By Christopher Miskimon

In the early morning hours of March 23, 1943, the U.S. 1st Infantry Division was preparing to attack. The unit was arrayed east of the Tunisian town of El Guettar, roughly 50 miles south of the now famous Kasserine Pass, where the U.S. Army had suffered a sharp defeat just a month earlier.

Kasserine had been a heavy blow to the novice American Army, determined but still learning its deadly trade through costly lessons. Now, that Army had its feet under it again and was on the move. Advances over the previous week had left it in possession of El Guettar and now the division was poised to advance farther. To the southeast, the British Eighth Army, under the command of Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, had chased the Axis forces all the way from Egypt and now was being held up at the Mareth Line, a stoutly defended fortified position.

To relieve pressure on the Eighth Army, the U.S. 2nd Corps, of which the 1st Infantry Division was a part, was ordered to attack down Highway 15, a road leading east from El Guettar toward the enemy-held town of Gabes. At worst, this would draw some Axis troops away from Mareth and make it easier for the British. At best, if the Americans could break through to the sea it would cut off large numbers of German and Italian soldiers from their comrades to the north in Tunis. So it was that the “Big Red One,” as the 1st Infantry Division was known, was poised to attack on the morning of the 23rd.

Attached to the division was the 601st Tank Destroyer Battalion, there to bolster the infantry’s ability to engage the German tanks that had been so skillfully used against the Allied forces. On this day it would find itself fighting for its life against the battle-hardened 10th Panzer Division as it launched a preemptive spoiling attack against the Americans. (A spoiling attack occurs when the enemy, anticipating an offensive move, attacks first, thus “spoiling” the impending assault.)

The 601st would prove instrumental in beating off this move, showing that the U.S. Army was in fact learning its lessons, honing itself into the weapon it needed to be to inflict final defeat on Nazi Germany.

The GMCs of the 601st

The 601st was a standard tank destroyer battalion for its day. Commanded by Lt. Col. H.D. Baker, the unit was equipped mainly with the M3 Gun Motor Carriage (GMC), a standard M3 half-track hastily converted into a tank destroyer with the addition of a 75mm M1897 cannon, the “French 75” of World War I fame. The vehicle had been intended only as a stopgap weapon to train American troops until a purpose-built design could be produced.

When Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa in November 1942, found the Army still short of weapons, several tank destroyer battalions, including the 601st, nevertheless went into action with it. The M3 was a reliable vehicle, and its cannon packed a good punch, able to penetrate three inches of armor at 1,000 yards, respectable at that point in the war. On the down side, the vehicle had thin armor and the gun was not fully enclosed. The crew was protected only by a thin gun shield, leaving it vulnerable to artillery and flanking fire.

The battalion had a few M6 GMCs as well. This was a Fargo ¾-ton truck mounting a 37mm light antitank gun on the bed. The 37mm weapon was obsolete by this stage of the war, and the crew was likewise dangerously exposed. Most commanders had learned to keep them in the rear out of harm’s way. On March 23, the 601st had 31 M3s (out of 36 assigned) and five M6s serviceable. The rest had been lost during previous actions. The tank destroyers were thus divided into three companies, A, B, and C. The battalion also had logistical and reconnaissance elements to round out its strength.

The Road to El Guettar

In the preceding few days, the 1st Division had taken Gafsa and El Guettar before seizing the hills immediately east of the latter town. Also attached to the division was the 1st Ranger Battalion under the command of Colonel William O. Darby. The Rangers, along with the Big Red One’s 18th Infantry Regiment, had cleared Axis troops from the area. That done, the division commander, General Terry Allen, readied his command for its next advance toward Gabes.

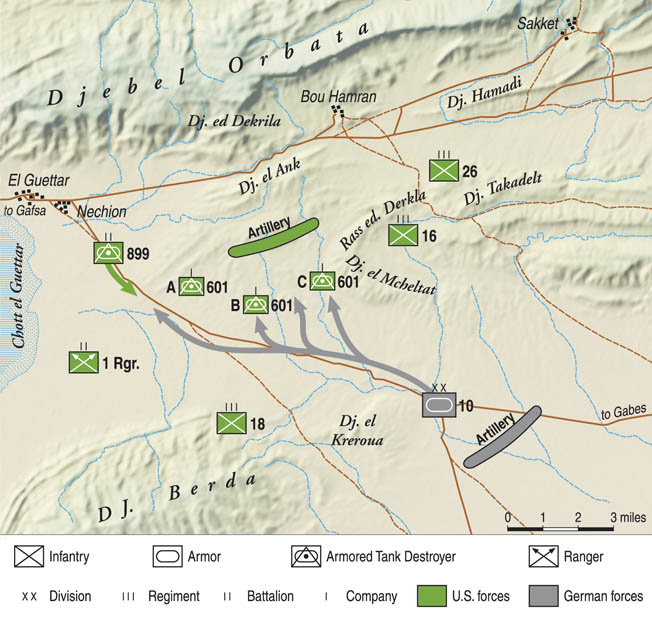

The 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 18th were sited south of Highway 15 on the Djebel Berda. The rest of the division’s infantry battalions were deployed along the Keddab Ridge, which rose from the ground just north of the road. The 3rd Battalion of the 18th, 3rd of the 16th Infantry, and the 26th Infantry Regiment were set up from south to north, respectively. The rest of the 16th was either in reserve in El Guettar or back in Gafsa. The road essentially went between Djebel Berda and Keddab Ridge before curving northwest to El Guettar. South of the town was the Chott El Guettar salt lake. Its eastern side bordered an expanse of marshy ground impassable to vehicles. Just north of the road was Hill 336, also called Wop Hill. The 18th Regiment’s command post was there.

The 601st was positioned just north of the road overlooking it, assigned to protect two artillery battalions moved forward to support the advance. Baker deployed his B and C Companies in front of the artillery positions and placed Company A overlooking the road from the hillside to the north. A line of outposts in front of B and C Companies were occupied by two reconnaissance platoons backed up by two M3s and several of the M6s. The various units seemed ready to continue their attack.

A Fighting Retreat

Unfortunately, the Germans were also prepared to attack, and they landed their punch first. They had perceived the damage an advance down Highway 15 could cause and sent the 10th Panzer Division forward. The 10th Panzer was one of the strongest units the Axis had left, though it was hardly at full strength with only 57 tanks and about the same number of lighter armored vehicles, such as half-tracks and armored cars. The tanks were supported by both infantry and artillery, and some air support was also available to the Germans.

The first sign of the impending assault came at 0445, when a German motorcyclist rode into the line of reconnaissance platoon outposts and was captured. When questioned, he stated the 10th Panzer Division was going to attack at 0500. Word was quickly passed up to the division headquarters, and the tank destroyer men prepared to receive this attack in the scant few minutes they had left.

Baker was concerned about his deployments. He had set out his companies to protect the artillery primarily against infantry deployments, not a concerted attack by armor. Still, he kept his soldiers where they were. The enemy could not come down the road without exposing itself to the fire of A and B Companies, and the marshy ground near the salt lake would keep any armored vehicles from moving out of range. If the Germans moved off the road to the north, then C Company could engage as well. There really was no time to make any movements anyway.

Within a few minutes, the men in the outpost line began to hear the sounds of armored vehicles approaching from the southeast. Their eyes strained in the moonlight to see any other sign of the enemy. Finally, they spotted 16 German tanks bearing down with several hundred infantry in support. The Americans held their fire as the mass of armor and men bore closer, then opened point-blank fire at a mere 200 yards. The reconnaissance platoons had been liberally issued with machine guns, and they now used them, pouring fire into the enemy infantry. Several of the truck-mounted 37mm guns on the M6s joined in, firing canister rounds at the foot soldiers and armor-piercing rounds at the tanks.

While the German infantry took heavy casualties, the tanks kept moving forward, impervious to the rounds fired at them. They replied with their own guns, the experienced Afrika Korps soldiers seeking out American vehicles with tracer fire from their machine guns. It was a proven tactic. They would fire the coaxial machine guns aboard their tanks in a wide arc. When the bullets struck the metal of an armored vehicle, the tracer rounds mixed in would ricochet up into the air, revealing its presence. The Germans would then open fire with their main gun. Two half-tracks were hit in short order. As the pressure became too great, both American platoons fell back, stopping twice to fight delaying actions before retreating to the Company A position on the hillside.

Over One Hundred German Tanks?

Dawn was beginning to creep over the eastern horizon. The German force split, with some branching off to attack the B and C Company locations while the main force continued along the highway toward El Guettar. Thirty German tanks were counted in the main group, while the Americans estimated a total force of over 100 tanks. This was, of course, more than the 10th Panzer Division had available. In the Americans’ defense, during the swirling chaos of combat it is really quite easy to overestimate the size of an enemy force. With the dust and smoke of firing and the mental stresses involved, an armored car, half-track, or even a truck can be easily mistaken for a tank.

That force must have appeared large indeed to the men of B and C Companies as it advanced toward them, the sun at its back. Each company had placed two platoons forward in line with the third platoon in reserve. The tank destroyers were hidden behind the low, rolling hills of the area. Forward observers relayed to them the approaching direction and distance of the Germans. When a crew was ready to shoot, the half-track was driven to a firing position at the top of their hill or ridge. As quickly as possible, it would fire at the enemy tank before backing down the slope out of view to await another target.

It became a deadly game of cat and mouse as the German tankers tried to seek out the continually moving American destroyers. As the Germans hunted, the accompanying infantry moved through the hills attempting to infiltrate the U.S. position. When they appeared, the Americans would fire at them with machine guns, Thompson submachine guns, and the occasional crash of a high-explosive shell from the 75mm cannon. All the while, enemy artillery crashed into the hillsides, raising huge clouds of dust and smoke. More dust was raised by the half-tracks themselves as they alternated firing positions to keep from being zeroed in on by the Germans.

Lt. Yowell’s Account of the Chaotic Battle

The scene quickly devolved into the hell of combat, the booming of cannon, the chatter of machine guns and Thompsons, the screams of the wounded and dying, everything obscured by dust and haze. The action soon became so intense that to keep up their fire on the closing German tanks, the tank destroyer crews were increasingly forced to stay in one firing position too long. This allowed the enemy easier shots, and one after another, tank destroyers were hit, many of them burning.

One of Lt. Col. Baker’s platoon leaders, a Lieutenant Yowell, was in command of B Company’s Third Platoon during this action. His report highlighted the confusion and closeness of the fighting. As the Germans approached at dawn, they closed to within 1,000 yards but were largely hidden by the terrain. Yowell repositioned several of his M3s to new firing points to better engage them.

He wrote, “Sergeant Raymond maneuvered his gun and destroyed a Pz VI [Tiger I] with six rounds, four of which bounced off the heavy armor. Sergeant Raymond fired one more round, at the same range, at a following tank, Pz IV, and it caught fire immediately. His halftrack was destroyed before he could fire another round.”

Raymond’s tank destroyer was hit three times and caught fire; he had made the mistake of firing seven times from the same location, though with the intensity of the fighting he likely had little choice. The crew bailed out and reported to Yowell, who sent them to the rear on foot. The other three M3s of his platoon kept up their fire on the Germans.

“I saw Corporal Hamel destroy a Pz IV, and Sergeant Nesmith knocked the turret off a Pz IV at about one thousand yards range,” Yowell reported. “Enemy infantry came in very close and their tanks were laying smoke while they brought up line after line of tanks. I estimated from four to five lines, with fifteen to twenty tanks in each line. There were tanks in groups of sixes and a column of tanks along the southeastern ridge, also. There were over one hundred tanks. I am sure of this.”

Yowell’s account illustrates the chaos of the engagement; his identification of the Pz VI Tiger tank indicates that a company of the German 501st Heavy Tank Battalion, attached to the 10th Panzer, was present at El Guettar that day. The other platoons of B and C Companies fought in much the same manner over the course of the morning, exchanging fire with platoon-sized elements of German tanks and fending off their infantry with a combination of machine-gun and cannon fire.

Breaking the German Momentum

The American artillery just behind the two tank destroyer units was engaged mainly in supporting the infantry in the surrounding hills, but the guns were able to occasionally fire into the Germans advancing in front of them. The shellfire was ineffective against the tanks but it did force the armored vehicles and infantry to spread out.

As this action was taking place, the main Axis force of 30 tanks was moving toward El Guettar, clustered around Highway 15, moving past B and C Companies and into the range of A Company. The German tank crews spotted the Americans on the hillside and called on their artillery, which fired a thick barrage of smoke rounds onto A Company. When the cloud dissipated, the German armor was still 2,200 yards away, extreme range for the M3s. The enemy column was getting too close to El Guettar and the supplies the division had stockpiled there. Baker ordered the company to open fire despite the distance, hoping to repel the Germans before they could threaten the town.

Things now began to go badly for the Germans. Though they managed to hit one tank destroyer, the incoming fire was too heavy for them and they began to skirt farther to the south in an attempt to get out of range of the Americans on the hill. When they did so, they ran into two obstacles: the marshy ground south of the road and a minefield laid earlier in a dry lake bed. Their momentum ruined, the Germans started to withdraw, pausing to hook tow cables to half of the eight burning or wrecked tanks that now littered the ground below Company A.

Baker noticed with respect the superior German ability to recover their losses on the battlefield and under fire, something his unit was as yet unable to do. The remaining tanks, dragging their disabled fellows behind them, limped away to the east. The threat to El Guettar was, for the moment, over.

The fleeing Germans were not completely done, however. Those tanks that were still battleworthy turned north and joined their brethren who were still attacking B and C Companies. Yowell watched them.

“They fanned out and started toward us. All this time, Staff Sergeant Shima was keeping a steady stream of .50 caliber machine gun bullets on the infantry. He also pointed out tank targets with his tracers….”

Sergeant Nesmith’s half-track was hit but could still move. One of his men was killed, and the rest of the crew was wounded. Within moments it was hit again, knocking it out of action for good. Another M3 was hit shortly afterward but without casualties. Yowell ordered the crew to transfer its ammunition to one of the still operational tank destroyers. As the two crews busily passed 75mm rounds, the receiving M3 was hit as well. Yowell was down to two working half-tracks and very little ammunition. He pulled them back to the next ridge and continued the desperate fight.

“Death Valley”

Above the valley floor, soon to be christened “Death Valley” by the Americans, Captain Sam Carter of the 1st Battalion, 18th Infantry Regiment had watched the entire battle unfold from before dawn. “There were red, white and blue tracers being fired…. Soon these colors were joined by green, purple, yellow and orange tracers. Soon after this the larger guns began firing. It appeared that every time there were point ricochets these would be followed by the large caliber guns. It was very dark at this time and nothing could be seen except the source of this large volume of fire slowly moving westward … daylight started breaking and before us in the valley was an entire panzer division.”

As Carter watched, the tanks moved toward the American lines in a giant armored square, mixed in with other armored vehicles and infantry. Once the sun rose over the eastern horizon, the artillery fire started and he had a ringside seat to the 601st’s fight for its life.

“Soon the valley was just a mass of guns shooting, shells bursting, armored vehicles burning and tanks moving steadily westward,” Carter would later write. “We sat in awe watching the attack….” At the same time, he and his men were worried; if the German attack succeeded, the battalion would be cut off. Fortunately, Carter also got to see the German tanks run into the minefield and take the flanking fire of the tank destroyers.

Finally, at about noon the remaining German tanks gave up the fight and withdrew, a few of them taking up hasty defensive position to the east, out of range of the tank destroyers. Carter also saw the German tank crews dismount to recover their disabled vehicles. “This was done in the midst of artillery fire which did not seem to faze those working outside the tanks at all,” he commented.

After a while, a number of M10 tank destroyers, improved models with a 3-inch gun mounted in a turret, came moving down the road from El Guettar. The German tanks that had taken up defensive positions quickly moved to hull-down firing points, only their turrets showing. Several of the M10s were quickly knocked out, and the rest fled to cover. At about the same time, Carter saw a group of German prisoners being led in. Many of them were crying. When the American officer asked them why they were weeping, they told him this battle had been the first time they had ever been stopped by mere artillery and infantry.

Down below, the field now became quiet as the fighting seemed to pause. The 601st had taken heavy losses in both men and vehicles. Both the artillery battalions they were screening had been forced to spike their guns and retreat. Shortly after noon, some of the tank destroyer men saw an American half-track towing a small gun approach. Thinking it a separated group of U.S. troops, they held their fire. When it was still 400 yards from the 601st line, the half-track stopped and seven Germans jumped out. As they started to set up their cannon, a tank destroyer crew scrambled to its own gun. The Americans fired three rounds, setting the captured half-track ablaze and killing five of the enemy soldiers. The remaining two fled but were found hiding in a ditch and taken prisoner.

Panzergrenadiers Driven Back

Little else happened until 1500, when a swarm of German planes appeared overhead and began strafing and bombing the American positions. The 601st replied with its few .50-caliber machine guns. Shortly afterward, a message came down from the division headquarters. A German message had been intercepted ordering another attack for 1600 hours. Shortly afterward, another message informed of a delay to 1640 so that German artillery could get into position. The now depleted battalion prepared to meet the enemy for a second time that day.

When the appointed time came, men of the 601st saw what looked like two battalions of infantry advance with tanks behind them. In actuality, it was two battalions of panzergrenadiers along with a motorcycle battalion and the remains of two tank battalions behind them. The artillery battalion that had caused the delay had arrived and was in support. The enemy infantry moved forward smartly, but the tanks held back. Baker guessed they were waiting for the infantry to clear the way. They would never get the chance; the Americans were ready for them.

The German foot soldiers had closed to 1,500 yards when the U.S. artillery opened fire, raining down a hell of exploding steel. Both 105mm and 155mm guns went into action, their shells armed with time fuses set to detonate above the ground. This spread the shrapnel in a wider, deadlier arc. The incoming rounds burst in puffs of black smoke directly over the heads of the attacking Germans. Scores of them fell.

The 601st joined in with its remaining weapons. Machine-gun fire raked the enemy, 75mm high explosive shells dropped on them, adding to what the field artillery was already doing. Baker watched as one of his sergeants “bracketed rapidly and fired as fast as he could, making 5-mil deflection changes. He dropped high-explosive shells at 7-yard intervals across the German lines.”

Soon, the Nazi troops could take no more; they ran for the cover of a ridgeline behind them. That placed them safely out of the tank destroyers’ fire, but the American artillery was not done yet. It continued to fire onto the reverse slope of the ridge and finished the job. The few survivors stole off to rejoin the tanks and retreat. For the 601st, the day’s fighting was over.

37 Panzers Knocked Out, 200 German Infantry Casualties

As darkness spread over the battlefield, the 601st took stock of its situation. Fourteen men had been killed. Of the 31 M3s that had started the battle, 21 had been knocked out. Only eight of them were repairable. One of the tiny M6s had been lost also, as well as nine trucks and four regular half-tracks. Several of the trucks had been hit while scrambling across the battlefield to deliver ammunition. Besides those losses, the unit’s ammunition expenditure showed how intense the fighting had been. The battalion’s normal load of 75mm ammunition was 2,844 rounds. It had expended 2,740, as well as nearly 50,000 rounds of small-arms ammo.

To show for it all, 37 German tanks had been knocked out or disabled, with the 601st getting credit for 30 of these. The rest were attributed to mines and artillery fire. The tank destroyer unit was also credited with 200 of the German infantry casualties. On a battlefield as chaotic as that of El Guettar, the exact cause of casualties or destroyed vehicles is open to speculation, but there is no doubt the 601st did its share of the work that day. General Allen gave the battalion credit for protecting the 1st Division’s vulnerable supply lines.

The German spoiling attack at El Guettar was a difficult fight for the Americans. Not everything had gone well, and losses had been sustained. They had taken the Afrika Korp’s best shot, however, and they had not given way. It was an impressive display after the previous defeats at Kasserine and elsewhere. While preparing for an offensive move, the 1st Infantry Division and the attached 601st had itself been attacked and forced on the defensive by a heavily armored enemy force.

German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel had once expressed a fear that the American, while new to war, would learn quickly. This fear was borne out in the hills east of El Guettar. The U.S. Army was learning its lessons. Soon it would be ready to teach a few of its own.

My father Michael W Stima was a tank commander 601st TD B Co and was awarded the Silver Star at that battle

The US Army was not supplied with top notched equipment at beginning of war The M3 was an inadequate tank destroyer at the time with pre WW1 French Artillery. The unit was very successful in rest of war . The Greatest Generation

Great uncle PFC Earl Lane 601st TD HQ Co received silver star for delivering ammunition to either B or C company on the 23rd. He was killed but remains never found listed on tablets of the missing memorial.