By Nicholas Varangis

Warfare History Network sat down with Terry Benedict, one of the Producers of the new Mel Gibson film Hacksaw Ridge to ask some questions about the film and its subject, Desmond Doss. The film details the actions of Doss, a conscientious objector who earned his Medal of Honor saving dozens of lives in the Battle of Okinawa. Terry Benedict has spend seventeen years on the project. He was writer, producer, and director of the companion documentary, The Conscientious Objector, which was released in 2004, and is one of few people alive today who knew Desmond Doss and his story intimately. In our interview with Terry Benedict, we ask him: Who was the real Desmond Doss, what makes his story so inspiring and unique, and what responsibilities does a filmmaker have when making a film like Hacksaw Ridge?

Warfare History Network: You’ve dedicated an impressive amount of time to detailing the life of Desmond Doss. How did you become interested in Desmond Doss’ story?

Terry Benedict: I grew up with parents who decided, in their infinite wisdom, that my sisters and I should not have a television until we hit about eleven to twelve years old. So we read voraciously. And like most boys, I was attracted to war stories and loved American history and world history as well. So at some point I went through the canon of the World War II books, like Guadalcanal Diary and 30 Seconds Over Tokyo and many others. And then I came across The Unlikeliest Hero which was the book about Desmond written by Booton Herndon, which was more of a YA, or young adult, book. I was really enamored with Desmond’s story because it was unlike any other story I had ever read, particularly with its focus on faith. Desmond and I also came from the same Christian denomination, the Seventh Day Adventists. That probably helped as well, because the Adventist world is a pretty small world, especially then.

When you’re growing up, things impact you. The seeds are planted and they just stick with you. Desmond’s story really did have an emotional impact on me. It helped set my moral compass to better understand how faith could work in reality. Even though it might not be terribly pleasant, there was always hope. And it also taught how we could serve our fellow man in difficult circumstances. So that was how I first came across it.

[text_ad]

WHN: What inspired you to retell Desmond’s story?

TB: It actually came back around to me well into my film career when I got a phone call telling me that, for decades, producers had been going after Desmond, that he didn’t want his story told, and asking what I thought about it. And I said, ‘well, before any movie gets made, there needs to be a documentary while Desmond’s still alive. His Medal of Honor citation reads like a big fish story that keeps growing and growing, and it just seems very unrealistic. So there needs to be some sort of documentary that’s done that corroborates the voracity of his story’. And that’s what we agreed to do.

But before that even happened, my relationship with Desmond was developing on a personal level. I went to some of the Medal of Honor reunions of the time, and Desmond was really reticent to having his story told by Hollywood. He did want to tell his story to youth, however, and he was very involved in youth programs in the church.

“Your story is so much bigger and has even more value…”

I kept coming back to him with this idea, saying to him ‘Your story is so much bigger and has even more value.’ And the themes of it, of serving your fellow man in the way that he did while standing up for your beliefs, driven by a deep conviction of your faith in God, would be a great encouragement to everyone. Especially when we get into difficult circumstances and just feel like there’s no hope, no light at the end of the tunnel.

What Desmond was mainly concerned about was the aspect of his character being compromised, with the glory going to him instead of to God. And so I was standing out in front of a grocery store talking about this and I told him ‘I’ll answer to God first, you second, and everyone will get in line, and I’ll do everything I can to get the essence of your character.’ He had a big grin on his face and he said ‘Ok, let’s do it.’ And that was how it started.

WHN: What kind of a person was the Desmond Doss who you knew?

TB: Well, Desmond was very much ‘What you see is what you get’. When you watch the documentary, you see the real Desmond. It’s a rare opportunity that we are making a movie where there’s a documentary, the quintessential documentary, that you can use as the library of reference to do the film.

For instance, for Andrew Garfield (who plays Desmond in the film), it provided him a lot of information about Desmond as a man, but also some of the mannerisms. I took Andrew into Virginia to show him where Desmond grew up and had him, in a very tactile way, touch and feel these places. I was also there as a reference library for him because I knew Desmond so intimately that he could ask me any questions he had. There was a lot that was not in the documentary, including some very intimate aspects of Desmond’s life that didn’t need to necessarily be shared publically, but would be pertinent to Andrew’s grasp of the layers of Desmond. If you watch both the documentary and the film, you see this seamless transition from the real Desmond to Andrew’s Desmond. It’s very uncanny.

WHN: What can we learn from Desmond’s character?

TB: I think there are a couple of key aspects of his character that we can learn from. One is that Desmond was very humble throughout his whole life and always willing to serve and go the extra mile for anybody. My Dad had a saying that he used to tell us kids when we were growing up: “What kind of world would it be if everyone behaved just like me?” Desmond personified that. When we think about ‘what kind of world would this be if we lived like Desmond? Would it be a better world?’ I think that would be true.

And I think that Desmond did this not just out of compassion, I think he had this unconditional love of humanity. It just leapt out of him. We talk about self-sacrifice. Desmond always was self-sacrificing his whole life. He was an extraordinary individual who personified Christ-like behavior. He wasn’t perfect, he didn’t claim to be perfect, and those of us who knew him knew he wasn’t perfect. But that wasn’t the point. The point was that he was driven and convicted by a philosophy and a theological understanding that he felt he was obligated to do in order to call himself a Christian.

“I Think that too many times in our history we try and evangelize our way of thinking on other people…”

One time I thought I was going to have this long and interesting discussion about ‘How do you justify not killing when the Old Testament is full of all kinds of killing?’ That conversation lasted no longer than 60 second. He said “Terry, God convicted me not to kill. If somebody else is convicted by God to kill, I pass no judgment on that person.” And that was the end of the discussion.

I think that too many times in our history we try and evangelize our way of thinking on other people instead of trying to understand our differences and looking at how we all collectively work together for the greater good.

Desmond proved that you can have a very different way of thinking in the military machine but be an incredible asset to that same military culture. And that’s what the military institution came to recognize. I saw that first hand. When we took Desmond to the Pentagon, there were four-star generals saluting him. He wasn’t even wearing his Medal of Honor, he was just in civilian clothes. As soon as he was introduced, they were saluting him and already knew who he was. He was a living legend in military culture. That’s when I realized that Desmond had an impact to the point that his reputation preceded him. Bring up his name in that culture and they knew exactly who he was. There’s a road named after him in the Butler base in Okinawa.

From what I see from the preview screenings of the film, with standing ovations, and from these kinds of Q&As, people are truly touched by his story. And I couldn’t be happier, because the documentary has reached out and touched a lot of people, and will be re-released and reach even more.

Desmond really wanted seeds to be planted of hope, and that hopefully people would turn to spiritual underpinning, and return to a more peaceful, restful life. That they would learn to truly love their brothers and sisters and find ways to serve their community.

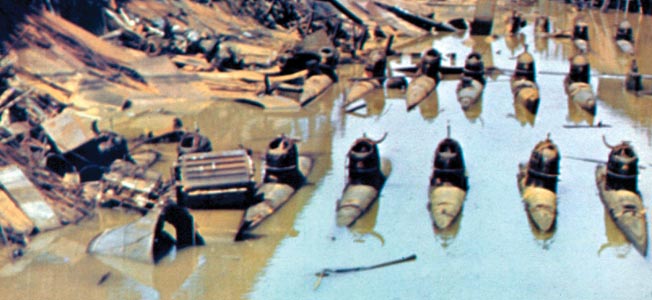

WHN: Capturing a time-period authentically is always a challenge in a period piece. What techniques did you use while filming to enhance the authenticity of the depiction of the life of Desmond Doss and the War in the Pacific?

TB: One thing Mel did was to have the whole cast and crew screen the documentary while in pre-production. When I got down to location, everybody was so appreciative of having the documentary as a frame of reference, because it gave them a taste of what life was like back then. I think that, between whole cast and crew, and the filmmaker himself, everyone was on the same page from the get-go.

That was very exciting to see that happen. Getting a movie made is a miracle in and of itself. Getting a great movie put together, that’s capturing lighting in a bottle. Mel did a terrific job doing that, while protecting the purity of Desmond’s story.

People talk about the graphicness of the film, but this is a unique story about a medic. Medics have a very graphic role to fill. It’s not pretty what their job is. When you have bullets and shells hitting bodies, that is not a pretty picture. So it shows the miraculous nature of Desmond’s heroics, and it has to be put in the proper context. And Mel did a great job in creating that context.

WHN: Just as Desmond Doss was an atypical war hero, the story in Hacksaw Ridge is atypical of a war movie. Whereas the average war hero, as depicted in cinema and as popularly thought of, earns his place through the lives he takes, Doss’s heroism is in how many lives he saves. With all the violence depicted in cinema, television, and video games these days, do you believe that filmmakers have a responsibility to present these sorts of counter-narratives of heroism through nonviolence?

TB: I think that our obligation as filmmakers is that we’re storytellers. And that we tell stories as authentically and as honestly and sincerely as we can. Personally, my preferred way is to tell the story as an open book and let the audience take away from it what they wish. For me, that’s what’s important. And I think that, in this instance, Desmond’s story was portrayed in a way that it is what it is, in an honest way.

I think people will take away from this film what they want to take away from it, and there’s going to be a discussion. I think some people will say this is an anti-war film, and others will say ‘no, it’s not’. Hopefully what we’ll see is an open and tolerant discussion, to listen to other people’s ideas and beliefs and react in a cooperative way that can work for that greater good.

That’s why Desmond called himself a conscientious cooperator. Because he never saw himself as somebody who would not cooperate.

“Desmond was somebody who was not in their camp, and they themselves had to go through their psychological inventory and reevaluate themselves.”

When I was doing research at the National Archives I came across a study that was done after WWII that was a survey of army infantrymen that found that, when infantrymen had the enemy in their gunsights, only 28% pulled the trigger.

What that said to me was that, even though people bore arms in what was considered a good war, that when it comes down to it, it’s still difficult to kill another human being, even in a war scenario. These discussions should be had because I think if we all understood what we believe in, in very definitive terms, that we would be better able to answer some of these questions and put together a better community.

What that said to me was that, even though people bore arms in what was considered a good war, that when it comes down to it, it’s still difficult to kill another human being, even in a war scenario. These discussions should be had because I think if we all understood what we believe in, in very definitive terms, that we would be better able to answer some of these questions and put together a better community.

That was one of the things I found out during the documentary process when I was interviewing some of the men who served with Desmond. I basically interrogated these guys for eight to ten hours a day when I would go visit them in their homes and record them.

And when they were sharing, not only did it have this cathartic effect for them to be able to get out what they had kept in for so long. And of course their families were very happy because they never knew what these guys had been through. You see in the documentary 92-year-old Jack Glover with tears coming down his face because of how much he loved Desmond. It allowed these guys to work through some very difficult times that they had been through when we talk about ‘well, Desmond didn’t carry a gun but these guys did’. These guys had to go through not just the war experience and the difficulties of the things they went through, they also had to deal with Desmond.

Desmond was somebody who was not in their camp, and they themselves had to go through their psychological inventory and reevaluate themselves. Who were these guys? Who were they really? As men?

That’s what Desmond’s story tends to do, if you watch the documentary or Hacksaw Ridge or both. And that’s the seed planting that really excites me in a way; to see people react and go through their own inventory to see who they are as a human being. Are they like Desmond? Or are they somewhere else on the spectrum? And again, would this world be a better place if I acted or behaved like this.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments