By David H. Lippman

“This is the shortest day,” General Dwight D. Eisenhower, supreme commander of Allied forces in Western Europe, wrote in his diary for December 21, 1944. “How I pray that it may, by some miracle, mark the beginning of improved weather!”

His fervent prayer was a reflection of the desperate situation in which the Allies found themselves as winter began in 1944. On December 16, Adolf Hitler had hurled two mighty panzer armies against the thinly held Ardennes sector, advancing against determined but thin opposition. By the 21st, the key Belgian crossroads town of Bastogne was surrounded in the south, St. Vith in the north nearly so, and General Hasso von Manteuffel’s 5th Panzer Army was closing in on the Meuse River at Dinant.

Relying on Good Weather

Two things were needed to stop the last-ditch Nazi attack: hard counterattacks and clear weather to enable the overwhelming Anglo-American air forces to operate against the German supply and communication lines.

So far, neither was forthcoming. The Germans had the Allies off balance. Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr., was set to attack on December 22, but the entire Ardennes sector was covered with thickly overcast skies, hanging mists, ground fog, and snowstorms, preventing the vast Allied air arm from operating.

The Allies had plenty of planes. The Ninth U.S. Army Air Force boasted 1,111 medium bombers, 1,502 fighters, and 217 reconnaissance planes. The British 2nd Tactical Air Force was somewhat smaller, with 293 medium bombers, 999 fighters, and 194 reconnaissance planes. Behind that, the Allies could call on the heavyweights of the U.S. Eighth Army Air Force, with its 2,170 heavy bombers and 1,234 fighters, and the Royal Air Force Bomber Command’s 1,871 heavy bombers. It all added up to 9,720 aircraft, and all were socked in by heavy weather.

The Allied aircraft and their pilots were an elite force by now, many of the pilots veterans of bitter fighting over France and Germany. Their aircraft were the most up-to-date technology British and American factories could provide—Supermarine Spitfire and North American P-51 Mustang fighters for top cover, powered by Packard-built Merlin engines; twin-boomed Lockheed P-38 Lightnings and the rugged Republic P-47 Thunderbolt for fighter and ground attack missions; and Hawker Typhoons armed with antitank rockets. It was a highly formidable, mobile, well-trained force, probably the world’s most powerful air force at the time.

But it was only good if it could fly, and on December 21, 1944, it could not. And never was it more desperately needed. Patton was about to counterattack—he had ordered his chief chaplain, Father James O’Neill, to pray for good weather—and so was Lt. Gen. J. Lawton Collins and his powerful VII Corps on the northern flank. But Bastogne was short on ammunition and medical supplies, and the situation at St. Vith was so desperate the Americans were preparing to pull out.

“This is our big chance,” wrote Brig. Gen. Dick Nugent, who commanded the 29th Tactical Air Command. “Several days of good weather for air action followed by a heavy, well-placed counteroffensive should end the war.”

Fog, Mist, and Snow

Nugent did not get what he wanted. The morning of December 22 began with a snowstorm over the Ardennes. At Ninth Air Force’s daily weather briefing, Major S.S. Tomlin, the Air G-3, gave a gloomy report on the situation to General Hoyt Vandenberg, who commanded the Ninth Air Force. Without air cover, the German offensive would continue. Colonel George F. McGuire followed, listing the planned air strikes for the next two days—assuming the weather broke. Finally, Major Stuart J. Fuller gave the weather report. Fog, mist, and snow. Outside the Luxembourg headquarters, the airmen could hear the sounds of infantry trudging through the snow toward the front. Vandenberg tried to relieve the tension with humor, saying, “Do you think that Hitler makes this stuff?”

It broke the tension, if not the fog, but Vandenberg called in Fuller for a one-on-one. “How much longer is this going to last?” Vandenberg asked his weatherman.

Fuller said that stagnant high pressure systems existed to both the east and west of the Ardennes—nothing was going to start them moving. Maybe on the 26th. Four days away.

“Suppose it’s clear tomorrow,” Vandenberg asked rhetorically. “What are you going to do?”

Fuller turned away and muttered, “Shoot myself,” under his breath.

That day was a tough one for the Allied defenders in the Ardennes. A team of German emissaries approached a position held by the 101st Airborne Division, demanding that the besieged Americans in Bastogne surrender. Brig. Gen. Anthony McCauliffe gave the Germans a legendary one-word response—“Nuts”—but the siege continued. At Ninth Air Force headquarters, the planners worked on ideas for attacks that hinged on good flying weather.

“It’s Almost Certain We’ll Fly Tomorrow”

The aviators and their ground crews may not have been flying, but they felt the pressure. The 430th Squadron of the 47th Fighter Group, a unit of P-38s, was less than 30 miles from advancing German armor. At 8 pm on the 22nd, the squadron was warned that they would defend their airfield at all costs. Guards were posted, and “everyone went around armed to the teeth,” wrote a night fighter pilot. “It was a wonder no one was shot.”

Pilots were told to be ready to evacuate, and enlisted men were briefed on standard infantry tactics. Then came the word that the Germans were not that close—but everyone was still scared and frustrated. Unable to fly, pilots wondered if the airfields would be overrun by the Germans before the weather cleared.

Some aviators worried about personal fears. Lieutenant John C. Calhoun wrote his mother and let her know that he had made out his full allotment of his GI insurance to the family. “I have done my best to provide for you in case I do not come home, a possibility we must all face together the way fighting is going over here for us airmen,” he wrote.

At the Ninth Air Force weather center, Major Fuller was back on duty amid external and internal gloom. But, a little after midnight, in came a report that boosted morale. It showed that in the east the barometric pressure was rising.

General Sam Anderson, who commanded the 9th Bombardment Division of Ninth Air Force, was asleep in his quarters in Rheims, France, when his phone rang just after midnight. It was Anderson’s weather officer.

“General, you won’t believe this, but it is going to be clear tomorrow,” said the weatherman. Anderson thought he was dreaming. He rose from his bed and peered out the window into the fog. “I can’t see across the street,” Anderson told the weatherman.

The lieutenant explained the sudden rise in barometric pressure moving in from the east. Anderson was convinced and rang up Vandenberg’s headquarters in Luxembourg.

Their weather team was on the ball, though. Fuller and his crew studied the fresh data coming from remote stations near the front line. The heavy overcast and fog were breaking. What was coming was a “Russian high” from the east, which would push aside the fog and low clouds, replacing them with colder air and clear skies.

“Notify the general,” said a senior officer. “Tell everybody that it’s almost certain we’ll fly tomorrow.”

“What a Glorious Day For Killing Germans!”

Vandenberg wasted no time. He woke up his staff officers, and they began cutting orders over teleprinters to air bases in England, Holland, Belgium, and France to be ready to attack.

The weather was breaking. Even the Germans noticed it. A Russian high was indeed pushing through westward across the Ardennes. It cleared over the Luftwaffe’s bases first, of course, and the Germans reacted immediately. The 2nd Jagdkorps warned its scattered fighters, bombers, and antiaircraft gunners: “The weather in the morning will probably bring relief to us and difficulties to the enemy. In the afternoon the enemy will be able to fly. All forces are to be made ready, so as to be able to successfully engage in an air battle on a grand scale. Four-engined bombers are the Army’s greatest danger. All formations will therefore direct their ruthless attacks on them.”

As the sun rose over the Ardennes on Monday, December 23, it burned through the fog and mist, replacing the gray with clear blue. A GI on the ground called it “the war’s most beautiful sunrise.” Patton remarked wryly, “What a glorious day for killing Germans!”

Shortly after dawn, the Eighth Air Force’s massive Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses and Consolidated B-24 Liberators began thundering down airfields in England’s Lincolnshire to attack German communication targets east of the battlefield. The RAF’s Bomber Command began planning a massive night raid on Cologne and its rail centers.

Allied Air on the Offensive

At daybreak, the Ninth Air Force and 2nd Tactical Air Force took to the skies of Europe. Everywhere weary GIs and British Tommies looked to the sky to see flocks of metallic starlings headed east—American P-47s and Martin B-26 Marauder medium bombers, British Hawker Tempest ground attack planes and De Havilland Mosquito fighter bombers—roaring along in loose four-plane formations, top cover fighters weaving between them.

The Ninth Air Force made 696 fighterbomber sorties, but the 19th Tactical Air Command had all seven groups active in 451 sorties, bombers loaded with fragmentation weapons and a new device, napalm, a deadly chemical jelly created by DuPont, that set targets aflame.

Soon the American airmen were in action. The 36th and 373rd Fighter Groups hit the Luftwaffe’s air bases at Bonn-Hangelar and Wahn, where the Germans were revving up their Focke-Wulf FW-190 fighter bombers for their own missions. The Americans bombed and strafed the hangars and buildings, blasting nine planes on the ground. The Luftwaffe hit back immediately, with 60 German planes attacking. The 36th and 373rd Fighter Group’s P-47s clawed back, shooting down three fighters.

At Bonn-Hangelar, 30 FW-190s and Me-109s charged the Americans during the bombing and strafing, making accurate damage counts on the ground impossible. The Germans lost 14 fighters and the Americans seven in the pitched battle. The German defenders in the air, seeing that their two bases were out of action, had to find alternative landing grounds—at least one was heard to crash.

The 9th Tactical Air Command flew 211 sorties in 19 missions and dropped 64 tons of ordnance, claiming 42 German aircraft for the loss of five Americans. Tactical reconnaissance planes spotted heavy German motor traffic in the German rear, bringing up supplies to the frontline troops.

The British were active, too. Rocket-firing Typhoons of 83 Group attacked the 1st SS Panzer Division, whose Panther tanks were struggling toward the Meuse. An intercepted radio message on January 1 noted an observation by a 1st SS Panzer Division officer that a single direct rocket hit on a Panther tank meant a total loss.

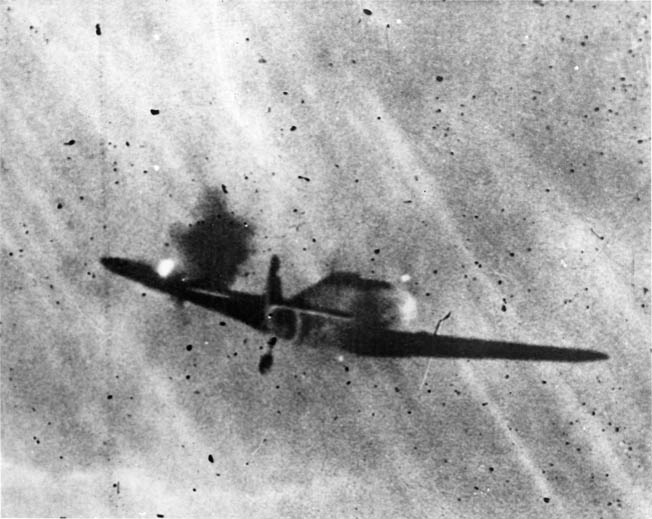

American medium bombers pounded rail bridges over the Rhine River, seeking to cut supply traffic in the rear. But the Luftwaffe was up in the clear skies, too. Southeast of the city of Euskirchen and its train yards, two dozen Me-109s bounced into the B-26 Marauders. Covering P-38s swooped down on the Me-109s, shooting down 11 of the enemy for the loss of one.

That afternoon, another fighter group missed its rendezvous with bombers but did find four FW-190s, shooting down three of them for no loss.

And so it went all day over the Ardennes, one-sided air battles. The 368th Fighter Group claimed 13 enemy fighters. Another group of P-47s shot down 15 German planes for the loss of one pilot.

There were good reasons for the overwhelming victories. Most of the Luftwaffe’s best pilots were dead or in prison camps after six long years of war. The Germans did not rotate their pilots in and out of tours of duty as the British and Americans did. New pilots were not as well trained as the veterans who had covered the invasions of France and Russia. And the British and Americans practiced well-coordinated tactics.

P-38s Halting the Panzer Tide

While the fighters were engaging in dogfights over the Rhineland, the critical air battles were raging over the Ardennes. Nothing was more important than slowing down the relentless panzer tide, and the two P-38 groups at Florennes were sent after Manteuffel’s lead outfit, the 2nd Panzer Division, streaking for Dinant, the Meuse River, and the fighter pilots’ own base. All night long ground crew at Florennes could hear and see the distant boom and flashes of heavy artillery to the east. At dawn, it was cold but clear. Mechanics got the P-38s ready. The 474th was one of the last groups to operate the massive twin-engined fighter, and despite their effectiveness as tank killers they were maintenance headaches.

In the cold, pilots walked out to their waiting aircraft. Ground crews pulled out chocks, and the P-38s rumbled down the runway and into action.

Once airborne, the 474th flew nine separate missions against the enemy. One flight hit a column belonging to the German 89th Infantry Division just west of Rocherath. The ragtag group of a depleted company was marching along in dispersed order when six P-38s hit them at 5 pm. Eight of the 50 Germans were killed and another 12 wounded.

Not every attack went well. Another flight of four P-38s spotted a concentration of German vehicles from the 9th SS Panzer Division near Vielsalm. Major Ernest Nuckols reported a “juicy convoy of possibly 200 vehicles” and swooped in. Then his bomb refused to drop. The rest of the flight returned with little better result. A second strike on the 9th SS Panzer Division met with heavy flak, which damaged planes. Lieutenant Adrian Knox was hit by flak fire and parachuted out of his plane. Only after the war did his pals learn that he was killed.

But the big story for the 474th was the German spearhead near Dinant. The attacks were all-out, and even a P-61 night fighter was committed on a rare day mission. The objectives were the roads between St. Hubert and Marche, and 2nd Panzer Division’s vehicles were all over them.

At noon the supply column of the 3rd Battalion, 766th Volks Artillery Corps, moved into the village of Foy Notre Dame, less than five miles from the Meuse. Soon after the Germans arrived, so did the 474th and its P-38s. The dreaded “Jabos” swooped down on the column and immediately burned six trucks and three half-tracks, exploding the battalion’s only fuel truck, wiping out 3,400 liters of gasoline. The 2nd Panzer Division was soon out of gas.

P-47s Over Bastogne

The P-47s of the 406th Fighter Group had a busy day, too, based at Mourmelon-le-Grand some 80 miles from the Bastogne battlefield. The 406th had enjoyed friendship with the base’s other tenants, the famed 101st Airborne Division, now besieged in Bastogne. The 406th regularly traded its ample supplies of whisky to the paratroopers in return for souvenir Nazi Luger pistols. Now the 406th learned that their pals were surrounded at Bastogne and needed help.

Private Henry Mark Connell lashed fragmentation bombs and napalm under the wings of the Thunderbolts out on the freezing runways in slush, wind, and snow. Armed guards covered the approaches to the field, watching for German paratroopers. Conditions were rugged. The miserable wood huts were heated by coal stoves that were hard to start. Someone discovered that the fast way to start a coal stove was to add a little napalm to the ash pans—that brought out a quick fire.

At dawn on the 23rd, the 406th’s immense P-47s thundered down the runways. In less than half an hour, the P-47s were over the battlefield. Among their pilots was Lieutenant Howard W. Park, a veteran tank buster from Normandy, in his red-nosed Thunderbolt named Big Ass Bird II.

From 12,000 feet, he flew into a high-speed dive against a convoy of tanks, troops, and guns and immediately came under fire from mobile German 20mm flak guns deployed around Bastogne. “I remember so vividly my slipping and skidding as streams of flak fire reached for me, sometimes within three feet of my wing surfaces. Despite skill, a lot of luck was needed to escape unscathed. The flak took a toll. It seemed as if the 513th was always first out and it seemed we lost one in four in lead flight every time. Actually we lost five of the 513th in three days, and seven in a week during which the group lost a total of 10 pilots. Most of those who didn’t return were recently transferred to us from the States and had no feel for the flak as those of us who dealt with it regularly,” Park wrote.

The P-47s ranged over the Bastogne area, spotting tanks disguised as haystacks. To the north, American P-47s hammered Germans gathering at the Baraque de Fraiture crossroads for an attack, forcing the 2nd SS Panzer Division to postpone its attack until the American aircraft had gone home, giving the defenders time to prepare.

East of Trier, more P-47s of 514th Squadron under Captain Bedford R. Underwood met up with 20 Me-109s and claimed six of those for the loss of two of their own.

Captain Bernard J. Sledzick gave this account: “Ten of the enemy fighters went down on the four that were attacking the target, leaving two Me-109s to attack Lt. Fuller and me. I maneuvered my plane onto the tail of one of them, fired and saw strikes on him which caused a fire, but the fire went out although the plane was smoking badly. I gave him another burst and the pilot bailed out. In the meantime, the second Me-109 had gotten on my tail and Lt. Fuller promptly disposed of it. I saw two tracers hit the Me-109 and it exploded in the air … below us the aerial battle was raging. Every time we saw an Me-109 on the tail of a P-47 we dove down on it causing it to break away. Lt. Jones received a hit in the cockpit and three of his toes were blown off by a 20mm burst. Lt. McLane and Lt. Price were shot down and both bailed out. Lt. Sickling shot down three Me-109s before the aerial battle. Lt. Jones made it back to Mourmelon and crashed on landing due to his injuries…. Lt. McLane bailed out over enemy territory and became a prisoner of war…. It seemed like the battle only lasted a few minutes and parachutes of downed pilots filled the sky.”

The accurate shooting was aided by Captain James Parker—an air control officer in Bastogne who was finally demonstrating his value after days of cloud cover and uselessness— who radioed instructions to the attacking planes. He sent some of the P-47s west where German troops were reportedly congregating for a major attack. As the P-47s swooped in, they saw tank tracks leading into the woods. Napalm set the trees on fire, and the planes moved in to strafe the exposed enemy. By day’s end, almost every German-occupied village around Bastogne was smoking. The 406th claimed 97 vehicles, 11 tanks, 20 horse-drawn vehicles, and 24 gun positions. The count was probably exaggerated, but the damage was not—the Germans postponed their attacks until night.

Inside Bastogne, Colonel William L. Roberts, who commanded Combat Command B of the 10th Armored Division, McAuliffe’s tank force, said the American fighter bombers were worth “two or three infantry divisions.” Parker, who had been all but ignored during the bad flying weather, earned a Bronze Star.

Air Reconnaissance Under Fire

Bombers and fighters were not the only planes sortied that day. The 363rd Tactical Reconnaissance Group flew into action in the Ansbach-Koblenz area, hunting for German trains and road convoys. Enemy fire was intense. Two P-38s were attacked by a German FW-190. The plane made two firing passes, and one P-38 pilot managed to turn inside to fire quick bursts into the enemy aircraft. The bullets killed the pilot, and the plane went into a lazy spiral before smashing into the ground.

The casualties were not all caused by Germans. Seven red-tailed P-47s bounced two P-51s of the 10th Photographic Reconnaissance Group, and only the superior aerobatics of the pilots saved the P-51s. Misidentification of Mustangs was common since the P-51 had a silhouette similar to the German Messerschmitt Me-109.

After a lot of radio complaining, the snafu was resolved, but one plane’s glycol tank was holed. The engine seized, and the pilot had to bail out. After hitting the frozen ground and stowing his chute, he saw soldiers heading toward him, blazing away with M-1 rifles. He quickly hid behind some rocks and screamed that he was American. The bullets flew on. The GIs, from the 4th Infantry Division, had heard about English-speaking German infiltrators and were taking no chances. So the pilot unleashed a blistering stream of obscenities. “No German could have known some of those colloquialisms,” he said later.

Operation Repulse

The biggest mission of the day was Operation Repulse, the resupply of the defenders of Bastogne. As soon as they got the word of clear weather, the 490th Quartermaster Unit began packing parachutes and supply canisters at its base in England. Some 82 P-47s of four fighter groups escorted 241 C-47 transports from the 9th Troop Carrier Command over the garrison, delivering 192 tons of ammunition, 12 tons of gasoline, and 35 tons of provisions and medical supplies to a drop zone marked by red smoke. Seven C-47s were lost to enemy flak guns ringing the town. To the paratroopers below, the drop was well-timed manna from heaven.

The 101st Airborne was not the only outfit that got airborne resupply. Another attempt was made to a group of American tankers of the 3rd Armored Division trapped behind enemy lines north of La Roche along the Ourthe River. This 1,000-man group, Task Force Hogan, named for its boss, Lt. Col. Sam Hogan, was to receive 4,000 gallons of gasoline, rations, and ammo from 30 C-47s, but they missed the drop zone and dropped them into German hands just beyond the American reach. Next evening, the Americans abandoned their equipment to escape German encirclement in the dark.

Back at Bastogne, the last C-47s were pulling out, and the fighter escorts hung around, splattering the Germans around the town with bombs and machine-gun fire. Captain Parker directed the P-47s with great precision. A report of enemy armor from an outpost was followed within minutes by a covey of P-47s to hit the German tanks. “This is better hunting than the Falaise Pocket,” one fighter pilot radioed. “And that was the best I ever expected to see.”

“Bogeys on the Deck and Going East”

Other P-47s were hard at work. After their resupply mission, the 362nd Fighter Group, also known as Mogin’s Maulers, flew 107 ground attack sorties. The 377th Squadron attacked the German Seventh Army’s key bridge at Echternach with rockets and napalm as well as bridges at Bollendorf and Vianden, missing the bridges but setting five German vehicles aflame.

Over Bastogne, the 379th Squadron spotted some 45 troop-laden vehicles heading north on the road between Recogne and St. Hubert. As soon as the P-47s swooped in, the Germans abandoned their vehicles. The same squadron also hit a tank-truck convoy between Houffalize and Bourcy.

The 378th dropped napalm and bombs on Bourcy, claiming 84 motor vehicles and 12 tanks. The air bombardment was so harsh that the 26th Volksgrenadier Division had to cancel a planned attack on the 101st Airborne. The commander of the German 5th Parachute Division had a harsh and telling comment on American air strikes: “At night, one could see from Bastogne back to the Westwall, a single torchlight procession of burning vehicles.”

The attacks at Bastogne continued: 354th Fighter Group sent the tough Panzer Lehr Division’s tanks scurrying for cover.

Other divisions benefited from the P-47s. The 84th Infantry Division was nearly surrounded, and P-47s of the 354th stormed in, hitting tanks and trucks near Forrieres, the 356th doing the same to 10 tanks and 20 trucks near Nassogne.

The legendary P-51s were up as well. The Yellowjackets of the 361st Fighter Group flew numerous fighter sweeps on the 23rd. So did their buddies in the 375th.

At 2:30 pm, several P-51s of the 375th spotted two “bogeys on the deck and going east” near Bonn. Lieutenant Caleb J. Layton and Lieutenant William H. Street dove on the enemy, and Layton sent one FW-190 crashing into the woods. Layton then attacked a second FW-190 and set it on fire. Then he saw a third plane, an Me-109, and later reported: “I got on the tail of the 109 and followed him around the hills and gullies, firing short bursts at 200 yards and observing some strikes. After turning around one of the hills, the 109 pulled up. I fired a 10-second burst at 100 yards, 0 degrees deflection, and saw strikes all over his fuselage and wings. The 109 caught fire and went into a sharp turn to the right and crashed into the top of one of the hills.”

“In the Entire Army Area, Heavy Enemy Air Activity”

The heavy bombers were in action, too. East of the Ardennes, more than 1,000 medium bombers of the Ninth Air Force and Bomber Command hammered rail centers, roads, bridges, and other choke points. Some 485 Avro Lancaster bombers pounded transportation centers near Trier, while the British 2nd Tactical Air Force ripped road targets between Malmedy and St. Vith and rail targets at Kall and Gemund.

The other big punch was the 423 heavy bombers of the Eighth Air Force, heading for the marshaling yards in the German rear. Their job was to smash the rail lines that were feeding Hitler’s offensive. The Americans dropped 1,131 tons of explosives on the rail yards at Ehrang, Junkerath, Ahrweiler, Dahlem,

Kaiserslautern, and Homburg. Some 632 fighters provided escort, fending off the Germans. The Luftwaffe tried to hit back, but shot down only one bomber and seven fighters for a loss of 69 German fighters. The veteran American 56th Fighter Group alone took care of 32 German aircraft.

The 9th Bombardment Division was also busy, with Hoyt Vandenberg’s 624 medium bombers. With so many missions, there was not enough fighter escort for the mediums, but 465 of the bombers punched through the German defenses to drop 899 tons of bombs on railroad bridges at Mayen, Euskirchen, Eller, the Kyllburg railhead, and the Prum marshaling yards. The bombing had impact. A POW captured later told his American interrogators that the damage at Kyllburg was so great that it took two hours on Christmas Day for him and his pals to get through the wreckage.

“In the entire army area, heavy enemy air activity,” read the entry in the German 66th Corps diary that day from its positions near St. Vith. “Fighter bomber attacks on German attack spearheads as well as bomb drops from four-engined bombers on roads and traffic in the area.”

Allied Bombers Meet Axis Fighters

The battle did not go entirely the Allied way. At Ahrweiler, the 391st Bombardment Group was unable to hook up with its fighter escort and attacked anyway amid weather so poor that the B-26s of the second box had to make two bomb runs, doing so through a wall of flak. Then a red-colored flare burst amid the formation and the flak stopped. It was the signal that the Luftwaffe’s fighters had arrived, and 60 FW-190s and Me-109s stormed in at 11:55 am. They attacked for 23 minutes in waves four deep and 16 abreast. German planes were everywhere—the group’s gunners reported 69 separate engagements. Sixteen of the 30 B-26s were shot down. The Americans shot down seven of the enemy.

In one action, Captain Edward M. Jennsen led a box of Marauders behind their pathfinder through heavy flak. The pathfinder was crippled and forced to turn back. Jennsen led his planes to the rendezvous point to meet their fighter escort, but none appeared. He led his group to the Ahrweiler target and ran into heavy flak and fighters. Jennsen’s Marauder was hit while dropping its bombs, and five of his other planes careened out of the sky emitting trails of black smoke.

Other bomb groups ran smack into German fighters. The 322nd Bombardment Group was hit by 50 German fighters and lost two bombers. The 387th lost four bombers and a pathfinder to 20 German fighters between Bastogne and their target at Daun.

The bombers and their crews were determined to get through, though. The 397th aimed for a railroad bridge at Eller and met up with heavy flak. Three B-26s were damaged by flak and crumpled to earth. After completing the bomb run, they were attacked by two dozen Me-109s that downed seven more bombers, leaving only five undamaged.

Sergeant Neil McGinnis watched the B-26s in the box ahead of him fly in when a German fighter appeared from nowhere and drilled bullets into a B-26 in the lead box. The B-26’s tail gunner fired back at the German, and both were shot down, plunging with their crews to their deaths.

Air Battle Over Euskirchen

At Euskirchen, a tremendous air battle erupted as the 322nd Bomb Group, Nye’s Annihilators, flew in covered by the P-38s of the 392nd Fighter Squadron. In eight minutes, the Americans lost two planes and 22 more were damaged. The lead pathfinder plane was knocked out, another’s wing caught fire and it spun out in flames, a third was so damaged by flak that its crew had to bail out near Sedan. The P-38s shot down four German fighters for the loss of one P-38. The bombardment mission had value. Captured German POWs said the city of Euskirchen was “one field of bomb craters.”

The new Douglas A-26 Invader attack planes made an appearance, too, assigned to a highway bridge near Trier, but eight of the flights failed to recognize the bridge. The rest hit the bridge accurately, and the only loss was an A-20K Pathfinder.

The 391st Bombardment Group did better with a concentrated attack on the German road center of Neuerburg, dropping 37 tons of bombs without loss. The 391st’s firm discipline earned it a Presidential Unit Citation.

More B-26s attacked Prum, east of St. Vith, trying to jam roads and blast troop concentrations. The 387th lost only one plane to flak damage—hit just before the bomb run and flipping over on its back. The pilot managed to roll over and drop his bombs before the B-26 spun out and crashed.

Mishaps and Losses

There were also some terrible mix-ups. Six B-26s of the 322nd mistook the American-held town of Malmedy for the German-held town of Zuplich and set it afire. Worse, the flames attracted more lost American bombers. For three days, the Americans pounded the town with friendly fire, killing 125 civilians and 37 American soldiers of the 30th Infantry Division, which added insult to injury—the Ninth Air Force had hammered the 30th Infantry Division in Normandy also by mistake. Disgusted Old Hickory men named the Ninth the American Luftwaffe.

There were other mistakes as five lost American bombers attacked the U.S. rail marshaling yards at Arlon, exploding five tank cars full of gasoline for Patton’s Third Army. Another attack fell by mistake on the town of Verviers east of Spa, in firm American hands. An irate General Anderson issued a stern warning that all secondary targets were to be positively identified before attacking.

The 9th Bombardment Division lost a total of 35 medium bombers, three pathfinders, and one light bomber. Four others crashed, two crash-landed, and 182 of the participating planes were damaged, many total write-offs. The losses were a shocking 8 percent of the American planes. The primary reason was the failure of bombers to hook up with their fighter escort. Anderson was dismayed by the failures, and Colonel Ed Chickering, who commanded the 367th Fighter Group, ordered the creation of a direct phone line between his outfit and the bombers to better coordinate escort missions.

Despite the heavy losses, the 9th Bombardment Division had lived up to its motto: “Smash the Enemy Until He Quits.” The bridges had been pounded. Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, the overall commander of the German Western Front, passed judgment on the bridge attacks, saying, “The consequences were disastrous. It meant that we could not get supplies or troops forward. The further we advanced the further the troops had to march … the deep penetration of heavy bombers east of the Rhine against our communications … were painful for moving our troops, our supplies and our gas…. On the roads our convoys or single motor transport could not move during the day. We could never count on when a certain division would arrive at its destination.”

Anderson was worried about the losses, though. The Luftwaffe was proving troublesome, and it would have to be punched out. That would be the Eighth Air Force’s job for the morrow.

Schilling’s Five Kills

But on the 23rd, the Mighty Eighth was sending 417 heavy bombers to the marshaling yards west of the Rhine, which were feeding the German onslaught. The bombers hit railheads southeast of the German salient at Homburg, Kaiserslautern, and Ehrang, along with three road junctions, Junkerath, Dahlem, and Ahrweiler. Some 56 P-47s from the 56th Fighter Group flew in from Boxted in England, looking for enemy fighters. They did not find any on three attempts, but on the fourth Lt. Col. David C. Schilling, the group’s boss, personally spotted a big swarm of German planes over Euskirchen airfield. He maneuvered his group behind the enemy and jumped them from the east, coming at them like another squadron of German fighters. Schilling and company were almost on top of the Germans before they were recognized.

The defenders numbered more than 90 fighters from four groups, and a wild 45-minute dogfight raged from 28,000 feet to the deck. Schilling “flew straight ahead, pulled up, applied full power, and made a slow diving turn to the left to position my flight on the outside and allow the other three to cross over inside so that we might bring as many planes into position to fire as possible. In so doing I managed to hit the rear right Me-109 with about a 20-degree deflection shot at a range of 700 yards. There was a large concentration of strikes all over the left side of the fuselage, and he fell off to the left. I then picked out another more or less ahead of the first and fired immediately. By this time the first Me-109 was slightly ahead, below and to the left, at which point he started to smoke and caught fire. I then picked another and fired at about 1,000 yards and missed as he broke right and started to dive for the deck. At about 17,000 feet I had closed to about 500 yards and fired, resulting in a heavy concentration of strikes, and the pilot bailed out.”

Separated from the other three flights of his unit, Schilling heard one of his pals in a “hell of a fight and called to get his position. As I was attempting to locate him, I sighted another gaggle of 35-40 FW-190s 1,000 feet below circling to the left. I repeated the same tactics as before and attacked one from 500 yards’ range and slightly above and to the left. The plane immediately began to burn, spinning off to the left. I then fired at a second and got two or three strikes. He immediately took violent evasive action, and it took me several minutes of maneuvering until I managed to get into a position to fire. I fired from above and to the left, forcing me to pull through him and fire as he went out of sight over the cowling. I gave about a five-second burst and began getting strikes all over him. The pilot immediately bailed out and the ship spun down to the left, smoking and burning, until it blew up at about 15,000 feet.”

Schilling had clobbered five planes in a single action. Some of his wingmates did well, too, with Captain Felix Williamson and his wingman punching out two Me-109s. Lieutenant Robert E. Winters of the 62nd shot up an Me-109 and set it ablaze. As he closed in, the Me-109 pilot cut his throttle and Winters shot ahead, ramming into the wing of the enemy plane. Amazingly, Winters recovered, but he never found out what happened to the German.

“Those Jerries Were Really Aggressive and Good, Hot Pilots”

While Schilling and his mates tore into enemy fighters below, the 61st Squadron circled overhead. Captain Joseph Perry saw a P-47 with two FW-190s on its tail, so Perry swooped in to help. He found himself amid a beehive of German fighters, but Perry shot one down quickly. Aware he was temporarily outnumbered, Perry and his wingman hit their throttles and flew into the sun, hoping the Germans would not follow. They did not. Another P-47 joined Perry and his squadron mates, and the three saw a loose FW-190 diving into the dogfight. Perry charged down and forced the FW-190 to ground level, making him prey for American light flak at 500 feet.

Other pilots were less lucky. Lieutenant Lewis R. Brown scored hits on two FW-190s, using up most of his ammunition. Then bullets slammed into Brown’s instrument panel, shattering his canopy. Brown saw an FW-190 on his tail, firing away. Brown bailed out and landed in enemy hands. The next stop was a POW camp. But when he was liberated, Brown was able to claim three of the FW-190s shot down that day.

The 63rd Squadron did pretty well, slamming into a gaggle of German planes. Major Harold Comstock, who commanded the squadron, found himself face to face with an FW-190 just 1,000 yards away. The FW-190 fired first, but Comstock’s bullets tore up the plane’s engines. The German pilot bailed out. Comstock then pulled up and clawed at an FW-190 from underneath, at nearly point-blank range. The German plane was shattered, and it disintegrated in front of Comstock.

Lieutenant Randel L. Murphy, in the same squadron, flew a P-47 named The Brat, which was unable to catch up with one of the speedy FW-190s. He spotted a P-47 in trouble and swooped down on the aggressor FW-190, scoring hits all along the body of the German plane. It fell straight into the ground. As Murphy pulled up, an FW-190 passed him, firing as he went. Murphy used the P-47’s superior diving speed to make a tight diving bank to the right 500 feet off the ground. As the FW-190 flew after him, it shuttered and stalled, falling to the ground.

Captain Cameron Hart shot down an FW-190 and then saw four on his tail. Hart clawed at the Germans, scoring hits on one and doing a barrel roll to evade the others. “Those Jerries were really aggressive and good, hot pilots,” he said later.

The Death of Heinrich Bartels

The Wolfpack of the 62nd Squadron had a good day, though, losing only Lieutenant Charles E. Carlson for 34 German kills. Among the German dead was a leading ace, Sergeant Heinrich Bartels, a Linz native and Knight’s Cross recipient. Bartels had just shot down his 99th kill when a P-47 caught him unaware. The P-47 shredded Bartels’s Me-109 named Marga, and the plane plunged to earth just outside Bonn. Neither the plane nor the pilot’s body were found until 1968, as the Me-109 slammed deeply into the ground near Gudenau Castle.

Other Luftwaffe pilots suffered equally tragic fates. Lieutenant Willi Bach’s FW-190 took a stream of bullets, and he made no attempt to escape before his plane hit the ground near Rottingen. Friends of Lieutenant Klaus Gehring watched in horror as he bailed out of his stricken FW-190. But his parachute snagged on the plane’s tail, and pilot and plane fell into the ground together.

The Trier Air Battle

Around Trier, the Luftwaffe tried its best to thwart American and British heavy bombers with ample bravery but little success. The RAF dispatched 153 Lancasters to hammer the railway yards through cloud cover. It was one of the toughest raids Trier suffered during the war, and the British lost a single Lancaster.

In the evening, 27 Lancasters and three Mosquitos of 8 Group flew to attack the Gremberg railway yards. The force was split into three formations, each led by an Oboe-equipped Lancaster with an Oboe Mosquito as a reserve leader. Oboe was the code name for the British radio signals that enabled pathfinding bombers to locate targets for marking. When the bombers reached the target, the clouds cleared, and the decision was made to bomb visually. That message did not reach the leading Lancaster, a 582 Squadron aircraft piloted by Squadron Leader Robert A. Palmer, a holder of the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Although his plane was damaged by flak, Palmer kept on course and dropped his marker bombs. But the plane went out of control, and only the tail gunner escaped by parachute. Squadron Leader Palmer, on his 110th mission of the war, was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross, the only Oboe VC of the war. “He was determined to complete the run and provide an accurate and easily seen aiming point for the other bombers,” read his VC citation. “He displayed conspicuous bravery. His record of prolonged and heroic endeavor is beyond praise.” His body is buried in the Rheinberg War Cemetery with the other men who died in the Lancaster.

The Trier air battle attracted planes of both sides. Jagdgeschwader 4 and Jagdgeschwader 11 tried to head off the incoming American bombers but instead ran into P-51 fighters of the 479th Fighter Group, which shot down a dozen FW-190s, three of them falling to Major Arthur E. Jeffrey alone. The Americans lost only a single Mustang.

Desperate German Ground Attack Sorties

Despite the overwhelming Allied air might, the Germans tried to take advantage of the weather break to fly their own attack missions. Jagdgeschwader 4 sortied 20 FW-190s to attack ground targets near Bastogne and ran into heavy American flak and fighters. Six FW-190s were shot down. Oberleutnant Markoff was able to nurse his battered fighter back to the Reich, where he bailed out, returning to his airbase by train. But Lieutenants Haug, Nefzger, Dehr, and Walter were listed as missing, while three others, Lieutenant Dietman Bischoff, Lieutenant Edward Schmidt, and Sergeant Hoflich, were taken prisoner.

Jagdgeschwader 11 took a pounding trying to stop the bombers, losing 12 pilots killed, four missing, and 11 wounded in wild battles all above the Moselle. Jagdgeschwader 3 lost four pilots killed or missing, along with another four who bailed out while attacking the 322nd Bombardment Group as it parceled out bombs on the Euskirchen rail bridges. Twenty JG 11 Me-109s piled into the Americans, but they lost six of their number. Lieutenant Adolf Tham rammed a B-26 with his Me-109 and was able to parachute away from the falling wreckage. The hail of return fire killed two pilots immediately, and another died later of wounds received.

“There Were No Parachutes”

Down below, ground troops on both sides watched this ferocious air battle. William Breuer, a mortarman with the 87th Mortar Battalion near Sadzot, Belgium, mistook the German fighters for jets and reported: “As the miles-long stream of bombers was nearly overhead, bright and twinkling specks high in the sky, the initial elation the mortar men felt on the ground was quickly replaced by a chilling surge of concern. From out of the bright sun, a swarm of [German] fighters pounced on the American bombers and the ultra-high-speed Luftwaffe planes promptly began knocking Flying Fortresses and Liberators out of the sky. Several bombers, burning brightly, plunged to the earth with their crews…. There were no parachutes. The P-47 Thunderbolt and P-51 Mustang fighters that were accompanying the four-engined craft sought in vain to protect the bombers from their tormentors, but the speedy [German] fighters simply flew faster….The sky was filled with pieces of destroyed American bombers which were tumbling and spinning downward in a crazy-quilt pattern—part of a wing here, a portion of a fuselage there, a tail assembly twisting and turning in grotesque movements … crisscrossing the winter skies were countless vapor trails….”

P-51s of the 479th Fighter Group slammed into another group of FW-190s and shot down 12 Germans for the loss of one Mustang. Major George Ceuleers had four kills, including one that he blasted from behind the tail of another P-51. Ceuleers pulled behind another German, and the Luftwaffe pilot did not even bother to fight. He leaped from his FW-190, and Ceuleers got a kill without firing a shot.

It was a tough day for the German pilots. Jagdgeschwader 77’s 3rd Group, under Captain Armin Kohler, had a typical day waiting out the low clouds in the morning with games of cards until noon, then an urgent scramble to stop a group of enemy medium bombers headed for the Reich. They took off at 1:45 pm and burst upward through the mist into a blue sky above. The Group’s 11th and 12th Squadrons ran into a horde of P-47s, which nearly wiped out the 12th Squadron before the 11th could intervene. Two pilots were killed and five wounded before they returned to their base near Dusseldorf. Lieutenant Sepp Unverzagt was able to bail out without injury.

The 12th Squadron, flying in to help its buddies, also suffered heavily. Lieutenant Walter Wildenaur jumped from his plane and was machine-gunned as he fell to earth, but he survived. Lieutenant Hasso Frohlich belly landed his battered Me-109 near Walsum. Other Me-109 pilots, forced to drop their fuel tanks, found themselves short of aviation gas after a few minutes of dogfighting and had to flee for the nearest airfield, using the Cologne Cathedral as a reference point. To make matters worse, many of the airfields around Cologne were damaged by the day’s American strafing and bombing. A complete Schwarm of four planes was destroyed landing at Koln-Ostheim, but the four pilots survived. Captain Kohler himself had to land at Ostheim. The planes landed at scattered airfields, and it took days to reorganize the battered group. It had lost 20 planes for the probable claim of two American P-47s.

Other Luftwaffe pilots were lost forever. The body of Major Eric Putzka of JG 11 was never found. Sergeant Holland was last seen being chased by 30 P-47s. The 10th and 11th Squadrons of JG 11 lost 16 pilots killed or missing.

The famous Ace of Spades, JG 53, went into action with a dozen Me-109s taking off from Germersheim to intercept P-47s reported to the west. They met up with a pack of P-47s at 10,000 feet. Lieutenant Wilhelm Westhoff, a veteran of North Africa, had to parachute into captivity. The equally renowned JG 26 was also in battle, flying defensive support of panzers advancing on the Meuse. Some 23 FW-190s launched at 11:14 am and immediately found Americans swarming all over their airfield at Furstenau.

Six of the German fighters were immediately in a dogfight, and the remainder were able to head for the battle zone, attacking a group of B-26 bombers. Two Marauders were shot down before the P-47 escorts showed up and shot down four German fighters at no cost to themselves. Five JG 26 planes crash-landed just east of the Ardennes.

The Luftwaffe’s Losses

Meanwhile, the Anglo-American air onslaught rolled on. The 394th Bomb Group, Colonel Thomas B. Hall’s Bridge Busters, sent 32 B-26 bombers over Prum in the afternoon to punch out the rail marshaling yards. Lieutenant Fred Riegner’s Marauder was hit by flak during its bomb run and ended in a flat spin. Two crew members, 2nd Lieutenant Lester Fowell and Sergeant Wilson Voorhis, Jr., escaped the spinning plane to become POWs.

That night, the RAF’s No. 2 Tactical Group Mosquitos got airborne. Mosquitos of the 138th and 140th Wings stalked the rear of the German 6th SS Panzer Army, looking for vehicles of all sorts. They fired off 80,000 machine-gun and cannon rounds at ground targets near Blankenheim, Mayen, Bitersborn, and Prum. German night fighters countered with raids by 88 aircraft sent on harassing patrols in the Metz-Sedan area.

Sergeant Albert Johanntges and his Junkers Ju-88 crew had an adventure. Their radio guidance and compass went out, and they got lost. Low on fuel, they spotted a railway station just west of Liege, decided that was a suitable target, and dropped their bombs on it. Just as they pulled out, a night fighter drilled their Ju-88, and pilot, observer, and wireless operator bailed out to captivity. The bombardier died with the plane.

The Americans had two night fighter squadrons in the Ninth Air Force, and they flew only 13 sorties, strafing Germans around St. Vith and bombing towns near Nohfelden, losing one Northrop P-61 Black Widow. The three active night reconnaissance groups were also busy reporting on the heavy bombing of Trier—the RAF had left it in flames—and on German troop movements.

Light Losses For the Eighth and Ninth

The 23rd was finally ending, and both sides now began to count the gains and losses. The Luftwaffe had put up its greatest effort of the campaign, reporting 800 sorties. But the missions were to little avail. Fewer than half of the German fighter sorties were in the battle area. The Luftwaffe had split its work between attacking Allied fighters and ground support. The big attack planned for Bastogne had to be called off due to overwhelming Allied presence. Some 63 valuable fighter pilots were killed or missing, with another 35 wounded. Their impact on the ground battle was minimal. The boss of JG 27, Colonel Gustav Rodel, was exasperated with his pilots, accusing 20 percent of them of breaking off attacks early and returning to base. Court-martial was threatened for pilots who avoided their duty in the future.

Another problem was the lack of air cover over the German advance. Orders for the 24th insisted, “Fighters must avoid air combat and penetrate without fail into the area above the foremost panzer spearheads.” That would not be easily achieved, given the Allied air superiority.

The Ninth Air Force summarized the German effort as follows: “It appears that the enemy during the morning was able to enter the battle area, whereas during the afternoon he was prevented from doing so either by the nature of his mission or by Allied aircraft. His effort for the day is best described as an aggressive defensive effort.”

In contrast, the American Ninth Air Force flew 696 sorties, shooting down 91 enemy aircraft for a loss of 19 of their own, with an additional loss of 35 medium bombers.

The Eighth Air Force claimed 75 enemy aircraft destroyed while losing one bomber and seven fighters. Ground claims by the fighterbombers totaled some 230 vehicles of all types. The first day of good flying weather had been a disaster for the Luftwaffe and the German ground troops. German Army Group B reported to Berlin, “In the entire army area, there was heavy enemy flying activity with fighter-bomber attacks on German spearheads as well as bomb drops from four-engined bombers on roads and traffic targets in the attack zone.”

To make matters worse, the Luftwaffe was running out of aviation gasoline, just as the ground forces were running out of fuel as well. The Luftwaffe’s high command ordered the air force to “immobilize all transport not needed for immediate combat support in order to conserve fuel.”

It was a hard day for the Luftwaffe, and a glorious day for the Allied air forces. But perhaps the happiest man on the 23rd was the ebullient George Patton. During the heavy rain and mud of the Lorraine campaign in November, Patton had asked his chaplain, Father James O’Neill, to prepare the now-famous prayer for good weather.

“All I Request is Four Days of Clear Weather”

On December 23, the prayer went out to the men of the U.S. Third Army: “Almighty and most merciful Father, we humbly beseech Thee, of Thy great goodness, to restrain these immoderate rains with which we have had to contend. Grant us fair weather for Battle. Graciously harken to us as soldiers who call upon Thee that, armed with Thy power, we may advance from victory to victory, and crush the oppression and wickedness of our enemies, and establish Thy justice among men and nations. Amen.”

Supposedly, when the weather cleared Patton ordered that O’Neill be decorated for composing an effective prayer. However, the prayer was not, as the movie Patton suggests, composed during the Battle of the Bulge. But Patton did write a prayer himself on the 23rd, asking for clear skies, which concluded:

“Sir, I have never been an unreasonable man, I am not going to ask you for the impossible … all I request is four days of clear weather … so that my fighter-bombers can bomb and strafe, so that my reconnaissance may pick out targets for my magnificent artillery. Give me four days of sunshine to dry this blasted mud…. I need these four days to send von Rundstedt and his godless army to their Valhalla. I am sick of this unnecessary butchery of American youth, and in exchange for four days of fighting weather, I will deliver You enough Krauts to keep Your bookkeepers months behind in their work. Amen.”

Patton got his wish. The weather would remain clear for the next four days, and the Allied air forces would dominate the skies over the Ardennes. But severe fighting on the ground and in the air lay ahead. The Allies had won a massive victory in the air with “the war’s most beautiful sunrise.”

As the guy who wrote this piece, I can definitely say this…the fella who did so should be beaten up!

LOLOLOLOLOL

What this article, and so many like it, is really saying is that the American Army could not beat the German Wehrmacht in a fair, one on one fight without the assistance of their air force. It’s a damning indictment of the ability of the American military at that time and undermines the myth of Patton’s genius as a commander. The Americans were stopped from advancing by the weather; the Germans were not.

I disagree. The American citizen soldier could and did hold their own against the German Army. The 10th mountain division defeated their German counterparts in the Voges Mtns. without any air support. The 509 help the seven roads at Bastogne. The Germans were well trained and battle hardened but they were not invincible.

I disagree with your premise. An army is a system of systems and the US had superior production, logistics, air power, naval power and artillery. Once the allied forces were on the shores of France, it was just a question of time and casualties.

The weather did not stop the allies from advancing, it was lack of supplies that forced their offensive to stop. Until they halted, the Germans were being pressed so hard they could not set up a defense in France. What the weather did was prevent the allies and the Germans from using their air forces. Since the allied air force had supremacy, bad weather was advantageous to the Germans.

And then there were the Germans. Due to the terrain, the Ardennes was viewed as a quiet sector. The green 99th and 106th divisions were sent there, the 28th division was resting there and divisions covered a greater frontage than they normally would. In the meantime, they were attacked by two panzer armies. It was not a fair fight because the Germans created local superiority, where 406,000 Germans faced 229,000 Americans. They counted on the weather to deny the use of the air forces as force multipliers so they could maintain that advantage. Their plan also risked the narrow roads of the Ardennes that limited their ability to maneuver in the forests and ultimately played a key role in the failure of the offensive.

There are plenty of incidents in which the US won evenly matched fights. And by any measure, Patton’s actions during the battle were comendable. He anticipated the need to rotate his army from attacking to the east to attacking to the north and realigned them while in contact with the enemy in a very short time. That is an incredibly difficult task that his command accomplished before his counter-attack was even launched. His attacks from the south combined with the UK/US attacks from the north stopped the German offensive and eventually forced their retreat.

The German offensive was never going to reach Antwerp even if it remained overcast for a month. They had supply problems before the allied counter-attacks and once the allies reacted, the Germans no longer had local superiority. Again, it was just a question of how long it would take and what the casualties would be. What this article shows is how powerful a force multiplier the allied air forces were, which reduced the time it took to defeat the Germans and reduced allied casualites.

Mark, as the author of this piece, I respect your criticism, and would like to discuss it further with you.

I will say this, so others can see it:

This article was assigned to me for a specific purpose and a specific intent, which I carried out. Obviously, it is not a comprehensive history of the Battle of the Bulge, which has required books the size of John S.D. Eisenhower’s “The Bitter Woods” and Peter Caddick-Adams’ “Snow and Steel” to properly describe and analyze, among others.

Many factors enabled the Germans to launch the Ardennes Offensive. Many factors doomed it from the start, and many factors defeated it in battle, ranging from the sheer idiocy of Hitler’s plan to the American use of the proximity fuse.

British military historian Sir Max Hastings notes just that in his book “The Secret War:”

He quotes Winston Churchill as saying, “All things always on the move simultaneously.” The more I study and write about World War II, the more I believe it to be so.

You can find me at [email protected]

Very respectfully,

David H. Lippman

Beat the German in a fair one on one fight ? What do think this was, a game of cricket ?

The Germans made their lightning advances by using superior air power at the time in conjunction with ground forces. Was this unfair ?

The allies did NOT stop for the weather, their fuel and other supplies were stretched. The ‘’Red Ball Express ‘’ was struggling to keep up.

If they had succeeded in a break through at Bastogne the northern allied armies would have destroyed their ill supplied columns .

Who painted the painting at the beginning of this article? Could I purchase a print. Thanks Alex

I have a Question. Were the Canadian Air force involved at all. My dad was ground crew for the Typhoons.

This article has been a really helpful insight into the role of the weather in the Battle of the Bulge. However, I couldn’t help but noticed, you have quoted numerous primary sources without a reference, and I was wondering where you sourced this information. I’m currently researching the Battle of the Bulge and if you can remember where you accessed any of the primary sources quoted here it would be of great use. Again, great article!

Hi Mark. Loved this article. Just bought Beevors book about it as finally arrived at my Katikati bookstore.

Have you read it? Cheers from Roy {Fellow Kiwi, ex-MilitaryPolice and History Teacher]