By Arnold Blumberg

Frederick the Great’s prescription for warfare was simple. The Prussian monarch wanted “short and lively wars” that relied on swift, powerful, and decisive military operations. To achieve this goal, he emphasized battle rather than maneuver, making Frederick the most aggressive military commander of the 18th century. His practice went against the established consensus of military men, which demanded that maneuver be granted precedent, with actual battle to be engaged in only sparingly. This precept was echoed in the service regulations of the Saxon army, which stressed, “The greatest generals refrain from giving battle, except for urgent reasons.”

Frederick did not have that luxury. Aware that Austria, France, and Russia were planning to move against him in 1757, Frederick commenced the Seven Years’ War in August 1756 by attacking his southern neighbor, the Electorate of Saxony. A hard-fought battle against an Austrian army at Lobositz, northern Bohemia, on October 1, although a tactical draw, saw the Austrians fall back and abandon Saxony to Frederick’s mercy. By controlling Saxony, the king gained a number of advantages. First, he obtained the strategic initiative, which allowed him to set the tempo and direction of the war. In addition, Saxony provided Prussia with a buffer zone, shielding her southern frontier from Austria. Finally, holding Saxony subtracted a significant military force from the anti-Prussian coalition then forming, as well as gaining Frederick much needed financial resources to carry on the war.

Frederick’s Throne

Swift aggression was Frederick’s calling card, but it did not come naturally for the 44-year-old monarch. His father, King Frederick William I, had despised his son and heir, considering the younger Frederick a Frenchified, effeminate “flute player and poet.” The old king, grim, abusive, and cold hearted, cared for little but his burgeoning army, particularly his 3,000-man Guard of Giants, composed entirely of unusually tall men. Habitually clad in a blue military uniform, Frederick William scorned his son’s growing interest in the arts, stressing instead the more sober Prussian virtues of discipline, strength, and militarism. When he was 18, the prince rebelled, attempting to flee to England to marry his cousin, Princess Amelia. The king got wind of the scheme and had Frederick arrested and thrown into prison, where he was forced to witness the execution of his best friend, Hans Hermann von Katte, who had attempted to help the prince elope.

[text_ad]

Having learned a painful lesson in obedience, Frederick, upon inheriting the Prussian throne, was determined to outdo his father. Rapidly expanding the Prussian army (except for the Guard of Giants, which he happily dispersed), the new king forcibly united Prussia and seized the province of Silesia, creating a lifelong enemy in Austria’s empress, Maria Theresa, and inspiring a triple alliance among Austria, Russia, and France. England, on the sidelines, supported its Prussian kinsman diplomatically, but was too caught up in New World conflict and conspiracy with France to become involved in another land war in Europe.

Prussian Army Undersupplied

Forced to go it alone, Frederick opened the campaign season of 1757 with an offensive against the Austrians in Bohemia. A thrust into that region, Frederick hoped, would destroy enemy forces and supply centers and perhaps compel Maria Theresa to sue for peace. At the very least, it might force the Austrians to forego major military operations for the remainder of the year. In addition, intelligence had reached the king that Austria’s main allies—France and Russia—were slow in moving their own armies into the field against him, thus leaving the Austrians momentarily alone to face the Prussians.

To accomplish his overall purpose, Frederick launched four troop columns into Bohemia along a 130-mile front stretching from Saxony to Silesia. The move achieved complete surprise against the outnumbered and widely dispersed Hapsburg forces, commanded by the cautious and wholly incapable Prince Charles of Lorraine, brother of Austrian Emperor Francis Stephen. By late April, the Prussian juggernaut had rolled into Bohemia. Encountering little resistance, Frederick’s blue-coated soldiers came together just north of Prague on May 6. With 64,000 men under his immediate command, he was determined to attack the enemy that same day.

After leaving a strong garrison in Prague during the first days of May, Frederick’s opponent, Charles of Lorraine, had placed his 60,000 forces east of the town on easily defensible broken ground. Instead of fighting the Prussians before they united north of Prague and possibly defeating them in detail, Charles elected to force his enemy to attack him, with the threat of an unsubdued Prague at their back. He knew that Frederick needed to take Prague, a huge supply center, to alleviate the Prussian army’s growing supply problems. As long as Charles’s army remained a nearby viable threat, Frederick could not dare lay siege to the city. He did not have the manpower and resources to conduct a siege and fight the Austrians at the same time. He would be forced first to attack the Austrians on ground of their choosing. Even a drawn battle would cause Frederick to retreat due to supply difficulties. All Charles had to do was not lose.

Defying a Looming Defeat

The morning of May 6 revealed to Frederick that the Austrian position was too formidable to assault frontally. Looking for a more promising avenue of approach, the Prussian monarch found it on the Austrian right, where the high ground gradually sloped down to an area of open meadows. The king immediately put into motion the tactical elements of his operational theory of war: rapid movement within close proximity to the enemy to gain an opponent’s flank, followed by an attack with the greatest possible force before the enemy could react. Frederick was risking all in a single day’s combat.

At 7 am, he directed his army to move south-southeast across the Austrian front. Three hours later the Prussians were still not in position to carry out their planned assault. Worse yet, the Prussian lead elements were encountering unexpectedly bad terrain as they blundered into swamps, drained fishponds, and knee-deep silt that shielded the Austrian flank. It took a while, but the Austrians finally figured out Frederick’s plan. Fortunately for him, Charles did not initiate a counterattack on the struggling Prussians who were approaching the Austrian position piecemeal. Instead, the Hapsburg commander trained his artillery on the attackers followed by the gradual shift of cavalry and infantry to his right to block the Prussian advance. A fierce cavalry fight also developed between the antagonists, but neither party gained a decisive edge.

Meanwhile, additional Prussian infantry battalions, unsupported by friendly cannon due to the soft ground retarding the guns’ movement, continued to advance, all the time under intense enemy artillery and musket fire. Some 300 yards from their opponent’s line, the Prussian assault stalled. Field Marshal Kurt von Schwerin, one of Frederick’s most trusted military advisers, attempted to get the attack moving again but was cut down by enemy canister. Upon seeing the revered senior officer die, the Prussian line evaporated, and the men began running for the rear. Closely pursuing them were waves of Austrians who were checked only upon the timely arrival of Prussian reserves.

In the midst of a looming defeat, some Prussian field officers still glimpsed a chance for victory. The Austrian countercharge had created a gap between their right flank and the main army facing north. Enterprising Prussian officers—without Frederick’s approval—pushed all available troops into the gap, splitting the Austrians in two. As this was going on, Lt. Gen. Hans Joachim von Zieten restored order on the Prussian left and, beating back the Austrian horsemen facing him, threatened the enemy right with 24 cavalry squadrons. The Austrians, now menaced on both flanks, retreated to Prague, an exhausted Prussian army too badly bloodied itself to effectively follow.

A Relief Army For Prague

Frederick termed the Battle of Prague “one of the most murderous battles of the entire century.” It had cost the Prussians 18,000 men compared to 24,000 casualties suffered by the Austrians. Regardless of the carnage, the brutal contest had been indecisive. Looking for a way to compel Vienna to sue for peace, Frederick mounted a partial siege of Prague. He masked the town (he could not fully surround it) and in late May commenced a bombardment of the city. The shelling continued for nine days before Frederick’s siege guns ran out of ammunition.

While the Prussian monarch sought to capture Prague, Maria Theresa’s government was scorning a diplomatic settlement to the war. Instead, the Austrians cobbled together another field army in eastern Bohemia, 35 miles east of Prague, with Field Marshal Leopold Graf von Daun placed at its helm. One of his country’s most experienced officers, Daun had entered the Austrian Imperial Army in 1718 and rose from colonel to major general over the next 18 years. He fought against the Ottoman Turks during the 1730s. During the First and Second Silesian Wars against Prussia, he gained the reputation as a clearheaded subordinate, but made no record of achievement as an independent commander. In the interwar years he served as armaments minister and was a major military reformer. In 1756, Daun was promoted to field marshal. By nature cautious and by no means charismatic, Daun was nevertheless a skilled organizer with a good understanding of logistics and how to maneuver an army effectively.

By June the new army under the Austrian field marshal numbered 55,000 men. Its assignment was the relief of Prague, toward which it marched on June 12. Facing Daun’s force was a 25,000-man Prussian observation corps under Lt. Gen. August W.H. von Braunschweig-Luneberg, the Duke of Bevern. As Daun’s host rolled westward, he sought to turn Bevern’s right. Bevern, thoroughly outnumbered and thoroughly alarmed, called upon the Prussian king for assistance while ordering a retreat toward the town of Kolin to the northwest. Responding to the general’s plea for help, Frederick rushed to Bevern’s aid the next day with an additional 10,000 men. Skeptical of the reported strength of Daun’s approaching army, Frederick intended not to engage in a pitched battle with his new adversary but to maneuver the Austrians out of Bohemia and away from Prague. With that accomplished, the town garrison’s last hope of succor would evaporate and its surrender would be assured.

Frederick’s Army Assembled

On June 14, Frederick joined Bevern (Daun doing nothing to prevent their juncture), and for the next two days the newly combined Prussian force remained in camp. At the same time, Frederick ordered as many troops as could be spared from the siege lines at Prague to join him. In the interval, the Hapsburg commander took up a strong position along the heights above the Beczvarka Stream, his right resting on the village of Pobortz in the north and his left flank anchored on the hamlet of Hostich. The Austrian flanks were difficult to approach from the front due to the heights the Austrians occupied, with their left additionally secure due to the presence of a chain of lakes and ponds. In the center of their line, where the natural obstacles were not as formidable, Daun deployed the best of his infantry backed up by 19,000 cavalry.

With the arrival of the reinforcements from Prague under Prince Moritz Furst Anhalt-Dessau on June 16, Frederick’s total strength rose to 35,000 men. He immediately sought a way to attack Daun. Realizing the almost impregnable strength of his opponent’s position, the king decided to repeat the maneuver he had employed at the Battle of Prague, moving directly across the enemy’s front and attacking its right wing. On that side the ground appeared to slope downward and might conceal his approach.

On the afternoon of June 17, Frederick got his army moving in two columns to the north toward Planian. Observing the movement, Daun later ordered his own command to redeploy to the right. As a result, by the next morning the Austrians held a new line shaped like a dog leg with the main position facing north from the village of Probortz and running east for two miles to Przerovsky Hill. Daun’s left flank was guarded by the Beczvarka Stream and ran south along the water for a mile to Hotisch.

The first line of the Austrian position was held by the 11 infantry battalions of the Puebla Regiment. To its right, on Przerovsky Hill, were eight infantry battalions from the Andlau Division. Between Puebla and Andlau, General Karl von Stampach was stationed with six cavalry regiments. On the far right, General of Cavalry Johann B. Graf Serbelloni, with six horse regiments, was moving to form a new Austrian right flank. The Hapsburg second line was composed of seven infantry battalions under Lt. Gen. Claudius von Sincere, who was behind the Puebla troops, with three cavalry regiments to the rear of Stampach. Supporting the Andlau wing were seven infantry battalions under Maj. Gen. J. Ludwig Starhemberg.

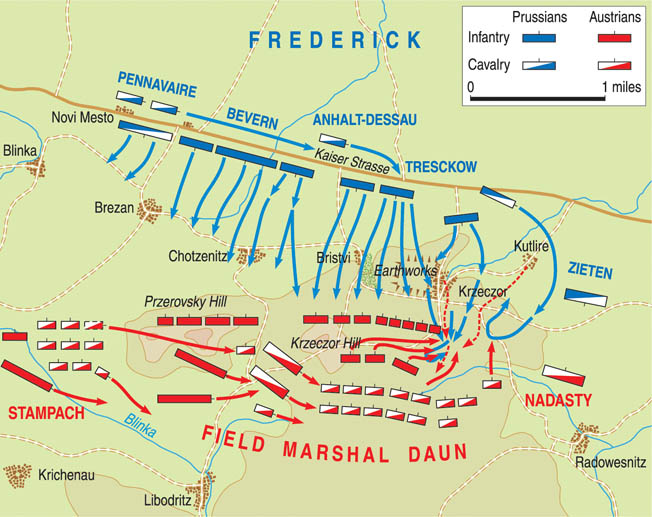

As Daun rearranged his forces, Frederick’s troops broke camp at 6 am on June 18. Mist hugged the ground as 50 hussar squadrons and four infantry battalions under Zieten led the Prussian army along the Kaiser Strasse, the highway that ran from Prague to Vienna, toward the Austrian right. Facing Zieten were Maj. Gen. Franz Leopold Nadasty and his light cavalry, which the night before had been assigned to guard Daun’s right flank. Aided by Croat light infantry, Nadasty continually skirmished with Zieten as the Prussian column headed east.

At 10:30 am, after five hours of marching, Frederick halted on the Kaiser Strasse and advanced his leading units 300 yards toward the Austrian-held ridge line. He also attempted to get a better view of the Austrian positions, which had thus far eluded him. His observations were sketchy at best, as they would be throughout the battle. Daun, who had no problem seeing what Frederick was up to, shifted three Saxon cavalry regiments to extend his right beyond Przerovsky Hill to Krzeczor Hill, as well as fortifying Krzeczor village situated one mile northeast of Krzeczor Hill.

The Prussian monarch was also pondering the importance of Krzeczor Hill, which he could not detect as occupied by the enemy. He decided to continue his march down the Kaiser Strasse, then turn to the right to move through Krzeczor village, ascend the hill, and roll up the Austrian right flank from there to the Beczvarka Stream. He issued orders for Zieten to clear Nadasty from the area around Krzeczor village. Once that was done, an advance guard under Maj. Gen. Johann von Hulsen, composed of seven grenadier and line battalions supported by a regiment of dragoons and six cannon, would secure Krzeczor village and a hill of the same name.

In support of Hulsen would be Lt. Gen. Peter von Pennavaire’s nine cavalry regiments and Lt. Gen. Joachim Friedrich Christian von Tresckow’s eight infantry battalions of the army’s left wing. These commands, along with Hulsen’s troops, would roll up the enemy line from right to left. Meanwhile, the army’s right wing, 17 infantry battalions and three cavalry regiments under Bevern, would remain on the Kaiser Strasse to fix the attention of the Austrians on the ridge. One hundred Prussian cavalry squadrons were stationed behind the infantry on the right wing, ready to exploit the expected envelopment of the enemy army.

Hard Resistance at Krzeczor

At 2 pm the Prussian army was on the move, with Zieten driving Nadasty and Hulsen advancing on the village of Krzeczor. Shortly afterward, Hulsen, under fire from enemy Croat infantry and artillery, attacked the town. A fierce firefight ensued for half an hour until the Austrian light troops abandoned the village and retreated to the Oak Wood, a mile south of the hamlet. As Hulsen fought his way through and beyond Krzeczor, Zieten and Nadasty continued their duel with each conducting numerous cavalry charges. Nadasty then organized a counterattack with the Croats in the Oak Wood, which pushed Hulsen back into Krzeczor. For the remainder of the battle, Zieten and Nadasty found themselves locked in indecisive fighting around the Krzeczor area, neither contributing to the final events of the battle.

The unexpected resistance at Krzeczor caused Frederick to suspend any contemplated movement of the rest of his army. He would wait and see what developed on Hulsen’s front before committing the bulk of his force to combat. Upon seeing the Prussian army cease its movement and hearing of Hulsen’s difficulties at Krzeczor, the usually calm and quiet Daun reportedly exclaimed, “My God, I think the King is going to lose today!” He ordered two battalions and four artillery pieces to extend his right at Krzeczor Hill.

The newly placed Austrians were soon hotly engaged with Hulsen, supported by 20 guns, when the Prussians once more issued forth from the village around 3 pm. Within a half hour, Lt. Gen. Heinrich K. Wied, with six fresh Austrian infantry battalions and two regiments of horse soldiers, came into view and occupied the front line facing north and anchoring his right on the Oak Wood. Trailing them were 12 artillery pieces. Quickly they suppressed Hulsen’s guns and inflicted grievous losses on his infantry.

“And Now the Battle is Lost”

As Wied put his men into place, Frederick implemented a new plan of attack. Instead of following Hulsen, his left wing would make for the Oak Wood below Krzeczor to turn the new Austrian right flank. Meanwhile, Tresckow’s nine infantry battalions, on Hulsen’s right, would assail Krzeczor Hill. To support this improvisation and stop the flow of Austrian forces from the center of their line moving to strengthen their right, Anhalt-Dessau would attack the enemy center on the ridge line with his nine infantry battalions. Frederick felt that portion of the Austrian line might be easily broken since forces from there had been moved to Daun’s right.

Three times Anhalt-Dessau refused to obey his sovereign’s order. His troops, out of position and facing murderous small-arms and cannon fire, did not have the benefit of friendly artillery support—most of the army’s guns had fallen well behind the advance. When he finally relented and ordered his men to advance, Anhalt-Dessau muttered, “And now the battle is lost.” His troops, seeing the formidable position they had been ordered to take, moved out hesitantly. Soon the assault stalled.

“Dogs, Do You Wish to Live Forever?”

As Frederick prepared his new initiative an opportunity came to him at 5 pm on another part of the field. Wied had unadvisedly moved his men toward Krzeczor, thus losing the flank protection of the Oak Wood on his right. Hit by two Prussian cavalry regiments under Maj. Gen. Christian Siegfried von Krosigk, Wied’s division folded and Austrian cavalry coming to its rescue were swept away by opposing cavalry. The threat to Daun’s right increased when Hulsen and Tresckow attacked Sincere’s front and flank. With the right flank gone and the battle apparently lost, orders went out for an Austrian retreat. But most of the Austrian commanders on the spot ignored the orders, and the fight continued unabated.

On the verge of collapse, Daun’s right flank was propped up in the nick of time by the movement of three regiments from Starhemberg’s command, while Serbelloni’s cavalry took over as the front line, facing the Prussians to the north. The Austrian right was saved by the valiant and steadfast fighting of the Botta Regiment, which held the line on the western edge of Krzeczor Hill against all comers.

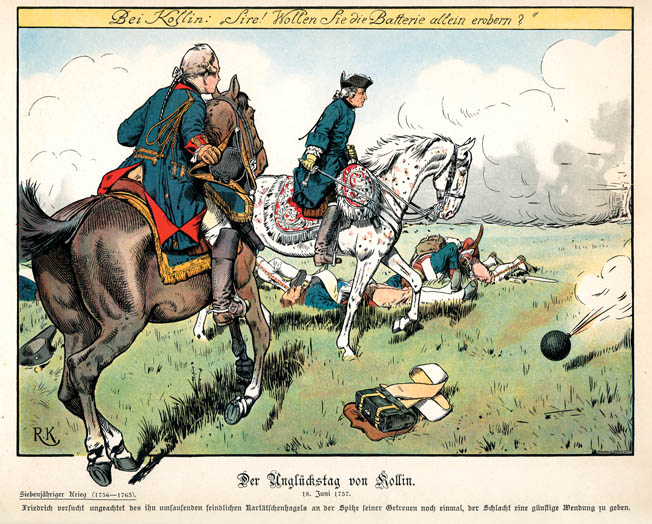

Farther to the west, in the sector commanded by Maj. Gen. Christoph H. von Manstein, two Prussian attacks on Przerovsky Hill were shot to pieces. Seeing this from his vantage point near Przerovsky Hill, Frederick was so frustrated at the lack of success that he attempted to personally lead an infantry charge against the height. Only 40 men followed him before Frederick’s aides pulled him back to friendly lines. Humiliated at the lack of support from his men, the king berated them, shouting, “Dogs, do you wish to live forever?”

About this time Daun moved elements of the Puebla regiment east to Przerovsky Hill, while his right-wing cavalry under Stampach moved to attack the Prussian extreme right. After some futile moves on the part of both parties to turn the other’s flank, Stampach retired behind the Pueblas’ left. The fighting then ended on that part of the battlefield for the rest of the day.

The Prussian’s Final Attack

By 5:30, the Austrians had been able to strengthen the shoulders on either side of the gap in their line near Krzeczor Hill. Hoping to finish off the enemy, Pennavaire was told to lead 20 cavalry squadrons up the slopes of the height. They were to be supported by some of Zieten’s horsemen and eight battalions of Bevern’s infantry. Neither came to Pennavaire’s aid. They were met by three cavalry regiments sent by Serbelloni that quickly retired from the field, leaving the Prussian mounted forces free to attack the two left-flank infantry regiments of Starhemberg’s command. Before they could deliver their attack, however, the Prussian cavalry was overwhelmed by masses of enemy cavalry that sent them racing back in disorder to the Kaiser Strasse.

At 7 pm, after gathering fresh infantry formations and three cavalry regiments from his right, as well as the remnants of Hulsen’s and Treschow’s commands, Frederick launched his final attack. His aim was to finally capture Krzeczor Hill by pushing through the still open gap in the enemy lines. Daun also rushed his last reinforcements, the Puebla and Andlau contingents, to the threatened area. Before they could arrive, the Prussians breasted the hill and struck the already decimated divisions of Starhemberg and Sincere. As Frederick’s blue-coated infantry passed through the gap in the enemy’s defense, they were hit hard on both flanks by nine Austrian cavalry regiments, soon joined by infantry from the Andlau command.

At 8 pm, the Prussian foot soldiers were being assailed from the rear as well by enemy cavalry and infantry. The Prussian force, broken into small groups, turned and retreated toward the Kaiser Strasse. An hour later, Hulsen, having recaptured the Oak Wood and Krzeczor village, also retreated to the highway after being threatened with encirclement. Zieten followed suit. During the night, under the guidance of Hulsen and Bevern, the demoralized Prussian infantry was ushered away from the battlefield to safety.

The End of Frederick’s Campaign

Reminiscent of the earlier battles at Mollwitz and Lobositz, Frederick departed the stricken field of Kolin before his army did. After delegating command of his army to Anhalt-Dessau, the king left for Prague on June 19. Stunned by his unexpected victory, Daun did not order a pursuit, which might have turned the orderly Prussian retreat into a rout. The Austrians did not leave the field until June 20, the same day the Prussians lifted the siege of Prague.

The next two months saw the Prussian monarch maneuver in northern Bohemia and Saxony, trying to bring the Austrians to battle again on his terms. His efforts failed despite the huge imbalance in the number of troops between the parties. The Prussian army had only 50,000 men and 72 guns, while the Austrians under Charles of Lorraine (again in charge of the Austrian field forces) fielded 105,000 soldiers and 350 cannon. With the withdrawal of Frederick’s army to its supply center at Bautzen, Saxony, on August 20, the campaign ended.

At Kolin, Frederick had suffered 12,000 dead, wounded, or captured, as well as the loss of 45 artillery pieces. The Austrians lost 8,000, including 1,300 dead. Prussia was defeated at Kolin for a variety of reasons: a fatal underestimation of Austrian strength; a rudimentary and inadequate personal reconnaissance of the enemy’s position; and the last-second change in plan from a flank march to a frontal attack on a strongly held position. Frederick also lacked enough reserves to exploit any advantages that came his way—and some did—during the battle. And finally, the calm and adroit way in which the king’s opponent, Marshal Daun, handled his own force against the best European army of its day proved decisive.

Kolin was not only a costly battlefield defeat for Frederick the Great. It also ended his chance of retaining the strategic initiative for the rest of the Seven Years’ War. In the years to come he would score a number of battlefield victories (Leuthen in December 1757 being the most significant), but most of his fights would be dictated by the actions of his enemies. Frederick would have to react to their moves, thereby slowly whittling down his own army by constant forced marches and brutal bloody battles against enemy armies outnumbering his own, usually on battlegrounds of the enemy’s choosing. This mode of warfare was not different from the “short and lively” wars that Frederick favored, and it came perilously close to bringing about the demise of Prussia as a nation state before the Treaty of Hubertusburg in February 1763 formally ended the conflict and restored the status quo ante bellum, leaving all sides bled white and exhausted.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments