By David Lippman

In the distance, they could see the jagged flashes of lightning, an incoming squall in the dark. Just before the rain arrived, so did St. Elmo’s Fire, and the gun barrels and radio antennas on the PT boats crackled with blue sparks and streamers of static electricity.

Then there was another lightning flash, and suddenly Lieutenant (j.g.) Terry Chambers, the executive officer of PT-491 saw them—a column of seven Japanese warships advancing in the dark, headed for Surigao Strait and the waiting U.S. Seventh Fleet. It was the extremely early morning of October 25, 1944, and two battleships and a heavy cruiser of the Imperial Japanese Navy were steaming toward what would become one of the most one-sided battles in naval history, and the last duel between battleships of the line.

The Battle of Surigao Strait was a major portion of the titanic Battle of Leyte Gulf, the largest and last major naval battle ever fought, an epic engagement that saw the use of every type of naval warfare except the mine.

The Leyte Gulf battle began with the American decision on July 27, 1944, to target the Philippines instead of Formosa as their next invasion site. General Douglas MacArthur would redeem his pledge to return to the Philippines. The initial objective was the invasion of the island of Leyte to secure air and sea bases for the next stages: seizing Mindoro and the climactic assault on the main island of Luzon.

Codenamed King II, the invasion of Leyte would involve two U.S. fleets, the 7th, under Vice Admiral Thomas Cassin Kinkaid, and the 3rd, under Vice Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr.

Sho-1: The Imperial Navy Strikes Back

The 3rd Fleet was the offensive arm of the invasion, with nine fleet carriers, eight light carriers, and six fast battleships at its heart. The 7th Fleet was the amphibious force, with more than 100 transports and other vessels (including the British minelayer HMS Ariadne), protected by a swarm of cruisers, destroyers, and escort carriers for close air support, backed by six old battleships configured for shore bombardment, in a Fire Support Force, headed by Rear Admiral Jesse B. Oldendorf, flying his flag in the heavy cruiser USS Louisville. Among his ships were the Australian cruiser HMAS Shropshire and the destroyer HMAS Arunta. A-day for the invasion was to be October 20, 1944.

The invaders were not spotted by the Japanese until October 17, when the whole American armada appeared at the mouth of the Gulf of Leyte. When they did so, Admiral Soemu Toyoda, who headed the Imperial Japanese Navy, ordered their long-planned response, Victory Operation One, or Sho-1, into operation.

Sho-1 was one of four plans the Japanese had prepared in anticipation of America’s next offensive move, and they all called for the same reaction: the bulk of the Imperial Japanese Navy steaming forth to attack and destroy the U.S. fleet, regardless of losses to themselves.

Sho-1 was like most Imperial Japanese Navy plans of World War II: a decoy force would lure the Americans in one direction, while the real punch would come from other directions in a complex series of coordinated movements. This time, the decoy force was Japan’s surviving aircraft carriers, under Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa, steaming down from the home islands. With barely 100 planes between them, these carriers lacked offensive punch, but the Japanese believed the aggressive Halsey would race after them with his entire 3rd Fleet.

While Halsey was drawn off, the powerful battleships and heavy cruisers of the Imperial Navy, mostly based at Lingga Roads near Singapore and the Borneo fuel stocks, would strike east and ravage the 7th Fleet’s amphibious forces while they lay in Leyte Gulf. The surface ships would pound the 7th Fleet to death with torpedoes and shells, isolating the American invaders on shore. The combination of a trapped army in the Philippines and a smashed navy in the Pacific might at least buy Japan time, or even persuade America to make peace.

The Task Forces of Kurita and Nishimura

The battlewagons at Lingga were commanded by Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita and consisted of a powerful force. They were headed by two immense dreadnoughts, the Yamato and Musashi, sister ships that packed the heaviest armament ever loaded on a battleship, 18.1-inch guns. They were supported by five more dreadnoughts and a screen of cruisers and destroyers, all of which brandished the legendary Type 95 Long Lance torpedo, one of the best in the world. The Imperial Japanese Navy may have been worn down by hard war, but it was still a powerful force with highly skilled sailors and officers well trained in night fighting.

Toyoda and Kurita planned a pincer attack on Leyte Gulf with their battleships. Kurita would take one force, with five battleships, including Yamato and Musashi, through the San Bernardino Strait to hit Leyte Gulf from the north. A second force, under Vice Admiral Shoji Nishimura, a veteran seadog, would steam through the Surigao Strait and smash into Leyte Gulf from the south, the anvil to Kurita’s hammer, just before dawn.

A Naval War College graduate of 1911, Nishimura had commanded destroyers in the invasion of the Philippines and the Dutch East Indies in 1941. His son, Teiji Nishimura, a naval aviator, had been killed in the former invasion. In 1942, Nishimura commanded cruisers in the grueling struggle for Guadalcanal, suffering some bad luck but displaying skillful planning and “lion-like fury” in battle.

On September 10, 1944, Nishimura was given command of Battleship Division 2, which consisted of the dreadnoughts Fuso and Yamashiro and their destroyer escorts. The two battlewagons, sister ships, dated back to 1911 and were known throughout the fleet for their tall pagoda masts—44 meters above the waterline—and for having sat out most of the war in home waters, mostly as training vessels. The emperor’s brother had served on Fuso twice.

These battleships had never fired their guns in anger. They were the first battleships built with Japanese engines and guns, the most powerful dreadnoughts in the world at the time. But Fuso and Yamashiro were slow and outdated by 1944’s standards, armed with six 14-inch guns each. They were sister ships, but not twins, and regarded as the “ugliest ships in the Imperial Navy.” Both had crews of about 1,600 officers and men. Yamashiro flew Nishimura’s flag.

To support Nishimura’s force would be four destroyers, Michishio, Yamagumo, Asagumo, and Shigure, and a veteran heavy cruiser, the Mogami.

Failed Coordination With the Second Striking Force

Studying his war maps, Toyoda did not think that Nishimura had quite enough punch, so he added a second task force to the southern wing, under Vice Admiral Kiyohide Shima, swinging down from the Pescadore Islands off Formosa. The second striking force would consist of the heavy cruisers Nachi and Ashigara, both veteran ships; the light cruiser Abukuma, which had escorted Japan’s carriers to Pearl Harbor; and four destroyers, Shiranuhi, Kasumi, Ushio, and Akebono.

Unlike Nishimura, Shima was a desk sailor. Like Nishimura, Shima had graduated from the Naval War College in the class of 1911. He had served in a variety of shore posts, mostly in communications.

Neither force commander coordinated his movements with the other—nor were any orders given to do so. Neither commander was fully briefed about the other’s operations. As far as historians could tell, Nishimura was to clear a path with his battleships so that the cruisers and destroyers behind could finish off the transports with torpedoes. Nishimura’s group was to be called the Third Section, while Shima’s group was the Second Striking Force.

With the Americans moving on Leyte, the Japanese launched their intricate countermoves. Ozawa sortied from Japan, Shima from the Pescadores, and Kurita and Nishimura from Lingga Roads, headed for a refueling stop at Brunei.

On October 20, the Americans invaded Leyte with massive power. Landings began at 10 am, and General MacArthur strode grimly ashore four hours later, making his famous “I have returned!” speech from the invasion beach amid a steady downpour.

Spotted in the Sulu Sea

The next day, Kurita summoned his senior officers to a conference on his flagship, the heavy cruiser Atago. Kurita explained his plans to the assembled admirals, including the decision to split off Nishimura’s force to head for the Surigao Strait. If the complex ship movements worked, the two forces would slam into the American 7th Fleet just before dawn on October 25. The next morning, the Imperial Japanese Navy’s battle line headed out for sea for the very last time, with Kurita and his five dreadnoughts steaming north to the Sibuyan Sea and the San Bernardino Strait.

At 3:30 pm, Nishimura’s ships put to sea. Shima’s ships were already en route. All through the afternoon and night, the two forces steamed along unimpeded into the Sulu Sea. Not so Kurita’s force, which was spotted by two American submarines, which slapped torpedoes into three of Kurita’s cruisers, sinking two—including his flagship Atago—and damaging the third. Kurita shifted his flag to the battleship Yamato and sailed on.

At 6 am on the morning of October 24, the nearest carriers to Nishimura, the veteran USS Enterprise and the new USS Franklin, launched reconnaissance planes to fan out over the Sulu Sea, hunting for Japanese warships.

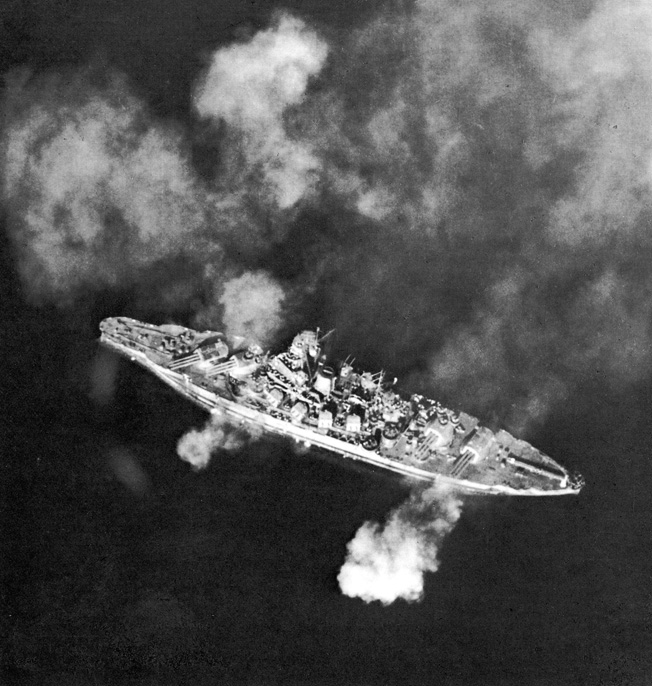

At 8:30 am, an Enterprise search team under Lieutenant Raymond E. Moore spotted Nishimura’s battleships and identified them correctly. A strike group of 12 bombers and 16 fighters headed for the dreadnoughts. For Enterprise Ensign Robert J. Barnes, seeing the massive battleships beneath him was “something you dream about as a dive-bomber pilot. The antiaircraft fire was terrific.”

On the Japanese ships, signal halyards and bugle calls summoned everyone to battle stations; the 14-inch guns loaded Type 3 antiaircraft ammunition and opened fire. The barrage of shells shook Asagumo’s chief engineer, Tokichi Ishii, in his engine room. On Fuso, Yeoman 2nd Class Hideo Ogawa, in the powder magazine, considered that if the battleship were hit his end would be quick, as he was surrounded by main battery powder canisters.

The American planes swooped down on the Japanese warships, subjecting them to bombing, strafing, and rockets. On Yamashiro, 20 men died from strafing. A bomb scored a direct hit on Fuso, bouncing No. 1 turret on its barbette. It crashed through the deck and killed everyone in the secondary battery. Another bomb hit Fuso’s quarterdeck, setting two floatplanes ablaze and gutting the wardroom. Another bomb grazed the Shigure’s No. 1 turret.

Lieutenant Commander Fred Bakutis, skipper of Enterprise’s fighter squadron, was shot out of the sky during the battle and had to ditch. Luckily, the Japanese did not spot him, and he spent seven days in a life raft before he was spotted and picked up by the submarine USS Hardhead, dehydrated, hungry, blistered, but otherwise in good shape. He recovered to resume flying.

The American planes flew off, and damage control parties on the Japanese ships went to work. Both battlewagons suffered from burst seams and minor damage. Nishimura ordered his ships to proceed with their mission. He fired off Mogami’s scout planes to check on the enemy. One of them reported four battleships, two cruisers, four destroyers, 15 aircraft carriers, 14 PT boats, and 80 transports in Leyte Gulf, a close approximation of the defense. At 4 pm, Nishimura blinkered his battle plan. Mogami and the four destroyers would steam ahead and mop up the enemy PT boats, then reassemble, and all ships would charge up Surigao Strait.

Oldendorf’s Advantages and Disadvantages

Meanwhile, the Americans, aware of Nishimura’s advance, made their preparations. Rear Admiral Jesse C. Oldendorf was a burly Californian and a member of the Annapolis class of 1909. Known as “Oley” to his pals, he had commanded the heavy cruiser USS Houston before the war, which had carried President Franklin D. Roosevelt on his voyages. In 1942 and 1943, he was in charge of countermeasures in the Caribbean against U-boats and screening big transports on convoy duty. He took over the Pacific Fleet’s gunfire support battleships in 1944, flying his flag on the heavy cruiser USS Louisville.

With short notice, Oldendorf planned his defenses with skill. He summoned his subordinate admirals aboard his flagship in the early evening to lay out his plans. He had several advantages: large numbers of ships, new fire-control radar, combat information centers to channel information flow in and orders out, and above all the narrow geography of Surigao Strait, which offered opportunities for ambushes. He set up a gauntlet for the Japanese. PT boats would be the opening screen, alerting Oldendorf to the enemy’s location, size, and movements. Then Oldendorf would harry them with destroyers armed with torpedoes. The Japanese would be worn down by the time they reached his battle line of six older battlewagons and 10 cruisers, which included Australia’s HMAS Shropshire.

The crowded nature of Surigao Strait would enable Oldendorf to form a battle line “crossing the T” of the Japanese advance, the dream of every naval commander, which would hammer the Japanese ships.

Still, the U.S. Navy had not shown a good record in night naval engagements up to this point, losing battles or suffering heavy casualties in the Solomons. His destroyers lacked replacement torpedoes. The American battleships were not the Navy’s first team of fast dreadnoughts, but older, slower vessels, built just after World War I. At least two lacked modern radar.

Most importantly, Oldendorf’s ships’ ammunition scales were for providing support fire for ground troops. They had been doing so for days. Some of the destroyers were down to 20 percent of their ammunition. The battleships were loaded with 77 percent bombardment shells for ground targets and 23 percent armorpiercing ordnance for enemy ships—and they had been on the bombardment line for days, shooting off 58 percent of all their ammunition. Oldendorf told his battleship men to hold fire until the Japanese had closed to 17,000 to 20,000 yards, use armor-piercing shells to rip open the enemy hulls, and high explosive ordnance thereafter.

Oldendorf took other precautions. Remembering that at Savo Island in 1942, Japanese shells blasted American cruisers’ seaplanes to start fires, he ordered his ships to park their seaplanes in hangars and rely on PT boats, radar, and good communications to track the enemy. The destroyers and cruisers took up positions on the right and left wings of the battle line to minimize the risk of friendly fire. All afternoon, Oldendorf’s ships took on additional ammunition.

PT Boats Make Contact

Everybody in the American force was eager for battle. Five of the battleships in Oldendorf’s line had been present at Pearl Harbor: Maryland, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, California, and Tennessee. Their crews were eager to avenge that humiliation. The sixth battleship was the veteran USS Mississippi. Some of the American cruisers were new warships, like Denver, Columbia, and Cleveland, while others trailed lengthy records of combat. Portland had been at Midway, Minneapolis at Guadalcanal, Phoenix had steamed boldly out of the carnage of Pearl Harbor, while Boise survived overwhelming Japanese power in the defeats in the Philippines and Dutch East Indies. The Australians aboard HMAS Shropshire had bitter memories of the fiasco at Savo Island, having served aboard and survived the sinking of HMAS Canberra before she could fire a shot.

Captain Jesse G. Coward, a Guadalcanal veteran commanding Destroyer Squadron (Desron) 54, a fresh addition to Oldendorf’s force, signaled his boss: “In case of surface contact to the southward I plan to make an immediate torpedo attack and then retire to clear you. With your approval I will submit plan shortly.” Oldendorf gave the aggressive Coward the green light 15 minutes later.

The Japanese were going in, too. Nishimura intended to hit the American transports at 4 am. The night wore on, with Japanese lookouts peering into the dark as the two forces moved separately through the Mindanao Sea and toward the island of Leyte.

Waiting in the dark for Nishimura’s split force were 39 PT boats in 13 groups of three, engines idling, ready to fire torpedoes and crash start their main engines to escape. There was no wind, a flat sea, and visibility only about three miles. Aboard Louisville, Oldendorf could only see two ships in front of and behind him.

At 10:36 pm, Ensign Peter R. Gadd’s PT-131 spotted the Japanese force on its radar. Gadd throttled up and closed in to attack, joined by other PT boats. To their amazement, they saw the immense bulks of Nishimura’s capital ships heading north. The PT boats headed in to loose torpedoes, and lookouts on Shigure spotted the American vessels. Shigure opened fire and illuminated with starshells.

Realizing they were attacking a force many times their power, the PT boats turned away, making smoke to obscure their exits. The battleships joined in with their secondary armament. One 6-inch shell struck a glancing blow right against the forward torpedo in its rack on PT-130, smashing the nose, splintering the deck. The shell knocked out the PT boat’s radio and flew out of the bow without detonating.

The PT boats reported their contact up the chain of command, and Oldendorf got the messages an hour and a half after the Japanese were sighted.

The PTs Continue Their Harassment

Meanwhile, the terrier-like PT boats kept connected with the advancing Japanese force. Two PT boats fired torpedoes at Nishimura’s ships but missed. Neither side scored hits, but the scrapping frayed Japanese nerves.

Nishimura was afraid that Mogami would mistake him for the enemy in the deteriorating visibility. Sure enough, at 1:05 am, Fuso lookouts saw a suspicious silhouette off the port bow. Trained in recognizing enemy ships, but not to distinguish Japanese vessels, they reported the silhouette as American. The battleship hurled 6-inch shells in that direction and got an angry voice-radio message back, “Cease firing, cease firing! Friendly ships!” It was Mogami. Unfortunately, just as the message got transmitted, another 6-inch shell hit the cruiser, killing three sailors who were lying in sickbay, wounded in the morning’s American air attack.

Nishimura ordered his ships to cease fire, and the entire Japanese formation regrouped and resumed heading north with the battleships in the lead and Mogami behind. Some distance behind them, Shima’s cruisers followed, his intentions vague. Shima had no plan to cooperate with Nishimura, merely to follow along.

The American PT boats were still harrying the Japanese, though. Next up, PT-134, commanded by Lieutenant Edmund F. Wakelin, got to within 2,500 yards of Nishimura’s ships before coming under Japanese searchlights and gunfire. Wakelin fired torpedoes at Fuso, but they passed harmlessly astern of the battleship. Three more PT boats popped out, and Nishimura had to do some fancy maneuvering to avoid the American fish.

PT-490 found itself a bare 400 yards from the Japanese ships and was hit by two shells. Other shells hit PT-493, damaging the engine, tearing a hole in the boat’s bottom. PT-491 moved in to evacuate the crew, and the wounded PT-493 drifted free and sank after sunrise. American casualties on the fragile PT boats numbered three killed and 20 wounded.

At 2:11 am, Nishimura ordered his ships into battle formation for the dash up the strait. As they did so, another group of PT boats sprinted in from the southeast, hurling six torpedoes at the Japanese. The torpedoes all missed. Nishimura’s ships steamed on at 20 knots.

“Brilliantly Conceived and Well Executed”

Now came Captain Coward’s Desron 54. The sea was glassy and the temperature about 80 degrees Farenheit, and only the wind made by the tin cans’ speed brought relief to the men topside. All hands were served coffee and sandwiches after midnight.

Moving in two flanking groups south through the strait, Coward’s five destroyers plotted the Japanese approach with their radar. At 2:58 am, Shigure illuminated Coward’s eastern group with a searchlight, and Coward assigned targets as his tin cans cranked up to 30 knots for an attack. His plan was to use torpedoes only, so as not to give away his ships’ positions with gun flashes. At 3 am, the American destroyers loosed 27 torpedoes at a range of 11,500 yards at the Japanese.

As the torpedoes powered through the water, Fuso opened up with her 14-inch guns at a surface target for the first time in her life. Petty Officer Hideo Ogawa removed cordite charges from flash-proof storage canisters and loaded them onto the powder-cage elevator, and at 3:07 Fuso let loose at her targets. Japanese shells flew at the American destroyers. A minute later, two American torpedoes from Melvin slammed into Fuso’s starboard side with towering explosions and cascades of water. The dreadnought slowed down and began listing to starboard.

The starboard boiler rooms flooded rapidly. The dreadnought sheered out of line, her starboard side blazing. Incredibly, her skipper, Rear Admiral Masami Ban, did not radio a damage report—he may have been unable to do so or coping with too many crises at once—and her companions continued steaming north. Mogami slipped into the position Fuso vacated. Nishimura was unaware that he had just lost 50 percent of his dreadnought strength and pressed on, radioing orders to an unresponsive Fuso.

Coward’s destroyers charged in, illuminated by a Japanese parachute flare from one of Yamashiro’s floatplanes. As their torpedoes streaked off, Chief Petty Officer Virgil Rollins, manning McDermut’s No. 2 torpedo mount, calmly remarked, “It is about time for something to happen.”

At that instant, 3:20 am, explosions and fireballs lit up the night. Two torpedoes crashed into Yamagumo’s port side, and the destroyer exploded immediately, the blast seen as far away as Oldendorf’s battleships. The hits apparently cooked off Yamagumo’s torpedoes, and the destroyer sank rapidly.

The destruction was only beginning. At 3:22, a torpedo slammed into Yamashiro’s port side. At 3:25, Asagumo took a torpedo hit forward. A startling vibration shook up Chief Engineer Tokichi Ishii. He phoned the bridge to find out what was going on but got no answer. Seconds later, a runner from the bridge appeared bearing word from the skipper, Commander Kazuo Shibayama, to check on a torpedo hit to the port bow. At the same time, torpedoes smacked into Asagumo. She rapidly took on water, her bows shredded.

The Japanese now had only one battleship, one cruiser, and one destroyer ready to hit back, and as Michishio prepared to launch torpedoes, she suddenly heaved and shuddered violently, slowing to a dead halt, the recipient of more American torpedoes from McDermut and Monssen. All power on the Japanese destroyer went out, and the machinery spaces began flooding rapidly.

For the American destroyers, it was a grand slam unmatched in nautical history: three Japanese destroyers and a battleship crippled by a single onslaught of torpedoes. Oldendorf’s report on the attack was blunt and accurate: “Brilliantly conceived and well executed.”

Disaster on the Radio Chatter

In the strait, Japanese warships blazed and began to founder. On Yamashiro’s flag bridge, Nishimura tried to make sense of the rapidly unfolding disaster. He reported by radio to his superiors: “Enemy DDs and torpedo boats are stationed at the northern entrance to Surigao Strait. Two of our DDs have received torpedo damage and are drifting. Yamashiro has been hit by one torpedo, but her battle integrity is not impaired.”

Tokyo got the word. So did USS Denver, which picked up the message at 3 am. It clearly indicated that Nishimura was losing control of the situation. He seemed to assume that Fuso was still following him. The surviving Japanese pressed on.

On Fuso’s bridge, Rear Admiral Ban took stock of disastrous damage control reports: “No. 1 powder and shell magazines filling with water … the ship making only 10 knots … her bow drooping into the water … communications out.” At 3:20, Fuso wobbled onto a westerly course.

Behind this scene of nautical destruction, Shima’s force continued to steam north at maximum battle speed. On the flag bridge of Nachi, Shima listened uneasily to the tactical radio and Japanese voices announcing disaster. He peered out his windows into darkness and rain, wondering what was out there.

Shima’s Task Force Struck

What was out there was Panaon Island. His ships were steaming through rain and mist on the wrong course. At the last minute, lookouts saw mountains looming and heard waves crashing ashore and shouted warnings. Shima ordered his ships to a maximum port turn, and he evaded both navigational embarrassment and disaster. At 3:20, they faced disaster at enemy hands as torpedoes crashed out of the night and into the light cruiser Abukuma’s port side just forward of the bridge, ripping open the flimsy ship’s hull. A thousand tons of water cascaded in.

Shima had just met the American PT boats that had not engaged Nishimura’s ships, and they were eager to tear into the Japanese. Abukuma and her escorts fired back, but to no avail. It was clear Abukuma could not proceed, and the old cruiser pulled out of formation with 37 dead. The cruiser’s escorts sprinted on in the night, leaving Abukuma behind to tend her wounds.

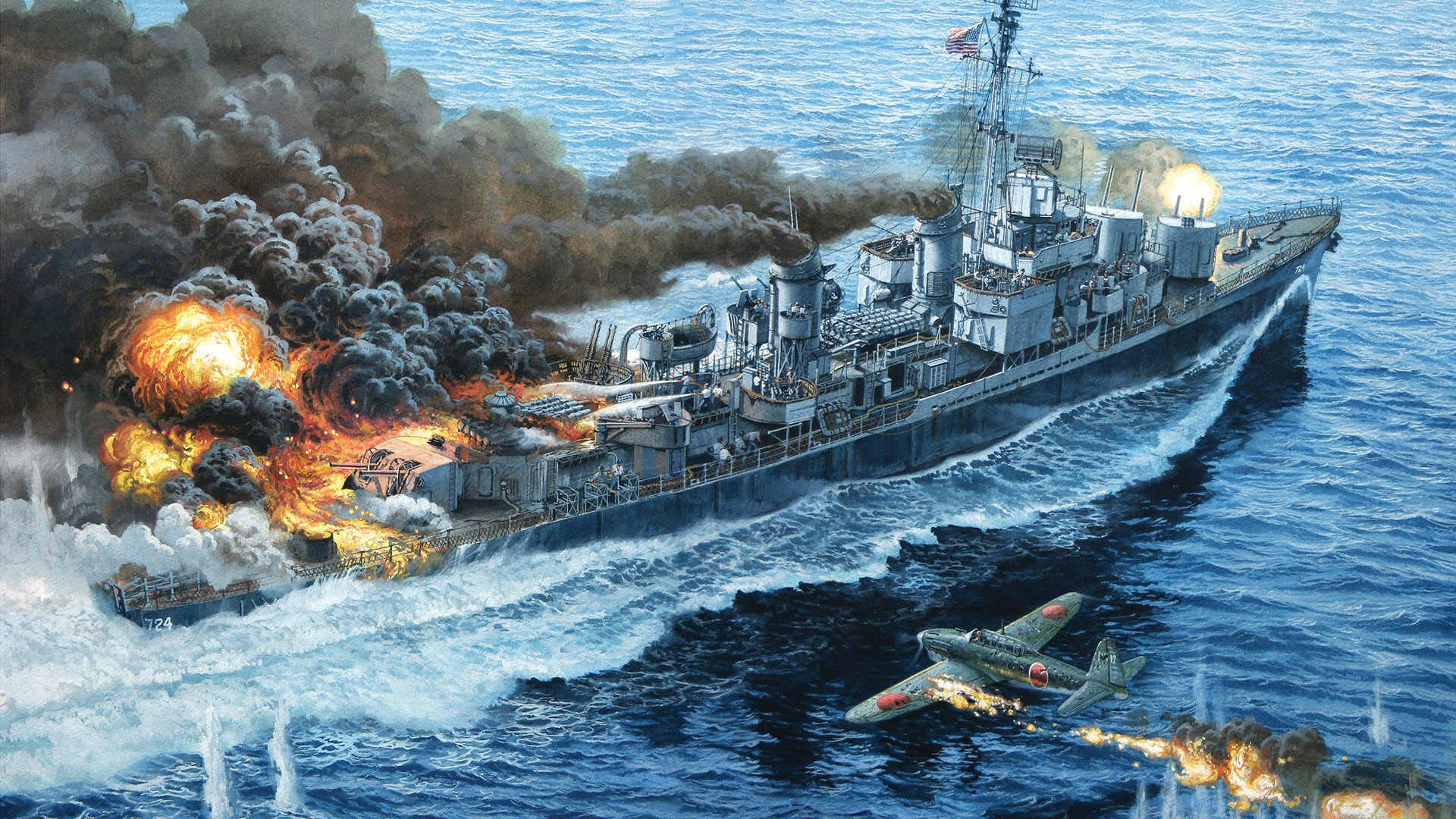

Up ahead, Nishimura’s force continued north. The next set of picadors was Captain Kenmore McManes’s Destroyer Squadron 24 (Desron 24), which included HMAS Arunta, her white ensigns snapping in the wind. Unlike seadogs of old, McManes fought this battle not from his flag bridge but in his combat information center hunched over a radar screen. McManes cranked his ships up to 25 knots, and at 3:23 am, Arunta opened up with five torpedoes.

USS Killen launched her fish a minute later, all aimed at Shigure and Yamashiro. At 3:31, one of Killen’s torpedoes smacked into Yamashiro’s port side amidships. The battleship began to list to port and cut speed to a perilously slow five knots. Determined damage control on the dreadnought patched the holes, and soon Yamashiro was back at a decent 18 knots.

South of the flagship, Fuso was in agony, still moving on a wobbly course, probably trying to beach on Kanihaan Island. But the ship was so far down at the bow, Chief Engineer Captain Eiichi Nakaya could not maintain navigability. In No. 1 turret, Yasuo Kato saw water flooding in from the hatch above him. Kato sent a messenger to the bridge to report his predicament. The messenger saluted, scrambled out of the listing turret, and was back moments later. He could not walk the deck. It was spouting steam, oil, and seawater.

Below Kato, Hideo Ogawa and his pals watched seawater trickle into their space. The turret captain ordered Ogawa and 10 of his buddies to evacuate upward. They climbed into the projectile room above, closing the steel hatch behind them to preserve watertight integrity. Once there, Ogawa and his shipmates kept climbing, joining 15 more men to evacuate through another steel door of the hoist. Then came orders from the bridge: all hands of No. 1 and No. 2 turrets were to assemble at the center starboard upper deck as reserves for damage control.

“Abandon Ship!”

McManes and his tin cans of Desron 24 were still harrying Nishimura’s battered ships. Radar screens were full of pips, from both friend and foe. While the Americans held the initiative, the Japanese fought back. Asagumo fired torpedoes at USS Daly, which sizzled just under the American’s bow.

The sound and fury in this portion of the engagement signified nothing as both sides missed each other, but Fuso’s nightmare was coming to an end. Hideo Ogawa watched his ship’s forecastle slide underwater. Crewmen struggled out of No. 1 turret onto the slanting foredeck, her gunhouse parting the seas with its shield. Yasuo Kato wiggled out of the turret and was struck by the fact that “complete silence prevailed on our ship.”

Then the thin sound of gurgling water and the distant rumble of explosions were broken by the strident notes of a bugle blaring “Abandon Ship!” Kato and his buddies started jumping into the water. As they hit the Surigao Strait, they heard a grinding clatter. Everyone looked up and saw Fuso’s bridge tilt “at an angle of 45 degrees to the left and [make] a terrible noise … it hit the water with a huge splash.”

With her bow submerged, Fuso was listing heavily to starboard. Suddenly she corkscrewed to port and upended. Kato, who had scrambled over the starboard rail, had found himself standing on the hull’s side and sliding along the blister. When Fuso spun to port he was flung into the sea on his back. He swam away.

Finally the old battleship rolled over and sank, spewing out unstable Borneo oil from her tanks, turning the sea into a gooey and deadly slime, trapping sailors. As the oil spread, it connected with flaming wreckage and started new fires. The hissing sound created by the fires reminded Ogawa of “roasting beans.” Sailors caught in the goo were killed in the inferno.

Fuso had sunk within 15 minutes of being torpedoed, between 3:40 and 3:50 am. She went to the bottom of Surigao Strait, taking most of her crew of 1,630 officers and men with her. Only a mere 10 members of the old battleship’s crew would survive. As Fuso departed the scene, so did Michishio, at about 3:38 am, sinking into the strait. Only four members of her crew survived.

“This Has to be Quick. Stand by Your Torpedoes.”

Incredibly, Nishimura plowed on with the courage of a samurai, joined by Shigure, Mogami, and the bowless Asagumo. So did Shima’s vessels, barely 40,000 yards behind Nishimura’s.

Hounded by McManes’s destroyers, Nishimura continued to steam north. The Japanese hurled shells at their tormentors, who used smokescreens with considerable effectiveness. On Mogami’s bridge, officers struggled to make sense of radar screens, trying to separate land masses from Japanese and American warships.

By now the opposing destroyers were in gun range, and Hutchins opened fire on Asagumo, hitting her and setting fire to the Japanese ship’s torpedo tubes.

On Louisville, Oldendorf watched the flashes of explosions and the beams of searchlights, awaiting the moment he could cut loose. From listening to the radio chatter, he determined he was up against two battleships, not four. The Japanese were now 26,900 yards away from his dreadnoughts. West Virginia led the parade of battleships, followed by Maryland, flagship Mississippi, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and California.

At 3:34 am, Destroyer Squadron 56 (Desron 56) Captain Roland Smoot on USS Newcomb led the next U.S. charge against Nishimura’s force, with nine destroyers maneuvering in three sections to corner the enemy. At 3:46, Captain Thomas Conley, commanding Smoot’s second section, signaled his destroyers, “This has to be quick. Stand by your torpedoes.” Smoot and Conley logically were worried that their tin cans would be at risk to both Japanese fire and American guns in this close-range encounter. Their attack would go in bare minutes before the American battleships would open fire.

18-Minutes of Vengeance

The Japanese kept closing in ragged formation. On the American dreadnoughts, radar operators and communicators chanted off steadily decreasing ranges. At 3:50 am, the range dropped to 15,600 yards. Oldendorf barked, “All right, give the order to open fire.”

TBS (Talk Between Ships) radios and soundpowered phones repeated the admiral’s order. On the battleships and cruisers—except Louisville, whose gunners cut loose before the order was given—buzzers sounded and gongs rang, and the battle line spewed forth massive shells with a titanic roar. Louisville’s deck and bulkheads rattled from the opening salvo.

The light cruisers fired their 6-inch guns rapidly, the heavy cruisers their 8-inch guns more deliberately. At 3:53 am, West Virginia opened fire on Yamashiro, 22,800 yards away, in full broadside. Her 16-inch guns, two gun turrets officered by men on their first sea voyage, exacted revenge for the Pearl Harbor humiliation by hitting Yamashiro on the first salvo. Yamashiro’s forecastle spouted flame, and her 14-inch gun turrets erupted with answering shells.

Two minutes later, California opened up with the first of 63 rounds of 14-inch shells. At 3:56, Tennessee joined the din—three American battleships that had survived Pearl Harbor blasting a single Japanese dreadnought.

On Mogami, the American barrage shone in distant flashes like light rows of a switchboard turning on one after another in a dark room. The light show was followed by the whistle and hiss of incoming shells. Those shells that missed sent up huge walls of white water. Those shells that hit Yamashiro impacted near her bridge, rocking the giant ship, starting fires, disabling the radar, but missing the compass and flag bridge.

Nishimura’s “T” had been fully crossed, but it did not matter. The previous hits to his ship had flooded the magazines for his No. 5 and No. 6 turrets, knocking them out of action, and he was about to unmask his No. 3 and No. 4 turrets. All of Mogami’s guns bore forward because of her wartime rebuildings, and Shigure’s primary weapons were her torpedoes. Furthermore, head-on targets were tougher to hit.

Under fire, poorly informed as to his situation, Nishimura radioed for Fuso to open fire on the Americans, unaware that his second battleship was sunk. Nor was Nishimura aware of Shima’s location behind him. The two Japanese forces would enter battle completely uncoordinated.

American shells rained down on Yamashiro. At 3:56, HMAS Shropshire finally had a firing solution and hurled 32 8-inch broadsides of eight guns at Yamashiro. At 3:59 am, Maryland located Yamashiro on her radar and ripped loose with her main battery.

The American heavy guns thundered for only 18 minutes, but it was time enough to avenge the humiliations of Pearl Harbor and Savo Island, raining destruction on Yamashiro. A direct hit exploded the officer’s wardroom, serving as a sickbay, killing medical lead Lieutenant Buntaro Kitamura and staff along with the wounded they were attending. Other heavy shells ripped open Yamashiro’s armor and shredded her superstructure.

A Sudden Promotion for Chief Petty Officer Yamamoto

While Yamashiro absorbed the shelling, Mogami, and Shigure struggled to fight. Mogami turned to port to unmask starboard torpedo tubes under heavy enemy fire.

The Americans did not ignore the cruiser. McManes’s destroyers spotted Mogami, illuminated by Yamashiro’s fires, bearing down on the onrushing Hutchins. The destroyers Daly and Bache opened fire on Mogami. On the cruiser, Captain Ryo Toma wondered if he was steaming toward Japanese or American ships in the confusion. To be sure, he flashed two large searchlights and a red Very star. The Americans answered his signals with a hail of shells.

Mogami took a hit on her mainmast, and the steel structure began to sag. Other shells blasted her two radio rooms and antiaircraft mounts. Toma decided to make a wide loop away to try to launch torpedoes from his port side. But the fire and smoke drew a fusillade of 6-inch and 8-inch shells from Oldendorf’s cruisers, which added to Mogami’s pain with hits on No. 3 turret, knocking it out of action, and another on the deck near the starboard after engine room’s air intake, which sent smoke into the engine room and forced the crew to evacuate.

On Mogami’s bridge, Toma and his officers argued over what they should do, continue the attack or withdraw? Toma wanted to withdraw, but his officers believed they could still fight their way past the Americans. Toma yielded to their Bushido spirit. Mogami turned around and headed north at 4 am.

At 4:02, two shells from Portland smashed Mogami’s compass bridge, and a third tore into the air defense center, killing almost all hands at both positions, including Toma. Only four signalmen who happened to be on the signaling platform were left alive and standing. Mogami was steaming along out of control, nobody in command.

Chief Petty Officer 1st Class Shuichi Yamamoto, the chief signalman, took the reins. He ran onto the smashed bridge and found the steering mechanism power had failed. He contacted the armored wheelhouse two decks below his feet on the sound-powered phone and called for manual steering and for someone to find the ranking senior officer.

Shuddering from repeated hits, Mogami swung out of line just as heavy shells slammed into the cruiser’s forward No. 1 engine room, sending high-pressure steam spewing in all directions, killing trapped engineers. Flames spread to the No. 9 boiler room, and choking black smoke poured out. Boiler tenders shut down the furnace.

At 4:03, another shell knocked out all lights in the port after engine room. Mogami had lost three engine rooms in as many minutes. The engineers in the port forward engine room ignored smoke and heat to provide Mogami with engine power. As the shaking cruiser rattled away, Lt. Cmdr. Giichiro Arai, the gunnery officer, was told he was in command. But with the ship’s guns firing, he could not report to the bridge. Yamamoto would have to keep the conn.

One Destroyer Against an Armada

Amid all this shellfire and destruction, the destroyer Shigure sailed on, straddled but not hit. There were so many near misses that the gyro compass was out. Her skipper, Commander Shigeru Nishino, barked requests into his radio to the other ships to find out where they were or whom he should shoot at.

On his bridge, Nishino summed up the situation rationally—one destroyer against an armada. At 4:03 am, he aborted his northward charge and started arcing a starboard reverse turn, heading south and out of the battle.

On Yamashiro, fires blazed from the dreadnought’s pagoda mast, looking like ceremonial lanterns back in Sasebo. The fires burned so brightly that the Americans could make out Yamashiro’s 6-inch turrets standing out against the glare of the flames. An American shell destroyed No. 3 turret and its two 14-inch guns in a violent explosion. The ship’s communications and two aft turrets were out. The only good news was that paymaster Ensign Yamauchi was standing guard over the emperor’s portrait in the conning tower.

Incredibly, Yamashiro fought on. The battleship made a wide, slow turn to unmask her 14-inch guns and hurled a broadside at the six American dreadnoughts. Japanese gunners continued to load and train turrets amid intense heat, smoke, and fires. Yamashiro traded shots with HMAS Shropshire with her main battery while firing secondary armament at the pesky destroyers.

At 4:01 am, the American battle line turned to starboard, and the dreadnoughts wheeled 150 degrees, heading back west across Surigao Strait. As the battleships turned, they were nearly parallel and steaming in the same direction as Yamashiro, broadside to broadside. Incredibly, as they made their turns, Tennessee and California started heading right at one another. Tennessee Captain John B. Heffernan fired off a series of orders and with deft ship handling avoided collision.

On California, Captain Henry P. Burnett realized what was happening and took his dreadnought out of line. The four battleships that had been shooting checked fire. Mississippi and Pennsylvania, unable to acquire radar locks, never fired a shot.

“All Ships Cease Firing”

Meanwhile, Oldendorf’s cruisers kept up the heat on Yamashiro. As they swapped salvoes, Desron 56, under Captain Roland Smoot, raced in at top speed to launch torpedoes. At 4:04 am, at a range of 6,200 yards, the American destroyers cut loose. The Japanese responded with a flurry of 6-inch shells. The Americans maneuvered to avoid the shells, which brought Albert W. Grant directly into Denver’s radar picture.

Denver mistook Grant for the Japanese Shigure, presumably racing in to fire torpedoes, and the American cruiser opened fire on Grant. Near misses scattered shrapnel. An American shell hit Grant’s fantail, knocking out the No. 5 5-inch turret. More shells from both sides punched into the forward stack and the forward boiler room, the forward engine room, the No. 1 40mm gun, the scullery room, and the port motor whaleboat. The lights, telephones, radios, and radars were blown out.

Grant’s skipper, Commander Terrell A. Nisewaner, reacted quickly. He fired off his five torpedoes at the enemy, then turned away. Simultaneously, Captain Smoot, in Newcomb, seeing the tragedy, shouted a TBS radio warning to Oldendorf, “You are firing on ComDesron 56! We are in the middle of the channel!”

Oldendorf got the message. At 4:09 am, he grabbed the voice radio on Louisville’s flag bridge and issued a blanket order, “All ships cease firing.” The American ships checked fire, and Newcomb came alongside Grant to tow away her damaged sister.

Aboard Grant chaos reigned—her lifeboats were wrecked, engines gone, the ship dead in the water at 4:20 am. She would have to be towed to safety. When the final tally was taken, it was determined that five Japanese and at least 11 American cruiser shells had impacted the destroyer. Six officers and 28 enlisted men lay dead. Ninety-four men were wounded.

Nishimura Goes Down With His Ship

The last shells and torpedoes flew at Yamashiro, scoring more hits. One of them—from the unlucky Grant—smashed the dreadnought’s starboard side at about 4:09, near the starboard engine room. The dreadnought slowed down then cranked back up to 12 knots at 4:09 am. On Yamashiro’s flag bridge, Nishimura told his chief of staff to report to Kurita: “We proceed to Leyte for the main attack. We will proceed until totally annihilated. I have definitely accomplished my mission as pre-arranged. Please rest assured.”

Now, with the firing ceased, Surigao Strait again reverted to blackness lit only by the raging fires on Yamashiro, Mogami, and Grant. The Japanese checked fire, too. Silence descended on the battlefield. Naval historian Samuel Eliot Morison wrote, “Admiral Nishimura and the officers and crew of Yamashiro must have regarded this cease-fire as God’s gift to the Emperor.”

Nishimura decided to meet Shima’s force and regroup. The blazing battleship commenced a wide turn to port, heading southwest.

On the American ships, everybody stared down at the radar plots, separating out the various blips. As the Japanese dreadnought retreated, the Americans figured out which one was Yamashiro. For the last time in the history of warfare, a battleship fired its ordnance at another such vessel, as the flagship Mississippi unleashed her first and only broadside of the night, doing so at Yamashiro at a range of 19,790 yards.

With the American battle line in some disorder and the Japanese apparently retreating, Oldendorf turned the pursuit over to his cruisers and destroyers, ordering them to resume fire at 4:19 am. Before they could comply, the fattest pip on the American radar screens abruptly vanished. It seemed that Yamashiro had sunk, probably by capsizing, according to the later Naval War College report.

The War College was right. Four torpedoes hit Yamashiro, possibly from Newcomb, and the stricken battleship went dead in the water, keeling over to port. Fires amidships silhouetted the pagoda superstructure in a lurid glow as it heeled over like a collapsing sand castle.

On the bridge, the skipper, Rear Admiral Katsukiyo Shinoda, calmly passed the word to abandon ship. He and Nishimura remained on their bridges. Within two to five minutes, the blazing dreadnought keeled over and capsized.

Nishimura, his staff of 20 officers, Shinoda, and nearly all of Yamashiro’s crew of 1,636 officers and men went to the bottom of Surigao Strait. While a large number of sailors survived the sinking, only two warrant officers and eight petty officers returned to Japan, the same number as from Fuso.

The Last Japanese Torpedo Salvo

Shigure and Mogami were now the only vessels of Nishimura’s force left afloat, and both were withdrawing. Shigure took an 8-inch shell in her fantail, and her skipper logged “decided to retire.” The battered cruiser and destroyer headed south, and at 4:15 their lookouts were astonished to see a destroyer racing toward them at 30 knots. It was Shima’s lead ship, the Shiranuhi. Behind her was Shima’s flagship, Nachi, starting the next phase of the battle.

Shima’s ships had gone through an interesting journey, passing by raging oil fires and wreckage belonging to Nishimura’s shattered vessels, hearing and seeing gunfire to the north. They advanced through smoke screens. Oil fires blazed on the ocean. The ships passed by the badly damaged and helpless Asagumo. Then radar spotted two contacts dead ahead, at 4:15 am. Figuring it was the enemy, Shima ordered, “All ships attack!”

Shima’s four destroyers and two cruisers dashed forward, unmasked their torpedo batteries, and fired their Long Lance torpedoes, which had caused so much havoc in the grueling struggles for Guadalcanal. The torpedoes had eight miles to run.

As it happened, their target was Oldendorf’s flagship Louisville. But the torpedoes missed. Shima and his men peered into the smoke and mist to observe results—and out of the smoke came Mogami, her No. 3 gun turret a ruin, barrels blackened, forecastle riddled with holes, flames smoldering from her flight deck aft.

With Chief Petty Officer Yamamoto still on the bridge, the blasted Mogami was retiring at last. Crewmen on Nachi howled banzais of encouragement as the two ships closed the range. On Nachi’s bridge, Captain Enpei Kanooka thought that he would pass Mogami a little too close, figuring that Mogami was dead in the water. But to everyone’s amazement, Mogami was actually steaming along—just barely—and right for Nachi.

Kanooka shouted “Full reverse!” and right rudder to avoid Nachi’s sister. Too late. At 4:23, Nachi’s anchor deck converged with Mogami’s starboard at No. 1 turret, and the two ships collided with a sickening, jarring crunch. The collision added more dents to Mogami’s battered hide, wrecked Nachi’s No. 2 antiaircraft mount, and ripped a 15-meter gash in Nachi’s port bow at the waterline. Flooding alarms went off, and the two cruisers pulled themselves apart.

On Mogami’s bridge, Yamamoto bawled through a megaphone, “This is Mogami! Captain and XO killed! Gunnery officer in charge. Steering destroyed. Steering by engine. Sorry!”

Shima and Kanooka, exasperated, accepted the blame. Nachi began crawling southward at five knots. Mogami struggled to get in line behind her two sisters. Everyone listened for explosions from the 16 torpedoes fired, but there was no sound.

While Shima’s cruisers maneuvered in clumsy fashion, her destroyers tried to attack, torpedo tubes ready. There was no American gunfire to track—Grant’s mishap had silenced Oldendorf’s guns.

At 4:35, Shima signaled his destroyers, “Reverse course to the south and rejoin.” The irritated destroyer skippers did so, pulling out of American range.

A Fighting Retreat

On Nachi, Shima was assessing the situation. His flagship was damaged from the collision but could still do 18 knots. But it was clear disaster already reigned, as exemplified by the battered Mogami. Shima and his officers conferred. Torpedo officer Kokichi Mori said to Shima, “Admiral, up ahead the enemy must be waiting for us with open arms. Nishimura’s force is almost totally destroyed. It is obvious that we will fall into a trap. We may die anytime. In any case, it is foolish to go ahead now.” Shima got the point. Time to withdraw.

On Louisville, Oldendorf studied the smoke, oil fires, and silence through his binoculars and ordered a cautious pursuit of his beaten enemy. He had no idea if there were more enemy ships out there—intelligence suggested there might be as many as three battleships, five cruisers, and six to eight destroyers beyond the smoke—ready to ambush him with shells and Long Lance torpedoes. And his battle line was increasingly short on ammunition. At 4:37 am, Louisville, Portland, Minneapolis, Denver, and Columbia headed south.

At 4:41, Shima ordered his ships to follow behind Nachi. Hobbling along at 20 knots, they were retreating at a slow speed. On the battered Mogami, ammunition started cooking off, hampering repairs and endangering the crew. Arai ordered his men to jettison torpedoes to prevent them from exploding, but four of them exploded, adding to the smoldering fires. Incredibly, the engines kept turning, and Arai used hand steering to maneuver his ship.

The battle still sputtered on. As the Japanese ships retreated, they met up with the PT boats that had not expended their torpedoes earlier in the struggle. Lieutenant Carl T. Gleason’s Section 11, consisting of three PT boats, attacked the destroyers Shigure and Asagumo. The Japanese fire was ragged and off target, but one American torpedo detonated prematurely. Another slithered out of its tube on PT-326 and clattered to the deck, a defective “hot run.” The blazing fish provided the Japanese with a target, and the Japanese hurled 5-inch shells at the PT boats. Shrapnel injured one man before the burning torpedo could be rolled overboard.

The Japanese ships continued to withdraw, now hooking up with the Abukuma, which had repaired its damage and was ready to attack. Shima declined the offer but was happy to add another escort to his damaged force.

Oldendorf’s Pursuit Called Off

By 5:20 am, Louisville was eight miles west of Esconchada Point, where Nachi and Mogami had collided an hour earlier. Oldendorf studied the scene through his binoculars and told his column to turn right and prepare to shell the fleeing Japanese with full broadsides. The open fire gongs rang at 5:29, and the Americans hurled more shells at the Mogami, scoring several direct hits. Yet the cruiser survived this latest bombardment, cranking up to 14 knots.

Other American shells rained down from Minneapolis on Asagumo, starting a fire, holing her oil tanks. Barely able to make seven knots, the destroyer was on fire, spreading and menacing its torpedoes. At 6 am, Asagumo’s skipper, Commander Kazuo Shibayama, ordered his men to abandon ship.

Worried about Japanese torpedoes, Oldendorf ceased fire at 5:39 am and swung back north. Now the American destroyers began nosing into the wreckage in the growing dawn to pursue survivors of the two battleships and two destroyers sunk in Surigao Strait. Oldendorf ordered his ships, “Do not overload your ships with survivors. Search each man well to see that he does not have any weapons. Anyone offering resistance—shoot him. Proceed independently to pick up survivors.”

By now Shima’s weary collection of ships was heading out of Surigao Strait into the Mindanao Sea, enduring further brushes with PT boats. First up was PT-491, which charged Mogami, firing torpedoes. Mogami hit back with 8-inch shells, and PT-491 retreated.

Back in Surigao Strait, American destroyers slowly steamed into debris-strewn waters filled with Japanese survivors who refused American entreaties to surrender. Other ships pursued the crippled Asagumo, whose bows had been torn open. PT-323 hurled a torpedo into the immobile tin can, throwing men on her weather decks into the water. Hearing word of this target, Oldendorf sent in the cruisers Denver and Columbia and six destroyers to polish off Asagumo.

Oldendorf was beginning to receive frantic messages from his bosses at 7th Fleet—Kurita’s battleships had steamed through the unguarded San Bernardino Strait and were bearing down on the poorly defended escort carriers off Samar. The fox was among the chickens, and Oldendorf had to steam to the rescue, despite his shortages of ammunition. Nishimura had succeeded in one thing—drawing off Kinkaid’s heavy warships to expend ammunition and energy against the attack from the south instead of Kurita’s thrust from the north.

Attacked from the Air

Meanwhile, Shima’s retreating ships, heading home in the early morning, awaited the one certainty of the day—American air attack. Shima radioed for fighter cover but instead received an attack of nine Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bombers and four Grumman F6F Hellcat fighters from the escort carrier USS Santee and two Avengers and six Hellcats from USS Sangamon, launched at 5:45 am. They pounced on Shima’s battered vessels and incorrectly reported them as two battleships. That happened often. Japanese heavy cruisers had massive superstructures and looked like battleships to airmen. The Americans swooped in to attack. Strafing killed nine and wounded 25 on Shiranuhi, and the luckless Mogami took yet another torpedo hit.

Ten Avengers and five Grumman FM-2 Wildcats from USS Ommaney Bay’s VC-75 came next, storming down on the smoking Mogami, scoring two more hits, starting fires, and bringing the ship to a halt. The destroyer Akebono sprayed hoses on the cruiser. Everyone but the antiaircraft crews fought the fires.

The American bombs smashed into the cruiser’s oil tanks, setting them ablaze. Gunnery officer and acting commander Arai ordered the three forward 8-inch magazines flooded to prevent an explosion. But the warped bulkheads meant that the valves for the No. 1 gun room would not open. The cruiser was blazing and could sink at any moment.

In tears, Arai ordered his men to abandon ship at 10:30 am. With her davits broken, Mogami could not use her cutter, so Akebono closed Mogami’s port quarter to take aboard the cruiser’s crew.

At 9:33 am, Shima faced his last attack of the day: 13 Curtiss SB2C Helldiver dive bombers, which strafed the Japanese ships, punching holes in the destroyer Ushio.

On Mogami, the exhausted crew mustered topside on weather decks to abandon ship after three hours of desperate fire fighting, shuffling aboard Akebono. At 12:56, Akebono fired a Long Lance into Mogami’s port side, and the cruiser began to sink, her demise hastened by an explosion in No. 1 magazine. At 1:07, as her crew stood by on Akebono watching and crying, Mogami slipped beneath the waves. All but 20 officers, 171 enlisted men, and one civilian of Mogami’s 850-man crew were saved by Akebono.

At 1:33, Shima got more bad news—a message from Kurita that the main force was canceling its planned attack on the Leyte anchorage and was retreating, having failed in its mission. Shima’s reaction is unrecorded, but he continued his retreat.

Shigure headed for Brunei and ultimate safety in Japan. But when Shigure tied up at Sasebo on November 14, her skipper, Nishino, faced relief of command at the end of the month, accused of lack of aggressiveness in Surigao Strait.

The fallout continued. Abukuma was caught a day later, on October 26, by U.S. Army Air Forces Consolidated B-24 Liberators of the 33rd Squadron, which hammered her. Japanese antiaircraft gunners knocked down three B-24s, but flames spread across Abukuma’s decks, igniting torpedoes. Her skipper, Captain Takuo Hanada, ordered the ship abandoned. He and 25 officers and 257 enlisted men of her 438-man crew survived.

One of the Most One-Sided Naval Actions in History

What had happened was simple enough. Nishimura and Shima had steamed into a gauntlet of gunfire and had been defeated in one of the most one-sided naval actions in history. The Japanese could not count their dead, but they numbered in the thousands, including Nishimura. Two battleships, a heavy cruiser, and three destroyers were lost in the action, and the light cruiser Abukuma was lost shortly after. The Americans lost exactly 39 killed and 114 wounded, most of them on Albert W. Grant due to friendly fire, and a single PT boat.

More importantly, the southern portion of the Japanese plan to smash the American invasion fleet with a double pincer movement had failed completely. The northern pincer nearly defeated a much weaker American force off Samar, mostly due to Vice Admiral Halsey’s controversial decision to leave the San Bernardino Strait unguarded. But Oldendorf’s cool, meticulous planning and courageous men had crushed the southern pincer.

Why the Japanese attack failed was even easier to answer. The Japanese underestimated American power and resilience, as they had all through the war, and overestimated their own resolve. Bushido code was not enough against American technology and determination. Japanese gunnery and torpedo efficiency was far below the glorious standards of 1942. Even Japanese seamanship, as evidenced by the collision of Nachi and Mogami, was faulty. Nishimura and Shima did not coordinate their forces—they did not even seem to know where their own ships were. Probably the single most intelligent Japanese decision in the entire battle was Shima’s—to withdraw.

The surviving Japanese blamed their late boss, Nishimura. Hiroshi Tanaka of Yamashiro described survivors as saying that Nishimura’s strategy was that of a warrant officer, not an admiral.

Still, it was difficult to see what else Nishimura could have done. His orders were clear and specific—steam into Surigao Strait, punch through the American defenses, and savage the American transports. He had tried to do so with every ship at his command and fiber of his being, paying the price with his own life. The very cause was hopeless, but Nishimura and his sailors did their best to carry out their orders with full and hopeless valor.

The End of the Battle Line Era

It was also the end for a style of warfare that dated back to 1655, when Britain’s Duke of York defeated the Dutch Admiral Obdam in the Battle of Lowestoft … the battle line. It had translated from the age of sail to that of steam.

Now the battle line had been rendered obsolete by the development of air power, the brawling night surface actions of Guadalcanal, and the unsporting but deadly submarine. The even more deadly power of guided missiles and atomic weaponry were yet to come.

Such thoughts probably did not occur to the victorious American sailors as the sun rose over the smoking wreckage, fuming muzzles, and oil fires in Surigao Strait. Aboard Louisville, Oldendorf assessed the desperate messages from Samar and ordered his officers to start plotting courses and formations to support the endangered escort carriers.

On the American battleships, the young sailors marveled that despite a night of sound and fury their battleships had suffered nothing. They were all alive to greet the new day. The loudspeakers blared, “Now hear this. Secure from general quarters. Set torpedo defense watch.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments