By O’Brien Browne

Smoke and ash drifted across the shattered ground. Dead faces peered up with lidless eyes from pools of stagnant water. Black flying objects screeched downward, bringing terror and death to the soldiers huddled below, while on the horizon the sky blazed red-orange with flame and the entire earth shook.

This is the fictional world described in J.R.R. Tolkien’s immensely popular trilogy, The Lord of the Rings, but it was based on the awful reality of the Western Front in World War I. Perhaps no other war has produced such an illustrious array of writers. Out of this fiery cataclysm, names such as English writers Robert Graves, Wilfred Owen, Rupert Brooke, and Siegfried Sassoon—to say nothing of such American writers as Ernest Hemingway, E.E. Cummings, and John Dos Passos, and German author Erich Maria Remarque—have been etched into public perceptions of World War I-inspired literature. Ironically, Tolkien, perhaps the most famous and widely read writer to emerge from the conflict, is almost never associated with it.

Yet World War I had a major creative impact on Tolkien, informing the universal themes that make his novels so vivid. Brooding evil arises out of the East, a grand alliance of forces forms in the West, and a war for the future of civilization takes place in a nightmarish lunar landscape filled with surging armies and killing machines—the very things Tolkien experienced firsthand in World War I. In particular, male friendship, fortified by the shared hardships of warfare, stands out in Tolkien’s writings, and it jars modern readers to read Tolkien’s foreword to the second edition of The Lord of the Rings. “By 1918,” he writes, “all but one of my close friends were dead.”

Tolkien’s Tea Club of the Barrovian Society

In 1889, Queen Victoria sat on the British throne, dourly surveying her mighty empire, which spread out from the British Isles to India, Egypt, Australia, Canada, and much of the rest of the planet. Britain’s powerful navy protected homeland and colony alike; her small professional army was battle hardened from fierce colonial wars. This was the world into which John Ronald Reuel Tolkien was born in Bloemfontein, South Africa, in 1892. Three years later, his mother brought him and his brother to England to escape the harsh African climate. Shortly afterward, the family was crushed to learn that Tolkien’s father had died of rheumatic fever. They moved to Sarehole, just outside the grim industrial city of Birmingham, where Tolkien’s mother gave him an excellent education at home. Her death in 1904 was another body blow to the young boy. The Tolkien children were raised by an aunt and a family friend.

At school, Tolkien’s linguistic gifts blossomed, and he excelled at Latin and ancient Greek, before devouring German, Gothic, Welsh, Finnish, and other languages. Tolkien was a member of his school’s cadet corps, riding with a territorial cavalry regiment in 1912. He made best friends with Christopher Wiseman, Geoffrey Bache Smith, and Robert Gilson, and together they founded the Tea Club of the Barrovian Society, or TCBS, named after their meeting place, the Barrow Store. It was an idealistic, irreverent, and pretentious little group. The witty aesthetic Gilson dreamed of becoming a renowned architect; Wiseman, sensitive and talented, wished to be a musician; literature-loving G.B. Smith longed to be a poet; and Tolkien, dreamy, ambitious, and hardworking, wrote tales of elves, dwarfs, and heroic supermen, inventing his own private languages for them.

Upon graduation, Tolkien was accepted into Oxford University, where he majored in Old English and Germanic languages while developing a relationship with Edith Bratt, his childhood sweetheart. Against the background of romance and ivy-covered university walls, Tolkien observed the slowly escalating tensions among the nations of Europe, which finally exploded into all-out war in 1914 after the assassination of the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

The TCBS Goes to War

Although many European men enthusiastically dashed to the colors of their respective nations to participate in a war that was to be over by Christmas, others greeted the conflict with indifference or repulsion. For his part, Tolkien decided to complete his studies and then join up, a primarily financial choice. Tolkien had always been desperately poor, and his only chance for survival after the war was to find a job in academia. After struggling so hard to better himself, Tolkien did not welcome the war, which symbolized for him “the collapse of all my world.” Still, after graduating with a first-class degree in 1915, he prepared to enlist in the British Army.

Tolkien’s friends in the TCBS had already reached the same conclusion. Gilson had joined in November 1915, going into the Cambridgeshire Battalion, later to be transferred to the 11th Battalion, Suffolk Regiment as a second lieutenant. Smith followed his friend a month later, the young poet being accepted into the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, although he would later be transferred to the 19th Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers, also as a second lieutenant. Like Tolkien, Wiseman opted to enlist later, going into the Royal Navy in summer 1915 to serve on the battleship HMS Superb. Although it was a hard decision for the young men, in reality there was little choice but to volunteer. “In those days,” Tolkien later recalled, “chaps joined up, or were scorned publicly. It was a nasty cleft to be in.”In 1915, the war was not going well for Great Britain and its allies. As Tolkien and his friends went through boot camp, the character of the war transformed, becoming more protracted and deadly than anybody had foreseen. The Lancashire Fusiliers, for instance, had taken part in a bloody but failed landing against well-entrenched Turkish forces at Gallipoli. On the Western Front, British forces had suffered appalling losses at Neuve Chapelle while Russians and Austrians battled it out in the Carpathian Mountains. On the home front, a German submarine campaign was strangling much needed food and weapon supplies. And in April 1915, a new horror appeared: along a four-mile stretch of the Ypres Salient in Belgium, the Germans struck combined French, Algerian, and Canadian divisions with a terrible new weapon—168 tons of chlorine, the world’s first poison gas attack. That autumn, Great Britain suffered 50,000 casualties in the Battle of Loos.

Tolkien Joins the Lancashire Fusiliers

At this bleak hour, Tolkien and the three other members of the TCBS gathered one last time to discuss literature and the future. On June 28, the 23-year-old Tolkien enlisted in the Lancashire Fusiliers, no doubt desiring to be close to G.B. Smith but also choosing the unit because it was full of Oxford men. This was typical of British Army recruiting at the time—young men joined up en masse by town, school, or trade, organized into regiments sporting such quaint names such as the Tyneside Commercials or the Manchester Pals; G.B. Smith’s battalion was known as the 3rd Salford Pals. The idea was that units made up of friends, relatives, and colleagues would be more cohesive and motivated on the battlefield. The tragic corollary to this thinking was that when the fighting was particularly intense, such close-knit groups would also fall en masse, wiping out entire school classes or neighborhoods in the space of a few bloody moments.

Because of his language expertise, Tolkien was trained in Yorkshire as a signals officer, responsible for battalion communications with headquarters. He learned map reading, Morse code, message sending via carrier pigeon, and field telephone operation. He memorized the art of station call signs—tactical voice communications with letters or digits representing companies, platoons, and sections—and also how to use signal flags and discs, flares, lamps, and heliographs as well as “runners,” soldiers who carried hand-written notes to headquarters under fire.

Like all new soldiers, Tolkien found boot camp dull, Army bureaucracy intolerable, and most of his commanding officers insipid. “War multiplies the stupidity by 3,” he wrote. But in training camp, a more subtle transformation was occurring within him. Great Britain’s first volunteer army had thrown together men from all walks of life and all social classes, and Tolkien developed “a deep sympathy and feeling for the ‘tommy,’ especially the plain soldier from the agricultural counties.” In socially stratified prewar England, Tolkien the Oxford man would normally never have had anything to do with such “commoners.”

On June 2, 1916, Tolkien received his embarkation orders. Now married to Edith Bratt, he visited her for the last time, harboring little hope that he would ever see her again. As he later remembered, “Junior officers were being killed off a dozen a minute. Parting from my wife then was like death.”

One by one, Tolkien and his friends went off to battle. While Wiseman experienced a comparatively “clean” war in the Navy, seeing sporadic action, Tolkien, Gilson, and Smith entered a war zone of gothic horrors for which nothing in their comfortably sheltered young lives had prepared them. Moving up into the front lines, they witnessed the genius of their enlightened epoch being used to kill masses of men. The earth of northern France was ripped up and broken, oozing mud from countless shell holes, the rotting bodies of dead men and horses littering the ground, grotesquely entwined with the hulks of rusting guns, smashed wagons, and barbed wire. The trenches were torn up by shell blasts, rat infested and mud filled, and adorned with hunks of putrid flesh and smashed equipment.

Tolkien disembarked on June 6, 1916, at Étaples, from where he and the 11th Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers, under the command of Lt. Col. Laurence Bird, were transported by train to the great British communication and supply center at Amiens and billeted near the front lines. The battalion was transferred to 74th Brigade, 25th Division for an upcoming offensive on the Somme River. Tolkien was assigned to A Company.

