By William Welsh

Five hundred Spanish musketeers filed into the dim forest on the southern edge of a wooded plain south of the border fort at Rocroi, France, at dusk on May 18, 1643. Their commander, Lt. Gen. Baltasar de Mercader, had orders to ambush the cavalry on the French army’s right wing by firing into its flank when it advanced into battle the next morning. Sentries were posted, but Mercader allowed the majority of his force to rest through the night so that they would be fresh for the main battle.

While the musketeers were making themselves comfortable, a deserter from the Spanish army informed the French of the location and intent of the ambush party. To counter the threat, 22-year-old Duke Louis d’Enghien, commander in chief of the army sent to relieve the French garrison trapped inside the fort by the Spanish, ordered nearly 1,500 French musketeers to wipe out the ambushers in the dark of night.

At 3 am, the French infantry charged into the woods. The surprise was complete. The French foot soldiers shot, clubbed, and stabbed the Spanish where they slept. A few, including Mercader, were led away as prisoners. The victory in the night skirmish on the eve of the main battle not only deprived the Spanish of one of their best infantry commanders, but also eliminated a block of firepower that the Spanish would badly need once the battle was under way. It was the first in a string of misfortunes that would befall the Spanish army at Rocroi.

Clash Between France and the Hapsburg Monarchy

The French and Spanish had been at each other’s throats for nearly three centuries leading up to the high-stakes battle at Rocroi. By the early seventeenth century, the king of Spain headed the Hapsburg dynasty and controlled most of Italy, the upper Rhine, and the Spanish Netherlands, a geopolitical situation that enabled Spain to contain France and block it from expanding on land. In the murderous war between Catholics and Protestants that would engulf central Europe in the second decade of the new century, it mattered little that both France and Spain were Catholic nations. Their monarchical rivalry trumped any shared sense of religion.

The Spanish had been trying to suppress the rebellious northern provinces in the Spanish Netherlands for nearly a half century by the time the Thirty Years’ War began. After four decades of fighting, the Protestant provinces of the Netherlands entered a treaty with Spain in 1609, the terms of which granted them independence and also imposed a 12-year armistice. When war in the Netherlands resumed with Spanish attacks on Dutch forts in 1622, France found itself having to choose sides in two overlapping conflicts while it sought to roll back the growing Hapsburg power.

For the first half of the Thirty Years’ War, France was content to fight a proxy war against Spain by helping fund the armies of Protestant combatants Sweden and the United Provinces in their fight against the Hapsburg-controlled Holy Roman Empire’s Imperial Army and the Spanish Army of Flanders. Under the rule of King Louis XIII and his chief adviser, Cardinal Richelieu, the French succeeded admirably during that time in keeping their country free from the ravages of warfare. The downside was that when they eventually decided to commit their military forces, the French lacked both experienced troops and commanders.

The threat to France grew more immediate when King Philip IV of Spain’s brother, the Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand, was appointed to serve as the governor of the Spanish Netherlands. Marching across the Alps in summer 1634 with 20,000 Spanish soldiers, he joined forces with a Hapsburg Imperial Army led by his cousin, Archduke Ferdinand, and crushed Swedish-led Protestant forces in early September at Nordlingen in Bavaria. Two months later, he arrived in Brussels. To prop up Protestant forces on the left bank of the Rhine, the French agreed to provide 12,000 troops. The introduction of these troops marked the beginning of open conflict between Bourbon France and the Hapsburg dominions.

Francisco de Melo Leads the Army of Flanders

In May 1635, France declared war on Spain on the grounds that Spanish forces had entered the city of Trier, which was under the protection of France. The following year, the French invaded the Spanish Netherlands, hoping to join forces with the Dutch. But the Dutch were reluctant to openly ally themselves with the French, and the campaign drew to a close without achieving its lofty objective of partitioning the Spanish Netherlands. The following year the tables were turned, and the Cardinal-Infante invaded France at the head of 32,000 Spanish and Imperial troops. With little to stop him, the Cardinal-Infante captured the fortress of Corbie on August 14 after a week-long siege. Although the Spanish were within a few days’ march of Paris, the departure of Imperial forces to meet threats at the opposite end of the empire compelled the Cardinal-Infante to withdraw his army to its base in the Spanish Netherlands.

In the latter part of the 1630s, the Cardinal-Infante’s Army of Flanders became less of a threat to the French as it became increasingly bogged down against Dutch forces. At the same time, political turmoil in Spain sapped the army’s funding and manpower, and members of the royal court blamed the Cardinal-Infante for the loss of the upper Rhine to French and German Protestant forces. By the close of 1638, the French had occupied most of Alsace and Lorraine, which lay within the Holy Roman Empire. Two years later, Spain was rocked by revolts in Catalonia and Portugal, which consumed the attention of Philip and his chief minister, the Count of Olivares, leaving the Cardinal-Infante without the political and financial support he needed to effectively fight the French and Dutch. Through a great effort on his part, he managed to keep the Dutch in check during 1640-1641. But the superhuman effort involved in managing the political and military affairs simultaneously of the Spanish Netherlands destroyed Ferdinand’s health, and on November 9, 1641, he died at the early age of 31.

To succeed the Cardinal-Infante, Philip chose the 46-year-old Portuguese diplomat and general, Francisco de Melo, the Marquis of Tordelaguna. Hoping to gain the support of the Cardinal-Infante’s retinue in Brussels, Melo distributed appointments in the Army of Flanders to as many of Ferdinand’s advisers as possible. The upshot was that many experienced generals and colonels were displaced from positions they had earned through merit. It was a short-sighted decision, and one that would have a devastating impact when the Army of Flanders met a well-led French army of equal size on the battlefield.

Melo took the field the following spring. After recapturing the fortress of Lens, which lay inside the Spanish Netherlands on the French frontier, he intercepted a French force half his size at Honnecourt on the Escaut River. The Spanish delivered a sledgehammer attack on May 26, forcing the French to abandon the field. Of the 10,000 French engaged, more than 6,000 were killed, wounded, or captured. Despite the decisive victory, Melo opted not to invade France. For such an operation, he would have had to rely heavily on his cavalry, and he was acutely aware that his Walloon cavalry was no match for the French horsemen in either numbers or training.

The Deaths of Cardinal Richelieu and King Louis XIII

Cardinal Richelieu had kept the top French commanders on a tight rein during the seven years that France had been fighting against Spain before the debacle at Honnecourt. The cardinal had been reluctant to allow anyone other than himself or the king to direct a large operation. Because of this, France’s top generals held no independent commands in those years. That changed with Richelieu’s death on December 4. One of the princes of the French court whom Richelieu had been grooming for future military command was Louis II, the duke of Enghien. The son of the prince of Conde and a cousin of the king, d’Enghien was 21 years old at the time of Richelieu’s death and fourth in line for the throne. Just before this death, Richelieu appointed d’Enghien to serve as commander in chief of all of the forces in northeastern France. Although he was headstrong and prone to mood swings, d’Enghien possessed an innate knack for inspiring soldiers to fight their best.

To capitalize on the death of Richelieu and relieve pressure on other fronts, Melo decided to invade northeastern France. In April 1643, he began assembling five columns for his invasion army. One of the columns, led by General Johann Beck, was ordered to Chateau Regnault on the Meuse River, about a half-day’s march from the French fortress at Rocroi, to guard the main supply line to the Spanish Netherlands.

The rest of Melo’s army, comprising 20,000 infantry and 7,000 Walloon and German cavalry, marched through the rugged Ardennes region, arriving at Rocroi on May 12. Although the fortified town had few resources to offer attackers, it lay astride two major routes to Paris, one through Reims and the other through Soissons. To support a deeper advance into France, it was necessary to eliminate the small French garrison at Rocroi to ensure a safe supply route for future operations.

D’Enghien had taken command in the field, accompanied by two older and experienced generals who Richelieu’s successor, Cardinal Jules Mazarin, believed would offer the young general sound counsel. One was the cautious 60-year-old Marshal Francois de l’Hopital and the other was 34-year-old Jean de Gassion, whose military résumé included having fought under King Gustavus and Protestant General Bernard of Saxe-Weimar. D’Enghien, believing that the time had come for the French to vanquish the Spanish on a field of battle, gathered all the forces at his disposal and marched with 17,000 infantry and 6,000 cavalry to meet Melo’s thrust.

France had 1,000 professional soldiers and 400 militia inside Rocroi when the Spanish began arriving outside the fortress. Faulty intelligence led the Spanish to believe the fortress had fallen into disrepair and might be taken without a lengthy siege. Because of this, the Spanish had brought only 18 guns with them, a small number for such an undertaking. They received a rude shock when the French garrison began shelling Spanish soldiers taking up positions around the fortress. As a result, the Spanish moved cautiously on the fort, and it was not until May 17 that they captured the outer works.

That same day, d’Enghien received notification that King Louis had died and that the Bourbon dynasty was now under the regency of Anne of Austria, the mother of four-year-old King Louis XIV. D’Enghien’s father sent an urgent dispatch to his son in the field requesting that he return to Paris immediately to help ensure a peaceful transfer of power, but the duke disregarded the request, believing the best path toward ensuring the new regime’s stability was through military victory. By then he was within striking distance of Melo’s army. D’Enghien intended to defeat his adversary on the battlefield and force Melo to withdraw to his side of the frontier.

Heading for a Direct Confrontation

On the morning of May 18, d’Enghien held a council of war in which he informed his subordinates that the army would march immediately to the relief of Rocroi and give battle if necessary. L’Hopital objected to the plan, recommending instead that d’Enghien feint with a small force toward Rocroi while leading the main force north to cut Melo’s supply line and force him to break off the invasion. But others, including Gassion, agreed with d’Enghien that the best course of action was a direct confrontation. Ignoring L’Hopital’s advice, d’Enghien ordered an immediate advance on Rocroi.

The fortress was positioned atop a plateau surrounded on all sides by thick forest and low-lying marshes between the headwaters of the Oise River to its west and the Meuse River to its east. The plateau, which offered an open space four miles wide where the two adversaries might maneuver, was approachable only from the west through a narrow defile that provided the perfect place for an ambush.

But Melo had no thought of an ambush. He was eager to meet the French in a head-to-head fight, and he had great confidence in the ability of his tercios to stand any test in the coming battle. Melo ordered a party of 50 Croatian scouts in bright-red cloaks to watch the French advance and inform him of the exact time of the French arrival so that he might reform his army into a new line of battle. Because he expected a pitched battle to unfold the following day, Melo sent orders to Beck to come immediately to his aid.

As the French approached the defile, d’Enghien ordered the baggage and artillery to stay behind so that they would not get in the way if the enemy sprang an ambush. The French cavalry that formed the vanguard of d’Enghien’s army passed through the defile that afternoon and easily brushed aside Melo’s scouts. It then took up a protective position to screen the infantry as it arrived. Enghien’s scouts reported that the Spanish had not constructed an outer trench around Rocroi to defend against a relief force. Instead, they would have to lift their siege and meet the French on the open plain south of the fortress.

While Melo’s foot and horse were redeploying south of the fort into a battle line, General Henri de La Ferte-Senneterre, who shared command of the horse on the French left flank, detached four of his eight cavalry squadrons to ride through the marsh that anchored the Spanish right flank in an attempt to open a supply route to the fort’s garrison. The move, which was made without d’Enghien’s permission, quickly caught the commander in chief’s eye, and he recalled the troops to the main line. The move undoubtedly saved the lives of numerous French cuirassiers who would be needed in battle the following day.

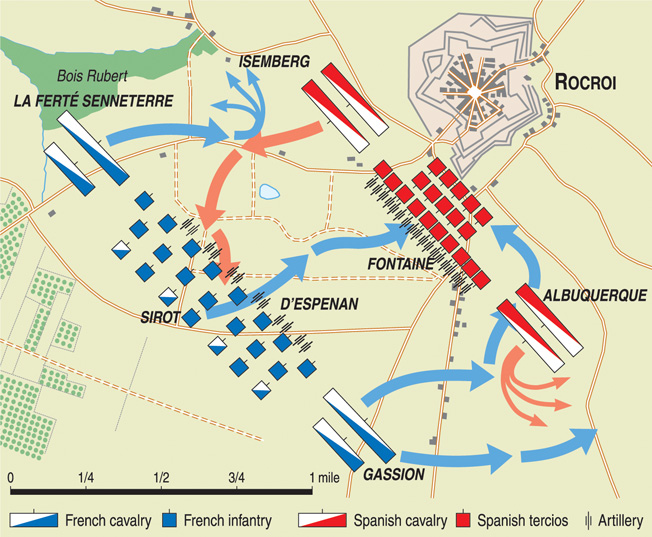

The Spanish Tercios

By nightfall, d’Enghien’s army had finished deploying on the western side of the plateau opposite the Spanish. On the French left flank, La Ferte-Senneterre commanded the first rank of horse, and L’Hopital commanded the second rank. On the opposite flank, Gassion commanded the first rank of horse, while d’Enghien led the second rank. The French infantry was organized into battalions of 850 men each, formed into a line 10 ranks deep. The Marquis d’Espenan commanded the 15 battalions of French foot formed into two divisions in the center, one behind the other. Stationed behind the infantry in a third division was a combined arms reserve comprising of four cavalry squadrons and three infantry battalions. The French placed their 12 guns in front of the infantry.

The two armies were nearly matched in infantry and cavalry on the battlefield. Because Beck’s 4,000-strong column was not present on the battlefield by nightfall on May 18, Melo had about the same number of infantry and cavalry as d’Enghien. Like the French, the Spanish deployed their infantry in the middle and their cavalry on the wings. The German cavalry posted on the right, which was nearest to the fortress of Rocroi, and was led by 53-year-old Count Ernst von Isenberg, who was accustomed to operating independently as commander of Spain’s Army of Alsace. Because Isenberg’s cuirassiers were the last to abandon their siege positions around the fortress, they continued to file into their new position throughout the night.

The Walloon cavalry on the Spanish left opposite Gassion and d’Enghien was led by the rash and quarrelsome 22-year-old Francisco Fernandez de la Cueva, the Duke of Albuquerque, who had been serving in the Army of Flanders for only two years. In the days leading up to the battle, he had quarreled at length with his fellow commanders over various tactical details. His behavior did not bode well for a battle in which both sides would need strong coordination to prevail over the enemy. Technically, at least, Albuquerque commanded the horse on both wings.

The Spanish cavalry was no match for the French cavalry when it came to battlefield performance. Indeed, it had performed so poorly at Honnecourt the year before that the high command of the Army of Flanders had considered disbanding it altogether. Melo therefore was aware that the burden of defeating the enemy would fall to his tercios. At the Battle of Nordlingen a decade before, Spanish foot fighting under the Cardinal-Infante had shown that the tercio formation was still viable despite the tactical improvements introduced by the Dutch and Swedes. In that engagement, the Spanish tercios had held their ground against repeated assaults by Swedish and Protestant German units. The Spanish had vanquished the Swedes at Nordlingen, and they intended to do the same to the French at Rocroi.

The Spanish tercios in the center of the field were led by 68-year-old Paulo Bernard, the Count of Fontaine, who had risen from the ranks and at the time of the battle held the position of the highest-ranking infantry officer in the Army of the Flanders. Fontaine was seriously ill and unable to walk on his own at the time of the battle. For this reason, his aides carried him about the battlefield on a chair. Fontaine’s immobility and the lack of an experienced replacement to relieve him was another glaring problem in the army’s leadership. Rather than showing sympathy for Fontaine’s condition, Albuquerque criticized the old general repeatedly in the days leading up to the battle, and for that reason Fontaine had refused to detach musketeers to increase the firepower of the cavalry stationed on the wings.

Fontaine, who had eight tercios under his command, deployed them in a mile-wide line of battle with a substantial amount of space between each tercio. Each tercio had 70 men in a line that was 20 ranks deep. The far left of the front line of foot was held by the Gramont (Burgundian) tercio and the Strozzi (Italian) tercio, and the far right was anchored by the Visconti (Italian) tercio. Between these were the five Spanish tercios that were considered the rock of the army. A second line of infantry comprised smaller Walloon and German battalions deployed 50 men wide and 10 men deep.

Alvaro Melo, the commander in chief’s younger brother and a former naval officer, commanded the 18 guns placed in front of the infantry. Like Albuquerque, he lacked the kind of experience that would be needed in the coming battle. Because of the bickering between Albuquerque and Fontaine, Melo instructed the latter to detach the 500 musketeers to form an ambush party that took position in the woods on the Spanish left flank. The battle began shortly after they were wiped out by a French force three times their size at 3 am.

After the Spanish ambush had been nullified, d’Enghien gave orders at 4 am for the artillery to begin shelling the enemy line while his foot and horse soldiers arose from their fleeting slumber. The Spanish guns erupted in reply, and the two sides pounded each other as they awaited the first light of dawn and the promise of a terrible battle to follow.

Clash of Cavalry

D’Enghien’s plan, which sought to take advantage of the French cavalry advantage, called for nearly simultaneous attacks at dawn on the Spanish cavalry. Once the Spanish cavalry had been defeated, he intended to have his cuirassiers assail the Spanish tercios from flanks and rear while his infantry pressed it from the front. La Ferte’s horse advanced once there was enough light for the cuirassiers to see where they were going. The advance did not go well. La Ferte’s horsemen became disorganized as they sought to traverse the wet ground at the north end of the battlefield, and when they finally reached Isenberg’s front line, their charge was weak and uneven. Most of La Ferte’s cuirassiers turned around after their failed charge and retreated a safe distance to reform.

Isenberg immediately ordered his cavalry to counterattack before La Ferte’s men had reformed. The German horse advanced at a slow trot and managed to traverse the marshland in an even line. They caught La Ferte’s force in a disorganized state and shattered it like glass. La Ferte’s surviving cavalry desperately fled into the woods to the north. La Ferte was wounded during the fighting and taken prisoner along with a number of his men.

Isenberg’s troops continued their advance and soon became engaged in a general melee with L’Hopital’s second line of horse. The result was the same. The German cuirassiers, who consumed their initial success over La Ferte like a powerful elixir, overwhelmed L’Hopital’s cavalry, and it also fled the field for the safety of the woods rimming the plateau. Although L’Hopital was wounded during the melee, the elderly marshal managed to escape without being captured. Isenberg had smashed both lines of French cavalry with only his first line. Sensing that they had won the first phase of the battle, the Spanish infantry began throwing their hats in the air and cheering. It was a premature reaction, as events would show.

Some of Isenberg’s cuirassiers rode west in search of the French baggage, and others milled about the French left flank awaiting further instructions. At that point, Isenberg ordered his second line to advance. Once they had reached the French line, he ordered cuirassiers from both echelons to wheel and strike the French infantry in its left flank. To support this effort, Fontaine ordered his two right units to engage the French infantry. The French recoiled from the advance of Melo’s tercios, believing a general advance was under way. Most of the French cannons fell into Spanish hands.

Driving the German Cavalry Back

To check the assault by the German horse on the French left flank, Baron Claude Sirot ordered the 800 cuirassiers from the French reserve to attack Isenberg’s right flank. It was an effective move, and the fresh French horse quickly blunted Isenberg’s attack and forced him to redeploy some of his squadrons to meet the new threat. Gassion led the seven horse squadrons of the first echelon on the French right wing forward at the same time that La Ferte led his cuirassiers forward on the opposite wing. Gassion’s advance was checked by Albuquerque’s first echelon, which promptly countercharged in an effort to drive back the French.

From his position on a rise, d’Enghien observed the swirling melee in front of him. He sported a wide-brimmed hat with enormous white plumes so that his men could easily spot him on the battlefield and take heart that he was among them in the thick of the fight. The Walloon cavalry fought valiantly in the opening moments of the battle, despite heavy fire from French muskets hidden in the woods to their left that toppled Spanish cuirassiers from their saddles.

Sensing the moment was right to drive back the Walloon horse, d’Enghien waved forward the eight squadrons that formed the second echelon to advance at a slow trot toward the enemy position. The combined weight of the two echelons of French cavalry was sufficient to snap the spine of the Walloon cavalry, and the survivors fled east, carrying with them their young commander. Albuquerque spent the rest of the battle riding to and fro trying in vain to rally small groups of cavalry. Meanwhile, the Strozzi tercio, which anchored the left end of Fontaine’s battle line, had advanced to assist Albuquerque’s attack. In the process, it had invited attack from the French cavalry, which drove it from the field in disorder.

D’Enghien sought out Gassion on the field, and the two kindred souls discussed how they might press their advantage. D’Enghien told Gassion to take one-third of the horsemen and reconnoiter the enemy rear to see if Beck’s column was nearing the battlefield. At the same time, d’Enghien took the other two-thirds of the French cavalry and drove off the German and Walloon foot that formed Melo’s meager reserve. The move was a conscious decision on d’Engien’s part to isolate the stronger Spanish tercios as the battle progressed.

The cuirassiers on the French right wing wheeled left and charged the hapless German and Walloon foot soldiers. The battalions that formed the second echelon of Fontaine’s infantry were arrayed in thin ranks and had fewer pikemen than their counterparts in the Spanish foot. These factors made it impossible for them to stand their ground against d’Enghien’s cavalry. The French horse caught the enemy’s second echelon in the flank and smashed each formation in turn.

By 7 am, d’Enghien had scattered the second echelon of Fontaine’s infantry and arrived at the north end of the battlefield squarely behind Isenberg’s cavalry. While he reformed his horse squadrons to assault Isenberg’s cavalry, elements of L’Hopital’s horse emerged from the cover of the woods and rejoined the battle. At that point, Isenberg’s men were still engaged with Sirot’s cavalry and musketeers and, therefore, were unable to turn and meet d’Enghien’s charge. Isenberg soon found himself under attack from three directions. The German cavalry fought desperately to extract itself from the uneven fight, but they lost all cohesion as a fighting force and individual riders fled into the swamp or woods as L’Hopital’s horsemen had done before them. Isenberg was badly wounded in the melee, but managed to escape with his life.

“Here I Wish to Die With the Italian Gentlemen”

Melo’s performance on the field was completely eclipsed by d’Enghien’s leadership. The Spanish commander spent the first two hours of the battle riding back and forth between the two wings, trying to rally retreating horse squadrons. By so doing, he exposed himself to capture or death. His army would have been better served if he had remained at a safe distance from which he could dispatch orders and receive reports from various sectors of the battlefield.

With the French cavalry roaming the field largely uncontested, Melo had no choice but to seek refuge with one of his tercios. At the time d’Enghien reached the Spanish right wing and charged Isenberg’s cavalry, Melo happened to be in the same area. He rode into the midst of the Visconti tercio. “Here I wish to die with the Italian gentlemen,” he said. Those were the words of a beaten general who had already given up the fight.

No sooner had Melo uttered these words than the French attacked Fontaine’s two forward tercios from three sides. For the three hours since dawn, the fighting had mainly involved opposing cavalry forces. Now the battle entered its final, protracted phase. By 8 am, the Spanish infantry was fighting for its survival against all three arms of the French army. The Visconti and Velandia tercios on the Spanish right flank found themselves under steady fire from French musket formations that poured heavy volleys into their ranks. The two Spanish tercios had begun the battle with nearly 3,000 men between them, but after more than an hour of fighting, their ranks were greatly depleted. Still, they maintained their cohesion, and the survivors were able to gradually withdraw from the battle. The orderly withdrawal of the Italian tercios also made it possible for Melo to slip quietly away from the battle and avoid capture.

Fontaine resolved to stand firm on the battlefield despite having witnessed the decimation of three of the eight tercios under his command. An experienced commander, he weighed the pros and cons of holding his position or of conducting a fighting withdrawal, a difficult maneuver in the best of circumstances. He chose to stand and fight. Perhaps he believed that Beck’s fresh column would arrive and help check or drive back the French. Or perhaps he believed that his veterans were better soldiers than the French and could defeat them in a head-to-head fight. Both were plausible assumptions—neither happened.

Breaching the Spanish Squares

The five remaining tercios—four Spanish and one Burgundian—totaled about 8,000 men. Knowing that they were outnumbered by more than two-to-one by the French, Fontaine ordered them to form a massive square to serve as a four-sided bulwark capable of defending itself against attacks from all directions. The Spanish artillerymen abandoned their cannons, which had run out of gunpowder. To fend off cavalry attacks, the pikemen moved to the front and thrust their long staffs out to protect the musketeers.

To prevent the Spanish from reinforcing the front of the square with fresh troops, d’Enghien issued orders for his generals to deploy their forces on all sides of the square. Still fearing the imminent arrival of Beck’s column, the French commander in chief made immediate preparations to attack the square. The Spanish infantry’s ability to maintain the square while under repeated attacks from the French was a tribute to the training and discipline that had made it the most formidable infantry in western Europe for the past 100 years. Three times the French advanced; each time they were driven back by concentrated musket fire delivered at close range.

Although the attacks failed, they brought about a crisis of command when French fire struck and killed Fontaine, who had been directing the Spanish square from a raised chair in which he was being carried. At that point, a colonel commanding one of the veteran tercios assumed command. While the first attacks against the Spanish square were in progress, Gassion located and sacked the Spanish baggage train, which ensured that the enemy infantry would not be able to replenish its ammunition.

Beck’s column had marched 17 miles on the day of the battle but had halted five miles from Rocroi at the village of Philippeville. As he neared Rocroi at 9 am, Beck met dispirited Walloons and Germans fleeing the battle. They informed him that Melo’s army was already beaten and that the day was lost. Rather than reconnoitering himself or sending his scouts to verify the information, Beck was content to spend the rest of the day rounding up fugitives in preparation for a withdrawal the following day.

After its initial repulse, d’Enghien let his men pause long enough for the supporting columns led by L’Hopital, Sirot, and Gassion to get into position to assault the square from various directions. The French pikemen were ordered to remain in reserve while the generals organized mounted troops and muskets into light formations capable of inflicting heavy losses on the square and weaken it for the pikemen.

At 9 am, the French forces converged on the enemy’s square from all directions. D’Enghien ordered the French artillerymen to load their guns with grapeshot and fire on the square at point-blank range to open gaps that the cavalry might exploit. Added to this was close-range fire from French muskets and cavalrymen armed with wheel-lock pistols. Three times the cavalry charged the square from all four directions, but each time it was driven off. When a lull occurred in the fighting, the French called for the Spanish to surrender. The Spanish foot declined the invitation.

Eventually the shell and shot took its toll on the outer ranks of the square manned by the pikemen. When the perimeter began to crumble and the musketeers ran low on ammunition, the colonel in charge of the remaining Spanish infantry signaled the French at 9:30 am that he wanted to negotiate terms of surrender.

A Bloody Surrender

D’Enghien assembled his staff, and they rode toward the Spanish lines. Not all of the Spanish were aware that their commander had offered to surrender. A number of Spanish musketeers believed that the approaching group of cavalry was the beginning of a fresh charge, and when d’Enghien and his escort came within musket range, they were greeted by a hail of bullets. The result was disastrous. The French troops were outraged that the Spanish had violated the truce, and they launched a final, all-out attack on the Spanish square. The square was broken by the fury of the French attack, and the Spanish broke up into small bands trying to protect themselves from being massacred.

D’Enghien quickly grasped that the enemy had fired on his party by mistake. He shouted to his men to break off the attack, but to no avail. The Spanish troops nearest to d’Enghien threw down their weapons and clung to his horse and stirrups, begging for quarter. After another half hour of fighting, the battle at last was over. Where the Spanish had a short time before stood tall and defiant in their squares, hundreds of prone and contorted bodies now lay slain by the victorious French on the plateau of Rocroi.

The Spanish lost 8,000 killed and 7,500 captured. In contrast, the French lost 2,000 killed. Most of those captured were exchanged two months later for Spanish prisoners taken at Honnecourt. About 4,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry, many of whom were wounded, were able to escape the battlefield and join Beck’s corps at Philippeville. Melo, who dropped his marshal’s baton on the battlefield in his flight to escape capture, joined Beck, Albuquerque, and Isenberg. The greatly reduced Spanish army retreated on May 20.

Spain Goes on the Defensive

Enghien failed to capitalize on his decisive victory at Rocroi by either eliminating the smaller Spanish army or invading the Spanish Netherlands. Instead, he laid siege to the fortress of Thionville in Lorraine, just inside the Holy Roman Empire. Beck anticipated the move and sent 2,000 men to reinforce the fort’s garrison of 800 troops. Nevertheless, d’Enghien forced the garrison to capitulate on August 10 after a long siege.

Lacking funds and manpower to wage an offensive war against France, the Spanish maintained a defensive posture the following year, content to hold on to a string of imposing forts that kept the French at bay. Despite the losses suffered at Rocroi, the Army of Flanders still had a total strength of 78,000 in December 1643. The war would go on—except for the men who had fallen at Rocroi, where the flower of the Spanish army had died upholding its reputation as the finest fighting force in the world. In the end, such a reputation was not enough.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments