By Joseph Frantiska Jr.

Throughout the history of warfare, there have been targets that have been notably reluctant to fall. One such highly resistant target was the Thanh Hoa Railroad and Highway Bridge spanning the Song Ma River three miles northeast of Thanh Hoa, the capital of Annam Province in North Vietnam. The Vietnamese gave it the nickname Ham Rong, or “Dragon’s Jaw,” since the terrain in the immediate area is flat with the exception of a jagged ridge to the west known as Rong Mountain and a small hill to the east known as Ngoc (Jade) Hill. Together, the two promontories figuratively form the jawbones of a dragon’s mouth on either side of the river.

Between 1965 and 1972, during the Vietnam War, the bridge was the objective of many unsuccessful attacks by United States Air Force and Navy aircraft. Designed by Nguyen Dinh Doan and originally built by the French during the colonial era in Vietnam, the Thanh Hoa Bridge was destroyed in 1945 by Viet Minh guerrillas when they ran two TNT-laden locomotives together at the midpoint of the bridge. The North Vietnamese began to rebuild the bridge in 1957. It was completed in 1964 with a span of 540 feet, a width of 56 feet, and a height of 50 feet. Ho Chi Minh himself attended the dedication.

The rebuilt bridge had two steel truss spans that rested in the center on a gigantic reinforced concrete pier 16 feet in diameter, with concrete abutments at each end. Hills on both sides of the river provided solid bracing for the structure. Between 1965 and 1972, eight concrete piers were added near each end to give the bridge additional resistance to bomb damage. A one-meter-gage railway track ran down the 12-foot-wide center of the bridge, which had 22-foot-wide concrete highways on either side. The structure would prove to be one of the most challenging targets for American airpower during the war.

The First Day of Bombing

With the beginning of Operation Rolling Thunder, the American bombing campaign against strategic targets in North Vietnam, the Thanh Hoa Bridge became a primary target for U.S. forces. Realizing the importance of the bridge, the Vietnamese had set up a brutal network of five air defense regiments in the area. They typically used SA-2 surface-to-air missiles (SAMs). Because of their large 35-foot size, the missiles were referred to as “flying telephone poles.”

The first and largest strike against the bridge was led on April 3, 1965, by Lt. Col. James Robinson “Robbie” Risner. It comprised 79 aircraft, including 46 F-105 Thunderchiefs armed with AGM-12 Bullpup air-to-ground missiles as the main strike force, 21 F-100 Super Sabres serving as fighter escorts, two RF-101 Voodoos for reconnaissance, and 10 KC-130 tanker aircraft. The Bullpup was roll-stabilized and visually guided by the pilot or weapons operator using a tracer flare on the rear of the missile to track the weapon in flight while using a control joystick to steer it toward the target using radio signals. It was initially powered by a solid-fuel rocket motor and carried a 250-pound warhead.

Shortly after noon on the day of the strike, aircraft of Rolling Thunder Mission 9-Alpha climbed into the Southeast Asia skies on their approach to the Thanh Hoa Bridge. The sun glinting through the haze made the target difficult to acquire, but Risner led the way “down the chute,” and soon missiles began exploding on the target. Since only one Bullpup could be fired at a time, each pilot had to make two firing passes. On Risner’s second pass, his aircraft was hit just as his Bullpup struck the bridge. With blinding smoke in his cockpit and his aircraft leaking fuel like a sieve, Risner somehow coaxed his damaged aircraft back to Da Nang.

Captain Bill Meyerholt was in the third flight. As he pushed his Thunderchief into a dive and fired a Bullpup, the missile streaked toward the bridge. When the smoke cleared, Meyerholt was shocked to see no visible damage to the bridge. The Bullpups had merely charred the heavy steel-and-concrete structure. The remaining missile attacks confirmed that firing Bullpups at the Dragon was about as effective as shooting BBs at a battleship.

The bombers came in for their attack, only to see their payloads drift to the far bank because of a strong crosswind. Major George C. Smith’s F-100D was shot down near the target point as he performed his flak-suppression mission. Antiaircraft resistance was much stronger than anticipated. No radio contact could be made with Smith, and he was officially listed as missing in action (MIA). No further word was ever heard of him.

Pilots in the last flight of the day, led by Captain Carlyle S. “Smitty” Harris, adjusted their aim points to allow for the crosswind and scored several hits on the roadway and superstructure. Harris tried to assess bomb damage but could not do so because of smoke obscuring the target. The smoke would be an ominous warning of things to come.

One pilot destined to become a prisoner of the North Vietnamese was Lt. Cmdr. Raymond A. Vohden, who was passing just north of the bridge when his Douglas A-4C Skyhawk was shot down. Vohden was captured and held in various POW camps in and near Hanoi until his release in February 1973. An RF-101C piloted by Captain Herschel S. Morgan was hit and went down some 75 miles southwest of the target area, seriously injuring Morgan, who was also captured and held around Hanoi until his release the same month as Vohden.

When the smoke finally cleared, observer aircraft found the bridge still standing. Thirty-two Bullpups and 120 750-pound bombs had been aimed at the bridge. Numerous hits had charred every part of the structure, yet it showed no sign of going down. Another strike was ordered for the next day.

MiGs on the Second Flight

On the second day of bombing, Harris was flying under call sign “Steel 3.” He took the lead and oriented himself for his run on a 300-degree heading. He reported that his bombs had hit the target on the eastern end of the bridge. Steel 3 caught fire as soon as he left the target. Radio contact was garbled, and other members of the flight watched helplessly as Harris’s aircraft, emitting a 20-foot-long trail of flame, headed due west of the target. Flight members had him in sight until the fire died out, but no one observed a parachute or saw the aircraft impact the ground. Harris’s aircraft had been hit by a MiG whose pilot later recounted the incident in the Vietnam Courier on April 15, 1965. It was not until much later that the Air Force would learn that Harris had been captured and held prisoner for eight years before being released in 1973. Fellow POWs credited Harris with introducing the “tap code” that enabled them to communicate with each other inside their prison cells.

MiGs had been seen on previous missions, but this was the first time in the war that the Russian-made planes had attacked American aircraft. “Zinc 2,” a Republic F-105D flown by Captain James A. Magnusson, had its flight bounced by MiG 17s. As Magnusson was breaking to shake a MiG on his tail, Zinc 2 was hit and he radioed that he was heading for the Gulf of Tonkin if he could maintain control of his aircraft. Magnusson’s aircraft finally ditched over the gulf near the island of Hon Me, and he was not seen or heard from again. He too was listed MIA.

One of the pilots’ guardian angels was Captain Walter F. Draeger, whose Douglas A-1H Skyraider was also shot down over the Gulf of Tonkin just northeast of the Dragon that day. Draeger was providing air cover for downed American pilots and rescue helicopters when he was struck by enemy ground fire. His aircraft was seen to crash in flames, but no parachute was observed. Draeger was listed as MIA. For his actions that day, Draeger earned the Air Force Cross. The remaining aircraft returned to their bases, discouraged. Although over 300 bombs had scored hits on the second strike, the bridge still stood.

19 Pilots Shot Down

From April to September 1965, 19 more American pilots were shot down in the general vicinity of the Dragon’s Jaw, including many who were captured and later released: Howie Rutledge, Gerald Coffee, Paul Galanti, Jeremiah Denton, Bill Tschudy, and James Stockdale. On September 16, 1965, Risner’s F-105D was shot down a few miles north of the bridge. As he landed, Risner injured his knee, which contributed to his ultimate capture. Risner was held in Hanoi until his release in 1973, spending 41/2 years in solitary confinement.

The Bullpup missile had too small a warhead to inflict any damage on the bridge. In addition to the lack of punch, the Bullpup also exposed the pilot to extreme danger as this was not a “fire and forget” weapon. The Bullpup was roll-stabilized and visually guided by the pilot or weapons operator using a flare on the back of the missile to track the weapon in flight while using a control joystick to steer it toward the target using radio signals. Therefore, the pilot had to stay on course as the Bullpup was steered to its target, exposing him to enemy fire. Some F-105s carried 750-pound bombs, but these were less precise, and when they did hit the bridge, they caused only minor damage. Some bombs fell on nearby roads, causing traffic to be stopped for a few hours. This was the only material result of the raid, at the cost of one F-100 and one RF-101 being shot down.

A new attack was scheduled for the next day. This time 80 planes were engaged, including 48 F-105s, carrying only 750-pound bombs in the wake of the Bullpups’ inadequacy. The raid was again an exercise in great precision, but despite receiving more than 300 hits, the bridge refused to fall. Minor damage caused traffic to be interrupted for a few days. This action cost the U.S. Air Force three F-105s. One was lost to ground fire, but the two shot down by supposedly obsolete Mig-17s would lead to a significant reexamination of fighters suited to dogfighting.

Weapons and “Route Packages”

To limit airspace conflicts between Air Force and Naval strike forces, North Vietnam was divided into six target regions called “route packages,” each of which was assigned separately to either the Air Force or Navy—the other service was forbidden to intrude. Each controlled its own sectors of airspace in North Vietnam and Laos. The Military Assistance Command-Vietnam, MACV, controlled the air war in Route Pack 1. The Navy controlled the air war in Route Packs 2, 3, 4, and 6B. Pacific Air Forces controlled air activities in Route Packs 5 and 6A. The widespread use of long-range bomber forces was controlled by the Strategic Air Command. The Thanh Hoa area was allocated to the Navy. Between 1965 and 1968, when President Lyndon B. Johnson temporarily called off air raids against North Vietnam, the bridge was a regular objective for Navy strikes. Different types of aircraft were engaged in these strikes, including A-3 Skywarriors, A-4 Skyhawks, A-6 Intruders, F-4 Phantoms, and F-8 Crusaders.

Several types of weapons were launched at the bridge, including television-guided AGM-62 Walleye glide bombs that, unlike the Bullpup, allowed the pilot to veer off the missile’s track to avoid enemy fire but still guide the missile. Unfortunately, none of the early Walleyes had the precision and power to destroy the bridge permanently. Several times, traffic over the bridge was interrupted, but each time the resourceful North Vietnamese quickly repaired the damage.

Early use of the Walleye did have some notable successes, such as the March 11, 1967, strike against the Sam Son barracks by a U.S. Navy A-4C in which a bomb entered through a window and blew apart the building. The very next day, three A-4s attacked the Dragon’s Jaw with direct hits, but the bridge stood relatively unscathed. Some 825 pounds of high explosives still lacked the punch to knock out concrete and steel bridge supports. The Walleye was a temperamental weapon, effective where there was good visual contrast but less reliable if the weather was overcast or if dust from previous explosions obscured the target.

In 1972 the larger Walleye II, nicknamed Fat Albert, entered service. Its 1,900-pound high-explosive warhead was hefty enough to take down the Dragon’s Jaw bridge. Walleye II offered the Navy and Air Force another new capability—the ability to stand off from the target. Walleye I had a range of 16 miles, while Walleye II had a range of 35 miles, enabling jets to launch them from outside the lethal envelope of flak.

Commander James Stockdale’s War

Commander James Stockdale’s Air Group 16 took up an unrelenting challenge to bomb and destroy enemy military and industrial assets. In his book, In Love and War, Stockdale remembers: “A week later we made a series of daily strikes against the bridge. This was a big, tough old rail highway span that crossed the wide Song Ma River just northwest of the coastal town of Thanh Hoa. We had bombed this old structure before and it seemed to be our nemesis. We hit both the bridge decks and superstructure with Bullpup guided bombs, 500-pound bombs, and even a few 1,000-pound bombs, but to no permanent avail. From the air, one could look down and see its structural members broken and bent, but the bridge continued to stand there week after week, deck planking replaced during the nights and truckloads of imported munitions from the seaport of Haiphong streaming across it heading west and south for delivery to the Viet Cong. Next time I would instruct the Marine Crusaders to carry our new 2,000-pound bomb load.”

Stockdale echoed the sorrow of seeing fellow pilots go down as a result of the intense ground fire: “On Monday, August 23, four more of our Skyhawks were badly hit but luckily made it back aboard. Then things started turning worse. On August 26 we lost young Ed Davis, just three years out of Annapolis; Ed had been married only a few weeks before we left San Diego. He was on a near-vertical bombing run on a dark night in a Spad, was hit by flak as he passed through two thousand feet, and was last heard from as he passed a thousand feet calling ‘Mayday,’ struggling to get out of his burning airplane. Ed’s flight leader saw the fireball when his plane hit the ground; we sent search planes back to the scene at first light the next morning and all that could be seen was a scorched place on the earth where the plane was consumed by fire. I sent the first KIA message of this time period, and Ed’s wife became a legal widow.”

By September 9, 1965, Stockdale had already flown 201 missions in a variety of aircraft. This translated into a combat mission every two days. On this day, he was slated to fly a strike on the Dragon in an A-4 Skyhawk. His group was aboard the USS Oriskany, which was operating off the North Vietnamese coast on Yankee Station, from which position carriers launched aircraft for inland strikes. The strike was to employ 37 aircraft. The order came to “Man your planes,” and the aircraft were readied. Included were electronic-warfare countermeasure aircraft and tankers allowing the thirsty aircraft to make it back to the carriers.

On the subsequent attack, Stockdale went in fast and low at 400 knots and under 2,000 feet. He was a few miles inland over the coastline railroad when he released his bombs and began a gentle ascent. He began taking fire from an enemy 57mm antiaircraft gun. The coast was only three miles away, but the aircraft was too badly damaged to make it over the water. As his stricken aircraft became uncontrollable, Stockdale ejected and quickly found himself in a town where angry locals beat and shot him. His leg was shattered from his ejection and parachute landing.

Stockdale and a growing number of Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps pilots became prisoners of war and were relocated to Hoa Lo Prison in Hanoi, which they famously dubbed the Hanoi Hilton. Their stay as “guests” was just beginning. This was the last time that Stockdale would see the outside world without a blindfold for several years. (In 1992, he would become independent presidential candidate Ross Perot’s running mate.)

Operation Carolina Moon: An Innovative Attack

Even when the fighter-bombers were able to score a direct hit on the bridge, a 750-pound bomb was simply not powerful enough to drop the span. In May 1966, an innovative attack dubbed Operation Carolina Moon was planned by the Air Force. A new weapon was to be used: a magnetic mine that implemented a new energy-mass-focusing concept. The plan was to float the mines down the Song Ma River until they reached the bridge, where, it was hoped, magnetic sensors would set off the charges and wreck it permanently. The only aircraft with a large enough hold to carry these weapons was the lumbering C-130 Hercules transport, so the operation was planned to take place at night to reduce its vulnerability.

The plan necessitated two C-130 aircraft dropping the weapon, a large pancake-shaped device eight feet in diameter, 21/2 feet thick, and weighing 5,000 pounds. The C-130s would fly below 500 feet to evade radar along a 43-mile route, making the C-130 vulnerable to enemy attack for about 17 minutes before dropping the bombs.

Because the slow-moving C-130s would need protection, F-4 Phantoms would fly diversionary attacks to the south, using flares and bombs on the highway immediately before the C-130 was to drop its ordnance. The F-4s were to enter their target area at 300 feet, attack at 50 feet, and pull off the target back to 300 feet for subsequent attacks. Additionally, an EB-66 was tasked to jam the radar in the area during the attack period. Since Risner had been shot down in September, 15 more pilots had been downed in the bridge region. Everyone knew it was hot.

The first C-130 was to be flown by Major Richard T. Remers and the second by Major Thomas F. Case, both of whom had been through extensive training for this mission at Eglin Air Force Base, Florida, and had been deployed to Vietnam only two weeks before. Ten mass-focus weapons were provided, allowing for a second mission should the first fail to accomplish the desired results. Last-minute changes to coincide with up-to-date intelligence included one that would be very significant: Remers felt that the aircraft was tough enough to survive moderate antiaircraft artillery hits and gain enough altitude to bail out if necessary. Case agreed that the aircraft could take the hits, but he felt the low-level flight would preclude a controlled bailout. Remers decided that his crew would wear parachutes and stack their flak vests on the floor of the aircraft. Case decided that his crew would wear flak vests and store their parachutes.

On the night of May 30, Remers and his crew, including navigators Captain Norman G. Clanton and 1st Lieutenant William “Rocky” Edmondson, departed Da Nang at 12:25 am and headed north under radio silence. Although the “Herky-bird” encountered no resistance at the beginning of its approach, heavy but inaccurate ground fire was encountered after it was too late to turn back. The five weapons were dropped successfully in the river, and Remers made for the safety of the Gulf of Tonkin. The operation had gone flawlessly, and the C-130 was safe. Although the diversionary attack had drawn fire, both F-4s returned to Thailand unscathed.

The crew’s excitement was short-lived because recon photos taken at dawn showed that there was no noticeable damage to the bridge; nor was any trace of the bombs found. A second mission was planned for the night of May 31. The plan for Case’s crew was basically the same with the exception of a minor time change and slight modification to the flight route. A crew change was made when Case asked Edmondson, the navigator from the previous night’s mission, to go along. Case’s crew departed Da Nang at 1:10 am.

The crew aboard one of the F-4s to fly diversionary included Colonel Dayton Ragland. Ragland was no stranger to conflict when he went to Vietnam. He had been shot down over Korea in November 1951 and had served two years as a prisoner of war. Having flown 97 combat missions on his tour in Vietnam, Ragland was packed and ready to go home. He would fly as “backseater” to 1st Lieutenant Ned R. Herrold on the mission to give the younger man more combat flight time while he operated the sophisticated technical navigational and bombing equipment. The F-4s left Thailand and headed for the area south of the Dragon’s Jaw.

About two minutes prior to the scheduled C-130 drop time, the F-4s were making their diversionary attack when crew members saw antiaircraft fire and a large ground flash in the bridge vicinity. Case and his crew were never seen or heard from again. In addition to Case, those lost included 1st Lieutenant Harold J. Zook, co-pilot; 1st Lieutenant William Edmondson, navigator; Captain Emmett R. McDonald, navigator; 1st Lieutenant Armon D. Shingledecker, navigator; Staff Sergeant Bobby J. Alberton, flight engineer; Airman First Class Elroy E. Harworth, loadmaster; and Airman First Class Philip J. Stickney, loadmaster. During the F-4 attack, Herrold and Ragland’s aircraft was also hit. On its final pass, the aircraft did not pull up but went into the sea in a ball of fire.

Reconnaissance crews and search and rescue scoured the target area and the Gulf of Tonkin the next morning but found no sign at all of the C-130 or its crew. Rescue planes spotted a dinghy in the area where the aircraft had gone down, but no signs of life. Even worse, the bridge still stood. No more C-130s were employed.

Operation Linebacker: Destroying the Bridge

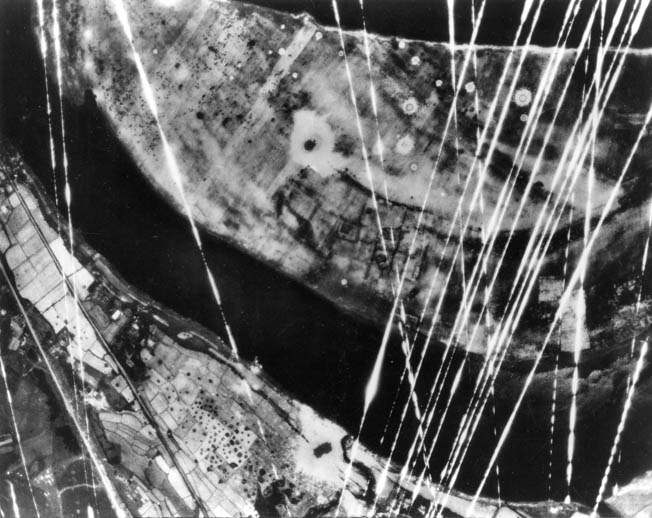

Between 1968 and 1972, bombing of North Vietnam was discontinued, enabling the North Vietnamese to repair their infrastructure, including the Thanh Hoa Bridge. With the communist invasion of South Vietnam in 1972, a new bombing campaign was instituted: Operation Linebacker. On April 27,1972, 12 Phantoms of the 8th Tactical Fighter Wing, based at Ubon, Thailand, attacked the Thanh Hoa Bridge, with eight of them carrying Paveway laser-guided bombs (LGBs). The raid was carried out without a hitch, and when the dust of the explosions had cleared, it became apparent that the bridge had been dislodged from its western abutment, dropping halfway into the river.

To complete its destruction, a second attack was scheduled for May 13, 1972. On the appointed day, 14 Air Force F-4 Phantoms headed for the Dragon’s Jaw. They were carrying nine 3,000-pound LGBs, 15 2,000-pound LGBs, and 48 conventional 500-pound bombs. After the ordnance had been dropped, the bridge’s western span had been knocked completely off its 40-foot concrete abutment. The superstructure was heavily damaged, as were the bridge approaches. The bridge would be out of action for some time.

Air Force Colonel Dick Horne led one last raid on October 6, 1972. This time, Navy A-4s successfully delivered six 2,000-pound LGBs onto the target. After this, the Thanh Hoa Bridge was considered permanently destroyed and removed from the target list. The North Vietnamese made various fanciful claims about how many planes they shot down, but the U.S. military recognizes the loss of only 11 aircraft during attacks against the bridge. However, the concentration of air defense assets also took its toll on passing aircraft, and an estimated 104 American pilots were shot down over a 75-square-mile area around the bridge during the war.

873 Air Sorties

In all, some 873 air sorties were flown against the bridge, and it was hit by hundreds of bombs and missiles before being finally destroyed. It became a symbol of resistance for the North Vietnamese, and various legends of invincibility were attached to it. For American planners, it became an obsession, despite the missions’ unpopularity among pilots.

One of the participants in the 1972 strikes was Lt. Cmdr. (later Admiral) Leighton W. “Snuffy” Smith, Jr. In John Darrell Sherwood’s book, Afterburner, Smith recalled his participation in the intense September 10 strike, during which he had to make a tough decision. He and another pilot were acting as rescue combat air patrol and were sent in to locate a downed pilot, Lieutenant (jg) Steve Musselman. “We got up and made one pass through the area, and we saw the wrecked aircraft,” Smith said. “There was absolutely no way anybody was going to be able to get in there and get Musselman, because he was right down in the middle of a flat area—very close to the city as far as we could determine. There was a hell of a lot of ground fire. There were a lot of SAMs. There were MiGs in the air, but we didn’t see any. So I had to make the decision that it would not be prudent to go in and try to pick up Musselman. As it turned out, he never came back out. The supposition is that he was shot while descending in his parachute.”

Smith further recalled his role in the October 6 strike, which proved to be the Dragon Jaw’s demise. He and his wingman, Marv Baldwin, carried two 2,000-pound Walleyes, while the two other pilots, Don Sumner and Jim Brewster, carried standard 2,000-pound bombs. “We rolled in simultaneously,” Smith recalled. “Pulled the power back, popped the speed brakes, and we got our scopes locked-on to the bridge and I said, ‘Lock-on.’ Once everyone confirmed that they had locked-on, I counted ‘Three, two, one, launch,’ and Marv and I both pickled them at the same time. Then Don and Jim popped up and they began their roll-in. They hit the bridge on the west side of the center piling and that’s where it broke in half. In fact there was so much smoke and crap around there, we didn’t know whether we’d hit it and done any damage or not. Later that afternoon, an RA-5 Vigilante came through and took a picture, and when we looked at them, we finally knew that the bridge was down for good.”

For his efforts, Smith was awarded his second Distinguished Flying Cross. The USS America and its Air Wing 9 were awarded the Meritorious Unit Commendation upon their return.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments