By Roy Morris jr.

Charles Stuart liked to gamble. The 21-year-old son of slain English King Charles I was a fixture at the gaming tables and boudoirs of Europe, where he had spent the last half decade in restless exile while his father unsuccessfully sought to hold onto both his crown and his head. Following his father’s execution at Whitehall, London, on January 30, 1649, the young prince had returned to his ancestral home in Scotland, rallying the disaffected Scots to rise against the English Puritans (or Parliamentarians) led by Oliver Cromwell, who had decisively defeated them at the Battle of Dunbar on September 3, 1650.

Crowned king of England and Scotland (then separate countries) on January 1, 1651, Charles II had found little time to pursue his pleasures. With the grudging assistance of Scottish General David Leslie, Cromwell’s bested opponent at Dunbar, the new king had spent the past six months rebuilding his Royalist forces and making plans to recapture the throne and avenge his father. He had cobbled together an army of about 15,000 men, most of them Scots who hoped to forcibly impose their Presbyterian religion on Anglican England. Charles was more or less indifferent to the religious underpinnings of the war—if anything, he tended to favor his Catholic mother’s church—but he had willingly signed a “Solemn League and Covenant” agreeing to promote Presbyterianism as the new state religion once a Stuart sat again on the English throne.

Plotting a Royalist Invasion: Scotland or England?

Charles and Leslie differed greatly on the best way to effect such a restoration. Having seen at Dunbar what a Cromwell-led Puritan army was capable of achieving, Leslie wanted to keep the fighting close to home in Scotland, where Royalist sentiments remained strongest. The king disagreed. Despite retaining something of his father’s Scottish accent, Charles did not feel at home in chilly Scotland. He wanted to head south immediately and march directly on London, while Cromwell was still occupied with besieging the Scottish stronghold at Perth. In the king’s vision, thousands of monarchy-loving Englishmen would flock to his banner, united in their love of his father and the Presbyterian Church—more or less in that order. Leslie had his doubts. With a well-honed sense of Scottish fatalism, he urged the king to stay where he was, at least until more troops could be raised from the northern highlands.

Events soon forced their hands. On June 27, a Parliamentarian force led by Lt. Gen. John Lambert defeated a Scottish force at Inverkeithing on the Fife peninsula, cutting the kingdom in two and making the capture of Perth inevitable. The Royalists had three options, none of them good: they could melt into the highlands and fight a rear-guard guerrilla war; they could challenge Cromwell to another do-or-die battle inside Scotland; or they could invade England and hope to beat the Puritans back to London. Ever the gambler, Charles chose the third, and riskiest, option. Scottish Duke William Hamilton summed up the prospects gloomily: “Since the enemy shuns fighting with us, except upon advantage, we must either starve, disband, or go with a handful of men into England. This last seems to the least ill, yet it appears very desperate to me.”

Hamilton knew what he was talking about. His father, James, the first Duke of Hamilton, had led another invasion force into England three years earlier. At Preston, on the west coast of England, the Scots had been caught and annihilated by the quick-marching Cromwell on August 17, 1648. The first duke had been captured and executed for his trouble. His son did not relish a second family encounter with Cromwell and his battle-hardened New Model Army.

But Charles felt, perhaps rightly, that he had no choice. The Puritans’ ironclad naval blockade prevented either reinforcements or supplies from reaching Scotland. And the Scots themselves, who had sided against his father in the first round of the civil war, were a troublesome ally at best, given alternately to defeatist sulking or sudden headlong suicidal charges. Charles would rather risk appealing to his father’s former English supporters than the dour and unpredictable highlanders from the north. On July 31 the king led his new army south from Stirling, crossing the border into England 12 days later. For speed of movement, most of his men were mounted, and at first they made good progress despite the fact that several hundred men deserted along the way.

“That Mongrel Scots Army”

Still, it was long odds—and about to become even longer. Cromwell, ever vigilant, had not been taken by surprise. The capture of a Royalist messenger earlier that spring had given Cromwell access to the king’s secret code and the names of many of his English supporters. Although still lingering around Perth waiting for the town to surrender, Cromwell had taken pains to prepare for an enemy thrust to the south. He alerted Parliament to the threat, urging them to call out the free-standing militias and dispatching two separate cavalry forces under the young but skillful Lambert and Maj. Gen. Thomas Harrison to shadow the upstart king every step of the way. Meanwhile, some 2,000 suspected Royalist supporters were rounded up and arms caches were removed from the great houses and kept under Puritan guard at central locations. Informers, promised a third of their victims’ estates, disclosed anyone suspected of favoring the king, and many Royalists decided understandably that they would sit out the coming invasion and, in essence, mind their own business.

But by allowing Charles free entry into England, Cromwell too was taking a risk. Despite heading what one Puritan newsletter described as “that mongrel Scots army,” the new king—whether or not he was recognized as such by Parliament—was an attractive, even gallant figure. No one could say with complete confidence how few, or how many, common Englishmen might rally to his side. One solid Royalist victory on English soil might well trigger a popular uprising. Nevertheless, the coldly pragmatic Cromwell felt that he had little choice but to toss the dice. As he informed Parliament: “We have done to the best of our judgments, knowing that if some issue were not put to this business, it would occasion another winter’s war, to the ruin of your soldiery.” Like Charles, he did not wish to spend another rain-soaked winter in Scotland.

First Confrontation with the Invasion Force

Leaving Lt. Gen. George Monck behind in Scotland to command a standing force of 6,000 of his worst soldiers, Cromwell hurried south with the bulk of his army—nine infantry regiments, cavalry and artillery. Marching 20 miles a day in some of the hottest summer weather in memory, Cromwell’s Puritans reached the River Tyne in seven days, entering the border town of Ferrybridge on August 19. The soldiers, all veteran campaigners, were allowed to strip off their coats and armor and march in their shirtsleeves; townsfolk were conscripted to carry the men’s arms and equipment for them. Meanwhile, Cromwell instructed Lambert, his able young cavalry commander, to continue following Charles’s army. “Attend the motions of the enemy, and endeavor the keeping of them together, and also impede his march,” Cromwell ordered. Thanks to Lambert’s proven efficiency, Cromwell soon knew every step the Royalists took.

The Puritan leader was surprised and gratified by events on the ground. It was to the Parliamentary banner, not the king’s, that the common folk of England flocked, seeing the campaign as an outright invasion of their country by Scottish brigands who, it was said, “had given up their own country for lost, which they had not the courage to defend.” Across northern and central England county militias rallied, moving into position to guard against Royalist insurrections and, if necessary, to defend the capital city of London itself. Cromwell had always scorned the militias, preferring to depend on his veteran regulars, but the sheer numbers of new volunteers helped demoralize Charles and his Scottish allies and literally gave them pause.

At Warrington, 16 miles east of Liverpool on the River Mersey in Lancashire, Charles’s army confronted a mixed group of Cheshire and Staffordshire militia augmented by Lambert’s regular cavalry. On August 16, the Royalists attacked and forced back the Puritan forces from the bridge. The marshy ground was unsuited for Lambert’s horsemen, and he was under orders not to bring on a general engagement. The cavalry withdrew, much to the delight and derision of the Scots, who flourished their weapons at the riverside and shouted at the retreating Puritans: “Oh, you rogues, we will be with you before your Cromwell!” That remained to be seen.

“We Must Either Stoutly Fight or Die”

Despite the nearly bloodless victory at Warrington, Charles’s principal advisers were still worried. Leslie, as always, was the most concerned. Although the erstwhile Parliamentary governor of Gloucester, Sir Edward Massey, had joined the king’s banner, there was little evidence of large-scale defections to the Royalist cause. A visitor to Charles’s camp recounted that the king had jokingly chided Leslie: “How could he be sad, when he was in the head of so brave an army and demanded of him how he liked them.” Leslie answered “that he was melancholy indeed, for he well knew that the army, how well soever it looked, would not fight.” Said another equally dispirited Royalist: “I confess I cannot tell you whether our hopes or fears are greatest, but we have one stout argument—despair; for we must either stoutly fight or die.”

Faced with such sentiments, Charles at length was persuaded to give up his dream of marching directly on London and instead move west into the more favorable Royalist territory near the Welsh border. There, he could rest his army and recruit more men from the famously hard-fighting Welshmen. (He would also have an open line of retreat to the coast, if it came to that.) Reluctantly, Charles wheeled his army west and headed for the crossroads town of Worcester, athwart the Severn River that formed the eastern border of Wales. The weary Royalists arrived at the outskirts of the city on August 22 and immediately set to work strengthening the town’s defenses. All local males between the ages of 16 and 60 were ordered to assemble in a field outside Worcester and listen to an impassioned speech by the king, who promised general pardons and good pay to anyone who would join his ranks. A few hundred new recruits straggled in, but nowhere near the numbers that Charles would need to fight Cromwell and his army, which scouts reported lurking nearby. The king’s gamble had left him holding a very weak hand. He knew it. “For me,” he mordantly told a confidante, “it is a crown or a coffin.”

Cromwell’s Risky Gambit

Two days later, on August 24, Cromwell reached Warwick, 40 miles east of Worcester, uniting his regulars with a mass of volunteers—27,000 men in all. For the first time in his career, Cromwell would have a better than two to one advantage over his opponents. Given his past history of success with much smaller odds, it was clear that Cromwell was holding a much larger stack of chips. Characteristically, he was about to go all in.

Charles did what he could to lessen the odds, sending Massey and 300 men to safeguard the nearest crossing point of the Severn, nine miles south of Worcester at Upton. The king directed Massey to destroy the lone bridge across the river, but for some inexplicable reason Massey delayed. Meanwhile, the ever-vigilant Lambert arrived on the scene, noted that the bridge was neither destroyed nor guarded, and sent a company of dragoons clattering across the span to seize the high ground at Upton Church. The now-alerted defenders counterattacked, but Lambert poured more men into town and eventually the Royalists were forced to retreat, carrying the badly wounded Massey with them. Cromwell now had a beachhead on both banks of the Severn, and he quickly augmented Lambert’s force with a column of regulars and militiamen led by Lt. Gen. Charles Fleetwood. Soon, there were 14,000 Parliamentary troops on the western side of the river, forcing Charles to divide his already badly outnumbered garrison. The noose was tightening around the king’s neck; he might well have thought of his father’s neck, stretched out before the executioner’s axe at Whitehall 21/2 years earlier. Many of his leading officers, one townsman observed, “appeared utterly dispirited and confounded” by the swiftly unfolding events.

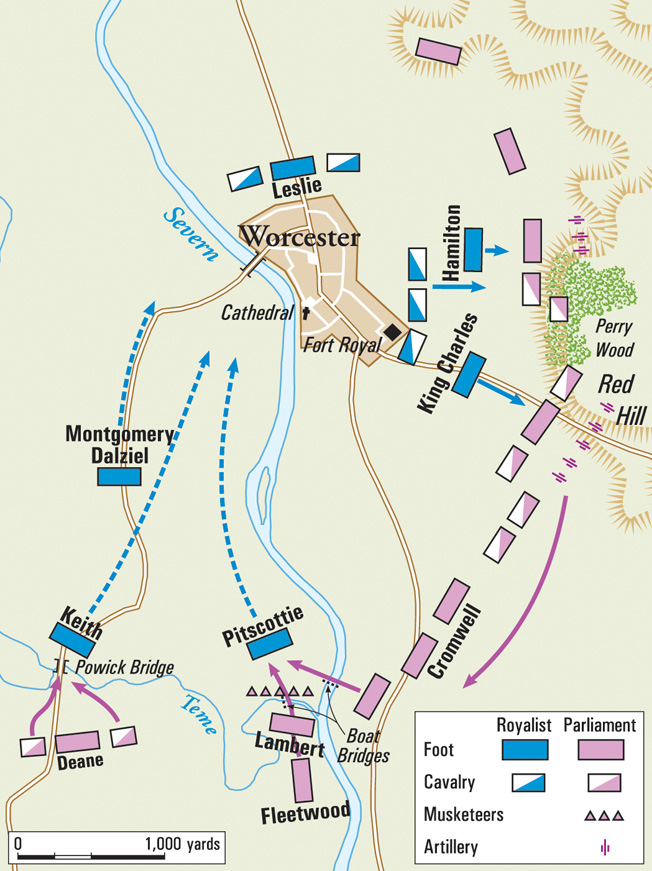

Cromwell, never less than supremely confident himself, moved deliberately, concentrating the other half of his army on two hills, Red Hill and Perry Wood, just east of Worcester. He set his heavy artillery between the two high points but delayed firing to give his men time to construct a pontoon bridge across the Severn at its conjunction with the smaller, shallower River Teme. Fleetwood would lead the crossing there, while Colonel Richard Deane directed a second force to attack Powick Bridge, a couple of miles due west of the Severn. Cromwell did not intend to attack Worcester head-on, but rather to trap Royalists in a steadily tightening vise until the king was forced to abandon his defensive position and attack Cromwell in the open ground east of town. It was the same plan he had used to good effect at Dunbar one year earlier.

By sheer coincidence—although some claimed later that Cromwell had purposely chosen the time—the battle opened on September 3, exactly one year to the day after the Puritans’ great victory at Dunbar. General Leslie, who had lost the battle that day, was unlikely to have missed the ominous anniversary.

By dividing his own forces, Cromwell was taking a large risk. If the Royalists could somehow stop Fleetwood and Dean from crossing the rivers, Charles might suddenly attack Cromwell’s position east of Worcester and overwhelm the Puritans before they could reunite their forces. That would depend on the comparatively inexperienced Charles, still only 21, taking the initiative against one of the world’s greatest battlefield commanders. It was another gamble that Cromwell, the abstemious Puritan, was happy to make.

The Battle Shifts Toward Worcester

Sometime before 6 am, the Puritans began their attack. Fleetwood’s 5,000-man force, moving up the west bank of the Severn, slowed its advance to cover the progress of the 20-boat caravan heading for the pontoon site to the east. Charles, watching developments through a telescope from the tower of Worcester Cathedral, dispatched two brigades, under General Robert Montgomerie, to hold the line at the Teme. Colonel Sir William Keith’s brigade was sent to contest Powick Bridge, the site of Royalist Prince Rupert’s long-ago triumph over the Parliamentarians in 1642, while Maj. Gen. Colin Pitscottie’s Scottish Highlanders were ordered to contest the pontoon-bridging efforts at the confluence of the two rivers. The bulk of the cavalry, under Leslie, congregated north of Worcester where, true to form, the fretful general kept his forces out of the fight, intending them to be “a body to fall on and assist where need should arise.” In other words, Leslie was already planning to cover a retreat.

For a time, it did not appear that he would be needed in such a role. Rallied by a quick visit from Charles to their position on the Teme, the Scottish defenders held fast, beating back several attempts by the Puritans to cross the stream at Powick Bridge. Fleetwood’s efforts to throw across a pontoon span farther east were also meeting with little success. Cromwell, seeing the lack of progress, sent a small body of troops across the Severn by boat to safeguard the contested triangle between the rivers’ junction. He directed the men to throw up pontoon bridges “a pistol shot”—50 yards—apart from each other in preparation for an influx of reinforcements. In a remarkable feat of battlefield construction under fire, the Puritans managed to erect the pontoons, and between 3 and 4 pm Cromwell personally led a handpicked force of men, including his own bodyguard and the veteran infantry regiments of Colonels Francis Hacker, Richard Ingoldsby, and Charles Fairfax, across the river. The Highlanders, poorly led by Pitscottie, were too far away to contest the beachhead, and additional Puritan cavalry swept the defenders’ flanks on the open ground west of the Severn.

With the pressure to his front partially relieved, Fleetwood managed at last to throw his own pontoon bridge across the Teme and threaten the Scottish flank at Powick Bridge. Colonel Keith led his men in a strategic withdrawal toward Worcester, contesting each tree, bush and hedgerow between the bridge and the town. “The dispute was long and very near at hand,” wrote one Puritan observer, “and often at push of pike, and from one defense to another.” At last, running out of ammunition, the Scots broke, some racing for refuge in Worcester, others continuing north into the open countryside beyond in the hope of escaping the Puritan trap. In the growing confusion, Keith was wounded and Montgomerie was captured.

Fighting in the Streets

Charles, back in the cathedral tower inside Worcester, decided on one last gamble: he would lead his men out of the city, as Cromwell had hoped, and attack the enemy east of the Severn at Red Hill. With more and more of Cromwell’s men drawn into the triangle west of the river, the king reasoned that a sudden determined charge might break through the Puritan stranglehold. He was very nearly right. Aided by the fact that the troops left behind on the hill were mainly untried militia, the Royalists overran the musketeer pickets behind a stand of hedgerows, drove off a troop of Puritan cavalry, and seized Cromwell’s artillery.

For a brief moment the entire battle hung in the balance. Charles’s courageous charge, assisted by the Duke of Hamilton, was on the verge of achieving a stunning 11th-hour triumph. But the redoubtable Puritan cavalry commander John Lambert, who earlier had refused orders to reinforce Fleetwood on the west bank of the Severn, stood firm. “If the enemy should alter their course, and fall upon them on this side, they might probably cut off all that remained,” he had reasoned. Now, with his horse shot from under him, Lambert took charge of the green militia, which resolutely held firm until the ever-alert Cromwell could rush reinforcements back across the river. The Royalist tide had crashed and foundered against the adamantine wall of Puritan resistance.

It was now about 5 pm, and the battle, to all intents and purposes, was over, although a good deal of last-ditch fighting—and dying—remained. One of the dead was the Duke of Hamilton, whose father had been an earlier victim of Cromwell. Many Scots took refuge in the earthworks at Fort Royal, a small redoubt overlooking Sidbury Gate, refusing a personal plea from Charles to come out and make a stand. (Later, the fort’s defenders would also refuse a demand by Cromwell that they surrender, and some 1,500 Scots, defiant to the last, would be overrun and cut down to the last man by the exultant Puritans.)

Increasingly frantic but not panic-stricken, the young king raced through Worcester attempting to organize another charge. Leslie, as usual, was no help, “riding up and down as one amazed or seeking to fly,” in the words of a disgusted fellow Royalist. It is doubtful that Leslie was actually amazed by the battle’s outcome—he had been predicting as much for several weeks. As the fighting spread through the streets of the town itself, Charles made one last attempt to rally his forces at Sidbury Gate. It was too late. “I had rather you would shoot me than let me live to see the consequences of this fatal day!” he shouted in frustration. Instead, a force of Royalist cavalry led by the Earl of Cleveland clattered down High Street, buying time for the monarch to escape through the northernmost St. Martin’s Gate.

“The Faithful City”

In many ways, the king’s greatest adventures were still to come, but for the bulk of his army the battle—and indeed the war—were over. Overrun on three sides, some 2,000 Royalist defenders at Worcester were killed; a staggering 6,000 to 10,000 others were captured, including all the surviving Scottish commanders. The English captives were conscripted into the New Model Army and sent to Ireland for further service; the Scots, less fortunate, were deported to New England, Bermuda, and the West Indies to work as indentured servants on English plantations. Very few of the Scots who had invaded England two months earlier ever saw their craggy homeland again.

The gutters of Worcester, “the faithful city,” literally ran with blood, and a survivor recalled later that “what with the dead bodies of the men and dead horses of the enemy filling the streets, there was such a nastiness that a man could scarcely abide the town.” At nearby Kidderminster, Puritan minister Richard Baxter was roused from his bed by a troop of Royalist cavalry fleeing pell-mell through the town. “Till midnight the bullets flying towards my door and windows, and the sorrowful fugitives hastening for their lives, did tell me the calamitousness of war,” he remembered. Some of the fugitives were so exhausted that they fell asleep in the fields outside Worcester, where a number of them were robbed and cudgeled to death by looters.

“As Stiff a Contest as Ever I Have Seen”

By nightfall the fighting had died away. Cromwell, never one for mincing words, called the battle “as stiff a contest as ever I have seen.” Retiring to the aptly named King’s Head Inn at Aylesbury, he announced the stunning victory to Parliament, sending a famous letter to William Lenthall, Speaker of the House of Commons. “The dimensions of this mercy are above my thoughts,” Cromwell wrote. “It is, for aught I know, a crowning mercy.” He added a gracious and uncharacteristic postscript. Although formerly contemptuous of militia forces, he recognized the importance of their stand at Red Hill. “Your new raised forces,” he advised Parliament, “did perform singular good service, for which they deserve a very high estimation and acknowledgement.” In faraway New England, Puritan minister Hugh Peters also acknowledged the humble militia. “When their wives and children should ask them where they had been and what news,” preached Peters, “they should say they had been at Worcester, where England’s sorrows began, and where they were happily ended.”

The unlikeliest tribute came 135 years later, when American patriots John Adams and Thomas Jefferson toured the battlefield at Worcester. Peering over the earthworks at Fort Royal Hill, Adams admitted to being deeply moved by the sights, although he was sufficiently irritated by local residents’ lack of knowledge about the battle to give them an impromptu lecture on English history. “The people in the neighborhood appeared so ignorant and careless at Worcester that I was provoked and asked, ‘And do Englishmen so soon forget the ground where liberty was fought for? Tell your neighbors and your children that this is holy ground, much holier than that on which your churches stand. All England should go in pilgrimage to this hill, once a year.’”

Having helped his own country throw off the yoke of monarchy, Adams knew how hard it was to knock the crown off a king’s head. It was a lesson the English would surprisingly relearn within a decade of the signal Puritan victory at Worcester.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments