By Kerry Skidmore

Historian Christian Wolmar concludes that the two world wars could not have been fought to such devastation without military railways, in his book Engines of War. In wars, from the Crimean to the arrival of the jet engine, railways were a dominant technology. Consequently, the military that best employed its railways to transfer fresh troops and supplies to the point of greatest need usually prevailed.

The assault on Hitler’s Fortress Europe saw the strategic use of military railways reach its peak. By 1944, all major armies had reached new levels of mobility and sophistication. A military command could launch devastating attacks by highly mobile armored units, supported by tactical artillery and air support and all supplied by rail. In this type of warfare, rapid transport of fuel, largely carried in millions of five-gallon Jerry cans, and ammunition were tantamount for success. Correspondent Ernie Pyle noted that American artillery fired $10 million worth of ammunition a day. These quantities could only be successfully moved by rail.

The Crucial Port of Cherbourg

For Operation Overlord, the Normandy invasion, infantry-related supplies had been stockpiled in England to be landed at the artificial harbors—the miraculous Mulberries— and moved by truck to the troops. The immediate plan to integrate railways into the supply chain was to use the port of Cherbourg, sitting at the top of the Cotentin Peninsula, and discontinue the use of the beaches as supply depots as soon as possible. While Cherbourg was historically a tourist debarkation port and its cargo capabilities were limited, there were excellent deep-water piers there and an inner harbor protected from the North Sea’s storms.

Cherbourg was to be opened within a week. But the Germans still had strong infantry and armored units stationed along the entire peninsula, and Hitler had a different war plan. He ordered Fortress Cherbourg to resist to the last and that the port facilities be destroyed. After a desperate defense the port finally fell on June 28, 1944. When American engineers arrived in the city, they found that the methodical German garrison had done a masterful job of wrecking the port and facilities

The main deep-water piers—Quai-du-Normandie, Quai-du-France, and Quai-du-Homet—and the entire arsenal area were expertly blocked with sunken hulks, demolished cranes and equipment, and tons of concrete blasted on top of the wreckage. In the inner harbor, only the seaplane ramp west of the great quays and the reclamation area to the east were undamaged. Thousands of magnetic, acoustic, and contact mines were sown in the waters, shoreline, and facilities. The engineers were also confronted with scores of the new “Katy” mines, which were specifically designed to prevent minesweeping.

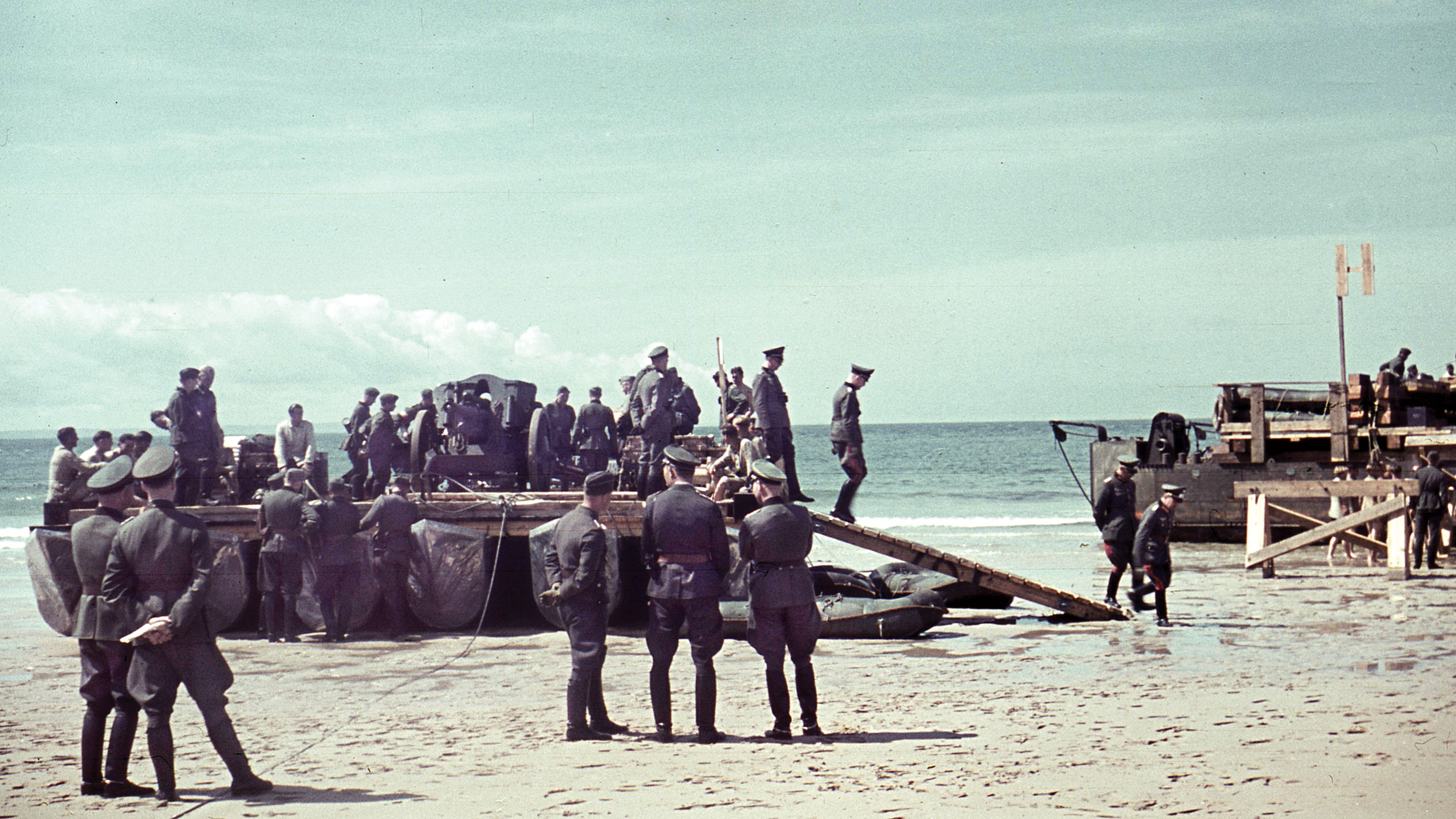

Adding to the invaders’ problems, the American Mulberry at Omaha Beach had been destroyed by a hurricane-force storm on June 21. For the American forces, the only good alternative was to ferry cargo to the beaches using the amphibious 2.5-ton DUKW (military abbreviation for 1942, utility, front and rear wheel drive). Soon cargo ships were offloading onto the ubiquitous DUKWs and all varieties of landing craft and ferried to shore.

At Cherbourg, the Navy succeeded in clearing lanes to the seaplane ramp and the sandy beach (Terre Plein) in the reclamation area, losing several minesweepers in the effort. More DUKWs and landing craft were brought in, and offloading began onto these beaches. The supplies quickly piled up awaiting transport. While these smaller craft had no problem landing, the 24-foot tides at Cherbourg made landing of heavy equipment, trucks, and trains difficult. Their transfer from the offshore ships was a slow and dangerous process.

Colonel Bingham’s Breathing Bridge

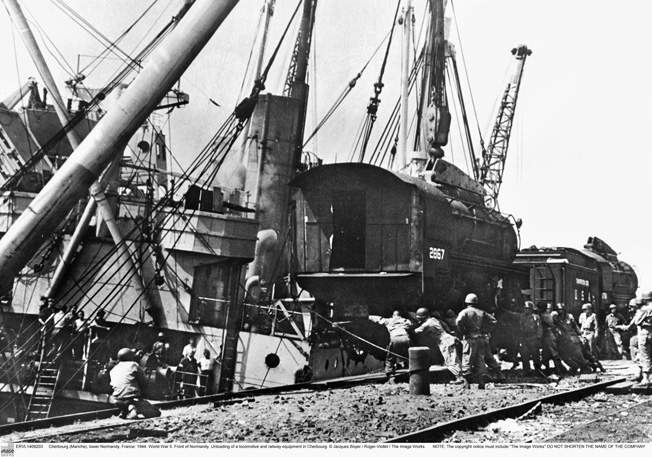

Trains, especially 70-ton steam locomotives, presented additional challenges because their long fixed frames required a flat landing area. The standard method was to offload from a berthed Liberty or Seatrain ship with heavy cranes and I-beams directly onto tracks on a dock. Alternatively, locomotives could be loaded onto a shallow draft craft and pulled onto the dock, provided the ship deck and dock were nearly level. This method limited landings to two times a day if the seas permitted.

Colonel Sidney H. Bingham, manager of the New York subway system in peacetime, devised a “breathing bridge” to land railway rolling stock even to the low tide line. A flange-wheeled ramp, which would connect to rails laid in an LST (Landing Ship, Tank), was run down to the lowest tide line and mated to an LST’s bow ramp. By July 8, Bingham had four of the breathing bridges operating in the Terre Plein, each offloading 22 rail cars in 21 minutes.

during the final months of World War II, allowing much-needed troops and supplies to move by rail. In this photo, a locomotive is unloaded from a freighter at the major port city of Cherbourg, France.

With their heavy equipment ashore, the Corps of Engineers quickly cleared the roads and the railways in town. Soon a steady stream of trucks moved the backlogged supplies to the front, then as far south as Carentan. Except for a collapsed railway tunnel, the railway was surprisingly intact; several locomotives and a quantity of rolling stock were found undamaged (among them were six “General Pershing” 2-8-0 locomotives given to the French at the end of World War I). The engineers repaired the 15 miles of existing track and laid new track to the reclamation area, doubling port’s rail capacity.

A Front Thirsty for Supplies

At the front the Allies still were making little progress against the Germans, slogging their way through the Bocage, or hedgerow country. However, reconnaissance and intelligence intercepts revealed that the German defenses west of Caen were unraveling. To break the six-week-old stalemate, the American 12th Army Group, commanded by General Omar Bradley, launched Operation Cobra.

On July 25, VII Corps, commanded by General J. Lawton Collins, attacked west of St. Lo and quickly broke through the German defenses. Carentan was taken on the 28th, and the coastal city of Avranches fell on the 30th. With the German defenses south of Caen rapidly collapsing, General Bradley activated the Third Army to exploit the breakthrough.

General George Patton had been selected to command the Third Army on January 22, 1944. From March to July, he had played the role of commander, First U.S. Army Group (FUSAG), the hugely successful ruse that kept the Germans tied to defending the Pas-de-Calais. Patton accompanied VIII Corps commander General Troy Middleton south to Avranches during the breakthrough. When the Third Army was activated on August 1, Patton was ordered to send the VIII Corps west to take the Brittany Peninsula while he took the remainder of the Third Army eastward. Its objective was the transport center at Le Mans. Patton’s mission was to trap and destroy the German Seventh Army, commanded by General Gunther von Kluge, west of the Seine River.

On August 7, Kluge counterattacked westward in a desperate attempt to cut Third Army’s supply line at Avranches. Bradley, well briefed on the coming attack by Army intelligence, saw this threat as an opportunity to trap the Germans. On August 8, Patton was ordered to turn Third Army north to Argentan while Montgomery’s Canadian forces moved south to Falaise. The U.S. XV Corps, under General Wade Haislip, having taken Le Mans on August 8, raced north and captured the German supply depot at Alençon on the 12th and approached Argentan on the 13th. From Mayenne, VII Corps moved northeast to cover XV Corps’ left flank; Patton was ready to close the trap.

What followed was one of the most controversial episodes of the war. The Canadians could not get to Falaise, but Third Army was held at Argentan. Much of the German Seventh Army escaped after suffering tremendous casualties. As early as the 14th, Bradley was certain the Germans had gotten away, so he sent Patton east in pursuit. Fuel was now in short supply. Patton’s armor consumed an average of 336,500 gallons of gasoline a day, and he needed trains to deliver it all.

The Military Railway Service

The Military Railway Service (MRS) was developed in response to the lessons of World War I. Organized into grand divisions, each with four or five railway operating battalions (ROB) and a railway shop battalion (RSB), each battalion was sponsored by a Class I American railroad and placed in reserve status under the sponsoring railroad’s name. Upon their activation, the railroads’ supervisors became the battalion officers, and the inducted employees reported to platoons relating to their railway specialty. Each battalion had 18 officers and 803 enlisted men.

Each battalion had a headquarters company, including dispatchers and signal management; Company A, track and signal maintenance; Company B, equipment maintenance, including car and locomotive repairs; Company C, train crews and train masters. The RSB’s 23 officers and 658 enlisted men were strictly back shop repair and erection companies.

The Allies had begun ferrying railway equipment to England in 1942. By June 1944, some 900 steam locomotives, 651 Whitcomb diesels, and 20,000 prefab cars were ready to ship to Normandy. As the 2nd MRS, ultimately responsible for operations in northern France, arrived in England, they were put to assembling rolling stock and learning the operating procedures for the European railways. Unfortunately, many units arrived just as the invasion was imminent and left for France with no tools and only the clothes on their backs.

France’s Railway Infrastructure in Ruins

Before the war France had 26,000 miles of standard-gauge track. Many of the lines were double tracked for simultaneous bidirectional operations. While French rolling stock was lighter and far older than that on American railroads, the French railways were considered excellent. The 1940 blitzkrieg of France was successful in part because the Germans used the interconnected railways to provide logistical support for their armies. As the Overlord invasion approached, the French railways, now an integral part of the German defenses, were heavily bombed and sabotaged by partisans. Despite these interdiction campaigns, German engineers proved quite adept at keeping some critical lines open to the end. As the Allies pushed them out of western France, these engineers proved equally adept at destroying what little remained.

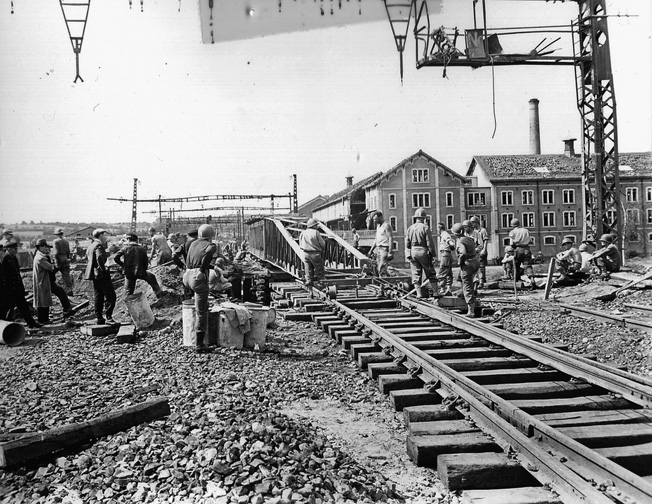

As the breakout had advanced, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers service regiments followed closely. These service units, often under fire, worked to open roads, blocked tunnels, wrecked track, and destroyed bridges. Behind them the railway operating battalions struggled to restore rail service. Allied practice at this time was to repair indigenous operating equipment and use the system’s experienced railway workers to operate their railways.

However, it was discovered that the entire French railway infrastructure had been destroyed or rendered ineffectual. A high percentage of the bridges, rails, and ties were wrecked. Few water facilities and pumps were intact. There was no coal, no electricity, and the signal systems, phone lines, and other equipment were systematically wrecked.

In the yards, the switches and the rail frogs were dynamited, effectively preventing their use; destroyed rolling stock blocked everything. Many of the French railway workers had been hauled off by the retreating Nazis; those remaining had taken their tools and were hiding.

Restoring the Railway Lines

The railway battalions were forced to start from scratch. They had to build their own tools and then develop facilities. Many were primitive but ingenious. In several areas local fire departments were called out to furnish water for the locomotives. By July 31, the rail line from Cherbourg to Avranches was opened but far from totally functional. Early operations were often compared to a second-rate Toonerville Trolley.

The five-man train crews set out with a case of K-rations in quarter-mile-long trains carrying 1,000 tons of fuel or ammunition over barely repaired track, often not knowing whether there was track ahead. At night, they moved blacked out, and conducted switching by using flashlights, cigarette lighters, or even lit cigarettes. The crews often went 90 hours on a single trip. Wrecks, from minor derailments to volcanic conflagrations, were frequent and completely halted railway operations.

As the Third Army moved east, the VIII Corps in Brittany and the First Army in the north were also moving rapidly. Each of these campaigns was along a major rail line and on each of them Corps of Engineers service regiments were frantically trying to restore the lines to service. In addition to this damage, equipment and troop shortages in both the engineering and the railway battalions also hampered efforts to restore service.

By July 31, the 2nd MRS still had only one grand division between Cherbourg and Avranches. Only 40 diesel and steam locomotives and 184 freight cars had been shipped from England. The Allies had only captured and repaired 100 locomotives, 1,641 freight cars, and 76 coaches. As the railways were increasingly unable to provide direct support to the advancing armies, trucks and even airlifts became the principal means of getting supplies to the tanks This situation hampered American operations until the end of the war.

“Will Finish at 2000”

The Third Army’s path invested the main railway line from the Brittany ports to Paris. This double-tracked railway ran through Avranches, Rennes, Laval, La Chappelle, and Le Mans. The German presence in the area consisted of rearguard units trying to hold open the escape routes for forces withdrawing east of the Seine River. These units only slowed the Third Army by further wrecking the roads and railways as they pulled back.

By August 12, the repairs of the Cherbourg to Pontaubault railway were still far from complete. On just the one section near Folligny, 2,000 Corps of Engineers and ROB troops were working nonstop on the repairs. At sunset on the 12th, Colonel Emerson C. Itschner, commanding the Corps of Engineers regiments in northern France, received a remarkably prescient instruction from Third Army:

“General Patton has broken through and is striking rapidly for Paris. He says his men can get along without food, but his tanks and trucks won’t run without gas. Therefore the railroad must be constructed to Le Mans by Tuesday midnight. Today is Saturday. Use one man per foot to make repairs if necessary.”

Itschner had just 75 hours to open a 135-mile-long rail line. For this task he had the 347th and 322nd Engineer General Service Units (the 2,000 men near Folligny). Another 8,500 troops were scattered all over the Allied lodgment. These units, and all the equipment that could be rounded up, were ordered to rush south.

At daylight on the 13th, Itschner flew over the area searching for the route that could be repaired by the deadline. The damage to the high viaduct at Laval immediately eliminated the main line. Itschner was forced to select an alternate route over secondary single track lines from Pontanaubault to St. Hilaire-du-Harcouet, south to Fougeres, east to Mayenne, and south to rejoin the main line east of Laval and on into Le Mans.

This route was in little better condition. Five bridges were down. The most serious was an 80-foot span at St. Hillarie-du-Harcourt, but Itschner believed all could be repaired in time. All day on Sunday and Monday elements of the 392nd, 390th, and 95th Engineer Regiments— now some 9,000 men—began arriving piecemeal and were soon working on all the trouble spots simultaneously.

With six hours remaining before the deadline, Itschner flew over the line. Below him the engineers had spelled out “will finish at 2000” in white concrete. Thirty-one gasoline-loaded trains left Folligny at 1900 hours on the 14th and began crossing the St. Hilaire-du-Harcouet Bridge at midnight. Despite nine delays, the quarter-mile-long trains arrived at 30-minute intervals in Le Mans beginning at midnight on the 15th.

“Toot Sweet Express”

The Corps of Engineers had completed a dramatic achievement in military railway construction. On their rails the ROBs, the last leg anchored by the 740th Railway Operating Battalion, had transited the 135 miles using improvised rail lines to deliver the important fuel on time. For its effort, the 740th was to bring the first train into Paris on August 30. A remarkable opportunity, in a remarkable month, resulted in a total effort and assured that Patton would continue to pursue and destroy the Germans.

The U.S. XII Corps, commanded by General Manton Eddy, took Orleans on the 16th, and XX Corps, under General Walton Walker, occupied Chartres on the 18th. By August 24, the Third Army had four bridgeheads across the Seine, 30 miles south of Paris.

On August 25, the Third Army resumed its drive eastward toward Metz as far as logistics permitted. This drive created something of a reversal of roles for the logistical support chain. The railways east of the Seine were in excellent condition, while their western counterparts remained primitive, still relying on single-track lines and hand signaling and lacking rolling stock.

In response, Red Ball Express truck transport was initiated to move supplies to Paris where they were loaded onto trains and moved eastward. Unfortunately, even this distance was too great for the trucks to support the Third Army indefinitely. By the end of August, 90 to 95 percent of all supplies were still on the beaches or at Cherbourg, 300 miles from the Third Army spearheads. The crisis reached a climax at the end of August; nothing was moved eastward from August 27 until September 2. Third Army, at the German frontier, was out of fuel.

Special cargos were loaded onto expedited trains, affectionately named the “Toot Sweet Express.”

Eisenhower’s Decision: Montgomery over Patton

Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower had to make a choice; give the available fuel to Patton or the British 21st Army Group under General Bernard L. Montgomery in the north. For reasons more political than strategic, Eisenhower gave his erstwhile subordinate Montgomery all the available fuel to conduct his ill-conceived Operation Market-Garden, the ground and airborne invasion of Holland to seize vital bridges for a strike at the Ruhr, the industrial heart of Germany.

Third Army, which many historians believe could have continued to advance, would not receive fuel again until the port of Antwerp, Belgium, became fully operational later in the year. Thus, despite the somewhat anticlimactic end, the combat engineers and railway workers recorded a monumental achievement in the summer of 1944.

Hi

I did write previously but the correspondence tailed off..I am v anxious to contact the writer of this article to see where they got their material as I am writing a book on railways and the Normandy invasion for which this story will be a key part… I do hope you can help

Christian Wolmar

My father Gilbert Batman was an engineer on the rails of France and Germany, thank you for this site. i have learned much thank you.

Hi there

Do you have any accounts of what he did – any material at all – which I could use for the book i am writing on the Normandy invasion and the rebuilding of the railways…I would be most grateful.

Christian Wolmar