By David Lippman

“I am busy getting ready for the next battle,” Field Marshal Sir Bernard Law Montgomery wrote his son David in early March 1945. This was just weeks before the start of Operation Plunder, which involved the allies finally crossing the Rhine into German territory. “The Rhine is some river,” Montgomery said in his letter, “but we shall get over it.”

The Rhine was more than a river. It was a sacred waterway to the Germans, the source of most of their legends and myths. And at this stage in the war, crossing the Rhine was the last barrier between the advancing Allied armies and the conquest of Germany. If the Germans could hold their beloved river, they might be able to stand off the Allies.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, supreme Allied commander in Europe, had chosen to advance on Germany on a broad front, but the main axis of advance would be in the north, to pinch off and surround the Ruhr, Germany’s industrial heartland. The primary advance of Operation Plunder was to be led by Montgomery’s 21st Army Group, which consisted of the 1st Canadian Army, the 2nd British Army, and the 9th U.S. Army, by now all veterans of hard campaigns.

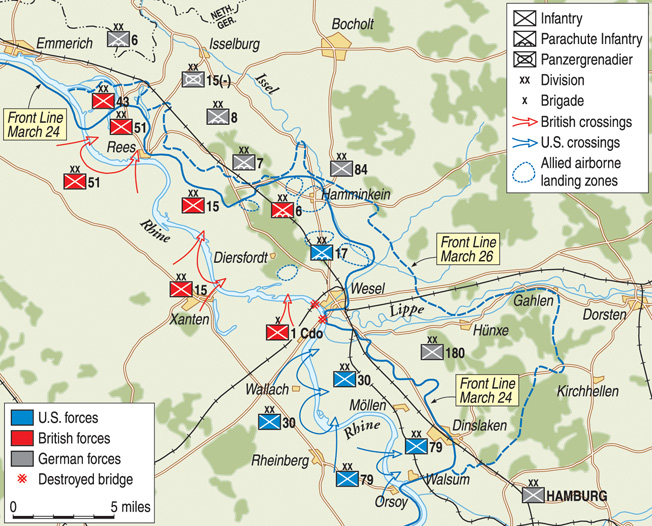

Monty’s original plan called for the British 2nd Army to launch the main assault at three places: Rees, 25 miles upstream from Arnhem; near Xanten, seven miles upstream and close to Wesel; and at Rheinberg, 16 miles farther upstream at the northwest corner of the Ruhr. The U.S. 9th Army commander, Lt. Gen. William Simpson, and the 1st Canadian Army’s boss, General Harry Crerar, both objected.

After some back and forth between the three commanders and staffs, Montgomery agreed to include the 9th Army in the initial assault as well as the 9th Canadian Brigade, veterans of Normandy. The 9th Army took over the Rheinberg crossing.

What made Crossing the Rhine the Greatest Assault River Crossing of All Time

Montgomery’s preparations for the attack across the Rhine, code-named Operation Plunder, were described as elephantine. With 1.2 million men under his command, Montgomery was launching the greatest assault river crossing of all time.

The Rhine was 400 yards wide at the Wesel crossing point, and to defeat the river and the heavy German fortifications, the 2nd Army alone collected 60,000 tons of ammunition, 30,000 tons of engineer stores, and 28,000 tons of above normal daily requirements. The 9th Army stockpiled 138,000 tons for the crossings. More than 37,000 British and 22,000 American engineers would participate in the assault, along with 5,500 artillery pieces, antitank and antiaircraft guns, and rocket projectors.

Preparations were elaborate. Montgomery would leave little to chance. The invading armies were elaborately camouflaged. A world record 66-mile-long smoke screen along the western side of the Rhine concealed preparations. Dummy installations were created to fool German intelligence. Coordinated patrols and artillery fire added to the deception measures. Civilians were evacuated from their homes for several miles west of the Rhine. Railheads were pushed forward, and new roads were built. The 9th Army would issue more than 800,000 maps.

Above all, Montgomery would not be hurried. Even though two American Rhine crossings preceded his main effort, Montgomery rightly observed that the Germans would fight hard for their sacred river, and his troops needed heavy training for the attack. Major John Graham, who commanded an infantry company in the 2nd Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders, noted that many British troops were raw recruits, drawn from training establishments by the shortage of manpower.

“Our men were not sufficiently well trained at this stage in the campaign to be able to exploit against the professional German soldier in a hasty impromptu crossing,” he said. “We couldn’t overcome the shortage of leaders. By that time in the war the experienced corporals and sergeants had disappeared, been killed, and we were left with people who were really privates who had been promoted. (It still seems absurd that I was 21 and a major). I think it would have been a pretty unwise commander who launched them into battle without the most thorough preparations.”

Germany’s Defenses

The Germans were also preparing. The only strategy Adolf Hitler had on the Western Front since the failure of the Ardennes offensive of December 1944 was to hold the line, and to do so he brought in Luftwaffe Field Marshal Albert “Smiling Al” Kesselring to take over the front.

Kesselring, despite his Luftwaffe background, had made a name for himself commanding the German defenses in Italy, which had exacted a massive price while withdrawing slowly up the boot.

On March 11, Kesselring met with the top subordinates who would defend against Monty’s assault, Colonel General Johannes Blaskowitz, who commanded Army Group H, and General Alfred Schlemm, the tough paratrooper who commanded 1st Parachute Army near Wesel.

Despite taking heavy losses on the eastern bank of the Rhine, Schlemm assured his superiors that 1st Parachute Army was ready to hold the Rhine. He reported, “First Parachute Army succeeded in withdrawing all of its supply elements in orderly fashion, saving almost all its artillery and withdrawing enough troops so that a new defensive front [can] be built up on the east bank.” Schlemm guessed correctly that the focal points of an Allied attack across the Rhine would be at Emmerich and Rees and that there would be an airborne assault as well.

To defend against these threats, Schlemm strengthened his antiaircraft defenses near Wesel, with 814 heavy and light guns and mobile anti-airborne forces covering all the likely drop zones. Gunners had to sleep fully clothed at their posts.

Mixed Units of Veterans and Militia

Schlemm disposed his limited forces carefully. General Erich Straube’s 86th Corps defended Wesel. On Straube’s right was the 2nd Parachute Corps consisting of the 6th, 7th, and 8th Parachute Divisions, some 10,000 to 12,000 fighting men, who prided themselves on the elitism of being paratroopers, even if none were jump trained. The area south of Wesel was guarded by Schlemm’s weakest corps, the 63rd, under General Erich Abraham. Schlemm’s reserve was the 47th Panzer Corps, under Lt. Gen. Freiherr Heinrich von Leuttwitz, with the 116th Panzer Division and 15th Panzergrenadier Division in reserve. The two divisions had outstanding records but only 35 tanks between them.

Behind that, Schlemm had two more reserve formations—one was Volkssturm, the People’s Militia, made up of men over the age of 60 and boys under the age of 16. Trained hurriedly on Panzerfaust antitank weapons, Schlemm had 3,500 of these questionable troops at hand.

The second formation was even more questionable. Joseph Goebbels’s propaganda machine and Henrich Himmler’s Gestapo had created a resistance movement in the style of the French Underground, if not in their numbers. So far their most notable accomplishment had been to kill the pro-Allied mayor of Aachen, Franz Oppenhoff. They were tasked with sabotage missions, which included stringing cable across German roads to decapitate drivers of Allied jeeps advancing as they often did with the windshields down. In theory they were a considerable threat to the Allied advance, but as matters developed they would fizzle.

“My Orders are Categorical. Hang on!”

The overall picture for the Germans was bleak. They were short of everything. The Allied air forces dominated the skies. Morale was poor. To bolster it, the Germans tried a variety of measures—handing out medals galore, giving out autographed pictures of Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, and warnings that failure to resist would lead to a Soviet victory, which would follow with all of Germany being hauled off to Siberia as slave labor.

If that did not work, Hitler and his minions always had the favorite tool of dictators—the death penalty. Capital punishment was prescribed for a variety of offenses: failing to blow a bridge on time, being related to a deserter, withdrawing without orders, or failing to fight to the end. On February 12, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel signed an order warning that any officer who “aids a subordinate to leave the combat zone unlawfully, by carelessly issuing him a pass or other leave papers, citing a simulated reason, is to be considered a saboteur and will suffer death.”

Blaskowitz doled out death to stragglers: “As from midday 10 March, all soldiers in all branches of the Wehrmacht who may be encountered away from their units on roads or in villages, in supply columns or among groups of civilian refugees, or in dressing-stations when not wounded, and who announce that they are stragglers looking for their units, will be summarily tried and shot.”

Himmler topped them all on April 12 with a decree that read, “Towns, which are usually important communications centers, must be defended at any price. The battle commanders appointed for each town are personally held responsible for compliance with this order. Neglect of this duty on the part of the battle commander, or the attempt on the part of any civil servant to induce such neglect, is punishable by death.”

Kesselring put the situation simply: “My orders are categorical. Hang on!”

Still, German hopes were high. Schlemm told his bosses that if he was given eight or 10 days to reequip, prepare positions, bring up supplies, and rest,” he could stave off the attack.

Planning to Cross a “Large Slow River”

Montgomery gave him those 10 days—he even made it 12—as he continued his preparations. He needed the time, too. After setbacks against determined German defenses in Holland in September, the Ardennes in December, and the Reichswald in February, Monty was leaving nothing to chance. His plan called for hurling two British (15th Scottish and 51st Highland) and two American (30th and 79th) Divisions against the Germans. They would be reinforced by Canada’s 9th (Highland) Infantry Brigade, under the 51st Division, and the 1st Commando Brigade, veterans of Dieppe and Normandy.

The focal point of the assault was the rail and road center at Wesel. Simpson’s 9th Army would cross an 11-mile sector of the Rhine south of Wesel, code-named Flashpoint, in the early hours of March 24.

At that point, the Rhine was “a large slow river, slow of current, with ideal launching and landing sites, in which a mass of assault craft could be employed,” said 9th Army’s planning report.

With the Lippe River as the Army boundary, from Wesel north to Rees would be the 2nd Army’s attack area. Operation Turnscrew would be on the left at Rees and Operation Torchlight on the right at Xanten.

Turnscrew would go in first, at 9 pm on the 23rd. It called for the ebullient Lt. Gen. Brian Horrocks’s 30th Corps to storm the Rhine with Maj. Gen. T.M. Rennie’s 51st Highland Division and the 9th Canadian Brigade. As soon as these two forces were over the river, they would be reinforced by the 43rd Wessex Division, the 3rd Division, the Guards Armored Division, and two armored brigades.

One hour after the 51st crossed the Rhine, Operation Widgeon would commence, with 1st Commando Brigade making a silent river crossing behind Wesel and seizing the town after a massive air raid.

At 2 am on the 24th, the 15th Scottish Division would cross the Rhine at Xanten midway between Rees and Wesel. For Operation Torchlight, the 6-foot, 6-inch General C.M. “Tiny” Barber commanded the 15th Scottish, under Lt. Gen. Neil Ritchie’s 12th Corps. As soon as the Scots erected a Class 40 Bailey bridge across the Rhine, the 11th “Black Bull” Armored Division would rumble over for the breakout.

Finally, at dawn on the 24th, two airborne divisions, the British 6th and the American 17th, would parachute and glider assault onto the high ground near Wesel in Operation Varsity.

250,000 Tons of Supplies

The British and American troops continued to build up supplies. More than 250,000 tons were concentrated. The British alone stockpiled 60,000 tons of ammunition and 30,000 tons of engineer stores. The key to the invasion would be Buffaloes—a British version of the American amphibious personnel carrier called the Weasel, and Duplex Drive Sherman tanks, which had worked in the Normandy invasion. These tanks came with inflatable air tubes that made them amphibious for water crossings. The troops called them Donald Ducks.

Thirty Corps alone was assigned 8,000 engineers, supplied with 22,000 tons of assault bridging that included 25,000 wooden pontoons, 2,000 assault boats, 650 larger storm boats, and 120 river tugs. Eighty miles of balloon cable and 260 miles of steel wire were hauled to the Rhine’s banks.

The engineers had a tough job ahead of them—throwing bridges across the Rhine as soon as the attacking armies had consolidated their objectives on the far bank. The first Rhine assaulter, Julius Caesar, in 55 bc, had taken 10 days to construct a bridge across the river. The U.S. 9th Army was tasked with erecting an 1,152-foot treadway bridge nine hours after the attack was launched. Each division would have 9,000 engineers (sappers in British parlance). The engineers were responsible for bringing up not only all bridging equipment, but also all storm boats and rafts, tugs, landing craft, pontoons, anchors, and winches.

“The usual Hollywood words, such as colossal, stupendous, and unbelievable, would have been of little use in describing the situation as seen here,” said Royal Canadian Engineers Company Quarter Master Sergeant Samuel Alexander Flatt. “Nothing had been left to chance and a timetable had been worked out that reminded us of the detailed planning for the D-Day assault.”

Operation Plunder’s Massive Air Support

The air support was also gigantic. Starting in early February, the Royal Air Force and the U.S. Army Air Forces began to isolate the Ruhr by blasting 18 bridges on the most important routes leading to the area from central Germany. No targets were spared. The famous RAF No. 617 “Dam Busters” Squadron hit the Bielefeld rail viaduct with the new “Grand Slam” 22,000-pound “earthquake” bombs, whose heavy force and vibrations brought the massive rail bridge crashing down. By the time Plunder was ready to go, the Allies had dumped 31,635 tons of explosives in the area, and only three bridges remained standing.

Next the airmen hammered crossroads and communications centers to prevent German troop movements. While these attacks took place, fighters roared on armed reconnaissance missions to locate and destroy Luftwaffe fighter bases, particularly those used by the new German jet fighters. Fighter bombers pounded known German antiaircraft positions to suppress them.

The bombing had a major impact on March 22. One raid on Schlemm’s tactical HQ severely wounded the general and forced him out of the battle just before its start. Schlemm was replaced by General Gunther Blumentritt, a man who had seen and coped with numerous retreats as chief of staff to Field Marshal von Rundstedt.

“Two if by Sea”

The day before the attack, the British assembled 3,411 artillery pieces and the Americans 2,070 at the Rhine banks. The code message to launch the offensive harkened back to an earlier but less successful British offensive: “Two if by sea.”

While the gunners shoved their pieces into position, the invading troops got their final briefings and pep talks from their bosses. Field Marshal Montgomery told his men very simply, “21 Army Group will now cross the Rhine. The enemy possibly thinks he is safe behind this great river obstacle. We all agree that it is a great obstacle; but we will show the enemy that he is far from safe behind it. This great Allied fighting machine, composed of integrated land and air forces, will deal with the problem in no uncertain manner. And having crossed the Rhine, we will crack about in the plains of Northern Germany, chasing the enemy from pillar to post. The swifter and the more energetic our action, the sooner the war will be over, and that is what we all desire; to get on with the job and finish off the German war as soon as possible. Over the Rhine, then, let us go. And good hunting to you on the other side.”

With all the rehearsals completed, there was nothing more to do but wait for the order to attack. The 5th Black Watch held a night rehearsal and their Buffaloes got lost in the fog, landing at the wrong place. The 105th U.S. Engineers worried about keeping the Evinrude engines on their storm boats warm—they wrapped them in blankets obtained from their medical staff.

As in all military operations, there were still problems. The 44th Royal Tank Regiment was ordered to use DD tanks. Most of the tankers had never even seen one before, and they underwent 10 days of intensive training. Brigadier Derek Mills-Roberts was convinced the storm boats would be useless and took the 2nd Army commander, General Miles Dempsey, out on one for a trial run. Sure enough, the Army commander wound up adrift in the middle of a stream.

Security was tight. The 9th Army men removed shoulder patches, and unit identifications on vehicles were painted over. Patrolling was intensified to keep enemy saboteurs away from ammunition and bridging dumps. So secret was the troop buildup that the men of the 52nd Lowland Division, holding the Rhine riverbank, had no idea of the big offensive being heated up behind them.

A “Continuous Roar”: 13,896 Rounds of Artillery

Finally, on March 22, the generals began giving orders. The top brass came to watch. Prime Minister Winston Churchill joined Monty at the latter’s tactical headquarters. Churchill wanted to go up to the battlefield in a tank, but Montgomery was able to talk him out of it. Eisenhower strolled through the nervous men of the 29th Infantry Division, a 9th Army follow-up division, dispensing bonhomie.

The artillery bombardment began at 5 pm, under a precise schedule. Canadian Highland Light Infantry Private Glen Tomlin, aged 21, from Clinton, Ontario, described “an awful noise, the ground just shook, everything shook…. The guns started off and then you heard the shells come over, and they whistle different sounds for different shells.” As the guns increased their tempo, the sound became a “continuous roar.”

Canadian artillery units joined in the barrage, including their 17-pounder antitank guns, and the Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa Machine Gun Regiment, with their powerful Vickers machine guns, chattered with their two-mile range. British and Canadian gunners hammered predesignated ground targets, which included German bunkers dug in on the riverbank, with a massive volume of fire. The 4th Canadian Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment alone fired 13,896 rounds.

The Royal Marine Commandos Cross the Rhine

The first troops to attack would be some of Britain’s toughest, the 1,600 Army and Royal Marine Commandos of 1st Commando Brigade.

At one minute before 10 pm on March 23, the first Buffaloes, jammed with 46th Royal Marine Commando, rumbled over the dike in front of the Rhine River and into the waters. Operation Widgeon was going in under a three-quarter moon and heavy smoke screen.

As the Buffaloes clattered across the Rhine, 5,500 heavy guns opened fire in a single, solid roar. Shells and explosions lit up the night. The Buffaloes coursed across the Rhine, battling heavy current, submerged with only a foot of freeboard. It took the amphibious vehicles only three and a half minutes to cross the river, and then they nosed up on the enemy shore. German mortars fired at the advancing Buffaloes. A phosphorous round went off in one Buffalo, and flames shot 15 feet into the air. Nine men were killed. The well-trained Commandos swept past the carnage and stormed onto the beach, overrunning the German trenches and gun emplacements, churning through mud.

Brigadier Mills-Roberts had chosen this muddy site as a landing beach because of its seeming unsuitability. He knew his Commandos could overcome it. However, they could not make a frontal assault on Wesel and its defenses. His men were to slip in from the side and surprise the German defenders.

“Monocled Major Swims the Rhine”

As soon as 46th Royal Marine Commando was deposited on the beach, the Buffaloes headed back and another wave of invaders arrived, 6 Army Commando, with orders to exploit the new bridgehead. Six Commando crossed the Rhine in storm boats, which proved temperamental in action. Six Commando’s commander, Lt. Col. A.D. Lewis, recalled, “One boat was overladen. When the driver took off, the thing dove straight into the water. Many of the men had their rucksacks still on their backs (instead of loosening them as they were meant to once they got aboard), and some were drowned with the weight of them.

“My second-in-command happened to be in that boat. Fortunately, he had taken off his rucksack so he was rescued. He used to wear a monocle quite frequently, so the Daily Mirror came out with a headline: ‘Monocled Major Swims the Rhine.’”

“A Terrific Sight”

The 45th Royal Marine Commando was next, and Marine Tom Buckingham recalled the crossing: “On the evening of 23 March the barrage opened up and we set off in single file for the bank of the Rhine. Finding the way was easy because the Royal Artillery had a pair of Bofors guns firing two lines of red tracers to mark our route. We marched under the tracers and thousands of shells screamed over our heads and hit the enemy positions on the far bank. Before we crossed, the RAF had a part to play. Spot on 2045 hours, the artillery fire ceased and precisely on time the Pathfinders dropped flares over the town of Wesel, marking the target. More than 200 heavy bombers then plastered the place.”

Some 250 Avro Lancaster bombers from Bomber Command hammered Wesel that evening, turning the town to rubble with 1,100 tons of high explosive. The leading Commandos were just a half-mile behind the bomb line.

Buckingham recalled, “We must have had the best ever view of RAF heavies doing their stuff. The ground shook with exploding bombs, but we were surprised to see the Germans fighting back, sending up a barrage of antiaircraft fire. Then it was our turn. We embarked in Buffaloes, tracked vehicles which could traverse ground or water, and set off across the Rhine. There was little resistance, and although some German fire came our way and one craft received a direct hit from a mortar bomb, the landing was relatively unopposed.”

Royal Engineer Corporal Ramsey, with a bridging party on the west bank, said, “It was like fireworks. First a rain of golden sparks as the leading aircraft dropped the markers right over an enormous fire that already lit the town like a beacon. Then we heard the main force. It was a terrific sight. All colors of sparks flying everywhere, red, green, yellow and the fantastic concussion as the bombs went down. On our side of the river the ground shook and we could see waves of light shooting up into the smoke. It was like stoking a fire, the dull red glow burst into flames and it was like daylight.”

Many boats were hit by fire. Six Army Commando’s Regimental Sergeant Major Woodcock had three boats shot from under him before he could make a successful crossing.

5,000 Yards of Tape

Buckingham and the rest of the 1st Commando Brigade began moving in on Wesel. The British troops circled around and hit the town from the side with Commando infiltration tactics. The entire brigade advanced in single file following a trail of white tape laid by the lead Commando team. “It was a major operation, laying 5,000 yards of tape,” Lt. Col. Lewis said. “The tape was on reels. As we moved forward in single file, the man ahead carried the reels on his back. The soldier behind him would pull the tape out and stamp it in the ground.

“Seventy men were involved, some protecting the tape party and some being the tape party. One of the major problems was that, being in the lead, we had to cope with enemy opposition while at the same time staying on direction with map and compass and laying the tape.

“Luckily the opposition was fairly feeble. The Germans were stunned. All the fight had been taken out of them by the aerial attack. I can remember going down to a cellar to establish my HQ and finding 17 German soldiers down there, all lying in their bunks. There was no sort of control or command at that stage. The people fought as individuals.”

British Commandos took Germans prisoners and put them to work carrying equipment. “I’ve got a big bugger here, he’s doing grand,” one Commando said to his pal. The pal replied, “My little bugger isn’t doing too bad neither.”

Capturing Wesel

The Commandos arrived in Wesel around midnight and found the 13th century Hanseatic city in ruins but small battles exploding everywhere. “The streets were unrecognizable,” Mills-Roberts said. “Many of the buildings were mere mounds of rubble. Huge craters abounded and into these flowed water mains and sewers, accompanied by escapes of flaming gas.”

In the dark, Buckingham ran into his brigade commander, Mills-Roberts, who was standing on a pile of rubble illuminated by a burning building, urging his brigade to “get a bloody move on.”

The men of 6 Commando led the way into swirling smoke, sparks, and dirt. The defenders of the 180th Infantry Division reeled under the bombing but began to recover with their quick-firing MG42 machine guns. But the British were too much for the Germans.

By dawn, the Commandos had taken 400 POWs, and No. 45 Royal Marine Commando was dug in at a large factory full of hundreds of thousands of lavatory pans. A brigade signals group “swinging from girder to girder several hundred feet above the Rhine, under spasmodic fire,” managed to lay a telephone line across the river.

Lewis’s headquarters was across a small garden from the headquarters of the German garrison commander, Maj. Gen. Friedrich Deutsch, commander of the 16th Flak Division. Sgt. Maj. Woodcock led a charge into the underground shelter and found Deutsch himself shooting back. “Deutsch became very aggressive, quite dangerous,” Lewis recalled. “He had to be shot.”

Woodcock and his men found a map revealing all the German flak dispositions. This would be of inestimable assistance in knocking out the German flak defenses before the morning airborne drop.

By 1 am, the entire Commando brigade reached the center of Wesel, finding their maps useless—the town was a pile of rubble. Forty-five Royal Marine Commando joined the attack, and as Mills-Roberts stopped to talk to Lt. Col. Nicol Gray, their CO, a “dead” German SS soldier suddenly leaped to his feet clutching a Panzerfaust, which he fired at point-blank range. The blast knocked everyone off their feet as it exploded, wounding Gray, killing two of the HQ men. British Sten guns opened up, killing the SS man. After being assured he was dead, the British Commandos blasted every enemy corpse in sight, just in case.

Later in the morning, the Germans began counterattacking. “It got a bit rough towards 9:45 am,” Ward figured. “Our airborne were coming in at 10 am, so at 9:50 our artillery had to stop. We weren’t even allowed to fire a two-inch mortar. And that is when the Germans came back.”

For the next few hours the Commandos held off German counterattacks. Then, at 1:30 pm, the British artillery opened fire again. “This was the turning point in the whole battle and now I felt the brigade was secure in Wesel.”

The 51st Infantry Division Crosses the Rhine

Next, the 51st Infantry Division began its Rhine crossing in the Rees area. The 51st Division faced a river between 300 and 450 yards wide.

The 1st Gordons drew the job of capturing Rees, landing left of the town and swinging right in their advance to assault the enemy defenses. Major Martin Lindsey described “a tremendous rumble of guns behind us, their shells whistling overhead, and the nice, sharp, banging, bouncing sound of our 25-pounder shells landing on the far bank. But a mortar was still smacking down right in the loading area, and one dreaded the thought of a mortar bomb landing inside of a Buffalo with 28 Gordons inside.”

At 11:15 pm, the Gordons began to cross the river in their Buffaloes. The big vehicles trundled across the fields, past the dike, and dropped into the water. “The Buffaloes became waterborne, and then we had the feeling of floating down out of control, yet each Buffalo churned without difficulty out of Germany’s greatest barrier.”

Pipers led the Cameron Highlanders to their marshalling area, and General Rennie moved among his men, telling them they would make history in the crossing. Major Thomas Lansdale Rollo, commanding 7th Black Watch, made sure his signaler knew to immediately send out the message that the battalion was the first British battalion to cross the Rhine. When Rollo’s signaler sent the message, Horrocks shouted excitedly with relief.

The 51st’s leading attackers crossed in Buffaloes, but the follow-up battalions had to ride the despised storm boats. Only a dozen of the 30 available were serviceable. As each boat took only 10 men, the riflemen were delayed by as much as two hours in crossing. Fifty sappers were killed or drowned ferrying them across.

Despite this delay, the 51st moved quickly across the Rhine. The 7th Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders took 100 POWs. The 5th Black Watch and 1st Gordons headed for Rees, clearing a housing estate and taking 70 POWs. Rees was in a state of ruin and defended by two understrength battalions of paratroopers. The 1st Gordons attacked Rees, capturing a strongpoint in the cathedral at dawn and clearing the riverbank and town center later.

A Change in Command

Part of the 51st’s assault, the first Canadians over the Rhine were Acting Captain Donald Albert Pearce’s nine men of the Highland Light Infantry’s Bren carrier platoon, whose job was to guide the rifle companies to their predesignated assembly areas. At 3:45 am, the rest of the battalion followed in Buffaloes. The Canadians came under German shelling as their Buffaloes careened across the Rhine. Rumbling up onto a grassy mud flat two and a half miles west of Rees, the Canadians were dead on target, meeting Pearce’s party.

The Canadians stormed across the mud flat to secure the dike and ran smack into a group of Volkssturm armed with 1913 vintage rifles, all ready to surrender. By the time Lt. Col. Phil Strickland’s HQ party came ashore at 5:45 am, the riverbank was secure. But the village of Speldrop was not. The Canadians were told to stand by to support the 1st Black Watch, which was battling the tough men of the 8th Parachute Division in the village, which controlled the breakout route from the Rhine bank.

The 51st’s battle grew hotter, and Maj. Gen. Thomas Rennie, who commanded the division, went across the Rhine to check on his men and congratulate 7th Black Watch on being first over the river barrier. As he dismounted from his jeep, a mortar round landed. Rennie’s aide-de-camp asked, “Are you all right, sir?” but there was no reply. After 45 days of almost continual action—and five years of continual war—Rennie had been killed while leading his division to its final objective.

Major General Gordon MacMillan took over, but Rennie was beloved by his men, and shock waves pulsed through the 51st.

Hugging the Creeping Barrage: The Capture of Speldrop

So did German counterattacks. The Germans reinforced the defenders of Speldrop with the 115th Panzergrenadier Regiment, which left the Anglo-Canadian forces outnumbered. The 1st Black Watch was forced out of Speldrop by repeated counterattacks, losing 81 casualties including five officers. By late morning, the Highland Light Infantry was told to relieve the Black Watch and take over the fight. The Black Watch withdrew behind a smoke screen, leaving its wounded sheltering in place.

The Canadian CO, Phil Strickland, was highly regarded by his brigadier, John “Rocky” Rockingham, as being “terribly clever, full of courage and ability. I admired him most in the world.” He was a good tactician, meticulous and methodical.

Strickland’s plan to win Speldrop “relied strongly on artillery support to cover the troops into the town. All approaches were covered by the enemy with self-propelled guns, making it impossible to use tanks during the initial stages.” The ground was flat for the 1,200-yard approach and lacked cover. Strickland would overcome that with six field regiments of artillery, two medium regiments, and two 7.2-inch heavy batteries. Among them was Canada’s 14th Medium Regiment under Lt. Col. Gordon Browne, the first artillerymen to cross the Rhine.

The artillery provided smoke and creeping barrages ahead of the Canadian attack. By hugging the artillery barrage, Major Joseph Charles King’s B Company was able to cross the open terrain, which was swept by German machine guns and artillery. All three platoon leaders were hit—Lieutenants Bruce Frederick Zimmermann and Donald Arthur Isner were both killed and the third officer incapacitated. NCOs took over, and Major King ran from one farm building to another, directing the lead platoon while exposing himself to heavy machine-gun fire. Canadian troops advanced against farm buildings defended by German troops with machine guns and Panzerfaust antitank projectors.

Charge of the Bren Carriers

King realized his company might get torn up. He called for the Highland Light Infantry’s antitank platoon and its troop of three Wasp Mark II Bren carriers, which were rigged up as flamethrowers. These deadly little vehicles’ flamethrowers had a range of about 150 yards.

While the Bren carriers hustled up, B Company’s No. 12 Platoon punched in among the buildings and came under withering fire from 20mm antiaircraft guns. The platoon’s commander fell, and Lance Sergeant Cornelius Jerome Reidel “immediately took command of the platoon, ordered the men to fix bayonets, and taking a Bren gun, led the platoon into the orchard in the face of heavy small-arms fire. The platoon captured the orchard, and cleared the buildings beyond, killing 10 Germans and capturing 15 prisoners and three 7.5 centimeter infantry guns…. The success of the platoon action enabled the battalion to gain a foothold in the town,” Reidel’s Military Medal citation read.

Major John Alexander Ferguson led the column of Wasps and Bren carriers towing the four 6-pounder antitank guns into action. Ferguson earned a Military Cross in the action by riding ahead of his Bren carriers in a jeep checking for mines in the road.

The Canadians set up their antitank guns under heavy German fire. Sergeant Wilfred Francis Bunda calmly sited each gun and urged the gunners to dig in quickly. When several men were wounded, he ensured they were placed under cover and then oversaw their evacuation.

With the supporting weapons up, King led one B Company platoon forward and quickly cleared the fortified buildings. The Germans fought fanatically, but the Canadians showed ample determination. Lieutenant George Oxley MacDonald led his No. 8 Platoon in an attack across a 200-yard stretch of open ground to take one building, then charged forward under covering machine-gun fire toward the next building. There they laid down covering fire to enable another section to clear the remaining houses in their area. MacDonald’s “courageous and brilliant action” was recognized with a Military Cross.

When the Wasp flamethrowers finally were able to trundle into the village, the German defenses cracked. German troops surrendered rather than face the flamethrowers. Antitank guns blasted open enemy positions at close range and wrecked buildings. By dusk, the village was shattered and so were the German defenses. Around midnight, the Canadians caught up with the wounded Black Watch men, who had been huddling in cellars to avoid capture.

Savage fighting continued. “Houses had to be cleared at the point of the bayonet and single Germans made suicidal attempts to break up our attacks,” the Highland Light Infantry’s War Diary reported. “Wasp flamethrowers were used to good effect. It was necessary to push right through the town and drive the enemy out into the fields where they could be dealt with.” Some 35 dead Germans were counted around one farmstead.

Confidence in Planning

While the battle for Speldrop raged, Rockingham and the rest of the 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade crossed the Rhine. Rockingham set up his tactical HQ in the same building as the 154th Brigade to keep the Canadian relief seamless. At 2:05 pm, he briefed his two remaining battalion commanders on their duties. The Stormont, Dundas, and Glengarry Highlanders would relieve the 7th Black Watch, while the North Nova Scotia Highlanders would take over for the 7th Argylls in their attack on Bienan, which had so far proved futile. They would put in a night attack.

Meanwhile, the rest of Operation Plunder rolled on. While the 51st Highland Division launched its attack, so did the veteran 15th Scottish Division. The lead unit was Brigadier the Hon. H.C.H. Cummings-Bruce’s 144th Lowland Brigade, which sent two battalions across the Rhine, one in Buffaloes, the other in storm boats. The Germans were dug in behind a dike, ready to open fire on the invaders as soon as they scrambled from the river. Cummings-Bruce sited his guns around a bend in the river where they could “see” behind the dike and opened fire with a heavy barrage of Bofors 40mm and machine guns, thoroughly demoralizing as well as destroying the German defenders.

Major B.A. Fargus, the 8th Royal Scots’ adjutant, reported: “The principal memory of the Rhine crossings is the complete confidence we all had in the success of the operation. This was the result of the detailed and competent planning and the two rehearsals we had all taken part in on the Maas.”

The Royal Scots Advance

The 8th Royal Scots crossed in Buffaloes in three waves punctually at 2 am. The battalion suffered no casualties under light German fire.

On the other hand, the brigade’s other battalion, the 6th King’s Own Scottish Borderers, crossed the Rhine in storm boats. Lt. Col. Charles Richardson reported, “I recommended that the storm boat not be used again. A lot of my men had to paddle with their rifle butts or hands, landing hundreds of yards downstream.”

Even so, the 6th KOSBs formed up and headed for their objective, the village of Bislich, where they faced the German 1,062nd Grenadier Regiment. While the Scots and Germans battled, Royal Engineers began building pontoon bridges across the Rhine, which enabled the 44th Royal Tank Regiment to cross the Rhine and back up the attack.

By dusk, 44 Brigade had taken more than 1,000 POWs for a loss of fewer than 100 casualties.

The 15th Division’s other brigade, the 227th, under Brigadier R.M. Villiers, faced tougher opposition in the form of German paratroopers and a few female snipers. The 10th Highland Light Infantry loaded into its Buffaloes at 11 pm and drove to the river. Three hundred yards from the bank the Buffaloes fanned out and headed into the Rhine illuminated by a bright glow from the fighting at Wesel. The 2nd Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders also crossed in Buffaloes.

Brigadier Villiers wrote, “Everybody was keyed up for this great enterprise. There was the sound of firing on the far bank, but the river mist precluded us from seeing exactly what was happening. Everyone had been told to get their heads down below the waterline, except commanders, who could look out when they wanted. The mist was extremely thick; it was a combination of the river mist, the smoke screen which had gone on to the last moment, and the bursting of artillery shells. During the last five minutes before H-hour our artillery had plastered the edge of the far bank.”

The two Scottish battalions ran into heavy resistance, and it was not until 6:30 am that the Highland Light Infantry swept the enemy from their strongpoints at Overkamp.

The American Crossing

Now it was the Americans’ turn. At 1 am on the 24th, 40,000 American artillerymen and 2,070 guns opened up with a terrific bombardment of the Rhine’s far bank at Walsum opposite 16th Corps. Maj. Gen. John Anderson’s attack was codenamed Operation Flashpoint. The Americans hurled 65,261 rounds at the German defenses, backed by 1,500 heavy bombers.

Ninth Army commander Lt. Gen. Simpson and Eisenhower himself watched the attack from an observation post in a church tower. All three regiments of the 30th Infantry Division participated in the assault, the 119th on the left, attacking Buedrich, near the confluence of the Lippe and Rhine Rivers, while the 117th hit the center at the village of Wallach with the 120th Infantry two miles to the southeast near a big bend in the river just northeast of Rheinberg.

The regiments each used one battalion in the assault, and each battalion used 54 storm boats and 30 double assault boats. American covering fire was intense—German fire desultory. They knocked out two of the 119th Infantry’s storm boats, killing one man and wounding three.

Private Ralph Albert recalled the assault. “We got the boat over the dyke and seemed to have mastered the technique, but then someone tripped and we dropped the damn thing down the other side. It was a bit flustered for a few minutes but eventually we got the boat onto the water and piled in.”

Albert and his pals saw a panorama of red tracer, smoke, and small boats motoring across the river. “We all got as low as we could,” Albert said, “because there was a lot of enemy fire coming across, as well as water spraying over us which made it difficult to see. A boat alongside us was hit by a burst of gunfire, which killed the engineer steering it, and slammed into us, almost capsizing our own boat before it rocked away and turned over. I think it was hit by a cannon shell.”

In minutes the Americans came charging from their assault boats on the far side of the Rhine and charged the big dike. The Germans fought back at only one point, hammering G Company of the 120th with machine-gun fire, but the Americans silenced them without loss. “There was no real fight to it,” said Lieutenant Whitney O. Refvem, commander of the 117th Infantry’s Company B. “The artillery had done the job for us.

“We captured a German soldier at the dyke and used him as a guide through the minefields. We reached the town without encountering any mines, taking prisoners as we went.”

“There could be no question from the first that the 30th Division had staged a strikingly successful crossing of the sprawling Rhine,” wrote official historian Charles B. MacDonald. “Within two hours of the jump-off, the first line of settlements east of the river was in hand, all three regiments had at least two battalions across, and a platoon of DD tanks had arrived to help the center regiment. In the assault crossing total casualties among all three regiments were even less than for the one regiment that had made the Third Army’s surprise crossing 28 hours earlier at Oppenheim.”

The 300,000th Shell

The last crossing was made by the 79th Infantry, which sent two regiments over in the first wave, using only storm boats initially. The 79th’s assault went in at 3 am, and the major problem for the invaders was fog and smoke, not German defenses. Some boats lost their way in the smoke and mist and landed their troops on the western bank. Men in one boat charged forward in a skirmish line, only to meet other Americans coming down to the water to load.

But with German opposition slight, the Americans reassembled quickly and began heading across the Rhine and inland, collecting German POWs. Prisoners said they had never encountered anything like the artillery barrage, and it completely stunned them. The two divisions had crossed one of the greatest water obstacles in Europe at a cost of 31 casualties.

Sergeant William L. McBride of the 311th Field Artillery Battalion took time to scrawl “300,000” on a shell, marking the 300,000th shell the Americans had fired off in the space of one hour. During the artillery barrage, mortars fired 1,000 rounds on the far shore to detonate mines.

Paralysis of the German Defenders

As the sun rose, the Americans headed inland. The 79th Division’s 315th Infantry headed for the city of Dinslaken with its population of 25,000, against spotty resistance. The 79th did not even call upon air support, instead relying on a weapon borrowed from the enemy—captured Panzerfaust launchers. The 79th had captured several hundred of them and passed them out to the assault battalions. The Americans found them very handy at blasting open buildings and convincing even the most diehard occupants to surrender. More than 700 POWs were taken, and American casualties were few. The 313th Infantry lost one man killed and 11 wounded.

As the 24th rolled on, so did the 79th. By nightfall, the division held a bridgehead more than three miles wide and deep, which included Dinslaken. The 30th Division had a tougher time, striking into the center of the 180th Division. The Americans rolled tanks across the Rhine on Bailey rafts and tank destroyers on landing craft to hook up with the offensive, and the 30th was soon rolling again. As night fell on the first day, the 30th had taken 1,500 prisoners, twice those taken by the 79th.

Meanwhile, the British continued to advance and consolidate their gains, which were heavily covered by the press. During the first four days, 79 radio photos were sent from London to New York for coverage in the American papers. Ninth Army Press Camp had 39 accredited correspondents who filed 226 stories totaling 74,510 words, including broadcasts.

By the early hours of March 24, the British were moving inland. The Germans were overwhelmed. To make matters worse for the defenders, they would soon have trouble moving up reserves as Operation Varsity, the airborne component of the assault, would take place, delivering thousands of paratroopers behind the German lines. Many German troops had to stay in place to guard against further airborne assaults.

Otto Diels, with the 146th Panzer Artillery, recalled, “My battalion was at readiness from about midnight, but to our surprise no more orders came and we waited until the morning.”

With a massive British offensive in motion, the Germans could not decide where to counterattack.

While the Germans dithered, the British advanced. Mills-Roberts’s Commandos, facing German counterattacks, called down heavy artillery fire, which silenced the Germans.

‘First to the Bottom of the Rhine, 2 Baker’

At Rees, the 51st Highland Division’s 2nd Seaforths moved out to seize the main road. The Seaforths brushed aside German resistance, filled in an antitank ditch, then faced a counterattack. The Seaforths shoved a Bren gun in position and stitched up the Germans. The Seaforths called for a troop of tanks to clear out a factory, but there were none available. For the next few hours they held out while the Germans moved due east, calling down artillery fire on them.

At 4 am, the 44th Royal Tank Regiment rumbled across the Rhine in its DD tanks “looking like floating baths drifting downstream,” according to their CO, Lt. Col. G.C. Hopkinson. “One tank was hit as it left the shore and sank like a stone, all the crew abandoning ship and making shore safely. This crew later carried a swastika flag emblazoned ‘First to the bottom of the Rhine, 2 Baker.’ The last tank of A Squadron was hit as it was going down the runway to the water, but it managed to reverse out and retired for patching. Regimental HQ nipped in while the enemy was adjusting for range and, except for a few splashes in midstream, had no trouble.”

The 44th RTR emerged from the Rhine to support the 1st Gordons, which needed the help under heavy shelling as it struggled to take a housing estate on the outskirts of Rees, held by the tough 19th Parachute Regiment. The tanks rumbled into action with their 75mm shells blasting through German defenses.

German Counterattacks

At 9 am, the Germans counterattacked in bright sunshine near Wesel with waves of panzergrenadiers backed by Mark IV tanks and assault guns storming the Commando positions. The Commandos opened fire with automatic weapons, gunning down the attacking infantry, leaving the tanks unsupported. The Germans, unsure about the British defenses, did not know that the only antitank weapons the British had were captured Panzerfausts and PIAT projectors. The Germans decided to attack anyway, and Easy Troop let the Germans come to near point-blank range. Then the lead tank stopped and retreated. All the Commandos let out sighs of relief.

Another battle took place in a factory that made lavatories. German troops tried to cross open ground but Commando fire was deadly accurate. Number 3 Army Commando reported, “One patrol came down the railway lines and we waited until we could literally see the whites of their eyes before killing them with Bren and Tommy guns. Later a section of Germans came across the fields … we just picked them off like sitting birds. They had no idea where the fire was coming from and simply lay on the ground ready to be shot.”

“Here Come the Airborne!”

Now all the advancing Allied soldiers looked to the sky to watch the massive airborne operation take place. Trooper Bob Nunn recalled the rumble of guns stopping. “Then we heard it, and the Germans too; we could see them staring up at the sky. The air filled with the drone of thousands of aircraft. We couldn’t see them at first but then they were there, huge lines of Dakotas. It was a marvelous sight and everyone stopped to cheer them. Somebody started yelling ‘Here come the Airborne!’”

As the day turned to afternoon, the American and British engineers took over, hurling pontoon bridges across the Rhine, enabling tanks, heavy vehicles, and reserve forces to cross the river with ease. British bridges drew names like Blackfriars and Whitechapel. The Americans had a 1,152-foot treadway bridge across the Rhine by late afternoon. Three hours later, a raft with a tank aboard smashed into it. Undeterred, American engineers had the bridge rebuilt by 2 am on March 25.

Late that evening, the last major attack of the day went forward, the Canadian Stormont, Dundas, and Glengarry Highlanders relieving the 7th Black Watch in the dark, on the extreme left flank. Lieutenant J.C. Kirby wrote, “It is a bright moonlit night, and a very noisy one. Our artillery is putting up a terrific barrage and Jerry is tossing over the odd shell, some of which land uncomfortably close to this HQ. We lend a cynical ear to the commentators who babble about the light resistance offered by the Jerries to our landing across the Rhine, and who talk about our great advances. From where we sit it looks rugged…. The SDG (the Stormont, Dundas, and Glengarry Highlanders) have the unique position of being on the left of the whole Allied push.”

That push would not come until 6:30 am the following day, and the Canadians would attack up sodden roads, backed by artillery and Wasp flamethrowers.

By then, the Allied victory was fairly complete. As night fell, the 51st Highland Division and the 9th Canadian Brigade fought hard against German paratroopers, but the rest of the German situation was precarious. The Anglo-American outpouring of artillery and airpower combined with overwhelming infantry and tank force was too much for the German defenses. With paratroopers now in their rear, the Germans could not hold.

Final Victory: Churchill Crosses the Rhine

By March 28, the bridgehead was 35 miles wide and extended to an average depth of 20 miles. All opposition had virtually collapsed. The three Allied armies were fanning out, the Canadians toward Holland, the British toward the German ports, the Americans to surround the Ruhr. British historian Hubert Essame wrote, “Judged purely as a military operation, it is impossible to fault Montgomery’s plan and its execution—the linking together of the land and air operations, the achievement of concentrated firepower both from the ground and the air, the foresight devoted to tactical and administrative planning and the exploitation to the full of the characteristics of the many components of the land and air forces. It was Montgomery’s final masterpiece, executed in a manner soon to be outmoded, but nonetheless, like a Constable, a work of art.”

Among the connoisseurs of the artwork that morning of March 24 was Winston Churchill himself, watching the massive assault at the 9th Army’s crossing point at Rheinberg. He saw it all—the artillery barrage, the airborne forces fly overhead, the American and British infantry go across the Rhine. Later in the day Churchill himself crossed the Rhine with Montgomery in a U.S. Navy craft, touring the battlefield, avoiding German artillery fire.

But before he went across the Rhine, Churchill delivered a simple and accurate analysis of the situation to Eisenhower. Watching the offensive go forward, Churchill repeated to Eisenhower, “My dear general, the German is whipped. We have got him. He is all through.”

David Lippman is a frequent contributor to WWII History. He also maintains a website dedicated to the daily events of World War II.

My home was Duisburg, 20 miles from Wesel. I experienced the carpet bombing, events difficult to describe. I left town in November, 1944, and I missed the shelling. I have high regards for the landing troops. Their courage an sacrifices ensured the freedom I now enjoy. Thank you America and England. Klaus O. Staerker

Glad you enjoyed the article and I am very sorry your town suffered so heavily.

My father, Gerard Quinn was killed on March 25, 45 as the 71st approached Germersheim. Looking for any details of what went on during that time as they tried to cross the Rheine.

The 71st Division association, like all US divisions, published its own history after the war.

The US Army’s Official History, “The Last Offensive,” will have outstanding information on that as well.

Redemption for Montgomery after several previous very questionable endeavors.

David Seeds north central Florida.

Monty went back to his successful method of the set-piece battle, which was his hallmark. Market-Garden failed because he did not make it a set-piece attack, and, worse, did not do hands-on management. He let it “run on rails.”

After the Market-Garden failure, he was more cautious in the freewheeling situation in the Bulge, where chaos was the order of the day.

He messed up Market-Garden because he did NOT do his usual set-piece planning, and did not manage the assault “hands-on,” which made it get out of control. If he had been at Nijmegen, he would have ordered a firmer drive north, and sacked some subordinates.

In the Bulge, Monty faced a wildly chaotic situation, and was reluctant after the Market-Garden failure to act too precipitately. The Germans were clearly showing incredible resilience in the face of continuing disaster.

Plunder was a great victory.

Interesting story, but the US Army forced a crossing of the Rhine at Remagen with far less buildup.

US Army found a relatively lightly defended bridge at Remagen, almost by accident. Hence, no build up. Was, of course, successfully exploited.