mortar emplacements bolstered by medium and heavy artillery batteries sighted to cover the beaches and sea approaches.

Combined Operations, under newly appointed chief Lord Louis Mountbatten, finalized the details for Jubilee, which, in reality, had been on the drawing board for some months in one form or another. With available landing craft able to transport approximately 6,000 troops and tanks across the Channel, the bold objective of the raid was to occupy the port of Dieppe, establish a defensive perimeter around the town, inflict as much damage as possible to docks and enemy facilities during the course of a single tide, and then withdraw to England.

The planning, however, was based on the mistaken belief that fewer than 2,000 Germans manned the shore defenses. In fact, close to 6,500 experienced troops of the 302nd Infantry Division were on station with strong mobile reinforcements close by. Instead of outnumbering the defenders three to one, the invaders would be facing the enemy on even terms.

For air cover, the Royal Air Force committed over 70 squadrons to Operation Jubilee, 48 of which were fighters, to form a protective umbrella over the beaches. Opting to forego a softening-up bombardment for fear of alerting the Germans, the RAF would instead provide fighter-bomber support to naval shore parties and ground troops fighting their way off the beaches.

Outnumbering the Germans in the air three to one, the RAF viewed the raid as an opportunity to force the Luftwaffe to do battle on its terms. With all in readiness, it was now a matter of selecting the troops to carry out the operation.

The 2nd Canadian Division had been training in England for nearly three years, but had yet to see combat. The divisional officers were chafing at the bit for operational experience while the restless troops, bored with home duty and frustrated by countless exercises, wanted action. With the men having undertaken extensive training in amphibious assaults, the Canadian High Command insisted that its troops take the lead role in the raid. With the die cast, the eager young men from the Rockies, prairies, and Maritime Provinces of Canada appeared destined to finally get their baptism of fire.

The moonless night of August 18 was the last date in 1942 that offered the conditions of time and tide suitable for the operation. With the new Churchill tanks already embarked onto their landing craft, the assault force of 6,086 officers and men began boarding their ships. Loaded down with full kit and believing they were embarking on another tedious exercise, the grumbling troops filed through the companionways below deck to their assigned areas.

The banter of the men, however, quickly fell silent as unit leaders began distributing maps and aerial photographs in preparation for detailed briefings. As the troops listened intently to their officers, naval crews in numerous harbors along the British coast busied themselves in preparation for putting to sea. Shuffling, shadowy figures moved to and fro along the quays as Aldis lamps flashed signals directing smaller craft to their flotilla positions. In an atmosphere of excitement and high expectation the 252 vessels, under the command of Maj. Gen. J.H. Roberts, slipped away from their English coastal ports to negotiate the 70 miles of seaway to Dieppe.

The various units had been organized into specific groups, each with a clearly defined task that had been studied and rehearsed. Prior to the main assaults, two flanking attacks would see the British No. 4 Commando put the battery near Varengeville out of action, while No. 3 Commando would deal with the batteries at Berneval, thus clearing the way for the five landings.

Scottish Saskatchewan Regiment was Tasked with the Difficult Assignment of Completing Many Objectives, Including Overwhelming the Stronghold at Les Quatres Vents Farm

The Royal Regiment of Canada, along with elements of the Canadian Black Watch, would land on Blue Beach at the small resort village of Puys to secure the east headland at Berneval and capture a gun battery east of Puys. It was imperative that these eastern defenses be silenced ahead of the main landings.

In a simultaneous landing farther west at Pourville, the Scottish Saskatchewan Regiment would disembark on Green Beach. Theirs was a difficult assignment with a number of key objectives. First, they were to offer direct flank support to the landings on the main beaches by clearing the ridge to the east and capturing the radar station sited nearby, then they were to push on ahead and overwhelm the stronghold at Les Quatres Vents Farm, and finally take the battery on the west headland in the rear.

Thirty minutes later, with the beachhead at Pourville secured, the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders would land in a second wave to pass through the Saskatchewans and link up with the main attacking force and its tanks to capture St. Aubin airfield and the headquarters of the German division at Arques la Battaille.

While the Camerons were coming ashore at Pourville, the main effort would see the Essex-Scottish Regiment land in eastern Dieppe at Red Beach and the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry land in western Dieppe on White Beach.

To support the main landings, Churchill tanks of the 14th Canadian Army Tank Battalion would simultaneously undertake the first amphibious tank assault in history. Having been rushed into service despite limited trials and an unreliable reputation, the new Churchills were deemed ideally suited to infantry support and had been waterproofed and fitted with a unique exhaust attachment that would allow them to come ashore from a depth of up to seven feet.

A colorful unit called Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal, made up of French Canadians, would be held in floating reserve. When Dieppe was secured, they would be landed to occupy and maintain an inner perimeter before forming the rear guard covering the final withdrawal through the town to the beaches. To add salt to the German wound, a Royal Marine cutting-out party, acting in the finest traditions of the navy, would dash into the harbor to remove 40 German invasion barges and take them back to England.

Steaming through the inky blackness of the English Channel, the convoy cleared the German minefields and arrived undetected eight miles off the French coast shortly before 0300 hours on the morning of August 19. Holding outside the range of German radar, the escorting destroyers immediately took up their stations east and west of the headquarters ship, HMS Calpe, to act as the eyes and ears of the expedition. Naval personnel aboard the landing ships began to lower the landing craft into the water. It was a noisy, tedious process leaving many convinced the sound must surely have carried to the German shore defenses—but it had not.

The commandos had already departed toward the two headlands as the troops destined for Puys and Pourville were loaded onto their landing craft. As officers moved reassuringly among the soldiers, the men began to blacken their faces and arms; some rechecked equipment, many steadied their nerves with the repetition of orders, while others remained silent, lost in their own thoughts, wondering if they would survive the dawn.

As the LCPs took up station behind the gunboats leading them in, the most hazardous seaborne operation conceived or attempted up that point of the war was underway. There was no turning back.

The run in across the calm, misted waters was unfolding smoothly until some of the landing craft carrying the Royal Regiment of Canada mistakenly formed up behind the wrong gunboat; 20 vital minutes were lost sorting out the confusion. Would they now be able to make it to the beach on time—or even in time to carry out their tasks?

This setback was followed at 3:50 am by the first disaster of the raid, when the gunboat and 23 landing craft carrying No. 3 Commando to Berneval were suddenly illuminated by star shells. Through pure chance, the small Allied force had blundered into a convoy of formidably armed German trawlers and E-boats making for Dieppe harbor. In the brief firefight that ensued, the lead gunboat lost her wireless station and was left a wreck, her guns knocked out and most of her crew wounded.

Many of the small wooden landing craft were sunk or scattered, making it highly unlikely that the commandos’ mission could succeed. Without communications, the gunboat was unable to report what had happened. The flashes of gunfire, however, had been observed from the command ship, leaving General Roberts gravely concerned. He knew that many lives hinged on the commandos successfully silencing the three 8-inch and four 4.2-inch guns of the Berneval battery.

Fortuitously, one of the landing craft, having avoided the engagement, held its course to land three officers and 17 men undetected on the narrow beach of Bellevile-sur-mer. Armed with only their personal weapons and one 2-inch mortar, the commandos scaled the cliff face to engage the Germans. Their harassing fire was so effective that the Berneval guns failed to fire an effective shot during the main landings.

The No. 4 Commando contingent landed without incident on the extreme right flank. In a textbook action, the men blew up the six 6-inch guns of the Varangeville battery and by 0730 hours were on their way back to England. The mission, carried out with daring and skill, would be the only complete success of the entire operation.

By closely coordinating the timing of the flank assaults at Puys and Pourville, the invaders hoped to minimize the chance of alerting the Germans’ main defenses, but the Royal Regiment of Canada was already in trouble. Having not made up the time during the confusion on the run in, the Canadian force had broken into two waves instead of one and would hit the narrow Blue Beach at Puys nearly 20 minutes late and in full daylight. Their protective smoke screen, dispersed prematurely by the breeze, failed to conceal their approach as German gunfire confirmed that the element of surprise had been lost.

With bullets already striking the metal ramps, the tension was almost unbearable as the men steeled their nerves and moved to the forward section of their landing craft ready to disembark. When the LCPs struck the beach, the troops surged forward into a hell few could have ever imagined. Sheltered in trenches and pillboxes, the waiting Germans opened up with a heavy and murderously accurate deluge of fire. The effect was devastating.

The 300 yards from the shoreline to the head of the beach were soon littered with the bodies of the dead and wounded as most of the first wave was annihilated. The few who had cleared the shingle unscathed huddled for dear life against a 12-foot stone sea wall as German shells tore up every square inch of the beach behind them.

While teams tried to blow breaches in the wire, the men beneath the wall found themselves exposed to enfilade fire from a blockhouse overlooking the beach.

The concrete fortification claimed scores of troops as its guns swept the outer face of the wall until an officer, leading from the front, worked his way forward to throw a grenade through the embrasure, killing the occupants, then falling dead himself.

With fire raining down upon them from all angles, the men pinned on the beach frantically signaled the incoming troops to turn back but it was too late. The Germans, now incorporating mortars, let loose a frenzied inferno of explosives and flying shrapnel that cut the next wave to pieces. An officer recalled that within five minutes, “an assaulting battalion on the offensive [had been reduced] to something less than two companies on the defensive, hammered by fire they could not locate.”

With German guns commanding the only access point off the beach, the surviving Royals were trapped. As casualties mounted by the second, and with virtually no radio contact with the headquarters ship, the situation seemed utterly hopeless. Salvation arrived in the form of strafing runs by RAF fighters, supported by naval bombardment that had the German gun crews ducking for cover.

During the lull, the commanding officer, Colonel Douglas E. Catto, desperate to get his men off the beach and onto the high ground, sent Bren gunners to the western edge of the beach to subdue German fortifications on the opposite slope. Showing exemplary leadership, Catto and an NCO then scaled the western edge of the sea wall and began cutting through the wire by hand. Exposed to enemy fire, Catto toiled for over half an hour to clear a path, then rallied his men to follow him through. Only 20 made it before heavy machine-gun fire sealed off the opening.

“From Blue Beach: Is There Any Possible Chance of Getting us Off?”

Finding himself cut off from the battalion, Catto pressed on to the top of the gully, clearing the Germans from a number of houses, but soon found the roads beyond heavily patrolled by enemy troops. The small band, now isolated from the battle, was forced to find cover in the nearby woods where it remained until long after the operation had ended, at which time it surrendered.

A third wave, carrying a detachment of the Canadian Black Watch, landed on the western edge of the beach alongside survivors from preceding waves who lay trapped at the foot of an unscalable cliff. A small group managed to fight its way off the beach to inflict heavy casualties on the Germans, but eventually was forced to surrender when it ran out of ammunition.

With smoke obscuring Dieppe and wireless communications on the beach disrupting signal traffic to the headquarters ship, General Roberts was left unaware of the unfolding tragedy. It was not until much later that the first chilling message from Puys got through, “From Blue Beach: Is there any possible chance of getting us off?”

With over 200 men lying dead along the beach, it was clear that the landing had failed. While a shaken General Roberts belatedly gave the order for evacuation, the prospect of a systematic withdrawal was impossible due to the intense German fire raking the beaches and sea approaches. Barely any of the naval craft that ran the gauntlet made it in and back unscathed. Most were sunk.

In any case, the rescue effort had come too late. Of the more than 700 men who landed, 600 were casualties, including 240 dead. Incredibly, German records examined after the war indicated that the defense of Puys was conducted by only two platoons manning machine-gun nests that incorporated the new rapid fire MG-42s, mortars, and supporting howitzers. This small garrison, which was not reinforced during the entire action, had in less than two hours torn the Royal Canadian Regiment to shreds.

In stark contrast to the disaster at Puys, the simultaneous landing by the South Saskatchewan Regiment on the other side of Dieppe on Green Beach had proceeded unobserved, on schedule but in the wrong place. Instead of disembarking astride the River Scie, the Saskatchewans had landed on the western bank, forcing those units with objectives to the east to detour inland to the only bridge that would get them back over to the right side. With the fully alerted Germans now firing on them from emplacements along the west headland, this costly navigational error had essentially nullified the advantage of an unobserved landing.

One company made solid progress on the west bank, taking all of its objectives on the hills overlooking the village of Pourville, paving the way for the Camerons to land. The other two companies, pushing inland to the radar site, were soon stalled at the bridge, whose approaches were swept by mortars and withering machine-gun fire. Repeated attempts to force a way over to the opposite bank were ruthlessly beaten back with heavy losses.

The battalion’s commanding officer, Colonel C.C.I. Merritt, seeing the roadway to the bridge strewn with bodies, rallied his troops in similar fashion to Napoleon at Arcole. The Canadian officer, however, seized not a flag but his helmet and held it aloft as he walked out onto the western entrance of the bridge, shouting, “You see there’s no danger at all.” His courage injected new momentum into the attack, and the men, following their leader’s example, dashed over the bridge to silence the guns that had cost so many lives.

The troops continued inland, fighting close- quarter engagements all the way, only to find the radar site’s outer defenses too strong to overcome without artillery. The strategic position at Quatre Vents Farm, south of the radar site, was also found to be too heavily defended, and the Canadians were forced to withdraw. It became clear that they could not take either of these objectives; their arduous inland penetrations had been in vain.

Meanwhile, on Green Beach the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders landed at 0530 hours to the skirl of their bagpipes. Their commanding officer was killed as the men dashed across the beach, leaving the unit’s second in command, Major A.T. Law, to take over. Most of the force had landed at the river mouth, and Law, quickly moving the men through Pourville, realized his comrades had not captured the heights of the right bank. Leaving a company to assist the Saskatchewans, he pushed the rest of his command swiftly along the left.

About a mile inland from the coast the Camerons reached the hamlet of Petit Appeville where they crossed over the Scie toward the aerodrome at St. Aubin, but the leading troops came up against exceptionally strong resistance. The tanks and Hamiltons with which Law was to attack the airfield were nowhere in sight; he was not to know that most of them were already dead or wounded.

In any case, the Camerons could not launch the attack alone, so Law decided to strike out toward the fortifications at Quatre Vents Farm. Not long after pushing on, the Camerons found themselves fending off repeated attacks by German units in the area with further reinforcements observed pouring in from all directions. With little knowledge of the enemy dispositions in front of him and no idea how the main landings had fared behind him, Law was in a difficult situation. By mid-morning a message came through for Law to get his men back to Green Beach. At this point, it was clear that the success of the raid was in serious doubt.

The landings by the Saskatchewans and Royals had been made primarily to silence much of the opposition beyond the town and on the flanks prior to the main landings. Despite their valiant attempts, the under-gunned Canadians could not make headway against a well-entrenched and well-prepared enemy. With the German guns still largely intact, the stage was set for tragedy on the main beaches.

Hawker Hurricane fighter-bombers and naval gunfire supported the main effort by the Essex Scottish and Royal Hamiltons coming in to land under cover of smoke. However, the moment the bombardment finished German fire quickly resumed with even greater intensity. Ominously, bullets began sweeping out across the water, slamming into the plywood hulls and metal ramps of the boats. Scarcely reassuring to the nervous troops, this situation was compounded by a navigational error that would delay the tank landings.

Along the Fireswept Beach, All Vestige of Command and Coordination had Been Blown Away, and Enemy Snipers Coolly Picked Off Anyone Showing Leadership

The armor had been an important element of the attack, but without its firepower the men would be left completely unsupported during those first crucial minutes. It was a recipe for disaster. The moment the landing craft dropped their ramps, the troops struggling ashore were greeted by an impenetrable wall of fire.

In the face of such brutal firepower, the organization of the first assault waves completely collapsed as the men vainly struggled to break through the wire entanglements that ranged along the beaches.

The Essex-Scottish landing at Red Beach had no natural cover, and the featureless promenade between the town and the beach was 150 yards wide. They made three attempts to cross this area, but each time they were driven back, sustaining heavy casualties. Along the fireswept beach, all vestige of command and coordination had been blown away, and enemy snipers coolly picked off anyone showing leadership; few company commanders or senior NCOs survived the morning.

The Essex-Scottish Regiment had been nearly destroyed by the weight of fire brought to bear from both the east and west headlands and positions within the fortified villas and houses fronting the promenade. Their attack was maintained only by the initiative of small isolated groups, acting on their own and now fighting for survival. With such grievous losses, any hope of launching a coordinated assault on the town was gone.

On the right, the Royal Hamiltons assaulted White Beach, but once ashore they were raked with impunity from dozens of hidden machine-gun and mortar emplacements. The German gunners could not miss as they capitalized on the skillful use of barbed wire that channeled the Canadians into predetermined killing zones where they were mercilessly mowed down.

With one company completely wiped out, the Hamiltons were reduced to a few desperate bands of men trying, like a punch drunk boxer, to fend off blows they could not see coming. White Beach had become a deathtrap.

The Canadian soldier’s reputation for fearless gallantry had been forged during the nightmare battles of World War I. But like their grandfathers on the Western Front, the men at Dieppe would discover that flesh and blood sustained by raw courage are rarely enough in the face of overwhelming machine- gun, mortar, and artillery fire.

Despite the lack of tank support, some of the Hamiltons breached the wire in several places and made for the shelter of the casino. Forcing their way inside, they overwhelmed the Germans and broke into buildings beyond to establish a defensive foothold. Nearby, a small number of Essex-Scottish troops had also fought their way into Dieppe and set the tobacco factory alight, while others made it as far as the harbor. Their numbers were small and their impact was minimal, but they were at least hitting back in a fight that had been tragically one-sided.

Finally, the tank landing craft made their run into the beaches. As they emerged from the protective curtain of smoke with their ramps down and doors open, German shells began slamming into the metal plating of the landing craft when they were still 200 meters offshore. Of the four troops of tanks landed in the first wave, only 17 made it ashore, with most of these quickly disabled or bellied out and immobilized in the loose gravel. The steep grade of the shingle beaches intermingled with large pebbles and sand made it difficult for the tanks to maneuver, leaving many trapped and floundering under heavy fire.

Major Allen Glenn of the Calgary Tank Regiment recalled, “You couldn’t pick worse terrain for a tracked vehicle. You turn the vehicle a little bit, the stones are rolled into the track, and if you get too many going in at once you break the track.”

The men of the Royal Canadian Engineers, lacking the specialized equipment needed to deal with the beach obstacles, toiled with incredible bravery and suffered horrendous losses as they tried desperately to clear a path for the armor. Of the 314 engineers landed, 186 were killed or wounded.

At the eastern end of the beach, the seawall was found to be only a few feet high, allowing five Churchills to claw their way onto the promenade, immediately drawing substantial fire away from the men on the beaches.

The tanks provided much needed fire support to the small bands of Canadians fighting in Dieppe, but they found themselves hemmed in by concrete roadblocks at the entrances to the town. Left to prowl the beachfront like caged lions, the tanks, all armaments blazing, were a potent force that broke down numerous strongpoints until German reinforcements with antitank guns reclaimed the initiative. The Germans launched coordinated attacks that would eventually bottle up or overwhelm those Canadian forces still fighting within the town, while pushing the rest back to the beach.

While Supermarine Spitfire fighters circled tirelessly above the beaches, Hurricanes continuously came in across the wave tops to strafe and bomb the German positions with unbridled fury.

As the morning wore on, however, it was clear that the main landings at Dieppe had disintegrated. While nothing seemed to be going right for the Allies, very little seemed to be going wrong for the Germans. They appeared to have the situation well in hand. The forlorn body of men on the beachfront, unable to mount a serious challenge to the surrounding German defenses, could do little more than maintain static gunfire exchanges, tend to the wounded, and await death, capture, or evacuation.

Due to faulty communications and heavy casualties among signal groups, General Roberts was still ignorant of the true situation or the magnitude of the losses. Hampered by smoke that completely obscured the beach from view, he tried to coordinate his forces based on fragmented and sometimes misleading radio intercepts.

Believing that the Essex-Scottish and Hamiltons had successfully fought their way into the town and that the Canadians held the western section of the front, he committed his floating reserve, Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal, to reinforce the Essex-Scottish and allow them, with tank support, to push inland.

At 0700 hours, the famous Les Fusiliers Mont-Royals made their way onto Red Beach only to meet appalling fire as soon as they came within range. Further problems arose from tidal influences that spread the landing craft and scattered the men along the beach instead of concentrating them behind the Essex Scottish as planned. The reinforcement was ineffectual, with most of the men quickly seeking refuge beneath the seawall alongside the various units of the Essex-Scottish and Hamiltons. The landing of the Fusiliers ultimately meant that instead of two battalions being trapped on the beach, there were now three.

General Roberts, still oblivious to the real course of events and under the mistaken belief that large raiding parties were moving into Dieppe, decided that the harbor was still a viable objective. Earlier attempts to capture the landing barges had been driven off by German shore defenses, which freed up the Royal Marine A Commando for a new assignment. Landing on White Beach, they were to work their way through Dieppe to launch a flanking attack against German emplacements situated along the east cliffs.

At 0830 hours, the marines began to move toward the beach but were set upon by the most murderous concentration of fire yet seen that dreadful morning. From his landing craft, the Royal Marines’ commanding officer, Lt. Col. J.P. Phillips, could quickly see that the Dieppe beaches were completely blanketed with fire and that attempting to land would be suicide. Standing up in the small forward deck of his craft, exposed to the enemy, he signaled the landing craft following him to turn back. Moments later he was cut down, but not before six vessels veered off, saving 200 men from certain disaster.

With ruthless efficiency, German machine guns, mortars, captured French 75s, and German 88s firing over open sights were tearing the life out of the attack, but it was not until 0900 hours that General Roberts became aware of the full extent of the calamity. With barely any of its objectives having been achieved, Operation Jubilee had collapsed. It was now of the highest priority to save as many troops as possible.

Planning for the original withdrawal had anticipated victory and was to be phased in over a three-hour period. In the shambles of the Dieppe beaches, these elaborate plans had been rendered useless. At approximately 1100 hours, with the distant shoreline a cauldron of smoke and flame, the crews of the landing craft steeled themselves for the run into the beaches. Every craft possessing guns and ammunition joined in close support as destroyers formed a line to follow the rescue.

The Unspeakable Carnage, Terror, and Turmoil at Dieppe Defied Description.

With the last tragic chapter of that terrible morning about to commence, formations of German bombers supported by fighters broke through from the south to add to the misery and chaos. This was the first time the Luftwaffe appeared in force over Dieppe, and Spitfires wasted no time trying to break up the German bomber formations. The sky above the beaches was soon filled with hundreds of aircraft engaged in furious combat.

Along the shallows, meanwhile, landing craft and other rescue vessels were desperately loading as many men as they could while destroyers, guns blazing furiously, continuously streamed up and down the length of the beaches trying to suppress the German fire.

The unspeakable carnage, terror, and turmoil at Dieppe defied description. German guns continued to methodically pound the men without respite. Focke Wulf Fw-190 fighters strafed the crammed open decks of the landing craft, and Luftwaffe bombers from airfields as far away as Belgium and the Netherlands plastered the beaches.

The noise of gunfire, bombs, and shelling was deafening; a man could barely be heard over the frightful din.

Despite the unimaginable horror being played out during those last desperate hours, ordinary soldiers committed deeds of extraordinary heroism and self-sacrifice. Many repeatedly went back and forth through a hail of fire to retrieve wounded comrades; naval personnel held their vessels in close, absorbing incredible punishment as bullets raked many from stem to stern; and Air Rescue launches weaved among the water spouts to pick up downed airmen. On shore, gallant rear guards fought against overwhelming odds, buying time for those on the beaches, while the RAF crew, some on their fourth sortie of the morning, continuously attacked the enemy positions.

With the Germans maneuvering to seal off and secure the entire sector, the tanks on the promenade fell back to form the core of the beach defense. Taking the role of self-propelled guns, they valiantly provided fire support on Red and White beaches until the bitter end, with barely a handful of crewman making it back to England.

Finally, with the likelihood of more casualties than survivors coming off the beaches, further evacuation attempts were abandoned. In the mayhem, many troops, desperate not to be left behind, tried to swim out to the departing craft, but it was too late. Those who remained at Dieppe had no alternative but to surrender.

By early afternoon on August 19, the battered ships were finally homeward bound, leaving behind beaches strewn with burning tanks, destroyed landing craft, and the corpses of nearly 1,000 comrades. A shattered General Roberts dispatched a message to the Headquarters of the 1st Canadian Corps which read, “Very heavy casualties in men and ships. Did everything possible to get men off but in order to get any home had to come to sad decision to abandon remainder. This was joint decision by Force Commanders. Obviously operation completely lacked surprise.”

As a raid, Operation Jubilee had been a dismal failure. The attempt to seize Dieppe had failed on the beaches and surrounding shallows and died. The enemy defenses had been tested, but overall the Germans had not been seriously alarmed. They did, however, undertake a major review of their western coastline defenses and withdraw a number of divisions from the eastern front.

While apparently no one foresaw the tragic consequences of Dieppe at the time, the long-term Allied view was that many valuable lessons had been learned and it was certainly realized that capturing a German-held port by direct assault was nearly impossible. For the D-day landings in 1944, the Allies developed and transported their own artificial harbors, code-named Mulberry.

As vital as this information may have been for the future, there was no escaping the horrendous cost borne by the Canadians and the handful of American Rangers who accompanied them. It was six days before the causalities could be assessed, and in the final count the total military losses amounted to well over 4,000 officers and men killed, wounded, or missing.

Postwar Postmortems Have Generally Accepted That the Dieppe Raid was Too Ambitious, Too Inflexible, and Expected Too Much of the Troops.

Of the seven major Canadian units involved, only one, Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal, returned to England with its commanding officer. Seventy percent of the Canadian raiders did not return at all. The Royal Navy suffered over 550 casualties and lost 34 ships, while the RAF, which had flown nearly 3,000 operational sorties over Dieppe, lost more than 150 aircrew and 106 aircraft, of which 88 were Spitfires.

Three Victoria Crosses were awarded for actions during the Dieppe raid. Captain Pat Porteous of No. 4 Commando, Royal Marines, received the medal for saving an NCO during the raid on Varengeville, and Lt. Col. Merritt received it for his leadership at the bridge over the Scie. The third went to a padre, Captain J.W. Foote, chaplain of the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry, who worked tirelessly and courageously carrying men from the beach to the cover of the landing craft during the evacuation.

What went wrong at Dieppe is a matter of much conjecture, even today. Postwar postmortems have generally accepted that the military plan was too ambitious, too inflexible, and expected too much of the troops. The reliance on tactical surprise over such a wide area was deemed overly optimistic, and the dependence on timing for the various operations left no room for error.

In general, communications were found to be completely inadequate and intelligence was poor, particularly information on the German defenses at the assault points, which was hopelessly inaccurate. In command circles it was believed that the Germans had been warned of the raid by French traitors and were therefore alert and ready.

It should be noted, however, that German reconnaissance aircraft had observed the steady build-up of ships and materiels prior to the operation and that the Wehrmacht was alert to the tidal periods suitable for an amphibious assault just as the British had been. To this end, they routinely maintained a state of readiness during these times and regularly brought up reinforcements. August 19, 1942, fell within one of these periods of heightened alert.

The implication that the nefarious work of French traitors rather than inept planning by the British had led to the disaster at Dieppe has been the topic of debate for decades. However, many believe that the Combined Operations Staff, who had planned and briefed the front-line officers on the raid, should have shouldered much of the responsibility for the failure at Dieppe.

In the end, it was Maj. Gen. Roberts who became the scapegoat. Shifted sideways, he was placed in charge of Canadian reinforcements and would never again command troops in the field.

Cruelly, on August 19 for years afterward, Roberts would receive an anonymous package in the mail containing a small piece of stale cake—a bitter reminder of his comment at the preraid briefing that the Dieppe operation would be a “piece of cake.”

Richard Rule writes from his home in Heathmont, Victoria, Australia. A veteran of the Australian Army, he works in sales management, enjoys fly fishing, and has written several books.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments