by Pat Mctaggart

The concept of Soviet partisans participating in Russia’s wars was nothing new in 1941. During Napoleon’s invasion of the country in 1812, small bands of civilians harassed the French and their allies both before and after the retreat from Moscow. When the Kaiser’s army struck in World War I, the Germans were forced to pull units from the front line to deal with partisan activity in the occupied areas. (You can read more in-depth stories from the Great War and the soldiers who shaped the twentieth century inside Military Heritage magazine.)

Numerous bands of partisans were formed during the Russian Civil War. Red partisan detachments were particularly successful in Siberia, harassing the rear areas of the Whites and making a vital contribution to the communist fight in the Far East. The commander of the Urals Partisan Army, Vasilli Bliukher, was awarded the Order of the Red Banner for his leadership against the Whites. He was later beaten to death during the purges brought on by Soviet Premier Josef Stalin’s paranoia.

After the Civil War ended, Soviet leaders continued to publish works on the organization and effectiveness of partisans. Lenin addressed the subject in some of his works, and Marshal of the Soviet Union Mikhail Tukhachevsky published several documents dealing with partisan tactics. He also addressed the subject of antipartisan operations, dealing with both how to conduct them and how to counter them. Tukhachevsky was murdered on Stalin’s orders in June 1937.

By the summer of 1941, a semidoctrinal mind-set concerning the spirit and usefulness of partisan warfare had become part of the psyche of many Soviet citizens. For Party fanatics, there was no question about civilian resistance to any enemy threat. A sense of duty to the communist system made the choice to fight automatic. For many others, it would take time to make the decision to fight.

Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union, began on June 22, 1941. Although a few Russian commanders had their men in forward prepared position, at the risk of their own necks, the majority adhered to Stalin’s orders to do nothing to provoke the Germans. Stalin had disregarded information from several sources that pointed to a surprise attack, willing instead to believe that the non-aggression pact signed with Hitler in August 1939 would be good for at least another year.

The result of Stalin’s stubbornness was a disaster for the Red Army. During the first six months of Barbarossa more than three million Soviet soldiers were captured or killed. Around Kiev, the figure was more than 600,000, while the defense of Smolensk cost the Red Army about 486,000 men. Another 300,000 prisoners were taken at Uman. The staggering figure of killed and captured astounded the Germans, who were not equipped to deal with the massive influx of enemy soldiers.

Successful as the German encirclements appeared to be, the lines around the trapped Soviet armies were often porous. Remnants of many divisions escaped eastward through gaps in the German positions. Other small groups and individuals disappeared into the marshes and forests that make up much of western Russia. Even if they were trapped behind enemy lines, those men continued the fight, forming the nucleus of early partisan units.

Although Moscow expected local Party leaders to form partisan units in the event of an invasion, actual preparations, such as stockpiling food and weapons, were woefully inadequate. The swift advance of the Wehrmacht through Western Russia also impeded any initial partisan formation because German forces were literally at the doorstep before many officials knew what was happening.

Another factor was the hostility directed against Moscow from many inhabitants of western Russia, especially in the Ukraine and former Polish territory. During the initial stage of the war, the Germans were treated as liberators in many areas, with the local populace only too ready to point out communist officials.

Despite these difficulties, from the beginning attempts were made to form a truly civilian partisan movement in some areas. More than a thousand Party members were left behind in Belorussia, and more were ordered to stay in various other areas that would soon fall into German hands. For the most part, these men were used to organize communications networks and find safe houses and other hiding places in which build up weapons caches for future use.

Powerful Figures in the Party, the Secret Police, and the Red Army Vied for Control of the Soviet Partisans

At the end of June, Moscow finally sent out an official directive to the nation. In a June 29 proclamation, the Central Committee of the Communist Party and the Council of People’s Commissars directed local Party organizations to form partisan detachments and bring the war to the enemy. A mid-July order gave specific instructions on how the partisan groups should organize and what targets were priorities for destruction.

Detachments were to be composed of 75 to 150 men who were divided into two or three companies, and each company was subdivided into platoons. Large forested or swampy areas were deemed vital for cover and use for a base of operations, and care was given in explaining how to develop and distribute weapons caches. Instructions were given to make night raids on petroleum and ammunition dumps, railroad lines, airfields, and communication centers. Units were also told the best places to lay explosive charges and how to deal with attack, defense, and pursuit operations.

Once the Communist Party became engaged in the partisan movement, the vast Soviet bureaucracy kicked into gear. Committees were formed from the top levels of government down to local levels to regulate guerrilla activities. Powerful figures in the Party, the NKVD (secret police), and the Red Army vied for control of the partisan organization. The tactical and operational orders concerning partisan warfare finally ended up being controlled by the notorious political chief and head of the Main Administration of Political Propaganda of the Army and NKVD, Lev Mekhlis.

Mekhlis had a bloody reputation earned during the purges of the 1930s. A favorite of Stalin, Mekhlis ruthlessly ordered the executions of officers and men whom he thought did not show proper aggressiveness during the Russo-Finnish War of 1939-1940. Later in World War II, his meddling in military matters would cost the Red Army dearly in the Crimea and elsewhere, but his friendship with Stalin prevented him from ever receiving more than a slap on the wrist.

While Moscow struggled with organizational details, partisan units remained fairly passive throughout the summer and fall of 1941. Most of the active aggression came from detachments that had benefited from the influx of Red Army stragglers who found their way into the partisan camps. Experienced in weapons and tactics, the soldiers passed their knowledge on to the civilians in their group. It was these detachments that caused the first pinpricks to disrupt the lengthy German supply and communication lines.

Geography played a major role in early partisan actions. The vast forests and swamps in eastern Belorussia and the western Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic offered natural protection for units that would strike quickly before disappearing into the primitive countryside. German security units were reluctant to follow the partisans, preferring instead to stay close to the installations they were guarding. Those that did pursue were often on the receiving end of an ambush by unseen enemies.

One of the few partisan units that were able to organize effectively in those early days was a Belorussian detachment led by Mihay Filipovich Shmyrev. It was ironic that this man led one of the first successful groups since his combat experience consisted mainly of fighting anti-Soviet partisans during and after the Russian Civil War.

Shmyrev formed his detachment on July 9 with 23 menwho worked in a small factory that he managed. Their first weapons came from Soviet soldiers who were fleeing from the advancing Germans. More recruits were gleaned from Red Army stragglers and local civilians who were drawn to the cause.

Their first offensive action came on July 25 when Shmyrev and a squad of his men ambushed some Germans who were bathing in a river, causing the enemy 25 to 35 casualties and suffering no losses to themselves. Subsequent ambushes in August were directed against light-skinned vehicle convoys and other soft targets.

The unit was soon acknowledged by Soviet officials, who sent 12 Red Army soldiers to reinforce Shmyrev in early September. Supplies followed in the form of four heavy machine guns with 15,000 rounds of ammunition and a light and a heavy mortar. Although some of his men deserted in the waning months of 1941, new recruits sought out the elusive Shmyrev, who now had the means to cause the Germans more than a little trouble throughout the rest of the year.

As the Wehrmacht moved deeper into the Soviet Union, partisan units were ordered to step up attacks on rail lines in the occupied territories. The road system in western Russia was in pitiful shape before the war started. German tanks and armored vehicles made a bad situation worse as they moved farther east, churning up the few good roads and making the rest all but impassible for the supply trucks that came after them.

The gauge for the Soviet rail system was different from that of Germany, and construction battalions followed the German advance, changing the rails so that Wehrmacht supplies could be moved quickly to the front on German-gauge rolling stock. It was slow going, however, even with conscripted labor from the conquered areas. Early partisan attempts to disrupt rail supply lines were not very successful, and damage was usually repaired in a day or two. Nevertheless, the farther east the Germans went, the more tenuous this vital network would become.

Another major function of partisan units in the first months of the war was to find straggling formations that had been bypassed by the Germans and were now behind the front. Many of these refugee soldiers were brought back to the Soviet lines. In October, some 800 soldiers were rescued from encirclement in the Poltava area, while another partisan group was able to rescue the 3rd Army’s General V.I. Kuznetsov along with 600 of his men.

Zoya was Captured, Interrogated, and Severely Beaten by the Germans

Early partisan activity, scattered as it was, provided Soviet propagandists with many stories designed to incite hatred for the Germans while promoting sacrifice for the Russian Motherland. Nothing tugs at the heart of a Russian more than a tragic or sentimental story, and communist propagandists knew how to appeal to the soul of the people, be they fervent Party members or secret anti-Stalinists. One such story centered on a young girl named Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya.

Born in 1923, Zoya joined a partisan unit in the autumn of 1941. She quickly adapted to the rigors of partisan warfare, helping lay mines and performing reconnaissance work. In November she volunteered to enter the village of Petrischevo, which had a German garrison, to reconnoiter and to cause any damage she could.

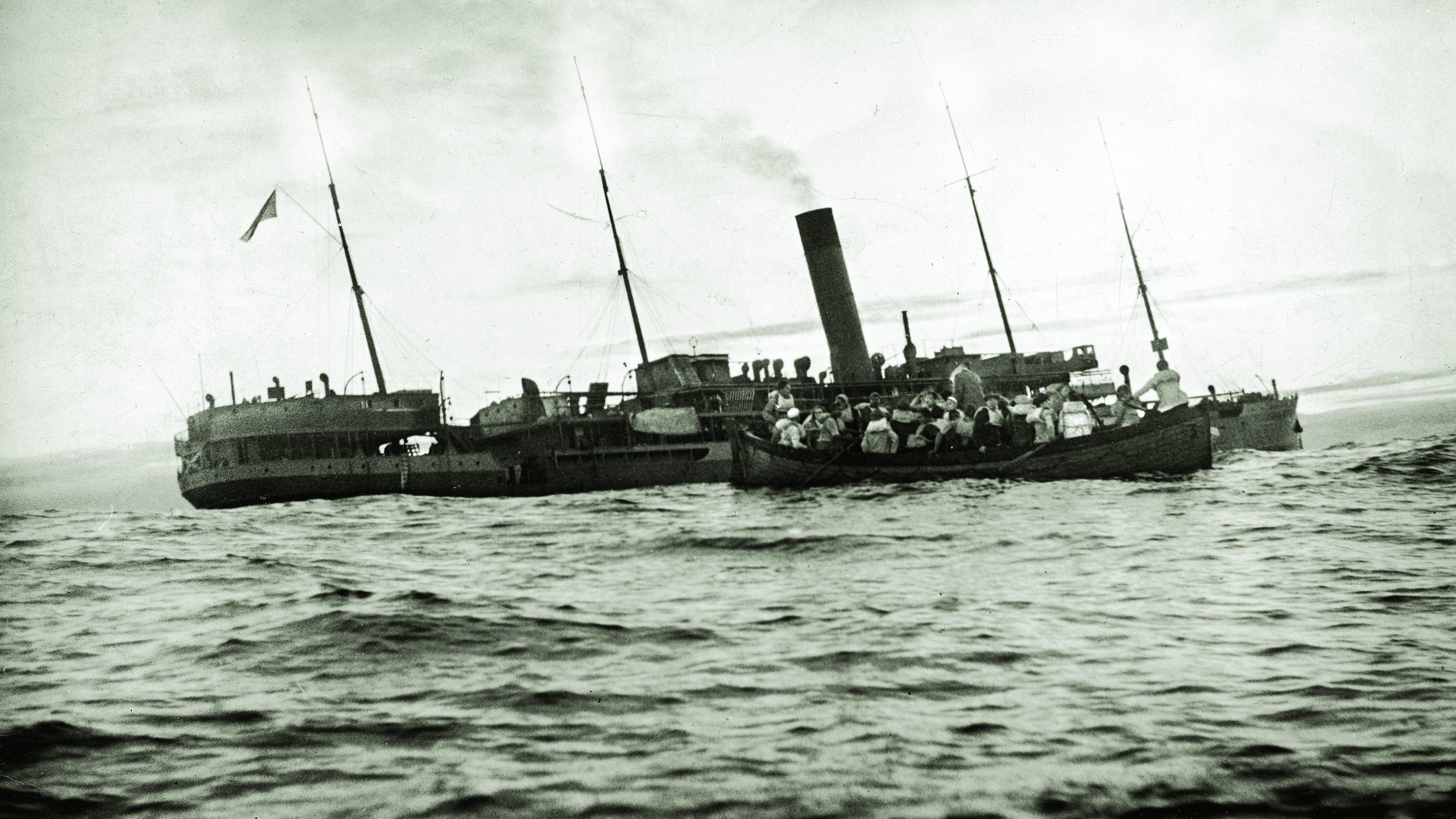

Zoya was captured a few days later and subjected to an interrogation that included severe beatings. According to a German sergeant who was present, the teenager remained silent during the entire process. Making no headway, the Germans marched her through the village half naked and hanged her. Zoya’s mutilated body was left on the gallows for more than a month until the village was recaptured by the Red Army.

Word of the young girl’s ordeal spread through occupied and unoccupied areas of the Soviet Union with lightning speed. Her story inspired patriotism that translated into a surge of volunteers for the partisan movement.

While the partisan movement struggled in its infancy, Mekhlis intervened with an order making political indoctrination of partisan volunteers a major priority. In some cases, potential partisan candidates were interviewed by NKVD teams that often turned away any volunteer that did not show proper communist zeal. Even as the Germans were approaching the gates of Moscow, Soviet political paranoia saw political reliability as more important than the necessity of defending the Russian Motherland with any means possible.

Overall, 1941 was a period for organizing the Russian partisan movement. Official Soviet histories claim that there were between 2,000 and 3,500 partisan detachments formed in the first six months of the war. No manpower figures are given, but even the number of detachments may be inflated due to the disorganization during these early months. A slow-moving Soviet bureaucracy, lack of weapons and concrete directions from Moscow, and the meddling of the Party resulted in a lack of action and semistagnation of the movement for the most part. That was soon to change.

One of the most important moments in Soviet partisan history came with the Red Army offensive in December 1941. Before then, much of the Soviet population in German-occupied Russia had either embraced the Germans as liberators (as it did in the Ukraine) or had just continued to struggle to survive, having traded one despot for another.

The Wehrmacht had seemed invincible in the summer and fall of 1941, and cries from Moscow to rise up against the invaders went largely unheeded. Calls to fight for the Motherland, with little mention of the Communist Party, drew some recruits, but the physical presence of German soldiers and the vast panzer and motorized columns heading east were a great deterrent for any overt action.

When the Red Army struck during one of the coldest winters in a century, the population of the occupied territories suddenly saw a different German soldier. Cold, frightened, and hungry, the once victorious troops were now heading west as Soviet forces smashed their lines. Even German reinforcements moving toward the front had a look of uncertainty about them. This did not go unnoticed within the local population.

Another important aspect of the Winter Offensive was fear. In the early days of the war, Soviet propaganda warned of dire consequences for anyone collaborating with the enemy. This seemed unlikely as the Germans advanced on every front. Although modern communication between the towns and villages of western Russia was almost nonexistent, the Russian peasants were kept abreast of events by the age-old method of word-of-mouth. News of the great encirclements of July and August spread from town to town, making it all the more difficult for Moscow to mask the seemingly devastating defeats that plagued the Red Army in those early months.

In December, that same primitive communication system began spreading word of Germany’s retreat. The propagandist’s cry of “The Red Army Is on the Way” now seemed to be a real possibility, causing many to rethink their earlier positions. Everyone remembered Stalin’s starvation and obliteration of the Kulaks after he took power, and the civilian and military purges of during the “Terror” of the 1930s were still fresh in people’s minds. Straddling the fence was no longer an option as word spread of the early Soviet victories in December. For many it was time to act because everyone knew that Stalin’s revenge would be terrible and swift. Reports from German rear-area commanders revealed a growing concern over increasing partisan activity.

On December 14, Heeresgruppe Mitte (Army Group Center) received a communiqué from one of its Korücks (Kommandant Rückwârtiges Armeegebeit—Commandant of an army rear area) stating: “As the Russians have become more active on the front, partisan activity has increased. The troops left to this command are just sufficient to protect the most important installations and, to a certain extent, the railroads and highways. For anti-partisan operations there are no longer any troops on hand. Therefore, it is expected that soon the partisans will join together into larger bands and carry out attacks on our guard posts. Their increased freedom of movement will also lead to partisans spreading terror among the people, who will be forced to stop supporting us and will then no longer carry out the orders of the military government authority.”

Osttruppen Units Were Known for Their “No Holds Barred” Approach to Fighting Partisans

Another Korück reported: “The situation in the Army rear area has undergone a fundamental change. As long as we were victorious, the area could be described as nearly pacified and almost free of partisans, and the local population without exception stood on our side. Now the people are no longer as convinced as they were before of our power and strength. New partisan bands have made their way into our territory, and parachutists have been sent in to assume the leadership of bands, assemble the civilians suitable for service along with the partisans who up to now have not been active, the escaped prisoners-of-war and the Soviet soldiers who have been released from military hospitals.”

It may be well to look at German rear-area security measures as partisan activity increased. Each field army had at least one Korück who was responsible for the security of a particular sector in the Army’s rear area. Sicherheits Divisionen (security divisions) were allocated to help guard rear areas and to participate in anti-partisan operations. These divisions had an infantry “Alarm” (alert) regiment composed of three battalions, a Landeschützen (regional defense) regiment of three to four battalions, and a guard battalion.

The Korück could also call on police units and independent SS battalions. Local volunteers (Osttruppen), especially in the Ukraine and Baltic States, were formed into battalion-size units to augment the German forces. These units were noted for their “no holds barred” approach to fighting the partisans, and the war behind the lines soon took on a particular savagery of its own in which prisoners were rarely taken by either side. As the partisan movement grew, rear-area security would cause a continuous drain on Germany and its allies’ manpower.

Small partisan actions during the offensive sometimes led to huge results. As the Germans retreated in the face of the Soviet onslaught, a partisan demolition group led by A. Andrianov destroyed one of the few remaining bridges across the Sestra River, creating a massive bottleneck on the east side of the river. The Red Air Force was notified, and in a large-scale attack Soviet aircraft destroyed approximately a hundred vehicles before the Germans could find alternate routes to the west.

If 1941 was a time of building for Soviet partisans, 1942 was a time of expansion and action. An example of increased operations against German supply lines took place about 15 miles east of Bryansk. On its own initiative, a German railway construction company started repairing a length of damaged track. Although the company was supposed to provide its own security, it proved inadequate when the partisans struck.

Communications between the company and its local headquarters suddenly ceased, and patrols were sent out to investigate. When a patrol finally stumbled upon the construction site, all it found were dead Germans. The entire company had been wiped out, and the partisans were long gone. No additional forces were available for security, so repair of the tracks was halted, depriving the Germans of an important supply line to the front.

In 1942, Moscow stepped up its control of partisan organizations, placing local units under regional commanders. Ten detachments in the Smolensk sector, for example, were centralized into a larger unit code-named “Batia.” Overall, Batia had more than 5,000 members, which made it able to fight regular battles with German security forces.

As the partisan movement gained impetus, more resources were relegated to the organization. Units were supplied with military communications equipment, and special radio channels were set aside specifically for partisan radio traffic. The Red Air Force at first dropped weapons and supplies by parachute, but by 1942 the larger partisan detachments had built airstrips in the forbidding forests and marshes that they called home.

Perfectly camouflaged, the airstrips were nearly invisible from the air, and the Red Air Force performed most of its supply operations at night with the partisans clearing away camouflage and lighting the airstrips with small fires set along the runway. Hand-picked partisans were also flown out of the occupied areas and were sent to a special school where they were given advanced training before flying back to their units.

Real cooperation with the Red Army began in earnest in 1942. The Winter Offensive had allowed Soviet units to push the Germans back more than 100 kilometers in some sectors of the front. During the retreat, partisan units harassed the Wehrmacht, cutting routes of withdrawal and leading Soviet assault units through supposedly impassable terrain to cut off and ambush the enemy.

The Soviet supply system became hopelessly overloaded in January 1942 as the result of the rapid advance. As the Winter Offensive stalled against determined German resistance, partisan units helped overextended Russian forces make their way back to their own lines.

In Nearly 5 Months the German Army Sustained More than 650,000 Casualties

Psychologically, the partisan movement far exceeded its actual accomplishments during the first winter of the war. Field Marshal Günter von Kluge, the commander of Heeresgruppe Mitte, reported, “The steady increase in numbers of enemy troops behind our front and the concomitant growth of the partisan movement in the entire rear area are taking such a threatening turn that I am compelled to point out this danger in all seriousness.”

He went on to mention the cooperation with the Red Army and pointed out that the partisans were becoming bolder, causing disruption of communications and diverting troops needed at the front. The real problem, however, was the uneasiness among the troops, not knowing where or how the partisans would hit next. Anxiety among German forces moving at night along the few passable roads caused depression and insomnia that sharply decreased their effectiveness when they got to the front lines.

Von Kluge was correct in one important area. From June 22, 1941, to November 6, the German Army had sustained more than 650,000 casualties. By the beginning of April 1942, another 900,000 casualties from all causes were incurred. Even with replacements and returning wounded, the Army was about 600,000 men short. This led to a realignment of security forces that left many of the smaller bridges and crossings behind the front completely unguarded.

The partisans were quick to react to the situation, demolishing numerous bridges and causing more supply headaches for the Germans. Frustrated, the German High Command called for security formations from its Axis partners to help with the problem. More pro-German local forces were also employed in antipartisan operations.

One of the most vicious antipartisan units was commanded by Bronislav Kaminski, an engineer of Polish extraction and a radical anti-communist. Kaminski had a force of about 1,500 men when the Germans encountered him during the Winter Offensive in a heavily partisan-infested area in the Bryansk sector.

Fighting under the emblem of the Tsarist St. George’s Cross, Kaminski carved out his own kingdom in the area, and by 1942 he had more than 9,000 men serving under him. The Germans had been unable to make any headway against partisans in the area, so they granted him a semiautonomous status in return for keeping up the pressure on the partisans.

Kaminski and his men were known for their extreme cruelty and ruthlessness. Partisan and nonpartisan villages alike were destroyed in the region, their citizens massacred under his reign of terror. Rape and plunder were the orders of the day as his men moved through the countryside, and even the German SS units operating in the area were appalled by the actions of the Kaminski Brigade. Kaminski was finally executed in 1944 on the orders of SS Lt. Gen. Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski.

Despite antipartisan activities like Kaminski’s, the movement kept growing. Working in cooperation with the Red Army and on their own, partisan forces continued to destroy German vehicles and communications lines. Some units even liberated towns held by enemy garrisons, which usually meant immediate execution for any surviving German soldiers. An example of the growth of partisan effectiveness can be found in statistics kept for the winter of 1941-1942. More than 1,800 German vehicles were destroyed, as were 650 bridges. Attacks against German rail lines resulted in the derailing of 225 trains.

Although the Germans had basically stabilized the main front by May, there were still formations of Soviet troops left behind the lines, cut off since the Winter Offensive. One of the largest was in the Bryansk-Smolensk-Vyazma triangle. Major General P.A. Belov and the remnants of his 1st Guards Cavalry Corps formed the nucleus of a group that also contained parachute troops and the survivors of the 33rd Army.

Working closely with partisan detachments, Belov’s forces struck weak points behind the German lines. The partisans provided vital information concerning German troop movements and strength, allowing Belov to hit the enemy at his most vulnerable positions before melting back into the countryside.

By mid-May, the Germans had taken enough. A two-pronged attack, code-named “Hannover,” was planned to eliminate the threat from Belov once and for all. A force of three panzer divisions, three infantry divisions, and one security division began the operation on May 24. Bridges destroyed by partisans hampered the attack as the Germans were forced to wait for engineers to replace the structures before they could cross the swollen streams and rivers in the area. Other partisan units shadowed the attackers, keeping Belov informed of the advance and allowing him to pull his forces out of harm’s way.

When the German prongs met on May 27, Berlin claimed about 2,000 prisoners taken and another 1,500 Russians killed. It was not the result that had been expected. Belov still had about 17,000 men in his command, but he knew that his time was running out. He decided to break through to the Russian lines using partisan guides to travel from one partisan-controlled area to another.

The Luftwaffe finally spotted the columns of Soviet troops, but by the time ground forces closed Belov and his men were already making their way through a densely forested area controlled by the Lazo Partisan Regiment. The Germans refused to follow for fear of well-laid partisan ambushes.

Soviet Estimates Showed That There Were Nearly 125,000 Effective Partisan Fighters by the End of Summer

Finally reaching the front, Belov organized his men and ordered an attack. A fierce fight developed, but Belov claimed that he brought at least 10,000 men to safety, even though he was flown out before the attack commenced. Thanks to partisan efforts, a large body of well-trained Soviet troops had been saved to fight another day while several German divisions needed at the front had been forced to deploy behind the lines in an effort to capture them.

The late spring muddy season gave the partisan units a chance to regroup. It had been a bloody winter for all involved in the savage fighting. Strength reports reaching Moscow showed a loss of about 20,000 partisans due to all causes. Official Soviet estimates give a total of about 70,000 effective partisan fighters operating in the spring of 1942. By the end of summer, that number had risen to about 125,000.

An important change in the partisan organization came in May 1942. Incompetence had its limits, even within the rigid Soviet bureaucracy. Although Stalin had ordered that a central staff be set up to control partisan activities in July 1941, Mekhlis and his boss, NKVD Chief Lavrenti Beria, continued to control the movement. That control was finally wrested from the NKVD when P.K. Ponomarenko became Chief of the Central Staff of the Partisan Movement on May 30.

The change effectively removed control of the partisans from the Party and moved it toward closer cooperation with the military. Attached to the Headquarters of the Supreme Commander (Stalin), Ponomarenko soon had staff personnel at several front and theater headquarters, working closely with the Army commanders to control partisan activities in their respective sectors.

Hitler’s thrust toward Stalingrad began about the same time that Ponomarenko assumed his new position. The German advance brought new areas under occupation and also provided the Wehrmacht with new antipartisan forces. The German Army showed remarkable tolerance toward most of the tribes they encountered while advancing across the steppes and into the Caucasus and was rewarded with a flood of volunteers from various ethnic groups in the area.

Don, Kuban, Terek, and Siberian Cossacks were formed into legions to fight the Soviets and to protect the precarious German supply routes. Thousands of Armenians, Azerbaidjanis, Georgians, and North Caucasians also joined German forces, as did the Kalmucks, a Mongolian nomadic people living west of the Volga River and northwest of the Caspian Sea. It is interesting to note that many of these tribes were Muslim or, in the case of the Kalmucks, Buddhist, and that the Wehrmacht took great care in providing each group with its own religious leaders or chaplains.

Most of these ethnic groups had been tyrannized by Stalin and the communist system, and they fought ruthlessly against Soviet partisan units being formed in the newly occupied areas. In the final years of World War II, they followed the retreating Germans westward. Most were handed over to the Soviets by American and British forces to be executed outright or to be sent to the Gulags to die.

The length of the German communications and supply lines all along the front made them prime targets, and partisan forces were once again ordered to concentrate on disrupting them. In the summer and fall of 1942, demolition squads carried out numerous attacks against fuel and supply depots and the German railway network far to the rear of the front. Hundreds of railway and highway bridges were destroyed, and more than 300 trains were derailed between June and November.

German forces reacted with more antipartisan operations. In actions such as Vogelsang (Bird Song), which took place north of Bryansk, German armored and infantry units scoured a 19,000-square-kilometer area in an attempt to root out and destroy their elusive quarry.

Between June and November More Than 800 Trains Were Derailed in Belorussia

A maze of forest trails bounded by almost impenetrable brush and forests gave the partisans ample opportunity to ambush the Germans at almost every turn. Lasting about a month, Vogelsang netted about 500 presumed partisan prisoners with another 1,200 killed, a rather poor showing for such an operation. The strain of the fighting can clearly be seen in vintage photos of the German troops taking part in the action.

German antipartisan operations may have hurt the Russian guerrillas, but did not stop them from continuing their attacks. The German rail system was still one of the partisans’ prime targets. From May to November, trains were derailed in the Leningrad sector. Between June and October, partisans in the Smolensk sector derailed more than 300 trains and another 226 were lost in the Bryansk sector. In Belorussia, more than 800 trains were derailed between June and November.

Hundreds of railway bridges were also destroyed during the last half of 1942. The Germans, already stretched to the limit at the main front, were forced to pull out more divisions to deal with the partisans. By the end of the year, 10 percent of the German field divisions on the Eastern Front had been switched from fighting the Red Army to performing antipartisan duties.

As 1942 waned, word of the impending disaster at Stalingrad spread across the occupied regions to Germans and Russians alike. German morale, especially in the supposedly secure areas, began to suffer. The news, coupled with the increased partisan activities along the supply routes, had a depressing psychological effect on troops in the town and village garrisons tasked with guarding bridges and railway lines.

Another important effect of partisan activity in the last months of 1942 was a decrease in food supplies received by the Germans from the occupied areas. As partisan detachments became bolder, villages that had once furnished meat and grain for the Wehrmacht supply organization showed a dramatic drop in production, making it more difficult for the Germans to live off the land.

Partisan units began entering the populated areas, taking what they needed and destroying the rest. Entire village populations were coerced into leaving their homes to seek sanctuary in the forests so that the fruits of their labor would not feed the hated Germans. Some left for patriotic reasons, while others left at the point of a gun. Assassins, targeting villagers who had become too friendly with the enemy, were also used by the partisans to increase tensions between occupation forces and the local population.

Korücks, under increasing pressure to pacify their respective sectors, pleaded with Berlin for more troops, but there were none to be had. With the impending loss of the Sixth Army at Stalingrad, the pleas fell on deaf ears. In desperation, more Ostruppen battalions were raised, but the quality of the men reporting for duty made them a questionable deterrent.

With the deteriorating military situation and the increase in partisan strength, the German High Command appointed SS Lt. Gen. Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski to the position of Chief of Anti-Partisan Forces in December. The 43-year-old von dem Bach had served in World War I, where he earned both classes of the Iron Cross. He had served as the senior SS and Police Leader in the rear area of Heeresgruppe Mitte since June 1941.

An avid National Socialist, von dem Bach had been forced to resign from the Reichswehr (the post-World War I German Army) for participating in National Socialist politics. He found a new home in Heinrich Himmler’s SS, where he became an SS organizer on the Austrian frontier. Rising rapidly in the organization, he proved his ruthlessness during the June 30, 1934, blood purge of the SA, or storm troopers, known as the Night of the Long Knives when he ordered a rival SS officer, Anton Freiherr von Hohberg un Buchwald, assassinated.

When the Germans entered the Soviet Union, von dem Bach oversaw the Einsatzgruppen murder squads that followed in the wake of Heeresgruppe Mitte. As a result of those activities, he suffered a nervous breakdown, liver congestion, nightmares, and hallucinations that had to be treated by specialists at an SS hospital in Germany. After being declared fit to return to service, he resumed his duties until assuming his new post.

With von dem Bach’s appointment, the partisan war entered a new era of savagery. Partisan leaders already knew of his reputation, and the various formations steeled themselves to face their new enemy. This was especially true of the Jewish partisan units that often had to fight a two-front war against both the Germans and the animosity of the Russian people.

There was a marked difference between the Jewish and non-Jewish partisan units. The non-Jewish partisans fought because of patriotic or communistic motives and could rely on the local population to give them supplies. Most fought knowing that their families, no matter what hardships they faced, would more than likely survive the war and that they would be reunited with their loved ones once the occupied territories were liberated by the Red Army.

Not so the Jews. Those lucky enough to escape into the forest knew that most would never see their families again. Many had witnessed firsthand the slaughter of Jews by the Einsatzgruppen, and those who hadn’t soon learned the truth. The Jewish partisans were not only fighting for their country, they were fighting for revenge.

Most Jewish partisan units received little help from the peasant population, which often hated Jews more that they hated the Germans. Nevertheless, they won grudging admiration from other partisan units for their daring raids against German targets. In Belorussia, a unit commanded by the Bielski brothers grew to include about 1,200 fighters, while another unit, led by Shalom Zurnin, had about 800 Jews.

Whether Jewish or non-Jewish, Russian partisan groups continued to grow in size during the first half of 1943. The spring muddy season brought a welcome respite from combat, and the lull was used to train new recruits and to accumulate supplies and ammunition.

In an effort to counteract the increasing danger posed by the partisans, von dem Bach ordered the creation of the Jagdkommando (Hunter Commando) in early 1943. These were independent units, usually of company strength, designed to attack the partisans in their own element. The Jagdkommando units infiltrated into the forests and swamps that contained partisan bases and stayed for extended periods of time.

They moved mostly by night, looking for any well-traveled path or trail that might be used by partisan forces. Living off the land, they were able to set up ambushes along those trails. The ambushes sometimes caused severe casualties to small partisan formations, but it was not enough to stop the recruitment of more Soviet locals, who easily replaced the Russian losses.

In the spring of 1943, Adolf Hitler was planning a battle designed to annihilate Soviet armies deployed in a huge salient in the Kursk sector. Massive amounts of men and equipment were sent to the area in preparation for the battle.

The Soviets were well aware of Hitler’s plans. Their own espionage system was privy to many details of the operation, and partisan sources kept the Red Army up to date on enemy troop movements and dispositions. Hitler kept postponing the offensive, code-named “Citadel,” so that even more divisions could be moved in for the attack.

German commanders grew more worried about the delays and the effects that partisan units in their rear might have on the operation once it finally got going. With postponement following postponement, the Army decided to use some of its field divisions scheduled for the offensive to secure, if only temporarily, the rail lines bringing vital supplies to the attack forces. Their mission was to eliminate as many partisan groups as possible in the weeks before the offensive, which was finally rescheduled for July 5.

Battle-hardened infantry and panzer units swept the Bryansk sector in several operations throughout May and June. The partisans took some fairly heavy casualties in German operations such as Osterei, Freischutz, Tannhauser, and Ziegeunerbaron, but the units still managed to keep their cohesion. For the most part, surviving partisans melted into the marshes and forests to reform and integrate new recruits for the upcoming battle.

Code Name “Rail War”

In addition to the military preparations for the coming German offensive, STAVKA (Soviet High Command) issued specific instructions to the Central Headquarters for the Partisan Movement to conduct large-scale actions against the enemy rail network. The Red Army planned a counteroffensive once the German attack had run its course, and the disruption of the German supply network was seen to be an instrumental part of the operation if it were to succeed.

Citadel began with some initial success, but on July 13, Hitler, nervous about the Allied invasion of Sicily, decided to call off the offensive. He ordered key SS panzer divisions to disengage and head to the Mediterranean Front. Both sides had suffered massive losses during the nine-day battle, but the Soviets had a powerful reserve behind the front line ready to strike when the time was right.

The Russian counteroffensive began on July 17 with the Southwest and South Fronts attacking the flank of Heeresgruppe Süd. Heavy rains gave the German divisions of Heeresgruppe Mitte a break from the Russian offensive—the Soviets unable to attack or advance due to mud. The Heeresgruppe commander, Col. Gen. Walter Model, told Hitler in no uncertain terms that his armies would have to withdraw to shorten the line. For once, Hitler agreed and the divisions of the Heeresgruppe began moving westward on August 1.

The partisan operation was code-named “Rail War.” During June and July, even as the battle at Kursk raged, ammunition, weapons, explosives, and demolition experts were flown into partisan bases in preparation for the massive venture. In Belorussia alone, 123 partisan units were detailed for demolition activities. Each unit was subdivided into demolition squads that were assigned specific sections of track to blow up. In the northern and central sectors of the front, between 200,000 and 300,000 sections were targeted to be destroyed.

Preliminary attacks took place in late July with the Soviet counteroffensive now in full swing. Partisan units succeeded in blocking a main rail artery south of Bryansk for two days, and by the end of the month the Germans reported more than 1,100 separate attacks on railways in the central sector.

As the divisions of Heeresgruppe Mitte began their August 1 withdrawal, all partisan units scheduled to participate in Rail War were placed on alert. They moved out to prearranged sectors and waited for the command to strike. The order came on August 3, just as the Germans were in the midst of their withdrawal.

During the nights of August 3 and 4, Heeresgruppe Mitte reported more than 4,100 railway demolitions. It was the same in other sectors of the front. In all, Heeresgruppen Nord, Mitte, and Süd had a combined total of 262 kilometers of tracks destroyed. Supply trains heading toward the front were derailed by the attacks, backing up rail traffic and turning German logistics at the front into a nightmare.

Without the necessary supplies and ammunition, Model’s Heeresgruppe Mitte was hard pressed to hold its new positions, which were being attacked by three Red Army Fronts. German repair battalions were sent out to restore the most vital sections of track, requiring more units to guard the workmen—men that were sorely needed at the front.

The 3rd Partisan Brigade Claimed to Have Blown Up 10,000 Sections of Track in August Alone.

In the Pinsk district of Belorussia, the Germans worked from early August until September 19 to repair sections of track that had been destroyed by the Imeni Lenina (In the Name of Lenin) Partisan Brigade. German trains were able to use the tracks for exactly one day before the brigade struck again. It was mid-October before the tracks could finally become operational once more.

The attacks continued up and down the front. In the Odessa sector in southern Russia, the 2nd Partisan Brigade, commanded by S. Kaplun, severed the Sarany-Luminets rail line, preventing its use from August 15 until October 19. The 3rd Partisan Brigade, operating behind the lines of Heeresgruppe Nord, claimed that it blew up 10,000 sections of track in August alone.

Despite the kilometers of track destroyed, the Soviet authorities in Moscow were somewhat disappointed with the August effort. Communist officials had demanded many more attacks than had actually been carried out, oblivious of the logistical requirements facing the partisan units. In reality, the partisans had done everything they could to help the Soviet offensive.

Their efforts were recognized after the war by Hero of the Soviet Union Marshal Georgi Zhukov. In his memoirs, he praised the partisan fighters, stating that they “contributed significantly to Red Army victories in the summer of 1943 at Belgorod, Orel and Kharkov.”

The partisan operation also had the effect of attracting thousands of new recruits. Soviet figures, which should often be taken somewhat skeptically, estimate a 250 percent increase in partisan fighters compared to the end of 1942. Even if the figure is inflated, there is no doubt that partisan units saw a significant increase in volunteers during the last half of 1943.

With its increased strength, the partisan movement continued to be a drain on German manpower. In the Nevel sector of Heeresgruppe Nord, partisans partially or fully controlled a 3,200-square-kilometer area of swamps and forests. Working with Party members, the partisans reestablished the collective farm system there and were even able to implement a crude postal system to communicate with officials in the unoccupied areas of Russia.

The Crimea also had its share of partisans that kept German and Romanian occupation troops on guard and on edge. A force of up to 8,000 fighters occupied key areas in the Yaila Mountains, disrupting supply routes and attacking German garrisons in the vicinity. Their operations became so troublesome that the Romanian Mountain Corps was ordered to wipe them out in late December 1943. In a week-long action, the Romanians claimed to have killed more than 1,000 partisans and captured more than 2,500 at a cost of 232 casualties to themselves. The surviving partisans melted away, forming new units to continue harassing the Germans and their allies.

In the early days of 1944, the Soviets launched two offensives—one against Heeresgruppe Süd and the other against Heeresgruppe Nord. The southern operation tore into the German line from Kirovograd to Korosten, forcing the Wehrmacht back more than 150 kilometers in some places. In the southern region of the Pripyat Marsh, partisan bands demolished the few rail lines in the area, totally disrupting the German supply network.

As the Soviets advanced, the partisans moved farther westward to set up new camps from which they could strike the enemy rear. More volunteers flocked to the cause, and German reports estimated that four partisan units with a combined total of nearly 9,000 men were operating in the rear of the Fourth Panzer Army, which was defending the sector directly south of the marsh.

The Red Army advance in the south slowly pushed the Germans back. By mid-April, the Russians had driven into Romania and were fast approaching the borders of Poland and Hungary. Once again, Soviet troops were helped by partisan units that derailed supply trains and demolished vital bridges that created choke points for German supplies and reinforcements struggling to reach the front.

In the north, the Russians launched an offensive aimed at breaking the siege of Leningrad and destroying the thinly stretched divisions of Heeresgruppe Nord. The offensive began on January 14 with thousands of shells slamming into the German positions. Tank and infantry units followed closely on the heels of the initial bombardment, breaking through the German front in several sectors.

Partisan units in the north were ordered to wait until the assault was in full swing before making their own attacks. The hard-pressed Germans, seeing no partisan activity in the rear area, released some security divisions and sent them to the front to try and stem the Russian tide.

As the offensive developed, the partisans were put into action, striking key communications and supply networks. The security units heading to the front were also attacked as their columns moved through the open countryside.

By January 16, the partisan attacks were in full swing in the north. Near Luga, a critical rail station and switching point was destroyed with heavy loss to the defenders. The main rail line supplying the XXXVIII Army Corps, which was desperately defending the Lake Ilmen sector, was blown up in more than 300 places. As the Red Army advanced, partisan attacks further to the west delayed the arrival of reinforcements desperately trying to reach the front.

Code Name “Bagration.”

The northern and southern offensives rolled forward until the spring rains turned the land into a vast quagmire. Both sides had suffered heavy casualties in the past few months, and the surviving troops were exhausted. As the war settled down to a semi-stagnant state, the partisan units continued to sting the Germans, albeit to a lesser degree than in the previous months.

The Russian offensives had pushed Heeresgruppe Nord and Süd back hundreds of kilometers, leaving Heeresgruppe Mitte occupying a massive bulge in the center of the Eastern Front. In Moscow, staff officers worked night and day in planning a new offensive that was hoped to crack the Germans once and for all. The planned offensive was code-named “Bagration.”

Operation Bagration would strike Heeresgruppe Mitte with the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Belorussian Fronts. According to Soviet sources, there were about 150,000 partisans organized into 150 brigades and 49 detachments behind the German front in Belorussia. Bagration was due to begin on June 22, but by the time the offensive opened the partisans were already in action.

On the night of June 19, partisan forces in Belorussia set off more than 9,500 demolitions on German rail lines, and the main lines from Mogilev to Vitebsk and from Minsk to Orsha were knocked out of action for several critical days. When the Soviet offensive began on the 22nd, the movement of desperately needed supplies and reinforcements was impossible, leaving units on the front line in a hopeless position.

As the Red Army rolled forward, partisans prepared river and stream crossing points that helped Russian tank and infantry units continue to drive west. Partisan units also assisted the Army by seizing and holding bridgeheads ahead of the advance and by cutting off German lines of retreat.

When Bagration was finally over in late August, the Germans had been pushed back almost 600 kilometers in several areas. Most of the Soviet Union had been liberated and Central Europe cowed at the approach of the Red juggernaut. Many of the partisan groups in the Soviet Union were subsequently disbanded, ending the Soviet partisan phase of the war in Russia. Some disbanded units were incorporated into the Army, but other units were sent into German occupied Poland and Czechoslovakia to continue the struggle.

The transplanted partisans had a twofold mission: They were to continue to disrupt German supplies and communications, but they were also ordered to contact communist partisans in the still occupied territories. The Soviet partisans helped form the nuclei of organizations that would eventually bring all of Eastern Europe into the Soviet camp once the war was over. When the Germans were finally defeated, these well-armed, battle-hardened groups represented a popular front that stamped out any democratic movements that dared to stand up against them.

Western historians have debated the effectiveness of the Soviet partisan movement for decades. One perspective describes the movement as an intricate part of the Russian victory, while the other says that the partisans were little more than an annoyance to the Germans. A 1956 U.S. Army handbook on the subject states, “The Soviet partisan movement had a certain measure of success, perhaps as much as a resistance movement can have when opposed by a first class military power.” Early post-war German histories and memoirs also tended to downplay the role of partisan units during the war.

It is clear, however, that Soviet partisans played an important part in several key battles during 1943 and 1944. Their positive effect on the morale of Soviet citizens was also important, as was their negative effect on the morale of the German soldier. It should also be remembered that just by their existence, the partisans forced the Germans to divert much needed units to secure their own rear areas at times when every man was needed at the front.

The debate continues, but in the former Soviet Union men in their twilight years still bring out their war decorations to show their grandchildren and great-grandchildren. The young ones, especially in the rural areas, look with awe at the now bent old men when they point to a certain decoration and announce with pride, “I was a partisan.”

Pat McTaggart is an expert on World War II on the Eastern Front and the author of the book Siege! about six epic sieges during the war in that theater. He resides in Elkader, Iowa.

Such fascinating history. We all owe a debt of gratitude to the partisans. Without their contributions Germany may not have been defeated.