By William E. Welsh

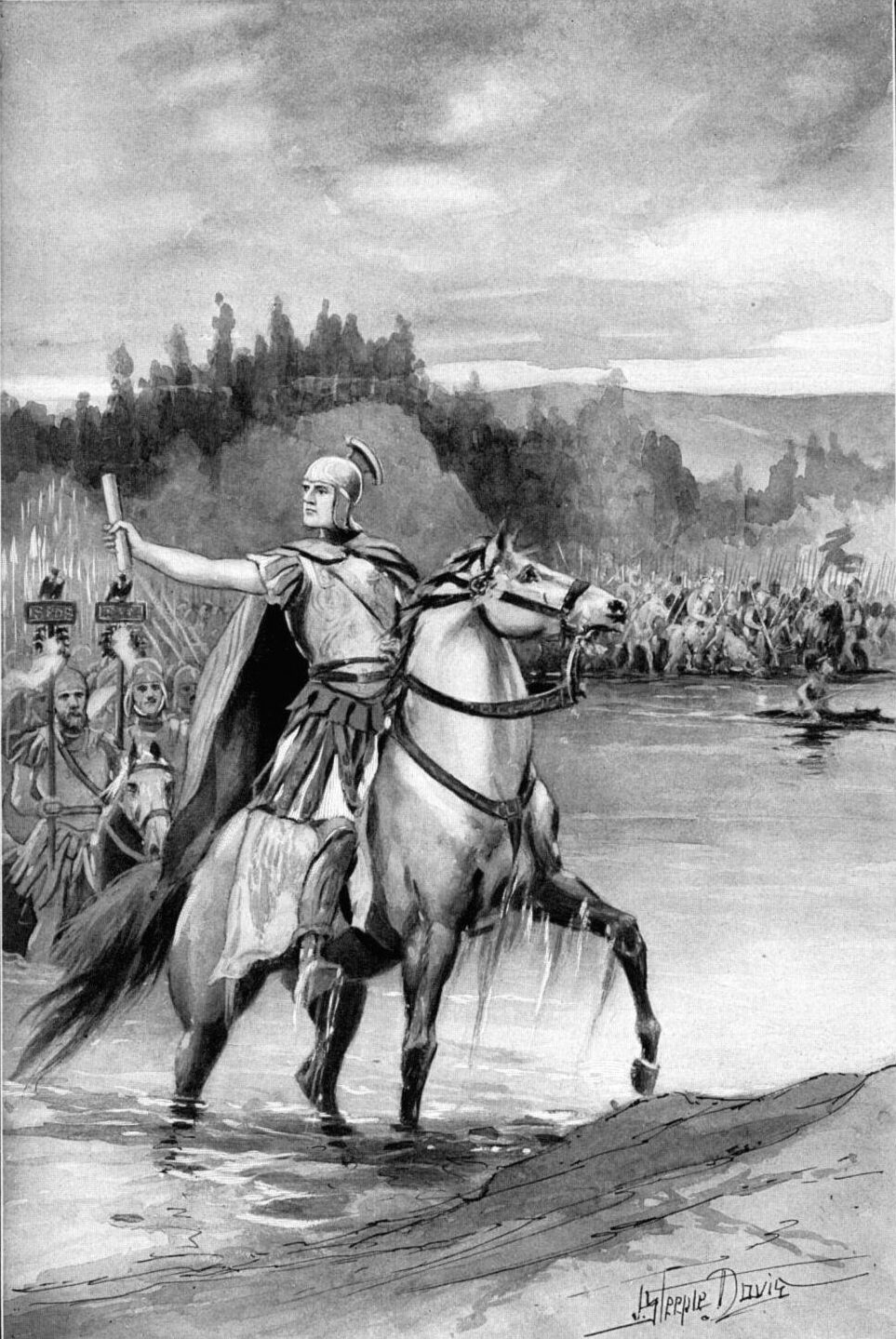

The snow-capped peaks of the Ceraunian Mountains stared down on the sturdy barks hunting for a suitable place to land on the coast of Epirus on January 5, 48 bc. Under cover of darkness, dozens of heavily laden transport ships had departed Brundusium on a southeastern course for Epirus. After a 15-hour voyage across the Strait of Otranto, during which they slipped silently past nearly 200 war galleys of the Republican navy anchored at Corcyra, the transports bearing 20,000 men under the command of 51-year-old rebel Roman proconsul Gaius Julius Caesar steered their ships toward a strip of sandy coastline near the village of Palaeste.

Using speed and surprise once again to his advantage and trusting in his fortune, the audacious conqueror of Gaul and leader of the populares faction of the Roman Republic had at last transferred seven of his loyal legions to western Macedonia where he intended to offer battle to 57-year-old Republican forces commander Gnaeus Pompey Magnus. While Caesar’s understrength legions debarked from their transports unopposed, Pompey was marching west from his base at Beroea along the Via Egnatia toward the Adriatic coast with a mighty host to await Caesar’s next move. Unknown to him, that move already had been made. The inevitable clash of the two surviving members of the First Triumvirate for control of the Republic was drawing near.

Caesar and Pompey’s Bitter Rivalry

The rivalry between Caesar and Pompey had always been present, but the establishment in 60 bc of the First Triumvirate in which the two statesmen allied themselves with each other and with Licinius Crassus had paid handsome dividends for each one of the participants. The triumvirate was an unofficial political alliance established to grant each participant the political objectives he desired in return for supporting the aims of the other two members. For Caesar, whose political career was on the rise, it meant serving as consul, a significant step up from his previous service in various magisterial posts and priesthoods. When Caesar was elected consul in 59 bc, he ensured that the principal objectives of his two fellow triumvirs were carried out. Pompey enjoyed a political settlement that resulted in land grants to veterans of his campaigns in the east, while the wealthy Crassus benefitted from favorable revisions to certain tax laws.

The highly ambitious Caesar carried himself as if he had already achieved greatness, although he had barely tasted it by the time he entered the First Triumvirate. Caesar hailed from a patrician family; however, he chose to align himself not with the conservative optimates faction, which dominated the Senate, but instead with the populares faction. His attraction to the populares faction likely stemmed from a desire to play up his connection to the middle-class reformer and consul Gaius Marius, who had married his aunt Julia.

In contrast, Pompey had achieved greatness by the time he agreed to participate in the triumvirate. His military career stretched back to service under Marius’s rival, the consul and dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla, under whom Pompey fought in Italy, Spain, and Africa. In 80 bc, he received the epithet “magnus” for his brilliant generalship in Africa. A decade later, his reputation as a sterling commander was again proven when he cleared the Mediterranean of pirates and embarked on a diplomatic and military campaign in the east from which he returned a wealthy man. His chief attributes as a military commander were an amazing attention to detail and a brilliant knack for combined operations involving naval and land forces. His vast military experience stood in stark contrast to Caesar’s dearth of military experience. For this reason, among others, Pompey held the younger man in disdain.

Caesar used his superb negotiation skills to establish the triumvirate, which initially was a secret alliance, with the two older statesmen. It was an odd coalition because Caesar and Pompey distrusted each other, as did Pompey and Crassus. Nevertheless, each member saw the triumvirate as an expedient way to attain the political objectives he desired.

Caesar’s Rise in the Public Eye

To achieve the military fame he so desperately longed for, Caesar arranged for himself a governership over Cisalpine Gaul, Transalpine Gaul, and Illyricum. When the three triumvirs met again in 56 bc, Caesar was allowed to renew his governership of those provinces while Pompey and Crassus assumed governerships of Spain and Syria, respectively. Crassus perished in 53 bc at the Battle of Carrhea when his army was soundly defeated by the Parthians.

Without question, Pompey was the most powerful statesman in the Roman Republic at the time of Crassus’s death. However, Caesar’s military and engineering feats in Gaul captured the imagination of the Roman people. In 55 bc, Caesar bridged the Rhine and in the same year sent the first Roman expedition across the English Channel to Briton. His war chest was filled with riches gained during aggressive campaigning in Gaul, and he distributed bribes as needed to ensure he retained a measure of support in the Senate. Nevertheless, Pompey remained the Senate’s favorite in large part because its members believed they could manipulate Pompey more easily than the headstrong Caesar.

“The Die is Cast”

Having built his military reputation and wealth after nearly a decade campaigning against the Gauls, Caesar desired a second consulship on the expiration of his second term as governor of the territories under his direct control. His enemies in the Senate wanted him to travel to Rome in person to seek the office. To do this, he would have to step down from his governorship and enter Italy without the security of his loyal legions. Caesar was all too aware that this would put him in a highly vulnerable position since his enemies wanted him prosecuted on various charges. Because of this, he requested that he be allowed to run for the consulship in absentia.

Caesar’s enemies in Rome would not hear of this. The outgoing consul in 50 bc, Gaius Marcellus (Minor), with the support of the two incoming consuls for the following year, gave Pompey a commission in December 50 bc to protect the state in the face of possible aggression by Caesar. Caesar was in Cisalpine Gaul when he received an ultimatum from the Senate on January 2, 49 bc, that he disband what remained of his army or face arrest as an enemy of the state.

When he received the ultimatum, Caesar knew that negotiations to attain his ends were no longer possible. Notifying the legions loyal to him to await his orders, he marched with the XIII Legion to Ravenna on the Adriatic Sea to ponder his next move. On the night of January 10, under the cover of darkness, he departed Ravenna traveling south along the Adriatic coast. A short distance from the town, he reached the Rubicon River, which marked the border between Cisalpine Gaul and the Roman Republic. He stepped out of his carriage to weigh his options one more time. After a short time, he made up his mind. “The die is cast,” said Caesar, returning to his carriage, which then rumbled over the bridge into the Republic. A short distance behind him tramped 5,000 men of the XIII Legion accompanied by several hundred horsemen.

Pompey Flees East

Four days earlier, the Senate had passed an emergency decree that gave Pompey a military commission to defend the Republic. Fearing he might be captured by Caesar without a fight, Pompey took the unprecedented step of abandoning Rome on January 17.

Pompey retreated to Apulia where he managed to assemble five legions of loyal troops. Knowing they were no match for Caesar’s veterans, he led them south to Brundusium. Arriving at the Adriatic port on February 25, he began preparations to transport his army by sea to Macedonia where he planned to recruit additional forces that he intended to mold into an army capable of meeting Caesar on equal terms.

At Brundusium, Pompey could only put his hands on enough ships to send half his army across the Adriatic Sea to Epirus at a time. He sent the first half across on March 4, but he remained behind to ensure that the remaining half of his army was not hindered in its efforts to embark for Epirus.

Caesar attempted to prevent Pompey from leaving Brundusium with the rest of his army by sealing off the port from its land side and also attempting to build a mole that would prevent the transport ships from reentering the harbor. Despite this, the Republican ships were able on March 17 to slip past the uncompleted barrier and board Pompey and his remaining troops for the voyage to Epirus.

By establishing his primary base of operations in Macedonia, Pompey would have at his disposal the formidable military resources of the Republic that were deployed in the eastern Mediterranean. What’s more, he would be able to use the Republic’s fleet to transport loyal forces from Spain and Africa to Macedonia for assimilation into his army.

Caesar Marches on Spain

Caesar realized that if he defeated Pompey’s army in Macedonia he might still have to contend with legions loyal to Pompey in other parts of the Republic. At the time of his escape to Macedonia, Pompey still had seven loyal legions stationed in Spain. Rather than face the proposition of having to fight a two-front war, Caesar resolved to crush Pompey’s legions in Spain first before pursuing his adversary in Macedonia. With nine legions under his command, Caesar spent the remaining months of 49 bc clearing Spain of Pompey’s forces. Throughout his conquest of Italy and Spain, Caesar pardoned the captured legionnaires and did his very best to persuade them to join his army.

During that time Pompey, whom the Senate-in-exile at Boroea had given the title of commander in chief of the armed forces of the Republic, had nearly doubled the size of his army. By December, the Republican army comprised nine legions, including the five initially raised in Italy, one from Cilicia, one from Greece, and two from Asia. Pompey also had summoned his trusted legate Scipio Metellus to march to his aid with two legions under his command in Syria. In addition, Pompey had recruited a large number of mercenaries, including 7,000 cavalry, 3,000 archers, and 1,200 slingers.

Pompey’s Miscalculation

After spending just 11 days in Rome after his conquest of Spain, Caesar departed in mid-December for Brundusium where he intended to sail to Epirus in the same manner as Pompey. Caesar already had dismissed the idea of an overland march through Illyricum as a risky proposition primarily as he would be exposing his army to hit-and-run attacks by hostile tribes in the province. Moreover, by sailing directly to Epirus, Caesar was confident he would be able to block any attempt by Pompey to return to Italy by sea.

Unfortunately for Caesar, the small fleet he had commissioned to be built in the Adriatic while he was campaigning in Spain had been captured and incorporated into Pompey’s navy. This meant that, just as Pompey had done before him, Caesar would have to ferry his army to Epirus in two crossings, both of which would be subject to possible discovery and attack by Pompey’s large navy based at Corcyra.

Landing with seven understrength legions south of the village of Palaeste on the morning of January 5, Caesar moved quickly to secure as much territory on the hostile coastline as possible before he encountered his adversary. Marching north, he secured the towns of Oricum and Apollonia without interference.

Unknown to Caesar, Pompey was marching slowly west on the Via Egnatia to establish a winter encampment on the Adriatic coast. Pompey, who had not yet joined forces with Scipio, mistakenly believed he had several more months to train his recently assembled army before the campaigning season began in earnest. At the time of Caesar’s landing, the Republican army was still several days’ march from the coast. When Pompey was notified en route of Caesar’s unexpected arrival by sea at Palaeste, the Republican army commander pressed his troops forward as fast as possible.

Race to Dyrrachium

Caesar’s vanguard struck out for Asparagium, and Pompey arrived at the town first astride his adversary’s route of march. The two armies faced off on opposite sides of the River Apsus to consider their next moves. At that point, Caesar learned that the Republican fleet had captured his squadron of 30 ships. This meant that Marc Antony’s arrival with badly needed reinforcements was delayed nearly three months until fresh ships could be procured for the transport of the remainder of Caesar’s army.

On April 10, Antony landed with four full-strength legions and 800 cavalry at Nymphaeum, a town situated 50 miles north of Caesar’s position. Pompey promptly broke camp in an attempt to intercept and defeat Antony before he could link up with Caesar. The conqueror of Gaul also broke camp to hasten his junction with Antony. Both Caesar and Antony eluded Pompey and met up at Elbasan, where the Via Egnatia debouched from the mountains onto the coastal plain. In response, Pompey fell back on Asparagium.

With control of the western end of the Via Egnatia in his hands, Caesar dispatched Domitius Calvinus with two legions and 500 cavalry to march east along the highway that traversed the Candavian Mountains to intercept Scipio, who had by that time arrived in eastern Macedonia. Caesar also sent Lucius Longinus south with one legion to Thessaly and Calvisius Sabinus into Aetolia with five cohorts. Longinus and Sabinus were to establish grain convoys to sustain the main army during its military operations in Greece.

With just seven legions to Pompey’s nine, Caesar retained the initiative by advancing on Pompey in his new position at Asparagium. When Pompey declined to accept battle at that location, Caesar feigned withdrawal to Elbasan but actually turned north off the Via Egnatia and raced across the foothills toward Pompey’s supply base at Dyrrachium. When Pompey discovered that he had been duped, he broke camp and by a forced march rushed to reach Dyrrachium before Caesar did.

Caesar won the race and by mid-April had established a military camp two miles south of the city, which was held by a small garrison of Republican troops. Pompey established his camp two miles south of Caesar’s camp on high ground known locally as the Petra. Caesar immediately undertook to build a fortified wall around Pompey’s position, which eventually stretched for 17 miles. Pompey responded by building an interior wall to protect his troops that stretched for eight miles and allowed for a no-man’s land between the two structures. Although Pompey could still supply his army by his open outlet to the sea at his back, he would find it difficult to provide sufficient water for his men and forage for the horses.

Caesar’s Rout

For nearly two months the armies remained in a stalemate at Dyrrachium. The decisive action that ended the siege occurred when a handful of Gauls, who had defected from Caesar’s army, informed Pompey that his foe’s left flank was vulnerable. The Gauls told Pompey that Caesar’s engineers had not yet finished a section of wall facing north toward Petra, nor had they completed a section facing south to prevent a possible amphibious attack by Republican forces from the south.

Pompey quickly devised an operation involving land and naval forces designed to exploit the vulnerability. Under cover of darkness on the night of July 8, Pompey moved six legions to the southernmost sector of his encampment along the coast. He also assembled several cohorts of light infantry and missile troops who boarded ships in the darkness and landed in two places at dawn on July 9. One group landed south of the outer-facing wall, while the other landed in the no-man’s land between the outer- and inner-facing walls. Just after sunrise, Pompey’s troops swept forward. They easily overran the startled forces who stood watch on the southern sector of Caesar’s fortifications. No large group of Caesarean troops was positioned nearby to contain Pompey’s raiders.

When Caesar arrived on the scene and launched a counterattack with three legions that afternoon, he discovered that Pompey’s troops already had begun building new redoubts inside and outside of the outer wall. Pompey met Caesar’s counterattack with five legions and sent his cavalry to harass the enemy’s rear. Outnumbered and in fear that they would be cut off, Caesar’s veteran troops decided to flee rather than stand their ground. Caesar dismounted and removed his helmet so that his men could see his face. He then began to loudly berate them for their cowardice.

When Caesar moved to block one group of fleeing men, a standard bearer in the group aimed the pointed end of his standard at Caesar to threaten him. With lightning speed one of Caesar’s bodyguards swung his sword through the air and hacked off the arm of the legionnaire who had leveled the makeshift weapon at his commander. The routed legionnaires could not be rallied until they reached the camp of the IX Legion a mile away.

Caesar lost about 1,000 legionnaires in the hard fighting on July 9 at Dyrrachium. Although Pompey’s army lacked the experience campaigning that Caesar’s army possessed, its commanding general compensated with clever tactics to offset his disadvantage. With Pompey in firm control of the seas, Caesar could not afford a war of attrition since there was no way for him to receive reinforcements by sea from Italy.

Realizing that Pompey had gotten the best of him at Dyrrachium, Caesar broke off the siege and retreated south through Epirus before turning east to cross the Pindus Mountains into Thessaly using the same route taken by Longinus in April.

Meanwhile, Pompey detached 15 cohorts to remain at Dyrrachium under the command of Cato the Younger before marching east on the Via Egnatia to unite with Scipio. His intention was to fall on Calvinus’s detached force of two legions and annihilate them, but Calvinus’s troops escaped south through the mountains toward Aeginium in western Thessaly. By that time, Caesar had arrived at Aeginium, and it was at that city that Calvinus’s force rejoined the main army. On August 1, Caesar crossed the Enipeus River and made his camp on the north bank astride the road to Pharsalus.

“We Shall Conquer Nobly, Caesar”

Pompey and Scipio reunited without opposition at Larissa. On August 5, Pompey marched south toward Pharsalus in search of Caesar. When Pompey learned that Caesar was blocking his route of march, he ordered his generals to turn off the road and establish a fortified camp on a hillside a few miles northwest of Caesar’s camp. Pompey, whose army was well supplied through the ports of eastern Macedonia, was in no hurry for a battle. By choosing a strong position in the foothills, he hoped that Caesar, who still had supply problems, would become impatient and attack him in his fortress-like position.

On the morning of August 6, Caesar led his army out of camp and formed up on the flat ground in sight of Pompey’s camp to offer battle to the defender of the Republic. Pompey declined the invitation. Caesar did the same for the following two days in which he received the same response from Pompey. Convinced that Pompey would not concede to do battle on open ground, Caesar ordered his army to break camp on the morning of August 9 and prepare to march northeast in search of grain to replenish its supplies. Caesar believed his army was better acclimated to the hardships of a mobile campaign than his enemy, and he was optimistic that an opportunity would offer itself for him to destroy the Republican army in another location.

Pompey was under severe pressure by the senators in exile who accompanied his army in the field to accept battle with Caesar on the Plain of Pharsalus. Once the Republican army was victorious, they reasoned, it could promptly return to Rome to restore order. Pompey himself believed that he needed to defeat Caesar soon to retain his reputation as a great general with Rome’s client kingdoms in the east. For these reasons, Pompey instructed his generals to march their legions onto the flat ground as a way to indicate that the Republican army was at last willing to do battle.

When he realized that Pompey’s army was marching out of its hillside encampment, Caesar immediately countermanded his earlier order. He instructed his engineers to knock down the walls around the camp and fill in the ditch that surrounded it so that the troops could march into battle without becoming disorganized. Officers and soldiers alike were eager to redeem themselves for the humiliation they had suffered at Dyrrachium.

As Caesar prepared to ride into battle, he spied one of his best warriors preparing for the bloody work ahead. Caius Crastinus, a senior centurion of the X Legion, led an elite unit of hand-picked shock troops, whose purpose was to start the infantry attack for the legion. As a centurion, Crastinus was trained to lead by example, and it was second nature to him to put himself in harm’s way to inspire those following him.

“Caius Crastinus, what are our hopes, and how does our confidence stand?” Caesar asked.

“We shall conquer nobly, Caesar, and I this day will deserve your praises, dead or alive,” Crastinus replied.

Deploying For Battle

On the morning of the battle, Pompey’s army consisted of 47,000 infantry and 6,700 foreign cavalry. His 11 legions were divided into 110 cohorts that averaged about 430 men each.

In contrast, Caesar had 22,000 men and 1,000 Gallic cavalry. By the time the battle began, he had reorganized his heavy infantry into nine legions that were composed of 80 cohorts and averaged about 275 men. Although Caesar was outnumbered more than two to one in infantry, his army was more experienced, had better morale, and was better led. Both armies deployed in three horizontal lines; however, Caesar had created a reserve from his third line consisting of six cohorts.

The two armies faced each other on a narrow plain about three kilometers wide in which the Enipeus River formed the southern boundary and a string of hills the northern boundary. When the two armies deployed, they stretched from one end of the narrow valley to the other, thus making it impossible for wide flanking maneuvers.

The left wing of Pompey’s army was led by Lucius Ahenobarbus leading Italian legions, Scipio leading Syrian legions in the center, and Afranius leading Spanish and Cilician legions and 600 cavalry on the right wing. Deployed on both flanks of Scipio’s legions were Greek infantry. Various other allies, in whom Pompey had little confidence of their ability to stand firm in battle, were deployed in the rear.

On the far left, Titus Labienus, a former legate of Caesar’s who had switched sides at the outbreak of the civil war, commanded 6,100 cavalry, including Galatians, Thracians, Macedonians, Gauls, Germans, and Syrians. Behind the cavalry were positioned the archers and slingers. Pompey had designated seven cohorts to remain behind to guard the Republican camp. Clad in a red cloak signifying that he was the army commander, Pompey took up a position behind the left flank.

As for Caesar’s army, Antony commanded the left wing, Calvinus the center, and Sulla the right wing where the crack X Legion was deployed. Caesar took up a position behind the right wing in close proximity to the infantry reserve. All of Caesar’s 1,000 Gallic cavalry were deployed on the right flank.

The Battle Plans of Pompey and Caesar

Pompey planned to launch a flank attack against Caesar’s right wing with the bulk of his cavalry and missile troops. The objective of the cavalry attack was to sew panic among the infantry in Caesar’s right wing. Once that had been achieved, Pompey’s infantry was to advance and together the Republican infantry and cavalry would roll up Caesar’s right flank and push his army into the Enipeus River. By using his infantry in a subordinate role, Pompey hoped to avoid a protracted fight between the two heavy infantry forces in which his legionnaires might not prevail due to their lack of experience.

Caesar anticipated that the enemy cavalry opposite his right flank would attack first. Therefore, he placed his cavalry opposite them to hide the presence of his infantry reserve as long as possible. When the enemy cavalry attempted to circle behind his cavalry, Caesar planned to have his reserve advance in an oblique maneuver designed to stop the cavalry charge.

Caesar gave explicit instructions to his heavy infantry before the battle to fight only Italians and not waste their energy engaging the allied troops. “You need not fight against them,” Caesar said. “I ask you to engage with only Roman troops, even if the allies hang on your heels and harass you like a pack of dogs.”

As for the reserve, he told them not to throw their pila at the enemy cavalry, but instead to thrust them upward to cause as many facial and head wounds as possible. He believed the foreign cavalry were vain men who would be greatly demoralized when they saw that they risked being disfigured.

Volleys of Pila

The battle began with the advance of Caesar’s first two lines. When they came to within 200 yards of the opposing army, they halted and straightened their lines. When Pompey’s infantry failed to react to their advance, Caesar’s first two lines advanced half the distance toward the enemy and halted a second time.

Under any normal situation, Roman troops charged into battle against an enemy. They did this to gain the natural advantage that came from the shock of the charge. Thus, Caesar and his troops fully expected that they would collide with their fellow countrymen as both sides charged each other across the last 1,000 yards that separated the two mighty hosts. But this was not the case. Because he felt his infantry was outclassed by Caesar’s infantry, Pompey had instructed his legionnaires to remain on the defensive.

The order was at last given for contact, and the legionnaires in Caesar’s front rank began their charge. When they came to within 30 yards of their foe, the legionnaires halted briefly to accurately hurl their pila and then rushed forward to begin the melee. As Caesar’s men drew closer, Pompey’s men hurled their pila in response. The battle had begun. The time was 9 am.

Driving Back the Republican Cavalry

At that moment, the Republican cavalry swept forward against Caesar’s right flank, just as Caesar expected it would. Caesar’s cavalry, which was outnumbered six to one, held its position as long as possible to mask the infantry reserve behind it. The numerical advantage that the Republican cavalry enjoyed was apparent to everyone who witnessed its advance. The Republican cavalry’s front line was so long that it overlapped both flanks of Caesar’s cavalry.

Caesar had ordered his reserve to kneel as the Republican cavalry charged as a way to lower its profile and conceal its presence as

long as possible. As the Republican cavalry advanced closer to their position, Caesar’s Gallic horsemen withdrew in good order south toward the Enipeus River. Their withdrawal exposed the infantry reserve to the enemy for the first time.

The Republican cavalry, which had not fought together before, quickly became disorganized during its advance. Because he was not experienced leading cavalry into battle, Labienus was incapable of restoring order to the enormous number of cavalry squadrons under his command, and the attack he was leading floundered at the very moment it should have been dealing a crippling blow to the enemy.

As Labienus and his subordinate commanders struggled to maintain their unity, Caesar ordered a vexillum raised as a signal for the 1,650 heavy infantry in the reserve line to advance. Shouting as they advanced, the infantry reserve marched in perfect order toward the Republican cavalry. When they made contact with the first line of enemy horsemen, the reserve troops did just as they had been instructed. The legionnaires in Caesar’s reserve thrust their pila at the heads of the enemy horsemen in an effort to gouge out their eyes, puncture their throats, or cause other dreadful wounds.

When the first line of Republican cavalry was repulsed by Caesar’s disciplined reserve, it fled the field carrying with it all of the successive lines behind it. The retreating horsemen rode frantically for a hill on the opposite side of the Larissa-Pharsalus road from where the main battle was unfolding. Although they watched subsequent stages of the battle from that location, they played no further role in it.

Pompey Abandons His Army

With the Republican cavalry gone from the battlefield, the Caesarean cavalry returned to the extreme right flank of Caesar’s army. The horsemen rode around Caesar’s reserve and pursued the surviving enemy missile troops, who were speared as they tried to escape from the battlefield.

Observing the repulse of the flank attack in which he had placed all his hopes for success that day, Pompey promptly relocated from the battlefield to the relative safety of his hillside encampment. He abandoned his troops “like one distracted and beside himself, without any recollection or reflection that he was Pompey the Great,” wrote Plutarch.

Meanwhile, the contest between the main bodies of infantry continued. In an effort to even the odds in the fight against Caesar’s more experienced infantry, Pompey had committed all three of his battle lines to the fight before he left the field.

Advancing with Caesar’s X Legion, Crastinus fought that day without a shield. In his right hand Crastinus gripped his gladius, and in his left hand he wielded a so-called swagger stick that denoted his rank as a centurion.

Eager to prove himself worthy of Caesar’s praise, Crastinus was one of the first of Caesar’s infantrymen to engage the enemy. As the fighting seesawed back and forth, Crastinus switched from one spot to another, fighting with rage and fury against the enemy. However, his luck eventually ran out. A skilled legionnaire in Ahenobarbus’s wing of the Republican army parried Crastinus’s thrusts with his gladius and, using his scutum to shield the lower part of his face, made a shoulder-level thrust at Crastinus’s lower face. Crastinus was killed “fighting heroically, by a sword–thrust full in the mouth,” wrote Caesar.

The Infantry’s Slow Retreat

The fighting dragged on throughout the late morning. Because of its greater numbers, the Republican infantry was able to hold its ground. Tightly focused on their survival, Pompey’s troops failed to notice that their commander had abandoned them to their fate.

Many of those fighting on the narrow plain recognized familiar faces among the enemy. In some cases, the familiarity came from living in the same place in Italy, while in other cases it resulted from having previously served together in the Roman army. On a number of occasions up and down the battle line, a wounded or dying legionnaire called out to a familiar face on the opposing side, beseeching the person he knew to carry a last message home to a loved one. “Many sent messages home through their very slayers,” wrote Cassius Dio.

Once the Republican flank attack had been shattered, Caesar set about organizing a fresh advance by his infantry reserve and cavalry against the enemy’s left flank. Caesar issued orders to his reserve to advance east and, when it reached the enemy’s unprotected flank, to fall upon it.

Caesar’s reserve and his cavalry fell upon Pompey’s left flank with relish. In desperate fighting, they decimated the two legions under Ahenobarbus on the far left of Pompey’s line. When Caesar observed that Pompey’s entire line was beginning to waver, he ordered his uncommitted third line into battle.

The weight of all of Caesar’s veteran troops against Pompey’s untested army immediately compelled the Republican heavy infantry to begin a withdrawal from the field of battle. Aware that they faced near certain slaughter at the hands of their fellow countrymen fighting under Caesar’s bold leadership, Pompey’s infantry began a slow retreat. The intention of Pompey’s generals was to keep the army intact until it could reach the safety of its fortified camp and the surrounding hills to the north.

Making a Stand at the Camp

The first of Pompey’s infantry to leave the field altogether were his allies. With little invested personally in the battle between the two Roman factions, they cast aside their weapons and fled for the safety of Pompey’s camp. When Pompey’s allies fled the field, they left large gaps between the center under Scipio and the left and right wings under Ahenobarbus and Afranius, respectively. Caesar’s heavy infantry advanced unopposed into the gaps and began to assail Pompey’s Roman infantry on its flanks.

The pressure on Pompey’s Roman infantry, some of whom by that time were being assailed on two or even three sides, proved too much. Caesar’s generals sensed that victory was at hand. The generals rode back and forth along the battle lines exhorting their legionnaires to press the attack. Caesar and his men knew that if they allowed the Republican army to escape the battlefield intact they would be forced to fight it again. With that in mind, Caesar’s troops threw themselves forward furiously in an effort to smash Pompey’s army once and for all. To their credit, Pompey’s legionnaires did not flee the field but managed to withdraw in reasonably good order to their encampment.

Unfortunately for Pompey’s Roman infantry, it found not safety but chaos at its hillside camp. By the time the infantrymen reached that place, the sun had passed its zenith. Pompey’s troops found their tents torn apart and their baggage strewn about with all of their valuables gone. It was not Caesar’s men who had done the pillaging, but Pompey’s allies. It was a final blow to their morale. A small minority were too weary and demoralized to continue fighting, but the majority took up positions on the ramparts in anticipation of an assault on the camp by Caesar’s legionnaires.

Pompey’s troops were correct in expecting that Caesar would follow up his battlefield victory with a direct attack on their camp. Despite the scorching sun, which left troops on both sides exhausted and dehydrated, Caesar and his generals reformed the freshest parts of their army for a final assault on the enemy.

One Final Attack

The final assault began about mid-afternoon. Caesar’s missile troops fired multiple volleys at enemy soldiers manning the ramparts and wooden towers that rose up at regular intervals on the camp’s perimeter. Besides felling those on the ramparts, many of the arrows landed inside the camp where they struck those milling about.

Caesar’s heavy infantry then stormed the gates. Once inside, the legionnaires demanded the surrender of Pompey’s surviving troops. Anyone who did not surrender was put to the sword.

“What, into the very camp?” Pompey cried with dismay when he learned that Caesar had bypassed the towers and ramparts and gained entry through some of the gates. In a state of shock, Pompey changed into the garb of a common soldier and fled with a few other high-ranking officials via a secure gate. Scipio, Afranius, and Labienus also fled the camp, riding west to Dyrrachium where they boarded a ship to Africa to continue their opposition to Caesar.

Altogether, Pompey’s army had lost 15,000 men in the battle and another 24,000 captured. In contrast, Caesar lost about 1,200 killed and wounded.

Six weeks after the battle, Pompey arrived by ship on September 28 in Alexandria harbor, where he boarded a small boat that would carry him to shore. Two Romans who had served under him hacked him to death. They cut off Pompey’s head and tossed his body into the surf.

The men were acting on orders from a group of advisors to the youthful Ptolemy XIII, co-ruler of Egypt with his sister Cleopatra. The advisors had ordered Pompey murdered in hopes of courting favor for Ptolemy XIII with Caesar.

On October 2, Caesar arrived in Alexandria where he was presented with Pompey’s head and his signet ring as proof of his death. Caesar turned his head aside and cried.

Caesar would spend the next three years defeating those loyal to Pompey who contested his control of the Roman Republic. Caesar himself would be hacked to death on March 15, 44 bc, during a meeting of the Roman Senate. The Senate had chosen to meet that day in a temple attached to Pompey’s theater complex. When Caesar fell to the ground, he lay dying at the base of a statue of Pompey.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments