By Eric Niderost

On the morning of September 14, 1854, an Anglo-French fleet arrived off the coast of the Crimean Peninsula in the Black Sea. There were hundreds of vessels, including towering, three-decked warships, sleek frigates, and lumbering transports ready to disgorge their cargoes of men, horses, and equipment. The objective of the campaign was to take the Russian naval base at Sevastopol, some 25 miles to the south. Once Russian naval power had been neutralized, Czar Nicholas I’s ambition to nibble away at the crumbling Ottoman Empire and establish a Russian presence in the Mediterranean would be checkmated. Defeated and humiliated, the czar would have to sue for peace.

The Anglo-French expeditionary force landed at Calamita Bay—soldiers inevitably nicknamed it “Calamity Bay”—and it took five days to fully disembark. The French Army was much better prepared than the British, but the stoical redcoats did not complain. The first evening ashore there was torrential rain, a deluge that lasted all night. The British had to make do with their sodden greatcoats and a few dripping blankets. By contrast, the French had tents set up for even the lowest soldier, and the Turks had unique little “pavilions” that looked like something out of the Arabian Nights.

It was the first of a series of misfortunes that dogged the British Army throughout the Crimean campaign. The sad truth was that the British were woefully unprepared to wage a major campaign so far from home. They had no transport or baggage train of any kind, and the Quartermaster General’s Department had to create transportation on the spot—a daunting task under the best of circumstances. Foraging parties fanned out and bought carts and draft animals from the Tatars, local natives who had little love for the Russian czar. After much hard work, some 350 carts were assembled, but the British needed a minimum of 700 such wagons. That meant that the individual British soldier had no more rations or equipment than what he could carry on his back. An officer of the 42nd Highlanders listed a surprising number of items he carried, including “three days rations of salt pork and biscuit [9 pounds], cocoa and sugar in his haversack; shirt, hose, boots, brushes, shell jacket and sponges in his knapsack, greatcoat, claymore [sword], dirk and revolver.”

The men in the ranks carried even more supplies with them, including 50 rounds of ammunition for their Enfield rifle-muskets. These were relatively new weapons, with grooved barrels that put a spin on the new minié ball that gave it more power and accuracy. The British also favored two-rank formations, the legendary thin red line. London Times correspondent William Russell claimed to have coined the phrase (he originally called it a “thin red streak”). By contrast, the Russians, Turks, and French still used bulky column formations, large conglomerates of literal cannon fodder that relied on sheer mass, not firepower, to overawe enemies. The thin red line and superior firepower were the lone bright spots in an otherwise gloomy picture of hidebound allied tradition and incompetence.

Czar Nicholas was a political reactionary who used the Russian Army as an instrument of repression both at home and abroad. Turkey, called the “sick man of Europe,” was plagued by weak and incompetent sultans and a corrupt, antiquated government. The scent of decay was in the air, making the Russian bear rapacious and eager to tear into Turkey’s weakened body politic. The Crimean War began in late 1853, after a dispute between Catholic monks and Orthodox priests over the guardianship of Christianity’s sacred sites in Jerusalem. Both sides appealed to Sultan Abdul Mecid I. France had long been the protector of Roman Catholics in the Middle East, and Napoleon III saw the dispute as a chance to flex his political muscle. The Turkish government bowed to the emperor’s demands and gave protection rights to the French.

The czar was offended and sent an embassy to Constantinople to bully the Turks into changing their minds. The Russians also demanded a Russo-Turkish defensive alliance and the right for Nicholas to be the protector of all Orthodox Christians in the Ottoman Empire. This would make Turkey, in effect, a Russian client state, a puppet with the czar pulling the strings. The British government took a sudden interest in the developing crisis. It was a cornerstone of British foreign policy not to let any great power control Constantinople and the straits that connected the Black Sea with the Mediterranean. If Russian warships were allowed to enter the Mediterranean, it would no longer be a British “lake,” and the overseas route to India and British possessions in the Far East would be threatened.

Backed by British support, Turkey rejected Russia’s bullying demands, prompting the czar to invade the Turkish provinces of Moldavia and Wallachia. In response, British and French warships hurried to the straits to checkmate any Russian moves there. Turkey declared war on Russia in October 1853, but for the moment Great Britain and France stayed out the fray. The czar and his ministers realized that they were diplomatically isolated. Prussia was indifferent, Austria was hostile, and Great Britain and France were firmly if unofficially on the side of Turkey. A flurry of diplomacy went nowhere. Nicholas refused to compromise, in part because he feared that Russia would lose face. In November 1853, the Russians destroyed the Turkish fleet at Sinope.

Now Nicholas had gone too far. When he refused to withdraw from Moldavia and Wallachia, France and Great Britain declared war on Russia in March 1854. Allied troops were sent to Turkey, and eventually ended up in Varna, in modern-day Bulgaria, to block any Russian moves on Constantinople. At the time, the Russians had nearby Silistria under siege. If that town fell, the Russians might pour south. The Russians eventually lifted the siege, and the 120,000-man army began to evacuate the Danube provinces. The allies had done no fighting, but Varna’s dirty streets and polluted water spread disease. Cholera was soon raging through the ranks. The French Army was weakened, and many British regiments were decimated. It was decided that the allied effort should focus on Sevastopol, Russia’s major naval base on the Black Sea. The czar’s power had to be broken in one way or another—and the capture of Sevastopol would lessen his prestige and humble him enough to come to the peace table.

Now the Anglo-French expeditionary force found itself on the Crimean Peninsula in September 1854, some 25 miles from its objective. Cholera was still present, and throughout the voyage from Varna soldiers had continued to die of the disease. It was fortunate for the allies that the Russians did not contest the landings because at first it was organized chaos. A solitary Russian officer on horseback observed the landings, made notes, and then galloped away.

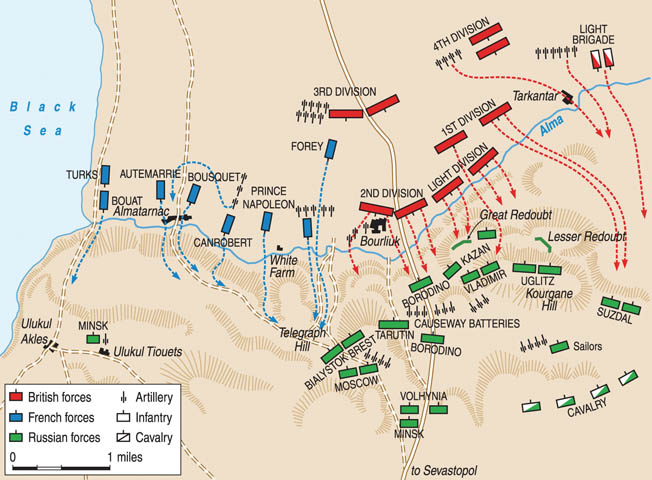

After a soggy night, the allied army marched out on the morning of September 19.The French were nearer to the shore, which gave them the advantage of having their right flank protected by allied warships. Eight battalions of Turks (about 7,000 men) under Suleiman Pasha marched with the French. The French 2nd Division, commanded by General Pierre Bousquet, marched next to the Turks, with the men of the French 1st Division under General François Canrobert forming the Gallic center. The French left was assigned to Prince Jerome Napoleon’s 3rd Division, while the 4th Division under General Elie Forey brought up the rear.

The French Army had little of the discipline that was so common in British regiments. They were heroes on the battlefield, filled with courage and élan, but plundering thieves on most other occasions. A frustrated Prince Jerome Napoleon, cousin of Napoleon III, futilely attempted to stop his men from sacking local villages. They ignored his angry remonstrations. The common French soldiers were rogues, their mood lightened by the beguiling presence of the cantinieres, female camp followers dressed in tight-fitting uniforms that mirrored their male counterparts, who sold brandy and extra rations to the troops. The French Zouaves—dressed in baggy red trousers, vests, and tasseled fezzes of Algerian origin—were favorites of their British comrades in arms.

General Sir George de Lacy Evans’s 2nd Division occupied the British front line of march on the right, with General Sir George Brown’s Light Division beside it on the left. The Duke of Cambridge’s 1st Division and General Sir Richard England’s 3rd Division followed in support, and elements of the 4th Division brought up the rear. Cavalry screening was provided by the 11th Hussars, 13th Light Dragoons, 8th Hussars, and 17th Lancers—men who would later achieve immortality when they participated in the Charge of the Light Brigade.

The ground was treeless and undulating, perfect for the movement of men, horses, wagons, and artillery. The allied forces covered an area five miles wide and four miles deep. After the rainy, miserable night, spirits soared with the rising sun, and a gentle sea breeze made the air fresh and clean. Long columns of redcoats marched as if in review, and regimental bands played stirring airs. The Highland regiments were particularly striking, large muscular men with swaying kilts, bobbing feathered bonnets, and skirling bagpipes. Russell of the Times noted: “The effect of these grand masses of soldiers descending the ridges of the hills, rank after rank, with the sun playing over forests of glittering steel bayonets, can never be forgotten.” This romantic vision of war was all too fleeting.

Soon the sea breeze diminished, replaced by sweltering temperatures. As the mercury rose, the sweat-drenched men were tortured by raging thirst. Parched and exausted soldiers began to fall out by the score. They were joined by cholera victims, soldiers whose burning fever and dysentery made them unable to travel another step. The trudging columns pressed on, leaving a detritus of sick and half-dead men in their wake. Lord George Paget, commanding the 4th Light Dragoons, did his best to get the victims up and moving again, with limited success. So many bodies lay sprawled on the ground that it looked as though a major battle had been fought.

First Clash at the Bulganak River

At last the Bulganak River was spotted ahead. Discipline momentarily evaporated as men broke ranks and ran to quench their thirst. The kilted warriors of the Highland Brigade did the same, but were quickly checked by their commander, Colonel Sir Colin Campbell, and ordered back into formation. Campbell, one of the most respected officers in the British Army, knew what he was doing. The colonel sent forward a detachment that filled water barrels to the brim, which were then distributed to the thirsty troops. The regiments who had rushed down to the river in a great stampede got the worst of it, because thousands of feet had churned up the sluggish stream and literally muddied the waters. Thanks to Campbell’s foresight, the Highlanders could fill their bottles with clean water.

A large Russian force showed up near the river, perhaps 6,000 infantry, a brigade of cavalry, and some horse-drawn artillery. Brig. Gen. James Brudendell, the seventh Earl of Cardigan, was sent out to reconnoiter with the 13th Light Dragoons and 11th Hussars, while the 2nd and Light (Infantry) Divisions were called up and placed in readiness. The Russian infantry left the field, but the czarist 12th Saxe-Weimar Hussars and Don Cossacks stood their ground. A hot skirmish developed, with troopers from both sides firing on each other from horseback. After 20 minutes of blazing away, not one man or horse had been hit. But the artillery was more deadly; Russian cannonballs were “bounding like cricket balls” according to one observer. One Russian round-shot managed to take the leg off of a British soldier. British artillery, 6- and 9-pounders, were brought up and flamed in counterbattery. The Russians seemed to tire of the artillery duel; they limbered up and withdrew south. The British had suffered four men wounded (two amputations) and five horses killed.

This was just an appetizer of war—the main course was yet to come. Seven miles away lay the Alma River and beyond the river a series of hills called the Heights of Alma. The Russians were not about to let themselves be bottled up in Sevastopol without a fight—if they were going to make a stand, the Heights would be the place to do it. Prince Alexander Menshikov, the Russian commander in chief in the Crimea, was sure that the Alma Heights would stop the Allies dead in their tracks. He assured Czar Nicholas that he could hold the Alma Heights for three weeks. Menshikov’s overconfidence was founded on a complete misreading of the British soldiers’ fighting abilities. The prince considered the British Army in the Crimea mere “sailors conscripted into military uniform.” He was not alone in his contempt of the British, although most Russians admitted that the French could fight. The memories of the first Napoleon were too fresh to think otherwise.

The Alma Heights began at the sea with a bluff called the West Cliff. Overlooking the sandy mouth of the Alma as it emptied into the Black Sea, the West Cliff rose precipitously about 400 feet. Two miles upriver was Telegraph Hill, so called because of a tower that originally was intended to be a telegraph station. Telegraph Hill and West Cliff joined to form a plateau. The main road to Sevastopol ran between Telegraph Hill and another elevation to the east named Kourgane Hill, some 450 feet high. Kourgane Hill was in many respects the key to the Heights. The Russians had built a Great Redoubt on Kourgane Hill, a breastwork that held 12 guns. Slightly higher on the hill was the Lesser Redoubt, whose artillery protected the eastern flank.

There were also Russian cannons on the approaches to the Sevastopol road and guns covering the wooden bridge that spanned the Alma. Most of the 39,000-man Russian Army under Menshikov was positioned around Telegraph and Kourgane Hills.

Only one battalion of the Minsk Regiment guarded the West Cliff because the Russians considered it too steep to climb. The officer commanding there, General V.I. Kiriakov, boastfully told the prince that his battalion alone could tackle any two allied divisions. There were a few scattered stone walls on the north riverbank, and terraces held vineyards that were heavy with unharvested grapes. The stone walls were a double-edged sword since they might provide cover as well as impede an enemy advance. The village of Bourlick was on the north bank, a cluster of 50 houses that was ideal cover for Russian skirmishers.

After the skirmish, the allies made camp for the day, quickly gathering fuel to make their evening dinners. As night fell, hundreds of watch fires twinkled and danced like a carpet of stars. The overall British commander, General Fitzroy Somerset, Lord Raglan, took the opportunity to consult with his French counterpart, Marshal Jacques St. Arnaud. Raglan was an excellent staff officer but incompetent to lead an army. He had served as military secretary and aide-de-camp to Arthur Wellesley, the first Duke of Wellington, during the Napoleonic Wars, and he had been chosen to command the British troops in the Crimea because of his association with the Iron Duke. Wellington was one of the finest soldiers Britain ever produced, and with his passing in 1852 Raglan seemed a natural successor.

Unfortunately, little of Wellington’s genius rubbed off on his protégé. For all his faults, Raglan did occasionally have some flashes of common sense, if not brilliance. He was not in favor of the Crimean campaign since he felt that the British Army was woefully unprepared for such a campaign. The British government ignored his protests. Nevertheless, Raglan was the soul of tact when he met with St. Arnaud on the evening of September 19. The French commander was ill, the feverish ravages of cholera marking his face and giving his eyes an odd cast. The marshal laid out a battle plan for the next day, and Raglan politely concurred with little comment. Speaking in a mixture of English and French, St. Arnaud explained that the French would cross the Alma River and attack where the Russians least expected—the precipitous West Cliff. Warming to the subject, St. Arnaud said the cliff was lightly defended and since it was at the mouth of the Alma, near the sea, the French would have the additional support of naval covering fire.

In St. Arnaud’s scheme, the British would divert Russian attention by attacking Telegraph and Kourgane Hills. With any luck, Raglan’s army might swing east and roll up the Russian right as the French—once they climbed the heights—rolled up the Russian left. Raglan assured St. Arnaud of British support but said little else. The attack began the next afternoon, with a French assault in echelon. Bosquet’s division led the way, crossing the river mouth by means of a sandbar and scrambling up the steep cliffs. Canrobert’s and Prince Napoleon’s troops joined the fray, but the attack stalled because the treacherous tracks up the cliffs were too steep for artillery, and the French preferred to attack with artillery support.

“We Are Being Massacred!”

The British advanced slowly, waiting for the French attack to prosper before going in themselves. The British first line consisted of Evans’s 2nd Division and the Light Division. Behind them the 1st Division (Highland Brigade and the Guards) stood in support. All other British troops were held in reserve. The British marched in column, but when they got within range of the Russian guns across the river, they deployed into line. They were told to lie down, which lessened the chance of being hit by a rampaging cannonball. Nevertheless, the artillery fire was so heavy that casualties began to mount. The redcoats endured the hail of shot and shell for at least 20 minutes, keeping their courage up by giving names to the Russian guns. A French courier galloped up to Raglan, bringing St. Arnaud’s request for help and adding with typical Gallic overstatement, “We are being massacred!” It was time to advance—anything was better than the nerve-wracking bombardment.

The Light and 2nd Divisions moved out. As they did so, the Russians put Bourlick village to the torch. Crackling flames leapt high into the sky, and dense clouds of smoke cast a pall around the immediate area. The acrid smoke and flames threw the 2nd Division into temporary confusion, with one battalion going to the right of the village and the other going left. The once orderly lines bunched up, and the situation was made worse by the Light Division inadvertedly coming in at a slight angle, so that some elements bumped into their colleagues from the 2nd Division.

Some grenadiers crossed the Alma via the still intact wooden bridge, but the river was only around four feet deep on average, and most were able to wade across. The 95th Foot and Royal Welsh Fusiliers became mixed up on the opposite bank, where the steepness of the slope on the Kourgane Hill ironically afforded some protection from Russian cannonballs. But victory would not be gained by sheltering under a lip of ground, and before long the redcoats set off again through a storm of canister and grapeshot. Their advance seemed irresistible, and as they surged up the hill the Russian gunners in the Great Redoubt ceased fire and began to limber up their guns in a frantic effort to escape.

As the Royal Welsh Fusiliers (23rd Foot) poured over the lip of the Great Battery entrenchment, color bearer Lieutenant Harry Anstruther was felled by a Russian bullet. Sergeant Luke O’Connor grabbed the Queen’s colors from the lieutenant’s dead hands and planted the banner in the redoubt, an act for which O’Connor was awarded the Victoria Cross. The redoubt was now in British hands, and two Russian guns had been taken in the bargain. But a counterattack was sure to come, and the nearest British help was the Duke of Cambridge’s 1st Division, which had not yet crossed the Alma. Cambridge was 35 years old, the only divisional commander not to have served in the Napoleonic Wars 40 years earlier. If some of the other British generals were too old in some respects, Cambridge was too inexperienced. The duke was indecisive, uncertain of what he should do. He asked a befuddled subordinate, Brig. Gen. “Gentlemanly George” Buller, for advice. “Why, your Royal Highness,” Buller replied, “I am in a little confusion here—you had better advance, I think.”

In the meantime, the British soldiers holding the Great Redoubt were threatened by a huge Russian column composed of the Vladimir Regiment. Some of the British officers gave the command to shoot, but at least one other officer yelled, “Do not fire—they are French!” Confusion reigned, and a bugler sounded the call to retire. Outnumbered and with conflicting orders, the British abandoned the hard-won redoubt.

The Vladimir Regiment lurched forward to the redoubt, then halted to wait for the Kazan Regiment to come up in support. While they waited, a Russian officer glanced in the direction of Telegraph Hill and saw a small cluster of what looked like British staff officers. They seemed like a mirage because they were well behind Russian lines. It seemed impossible—yet the waving white plumes of their cocked hats confirmed that they were indeed British.

When the fighting started, Raglan had decided to go forward and seek a good vantage point from which to watch the coming action. When he first started out he was accompanied by a horde of hangers-on, men from the Commissariat or Medical Corps who wanted to see some of the action as spectators. They grew to perhaps 60 riders, until they were blocking the view of Raglan and his staff. He let them stay, explaining with a twinkle in his eye: “You know, directly we get under fire, those obliged not to remain will depart. You may rely on it.” Sure enough, a Russian round shot fell short, then bounced up and flew over the heads of the assembled spectators. True to Raglan’s prediction, the hangers-on scattered like a bunch of scared rabbits.

The British commander in chief and his staff crossed the Alma, surprising some French troops from Prince Napoleon’s command who had gained the high ground. In fact, the French had largely scaled the cliffs and were making good progress in pushing back the Russians. Raglan and his party stopped on a spur that jutted out from Telegraph Hill just below the summit. It was a great vantage point, although it was risky to be behind Russian lines and cut off from most of the British Army. From Telegraph Hill, Raglan could observe events but do little to control or influence them. Raglan was literally out on a limb—yet some good did come out of it. “If they can enfilade us, we can enfilade them,” he reasoned, and he ordered up a battery of horse artillery to the site. It was difficult to get guns up the slopes, but once two cannons were in place, they fired on the Russian causeway batteries that guarded the Sevastopol road and were shredding the advancing British infantry.

When the Russian artillerymen found they were being bombarded in flank, they limbered up and withdrew to a new position to the rear. Unfortunately for the Russians, the new sites were too far back, neutralizing any advantage they had in firepower. Meanwhile, the Guards had waded across the Alma, the Highlanders just behind them and to their left. The Grenadier Guards were on the right, the Scots Fusilier Guards in the center, and the Coldstream Guards on the left. They were the flower of the British Army, protectors of Queen Victoria herself, formidable in their towering bearskin caps.

The Vladimir Regiment poured a heavy fire into the survivors of the 23rd Foot, who were holding a position just below the Great Redoubt, causing them to retreat down Kourgane Hill. Gaining momentum as they went down the slopes, they crashed into the advancing Scots Fusilier Guards, disordering their lines and sweeping them away. Queen Victoria had a love of Scotland and was partial to the Scots Fusilier Guards. The Coldstream and Grenadier Guards, knowing this, couldn’t resist chiding their departing comrades: “Shame! Shame! What about the Queen’s favorites now?”

Now there was a gap in the Guards line, and a captain of the Grenadiers ordered his company into a right angle. The Guards reformed in a kind of L formation, a gaping ring of fire that the Russians unwittingly ran into. Volley after disciplined volley cut into the Russian ranks with terrible effect. Once again, British rifle muskets spat minié balls with deadly accuracy. The czarist troops still carried smoothbore muskets, which could not effectively reply except at close range. Decimated by the hail of British gunfire, the Russians withdrew up the slopes.

Routing the Russians

Some 10,000 unbloodied Russian troops moved forward to try to regain the initiative, but they ran headlong into the Highland Brigade, Celtic warriors renowned for their fierce courage on the battlefield. The men in the 42nd (Black Watch), 79th, and 93rd Highlanders were led by Campbell himself. An officer of the 42nd later provided some details of the Highlander odyssey. Before they crossed the river, the Black Watch passed some vineyards, and as they marched the sturdy Celts helped themselves to bunches of grapes. The Alma was shallow—about knee high—although some Highlanders encountered deep pockets where the river rose to chest level.

Once across the river, the Highlanders were subjected to accurate artillery and rifle fire. The Russian artillery was helped by range markers that had been pounded into the ground at intervals. Shaking off the water from their kilts as best they could, the Highlanders reformed and ascended the hill, firing as they went. This could be done only by the best troops, and the Celts proved their worth. The Highland Brigade advanced in two ranks, literally a thin red line nearly 2,000 yards wide. The Russians were incredulous, scarcely believing their eyes. There were two large columns of Russian infantry in the vicinity—the Sousdal Regiment, wearing spiked helmets, and the Kazan Regiment, in forage caps. The Sousdal Regiment tried to take the 42nd in flank – but was met by the 93rd and 79th in echelon. The steady, relentless Highland volleys began to take effect, and the Russian columns wavered, then broke and started to fall back. The Guards retook the battered Great Redoubt, while the 93rd Highlanders swept all enemy soldiers away from the rear of the redoubt, urged on by Sir Colin in his Scottish accent, “We’ll hae nane but Hieland bonnets here!”

The Russian withdrawal became a rout. There was nothing to do but seek the safety of Sevastopol. Menshikov seemed in a daze, unable to comprehend the extent of the debacle. He had promised to hold the Alma Heights for three weeks; he hadn’t even held for three hours. As his soldiers steamed to the rear, Menshikov called out that it was a disgrace for a Russian soldier to retreat. The prince did not seem to realize he was to blame for the galling defeat.

The allied victory was won, and by the time French Zouaves had planted their tricolors on the top of Telegraph Hill, St. Arnaud was convinced that the French had won the Battle of the Alma almost unaided. He said as much in a dispatch to Paris, and only his death from cholera a few days later prevented bad feelings from festering between the allies, who had lost 3,342 dead and wounded. The Russians lost almost 6,000 men, the higher casualties stemming in part from British tactics and the deadly accuracy of the allied rifle-muskets.

A great opportunity was lost in the aftermath of the battle. St. Arnaud had wanted to push on immediately in hopes of taking Sevastopol while the Russians were off balance and reeling from defeat. Raglan refused, stating that there were 3,000 or so wounded British and Russians to take care of, and that they were three miles from the sea and their transport ships. The British commander was also anxious to do a flank march and take Balaklava, the best possible harbor in the area.

Hindsight evidence suggests that St. Arnaud was right. Sevastopol bristled with guns, but its defenses were still incomplete. There was indeed a chance that the allies could have taken the naval base by an all-out attack. On the other hand, Raglan was right in wanting a safe harbor to funnel in men and supplies for an extended siege. He could not have known how vulnerable Sevastopol was at that time. As it was, the Battle of the Alma was only the curtain-raiser to a protracted, bloody, and criminally mismanaged campaign. Alma, like the later fight at Inkerman, was a soldiers’ battle, where the courage and fortitude of the rank and file redeemed at least partially the blunders and sheer incompetence of their leaders.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments