By John Brown

In the 1700s, the Spanish empire in the Caribbean was a lucrative trade monopoly directed from Madrid, with Cadiz designated as the official port for trade to and from Spain and its colonies. Cadiz was also the collection point for the king’s duties on all trade to the New World colonies. Foreigners were banned from trading directly with the Spanish colonies; any foreign ship found trading with them was considered to be smuggling and was seized together with its cargo. The ban was enforced by the Guarda Costa, or coast guard, a flotilla of well-armed ships that could outsail and outgun any heavily laden merchant ship.

Jenkins Loses His Ear

Under the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 that ended the War of the Spanish Succession, Great Britain received a 30-year asiento, or contract right, from Spain. The asiento was in two parts, the Asiento de Negros, which allowed Britain a monopoly to supply 5,000 slaves each year to the Spanish colonies, and the Navio de Permiso, which permitted a single British ship to take 500 tons of trade goods to the annual trade fair at Porto Bello. The British government granted a monopoly for both of the agreements to the South Sea Company. But other British merchants and bankers also wanted access to the lucrative Spanish markets of the Caribbean, and Spanish colonists in turn desired British-made goods. The result was a thriving black market in smuggled goods between industrious merchants in both countries.

In an effort to curb British smugglers, Great Britain in 1729 granted Spain the right to stop and search British ships in Spanish waters to ensure that the terms of the agreements were being respected. But the smuggling continued, and the Spanish continued to board and seize British ships and take their crews prisoner, often torturing them for good measure. This led to a swell of anti-Spanish sentiment in Great Britain.

In April 1731, the East India Company ship Rebecca, captained by Robert Jenkins, was on a voyage from Jamaica to London when she was becalmed off Havana, Cuba. Spanish officials from the coast guard sloop San Antonio, captained by Julio Leon Fandino, boarded and searched the English ship. The cargo was found to be legal; it was sugar. Nevertheless, the Spaniards attempted to make Jenkins reveal any contraband or valuables he might have hidden on the ship, hoisting him up the mast three times by his neck and throwing him down a hatch. Fandino then “took hold of his left ear and slit it down with his cutlass and another coast guard took hold of it and tore it off.” Fandino reportedly gave the ear back to Jenkins, saying, “Go, and tell your King George that I will do the same to him if he dares to do the same as you.”

That Jenkins lost an ear, probably as reported, was true enough, and seven years later, in March 1738, he displayed his preserved ear when he was called to appear in the House of Commons in London, reporting that his ear had been cut off by the Spanish coast guards who boarded his ship, pillaged it, and set it adrift. This and other reports of Spanish atrocities heightened the war fever that was building inside Great Britain, both in Parliament and on the streets. “Jenkins’ ear” became a catchword, slogan, and rallying cry—a gruesome atrocity that was easily remembered among the many atrocities committed by the Spanish on British merchant seamen in the Caribbean.

The controversy disguised the fact that the British were the main offenders in the lucrative illicit trade with the colonies and illegal logging efforts on the coast of Honduras. For years British ships, foremost among them the powerful and privileged South Sea Company, had carried on an extensive trade with the silver-rich Spanish colonies, sometimes with the connivance of corrupt Spanish colonial governors and officials, depriving the king of Spain of his rightful royal duties. Over the years, British merchants had lost many ships and cargoes to the Guarda Costa, including some ships carrying legal cargoes.

The Border Dispute Between Georgia and Florida

In addition to smuggling in the Caribbean, another festering issue between Great Britain and Spain concerned the border dispute between British-controlled Georgia and Spanish Florida. Resolution of both issues was aggravated by patriotic bravado, the clamor of public opinion, and the personal honor of the interested monarchs, George II of England and Philip V of Spain.

There was no easy answer to the question of the boundary between the colony of Georgia, founded in 1732 by James Oglethorpe, and Spanish-owned Florida. The boundaries of all the colonies were only sketchily set down and were open to argument. After a number of skirmishes and mutual accusations, Oglethorpe and the Spanish governor of St. Augustine agreed to maintain peace between them until their respective governments made a definitive boundary decision. While they waited, there were rumors of invasions by either side, adding to tensions between the two powers.

52 Merchant Ships Taken and Plundered

Negotiations continued between the two governments to resolve what constituted legal trade and what was smuggling and to assess the loss to Great Britain from the depredations of the Guarda Costa and the loss to Spain from British smuggling. Claims and counterclaims went back many years; they were time consuming to investigate and difficult to prove. Britain’s chief minister, Sir Robert Walpole, was dedicated to the avoidance of war. So were some of the Spanish. But many powerful British politicians were losing patience with the Spanish, including King George’s secretary of state, the Duke of Newcastle.

In August 1737, two more British ships were boarded by the Guarda Costa near Havana. The only contraband found on board was a few logs from Honduras, but the ships were taken into Havana with their colors at half-mast and the British flag lowered. Crowds of jeering people met the crews, who were imprisoned and allegedly kept as slaves. Back in Great Britain there was a huge outcry over the supposed Spanish insult to the flag and the British subjects taken as slaves.

London merchants, including the South Sea Company, drew up a list of 52 merchant ships taken or plundered by the Spanish in the Caribbean and claimed there were many more. The list, although suspect, was widely publicized, adding to the public furor against the Spanish. In October, the merchants presented the king with a petition asking for action on the alleged depredations by the Guarda Costa. The king in turn demanded a strong response from his government; for him the episodes were personal insults. The government remained divided over what to do.

“Dissatisfaction With Repeated Injuries and Provocations”

In 1738, the Duke of Newcastle sent Spain a demand for a new treaty setting out rules for the proper search of trading ships and defining exactly what constituted contraband. At the same time, he instructed his ambassador in Madrid to advise the Spanish government of Britain’s “dissatisfaction with repeated injuries and provocations” in the Americas and the Caribbean, adding that “nothing but a full satisfaction for what is past and security from the like abuses for the future can put an end to the general uneasiness and resentment.”

Negotiations dragged on into 1739, centering on the exact figures for losses by both sides. Finally, after prolonged dickering and many compromises, it was decided that Spain owed the British crown 95,000 English pounds, while the South Sea Company owed the Spanish monarch 68,000 pounds for the nonpayment of taxes on slaves delivered to Spanish colonies under a prior agreement and for the company’s fraudulent trade with the colonies. A new agreement, the Convention of the Pardo, was drawn up and sent to the respective governments for ratification.

When the convention was introduced into the British Parliament for debate, it was greeted with much argument and opposition. The South Sea Company immediately denied that it owed 68,000 pounds to the Spanish crown and refused to pay. It was decided that everything relating to the company should be taken from the convention and looked at as a separate issue. When the terms of the convention reached the streets of London and Madrid, they caused yet another popular uproar.

In London, debate on the convention dragged into late May, swinging one way and another as powerful individuals, interest groups and lobbyists added their arguments. Then the British government was advised by Spain that since Rear Admiral Nicholas Haddock’s fleet was operating in the Mediterranean King Philip would not pay the 95,000 pounds he owed Britain. This refusal to pay effectively ended discussions between the two nations.

War Breaks Out

In the British press and among the people, opinion swung toward war and how it should be conducted. The king’s cabinet sent secret orders to Haddock, telling him that as soon as hostilities began he was to blockade Cadiz and “commit all kinds of hostilities at sea.” He was ordered to intercept and capture two Spanish treasure ships known to be sailing from the Caribbean to Cadiz.

Admiral Edward “Old Grog” Vernon, British naval commander in the Caribbean, was also alerted to watch out for the two treasure ships. Their capture, it was thought, would compensate Britain for the costs of the negotiations and the preparations for war, with enough left over to cover merchants’ claims against Spain. However, in August the treasure ships, having been warned that British warships were waiting for them near Cadiz, changed course for Santander, where they successfully unloaded cargo worth 7 million pounds.

The loss of treasure encouraged warmongers in Parliament and the cabinet to shout even louder, drowning out Walpole and his followers, who were still trying to revive the Convention of the Prado in the hope of avoiding all-out war. But King George, as he put it, decided to “pursue hostile measures for doing himself and the nation justice,” and Newcastle, bypassing Walpole, drafted a declaration of war. A state of hostilities with Spain was declared on October 23, 1739.

Victory at Porto Bell: “Rule Britannia”

Spanish trade in the Caribbean flowed through four main ports: Vera Cruz in present-day Mexico; Cartagena de Indias in the colony of New Granada, now Colombia; Porto Bello in Panama; and the main port through which all the trade came, Havana. The British war plan was to capture Havana first, since only the Cuban capital had the necessary facilities to build, repair and refit ships that were essential to keeping a fleet operating in the Caribbean.

Porto Bello was a silver-exporting town and naval base on the coast of Panama. Following the failure of a British naval force to take it in 1727, an action in which Vernon had taken part, the admiral had repeatedly claimed that he could capture Porto Bello with just six ships despite criticism that the number was far too few. Vernon was an advocate of small squadrons hitting hard and moving fast, rather than larger, slower moving expeditions that were prone to heavy losses through disease and natural attrition.

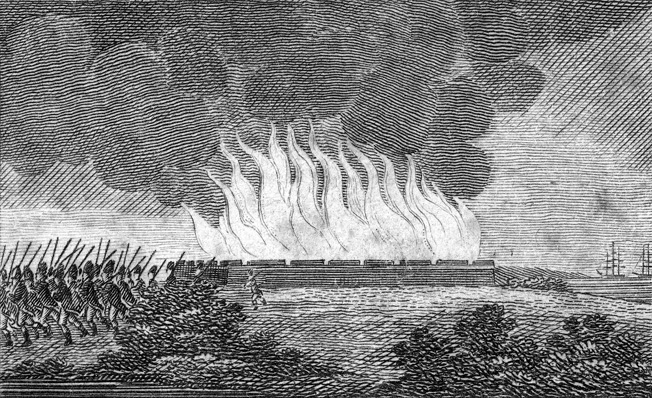

In command of the Jamaica station, Vernon organized an expedition of six ships of the line and sailed for Porto Bello, arriving off the port on November 20. Porto Bello’s defenses were weak, and Vernon besieged them for just a day before the Spanish garrison surrendered. Vernon’s force then occupied the town for three weeks, destroying the fortress, the port, warehouses, and other key buildings—in essence, ending the settlement’s function as a maritime base and severely damaging its economy.

In Great Britain, the victory at Porto Bello was greeted with jubilation, and in 1740, at a dinner in London in honor of Vernon, the song “Rule Britannia” was performed in public for the first time. The name Porto Bello was frequently used to commemorate the battle, as in Portobello Road in London and Porto Bello, Virginia. Vernon was promoted to full admiral, and his name was remembered in many ways, including Mount Vernon, the future estate of George Washington. The destruction of Porto Bello forced the Spanish to change their trading practices. Rather than trading at centralized ports and using a few large treasure ships, they began using a larger number of smaller ships in convoy, trading at a wide variety of ports.

The British Caribbean Expedition

In January 1740, Georgia Governor James Oglethorpe marched into Florida with Georgia and Carolina troops. They captured two Spanish forts, San Francisco de Pupo and Picolata, on the San Juan River and besieged St. Augustine for several weeks before returning to Georgia.

Meanwhile, preparations to mount a large-scale British expedition to the Caribbean were very slow. The expedition was to be commanded by General Lord Cathcart and escorted by 25 warships under the command of Admiral Sir Chaloner Ogle. The cabinet did not specify the local objectives of the expedition, which were left to the judgment of the field commanders, but the overall objective was the gold and silver of the Indies.

That August, 6,000 soldiers embarked in troop transports and sailed off, eventually straggling into the Caribbean to rendezvous in Jamaica a few days before Christmas. Cathcart had died along the way; Brig. Gen. Thomas Wentworth, who had no previous combat command experience, replaced him. Diseases such as typhus, scurvy, and dysentery claimed many casualties among the soldiers and sailors. By January 1741, the land forces had suffered 500 dead and 1,500 sick. In Jamaica, 300 African slaves, called Macheteros, were added to the expedition as a work battalion.

Jealousies and arguments over the expedition’s main goals arose among the field commanders and further slowed the progress of the campaign. Vernon’s view prevailed, that Cartagena de Indias, principal gold trading port and naval base in the colony of New Granada, should be the first target. Havana, Vernon believed, was too well defended to attack.

Capturing the Manila Galleon

In September 1741, Commodore George Anson set sail from England with six warships and two supply ships for Cape Horn and the Pacific. His crews were old and sick and his marines raw and untrained, Anson complained. They could not even be trusted to fire their weapons. Many died of disease before reaching the Pacific, and many more were sick and in no condition to launch any sort of attack, so Anson reassembled his ships in the Juan Fernandez Islands to allow the crews and marines to recuperate.

Anson’s orders were to attack the Spanish along the Pacific coasts of South and North America. In particular, he was directed to capture the Spanish treasure galleon that sailed each year from Manila to Acapulco. After resting his men, Anson moved up the coast of Chile, raiding the small town of Paita but reached Acapulco too late to intercept the Manila galleon. He retreated across the Pacific and ran into a violent storm that forced him to dock for repairs in Canton.

The following year Anson made another attempt to intercept the Manila galleon. On June 20, 1743, although greatly outmanned and outgunned, he captured the galleon off Cape Espiritu Santo. It was filled with treasure and gold coins to the value of more than 800,000 English pounds.

Anson sailed for home, arriving in London in June 1744, more than three and a half years after he had set out, having circumnavigated the globe. Only one of his ships, Centurion, and less than a tenth of his men survived the expedition. Nevertheless, Anson’s achievements led to his appointment as First Lord of the Admiralty.

The Battle of Cartagena de Indias

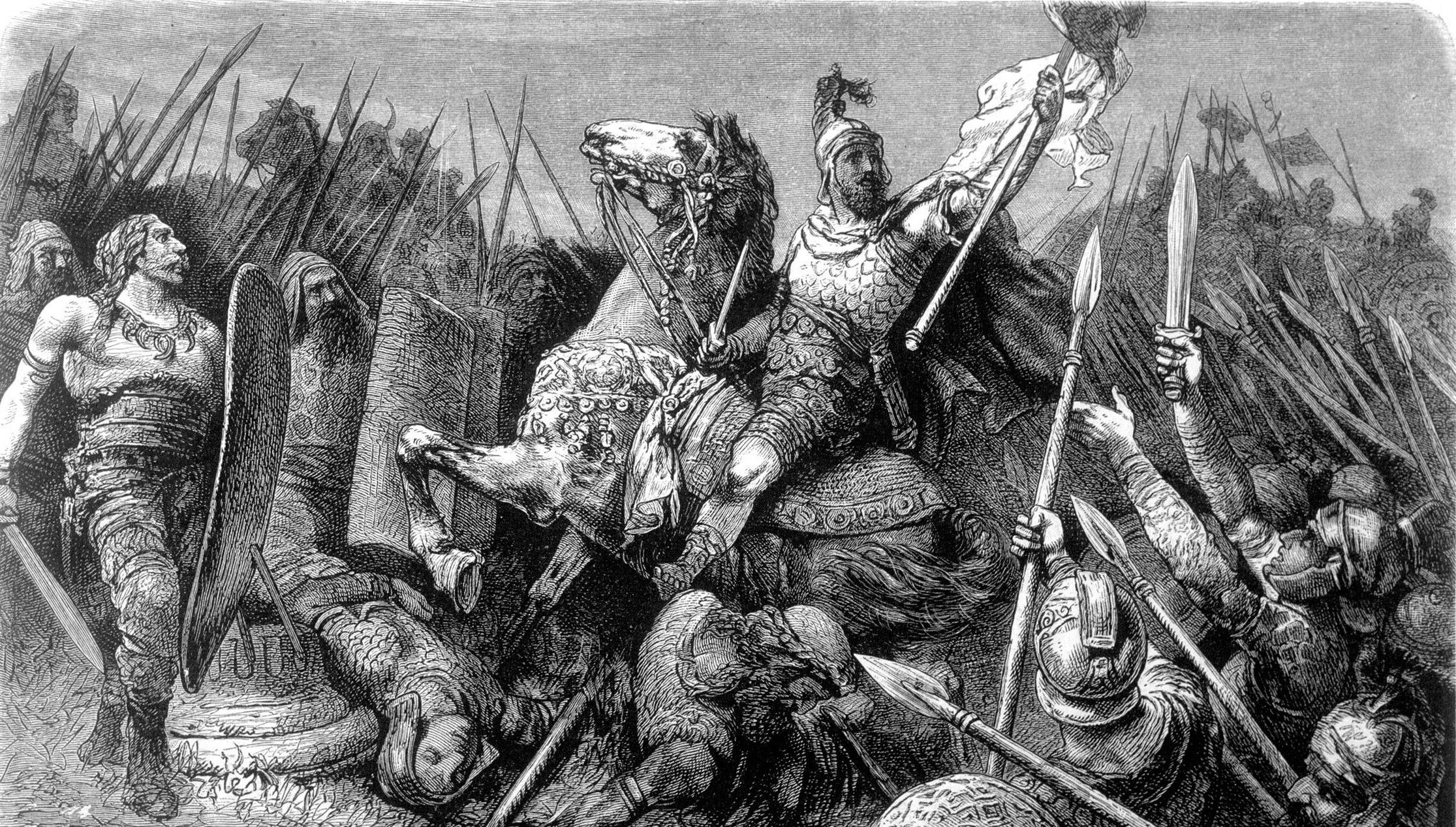

In the meantime, Vernon’s plans for the assault on Cartagena de Indias were hampered by inefficient organization, rivalry with the commander of the land forces, and the logistical problems of mounting and maintaining a major transatlantic expedition. To make matters more difficult, Cartagena’s fortifications were strong and the Spanish commander, Admiral Blas de Lezo, was a skilled and experienced strategist.

Vernon’s expedition arrived off Cartegena on March 4, 1741. Wentworth commanded the land forces, and Vernon commanded the sea forces. Some 3,600 American colonial marines already had been transported from New York to Jamaica, landing there in December 1740 under the command of Colonel William Gooch. The Americans joined the expedition for the attack on Cartagena. By this time, the Navy had lost so many sailors from epidemics that one-third of the land force was needed to fill out the crews.

Cartagena, a rich city of over 10,000 people, was strongly defended under the able command of Lezo and the Viceroy of New Granada, Sebastian de Eslava. It was fronted on one side by the ocean, but the shore and surf were so rough that they precluded any attempt to approach the city from the sea. Access to the city was through two channels, Boca Grande, which was too shallow for ocean-going ships, and Boca Chica, the only deep-draft passage into the harbor. The passage ran between two narrow peninsulas and was defended on one side by Fort San Luis, with four bastions having 49 cannons, three mortars, and a garrison of 300 soldiers. A boom stretched from the island of La Bomba to the southern peninsula on which was located Fort San Jose with 13 cannon and 150 soldiers. Also in support were six Spanish ships of the line.

The British bombarded the forts for a week then landed 300 grenadiers and artillery near the Boca Chica channel. The Spanish defenders of two small, nearby forts were driven off by three ships of Chaloner Ogle’s fleet, which suffered 120 killed and wounded. The ships were also damaged by cannon fire from Fort San Luis.

The grenadiers were followed ashore on March 22 by the whole of the British land forces—two regular army regiments and six regiments of marines. Only 300 Americans went ashore; most of the American troops had been dispersed to serve aboard ships of the line, replacing Vernon’s lost sailors. After the army made camp, the Americans and Macheteros constructed a battery, and its 24-pounder guns began battering Fort San Luis. A squadron of five ships attempted for two days to batter the fort into submission but made no progress, sustaining more casualties. Three of the ships were heavily damaged and disabled.

British artillery, firing night and day for three days, finally made a breach in the main fort. Some British ships engaged the Spanish ships, two of which were scuttled and the other set on fire and captured. The two scuttled ships partially blocked the channel. On April 5, the British attacked Fort San Luis by land and sea, with infantry advancing on the main fort while the Spanish garrison retreated to inner fortifications. The following week the British entered the harbor at Boca Chica, losing an additional 120 killed and wounded while a staggering 250 died from yellow fever and malaria and 600 more were hospitalized.

Assault on Fort Lezaro

With the capture of Fort San Luis and other outlying fortifications, the fleet passed through the Boca Chica channel into the harbor at Cartagena. Again the Spanish withdrew, concentrating their forces at Fort San Lazaro and inside the city proper. Vernon goaded Wentworth into an ill-considered, badly planned assault on the fort, an outlying strongpoint of Cartagena. Vernon’s ships cleared the beach with cannon fire, and Wentworth landed at Texar de Gracias.

After the British occupied the inner harbor and captured some outlying forts, Lezo strengthened the last main bastion of Fort Lezaro by digging a trench around it and clearing a field of fire on the approach. Lezo defended the trench with some 650 soldiers, garrisoned the fort with another 300, and held a reserve of 200 marines and sailors. The British advanced from the beach, and after a short fight the Spanish gave way.

The only British engineer with the expedition had been killed at Fort San Luis, leaving no one who could construct a battery to breach the city walls, so the British decided to storm the fort in a night attack on the walls. Such an attack would enable them to assault the northern side of the fort facing Cartagena, since the guns inside the city would not be able to give supporting fire. The southern side had the lowest and most vulnerable walls, and the grenadiers hoped to quickly storm and carry the parapets.

18,000 British Casualties

The attack started late, and the initial advance on the fort was not made until nearly dawn on April 20, by 50 picked men followed by 450 grenadiers commanded by Colonel John Wynyard. They were followed by the main body of 1,000 men of the 15th and 24th Regiments commanded by Colonel James Grant, together with a mixed company from the 34th and 36th Regiments and some unarmed Americans carrying scaling ladders for the fort’s walls and wool packs to fill in the trench. Last came a reserve of 500 marines commanded by Colonel Edward Wolfe.

The column was guided by two Spanish deserters who purposely misled the column from the southern, low-walled side. Wynyard was led to a steep approach, and as the grenadiers scrambled up the slope they were hit by a volley of musket fire 30 yards from the entrenched Spaniards. The grenadiers deployed into line and advanced slowly, firing as they moved. On the north face, Grant was killed and the leaderless troops traded desultory fire with the Spanish. Most of the Americans dropped the ladders they were carrying and took cover, and the ladders that had been brought forward were found to be too short for the troops to scale the wall.

The sun rose, and the guns of Cartagena opened fire on the British. Casualties mounted, and at 8 o’clock a column of Spanish infantry coming from the city threatened to cut off the British attackers from their ships. Wentworth, realizing that the assault had failed, ordered a retreat. The British lost 600 men out of a force of 2,000, with sickness and disease increasing the casualty figure. Wentworth’s land forces were reduced from 6,500 effectives to 3,200 in the period surrounding the attack of Fort San Lazaro.

Cartagena’s strong fortifications and the skill of the Spanish commander, Lezo, were decisive in repelling the attack. Given the overwhelming British force, Lezo planned to conduct a fighting withdrawal that would delay them until the start of the rainy season at the end of April, when tropical downpours would halt campaigning for two months. The longer the British remained crowded on their ships at sea or in the open on land, hunger and disease would claim many more casualties. Lezo was helped by the contempt that Vernon and Wentworth felt for each other, which prevented their cooperation throughout the expedition.

In the end, the fight for Cartagena lasted 67 days and ended with the British fleet withdrawing in ignominious defeat, with 18,000 dead or incapacitated by disease. The British lost a total of 50 ships; another 19 ships of the line were damaged, and four frigates and 27 transports were lost. Of the 3,600 American colonists who had volunteered, lured by promises of land and mountains of gold, most died of yellow fever, dysentery, or starvation. Only 300 returned home, including George Washington’s older brother Lawrence, who renamed his Virginia plantation Mount Vernon after the admiral.

In the early days of the expedition, when the Spanish were retreating, Vernon sent an ill-advised message to King George informing him of a forthcoming victory. Eleven different commemorative medals were minted in London to celebrate the victory. After news of the defeat reached London, all the medals were removed from circulation and the king forbade the news from being disclosed. Following the defeat, Walpole’s government collapsed.

From Jenkins’ Ear to the Austrian Succession

The British undertook several other attacks in the Caribbean with little better success. In July, Vernon launched an invasion of Cuba, but he refused to land troops any closer to Santiago, the first objective, than Guantanamo Bay. The landing proved to be too far away and the invasion was aborted.

In January 1742, 3,000 troops arrived from England to replace the losses at Cartagena. Meanwhile, the Spanish attempted to seize the British colony of Georgia. Some 2,000 troops landed on St. Simon’s Island, but James Oglethorpe and local forces defeated the invaders at Bloody Marsh and Gully Hole Creek and forced them to withdraw. Border clashes between Florida and Georgia continued for several years, but there were no further major operations on the American mainland by either nation.

The Caribbean campaign ended in May 1742. By then, a majority of the British force had died from combat or sickness. Vernon and Wentworth were recalled to England in September, and Ogle took command of a fleet that had less than half its sailors fit for duty. By then the odd little War of Jenkins’ Ear had merged into the much larger War of the Austrian Succession, a dispute over the succession to the Austrian throne that grew to involve all the main European nations and their forces overseas. Captain Jenkins and his missing appendage were forgotten in the ongoing rush of events.

My sixth Great Grandfather (Timothy Pumphrey) supposedly fought and died in the Battle of Jenkins Ear. I have reviewed some materials developed by historians and genealogist. They speculate that he was buried at sea in the Caribbean in 1742. He was a British Colonial from Anne Arundel County, Maryland and left behind his wife (Mary Pumphrey) of only 9 years. Are there any records / archives of deaths / casualties from this period that I could research to validate any of this information?