By Bob Kunzinger

Georgina’s mother sat next to me at her dining room table. She and her husband were veterans of the Great Patriotic War, and back in 1996 we all sat about the table on Victory Day and talked about the siege.

The old woman grasped my arm and talked in Russian while her husband listened. They both wore medals, one of his for “extreme bravery.” It was, of course, May 9, and everyone was in a jovial mood. The day was light and airy, and it reminded me of holiday dinners at home, or Fourth of July barbeques. It reminded me of any occasion where we celebrate, albeit with a certain twist. At home and in Europe we celebrate victories; on this day, citizens of St. Petersburg celebrate survival. There is a difference.

In Europe, of course, Victory Day is May 8, but because of the time difference and the surrender not being signed until nearly midnight in Germany, the defenders of Leningrad did not find out until the next day, May 9.

A Job for Everyone

The small room was crowded. This was, for all intents and purposes, the apartment of two citizens of the Soviet Union, two comrades during the war whose daughter married a Soviet naval captain who manned a ship in the Arctic with the mission of seeking out American submarines. These were the people I was raised to fear and despise. We drank wine and ate a small dish of onions. Soup would be next, and salmon.

Communism had ended a few short years earlier. Georgina’s mother kept hold of my arm and spoke slowly while her husband poured me more to drink. He was a big man with a wide, tender smile. And she might have been my own grandmother, whose eldest son fought in the war.

“My job was in a munitions factory,” she told me. Everyone had a job. Lt. Gen. Markian Popov was the officer in charge of Leningrad during the siege, and at the beginning of the war he made a statement for the citizens of the city: “The moment has come to put your Bolshevik qualities to work, to get ready to defend Leningrad without wasting words. We have to see that nobody is just an onlooker and carry out in the least possible time the same kind of mobilization of the workers that was done in 1918 and 1919. The enemy is at the gate. It is a question of life and death.”

Everyone had a job to do.

The Leningrad “Blokada”

The Soviet involvement in the Great Patriotic War, as they refer to World War II, actually began on June 22, 1941, when the German Army’s three million troops invaded the Soviet Union, almost two years after World War II started for the rest of Europe with Hitler’s invasion of Poland. Soviet Premier Josef Stalin had been a willing accomplice in that invasion with the Red Army invading Poland from the east. Stalin did not believe that Hitler would turn on the Soviet Union.

Following the Nazi invasion, Hitler had unintentional help in the Soviet Union since Stalin never really cared about casualties. Early in the war Stalin ordered the Red Army to remain firm as the Germans captured nearly six million prisoners of war, most of whom died in captivity. In fact, Stalin was so adamant that troops hold their positions that he ordered the execution of frontline commanders who retreated. By 1942, more than 77,000 Soviet citizens had been executed for supposed cowardice and treachery.

Two decrees were issued: Order 270 made it a criminal offense for any soldier to surrender and Order 227 declared that any commander retreating without permission would be tried before a military tribunal. These became known as the “Not a Step Backward” decrees. The military overseers dug trenches behind the armies and filled them with sharpshooters. Later estimates put the total number of Soviet dead in World War II at 20 million, but the most accurate estimate in retrospect is about 32 million Soviet military and civilian deaths, roughly the present population of Canada.

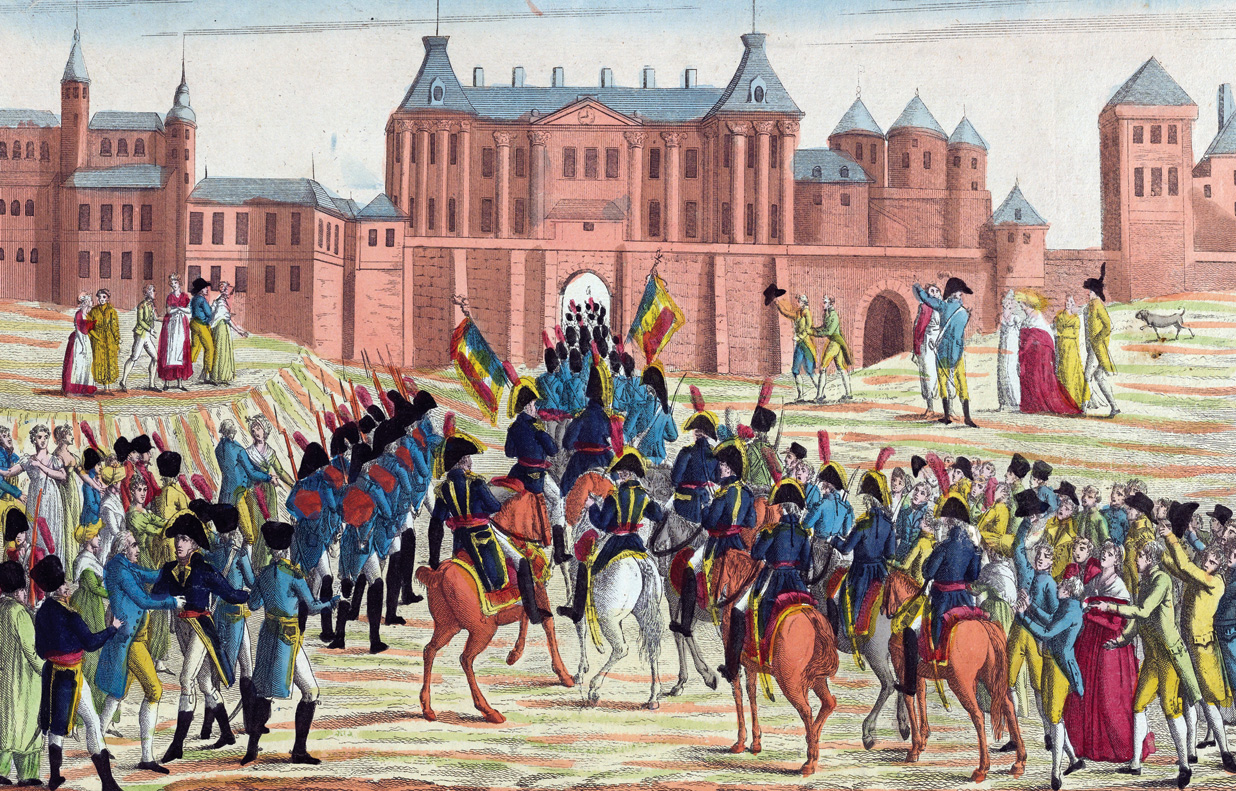

In Leningrad, however, the vast majority of casualties were not soldiers, but women and children. One Victory Day I walked alone through town after the veterans’ parade. I passed 14 Nevsky Prospect, where residents leave flowers beneath a sign in place since the war, which reads, “Citizens! During artillery shelling this side of the street is most dangerous!” At the Piskaryovskoye Cemetery, too, tens of thousands of mourners leave flowers on one of the 186 mounds of mass graves or at the monument of the Motherland, a statue of a woman lamenting those who died during what the rest of the world calls the “siege,” but which Russians call “Blokada,” the blockade.

200,000 Deaths from the Cold

The siege of Leningrad is political and military history, yet it is also personal. It is the story of the general making tough decisions, his frame a sliver of what it had been before the war; it is the story of the child living on a few grams of bread, his mother making sure he only takes small bites throughout the day for fear if he eats it all at once he will surely starve to death.

The siege is one of the chapters in books about 20th-century atrocities; yet it is also the conversation over beers in a corner pub, where most veterans still hold back their emotions against the questions of the curious. Some allow others to cross the line into their world, allow them to suffer the starvation through stories and tears because they know it might be the only way these great heroes, the defenders of Leningrad, will be remembered.

One woman at Palace Square spoke to me of her worst memory. She was 15 during the siege when she had to pull a sleigh carrying the body of her sister, who had died of starvation. She made it to the graveyard and left her sister on the pile of bodies. Another there, Alexander, remembered how he would cut up a piece of bread once a day for his brothers. His parents had died of starvation some time earlier.

Nearly three million civilians, including nearly half a million children, refused to surrender despite having to deal with extreme hardships in the encircled city. Food and fuel would last only about two months after the siege began on September 8, 1941, and by winter there was no heating, no water, almost no electricity, and little sustenance. These citizens still had two more years of this to endure. Leningrad is roughly at the same latitude as Anchorage, Alaska. It gets cold.

During that first January and February, 200,000 people died of cold and starvation. Because disease was a problem, the bodies were carried to various locations in the city, most notably what became the Piskaryovskoye Cemetery. Even so, people continued to work in the deplorable conditions to keep the war industries operating. When they were not working or looking for food and water, they were carrying the dead, dragging bodies on children’s sleighs or pulling them through the snow by their wrists to the cemetery.

One man said, “To take someone who has died to the cemetery is an affair of so much labor that it exhausts the last strength in the survivors. The living, having fulfilled their duty to the dead, are themselves brought to the brink of death.”

But the people of Leningrad would not surrender; they always heeded Popov’s decree. Still, after the war, Stalin ordered the general’s arrest for not communicating with Moscow often enough, and he was sent to a gulag.

Doroga Zhinzni: The Road to Life

I met a woman named Sophia in a graveyard on the north side of the city. She had been an adolescent during the reign of Czar Nicholas II and lost her husband and son during the siege. We sat on a bench, and she told me of her life, of her family, as if time had turned it into a hazy event she had heard someone tell about years earlier. Her hands were transparent, and she spoke of Leningrad as being a prisoner of war, with no rations and no electricity and little hope. The city became a concentration camp, its citizens condemned to death by Hitler.

Thousands of people were evacuated across Lake Ladoga via the famous frozen “Doroga Zhinzni,” the “Road of Life.” During warm weather, some were boated across, but in winter they were carried on trucks across the frozen lake under German fire. Heading north was pointless. The Finnish Army, allied with the Germans since the bitter Winter War with the Soviets in 1939-1940, held the line there.

Meanwhile, in Leningrad, workers took all the treasures from the Hermitage Museum and the Palaces of Peterhof and Pushkin and buried them in basements and beneath St. Isaac’s Cathedral. Not everything made it out, including many paintings and the mysterious amber room of the Summer Palace. On Hitler’s orders most of the palaces, such as Gachina, the Summer Palace in Pushkin, and other historic landmarks located outside the city’s defensive perimeter, were looted and then destroyed, with many art collections being transported to Nazi Germany.

The Leningrad airport and many factories, schools, hospitals, transport facilities, and other buildings were destroyed by air raids and long-range artillery during the 30-month siege. Still, students continued their studies and some even graduated, celebrating between bombings.

Then, composer Dmitri Shostakovich wrote his Seventh Symphony, the Leningrad Symphony, and it was performed in this besieged city, bombs exploding in the background, but no one leaving the performance. To hear the symphony today in the cemetery while thousands of people walk about without talking is to understand how music can capture emotions more readily than words.

The Seventh played while my friend, Mike Kweder, and I walked about in the silence of the mourners, and we stopped at times to talk, to wonder. Mike asked if I thought the cemetery would continue to be a destination on Victory Day, or any day, after the veterans were all gone; he wondered when the day would be taken for granted.

“We Simply Had Nothing to Eat”

When I first came to St. Petersburg, the veterans numbered in the thousands. Now there are only a few thousand, and many of them are not well. Back in the early 1990s one could not wander more than a few feet without meeting a survivor of the siege. Today, we must look intently for the medals, or for old women on benches, holding flowers. Then we both saw a young couple walk by with their young son playing with a toy rifle, making mock shooting noises, and I hoped he did not point the plastic toward someone who had seen enough.

For the Soviets during the war, the future of their country and perhaps victory or defeat in World War II were in the balance. When the initial attack on Leningrad failed, Hitler ordered the siege to free up troops the Nazis needed elsewhere. Had the Germans taken Leningrad or destroyed it faster, they would have been able to sweep attack Moscow, the Soviet capital and their real goal, from behind.

The troops protecting the city were reliant upon its citizens to supply them with food and munitions—not an easy task for a city with virtually nothing.

“We simply had nothing to eat,” one woman told me on a bench in the village of Pushkin. I had been walking about the town and stopped to buy some doilies she made by hand. She also had a plate of poppy seed buns her granddaughter had baked. The siege, she said, was a time during which one gauged success by being alive or not.

“I thought about food at breakfast, I played with it at lunch, and I pretended to consume it at dinner,” she said. “This went on for me nearly from the start.” She took a bite of one of the poppy seed rolls and looked around for other people who might buy her knitting. “Really, we were hungry from the very start. People must know that.”

When the Nazis took Schliesselburg east of Leningrad, the city was officially surrounded, and within three years half of the city’s population would be dead. Despite the danger, factories continued to supply arms and ammunition. Old men, women, and children replaced workers who left for the battlefield.

“But here’s what mattered: the city tried to act like a city,” Georgina’s mother told me as she let go of my arm and ate cake, sipping tea and pausing to recall details. “A few dozen schools continued to educate, 20 movie and playhouses stayed open, the Grand Philharmonic played for at least a year.”

Some survivors, however, tell of wartime NKVD activities, or encounters with people who had such severe mental illness from disease and starvation that it had became unbearable. The accounts are sometimes spurious, but too many narratives contain too many parallel events to write them off as exaggerated. Several wrote of what became known as “blockade cannibalism,” including the story of a boy who was enticed to enter someone’s apartment to eat warm cereal only to discover a room of butchered corpses behind a door.

Radio broadcasts continued. The survivors of the siege declare that efforts to maintain morale were as significant as the troops on the front lines in saving the city.

Exterminator Squads

A few years ago at Rasputin’s, a pub just outside the Nevksy Monastery, I met an elderly man. I immediately recognized him from earlier in the week at Trinity Cathedral, where we both lit candles at the tomb of Saint Alexander Nevsky, patron to soldiers and young men. I knew the man from his long gray hair and worn boots. I was drinking wine and waiting for soup when he asked me if he had seen me earlier in the week.

We talked, and I asked if he was a veteran. He smiled and said yes, and eventually he told me of his covert operations behind enemy lines, deep in the German-occupied sections of the city. He was on food detail, he told me, pointing to his own meal. He and his comrades were in charge of transporting as much food as possible into the city. He had no reason to fabricate the story, yet I had never heard of such maneuvers. We drank together, and I told him of Americans I had known who fought in the war.

I have met many Russians in pubs who love to fabricate stories of heroism, but this man was not among them. According to the curator at the Monument to the Heroic Defenders of Leningrad, for a few months in the summer of 1941 Soviet guerrilla detachments called “exterminator squads” set up camp behind enemy lines to assist regular troops and volunteers defending the city. They annoyed the Nazi commanders to no end.

One “guerrilla province” was formed in Nazi-controlled areas of Leningrad—something unheard of in much of military history—a vast area behind enemy lines under its own political and economic rule. Thirty-five thousand troops operated there, harassing the Nazis. They also managed to transport more than 500 tons of food to the city in March 1942. The old man showed me the medal he was awarded for “extreme bravery.”

“I Shaved Every Day”

I met another nearly 90-year-old man on the steps near the Motherland statue. A young girl of about eight reached up to hand him a flower. and he cried. I said how beautiful it was that parents still teach their children to respect him and his comrades 60 years or more later. He smiled and added that what touched him was when he was a young man leaving for the front lines, a young girl had run to him and handed him a flower. This young girl reminded him of that moment.

“It happens every time a child gives me a flower,” he said. He laid the flower at the foot of the statue. I asked what had gotten him through the worst of the days, when, truly, it seemed there was no hope of continuing. He stroked his beard.

“I shaved every day,” he said. “No matter how weak we were, and no matter how long we might spend doing nothing but waking, resting, sleeping, and waking again, every day we were encouraged to shave, and did. It made me feel like I was ready for what was next.”

Leningrad’s Astoria Hotel did not resemble a hotel at all during the siege. It was a hospital with bodies in the hallways and on the stairs. The manager at the time, Anna Andreievna, spoke of how the ground was too frozen to bury the dead, so the bodies accumulated in the streets. But the survivors never lost faith in the Red Army, in the workers, in themselves, and in God.

“I used canes to walk to and from the hotel,” Anna remembered. “I was so weak, dropping from 160 pounds to about 90. But the ones who stopped, died. Sometimes I would pass someone breathing heavily in the morning sitting on a step, and in the afternoon pass again and that person would be dead.”

The Eternal Memory of the Siege of Leningrad

Leningrad’s population of dogs, cats, horses, rats, and crows disappeared as they became the main courses on many dinner tables. Nothing was off limits, and stories circulate about eating dirt, paper, and wood. One void with stories of the siege lies in the details left out or destroyed. Stalin censored much of the news of anything except heroism.

The people of Leningrad ate wood glue, the paste from the back of wallpaper, and boiled leather belts. People ate the buds on the low branches in spring; everyone who survived the siege can recall “pigweed.” One woman used one of her dead children to feed the others.

For nearly three years, Leningrad was under attack night and day, and almost half its population, including 700,000 women and children, perished. The Germans left the city of Peter the Great, his “Window to the West,” in ruins. Still, they could not defeat Leningrad.

The great siege and the sacrifice of the people who suffered and died will always be remembered—even as the number of survivors continues to dwindle.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments