By Christopher Miskimon

The smoke had barely cleared from the battlefields of North Africa when the victorious Allies turned their attention northward to Europe. American planners were eager for the decisive battle against Nazi Germany in Western Europe, which could only happen after a successful invasion across the English Channel.

The British high command felt otherwise, unconvinced their combined forces were yet ready to face the Wehrmacht. Instead, they advocated more action in the Mediterranean Theater, where the Germans were weaker but still able to interdict the necessary shipping traffic Britain needed for its war effort. Attacking this “soft underbelly” in either Italy or the Balkans would relieve pressure on the British Empire as well as further blood the Allied troops for the eventual showdown against Germany. It would also draw enemy forces from the Eastern Front, where at great cost the Soviets had the bulk of the German ground forces occupied.

Additionally, Italian resolve was wavering; if they could be taken out of the war it would ease Allied efforts considerably.

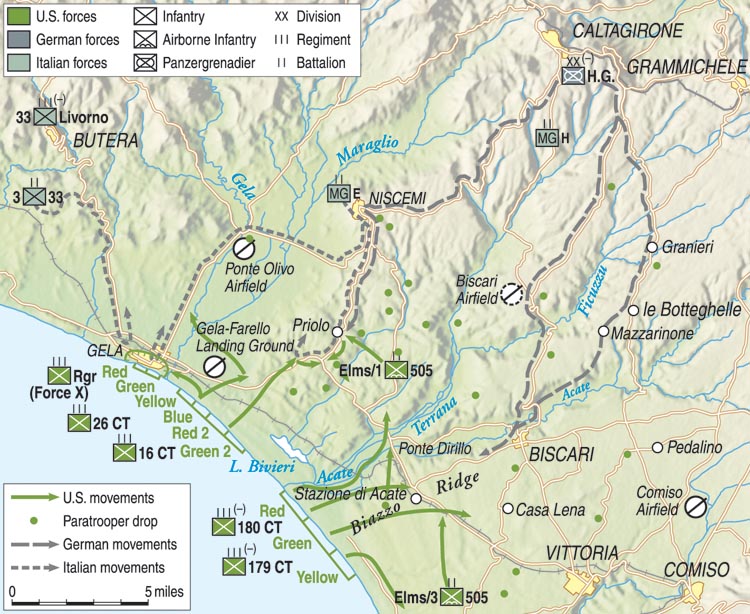

After much debate the decision was made to invade the Italian island of Sicily, only 90 miles north of the African coast. Seizure of the island would provide a steppingstone toward the Italian mainland. There were about 250,000 Axis troops defending Sicily, most of them Italians with a stiffening of German troops and a large number of Luftwaffe personnel. Roughly half the Italians were organized into infantry divisions while the rest formed either coastal defense or rear-echelon support units.

The Defenses of Sicily

The coast defense formations were relatively immobile and were intended to act as a delaying force against any invaders, giving time for the regular divisions and the Germans to react decisively. The largest German units present for the landings were the Hermann Göring Panzer Division and the 15th Panzergrenadier Division. Between them they possessed about 150 tanks along with infantry and supporting artillery. Included in the totals were 17 heavy Tiger tanks, originally earmarked for North Africa but retained in Sicily after the Axis forces surrendered in Tunisia some two months earlier.

On the Allied side, two armies were scheduled for the invasion. The British Eighth Army chose four infantry divisions and a separate brigade for its landings along the southeastern coast of Sicily. The U.S. Seventh Army selected three infantry divisions for the landing with an armored division as a floating reserve. Both nations had additional airborne contingents for landings behind the beachheads.

The Americans also brought along their new light infantry/commando force, the Rangers. Formed in the beginning of 1942, the Rangers were to be a Yankee version of the famed British Commando forces used for raids and special operations missions. The two groups had worked together in training, and a 50-man detachment had accompanied the Canadian/ British force that raided Dieppe in August 1942. Commanded by Lt. Col. William O. Darby, by the time of the Sicily invasion the 1st Ranger Battalion had expanded into a three-battalion force composed of the 1st, 3rd, and 4th (2nd Battalion was formed in the United States).

The 32-year-old Darby was an Arkansas native who had graduated from West Point and was beloved of his men, who had nicknamed him “El Darbo.” Darby officially commanded 1st Battalion with two majors running the others, though Darby was considered the entire Ranger force’s nominal leader. Now two battalions of Rangers would have a chance to make their own amphibious assault on the coastal town of Gela in the center of the American landing area.

Force X

During the war Gela was a fishing town of about 30,000 people. It had seen war before, having been sacked by the Carthaginians in 405 bc during a war against Greece. The city itself sat directly on the shoreline just west of the mouth of the Gela River. A concrete pier extending some 900 feet into the sea split the town almost directly in half. The shore in the area sloped out to sea gradually, so in many places a force landing there would have to wade a considerable distance from their landing craft, risking enemy fire all the way.

Sandbars dotted the area, further impeding the approach of amphibious vessels. There was a crossroads at Gela where two branches leading generally north joined with a coastal road. Intelligence showed the presence of enemy coastal guns near Gela as well. Aerial photographs showed several fishing boats sitting on the beach, indicating an absence of mines.

To seize this vital objective, two battalions of Rangers were selected, the 1st and 3rd. They were combined to form Force X for the Gela operation. Reinforcing them would be three companies of the 83rd Chemical Mortar Battalion, equipped with the 4.2-inch (107mm) mortar, capable of firing either smoke or high-explosive ammunition. Because of their origins in World War I as weapons for firing gas and smoke rounds, they were generally referred to as “chemical mortars” by U.S. soldiers. The mortar’s high rate of fire and portability made it a perfect weapon for supporting the fast-moving Rangers, and the 83rd would become practically a dedicated fire support unit for Darby’s men, earning the nickname “Artillery of the Rangers” for its service throughout the Italian campaign.

Also joining Force X was the 1st Battalion, 39th Engineer Regiment, a combat engineer unit that could clear mines, create obstacles and defensive positions, and fight at need. Together Force X was essentially a small ad hoc regimental combat team.

The entire force would be attached to the 1st Infantry Division for the invasion. That division, commanded by General Terry Allen, was composed of the 16th, 18th, and 26th Infantry Regiments along with supporting artillery, attached armor, and other reinforcing units. The landing beaches for the division itself were to the east of Gela.

The Plan to Take Gela

Darby and the 4th Rangers commander, Major Roy Murray, formulated a plan for taking the town by splitting it in half. The long pier that jutted into the Mediterranean from nearly the center of Gela made a perfect boundary marker for the two battalions. Darby’s 1st Battalion would land on the west side of the pier and seize that side of the town while Murray’s troops would land east of the pier and seize the other half. The coastal guns were west of the pier and would be taken by Darby’s men. The 39th Engineers would come ashore and begin clearing mines and obstacles. Lastly, the chemical mortar companies would set up positions and be ready to give fire support.

Darby organized his force to land in successive waves. As each came ashore they would attend to their specific mission, sometimes passing through the wave ahead of them. The first wave would consist of Companies C, D, E and F (Ranger battalions were organized with six rifle companies). These Rangers were to clear the beach and move into the town as far as the main street. Following in the second wave were A and B Companies, which were to pass through the first wave and move west to knock out the coastal battery on the edge of Gela.

The engineers were in the third wave with the chemical mortars in the fourth. The landing craft were to be guided in by a submarine that would surface and display a red light on its stern for them to steer by. The 4th Battalion did not have any coastal guns or other large objectives to worry about, so Murray’s Rangers would land in two waves. Companies A, B, and C would constitute the first group, accompanied by a detachment of headquarters troops, while D, E, and F would land in the second echelon.

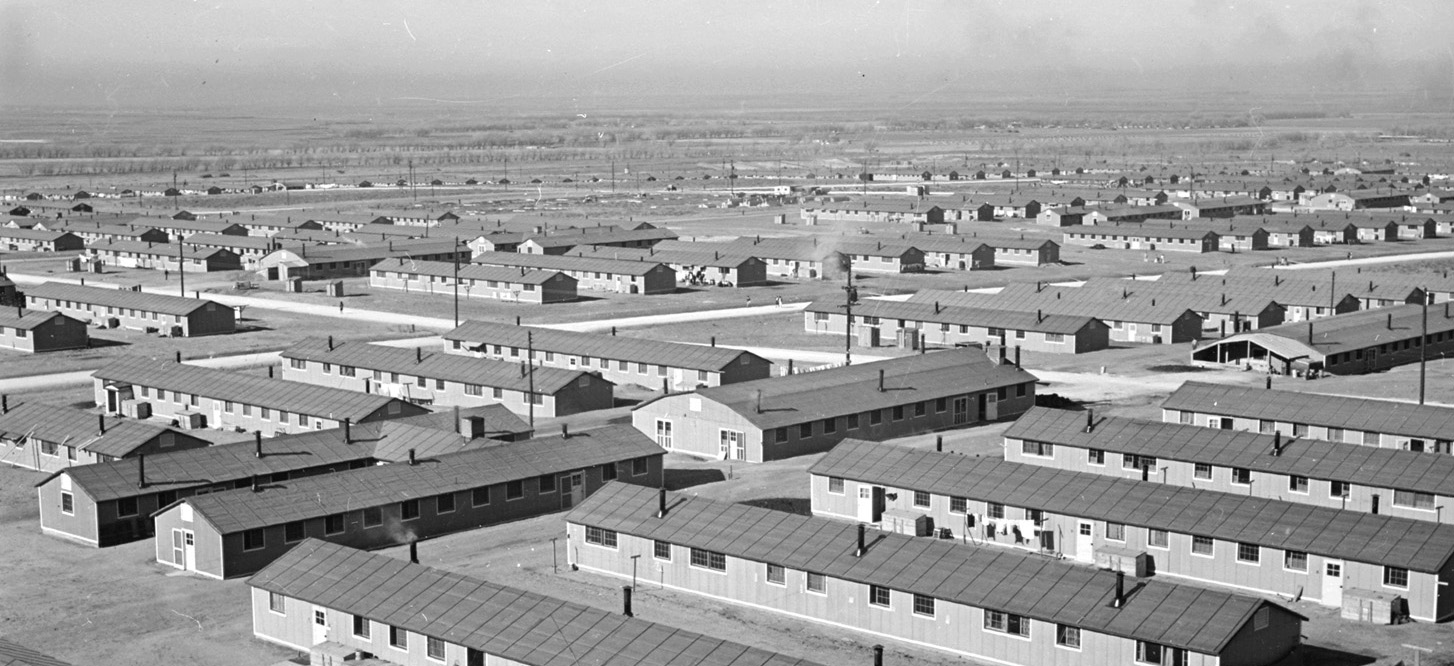

With the basic plan created, training and rehearsals followed. Since the two Ranger battalions were to be attached to the 1st Infantry Division for the Gela operation, they left their training areas in Algeria’s Atlas Mountains to join the division a few miles west of the city of Algiers. There, they practiced for the amphibious assault using mock-ups of the primary objectives around Gela. Luckily, planners had the foresight to assign the same Navy landing craft personnel and shore parties who would be with the Rangers for the actual mission. The soldiers and sailors were thus able to train with their actual counterparts, which later helped immensely in dealing with the myriad problems that arose not only in training, but also during the actual invasion.

Two full-scale practice landings were carried out, including live fire from the naval support ships offshore. Overall, the training went well with one exception: the submarine that would guide them ashore was not present. Darby and his fellow leaders worried the absence would cause problems in coordination during the real landing.

“Follow Me”

On June 30, 1943, the bulk of Force X boarded ships in Algiers harbor to begin its journey to Sicily. First was a stop in Bizerte, Tunisia, a few hundred miles east of Algiers. There, Force X joined other embarked American troops for the voyage to their objective. They quickly crossed the short distance to Sicily, but on the night of July 9 nature interrupted their efforts. A fierce storm blew in, waves battering the hulls of the invasion fleet. Many soldiers, unused to enduring such weather at sea, were overcome with seasickness, and staff officers feared the gale’s effect on the planned landings.

Meteorologists forecasted better conditions for the coming day, however, so the operation continued as planned. As predicted, the foul weather abated and Operation Husky began.

With beaches ahead in the gloomy darkness, the Rangers began loading themselves into the landing craft from their two transports, the HMS Albert and Charles and the USS Dickman. Aboard the Dickman, the tune “American Patrol” by Glenn Miller’s band rang out from the speakers. One by one, the landing craft pushed away from the transports and began circling, waiting for the submarine that would lead them to Gela. Time passed and it did not appear, just as some had feared during training.

Luckily, a naval officer from the third wave took the initiative to get the assault moving. He and Darby worked together to get the boats into proper formation and moving toward shore. True to form, Darby had his boat move among the group, telling his Rangers to “follow me.” Soon they were headed toward Gela.

Two Boats Capsized

As the assault waves drew closer to the beach, the chaos of battle set in. Italian defenders switched on powerful searchlights, plying them across the water seeking out the invaders. The vulnerable landing craft would be easy targets for the guns ashore, but two U.S. ships, the cruiser Savannah and the destroyer Shubrick, responded quickly, knocking out the lights. Frank Krall, a sailor aboard the Shubrick, kept a journal. Part of his entry for July 10, 1943, read simply: “0300. All guns in automatic. We just fired two shots at searchlight. It went out promptly.”

A lack of illumination did not stop the Italians from pouring fire seaward. Machine-gun fire swept over the waves and mortar bombs plunged into the water, seeking out the vulnerable Rangers in their thin-skinned boats. Several Americans returned fire with rockets from their bazookas. As the first wave closed with the shoreline a massive explosion shattered the night air; under orders from General Alfredo Guzzoni, the Italian officer commanding all forces on Sicily, local troops had destroyed the landmark pier jutting out from the middle of Gela to deny its use to the attackers. Debris from the explosion peppered the town and the water around the approaching Rangers.

Tragic confusion reigned when one of the assault boats struck a sandbar some distance from shore. The collision was at a sharp angle, and the boat began to capsize, flipping over into the murky waters. The Rangers aboard began jumping into the surf, thinking they were close enough for the depth to be shallow and thus able to wade the rest of the way. Unfortunately, it was still deep and Lieutenant Joseph Zagata and 16 of his men from E Company drowned. Some of the other landing craft stopped to render aid.

Nearby, a landing craft carrying soldiers of B Company, 39th Engineers, also ran into trouble. It took a direct hit that immediately caused torrents of water to flood into the damaged boat. Within moments the landing craft capsized, taking everyone aboard into the water. This time, fortune smiled; all but one of the soldiers could swim and got to safety. The hapless nonswimmer was saved by the company medical officer, Lieutenant Albert Thompson, who grabbed the soldier and pulled him along.

Heroism on the Beaches

Arriving at about 0335, both Ranger battalions rushed onto a beach strewn with mines and barbed wire. The fishing boats seen in the aerial images were in fact unusable wrecks. Immediately, they began moving forward, alternately crawling and rushing. The commander of D Company, 4th Rangers, Lieutenant Bernard Wojciak, was leading his soldiers forward when he stepped on a mine. The snarling explosion tore open the young officer’s chest. He collapsed next to his first sergeant, Randall Harris, telling him, “I’ve had it, Harry.” Harris recalled he could see Wojciak’s heart beating in the wreckage of his torso before he died.

All the other officers in D Company quickly became casualties as well. The NCO found himself leading the company. He moved forward again only to set off another mine. This one blasted his legs and stomach. Despite his wounds, Harris moved up to a group of pillboxes overlooking the beach and silenced them with some hand grenades. Only then did he pause to dust his wounds with his packet of sulfa powder and adjust his belt to hold in his now-protruding intestines. He led his Rangers for two more hours until he felt the job was done; only then did he walk back down to the beach in search of the medics. This act of selflessness earned him a battlefield commission and an award of the Distinguished Service Cross, America’s second highest decoration for valor.

Fighting House-to-House in Gela

Moving in from the beach, the Rangers began a slogging, house-to-house fight for Gela itself. Companies A and B moved toward their assigned objectives, two shore batteries and a mortar position at the northwest edge of town. Captain James Lyle was in joint command of the two units. He told his men that if they wanted to be alive tomorrow, they had better shoot everything they saw today.

Wary, they moved down the streets with columns on each side, ready to cover each other against attack from ahead or above. The first sergeant from Company A spotted a group of four Italians running toward a bunker built to block a road. The muzzles of a 47mm antitank gun and two machine guns protruded menacingly from its embrasures. Acting quickly, the American ran after the Italians and caught them just as the last man was trying to close the bunker’s door. With a heavy kick, the first sergeant forced the door back open and sprayed the interior with his Thompson submachine gun before tossing in a hand grenade.

Elsewhere, a small group of Italians made a stand in a cathedral near the town square in the 4th Rangers’ area. The Americans went after them, engaging in a vicious firefight among the pews. The last Italians died clustered around the altar. In the 1st Ranger zone, Captain Lyle could not call upon the chemical mortar unit landing behind him; the necessary radio had been dropped into the ocean during the confusion of landing.

The first gun position was surrounded by wire. The Rangers crawled up a ditch to get close, blew the wire with explosives and rushed the Italians, throwing grenades as they went. The position fell quickly, and three 77mm field guns fell into their hands. The sights were missing, but several of the Rangers were former artillerymen and quickly formed a gun battery. The nearby enemy mortar platoon was likewise dispatched with grenades and small arms fire.

The engineers were also meeting their share of enemy resistance. As the 39th’s A and B Companies began to move off the beach a pair of bunkers opened a murderous machine-gun fire, pinning both companies down. After a harrowing few minutes, Sergeant Harold Gilbert of Company B decided to take action. He sprinted to the closest bunker and threw in a grenade. The dull crump of the explosion was enough to silence both enemy positions; the other bunker’s occupants decided to surrender after seeing what happened to their comrades. They poked a white flag out of their tiny fortification, and eight Italians were led into captivity by Sergeant Gilbert. The engineers met only slight additional resistance until Gela was taken a few hours later. Aside from a few snipers, many of the remaining bunkers capitulated without a shot fired.

Several hours had now passed since the landing. The 1st Rangers set up their battalion headquarters near a schoolhouse that turned out to be full of Italian soldiers. Machine-gun fire pelted the Americans as they scrambled to mount a counterattack. Darby and his driver, Carlo Contrera, joined the Rangers against the schoolhouse. Darby noticed Contrera was shaking and asked if he was scared. The young driver casually retorted, “No, sir. I’m just shaking with patriotism.” The assault on the schoolhouse succeeded, and over 50 Italians were taken prisoner.

Gela Captured

By 0800 Gela was firmly in American hands. Both Ranger battalions had penetrated to the edge of town and were weaving their lines into those of the 1st Infantry Division troops landing on their flanks. The 39th Engineers were ashore and with them the 83rd Chemical Mortar Battalion was digging in and getting ready to provide fire support, though the mortarmen were having trouble getting the two-wheeled carts carrying their weapons and equipment over the soft sand.

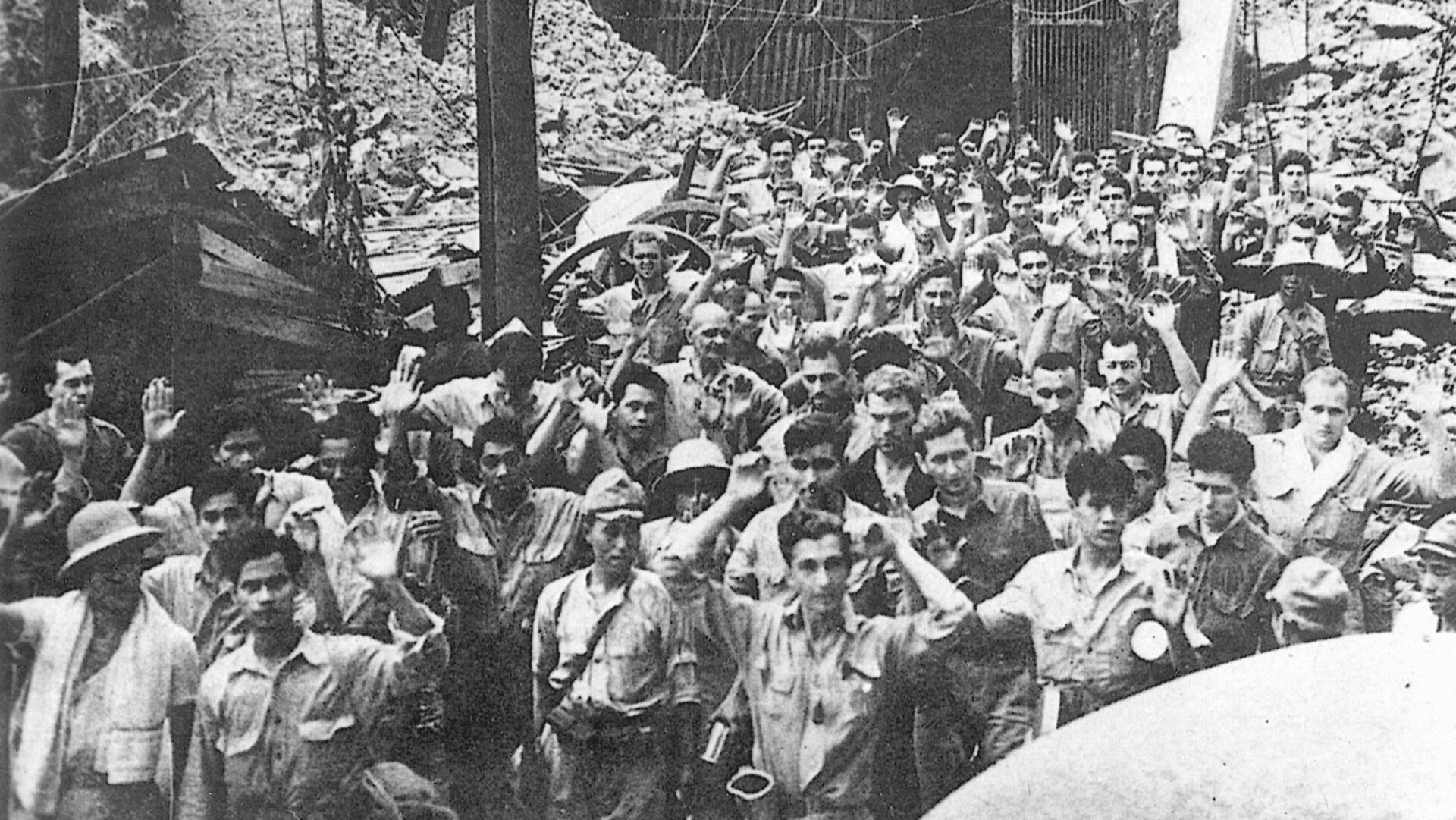

The engineers set up a temporary prisoner of war pen made of wire, but it quickly filled to capacity. Before long over 200 Italian POWs had arrived, more than the pen could hold. The Americans had no choice but to allow some of them to stay outside the wire. It made little difference; the Italians were not inclined to make trouble or try to escape. Some seemed quite content to eat American C-rations and await evacuation.

In just a few short hours Gela had been seized. The initial resistance was spotty and had allowed Force X to quickly overwhelm the defenders. This fast assault was about to pay dividends, for the Italians and Germans had wasted little time preparing their riposte against the landings. Despite Allied distraction attempts elsewhere, General Guzzoni had realized where his enemy’s main effort was falling and ordered his troops to respond appropriately. Italian infantry and armor were moving toward Gela by mid-morning, with elements of the German Hermann Göring Division not far behind.

Renault Tanks of the Italian Army

The first Italians to move on Gela set out from Niscemi, roughly eight miles northeast. Some 32 light tanks reinforced with infantry moved south on the main road. The tanks were actually French Renaults captured during the German invasion of France and subsequently passed on to the Italians to bolster their comparatively weak armored forces. By mid-1943 the Renaults were hopelessly obsolete, but at this early stage in Operation Husky there were no Allied tank forces to oppose them. The Renaults could still make themselves felt supporting Italian infantry against Force X, a lightly equipped, infantry-heavy unit.

The Italian unit found its work cut out for it, however. As they moved down the road to Gela a 100-strong contingent of paratroopers from the 82nd Airborne Division attacked them from a house they had fortified.

Further punishment came screaming in from the USS Boise. The light cruiser’s 15 six-inch guns were equivalent to more than a battalion of 155mm howitzers. The heavy shells crashed around the Italian tanks, sending heavy chunks of shrapnel tearing through the air and into the Italian troops. Many of the Renaults were knocked out as well, too light to withstand such heavy fire.

Still, perhaps 20 Italian tanks kept going toward Gela, racing through all the Americans could throw at them. It was a brave act, but the remaining tanks were now even more vulnerable, for the Italian infantry was stopped, leaving its armor unsupported. They blundered into an area defended by the 1st Division’s 16th Infantry. The Americans poured fire against the Italian tanks, inflicting heavy casualties and stopping them cold. The remainder withdrew to the north.

A short time later a second force of 24 Renaults appeared on Highway 117, approaching from the nearby Ponte Olivo airfield. Once again the destroyer Shubrick went into action, firing repeated salvos of 5-inch shells at the desperate Italian force. Over half the enemy tanks were stopped, many of them burning along the roadway, but 10 of them continued toward Gela. Captain James Lyle of the 1st Rangers reported four of them stopped in a grove of trees while the remainder continued into the town itself. These tanks were without infantry support and had just entered a town filled with aggressive, offensive-minded Rangers.

Infantry vs Armor

The battle against the tanks quickly turned into a swirling melee. Rangers climbed to rooftops and dropped grenades and satchel charges. Captain Jack Street put together 15-pound charges of high explosives and dropped them from his rooftop vantage point. Other Rangers ducked through alleys and behind stone walls to strike at the Italian armor with bazookas and more explosives.

The tanks moved toward Gela’s central piazza, and Darby raced to the area in his jeep. While Contrera drove the jeep into alleys and side streets to make them a difficult target, Darby manned the jeep’s .30-caliber machine gun and fired bursts at the tanks whenever he could. Even the Renault’s thin armor was proof against mere bullets, however, so the resourceful Darby directed Contrera back to the beach. There, El Darbo commandeered a 37mm antitank gun recently brought ashore. A sealed crate of ammunition sat nearby. Seizing an axe, Darby smashed it open and grabbed a metal box of armor-piercing ammunition.

Hitching the gun onto their jeep, Darby and Contrera rushed back to the fighting, where Captain Charles Shunstrom joined them. As they hurriedly set up the cannon, an Italian tank rumbled around a corner and advanced on them. Darby jumped onto the jeep and let loose two bursts from his machine gun, but they had no effect. In return, the Italian tankers fired two shells at the American officers. Both rounds went high, exploding against the building behind them in a crash of dust and masonry. Darby jumped off the jeep and loaded a shell into the breech of the 37mm gun. Shunstrom peered through the sights and took aim. The round struck the Renault’s turret.

Without hesitation, Darby threw another round into the gun’s breech, and Shunstrom fired again. This round struck the hull, and the tank was actually sent backward about three feet as a sheet of flame rolled over it, though the tank did not apparently remain afire. Darby went over to the Renault and set a thermite grenade on one of the hatches. As the grenade heated up the metal, the screaming crew leaped out with hands up in surrender.

Some of the engineers joined in on the tank hunt. Lieutenant Dee Baker of B Company/39th led a squad of men against another Renault, pelting its tracks and road wheels with rifle grenades and bazooka rockets until it was immobilized. More rockets and grenades destroyed the tank. After this victory the engineers repeated their feat on a second tank. The remaining tank crews decided they had taken enough, pulled back, and retreated out of town. The four tanks in the grove were fired on by 4.2-inch mortars at the direction of Captain Lyle. One was knocked out, and the rest fled north, a column of black smoke wafting from the wrecked tank.

“Kentucky Windage”

The Italians still had a few units left to throw at the Americans. One was a group of infantry. Perhaps unaware of the invaders’ exact location, they came striding in from the west in a marching column more suited to the parade field than a tactical formation. Well-place mortar and naval gunfire crashed around them, killing and wounding many and driving the rest away in a disorganized rout.

Yet another group of tanks appeared and drove toward the 1st Rangers’ area. Captain Lyle now called in his three-piece artillery battery, the Italian guns manned by Rangers. Another Ranger was situated in front of the advancing tanks in an observation post directly between the American guns and the enemy armor. He called in a fire mission. The Ranger gun crews took careful aim and let fly a salvo, which landed directly on the observation post. The observer replied with a stream of curses as the gun crews quickly elevated their tubes.

Afterward, the cannon were quickly sighted in using “Kentucky Windage” and the tanks were driven back. To the Americans’ surprise, their artillery fire also caused the retreat of a previously unseen company of Italian infantry who were well concealed around a farmhouse. Apparently thinking they had been spotted, the Italians fled along with their tanks.

Clearing the Minefield

By late morning a lull in ground action ensued. The Hermann Göring Division was having problems assembling its tanks and infantry together for a coordinated attack. The Italian attacks had come in piecemeal and were repulsed relatively easily. The German commander had no wish to make the same error. Action continued offshore and in the air, however.

Lieutenant John Pacer of the 39th Engineers was charged with seeing to the unloading of the LSTs (Landing Ship, Tank) carrying the battalion’s equipment and vehicles. When the Gela pier was destroyed these ships were diverted to a beach in the 1st Infantry Division’s landing zone. He set off to find them but the mass confusion had turned the beach into a parking lot of jammed vehicles and piles of supplies. Pacer finally found one of his ships, LST 388, which carried some of the battalion’s M2 half-tracks. As he worked to get the needed vehicles unloaded, a trio of German Messerschmitt Me-109 fighters appeared overhead. Two bombs straddled the LST, unleashing a torrent of blast and fragments. Pacer escaped injury but was shaken for a few minutes. Finally, he got his half-tracks unloaded only to have them get stuck in the sand mere yards from the LST.

Another engineer officer, Captain Harold Hansen of Company A, had worked all morning to clear mines from the beach. A group of tanks waited in a nearby LST, unable to disembark for fear of the minefields the planners had not counted on. The unit’s mine detectors were loaded aboard another LST and could not be found. Hansen had no choice but to order the slow, tedious process of clearing the mines with bayonets. When the Italian armored attack began later in the morning, Hansen realized they would have to accept some risk to get the American tanks into the fight.

He and his men began checking the placement of the mines they had found, looking for a pattern in how they were laid. After a short while a regular pattern was indeed found. Measuring the distance between the mines, Hansen had his engineers pace off that distance and check for mines at the expected intervals. The plan worked; the Italians had laid their minefields in the same pattern over and again. All the mines were marked and removed without any casualties. Another area of beach turned out to be blissfully empty of mines because the locals who were ordered to plant them quit after two of them were blown up in the attempt.

The Luftwaffe Strikes

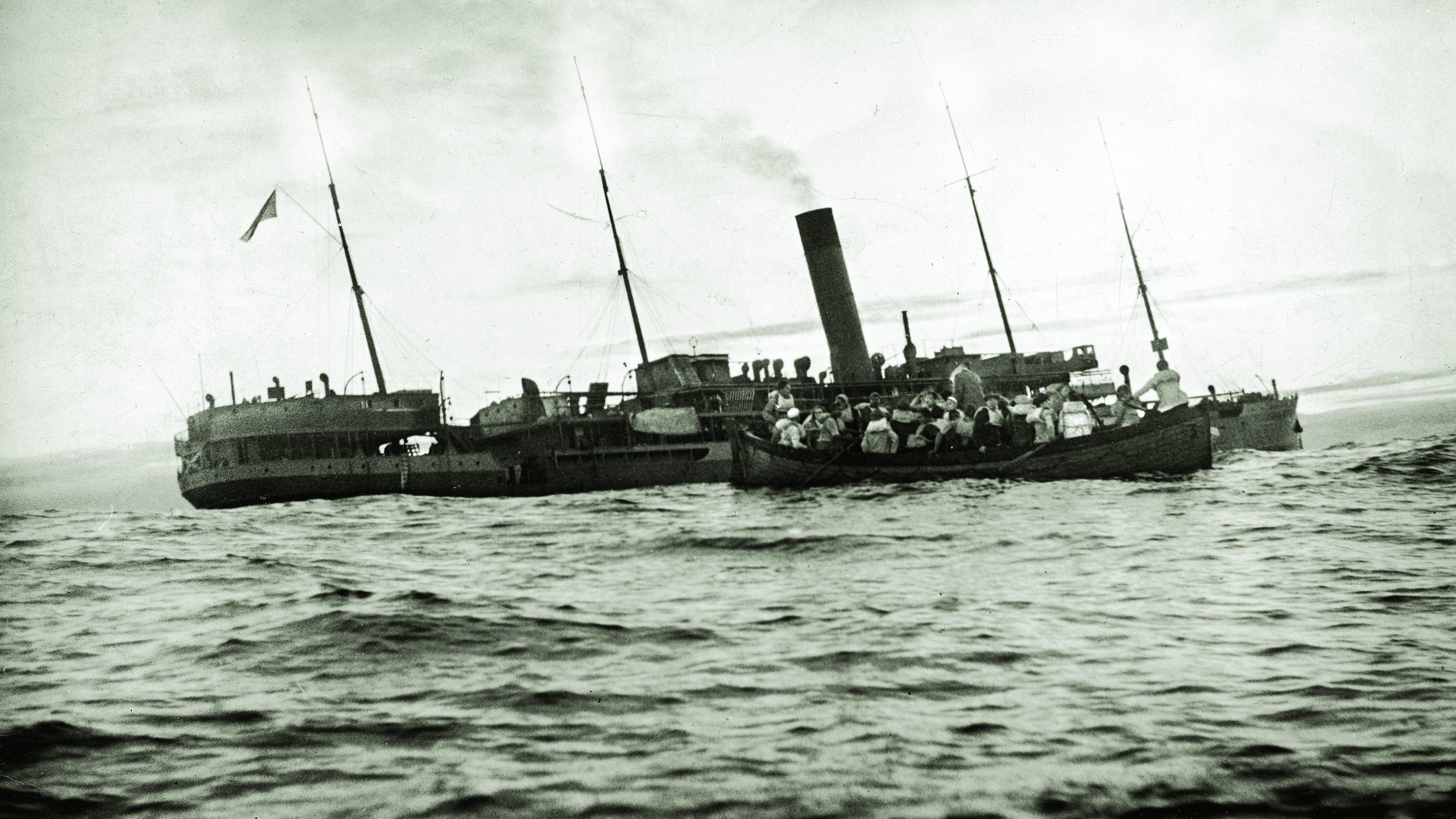

As the engineers worked to clear the beaches and unload their equipment, the Rangers dug in and prepared for the expected counterattacks. While they did so, the battlefield remained mostly quiet. The same could not be said offshore. The naval battle off Gela began just as dawn crept over the eastern horizon. A squadron of Luftwaffe planes appeared at 0458 and quickly spotted the destroyer USS Maddox. The American ship was on antisubmarine patrol some 16 miles offshore.

One of the German planes dove on the hapless destroyer, which responded with its antiaircraft guns as the aircraft released a bomb. The projectile exploded by the ship’s starboard stern, wrecking the entire stern and probably causing the aft magazine to explode.

An officer on another ship noted: “A great blob of light bleached and reddened the sky … followed by a blast more sullen and deafening than any we have so far heard.” Two minutes later Maddox was gone along with 211 of her crew. The tug Intent later rescued 74 survivors.

For the rest of the afternoon occasional Axis air attacks took place against the naval forces offshore. Only the destroyer Murphy received minor damage. Several cruisers launched their seaplanes to provide scouting and fire direction. Repeated attacks by Me-109s drove them back or shot them down, though not before some of them provided timely data on the Italian tank movements, allowing the ships to fire on them. They also helped the cruisers to concentrate on nearby shore batteries before they were used up by early afternoon. By 1320 the Shubrick alone had fired over 500 rounds of 5-inch ammunition.

A few more attacks came in against the transports and LSTs, which were having a hard time unloading after the destruction of the Gela pier. General Allen sent an urgent request for tanks and artillery to be offloaded. After the Italian counterattacks there was concern about what would come next. The extensive confusion only delayed the process.

At 1835 another Me-109 appeared, flying out of the setting sun. The pilot chose LST 313 as its target. Its bomb exploded under the tank deck and started a huge fire, which engulfed the ship. Soldiers and sailors swam out to the stricken ship to help wounded off its bow ramp. The captain of LST 311, Lieutenant Robert L. Coleman, pulled his ship around so his bow connected with the stern of LST 313. This allowed 80 trapped men to escape the flames. Still, 21 were lost.

“They can’t hit me!”

Darkness removed the threat of further air attack, but the situation was still full of tension. There were scant hours until a new dawn brought renewed combat. More Axis armor was sure to hit the beachhead, and continued air attacks were a certainty. Allied fighter cover had been scant and ineffective due to problems in coordination and inexperienced air support liaisons. There was no promise of anything better the next day. All that could be done was to continue trying to offload tanks, artillery, and other equipment and get it all into action against the enemy. The crews and shore parties had been working all day and were exhausted. Some dropped to sleep wherever they were; others continued their struggle to reinforce their comrades throughout the night.

With the sunrise came a further rash of air attacks. At 0635 a dozen Italian bombers appeared over the invasion beaches. They concentrated on the transports but had little luck after the ships scattered in all directions. Axis planes would continue their raids all day and into the next night.

The fears about a renewed armor attack in the morning were well founded. By 0640 on July 11, over a dozen German tanks were met by American infantry of the 26th Regiment, 1st Division, as they advanced north toward Ponte Olivo airfield. Other German forces were advancing from the area of Niscemi and from Biscari, east of Gela. An Italian force from the Livorno Division was also spotted advancing on Gela from the northwest.

The tanks moving against the 26th Infantry left the road and set out across the wheat fields separating them from the beachhead. Observing their advance was Brig. Gen. Theodore “Ted” Roosevelt, assistant division commander of the 1st Infantry Division. Son of famed President Teddy Roosevelt, he had come forward to observe conditions on the battlefield just in time to see the Hermann Göring Division arrive. The German tankers knew their business and immediately pressed the Americans. Two PzKpfw. IV tanks moved across open ground at high speed, trying to draw the fire of any opposing tanks or guns in the area. The rest advanced in short bursts, sprinting from one fold in the terrain to another, making themselves difficult targets while ready to fire on anything that revealed itself.

Roosevelt called back to the division command post for support, especially tanks. The infantry had little to throw at the enemy armor, which infiltrated into the 3rd Battalion, 26th’s rear areas while the 2nd Battalion, following, tried to plug the gaps. The tanks were still unavailable, however, and the infantrymen were gradually pushed back until they were forming hasty defensive lines on the outskirts of Gela itself.

Roosevelt called back again, telling Allen, “Situation not so good.” Undaunted, Roosevelt bolstered his men by walking along the American lines aided by his trusty cane, in full view of the enemy, bragging, “They can’t hit me!”

George S. Patton Joins the Fight

To the east, the 16th Regiment’s 2nd Battalion was attacked by a force including 40 tanks. After a stiff fight the Germans pushed them back to Piano Lupo, seven or eight miles east of Gela on Highway 115, the coastal road. By 1010 German tanks had appeared at the crossroads connecting Gela and Niscemi. The regimental antitank company, still equipped with the obsolete 37mm cannon, had lost two-thirds of its guns. One of the battalion commanders was killed while personally manning one of the weapons. By 1030 many of the infantrymen were fleeing in retreat past artillery pieces that were firing at the pursuing Germans less than a mile behind. Still no American tanks appeared.

Despite their apparent success, the German had problems of their own. One regiment of infantry had gotten lost overnight and was not in position to support the dawn armored thrust. Many of the fearsome Tiger tanks were breaking down along the road, blocking it since there were no recovery vehicles that could move them. Communication with the Italians had completely broken down. While the Livorno Division had been ordered to attack Gela as well, the Hermann Göring Division did not know it. Confusion reigned on both sides, but neither could do more than to keep fighting, keep feeding men and machines into the struggle.

Northwest of Gela, the Italians were indeed attacking. Tanks and infantry were only a mile from the town. Darby and his Rangers were defending, but they were hard pressed. Despite heavy fire from the chemical mortars, the enemy continued to advance.

Captain Lyle was directing his men when General George Patton, the Seventh Army commander, appeared behind him. Patton had come ashore to see how the fighting was progressing and immediately immersed himself in the action. After admonishing the young Ranger for having an unbuckled chinstrap, Patton was briefed by Lyle. Patton told him: “Kill every one of the …. bastards!” before leaving.

Patton also came across a naval gunfire liaison officer in Gela and told him to get some fire on the advancing Italians. The sailor wasted no time; within minutes salvos of six-inch shells from the cruiser Boise were crashing all around the Livorno soldiers. White phosphorous bombs from the mortars raised clouds of burning smoke, causing panic and retreat among the survivors. One Ranger officer recalled seeing the bodies of Italian infantry hanging from the branches of trees. The Italian portion of the attack had been stopped.

Armored Reconnaissance

Captain Hanson, who had discovered the pattern in the Italian minefields, now showed up in Gela with a few half-tracks that managed to get off the beach. Patton immediately ordered him to scout out the Italian positions outside Gela. Hanson took four men and one half-track and started up the road. Almost immediately they stumbled into a group of Italians hiding in a gully. A sharp firefight ensued where the half-track’s .50-caliber machine gun saw good use. Continuing forward, the vehicle took a hit from an antitank gun, forcing them to fall back. Hanson told Patton the enemy was disorganized but digging in.

A second reconnaissance mission was dispatched with three half-tracks and a pair of M4 Sherman tanks. This group attempted to flank the Italian position and ran into an enemy field hospital. When the Americans stopped to question the hospital personnel, a large number of Italian soldiers surrendered, unwilling to endure more of the hellish bombardment they had received. The patrol returned to American lines with a long ragged line of 450 Italian prisoners following.

All morning naval gunfire poured forth from the destroyers and cruisers offshore. The Shubrick and its compatriot Jeffers, having exhausted almost all their ammunition the day before, were replaced by two destroyers, Glennon and Butler. The cruisers Savannah and Boise remained on station, ready to rain six-inch shells wherever needed. On July 11, the struggle for Gela was as much a naval battle as a ground one. The U.S. Navy would not disappoint the American soldiers ashore this day.

Driving Off the German Armor

By 1100 the situation was at its most critical. Though the Italians to the west were no longer attacking, the Germans were still pressing hard. German artillery and tanks were able to fire on the beaches and Gela, and their infantry was getting so close even Navy personnel in shore parties armed themselves with rifles. From Patton’s command post in town, he saw Italian civilians running to and fro in panicked frenzy as 88mm shells landed. He sent MPs to restore order, using rifle butts when necessary.

At times the two sides were so closely intermingled the ships offshore could not shoot for fear of fratricide. Finally, with 14 of their tanks burning or destroyed, the Germans nearest Gela began falling back. With some distance between the two combatants, the Navy was able to join in again. Hundreds of 5- and 6-inch rounds peppered the retreating Germans, continuing for several hours.

East of Gela the 16th Regiment gave orders no one was to fall back. Troops could take cover from tanks but were told to push back anything else that came near. Many fought as isolated groups in small, desperate struggles. Soon only two of the regiment’s antitank guns were still operational. Finally, help arrived shortly after noon. The regimental cannon company got its weapons off the crowded beaches and went into action.

Joining them were a handful of Sherman tanks, which quickly added their firepower to the battle against the Germans. Following them were several more battalions of artillery. The crews of one “Long Tom” 155mm battery fired directly at approaching German tanks. A lieutenant walked along the gun line, pistol in hand, threatening to shoot anyone who ran.

Again the Navy plunged into the action. One of the cruisers came in so close her sailors had to take constant depth readings to ensure the ship did not run aground. Both Boise and Savannah, joined by four destroyers, savaged the Germans. Boise’s shells carried variable time fuses that caused them to detonate in deadly airbursts above their targets. Trees were shredded, grapevines torn apart, wheat fields ripped away. Amid all this devastation, human flesh was only too vulnerable, and German soldiers were killed and wounded in scores.

Within minutes over a dozen German tanks were reduced to wreckage. American soldiers could actually hear the screams of tank crewmen trapped in the fires of their burning vehicles. It was an eerie and disturbing sound, ending when the tank’s ammunition detonated from the heat, killing anyone left inside. At 1316 an observer called for naval gunfire against a group of German tanks trying to regroup for another attack. The destroyer Butler responded with 48 rounds. One of the heavy Tigers was hit on the turret by a shell, though it is unknown whether it was naval gunfire or Army artillery. The round did not penetrate the Tiger’s thick armor, but the tank’s commander recalled how rivets inside the behemoth broke off and flew around the compartment.

“Running to the Rear Hysterically Crying”

Around 1400, the Hermann Göring Division commander, General Paul Conrath, called off the attack. German troops and tanks pulled back gradually, chased by artillery and naval shells. One German officer planted a story with some Sicilian farmers he passed, hoping to discourage American pursuit. “Naval gunfire forced us to withdraw, but if the Allies pursue too far inland they will be engaged by superior German forces and destroyed!”

It was a weak bluff; in reality, some of the defeated German troops had discarded or abandoned their equipment and according to the U.S. 16th Regiment’s journal, were “running to the rear hysterically crying.” Nearly half their armored strength had been lost.

At 1545 another air raid struck. This time the transport Robert Rowan was targeted. It was hit, and fires started aboard the hapless ship, which was loaded with ammunition. The ship burned until about 1700 when the load of ordnance finally exploded after the crew had abandoned her. The enormous explosion raised a huge cloud of smoke into the air, tossing pieces of the ship around the landing area. The Robert Rowan settled in shallow water where she burned into the night, providing a beacon for further air raids.

The battered Italians tried another sortie at 1700 that afternoon, an infantry force coming down from the town of Butera to the northwest. The advancing Axis troops ran into the Rangers who, assisted by salvos from the Savannah, turned away this last effort without much difficulty. Other ships fired on troop or vehicle concentrations until 2057, when the shore party controlling a 165-round barrage by USS Glennon signaled, “Cease fire, good shooting!” Sporadic fighting continued until darkness fell over the battlefield, bringing weary soldiers and sailors a welcome breather.

The battle for Gela was essentially over; the morning of July 12 would see American troops take the offensive, advancing on the Ponte Olivo airfield, Butera, and other objectives inland. The battle had been a close-run thing. At times the Germans had been close to reaching the invasion beaches, but never quite got there thanks to dogged American infantry, the firepower of the U.S. Navy, and the gunners of the artillery.

Savannah, Boise, and the seven accompanying destroyers offshore had fired 3,766 rounds of 5- and 6-inch ammunition on July 10-11, 1943. Overall it was a stellar example of a joint operation, Army and Navy assets working together. Soldiers, including Patton, who doubted the utility of naval gunfire support, had a change of heart. In this regard Gela was a harbinger of how amphibious assaults would occur in the future at places such as Salerno, Anzio, and Normandy.

Losing the ‘Battle of the Bakery’

Those actions were for another day, however. At Gela there was one more battle to be fought. Ranger Sergeant Marcell Swank was assigned the duty of guarding a bakery in Gela. Run by a Polish baker, the facility had been commandeered by the U.S. Army to make bread for the hungry troops. As the Pole went about his work, the warm smell of fresh loaves no doubt wafted down the street, attracting the attention of a number of nearby Sicilian women. Soon a crowd of them gathered outside the bakery, shouting for a portion of the bread. They had children to feed, they protested, hungry and ragged from the battle that had swirled around the town’s civilians.

Sergeant Swank refused them access; he had his orders. The women retired across the street, muttering. After conferring among themselves, they turned from a crowd into a mob, advancing in a group toward the bakery. Swank responded by pointing his Thompson submachine gun into the air and rattling off a sharp burst. The Sicilian women quickly retreated to the other side of the street, but they were not afraid to make a number of rude gestures and hurl insults and curses at the perturbed Ranger.

Minutes later the mob advanced again to be greeted by another burst over their heads. Again the women stopped, but in the middle of the street this time. Apparently some of them sized up the young sergeant and decided he would not likely gun down a horde of hungry ladies, so they went forward a third time and now nothing would stop them. The women rushed into the bakery. Sergeant Swank and the baker ran away. The Rangers won the battle for Gela but lost the Battle of the Bakery.

Superb; thank you.