By Wil Deac

Andrei Andreievich Vlasov, one of Soviet dictator Josef Stalin’s favorite generals, played a key role in saving Moscow from Adolf Hitler’s armies during the winter of 1941-1942. A few months after that, the tall, gaunt general was fighting for a different cause, the overthrow of Russia’s Communist regime, with the help of Nazi Germany. How this came about is one of the lesser known stories of World War II.

The 13th and youngest son of a landholding peasant, Vlasov was born on September 1, 1900, in Lomkino near Nizhni Novgorod (now Gorky) on the Volga River east of Moscow. As a youth, he leaned toward religion and, like Stalin, entered a theological seminary to prepare for the Orthodox priesthood. His direction abruptly changed in 1917 with the outbreak of the Russian Revolution.

A Demonstrated Ability to Whip Units into Shape

During the civil war that followed the Communist seizure of power from the short-lived government of Alexander Kerensky, Vlasov was conscripted into the Red Army. He showed enough promise to become an officer at the age of 18. By the time the war ended in 1922, he was a battle-hardened veteran, having fought the anti-Communist White Army as well as other armed groups resisting the Bolsheviks. Vlasov’s climb up the Soviet ladder then reached the rung of admission to the Communist Party in 1930. His leadership abilities were clearly demonstrated after he was placed in charge of the sad-sack 11th Infantry Regiment of the 4th Turkestan Division. The regiment was soon recognized as the “best in the Kiev Military Region.”

In the fall of 1938, Vlasov, now a full colonel, was named chief of staff to the Soviet military adviser to Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek. Stalin’s policy was a dual one of supporting both Chiang against the invading Japanese and the anti-Chiang Communists of Mao Tse-tung. A grateful Chiang awarded Vlasov the Golden Order of the Dragon and a watch when the 38- year-old officer’s tour ended. Both medal and watch were confiscated by the Soviet government.

Vlasov experienced déja-vu when he was next assigned to whip into shape a discredited unit, this time the polyglot 99th Infantry Division in the Kiev Military District. Within months, the popular colonel was presented the coveted Order of Lenin and a gold watch for having the district’s best division; his boss called the 99th “the best in the army.”

Although Vlasov evinced no political views, it is not unreasonable to believe that he came to share the opinions of those who were betrayed by the Bolsheviks, especially veterans of the Russian Civil War. In the 1930s the USSR was in a turmoil. Aside from the economic and social problems exacerbated by collectivization of the farms, the country underwent the seemingly endless blood purges that included most of the Red Army’s top officers.

Shortly after 3 am on June 22, 1941, Hitler’s Wehrmacht launched its blitzkrieg across the Soviet border, advancing at a phenomenal pace. While the Red Army was fighting on its own soil against an invading army, Soviet citizens were welcoming the Germans as liberators. Indicative of the nation’s disarray under Communism, over two million Red Army troops surrendered during the first three months after the invasion. That number doubled by year’s end. Among the factors that eventually reversed this trend were self-destructive Nazi racial policies that accompanied German occupation and Stalin’s appeal to the public’s nationalism.

Vlasov was in command of the 14th Mechanized Corps of the Ukrainian Front when his sector was hit by Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt’s Army Group South. As the ill-prepared Soviet defenses crumbled, Vlasov and his men fought their way out of one encirclement after another. His aggressive fighting withdrawals earned him a trip to Moscow. There, at midnight on November 10, Vlasov had his first meeting with Stalin.

Vlasov Meets Stalin; Saves Moscow

The slender officer, dark-rimmed glasses perched on his nose, towered over the stocky 5’4” Soviet dictator, who asked Vlasov’s views on stopping the enemy forces that were advancing toward the capital. The outcome of the meeting was Vlasov’s assignment as commander of the 20th Army in the defense of Moscow. The Wehrmacht was blocked at the gates of the city and, in January 1942, the 20th Army spearheaded a successful counteroffensive. The Army’s commander was awarded the Order of the Red Banner and promoted to lieutenant general. His photograph appeared alongside those of the other “military saviors of Moscow.”

There were other indications of Stalin’s benevolence toward the general. He was presented for interview by Western reporters, one of whom called him “one of the young army commanders whose fame was rapidly growing among the people of the USSR.” Later, when he reported in at his new command as deputy commander of the Volkhov Front, it was by airplane in the company of several members of the Soviet hierarchy.

The Volkhov Front, named for the river marking the battle line nearly 300 miles northwest of Moscow, was one of the most critical of the war when it was created by the Red Army high command in December 1941. The Front consisted of two armies, the 4th and the 52nd, under Lt. Gen. K.A. Meretskov. Two more armies were being formed, the 2nd Udarnaia (Shock or Assault) and the 59th. The Front’s mission was to help break the German siege of Leningrad (now St. Petersburg). It went on the offensive on January 13, 1942, with several strikes already against it. The Germans knew the offensive was coming. They also had air superiority. Furthermore, the newly formed 2nd and 59th Armies had inadequately trained troops who were unaccustomed to fighting in forests and marshes. The two new units lacked heavy artillery and ammunition and, to top things off, Army headquarters refused Meretskov’s request for a unified command to include the 54th Army reporting to the Leningrad Front in the north. It was no wonder the Soviet advance was a slow one.

Vlasov is Given the 2nd Shock Army; Then Abandoned

This was the situation into which Vlasov was thrown when he took over the 2nd Shock Army after its commander became ill. The Army slogged doggedly forward as the spring thaw turned much of the forestland into swamps. As it advanced, its flanks became dangerously exposed. On March 18, a German pincer attack snipped through Vlasov’s lines of communication. Red Army reinforcements soon broke the encirclement, allowing the 2nd Shock to refocus its attention on its advance. On April 23, Stalin abruptly dissolved the Volkhov Front to form a group subordinated to the Leningrad Front. This, in effect, left the 2nd Shock in the approximately 50-mile-long pocket it had punched through hostile territory in a northwesterly direction from the Volkhov River toward Leningrad.

Reassigned, Meretskov stopped off in Moscow to tell Stalin, “The 2nd Shock Army is entirely played out … it can neither attack nor defend itself.” He suggested either reinforcement or withdrawal, otherwise “a catastrophe is inevitable.” Nothing was done, however, and in May Vlasov’s men were again cut off. Only on June 8 did the Soviet dictator admit he was wrong in disbanding the Volkhov Front. He ordered that the 2nd Shock be relieved, but it was too late. Although new attacks broke a 400-yard-wide passage through to the 2nd Shock, only the wounded and a handful of troops could be withdrawn before German Stuka dive-bombers and artillery scattered the exhausted Russians.

At 11 pm on June 23, the 2nd Shock made a final desperate attempt to break out of the temporary encirclement. Two small breaches were made in the German lines, allowing some men to escape. The next day, realizing his remaining troops were in a hopeless situation, Vlasov ordered them to find their way out of the trap in small groups. A last-minute Soviet attempt to rescue the general and his staff failed. By the morning of the 25th, silence had descended over the burial ground of the 2nd Shock Army.

For over two weeks, moving from one hiding place to another, Vlasov evaded the German roundup of 2nd Shock survivors. One can only imagine the hunted man’s frame of mind. He later wrote, “Is not Bolshevism the chief enemy of the Russian people? … There, in the forest and moors, I finally concluded that my duty is to call the Russian nation to struggle for the overthrow of Bolshevik power—the creation of a new Russia where every man could be happy.”

Vlasov is Captured and Flipped

German intelligence officers finally found Vlasov in a farmer’s shed on July 12. Well treated by his captors, he was interrogated before being sent to a camp for high-level prisoners in the German-occupied Ukraine. There, on August 3, he and another captured officer authored a letter to the Germans explaining how the USSR could be defeated. The letter stressed Russian patriotism, Stalin’s strength, and the necessity of harnessing the Russians themselves to beat the Communists. The Germans, it stated, should establish a Russian National Army made up of the local population and prisoners of war.

A number of German military officers and civilians sympathetic to one degree or another with Vlasov’s ideas, responded to the letter by visiting the captured general. They provided a platform from which Vlasov was able to voice his viewpoint and begin to form an organization. The Germans already were exploiting other anti-Communist Soviet citizens. These included military personnel who volunteered their services, POWs, and civilians angry at Stalin’s oppressive regime. None had the broad agenda or prestige of Vlasov, the highest ranking Red Army defector.

Unfortunately for Vlasov, his supporters were those seeking policy changes and not the Nazi policymakers. Foremost among the former was Captain Wilfred Strik-Strikfeldt. The captain, who was attached to General Reinhard Gehlen’s Fremde Heere Ost (Foreign Armies East), the intelligence organization targeted against the USSR, had lived and worked in pre-Communist Russia.

While top-level Nazis had no intention of letting Vlasov have a free hand, they saw the immense propaganda value he represented. This dichotomy in wartime Germany can be explained in the words of one historian, who wrote that the Nazi system was marked by “contradictions and multiplicity of authority.” The general, accustomed to the totally rigid Soviet system, believed that even someone of Strik-Strikfeldt’s modest rank spoke for Hitler. Vlasov’s initial optimism was gradually to give way first to confusion, then to disillusionment.

The Russkoe Osvoboditelnoe Dvizhenie

The first public act of Vlasov’s Russkoe Osvoboditelnoe Dvizhenie (ROD, Russian Liberation Movement) was a small one. It came on September 10, 1942, in the form of an anti-Stalin leaflet signed by Vlasov and directed at Red Army officers and civilian intelligentsia. The Allies initially were skeptical of its authenticity because of the general’s high standing with the Kremlin. The latter, upon realizing that Vlasov had indeed changed sides, reviled him and even unsuccessfully sent an agent to infiltrate the ROD and assassinate the general. The seriousness with which the Kremlin took the threat of Vlasov is further evident from Stalin’s comment that the renegade officer was “at the very least a large obstacle on the road to victory.”

In September 1942, Vlasov was moved to Berlin, where he conferred with other anti-Communist Russians, some of whom joined his movement. A training camp was set up in an army barracks in Dabendorf just south of Berlin. The Russian POWs and laborers—numbering over 7,000 by the end of the war—who trained there received military and political instruction to pass on to others.

Interestingly, authorization for the camp came from General Gehlen and Lt. Col. Claus Count Schenk von Stauffenberg. Gehlen was to become West Germany’s spy chief during the Cold War, while Stauffenberg tried to kill Hitler on July 20, 1944, and died for his action. During the months that followed, leaflets bearing the general’s name were dropped behind the Soviet lines to encourage desertions.

The ROD’s first major statement, published on January 13, 1943, was the Smolensk Declaration. Although originating in Berlin, it was named after the Russian city for propaganda purposes. The document limned Russian grievances against Commnist rule and stated the ROD’s principles and goals. It figuratively put the ROD on the map and created a Russkaia Osvoboditelnaia Armiia (ROA, Russian Liberation Army). Although a blue and white St. Andrew’s Cross shoulder patch was distributed to various anti-Communist Russian units, the ROA was never really an army. It was a concept created to give a sense of unity and purpose to all Eastern soldiers serving alongside the Wehrmacht. Vlasov was accepted as the ROA’s leader.

Vlasov Oversteps

Vlasov followed the declaration with a March 1943, 32-paragraph open letter titled “Why I Decided to Fight Bolshevism.” It outlined his career, explained his disillusionment with Communism, and pleaded for the Russian people to follow his example. It also included attacks on the Americans and British to placate his captors. The Soviets reacted with a barrage of anti-Vlasov propaganda. It was not only Moscow he riled, however. Allowed to visit German-occupied territory, Vlasov became too outspoken even for the Nazis.

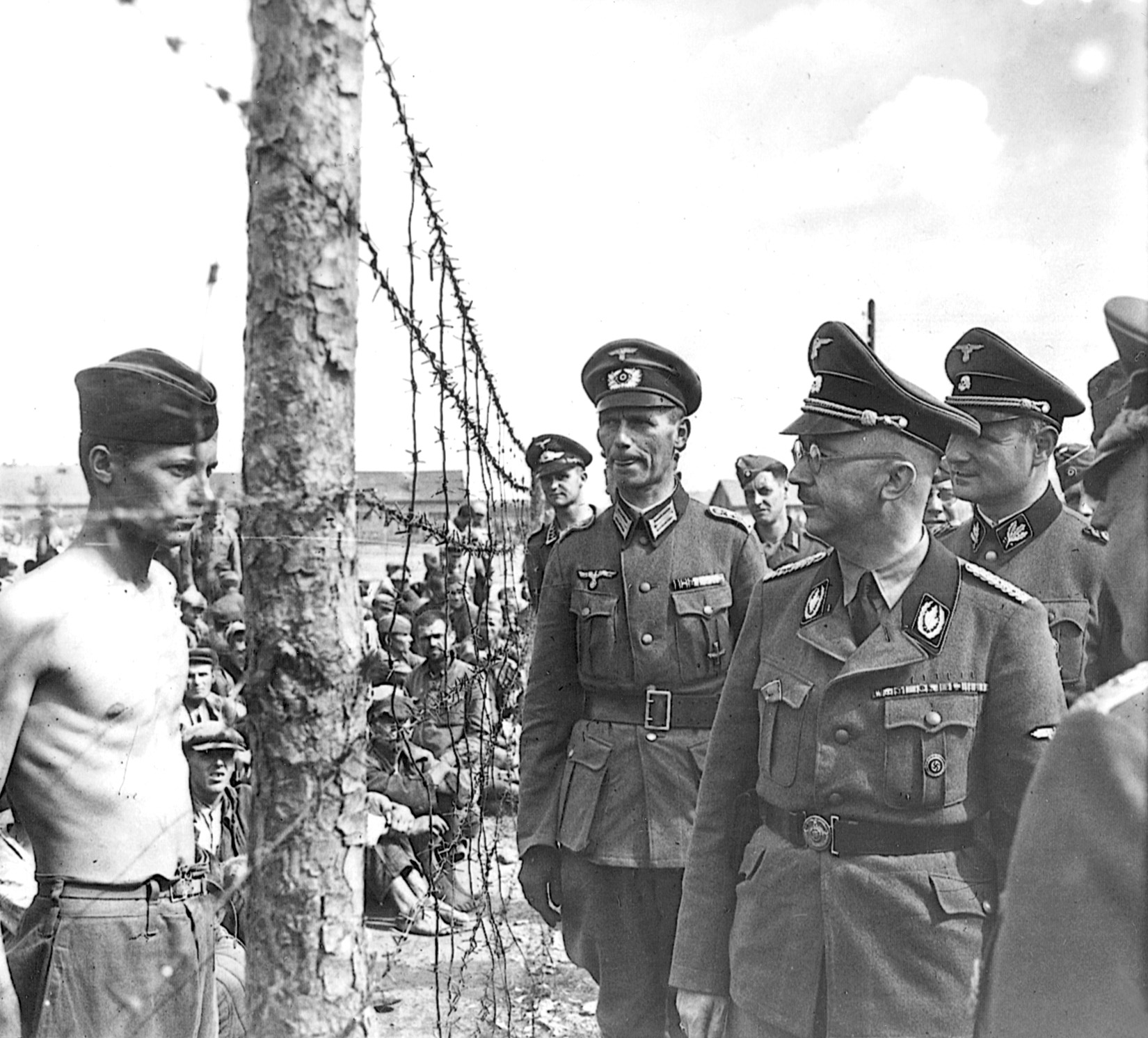

State security chief Heinrich Himmler formally complained to Martin Bormann, the Führer’s closest confidant, that Vlasov was going too far in promoting Russian nationalism. Hitler, reading Himmler’s complaint, threw one of his tantrums, demanding to know how a member of an inferior race had the right to abuse the hospitality of the Third Reich. The Führer said, “Political inferences by some of the military were erroneous” and, ignoring the thousands of Russians already attached to the Wehrmacht, that “we will never build a Russian army.”

Vlasov was placed under house arrest. It was during this low period that Vlasov, dissuaded by his backers from throwing in the towel, made low-key visits to the Dabendorf camps and trips around Germany. On one of these trips, accompanied by the ever-steadfast Strik-Strikfeldt, he met the widow of a German officer. Realizing that he would never again see his Russian wife, he eventually married the widow despite the fact that neither spoke the other’s language.

Not until the late summer of 1944 did the Nazis finally grasp the straw Vlasov had extended them two years earlier. By this time, Hitler’s empire was crumbling under the “combined blows of the Soviets and the Western Allies. On September 16, Himmler, making an about-face, told Vlasov he could form his own army.

The Komitet Osvobozhdeniia Narodov Rossi

The initial step was the Prague Manifesto of November 14. Again describing Soviet sins, it then went on to announce the establishment of the Komitet Osvobozhdeniia Narodov Rossi (KONR, Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia). The KONR’s principles and goals were laid out, all aimed at overthrowing Communism and creating a new Russia. It was a call to arms signed by Vlasov and 36 KONR full-member officers and civilians. The manifesto was made public in an elaborate ceremony followed by a gala party in the Czech capital for which it was named. Significantly, no high-level German officials attended.

If Vlasov had any doubt that he was a Don Quixote tilting at windmills, it was all too quickly dispelled. Instead of the 10 army divisions he had been promised by Himmler, he got only two. Only current POWs could join these divisions. Russians already in German uniforms, those familiar with the ROD’s principles and goals, were barred. Contrary to Vlasov’s idealistic plans, the divisions would be used solely to defend Germany.

Nazi bureaucracy and a lack of supplies were further hurdles placed in the general’s path. Within two months of the publication of the manifesto, about one million Russian POWs volunteered to join the KONR army. Even allowing that many volunteered only to get out of German camps, the number is nevertheless impressive. By February 1945, Vlasov had formed a general staff led by Maj. Gen. Fedor Trukhin. Two other generals, Sergei Bunyachenko and Georgi Zverev, were tasked with training the two divisions.

The KONR 1st Division, formed in late November 1944 in southern Germany, was composed of a hodgepodge of POWs and Russian units that had been part of the Wehrmacht. Bunyachenko was not able to get his disparate recruits into shape until the following February. That same month, to show what the KONR could do, Vlasov sent off a detachment of volunteers to the Eastern Front. Led by Colonel I. K. Sakharov, the detachment defeated units of the Red Army on the east bank of the Oder River and caused the defection of hundreds of Soviet soldiers. Bunyachenko’s division, numbering about 20,000 men, was ordered north by the Germans without Vlasov’s knowledge.

KONR Leaders Begin to Defy Nazi Orders

The Nazis had once again broken their word. The original agreement was for the two divisions to operate together directly under the general’s command. On April 6, 1945, the 1st Division was sent in against a Red Army bridgehead on the Oder River east of Berlin that the Wehrmacht had been unable to eliminate. Vlasov, again informed after the fact, had no choice but to acquiesce. Launched without air or artillery support, the KONR attack failed. After heated arguments with the Germans, Bunyachenko defied further orders and marched his men southward to western Czechoslovakia (called the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia since the German occupation), ultimately halting about 30 miles north of the Czech capital.

For a number of reasons, among them the chaotic war situation and a reluctance to fight a fully armed division, the Germans did little more than threaten and bluster. Vlasov, who had left Germany to set up temporary headquarters near Prague, met with his 1st Division commander to discuss their future.

Meanwhile, the KONR 2nd Division, now led by General Trukhin, left its encampment in southern Germany. In defiance of German orders, it moved eastward into Austria, halting at the Czech frontier south of Prague. Out of touch with Vlasov and Bunyachenko, Trukhin made contact with advance units of the U.S. Army. The Americans told the division to cross their lines and surrender within 36 hours.

Trukhin tried to get in touch with Bunyachenko to persuade him to join the 2nd Division in surrendering to the Americans. This failed when Trukhin and two other emissaries, sent separately, were captured by Czech partisans led by a Red Army officer. Trukhin was turned over to the Soviets; the others were immediately hanged. Major General M.A. Meandrov assumed command of the 2nd Division.