Tolkien in the ‘Big Push’

Neither he nor his men were aware of it, but they were about to participate in the greatest attack in the history of the British Army, the “Big Push” that Army planners had designed to break through the Germans lines in the rolling, chalky countryside near the Somme. After a massive artillery barrage, the Germans would be either dazed or dead, and the British Army would simply stroll over no-man’s-land, occupy the trenches, and roll up the rest of the enemy’s forces before breaking out into open ground. The war could be brought to a sudden and decisive close. That, at any rate, was the plan.

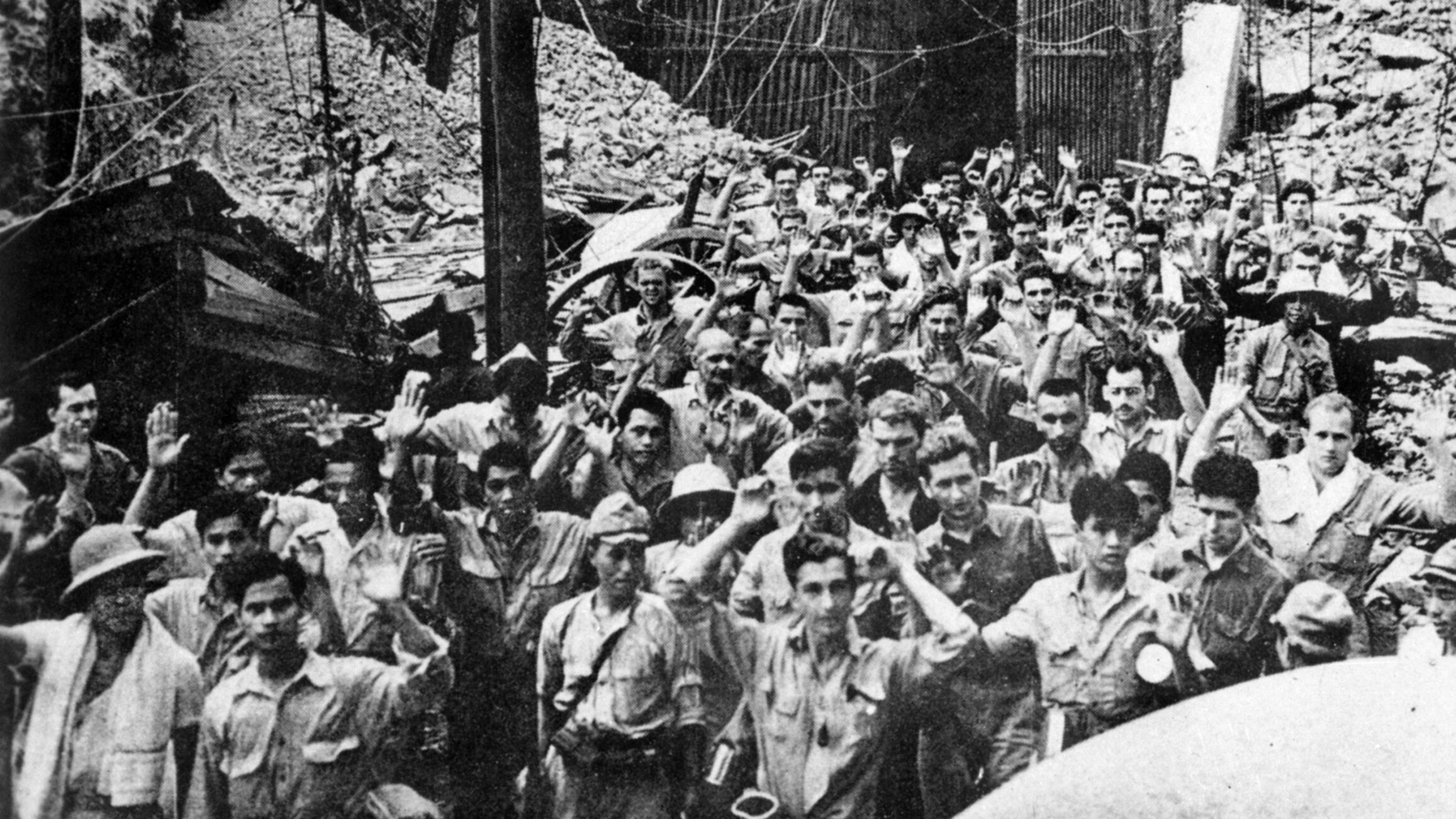

Because the vast majority of the men were green, Tolkien and his fellow officers were instructed to lead their troops into battle in parade fashion—long, even lines marching against the Germans in waves, their bayoneted rifles held “at the slope,” tilted slightly forward. For a week before the attack, 1,500 British guns had pulverized the German positions to soften them up and cut the dense wire entanglements through which the attacking British were to weave. Zero hour was set for 7:30 am, July 1, 1916. Some 200 battalions, containing 100,000 British troops, would go over the top. Gilson’s and Smith’s units were among those moved up to take part in the initial attack; Tolkien’s unit was held in reserve.

The morning of the attack was a poet’s morning of golden sunshine and wildflowers swaying gently in a faint breeze. It had rained the night before, and freshness was everywhere. Suddenly, at 7:28 am, a massive heap of dirt, German soldiers, and trees suddenly lifted into the air as British sappers blew mines under the German trenches, in one place scooping out a 90-foot-deep crater in the earth. This was followed by an eerie silence. Then, all along the line, the shrill sound of whistles trilled as British officers signaled their men to attack. The Army slowly surged up jumping-off ladders and began walking slowly toward the enemy lines.

Gilson had blown his whistle and led his men over the top. Their target was the enemy trenches near the village of La Boisselle. As Gilson and the 11th Suffolk advanced, they soon realized to their horror that the wire before them had not been cut by the artillery fire and that the Germans, well-protected in deep dugouts, had survived the massive bombardment. The Germans waited for the advancing British to come into range, then opened up with machine guns, small arms, and artillery fire. Before the leading wave had advanced 100 yards, men began dropping everywhere. A wounded company commander wrote: “My very last memory of the attack is the sight of Gilson in front of me and [another officer] on my right, both moving as if on parade, and both a minute or two later to be mortally hit.” The first of Tolkien’s friends had fallen. In a few moments, the 11th Suffolk had suffered 691 casualties. “My chief impression,” Tolkien wrote to Smith, reflecting on Gilson’s death, “is that something has gone crack.”

Smith, an intelligence officer in the 19th Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers, was also in action at the Somme. On July 4, he and his men attacked the Leipzig Salient, a strongly fortified section of the German line on Thiepval Ridge. Once again, the attack was repulsed with heavy losses. Smith survived, writing in a very nonpoetic manner in his battle report, “Owing to hostile MG [machine-gun] fire the advance was made by short rushes. Casualties were heavy.”

After Smith and his battered men were pulled out of the line for leave, he ran into Tolkien in the village of Bouzincourt, and the two old friends talked about their experiences.

Battle of Thiepval Ridge

Luckily for him, Tolkien had not taken part on the disastrous opening day of the battle, when a staggering 60,000 British soldiers fell, 20,000 of them killed outright. Held in reserve, his unit watched the lines of British wounded and German prisoners stream past. When elements of the 11th were thrown into the fighting, Tolkien was kept back to act as communications officer for the battalion. On July 14, he slogged through the battered remains of the village of La Boisselle, he and his men hauling signal flares, lamps, and rolls of telephone wire to maintain communication with headquarters. The 11th attacked German trenches around Ovillers and the fighting was fierce. Tolkien’s company commander was killed, just one of the 267 casualties the 11th suffered in two weeks of fighting. Tolkien was made battalion signal officer in command of several noncommissioned officers and privates.

Throughout July and August, the 11th was yanked in and out of the line several times. In late summer it was engaged in hard fighting at Thiepval Wood, especially a section of the German line known as the Schwaben Redoubt. Tolkien, with eight runners under his command, was assigned again to battalion headquarters. While the battle stormed about him, Tolkien had to ensure that vital battlefield information went out to his superiors while simultaneously coping with runners being wounded or killed and telephone lines being severed by hostile gunfire.

Tolkien kept up with his writing as well as he could under the circumstances. He recalled working on some of his stories “in grimy canteens, at lectures in cold fogs, in huts full of blasphemy and smut, or by candle light in bell-tents, even some down in dugouts under shell fire.” But such occasions were rare. “You might scribble something on the back of an envelope and shove it in your back pocket,” he later wrote, “but that’s all. You couldn’t write. You’d be crouching down among flies and filth.”

“It is You and I Now”

The war continued. In late October, Tolkien and his men were involved in bloody fighting to take Regina Trench, located a mere 200 yards from the British lines. Tolkien was stationed at battalion headquarters at Zollern Redoubt. The attack began at precisely 12:18 pm with an artillery barrage, before waves of British soldiers rushed toward the German trench. This time the artillery fire was effective enough to catch the Germans by surprise, and many were killed, wounded, or captured. One of Tolkien’s signalers was hit while carrying a pigeon basket; he joined 160 other men who were casualties, among them many officers knocked out while crossing no-man’s-land. For Tolkien and the 11th, this was the last fighting of the Battle of the Somme before they were pulled out of line for a much needed rest.

After surviving four hellish months in one of the war’s deadliest battles, Tolkien succumbed to the most humble but ubiquitous enemy of all—lice. With a fever of 103 degrees, he was sent back to Great Britain in early November, diagnosed with trench fever, a disease akin to typhus that was spread by infected lice. A vicious, debilitating, sometimes deadly disease, trench fever nevertheless was considered a “blighty wound,” a nonfatal wound that ensured that the victim would be sent back to Old Blighty—soldier slang for Britain—to recover. Such wounded men were congratulated by their envious comrades; hearing about Tolkien’s condition, G.B. Smith immediately wrote: “Stay a long time in England. I am beyond measure delighted.”

Tolkien spent the rest of the war in Harrogate Sanatorium and other Army facilities. In September 1918 he was deemed incapable of returning to active service. Back at the front, Tolkien was sorely missed. Although he often dismissed his war service with typical English self-deprecation, Tolkien was considered a good officer. On leave in 1917, Wiseman visited the convalescing Tolkien, telling his friend that he hoped Tolkien would not be sent back to the war. “It is you and I now,” Wiseman had written to him earlier. Throughout 1917 and 1918, Tolkien was struck by recurring bouts of trench fever and was in and out of the hospital. Whenever he was well enough, he continued to fulfill his duties, being promoted to full lieutenant. He also found time to write an unpublished elegiac piece on Gilson and Smith, and worked on his stories and languages

Meanwhile, his surviving friends were still at war. As Tolkien lay feverishly in bed, G.B. Smith and his men were settling down in the tiny village of Souastre, behind the front lines. Smith’s stay was uneventful until in late November 1916, when he was hit in the arm and buttock by shell fragments. At first, it was believed he received his own “blighty wound.” But by the first week of December, Smith was dead, killed by gangrene from the foul battlefield soil that infected his wounds.

The War Reflected in Tolkien’s Books

After the war’s end in 1918, Tolkien worked as an associate professor before he became a full professor of Anglo-Saxon languages at Oxford University. He continued to work on his novels, beginning with The Hobbit in 1937. Although he denied that World War I had any influence on his subsequent writing, warfare permeates Tolkien’s Middle-Earth just as it permeated Europe in the first half of the 20th century. No writer can divorce himself from the fires of his own experience—if he did, he would have nothing to write about. Contradicting himself later, Tolkien admitted that his stories had been “quickened to full life by war.”

Tolkien and his three friends are reflected in the four Hobbits—Frodo, Sam, Merry, and Pippin—in the wildly popular trilogy, The Lord of the Rings. The Hobbits’ long journey from the verdant fields of the Shire to the barren, evil land of Mordor neatly mirrors Tolkein and his friends’ journey from green England to the ruined stretches of northern France. Endlessly marching, they leave the West to battle a dark power in the East, much as real-life British soldiers did. The characteristics of Tolkien’s friends appear in the Hobbit’s personalities. The fun-loving G.B. Smith, for instance, serves as the model for Pippin. Sampson Gamgee, a well-known Edwardian doctor who invented Gamgee Tissue used in surgery, lent his name to Tolkien’s character Sam Gamgee, who himself was a composite of the men he had fought beside. “My Sam Gamgee,” Tolkien remembered, “is indeed a reflection of the English soldier, of the privates and batmen I knew in the 1914 war, and recognized as so far superior to myself.”

A vast array of Tolkien’s imagery could have been lifted directly from a World War I battlefield guide. There are the Dead Marshes, for example, “a place where the dead lay underneath a noxious film of stagnant water,” and the “Noman-lands” arid and lifeless, “choked with ash and crawling muds, sickly white and grey and pocked with great holes.” Hobbits Frodo and Sam take cover in craters much like shell holes, and a “foul sump of oily many-coloured ooze lay at its bottom.” Mordor’s fumes recall the Germans’ use of mustard gas, while the white and gray mud is similar to the deadly sucking muck of the Somme, where the chalky ground had been pulverized by artillery barrages. “The Dead Marshes,” Tolkien freely admitted, “and the approaches to the Morannon owe something to Northern France after the Battle of the Somme.”

Among the great attractions of Tolkien’s Middle-Earth are the realistic landscape descriptions and detailed maps he created for his imagined lands, reflecting the skills he had learned in map-reading and drawing courses at Army signalers school. Much of Tolkien’s world—the Hobbit holes, trolls’ caves, underground Dwarf and Elf kingdoms—mirrors the subterranean existence he experienced on the front lines in France, living in fetid trenches and deep dugouts.

Tolkien’s love of huge and heroic battles, such as the fall of Gondolin in The Silmarillion, the Battle of the Five Armies in The Hobbit, or the great war epic in The Lord of the Rings, have their origins in the real-life Battle of the Somme. Tolkien always denied, however, that the Orcs, a cruel race, represented German soldiers. He wrote to his son in 1941: “I have spent most of my life studying Germanic matters (in the general sense that includes England and Scandinavia). There is a great deal more force (and truth) than ignorant people imagine in the ‘Germanic’ ideal.”

Tolkien’s details reveal his military training: the skill with which Sam makes a smokeless fire; how the men of Gondor, like army engineers, build bridges and defensive works; and the Hobbits’ backpacks, much like a soldier’s kit of rolled blankets, cooking pans, spoon and fork, tinderbox, and a small store of salt, show an accuracy that any soldier would appreciate. And just as Tolkien’s trench fever recurred in debilitating waves, so too does Frodo suffer from painful fits long after the wars of Middle-Earth have drawn to a close, leaving him lying prone on his bed. “I am wounded,” he tells Sam, “wounded; it will never really heal”—a sentiment many physically or emotionally scarred soldiers from any war can share. Significantly, the destruction of the Dark Lord’s empire in The Return of the King is powerfully reflected in reality as World War I swept away several great kingdoms—Czarist Russia, the Ottoman Empire, Imperial Germany, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The impact of the war on Tolkien’s works was obvious to those who knew him best. Tolkien’s close friend and fellow Oxford scholar, C.S. Lewis, author of the Chronicles of Narnia books and a veteran himself, recognized the war in Tolkien’s writing. The conflict that dominates The Lord of the Rings, Lewis pointed out, “has the very quality of the war my generation knew. It is all here: the endless, unintelligible movement, the sinister quiet of the front … the lively, vivid friendships.” Finally, in 1944, Tolkien admitted the effect of the war on himself, writing to his son Christopher, then serving in the Royal Air Force, “I hope that in after days the experience of men and things, if painful, will prove useful. It did to me.”

The Cost of Creativity

Paul Fussell’s influential The Great War and Modern Memory argues that the romantic epic suffered a fatal wound in the “stupid” and “senseless” First World War. Tolkien would have disagreed. In stark contrast to the disillusionment and antiwar sentiment of the postwar period, Tolkien unabashedly kept alive the tradition of war as a noble and romantic ideal. He not only rejected modernism, but revived the heroic epic in English literature. The romantic epic lives on with vigor and dash in Tolkien’s cavalry charges, his beautiful princesses, and shimmering enchanted forests. Since his death in 1973, millions of Tolkien’s books have continued to sell around the world, and he is easily the most unique, influential, and widely read writer to emerge from the inferno of World War I. A three-movie trilogy of his works directed by Peter Jackson concluded by sweeping the Academy Awards in 2004.

But such creativity had its costs. Like many former soldiers, Tolkien downplayed, suppressed, and even denied the effects of the war on him, yet they stayed with him all his life. In 1940, writing to his son Michael who had volunteered to fight in World War II, Tolkien hinted at the things he had lost in the First World War. “I was pitched into it all, just when I was full of stuff to write, and of things to learn,” he said, “and never picked it all up again.” He and Christopher Wiseman—the only survivors from the TCBS—remained lifelong friends, meeting whenever they could to remember their friends in better times.

Tolkien experienced pain all his life—the early deaths of his parents, financial hardship, the war. Like many people, he retreated into his mind, and there he found an enchanted land of heroes, beauty, and great deeds. Still, the memories remained. “I can see clearly now in my mind’s eye,” Tolkien recalled, “the old trenches and the squalid houses and the long roads of Artois, and I would visit them again if I could.” He never did, except in his books.

The war changed Tolkien, as it changed everyone. It injected loss and sadness into his writing, and made his descriptions more poignant because they were more real. Mordor could not have existed had Tolkien not experienced it firsthand on the Somme. But the war also taught him to value positive things as well—pity, beauty, heroism, loyalty, and the meaning of friendship—themes that run throughout all of his works and still reflect the lives and aspirations of millions of readers today.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments