By Roscoe C. Blunt

Perhaps the most feared group of accused criminals in the annals of history was a potpourri of personalities who had been associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party. These were the intellectuals; the ramrod-stiff military officers; the cunning politicians; the world’s most vicious, depraved, notorious mass murderers; an architect; a filthy-minded and sex-obsessed anti-Semitic newspaper publisher; a gentle writer of poetry; the bombastic bullies; an unrepentant, ghost-like figure; the subservient military lackeys; and even their self-appointed leader, a bloated, drug-addicted former war hero.

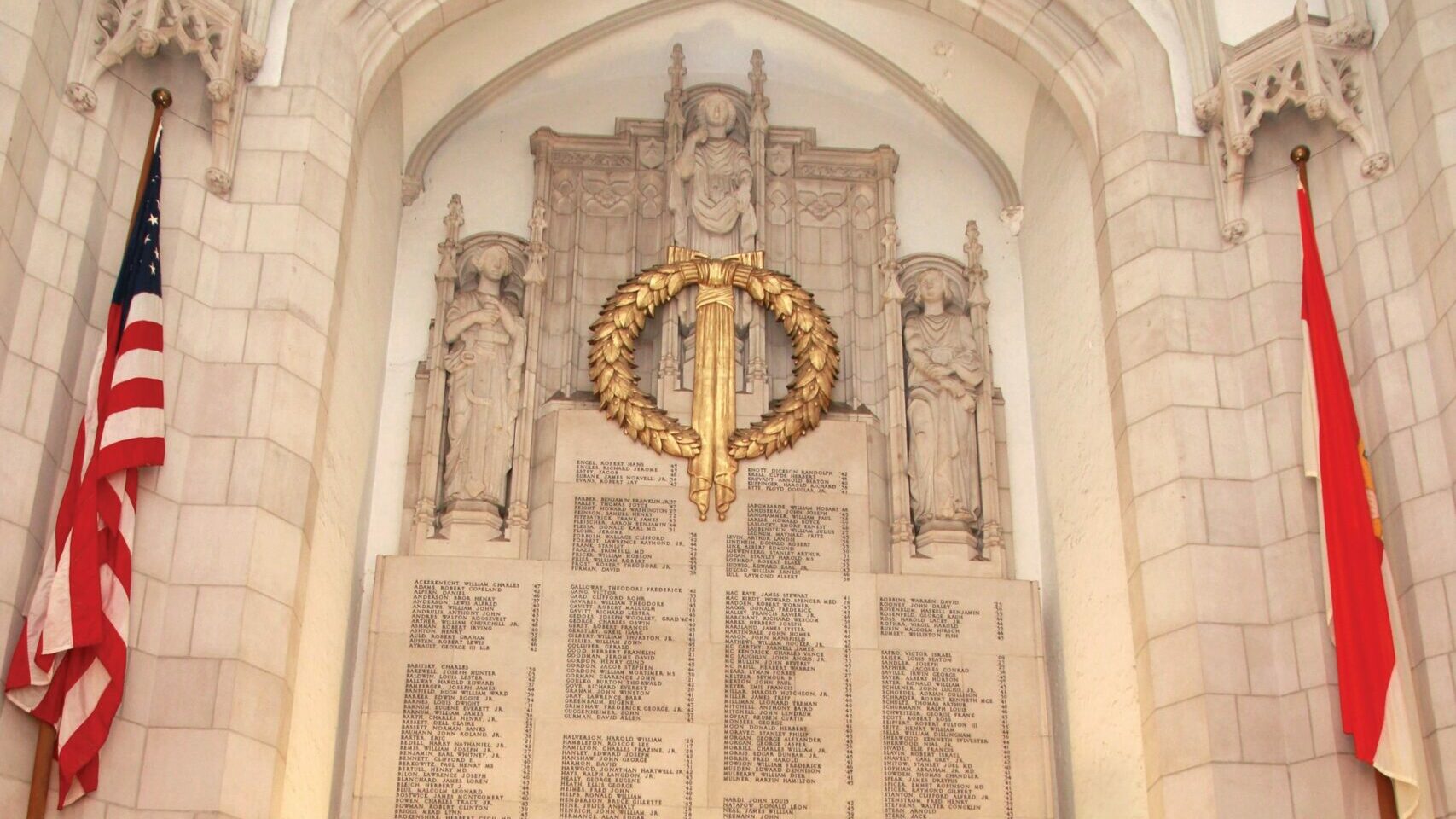

Some were convicted of history’s most barbaric crimes against humanity. Twelve paid with their lives. Seven others, over time, were reduced by lengthy prison sentences to hollow, shuffling shadows of their former selves. All were destined for incarceration, at least during their trials, in two of Germany’s most feared prisons: the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg and Spandau Prison on the western outskirts of Berlin. Three of those accused were acquitted and upon their release soon faded into obscurity. These once powerful leaders of Nazi Germany were the accused of the Nuremberg War Crimes Tribunal.

Sixteen of these captives were guarded by Pfc. Michael R. Prestianni of Framingham, Massachusetts, who later survived months of combat in Korea. During his service in Korea, Prestianni was wounded twice and decorated for valor numerous times. Today, he carries on his World War II and Korean War heritage in various veterans organizations.

Three Months as a Guard at Nuremberg Prison

Upon arriving in the European Theater, Prestianni, a replacement, found himself in the U.S. 1st Infantry Division. His initial assignment was as a guard at the Nuremberg prison. He served in that capacity for three months, bringing him in daily contact with 16 of the 22 accused war criminals.

His remembrance of duty at Nuremberg remains vivid. “At the time, I saw these men only as individual prisoners, guilty of unknown crimes. I had no idea of the magnitude of what they had done. It was only sometime later that I realized in retrospect that I had become part of history,” Prestianni said. “At the time, it was just a job we were told to do. Had I known just who these prisoners were at the time and what they had been accused and convicted of having done, I probably would not have had such a close relationship with them. I would have kept my distance from them.”

Prestianni, the guard contingent, and supervisors under the command of Colonel B.C. Andrus, a strict disciplinarian, were constantly reminded that the prisoners should be treated with civility and objectivity at all times. They were not to be shown disrespect. Before and during the war crimes trial, they were to be considered still innocent, Andrus drummed into the military personnel under his command.

Life in Nuremberg

The Nuremberg prison was a Bastille-like affair. Most of the time the prison was dank, uncomfortably cold, and forbidding, especially during the winter months. Prisoners and guards were forced to wear heavy scarves to ward off the penetrating cold. “It was a very old, ancient, almost primitive prison,” Prestianni recalls. During the dead of winter, cell temperatures constantly hovered near freezing, partially due to severe coal shortages throughout most of Germany, and some prisoners were relegated to wearing stockings as gloves and wrapping their feet in underwear or any other available cloth to keep warm.

For added security outside the prison, three American Sherman tanks, manned by MPs, were positioned at the front, side, and rear entries to the prison. The purpose of the armored reinforcement was to prevent any possibility of attack by groups of still-fanatic Nazis.

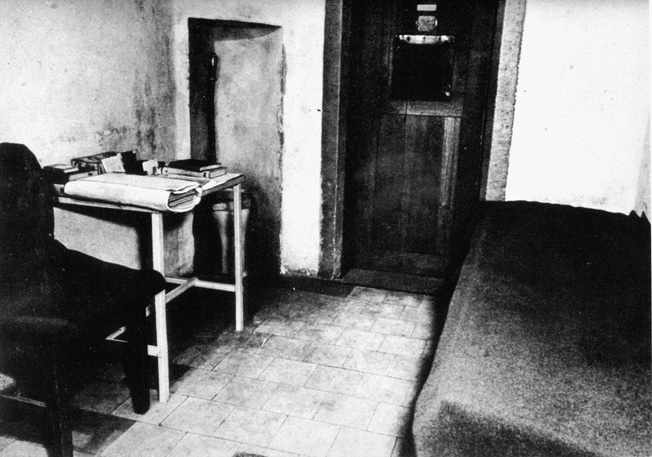

In the prison cellblock, each single-occupant cell had two parallel heating pipes beneath a single, heavily scratched, plastic-covered window, the top half of which could be tilted open for limited ventilation. The prison’s concrete walls, most of which were more than three feet thick, encased the solitary cell window that offered the prisoners no view of the outside world.

Eighteen-inch rectangular holes were cut from the heavy, oaken cell doors, slightly below eye level. Through these openings, aluminum food trays could be placed within reach of the prisoners. The food, prepared in an American-staffed kitchen, offered identical German menus for each prisoner. American chow was prepared for the guards and other Army personnel.

“Generally, I would describe the food, as I recall, quite good,” Prestianni remembers.

Cell doors were never opened when food was distributed. Meals were brought to the prisoners on a precise schedule each day on wheeled, double-tiered push carts by German prisoners from other sections of the prison who were being held for civil crimes. All war crimes prisoners ate from a single German menu. No favoritism was shown nor was a selection offered.

In an attempt to further depersonalize them, prisoners were designated by numbers rather than by their familial surnames. For example, Baldur von Schirach, former head of the Hitler Youth, was known only as Number 1. Number 2 was given to Karl Dönitz, former grand admiral of the German Navy. Number 3 was Konstantin von Neurath, a former high-ranking politician. Number 4 was assigned to Erich Raeder, the Navy’s former grand admiral before being replaced by Dönitz. Number 5 was Albert Speer, Hitler’s personal architect and confidant. Number 6 was Walther Funk, former minister of economics, and Number 7 was Rudolf Hess, once Hitler’s private secretary and deputy führer.

Each prisoner’s cell was equipped with a simple, bench-like bed against one wall adjacent to the cell door, a primitive commode, a wooden table to hold the few allowed pictures and other personal items, and a chair too rickety to support the weight of a standing man. The intentionally weakened table and chair, Prestianni said, prevented possible suicide attempts by hanging. The toilet was the single source of water.

Prisoners Held Under Close Watch

After one of those accused, Robert Ley, former director of the nation’s Labor Front, hanged himself from a drain pipe with a torn towel, prisoners were kept under constant visual surveillance by guards, and while sleeping were forced to do so with their faces and hands exposed above their blankets at all times.

“After Ley hanged himself, this strict suicide watch was instituted,” Prestianni explained. Guards, for the most part, were not allowed to talk to each other or to prisoners while on security duty. Strict attention was always paid to the prisoners. Guards occasionally retaliated against unpopular, troublesome prisoners by rapping on the cell doors with their night sticks to disturb the occupants’ sleep. “This wasn’t authorized, but it was done on occasion,” Prestianni smiled.

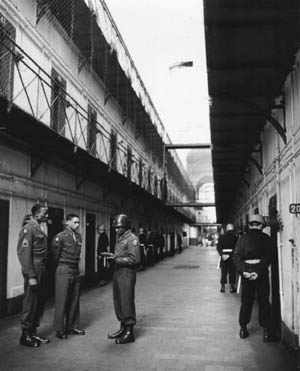

Where the convicted were housed on the ground floor, lower-tier cellblock, the main corridor was 60 meters (195 feet) long, lined by 16 cells on each side, and constantly patrolled by 1st Division guards. To move from one corridor to another, guards carried different colored passes. Movement was extremely restricted and closely monitored, even for the guards. The second-level tier housed high-ranking SS (Schutzstaffel) officers and many of the infamous doctors who had conducted ghastly medical experiments on concentration camp prisoners.

The Female Prisoners of Nuremberg

All female prisoners were segregated on a third tier. “I only patrolled there once. That was enough. We were given strict orders to have no contact whatsoever with these women, no conversation, no nothing and to stay well away from them,” noted Prestianni. “False accusations of rape, abuse, or other misconduct by guards were commonplace. They even accused guards of watching them undress. Whenever these female prisoners, most of whom were former concentration camp guards, created a problem, we merely, as instructed, called the sergeant-of-the-guard to resolve the situation. These women prisoners constantly did anything they could to get a guard in trouble or disciplined.”

The most infamous of the female prisoners during Prestianni’s tour of duty was Ilse Koch, known to guards as the “Bitch of Buchenwald.” With her husband, Karl Koch, the camp commander, Ilse often rode a horse through the camp compound, whipping prisoners. If one inadvertently looked up at her, she arbitrarily ordered the prisoner shot. Koch ordered skin emblazoned with tattoos to be stripped from the cadavers of prisoners and made into lampshades. Her guards were repulsed, and some requested reassignment to another cellblock.

Koch was later tried at Buchenwald and sentenced to life imprisonment. She was released after four years and eventually committed suicide in a Bavarian prison.

Fraternizing With the Prisoners

While on duty, guards carried no weapons, only wooden truncheons. In most respects, fraternization between guards and prisoners was closely monitored by those who set the policies for the prisoners’ confinement. However, fraternization did occur on a regular basis and, for the most part, went unpunished by the prison administration.

Prestianni played checkers and chess with four of the prisoners and argued politics with others. “There was a constant, steady flow of rules and regulations, many of them meaningless, while others tended to be more punitive,” he said. “Each of the governing countries, the United States, England, France, and Russia, had its own interpretation of punishment. With the change of command by rotating countries every month, each of the countries altered the previous country’s rules. The Russians always were a problem and only cooperated with the other countries about 10 percent of the time. They wanted to run the whole show. It was always a battle of authority. However, some Russian guards who had perhaps the best reason to want to harshly punish the former German leaders in retaliation for previous atrocities and other crimes committed in the Soviet Union, were friendly and, even in some cases, considerate of the prisoners and American personnel.”

American guards ate in separate, enlisted mess halls and slept in segregated, barracks-like rooms, six to a room.

Work in the Cellblock

Three days on and three days off with shifts of four hours on, four hours off each day was the standard work assignment for guards. Each watch was of two hours duration, standing almost motionless looking in the cell door openings. Conversation between guards was extremely limited or nonexistent. “The whole focus was on keeping the prisoners under surveillance through the opening in the cell doors,” Prestianni said.

Guards were randomly assigned to prisoners, and the assignments were generally not known by the guards until the duty roster was posted or announced each morning during roll call. During his three-month tour of duty at Nuremberg prison, Prestianni was assigned to 16 different prisoners. “All of those with whom I came in contact spoke flawless English,” he remembered.

Prestianni never served in the trial courtroom, only in the cellblock. On occasion, guards assigned to courtroom duty asked for reassignment as they became emotionally and physically sickened by the film evidence of war crimes that was presented. “There were limits to how much gore that could be tolerated by some of the courtroom guards,” he recalled. “The requested reassignments were generally granted.”

Courtroom MPs wore stylish white MP-emblazoned helmet liners and similarly labeled brassards. All guards were forced to stand practically motionless at parade rest behind their assigned prisoner seated before them in the dock. It was difficult and tiring duty.

Patrolling the Prison Walls

Somewhat regularly, cellblock guards also pulled duty patrolling the parapet-style walls 50 feet above the cellblock and the courtyard, where observation of strolling prisoners below could be maintained. These parapets included watchtowers at the four corners equipped with telephones to contact or summon supervising sergeants or lieutenants, who were constantly on call to resolve problems that might develop. Prompt medical attention was readily available to all prisoners.

“Patrolling the wall was cold, cold, cold,” Prestianni remembered. During watch on one bitter cold night, Prestianni contracted pneumonia and collapsed, unconscious. When he failed to respond to the periodic shouted challenges from the sergeant-of-the-guard, Prestianni was taken to a hospital in Nuremberg where he remained for two weeks before returning to duty.

“Innocent Until Proven Guilty”

Outside the cellblock complex, a small courtyard with a few scraggly pear trees allowed each prisoner the opportunity to walk for 20 minutes each day. The prisoners were restricted to groups of six to eight, which were strictly segregated from one another. Whether the prisoners availed themselves of this privilege was by individual choice.

While they walked, the prisoners were separated by a prescribed number of yards. Generally, due to rivalries and animosity toward each other during their glory years, most adhered to this policy and opted to walk, stand, or sit alone, not engaged in conversations to any degree. Guards were, on occasion, somewhat lenient and allowed some prisoners, based on previous friendships and compatible personalities, to walk in pairs.

During the months of imprisonment, the brisk gait of some of the prisoners gradually evolved into defeatist, head-bowed shuffling as acceptance of their fate gradually wore them down and eroded their will. Some passively resigned themselves to their futures while others fought it off and never fully accepted their fates.

Prestianni said that during his guard duties he tried to adhere to his father’s advice. “They [the prisoners] were to always be considered innocent until proven guilty. I tried to judge them myself, not by what others said of them. I tried to treat each prisoner without rancor.”

Many of the prisoners never accepted the fact that they were no longer on top of the world. In some cases, this arrogance lingered into their years of incarceration. However, one thread of similarity was woven among them. With the possible exception of Speer, none of them could rationalize that they, as individuals, had ever done anything morally wrong for the Fatherland. They, as a group, had no problem with their guilt. They just never admitted to it.

They merely brushed the guilt away with self-serving claims that they were following orders from superiors or perhaps even from Hitler himself in an atmosphere where failure to do so often meant banishment to a concentration camp, Gestapo torture, or even a summary execution. Only Speer stood in the courtroom showing some remorse and, in an act of contrition, admitted his guilt and knowledge of the camps.

Prestianni’s Preferred Prisoners

Did guards favor some prisoners over others? Most certainly. Attitudes toward certain prisoners were determined by the prisoners themselves, their demeanor in captivity, and their personality traits and attitudes toward their American, British, or French guards. Noticeable dislike existed between the prisoners and most of their Soviet guards.

Prestianni particularly liked Speer, Hitler’s architect and the designer of many of Berlin’s most spectacular buildings and later minister of armament and munitions. “He always was respectful, always the consummate gentleman.” Speer was convicted and served 20 years in prison. He was released in 1966. Another favorite was Alfred Jodl, former chief of the operations staff of the Army high command, who was found guilty and executed.

Joachim von Ribbentrop, Nazi Germany’s foreign minister beginning in 1938, was amiable, Prestianni said. Ribbentrop was held in low esteem by others close to Hitler due to his perceived ineptness in many areas. He was the first of 10 hanged on October 16, 1946. “During our conversations, he often asked questions about the United States, a subject in which he appeared to be quite interested,” Prestianni added.

Prestianni also favorably related to Ernst Kaltenbrunner, the notorious chief of Germany’s security police and a behind-the-scenes prime mover at the January 1942 Wannsee Conference where the proposed extermination of Jewry in central Europe was discussed by top Nazis.

The duty roster for guards was revised daily in an attempt to prevent the development of unauthorized relationships with prisoners. Despite this precaution, such limited, semiamicable relationships did exist. Guards gradually learned through everyday observation, however, that the prisoners’ collective makeup truly spanned a psychologically intricate cross-section of those who had served Hitler.

Teasing Schirach

Guards were under strict orders never to respond to verbal abuse by prisoners, no matter how hateful it might be. Prestianni did not recall any such instances.

Besides Speer, Ribbentrop, Kaltenbrunner, and Jodl, Prestianni also guarded Luftwaffe Reichsmarshal Hermann Göring, Grand Admiral Dönitz, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, Reich financier Hjalmar Schacht, Governor of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia Konstantin von Neurath, Nazi philosopher Alfred Rosenberg, virulent anti-Semite Julius Streicher, diplomat Franz von Papen, Minister of the Interior Wilhelm Frick, Grand Admiral Raeder, Hess, and Hans Frank, the governor general of occupied Poland. He has little or no memory of the six remaining defendants, Hitler Youth leader Baldur von Schirach, Labor Front head Robert Ley, Minister of Economics Walther Funk, Plenipotentiary for Labor Deployment Fritz Sauckel, propagandist Hans Fritzsche, or Artur Seys-Inquart, the administrator of the occupied Netherlands.

“One passing recollection I have of Schirach,” said Prestianni, “was teasing him about how much the prison guards were enjoying his former girls and how pretty we considered them. We jokingly told him the girls coveted the gifts American soldiers could offer and they had all forgotten his (Schirach’s) Nazi National Socialism propaganda indoctrination. We needled him by saying his girls wanted to abandon the Fatherland, marry Americans, and emigrate to the United States.”

Schirach, who had been replaced by Hitler as head of the youth movement in 1940 and drafted into Army service where he saw considerable combat on the Eastern Front, maintained his decorum and seldom responded to the teasing.

Hermann Göring’s Suicide

Those incarcerated at the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg were allowed very limited and sporadic visitation rights with lawyers and family members. These visits usually were brief, and participants were separated by a screen. There was no physical contact, and all conversation via microphone was closely monitored by a guard standing behind each prisoner. Gifts, usually clothing, soap, tobacco, and family photos, could be given to prisoners after inspection by a guard.

When asked how the individual personalities, habits, and mannerisms differed, Prestianni responded that they were varied. “Some smiled while others snarled at each other or harshly criticized other individuals. Several were militaristically aloof and looked down upon those they considered to be the mere political element. Still others displayed docile and taciturn mannerisms and personalities. None outwardly felt they had done anything to warrant being in prison.”

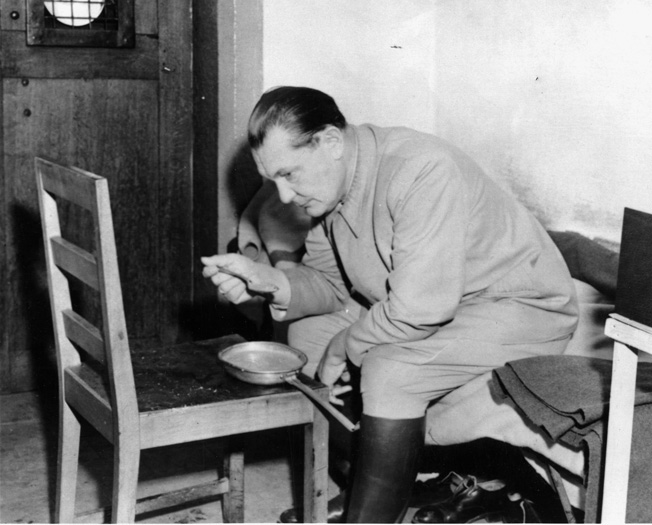

Göring was the acknowledged leader among the prisoners. He had actually tried to usurp Hitler’s authority during the last days of the Reich but remained an ardent supporter of the Nazi regime during the trial, often proving himself a skilled debater.

Göring enjoyed baiting his guards. “How long did it take you to learn what you are doing?” he often asked. When the needling did not abate and became somewhat annoying, Prestianni said he used to give the former World War I ace his own version of a little dig in return.

“At least I’m out here and you are in there,” said the former guard. “

That used to shut him up but usually only for a few minutes, and then he would start up again with the jokes. That was until he took his own life by biting down on a cyanide capsule a few hours before he was scheduled to be hanged.”

Prestianni remembered vividly the night of the executions and Göring’s suicide. “The night Göring pulled that off on October 16, 1946, now that was quite a night,” he recalled. “Colonels from all four countries were running around trying to determine how it happened.”

How Göring obtained the lethal capsule has never been firmly established. The most frequently offered scenario, after intensive investigations, has been that the capsule was retrieved from Göring’s luggage in a storage room and was given to him by an American, Lieutenant Jack “Tex” Wheelis.

The Nuremberg Military Clique

Speer was a favorite of the guards. Considered by some as the most intelligent and talented prisoner, he was the quintessential gentleman. “I could never beat him in checkers. He was good, real sharp,” Prestianni related. “He, like the others, was always bumming cigarettes or cans of Prince Albert tobacco for his pipe. All the prisoners smoked pipes, and they all tried to wheedle cigarettes from us.”

Speer spent much of his time drawing exquisite pencil sketches ranging from landscapes to magnificent buildings to quaint German villages. These sketches were given to guards who requested them and to prison officials. In return, he often was rewarded with cigarettes, pipe tobacco, or other small items he coveted. Today these sketches are highly prized. To maintain the steady flow of Speer pencil sketches, guards always provided him with an adequate supply of paper and sharpened pencils.

Dönitz, who was named successor to Hitler during the waning days of the war and served 10 years in prison, remained aloof. He was quiet by nature and spent much of his time writing his memoirs. By special arrangement with a guard or prison official, he gave his handwritten notes to be mimeographed and returned to him. His daily diary notes culminated in a book after his release. Dönitz remained an unrepentant Nazi until his death in 1980.

Jodl, one of 10 prisoners hanged, was another who never admitted to any personal guilt. “As a good military officer I was only following orders,” he steadfastly maintained with quiet military bearing. He was another of Prestianni’s favorite checker-playing opponents. “He used to tell me he always did what he thought was right for the Fatherland but that just too much came to light during the trial.”

Former field marshal Keitel, another prisoner who was eventually executed, gradually alienated himself from the other prisoners. Some, over time, even grew to despise him. Before his execution, he aligned himself with Jodl and, to a lesser extent, Raeder and Dönitz, the military clique. He could never understand why he had been tried for war crimes. “I did nothing to be here,” he stated.

Neurath and Hess Escaped Execution

Prestianni said of von Neurath, “He looked like the movie version of a Prussian general with his mop of white hair and erect bearing. We used to argue democracy versus dictatorship, the free versus the suppressed. He argued that Germans needed Lebensraum (living space) and that they were looking only for land expansion. I asked him why that necessitated the killing of people to achieve this so-called needed land, especially the people of Poland. During numerous argumentative discussions, Neurath referred to the Polish population and others that were slaughtered by German troops as ‘untermenschen,’ the German expression for inferior beings. These were people, Neurath reasoned, of whom Germany was cleansing the world.”

Neurath, after serving eight years of his 15-year sentence, was spirited away in clandestine fashion, without fanfare, and mysteriously set free in the dead of night on November 6, 1954, because of an alleged eye ailment. He died 21 months later on August 15, 1956.

Hess, former deputy führer of the Nazi party and Hitler’s private secretary during the early years of the National Socialist movement, was sentenced to life imprisonment and served every day of it to the age of 92 when he died in 1987 under mysterious circumstances in Berlin’s Spandau Prison.

Hess was eccentric. “He rarely talked, but when he did his speech was rambling. He was totally indifferent to the world around him and to world affairs. It was eerie. He would just lie on his bed staring at the ceiling with expressionless, sunken eyes and fallow, sort of ashen, death-like skin. He looked like a gaunt corpse, like a ghost. I never heard him speak,” Prestianni remembered.

When Hess exercised or sat on a bench in the courtyard it was always alone, a single, disheveled old man staring at the courtyard bricks. Other prisoners shuffled past him without even glancing in his direction or outwardly acknowledging that he existed. Only Speer occasionally tried to befriend him or penetrate his deep solitude with a few words of encouragement. Other than that, Hess had no social interaction with the other prisoners.

Other prisoners were outspoken in their condemnation of Hess as a traitor to the Fatherland when he flew to England in May 1941, ostensibly to arrange a peace between Hitler’s Germany and Great Britain.

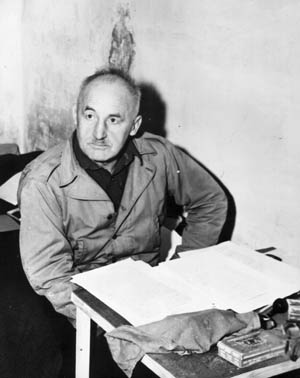

Julius Streicher: “Jew Baiter”

Streicher, sentenced to death, was perhaps the most despised prisoner of all due to his complete obsession with sex. He reportedly carried a whip during liaisons with numerous women. Known as the “Jew Baiter,” even in the United States, he was rabidly anti-Semitic. “He was a true Nazi all the way in every way,” Prestianni recalled. Streicher had published Der Sturmer, a widely read newspaper filled with pornography, ethnic hate, and anti-Jewish cartoons to enflame the German population. Because of his moral corruption, the other prisoners shunned him.

Prestianni guarded Streicher many times. “He didn’t really talk to me very much. He greeted me in the morning and that was about it. He was a physical fitness fanatic who threw his cell window open in mid-winter and splashed toilet water over his bare chest and then did pushups, before meals, after meals, most any time, over and over. He was short but very powerfully built. He was proud of his physique, saying he was strong ‘like Germany.’”

An accomplished horseman, Streicher continued to wear high leather boots and riding britches during his confinement. An avid reader, he availed himself of a well-stocked library with a steady supply of books.

Streicher’s Execution

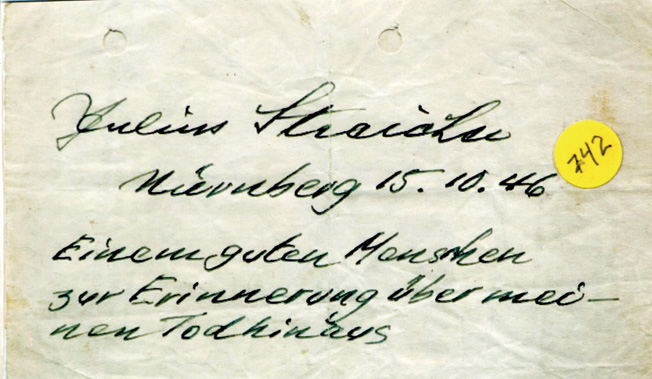

On October 15, 1946, guards and prisoners listened to the pounding of the gallows being constructed. Everyone within hearing distance knew what the hammering signified. One can only imagine the effect the pounding had on the condemned prisoners, now with only one more day to live. On the night he was to be hanged, Streicher gave Prestianni a signed, handwritten note after supper. It was the last thing Streicher was known to have written. The note said, ”To a good man in remembrance of my going forth to death.”

Prestianni said, “I have no idea why he gave it to me. I never treated him differently than I did the others I guarded.”

Prestianni and another guard handcuffed Streicher and walked him silently to the gallows chamber, where they rapped on the door with their truncheons. The door was opened just enough to allow Streicher to enter. Again, without a word being spoken, the door was slammed shut. The same routine was followed for each of the condemned prisoners. Streicher, for reasons never made known, was photographed clothed and then naked and again in death.

An anti-Semite to the end, and proclaiming that his death was a victory for world Jewry, Streicher’s final shouted words as he dropped through the trap door to his death were, “This is the Purim Festival for 1946. Long live Germany.”

Asked whether the 60-year myth about Streicher struggling for 20 minutes at the end of the hangman’s rope was true, Prestianni said guards never witnessed the hanging and he had not heard any such rumors at the time, but guessed it could have happened. “He was physically one tough guy,” Prestianni offered.

Ribbentrop Was “An Excellent Checkers Player”

Hans Frank, known as the “Slayer of Poles,” was small, outwardly arrogant, and had a cruel face, Prestianni revealed. “He never repented for anything he ever did. Bragging of his ability to mass murder millions of Jews, Frank never admitted to his brutal inhumanity during the war crimes trial but was sentenced nonetheless to hang. He remained bombastic and arrogant right up to the end, all the while looking upon the other prisoners as inferior beings.”

Ribbentrop, another of Prestianni’s checker opponents, was vainglorious, almost constantly given to pompous bragging and considered stupid by the other prisoners. Ribbentrop, Prestianni related, was a man without humor. “But, he gave us no problem and I found him engaging to talk to and an excellent checkers player.”

Raeder was sentenced to life imprisonment but was released for poor health on September 26, 1955. He maintained an air of superiority toward Dönitz, considering him still a subordinate officer.

Raeder kept to himself, voraciously reading and writing his memoirs, but when he interacted with the others, it was often to lash out in anger. Prestianni does not recall Raeder maintaining even a limited friendship with the other prisoners. “He was strictly military during the three months I observed him. He was usually confrontational and argumentative with the other prisoners. He considered himself the senior member of the prison military fraternity.”

Innocent at Nuremberg

Former president of the Reichsbank Hjalmar Schacht was one of three war crimes defendants who were found innocent of all charges against them. “I never really got to know him very well during the few months before he was released,” commented Prestianni, “but at one time he tried to teach me an intricate German card game, but I never could catch on to it. I don’t remember the name of the game after all these years. I do remember that Schacht, like most of the others, steadfastly maintained his innocence, never admitting to guilt in any form. He argued that he was being persecuted.”

Schacht had been imprisoned in July 1944, under suspicion of being part of an assassination conspiracy against Hitler. After his release from prison in Nuremberg, a Stuttgart court sentenced him to eight years in a work camp. After two years he was released and promptly reestablished himself in a successful career as a financial consultant for developing nations.

The Imprisoned Architects of the Third Reich

Alfred Rosenberg was considered by Hitler the philosopher of National Socialism. Convicted and hanged, Rosenberg’s ideology led to an appointment as minister of the occupied eastern territories in 1941. It was an appointment that, when coupled with his Baltic origin, brought him into sharp conflict with most of those in Hitler’s entourage. To some, he was demeaned as “the foreigner.”

“I didn’t like his looks at all. His face had an animal look to it,” Prestianni stated. “He often went for hours without speaking to anyone. And when he spoke, it was to lash out violently at anyone close to him at the time, even the guards.”

Kaltenbrunner had perpetrated extreme barbarism in the extermination of Jews through the planning and execution of the Final Solution. While he was held at Nuremberg, he portrayed himself in a quiet, unassuming demeanor.

“He was a rather low key person at Nuremberg who caused the guards no problems at all,” said Prestianni. “I rather liked him for the way he acted toward us. I played checkers with him on a number of occasions,” Prestianni revealed. “When I once asked him why he had done what he was convicted of doing, he replied that he only did what the Fatherland [Germany] instructed him to do. By creating an Aryan nation, the world would look up to and envy Germany for its racial purity.”

Frick, one of Hitler’s closest advisers during the early years of the Nazi regime, was one of those hanged. He had been instrumental in establishing a totalitarian state. Designated as protector of Bohemia and Moravia in August 1943, he played a major role in developing the concentration- and labor-camp network for the slaughter of millions.

“Frick was rather taciturn, not given to talking. He was not tall at all and didn’t really stand out in any way from the others,” Prestianni said.

Franz von Papen helped pave the way for Hitler’s ascension to power in 1933. Throughout the trial, he steadfastly maintained his innocence, saying they had arrested and charged the wrong person. He was found innocent and released but sentenced in 1949 by a German court to nine years in prison.

“He was a man of some stature with flowing white hair, but he would still never be noticed much in a crowd. He was largely overlooked in prison,” Prestianni said of von Papen.

Sent to Spandau

Without fanfare or advance warning, on July 18, 1947, the remaining prisoners at Nuremberg were told to assemble their meager belongings. They were individually handcuffed to guards, driven by ambulance to a nearby airfield, and flown to Berlin, where they were processed at Spandau Prison.

Prestianni’s assignment was over, and he was transferred to guard duty at a POW compound at Bamberg, Germany. After being rotated home in 1949, he reenlisted and soon found himself on Okinawa prior to deployment to Korea. He still resides in Framingham after retiring from a 33-year career in supervisory positions with the U.S. Postal Service.

My father Ed Rossi was also a guard at the Nuremberg trials. He guarded the prisoners in their cells and also stood guard in the court room. He just celebrated his 93 birthday, and is smart and caring as he has always been.

My father Paul Davis Smith served at a guard at Nuremberg though he never really talked much about it so I don’t know in what capacity. I sure would like to find out more about his service.

My dad, Frederick M. Bencriscutto, was in the field artillery in the 1st Infantry Division during WWII. At the war’s end, he was assigned to the guard detail at Nuremburg. He held the rank of seargent when he was discharged in 1945.

I would like any information that would lead me to a more detailed understanding of what my father did while part of this undertaking.

My father Gordon Fitzgerald also spent several months as a guard there. He told multiple stories of his time there. Came back to the States in Jun 46.

Wonder if anyone remembers him?

My father was a guard in the courtroom (Palace of Justice) at the Nuremberg trials in 1946. His name was Raymond J Arsenault. He recently passed in January of 2020 at the age of 91. He would have been 92 the following month.

I do have a photo of my Dad standing behind the German prisoners. There was a large clock on the wall that was above his right shoulder. Of course he was amongst other guards to his left and right.

I wish I would have ask more questions about his experience there.

My dad was a guard at the trials he had a Picture of himself standing behind the prisoners he died at 86 in 2015 the picture is gone and he never wanted to talk about he was a sgt and received a purple heart.

My father became an MP after the war. He was sent to Nuremburg and stood guard at the Judge’s quarters. He said that he had the pleasure of meeting the judge known as the Hanging Judge.

My mother’s cousin was a WAC serving in England during WW2. After the war, she and other WACS were asked to stay for the Nuremburg trials to serve as stenographers . They were told they would be part of history. They were put under guard at a hotel and taken to court with armed MPs to trial each day. They saw the horrible films the NAZIs took and heard the case the prosecution presented with all the evidence and saw the brutal photos, It was very hard on these young women, but they did their job they were asked to do. She kept a scrapbook which had photos of her group and many signatures of court officials and army officers commending them for their service. Her last name was Marsico (can’t recall her first name} and she was from Montgomery, WV. I believe her rank was a corporal.

my father david c bergeron was a 1st LT with the guards at the war trials. we went to Germany with and my younger brother was born there, dad remained un the Army until 1960, when he retired after 32 years service

My father was also a guard, but he said he always was on the outside guarding. He did mention seeing the prisoners in their cells. He was made an MP after the war – William A Shoemaker from North Carolina. He died about five years ago and I wished I would have asked questions. I’m always looking for pictures of the guards and hoping one day I will see him as a young soldier.

My father, Jack J. Wells, was military policeman and a Provost Sergeant in charge of a special confinement unit whose responsibilities included providing security for the war crimes trials in Nürnberg. I have a brass pot, called an aspersorium, obtained by my father. This brass pot held the holy water that an attending priest sprinkled on the condemned immediately before their execution. The priest was most likely the Nürnberg prison’s Lutheran chaplain, Henry F. Gerecke. In addition to this brass pot I have three skeleton keys to the cells that held the Nazi war criminals, as well as a pair of wooden spoons used by them. One spoon has a carving of a skeleton key on its handle, the other an engraving of “N 19 P.” I could never determine the significance of the latter carving.

My father was an MP at The Nuremberg Trails. He was the popular picture court room scene the second on the left of the door. There was also a picture of him guarding Hitler. He was able to get to get the Hitler people’s autographs. I inherited all of it. His name was David C. Porter from Pennsylvania

My Dad was a guard at the Nuremberg trials. He guarded Goehring. Goehring gave my Dad a notebook that he had drawn in. It was in my family until the early 2000’s. My Dad was murdered, hanged, when I was 5 years old in 1965. My mother gave the journal to my oldest brother who died in 1998. It was supposed to pass to me, but my ‘brother’s widow lost it and it has not been turned over to me. I have searched photos of the trials to see if I could find my dad. My mother had pointed his photo out to me on several occasions but I was too young to remember. All I can recall is that he was standing to the left in the court room. Because of the tragic manner in which my father died, we did not often speak of the trials. They had a profound affect on my dad, who always said, “I would never want to be killed by hanging.” Yet, the constables who allegedly murdered my Dad did just that. I have been searching for evidence that my Dad was a guard, so that the stories I have been told since I was a child could be documented. If anyone knows how I can verify that he was a guard, please let me know. It would be so greatly appreciated.

Hi Susan,

Give me information about your Dad and I will help you research about your father’s deployment to Germany.

I need your:

Dad’s birthday.

Your Mom’s birthday and maiden name.

Where they lived.

If he is American it will be easier to find some kind of information about him. You can contact me via email at [email protected]. I look forward to hearing from him.

Regards,

Rebecca Leuchter

My Dad Arthur Tacopino was a guard at The Nuremberg Trials. He is in several pictures standing at Hans Frank’s left. Boy I wish I asked more questions of the trials.

My father, Kenneth Gurall, was in the 26th Regiment, 1st Infantry division that also was sent as a reinforcement in Europe in April 1945. (His enlistment date was February 5, 1943 from San Francisco.) He served as a guard in Nuremberg. His parents received a letter and photo of him guarding outside at the entrance. I have only found it in a digital newspaper article and the photograph is not clear. Does anyone know of him. I really appreciate this detailed article. I would love to be able to find more information about his service there and any more details of his WW2 experience.Thank you!