By Marc G. Desantis

The early years of Rome’s second war with Carthage were some of the darkest the Republic had ever known. Since the beginning of the war in 218 bc, when the Carthaginian general Hannibal Barca had launched the conflict by attacking Rome’s ally Saguntum in northeastern Spain, the first years of the Second Punic War had been miserable for the Romans.

Roman forces had been smashed time and again by the brilliant tactics employed by Hannibal. A dreadful sequence of defeats marked Rome’s encounter with the Carthaginian general. At Trebia River, Lake Trasimene, and most spectacularly and painfully, at Cannae, Roman armies had been crushed. The Roman legions that had proven themselves in battle against all other opponents seemed at a loss to cope with the superb Carthaginian commander.

Stalemate at the Gates of Rome

Schooled in the finest traditions of generalship in the ancient Mediterranean world, Hannibal was nearly invincible. His Roman opponents seemed, in comparison, decidedly unprofessional in their tactics and command structure. Hannibal was clever and insightful, but the Roman commanders he encountered were neither. Their flaws made all the difference in the crucible of combat, costing the Romans tens of thousands of lives. If Rome was to have any chance of winning the present war against Carthage, it would have to find a more battle-worthy commander for its legions.

Hannibal’s success against Roman armies in the field was not equaled by success against the city of Rome. In the aftermath of the devastating victory of Cannae, and with Rome virtually defenseless, Hannibal decided not to march on the city at once, but chose instead to rest his weary troops. Hannibal’s decision not to attack Rome immediately has been criticized for centuries. The reproach levied at the time by Maharbal, his foremost cavalry commander—that Hannibal knew how to win a battle but not how to use the victory—still echoes across the ages. Whether he could actually have defeated Rome in 216 bc is open to conjecture. But for Rome, the unexpected respite allowed the city time to regain a semblance of stability, and Hannibal was subsequently kept at arm’s length.

Hannibal and the Carthaginian army settled down in Italy for a long struggle against Rome and its allies. In spite of the tremendous shocks delivered by Hannibal to Rome’s legions, the Italian confederation, of which Rome was the leader, remained largely loyal to the city. Without Rome’s allies leaving the coalition, Hannibal could not defeat the Romans decisively. For their part, the Romans were unable to force the Carthaginians to leave the Italian peninsula.

Hannibal’s Unbeatable Army

With Hannibal and the Romans occupied in Italy, their counterparts struggled fiercely for the upper hand in the subsidiary theater of Spain. The country had long been a significant part of the overseas mercantile empire controlled by Carthage. As active merchants, the Carthaginians had trading interests all over the western Mediterranean. The expanding Carthaginian presence in Sicily had been one of the salient reasons why Rome and Carthage went to war in the first place in 264 bc. The First Punic War lasted 23 years and saw great losses by both sides.

Many of the First Punic War’s most important battles were fought at sea. Although Rome had not even had a navy worthy of the name at the beginning of the war, by its end in 241 bc, the Romans had defeated the Carthaginians decisively. Carthaginian naval power was broken, and peace was established between the two states. This peace, though, was not to endure. Hard feelings remained on both sides. Among the most irreconcilable was Hamilcar Barca, an eminent Carthaginian general. He passed along to his sons, including Hannibal, an unquenchable hatred of Rome.

With their sea power blunted, Sicily lost, and Sardinia taken from them, the Carthaginians expanded their holdings in Spain. The charismatic Hannibal established good relations with the various warlike Spanish tribes. He honed an army of Carthaginians, mercenaries, and tribesmen into a formidable fighting machine. The Carthaginians often relied on mercenaries to fill the ranks of its armies. The magnetic Hannibal welded the Carthaginians and their Spanish, Numidian, and Gallic mercenaries into a cohesive battle force. The Numidians, in particular, supplied Hannibal with a major advantage over the Romans. Exceptional horsemen, the Numidians combined with Hannibal’s extraordinary military genius to forge a formidable, lethal, almost unbeatable entity.

When the time came, Hannibal led his army across the Ebro, the river that had been the demarcation line between the Carthaginian and Roman spheres in Spain. Hannibal’s move against Saguntum in 218 bc started the Second Punic War. After a difficult and sometimes harrowing march across southern Gaul and into Italy with his army, Hannibal brought massive destruction to the Romans in their homeland.

Even after Hannibal left Spain, the Carthaginians still relied on their holdings there to empower their war effort against Rome. Spain was critical to Carthage both economically and as a source of mercenaries for its armies. The Carthaginians were a numerically smaller people than the Romans and were more oriented toward commerce than war. Carthage needed soldiers for its armies, and Spain provided a large number of fine warriors.

The Young Scipio Volunteers to Lead the Army

The Romans could not leave the rich Carthaginian possessions in Spain untouched. In 216-215 bc, Roman armies in Spain under the command of the brothers Publius Cornelius Scipio the Elder and Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio were able to halt any more Carthaginian troops from leaving Spain to help Hannibal in Italy, thus preventing him from striking another major blow against Rome.

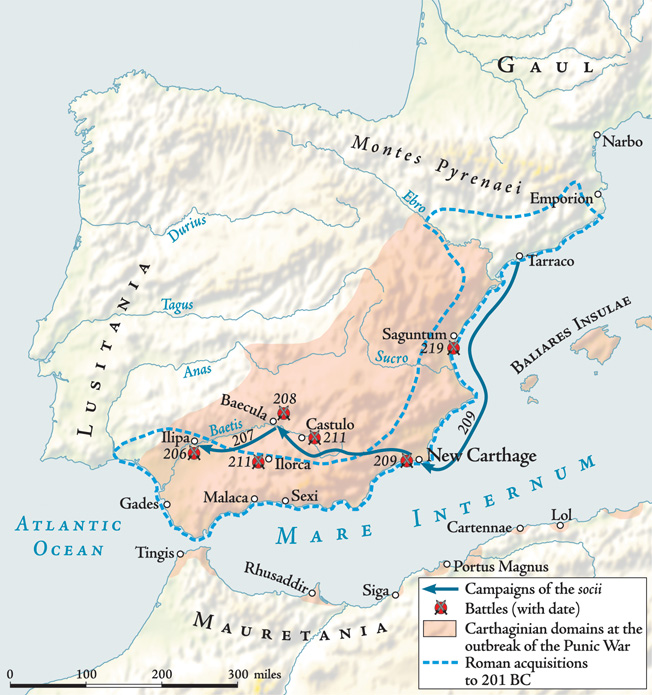

Unfortunately for the Romans, the situation in Spain would soon spin out of control. The Scipio brothers were killed in separate battles near Castulo and Ilorca in southern Spain in 211 bc after being betrayed by their local Celtiberian allies. A third Roman force was ambushed and mauled. Numerous Spanish tribes openly aided Carthage or held themselves aloof from the Romans. Disaster seemed imminent. The Republic needed a general to take command of Roman forces in Spain and keep the Carthaginians occupied.

But the Republic could find no one satisfactory for the position of proconsul in Spain. In 210 bc the Senate decided to hold a special election to determine the new commander. On the day of the election, however, not a single Roman came forward as a candidate for the Spanish command. Ordinary Romans took this reluctance to mean that the war in Spain was a hopeless cause. At this dark moment, 24-year-old Publius Cornelius Scipio, the son of one of the slain Roman generals and nephew to the other, stepped forward and offered his candidacy for the proconsulship. Lacking any other alternative and relieved to have a candidate at all, the assembled citizens unanimously elected Scipio to the post.

Showing himself to be more than a mere callow youth, Scipio held an assembly that spoke to concerns about his age. His speech to his fellow citizens instilled in them a new belief in his abilities and competence. He possessed remarkable physical courage (at age 18 he had saved his father’s life in battle) in addition to a keen intellect. But would the young man prove himself equal to the enormous task ahead in Spain?

The young general readied a force of 1,000 cavalry and 10,000 infantry and sailed from Italy to Spain with a small fleet. He established his base of operations at Tarraco in the northeast of the peninsula. Once there, Scipio wasted no time shoring up the confidence of Rome’s nervous Spanish allies and inspecting the Roman troops already stationed there. Restoring the morale of the Roman legionaries was an intelligent move by Scipio. They were fine soldiers, but they needed a good leader. If Scipio could make good use of the Roman soldiers’ basic attributes—courage, skill with weapons, and collective flexibility in battle—he would stand an excellent chance of victory over the Carthaginians.

Scipio’s Bold Strategy

Opening the spring campaign season in 209 bc, Scipio’s Roman troops marched from their winter quarters; their Spanish allies left their homelands as well. These forces rendezvoused at the mouth of the Ebro River in northern Spain. When all his men had gathered, Scipio spoke to them about his slain father and uncle, with whom many of the troops present had served. The defeats of earlier years were due to the betrayal by Rome’s faithless Celtiberian allies, he said, not because the Romans themselves were inferior soldiers. Scipio reminded the men that Carthaginian arrogance in Spain had alienated many Spaniards and made them more amenable to Roman friendship. The Romans should be confident of victory when they moved south of the Ebro into Carthaginian-dominated territory.

Scipio left behind a force of 3,000 foot soldiers and 500 horsemen to protect the river crossing. With the remaining troops (25,000 infantry and 5,000 cavalry) he crossed the Ebro, his plans for the upcoming campaign unknown to any but himself. Scipio had good reason to be silent. He was prepared to launch a daring strike at Carthage’s most important base on the entire Iberian Peninsula, New Carthage.

Scipio recognized that the Carthaginian forces in Spain, of which there were three main bodies, were dispersed too widely to come to New Carthage’s rescue if he struck rapidly to take the city. Hannibal’s brother Hasdrubal Barca (Hannibal was the eldest of the Barcas) was more than 10 days away from New Carthage. Mago, the youngest Barca brother, was in the far west, in Portugal. Hasdrubal Gisgo, the third major Carthaginian commander in Spain, was also in Portugal, far away from Scipio’s intended target.

Scipio had pieced together a remarkably complete intelligence picture of New Carthage—who was there, what was there, and the overall layout of the city. All of the Carthaginians’ baggage and a large store of military equipment were in the city. Remarkably, the place was lightly garrisoned by a force of 1,000 men. The Carthaginians, Scipio reasoned, did not expect the enemy to attack New Carthage. He would soon make them pay for their laxity.

Taking New Carthage

Scipio ordered his fleet commander, Gaius Laelius, to take his ships to New Carthage, timing his arrival to coincide with the approach of Scipio’s army. Seven days later, the two Roman contingents rejoined at New Carthage. While the fleet imposed itself on the harbor, the legionaries took up positions north of the city. The Romans, showing their skill at battlefield engineering, quickly erected a rampart to protect their army from attack from the rear.

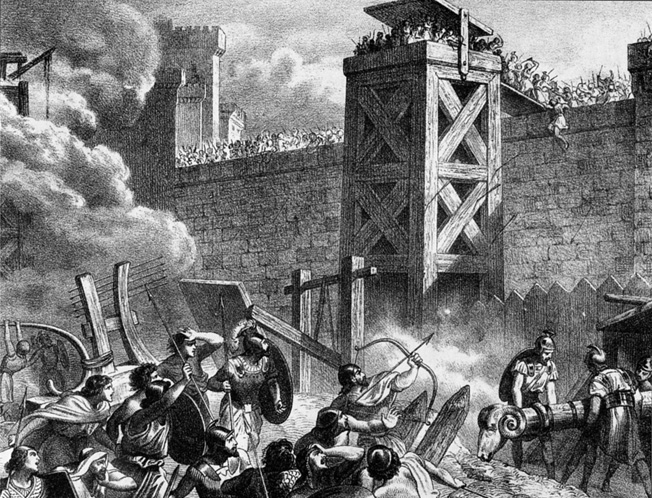

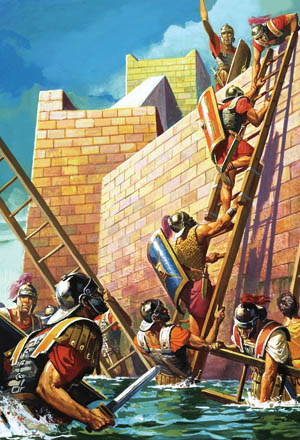

A sortie by the Carthaginian defenders ended badly for them, and the pell-mell retreat to New Carthage spread panic among the men guarding the walls. The guards ran away, leaving their sections unprotected. Scipio, atop a nearby hill, saw the inglorious flight from his vantage point. He immediately ordered his army to ready itself for an assault. With Scipio urging them on, the legionaries quickly made up the ground between their camp and the city, scrambling up the walls via scaling ladders. Meanwhile, the Roman fleet disembarked its soldiers in an amphibious attack, an operation stymied by too many soldiers trying to be the first to land. By this time, the Carthaginians had recovered somewhat from their initial panic and had returned to the walls as the Roman assault began.

Problems hampered the Roman attack. Their ladders were not long enough to surmount the walls, and many became overloaded with soldiers and broke apart. In spite of the setbacks, Scipio’s detailed intelligence gave him another card to play. He knew from fishermen at Tarraco that the lagoon at New Carthage could be crossed on foot at low tide. The tide had already begun to go out, and Scipio took a detachment of 500 soldiers to the lagoon. The Romans crossed the water and climbed the adjacent wall, which had been left unwatched by the defenders, who trusted too much in the natural defense provided by the lagoon. Scipio headed straight for the city gates, which he attacked almost unnoticed by Carthaginian troops locked in battle.

The defenders panicked when they realized they had been taken from behind by an unobserved enemy force. The Romans broke open the gate and scaled the walls. Its situation completely untenable, the Carthaginian garrison quickly gave up.

Winning Over the Tribes of Spain

Scipio had won a prize of enormous strategic value, a vast haul of equipment that included more than 200 siege machines. He handled the aftermath of the victory well, displaying generosity and shrewdness in equal measure. Approximately 10,000 free men had been taken into custody. He allowed all those who were citizens of New Carthage to retain their freedom and possessions. More importantly, certain Spanish hostages had fallen into his hands, and Scipio showed the keen political judgment that distinguishes a great commander from a merely good one. He treated his hostages well, with an eye toward gaining favor with their tribes and detaching them from their allegiance to Carthage. Scipio realized very early that in order to have a realistic chance of defeating Carthage he would have to bring the Spaniards over to his side. He allowed them to return to their families in hopes of sparking a sense of gratitude among them.

Spain was home to three main tribes. There were the native Iberians, people of ancient lineage on the peninsula with a fine military reputation. There were the Celts, who had come from the north and were related linguistically to the Gauls of Northern Europe. As Celts, they were naturally good warriors. Finally, there were the Celtiberians, representing a fusion of the other two tribes. They were tough fighters as well and had proved a mortal threat to the Roman position in Spain with their betrayal of Scipio’s father and uncle.

Scipio further increased his standing with the Spaniards by showing adroit chivalry to his captives. One elderly woman who was related to the prominent Spanish chieftain Indibilis of the Ilergetes tribe was worried about the fate of the young women in Roman custody. She begged Scipio to take care of the women prisoners, among whom were the daughters of Indibilis himself. Scipio assured her that they would be well treated and placed the women in the care of a trusted officer who would see to their safety while in custody.

In another incident, a young woman of exceptional beauty was brought forward while Scipio was examining the Spanish hostages. It soon emerged that she was engaged to a young Celtiberian chieftain named Allucius. Scipio sent for the young man and reunited him with his bride to be. All he asked for returning the woman, Scipio told him, was that he be a friend of Rome, an offer that Allucius willingly accepted. A little later, when the young woman’s parents arrived with a ransom of gold for their daughter, Scipio rejected it for himself and instead gave it to the couple as a wedding gift. Allucius returned to his people, informed them of Scipio’s generosity, and raised a force of 1,400 cavalry to serve with the Romans. The young general’s political instincts had already begun to pay dividends.

From a strategic point of view, the capture of New Carthage had dealt the Carthaginian position in Spain a devastating blow. The preeminent Carthaginian holding in the Iberian Peninsula, named after the mother city herself, was now firmly in Roman hands. Supplying their own troops would be more difficult, and the loss of prestige occasioned by the fall of the city could not help but cause some Spaniards to doubt the Carthaginian cause.

Scipio returned to his base at Tarraco for the winter. In the wake of the fiasco at New Carthage, the Carthaginian commanders in Spain felt a pressing need to take the offensive against the burgeoning Roman presence in the country. The ground had begun to shift ever more in favor of Scipio. Indibilis and his brother Mandonius, the husband of the old woman with whom Scipio had spoken in New Carthage, had left the Carthaginian side and joined the Romans. Another Spanish chieftain, Edesco, had done the same. All believed that Rome was on the ascendancy in Spain.

Carthaginian Defeat at Baecula

Scipio, like the Carthaginian commanders, was intent on seeking battle before the enemy armies could unite into one massive body. The dispersal of the Carthaginian armies gave him valuable time to effect a plan to deal with them separately. In preparation for the beginning of the campaign season in 208 bc, Scipio augmented his army with the enormous stock of heavy weapons seized at New Carthage. His infantry was also reinforced with the sailors and marines from the ships of the fleet, which had little to do now that the eastern Spanish coast was entirely under Roman control.

Scipio once more set out from Tarraco in search of Hasdrubal’s army. Along the way he was joined by the warriors of Indibilis and Mandonius. Hasdrubal’s army was camped near the Baecula River in southern Spain, in a strong position guarded by cavalry pickets. Scipio aggressively assaulted the Carthaginian cavalry right off the march, leaving the enemy little time to prepare. The suddenness of the Roman onset swept the Carthaginians before them, and the Romans pursued them all the way to the enemy camp. Scipio then set up his own camp and waited for morning.

That night Hasdrubal moved his troops back to the security of a flat-topped hill with two plateaus near the Baecula River. The next day, Scipio spurred his troops by pointing out that the Carthaginian army had sought the protection of the hills where they had established their new camp. They were not putting their faith in their courage, he said, but in geography. New Carthage’s walls had been even higher, he reminded his legionaries.

Leaving behind two cohorts of infantry to guard against a sudden enemy sally, Scipio engaged the light infantry posted by Hasdrubal on the lower of the hill’s two plateaus. The Carthaginians hurled their missiles at the Romans, who were hard pressed to maintain their advance up the hill. But as soon as the Romans reached the flat terrain on the lower plateau, they made short work of the lightly armed enemy, who had no hope of standing toe-to-toe with them.

Scipio kept going, aiming for the middle of the Carthaginian line, which was located above the Romans on the upper plateau of the hill. He ordered his second in command, Gaius Laelius, to make his way along the right side of the hill and find a less arduous route to the top. Scipio then moved the rest of the troops to the left, where he discovered his own path to the top. His troops took the enemy in the flank, catching them off guard. In the meantime, Laelius’s soldiers had surmounted the plateau as well, and the Carthaginian battle line was thrown back in disarray. In short order, the Romans were in command of both the hill and the Carthaginian camp.

Carthaginian losses at the Baecula were heavy—8,000 dead and 12,000 taken prisoner by the Romans. Hasdrubal managed to flee with a handful of soldiers and headed north toward the Pyrenees. There he would lick his wounds and rebuild his army for the planned invasion of Italy.

In dividing the spoils of battle, Scipio again showed political shrewdness. He gave 300 captured horses to Indibilis, who had recently come over to the Roman side. Also, a young Numidian captive who was related to the famed Prince Massinissa was returned forthwith to his people. Such clemency would pay dividends for Scipio long after the war in Spain was over.

Defeat of the Celtiberians

In the wake of the defeat at the Baecula, the three Carthaginian commanders in Spain discussed their options. Hasdrubal was almost completely bereft of troops. His brother Mago and Hasdrubal Gisgo both told him that the loyalty of all the Spanish tribes was in doubt. In order to hold onto Spain and prevent more Spaniards from going over to the Roman side, the Carthaginians decided that they would have to get their own Spanish troops out of the theater entirely. All of the Spanish troops in their employ would be transferred to Hasdrubal Barca for service outside Spain. Mago would transfer his troops to Hasdrubal Gisgo and sail for the Balearic Isles (Majorca and Minorca) to recruit mercenaries to serve in Spain. Hasdrubal Gisgo would head for Lusitania, in the far west of the peninsula.

In 207 bc, Hasdrubal Barca began his march to Italy through Gaul, intending to reinforce his brother. This left a deficit of strength in Spain. To compensate, soldiers under the command of another general, Hanno, joined Hasdrubal Gisgo and Mago Barca. Numerous mercenaries from among the Celtiberian tribesmen were recruited as well.

Scipio dispatched his lieutenant Marcus Silanus with 10,000 infantry and 500 cavalry to bring the newly raised enemy army to battle. Rapid marching brought Silanus to the outskirts of the Carthaginian and Celtiberian camps, which were close to one another. The Celtiberian camp, where some 4,000 infantry and 200 cavalry were stationed, was carelessly guarded, and Silanus made it his first target. By a stealthy advance, the Romans were able to close to within a mile before they were spotted.

The energetic Mago had noticed the Roman approach and rushed to get the Celtiberians ready for battle. After establishing a semblance of a line, he hurried them out of their camp, where they were met by a shower of Roman spears. Close combat ensued, and the Romans got the better of it, killing large numbers of Celtiberians. Mago fled with some 2,000 infantry and cavalry and joined Hasdrubal Gisgo near Cadiz, but the luckless Hanno and many other men were taken captive by the Romans. The Celtiberians who managed to escape the disaster trudged home and did not take further part in the war.

Silanus had done well, and his victory spoiled the latest Carthaginian attempt to drive out the Romans. Scipio still wanted to come to grips with Hasdrubal Gisgo, but Hasdrubal wanted to avoid a clash and, after parceling his men among the various towns of the south of Spain, hung back on the defensive. Scipio sent his brother Lucius Cornelius Scipio to attack the city of Orongis, which was garrisoned by a small Carthaginian force. Orongis quickly fell, but campaigning season came to an end and Scipio sent the legionaries into winter quarters and returned to his base at Tarraco.

45,000 Spanish Recruits

The focus of attention now fell squarely upon northern Italy, where Hasdrubal Barca made his attempt to join his brother Hannibal. Scipio sent reinforcements to the aid of the Italian-based Roman forces. In a dramatic battle alongside the Metaurus River, the Romans defeated the Carthaginians, dashing any enemy hopes of strengthening Hannibal. Hasdrubal himself was killed and his severed head thrown into Hannibal’s camp as a grim notice of his brother’s demise.

Scipio was confident that the end was near for the war in Spain. He decided to seek out Hasdrubal Gisgo for a climactic action that would crush the Carthaginian army once and for all. For his own part, Hasdrubal Gisgo did not remain idle. Alongside Mago, he recruited an enormous army of 50,000 infantry and 4,500 cavalry in western Spain. They were prepared for one last throw of the dice in the hopes of retrieving their position in Spain and altering the fundamental balance of the war.

When Scipio learned of the massive enemy army, he paused. He knew that he would have to raise more troops from among the Spaniards to contend effectively with the Carthaginians. But the old bugbear of doubtful Spanish allegiance reappeared. His father and uncle had met their demise when the Celtiberian troops on whom they had relied defected to Carthage. If he allowed too many Spaniards into his own army, he risked a devastating loss himself if they suddenly switched sides again. Scipio therefore gathered only a modest number of Spanish recruits for the new campaign, approximately 45,000 in all.

Battle at Daybreak

The Romans halted in the vicinity of Ilipa. Carthaginian and Numidian cavalry struck as they were erecting their camp. After a sharp fight, the Romans drove off the Carthaginians, and for the next few days a skirmish was fought across no-man’s-land by the light infantry and cavalry of both armies.

Hasdrubal felt confident enough after these raids to lead his army out of camp. The Carthaginians formed a battle line, and the Romans did the same. A staring contest of epic proportion ensued, with neither army taking any step to assault the other. Over the course of several days, each army dutifully marched out of camp in the morning, then back into camp at the end of each day.

Scipio made cunning use of his time before throwing the full weight of his army at Hasdrubal. The Romans and Carthaginians were in the middle of each line, where they fully expected to come to blows eventually. Their respective Spanish allies were deployed on the wings. Hasdrubal placed his elephants in front of his Spanish troops to buck up their courage.

Scipio had his soldiers breakfast before sunrise, and the cavalry was readied to move out at a moment’s notice. At daybreak Scipio hurled his horse troops and light infantry at the outlying Carthaginian defenses. These acted as a screen and also pressed the elephants into the center of the Carthaginian line. Scipio then had his Roman legionaries execute an intricate maneuver that brought them from the center of the battle line to the wings. He redeployed his Spanish troops to the center of his own line.

The Roman center was told to move forward slowly to delay contact with the Carthaginians as long as possible. Meanwhile, Scipio had his wings extend outward and move forward briskly to turn both flanks of the Carthaginian line. The internal flexibility of the Roman army made such a complicated maneuver possible. The experienced Roman legionaries overmatched the untrained Spaniards who had recently been brought into the Carthaginian army. Hunger and fatigue also hurt the Carthaginian cause. They had been taken off guard by Scipio’s move, and had not had time to eat. The lengthy period of standing under the Spanish sun sapped much of the Carthaginians’ remaining energy.

The Carthaginians attempted to withdraw, but the Romans, smelling blood once their enemy started to pull back, pressed all the harder. Despite Hasdrubal’s best efforts, the Carthaginian line began to crumble. A rout ensued, and the Romans snapped at the Carthaginians’ heels all the way back to their camp. The Romans would have stormed the camp as well, had not a thunderstorm struck at just that moment. For the time being, the Carthaginians were safe in camp, but for how long?

Rome’s Reversal of Fortune

Not waiting for an answer to that question, Hasdrubal left under cover of darkness the next night. He and his soldiers, pursued doggedly by the Romans, took refuge on a hill. Their position was utterly untenable, however, and Hasdrubal ungallantly left his surviving troops and made his own escape by ship to Cadiz, which was still in Carthaginian hands. Mago soon followed. The remnants of the once proud Carthaginian army in Spain were forced to hide as best they could in the inhospitable countryside.

Scipio’s dramatic victory over Hasdrubal Gisgo at Ilipa ensured that Spain was lost to Carthage forever. There were practically no Carthaginian troops left on the peninsula. Hasdrubal Gisgo and Mago soon left the country altogether. In the space of four years, Scipio had obtained a complete turnaround of Roman fortunes in Spain. He had avenged his father, his uncle, and all the other Romans who had fought and died in the Iberian theater over many years. Spain was his, and Rome owed its mighty son a great debt for his improbable success.

Join The Conversation

Comments