By Glenn Barnett

War clouds gathered rapidly once Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. Allied demands that Hitler withdraw his armies went unheeded. On September 3, Great Britain reluctantly declared war. Berlin then issued orders to all U-boats to begin hostile action against English shipping. Passenger liners were not to be touched.

Meanwhile, in Liverpool passengers boarded the liner SS Athenia for passage to North America. The unescorted liner tried her best not to be a target by zigzagging and running with her lights out.

However, through the periscope of U-30, Athenia looked every bit like an armed merchantman and therefore fair game. On the first day of the war, the Athenia was torpedoed and sunk. Her 1,103 passengers, including 300 Americans, clung to life rafts and debris until help arrived. One hundred and twelve would die that day.

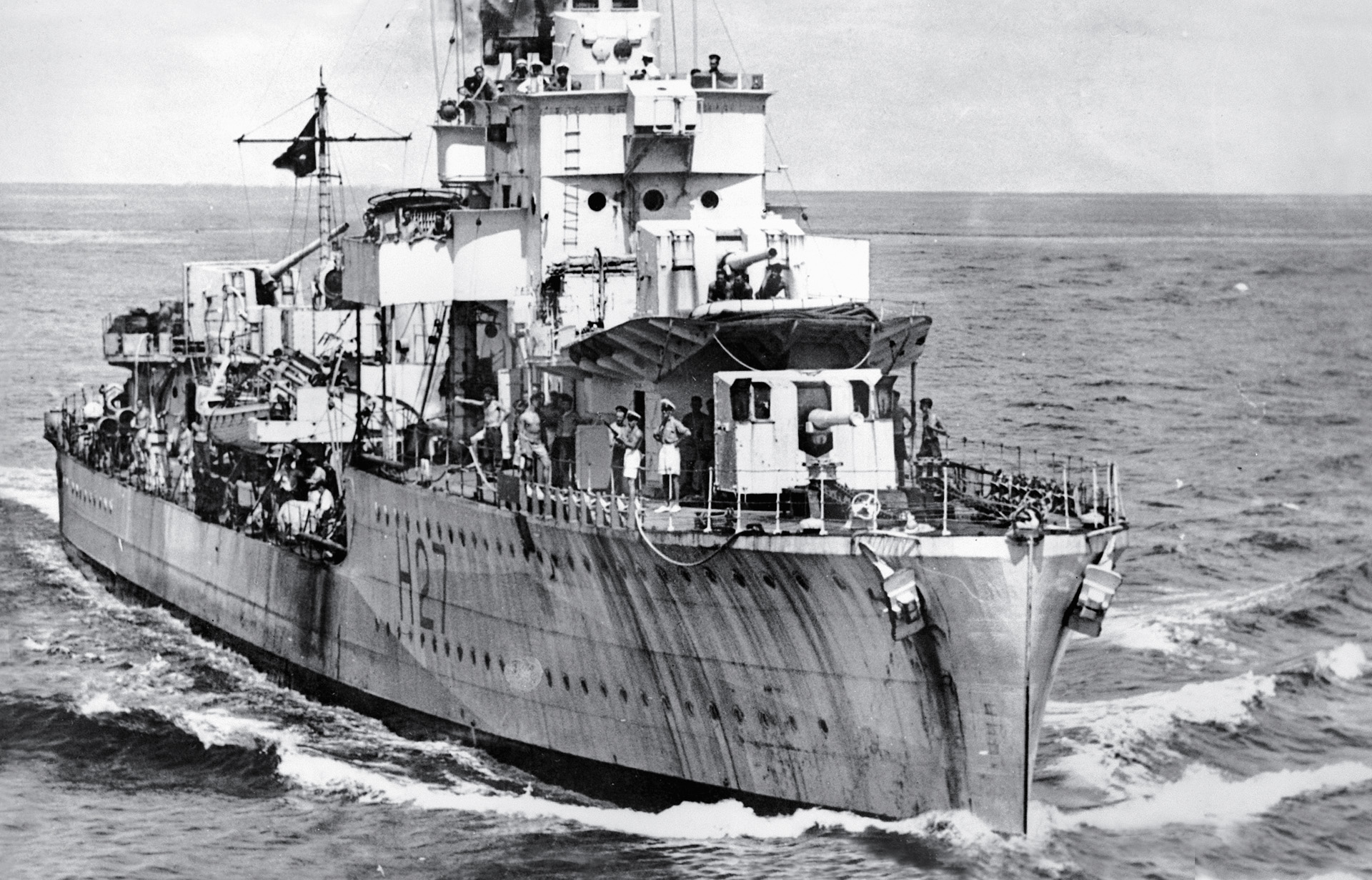

Among the five ships that responded to Athenia’s distress signal was the destroyer HMS Electra (H27). While keeping a wary eye out for submarines, the rescuers combed the water for survivors. Back ashore, Joseph P. Kennedy, the U.S. ambassador to Great Britain, dispatched his 22-year-old son John F. Kennedy to meet with the American survivors.

Obsolete Before She Launched

For Electra, it was the first but not the last time she would pluck survivors from the sea. She was one of nine E class destroyers laid down in the mid-1930s. Fast at 35 knots, she weighed in at 1,369 tons and was designed to carry four 4.7-inch guns and eight torpedo tubes (four to a side). Depth charge launchers completed her offensive capability. Her standard complement was about 170 men.

Like so many modern weapons, Electra was obsolete before she was launched. New destroyer designs in Germany, Italy, France, and Japan were placing emphasis on larger, more heavily armed destroyers. Like most other surface ships of her day, she was woefully inadequate in anti-aircraft capability.

When World War II started, Great Britain would have 113 modern and some 60 outdated destroyers with 24 more under construction. She would need all of them and every ship she could build or borrow from the United States. During the war she would lose 139 destroyers, including Electra.

Electra was designed for fleet protection and convoy escort duty. After the rescue of Athenia’s passengers, she was very busy with convoy protection duties for the remainder of the “sitzkrieg” or “phony war” in Europe. Electra could boast that no merchant ship she was assigned to protect was ever sunk by the enemy. She soon earned the nickname “Lucky ‘lectra.”

The German invasion of Norway in the spring of 1940 took Electra to Arctic waters. She was one of the first warships in the area escorting troopships trying to hold back the Nazi tide. It was here that she registered her first kill. Her gun crews heard the roar of a German bomber and sighted it coming through the gray mist before she herself was seen. Her first shot sheared off part of the German’s wing, and the plane was seen falling fast behind the fog-shrouded mountains.

When the battlecruiser HMS Warspite made her famous run into Narvik to deal with nine stranded German destroyers, Electra was to have preceded her as a minesweeper. But the admiral in charge did not want to waste time fishing for mines. He stormed ahead into the fjord, leaving Electra behind to hold the door and keep watch at sea. Her crew was deeply disappointed as her sister destroyers bagged the lot of the Germans.

While still in Norwegian waters, Electra and other destroyers provided a screen for the aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal as she launched planes against German positions. While recovering her planes, the carrier steamed into a dense fog bank. Not all the destroyers got the message to alter course, and Electra slammed into the side of her sister ship Antelope. Her bow nearly torn away, Electra limped homeward for repairs.

The Hunt for the Bismark

In May 1941, Electra and three other destroyers were patrolling with the battlecruiser HMS Hood and the brand new battleship HMS Prince of Wales. The Admiralty had intelligence that the German battleship Bismarck had put to sea. The little British battle group, steaming south of Iceland, received word that the Bismarck was sighted to the west along the calm waters at the edge of the Greenland icepack. The Hood and her escorts immediately set a course to intercept the German raider.

All concerned thought the venerable Hood was a good choice to go up against Bismarck. She was the largest warship in the world at the time, weighing 42,000 tons and boasting eight 15-inch guns. Bismarck was officially 35,000 tons, but unknown to the British, she was secretly built to be the equal of Hood in tonnage. She, too, had eight 15-inch guns.

The battlecruiser, battleship, and four destroyers steamed westward into the night. At 3:30 am on May 24, 1941, Electra’s captain, Commander Cecil Wakeford May, ordered the crew to action stations. He told his men to expect contact with the enemy at 6:00 am It was a cold, wet watch.

Seas were heavy and the weather foul as the British searched the gloom for the elusive enemy. Lookouts high above the deck scanned the horizon for any sign of danger. Primitive ship radar could not yet see over the horizon.

Hood and Prince of Wales were easily capable of the 28-knot cruising speed they were making through heavy seas. However, the escorting destroyers were taking brutal punishment at this speed. Electra’s boats were smashed, and funnels were ripped and dangling from their base. Admiral Lancelot Holland, commanding the flotilla aboard Hood, allowed the destroyers to slacken their pace as the two capital ships drove on. Electra found a more comfortable speed riding over the waves rather than through them. She watched as Hood and Prince of Wales steamed out of sight into the frigid dawn.

Soon Electra received a radio message from Hood, “Enemy in sight, am engaging.” On deck, lookouts thought they heard the distant muffled guns of battle. In no more than 10 minutes, Prince of Wales sent another message. “Hood sunk!”

When he heard it, Gunnery Officer T.J. Cain rounded on the signalman and cursed him for his sick joke. “My God, sir, but it’s true, sir.” The man was in tears.

A Fruitless Search for Survivors from HMS Hood

Gossip travels fast aboard ship. Even before the official announcement from the bridge, all hands knew of the disaster. The crew knew what to do. They had picked up some of the 900 survivors of Athenia and now prepared to do it again. Hood had a complement of 1,400 men. Hundreds of wet, exhausted, and shivering sailors were expected to clamor aboard. Hot beverages and warm food were prepared. Blankets and life preservers were brought up, medical supplies and hammocks made ready. Officers prepared to abandon their cabins to make way for the injured. Since the ship’s boats were smashed from the high-speed chase, scrambling nets were put over the side.

Intermittent sleet and rain on the cold and mournful morning reduced visibility, but Electra soon broke out of the mist and into the clear to find herself amidst the wreckage of Hood. All hands were horrified by what they saw. There was an enormous amount of flotsam and jetsam on the surface of the sea, but no survivors could be seen.

“Good Lord,” exclaimed one sailor, “she’s gone with all hands.”

Electra pushed slowly through the mass of floating debris, desperately searching for anyone. A shout went up as a man was sighted clinging to wreckage. Then two more were spotted. Crewmen scrambled down the rope ladders, wet to their knees, to fetch the only three survivors. They were wrapped in blankets and sent below to the ship’s doctor.

Electra continued her search for hours but only those three men of Hood’s 1,400 were ever found. A solemn silence settled in on Electra’s crew as she rushed her precious human cargo to a hospital in Iceland. Soon Prince of Wales came into sight. Low on fuel, she had given up the chase after Bismarck. She had taken five hits on her superstructure and looked badly beaten up. Yet, Bismarck’s reputation as a super ship would last only three days more.

Electra accompanied Prince of Wales back to England; they would sail together again. While the new battleship underwent repairs, Electra went into port to receive a new Oerlikon anti-aircraft gun. Half of her torpedo tubes were removed to make room for the new armament.

First Escort to Russia

In July 1941, the destroyer was ordered to escort the first convoy to Russia. England’s new ally needed every type of help as the Germans slashed through the Ukrainian countryside. No love was lost between the Soviets and the British, but as Prime Minister Winston Churchill quipped, “Even if Hitler marched into hell, I would put in a good word for the “Devil in the House of Commons.”

The North Atlantic had been cold but was nothing compared to the Arctic. With one other destroyer, the Anthony, a veteran of Dunkirk, and a handful of minesweepers and trawlers, Electra set out with her charge of 13 merchant ships. Fortunately, the Germans were not yet aware of the Murmansk convoys, and the little flotilla made it safely to Archangel. Future convoys would endure the full fury of Nazi displeasure, but the first trip was uneventful.

So was Electra’s stay in the Russian port of Archangel. She was there until September, but only once was her crew granted shore leave by their communist hosts. When the crew was finally allowed ashore, they met sullen people, careworn and distrustful in the paranoid people’s paradise. When back aboard, the crew did not feel they needed further shore leave. When Russian liaison officers came aboard, however, the vodka flowed freely.

At long last, the Russians were able to scratch together a convoy of merchantmen for Electra to escort back to England. She was eager to leave as the ice was beginning to block the northern passage. “Lucky ‘lectra” arrived home safely once more.

After an Overhaul, Off to the Pacific

Electra was due for an overhaul, and for six weeks her crew enjoyed liberty and a surcease of ship’s duties. Civilian union rules prohibited sailors from lifting a finger to work on their own boat. The crew was not at all put out and soon found themselves made welcome in the homes of the workmen.

When at last the destroyer was ready to sail in late October, she was once again teamed with Prince of Wales. Admiral Tom Phillips aboard Prince of Wales was ordered to Singapore to “show the flag” in the Pacific Ocean. The long cruise took the ships around the tip of South Africa, and for the 173 men aboard Electra the voyage in warm weather and calm seas was like a vacation after their North Atlantic and Arctic duties.

As the little flotilla neared Ceylon in the Indian Ocean the crew became uneasy. The Japanese were making hostile threats in the Far East, and it finally dawned on everyone that they had been sent to meet that threat.

In Ceylon, they met up with the battlecruiser Repulse. Meanwhile, Phillips had flown ahead the Philippines to meet with his American counterparts, General Douglas MacArthur and Admiral Thomas Hart. He hoped that the British and the American Asiatic Fleet could combine in the event of Japanese aggression. Isolationist sentiment in the United States was still strong, and no promises could be made.

Force Z Gets Surprised by the Japanese

Steaming in concert with Prince of Wales and Repulse, Electra was one of four destroyers in escort as the island of Ceylon faded in the distance. Officially known as Force Z, their destination was Singapore.

Some sailors aboard were soon to notice that the combination of the battleship, a battlecruiser, and four destroyers was the same as that which had hunted the Bismarck with disastrous results. Sailors are superstitious, and the similarity of their present force was a matter of discussion below decks.

The little flotilla arrived in Singapore on December 2, 1941. They were too little and too late. It had been planned that an aircraft carrier accompany them to provide air cover, but the designated ship, HMS Indomitable, had run aground during training in Jamaica and had to be docked. The light carrier Hermes was already in the Indian Ocean (and would later be sunk by the Japanese), but was never ordered to join up with Force Z.

Within a week, there was no time for any such considerations. Simultaneously with their attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese struck southward from bases they had occupied in French Indochina (Vietnam). When Japanese troop transports were reported heading toward the Malay Peninsula, Phillips knew that he had to act. He pleaded for air support from the antiquated planes stationed in Malaya, but like elsewhere in the Pacific, the Japanese had struck hard at Allied airbases and the air arm could not promise anything. Nonetheless Force Z put to sea.

It was a common mistake at this time for Westerners to hold Japanese military capability in contempt. It was believed that the Asians could not conduct complicated fleet actions, that their air power was inferior, and that the whole Japanese race was somehow myopic. Force Z would soon find out that this was an enemy not to be underestimated.

Admiral Phillips’ plan was to sail well out to sea and wait for the cover of darkness to rush toward the beaches where the enemy transports were reportedly sighted. When dawn broke, there were no Japanese vessels in sight, but Force Z was spotted by Japanese patrol planes.

After checking on another false rumor of Japanese landings, the flotilla headed back out to sea beyond the range that enemy torpedo bombers were thought to reach.

Now the Royal Navy would learn the cruel truth about its new adversary. Unknown to British intelligence, Japanese torpedo planes had a much longer range, and worse, the Japanese long lance torpedo, the best in the world, had a longer range than its British, American, or even German counterparts.

When the first planes were spotted, Commander May instinctively rushed Electra between them and Repulse. A cacophony of shot and shell from her Oerlikon brought down a torpedo plane and unnerved his wingman into launching his torpedo into empty ocean. Cheers went up all over the destroyer’s deck, but they were premature. Enemy planes swarmed in to bomb, strafe and torpedo the ships below them.

Once Again, Electra is Called on to Pick Up Survivors

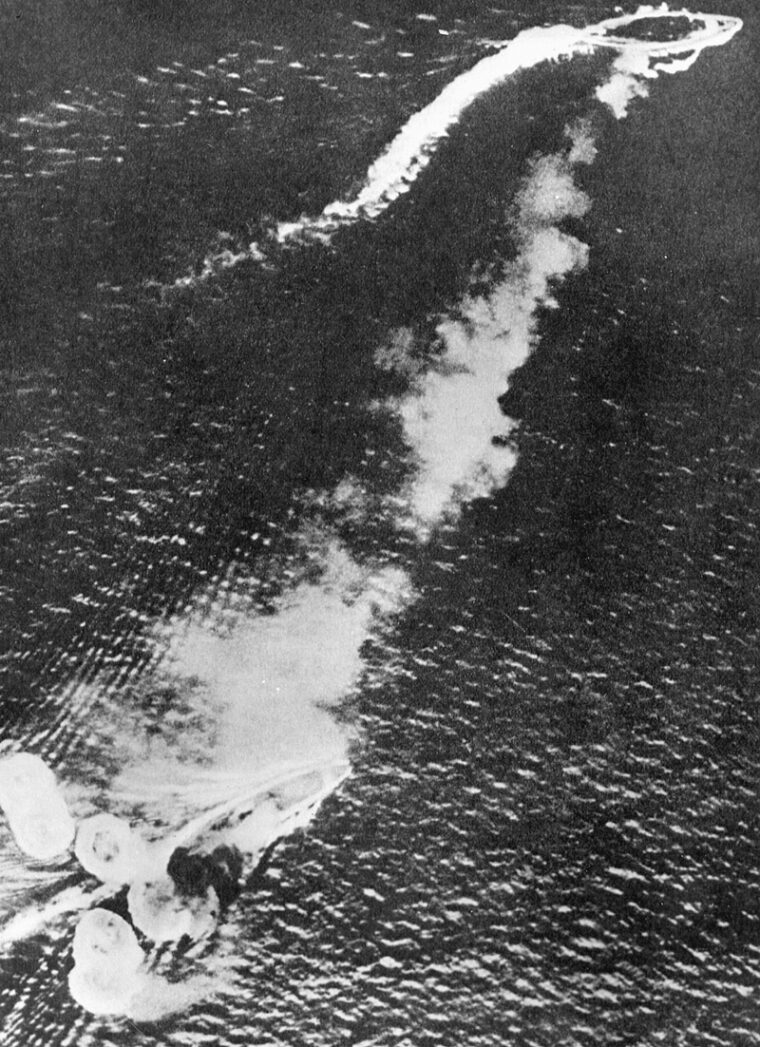

Despite frantic maneuvering by all of the British ships, the Japanese deployed their torpedo bombers from so many directions that they could not fail to hit their targets. Soon, Prince of Wales and Repulse were sinking. At last, British land-based planes appeared overhead. Too late to save their ships, they managed to chase off the Japanese, allowing Electra and her sisters to pick up survivors.

Once more, as with Athenia and Hood, “Lucky ‘lectra” prepared to receive the shocked and injured survivors. Drifting into the oil slick where Repulse had so recently been, the crew began pulling aboard as many men as possible. Oil and blood soon covered the rescued and rescuer alike. The decks were slippery with fuel oil fetched up from the sea with each oil-soaked man dragged aboard. Below on the mess deck, now a hospital, there was the stench of blood, chloroform, and fuel oil in the stifling air.

As many as 1,000 Repulse crewmen were crammed aboard the little destroyer. They stood tightly packed and barefoot on the blistering deck in an agony of loss, pain, shock and heat. Once again, Electra returned solemnly to port with a cargo of human misery.

The next few weeks saw non-stop activity. Electra escorted convoys of reinforcements into Singapore and convoys of wounded and civilians out. Meanwhile, the Japanese steadily advanced toward the “impregnable” city that everyone seemed to know was doomed.

Electra’s Final Engagement: The Battle of the Java Sea

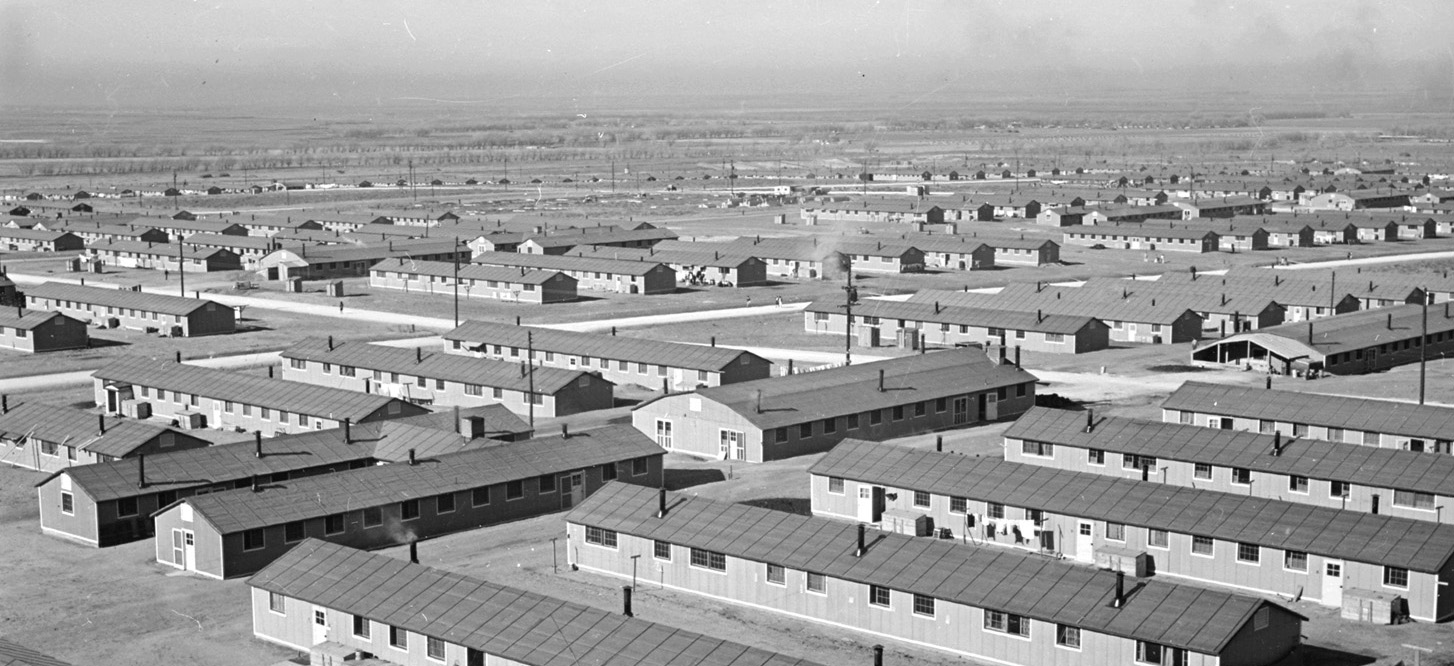

The destroyer was in Java when news came that Singapore had fallen. Electra was placed under a new command. The so-called ABDA force was the first Allied naval fleet of the war, American, British, Dutch and Australian ships combined under Dutch command. To protect the 500-mile Java coastline, the tiny armada was divided to cover the western and eastern shores.

Electra found herself on the eastern end of the island at Surabaya with her British sisters Jupiter and Encounter. They joined with five American and three Dutch destroyers, the heavy cruisers USS Houston and HMS Exeter, which was already famous for slugging it out with the German pocket battleship Graf Spee off Montevideo, and two Dutch light cruisers.

The little fleet put to sea on February 27, 1942, when their commander, Dutch Admiral Karel Doorman, learned of advancing Japanese transports. Instead of finding the transports, the Allied fleet ran into a Japanese squadron of cruisers and destroyers. The Battle of the Java Sea was on. Smoke was made, and firing commenced. Soon Exeter was hit in her boilers, lurched out of line, and stalled dead in the water. The Japanese advanced for the kill.

May knew his duty. He must protect the cruiser with his own life and that of Electra. Charging out of the smoke and into broad daylight, Electra found herself facing the entire Japanese force alone. Her gunners scored first, but Japanese shells came back thick and fast. Electra’s guns were put out of action one by one, and she began to list to port.

May gave orders to abandon ship as the shells kept slamming home. The Japanese destroyer Asagumo is credited with the death of Electra, but she herself was heavily damaged in the fight. Electra had done her duty. The Exeter was given a few precious moments to build up steam. She limped away to fight, and be sunk, another day.

As Electra turned over and went down by the bow, Japanese fire transferred to the survivors in lifeboats, adding to the long list of casualties. Advancing darkness spared the rest. That night, the American submarine S-38 surfaced and rescued 42 survivors. Five more were picked up the next day by the Japanese.

Dropped off in Surabaya, Electra’s surviving crewmen made their way by train to Java’s one remaining open port and from there by boat to Australia and safety. Electra’s war was at an end.

Author Glenn Barnett is a frequent contributor to WWII History. He lives in the Los Angeles area and enjoys writing about lesser-known historical events.

My Uncle Frank William Vincent died in the Battle of the Java Sea in February 1942. He was a Coder and only 20 years of age. He visited Cape Town and was hoping to settle there once he married his fiancé. I have tried to attach a photo of Frank but have not been successful. Perhaps if you reply to this email I will be able to attach it. My Mother, his Sister Phyllis Robins, never got over his death but I managed to get a book on the Battle of the Java Sea from the Home Office in London and she was able to distribute copies to her Sister in America. Many thanks, Val Hibberd, 21 October, 2020