Shortly after the 1st Division halted outside of Prague, a group of Czechs visited Bunyachenko to ask his help in ousting the Germans occupying the capital. The Russian’s initial reluctance to agree was soon eroded by the Czech’s predicament, the strong anti-Nazi sentiment among his troops, and a desire to show the Allies that he and his men were not Hitler’s puppets. Historians disagree on Vlasov’s position at this point. One states that the general “violently” opposed turning on the Germans. Another writes that Vlasov was “quite happy for Bunyachenko to operate as he saw fit.” In any case, days later Vlasov broke completely with the Germans and fully backed his division commander.

On May 6, Vlasov’s 1st Division went into battle on the side of the Czech insurgents, who had taken to the streets two days earlier. Together, the KONR Russians and the Czechs quickly gained the upper hand over the German forces, which included an SS division dispatched to quell the uprising. The next day, an American patrol arrived and, overcoming its surprise at seeing Russians in German uniforms, asked if help was needed. The good news was that no American assistance was required. The bad news, imparted by the captain leading a patrol from the U.S. Third Army, was that U.S. and Soviet leaders had already decided that Prague was to be occupied by the Red Army.

Moreover, the Communists among the Czech insurgents, predictably emboldened, made it clear that the Vlasov forces would soon be considered enemies. Desperate to avoid capture by the Red Army, Bunyachenko’s men and the SS division they had been fighting joined forces to push their way out of an increasingly hostile Prague. The tanks of Soviet Marshal Ivan Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front entered the city on May 9, the morning after Germany’s surrender to the Allies.

Vlasov Surrenders to the Americans; Recaptured by the Soviets

That same day, Vlasov’s 1st Division and the U.S. 16th Armored Division met west of Pilsen in westernmost Czechoslovakia. The KONR troops were disarmed and placed under guard. On the morning of May 12, Vlasov learned that the Allied policy was to turn over to the Soviets all citizens of the USSR who had fled during the war. The general immediately dismissed his men; it was every man for himself.

One source estimates that half of the division’s approximately 20,000 soldiers quickly fell into the hands of the Red Army and the rest fled into the American zone. Many subsequently were repatriated to the Soviet Union where they faced imprisonment or certain death. Many committed suicide rather than return. The 2nd Division, which laid down its arms on May 6, slipped into the American lines only to be interned and turned over to the Soviets. Smaller KONR components coped as best they could on their own.

Accounts differ, but there is little question that, as the Americans in Czechoslovakia pulled back, Vlasov accompanied them in a jeep. One of the U.S. Army units had not gone far before a Red Army armored column blocked its way. Soviet officers went from one vehicle to another, peering inside. They finally found what they were looking for; either they had prior knowledge or they were lucky. Vlasov was hauled out of the jeep, placed in a red-starred vehicle, and driven eastward.

The secret trial of Vlasov, Trukhin, Bunyachenko, Meandrov, Zverev and seven other KONR officers began on July 30, 1946. They were accused of treason and carrying out “espionage, diversionary and terrorist activity against the USSR.” They were sentenced on August 1 and hanged the next day. A witness reportedly said that the method of execution was so horrible that it could not be described.

Whether one sees Andrei Vlasov as a traitor or as a hero depends primarily on how one views the Soviet dictatorship under Stalin. What is certain, as one historian pointed out, is that “Vlasov was … an idealistic man who hated the tyranny of Stalin and made the mistake of seeing the Germans as potential liberators.”

Wil Deac is a military history writer based in Washington, DC. He is the author of Road to the Killing Fields, the story of Cambodia’s war of 1970-1975.

NOBODY saw nazis as liberators except western ukranians.

You are correct. The proper wording is “hope for”, in vain, of course.

I’m new to this site. I found it by researching Vlasow after buying a WWII photo of him which led me here during some research. . I read the article and found it interesting. I think that Vlasow suffered from ADHD. He was bouncing all over the place. I don’t think he was very smart nor did he grasp the differences between Hilter and Stalin. Personally, I think he made huge mistakes in his judgement. Maybe he was trying to pick the lessor of two evils. He should have begged the Americans to hide him. How much history did he take to his grave? Did the Americans have the power to refuse to turn over Vlasow?