By Glenn Barnett

In June 1940, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini wrestled with a dilemma. German Chancellor Adolf Hitler was the very essence of a victorious warlord. Nazi forces were sweeping through northern France, having already overrun Norway, Holland, Belgium, and Luxembourg. These rapid conquests, added to the Germans’ previous victories in Austria, Czechoslovakia, and Poland, made the Third Reich the most powerful country in Europe, if not the world.

Mussolini had to decide whether to ally himself with the all-conquering Hitler and pick up some of the pieces of a crumbling Europe or remain in supportive neutrality and gain nothing.

Against the advice of his king and his Pope, Mussolini dispatched Italian troops into France to assist Hitler and cast his lot with the victor. To his surprise and embarrassment, Hitler would not let him occupy any significant French territory, only some disputed border areas. The Führer was cobbling together an alliance with the French government at Vichy, and the upstart Italian was inconveniently in the way. This border incident set the tone for the German-Italian alliance.

The dream of Mussolini and his Fascist party was to recreate the glory of ancient Rome. The immediate goal was to control the Mediterranean Sea, making it again the Mare Nostrum (Our Sea) of the Caesars. To that end, Italy pursued its own war aims independent of Germany.

As early as 1918, Mussolini had railed against foreign navies in the Mediterranean. This meant specifically Great Britain’s Royal Navy with its important bases at Alexandria, Gibraltar, and Malta. The French also had a powerful fleet and extensive Mediterranean bases. In the 1930s, Italy inaugurated a ship-building program that created a fleet of swift battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and motor torpedo boats that outclassed much of the aging English fleet.

The Royal Navy, with its proud tradition of ruling the waves for the previous four centuries, was hard-pressed by the German Kreigsmarine, whose U-Boats roamed at will in the Atlantic. Most of England’s naval strength was committed to convoy duty in the North Atlantic and the home waters to guard against a German invasion.

That left precious few second-rate ships to guard the important passage to India through the Mediterranean and the Suez Canal. Italian airplanes soon made Malta untenable as a naval base.

With the powerful French Navy neutralized by the armistice with Hitler and the British bombardment at Oran crippling the Vichy fleet, Mussolini was confident that he could defeat the scant British forces arrayed against him. The Mediterranean would become an Italian lake.

There were many factors that Mussolini did not consider when he went to war. Had he consulted with his naval officers, he would have learned that Italy had a finite amount of fuel oil for its thirsty ships. With both ends of the Mediterranean Sea controlled by the British, there would be no ready sources of oil available. The vast pools of oil in Italian-controlled Libya would not be tapped until after the war.

If the impending shortage came to his attention, Il Duce ignored it and began the systematic conquest of territory around the Mare Nostrum. But he bit off more than he could chew. From Libya, the Italian Army struck deep into Egypt to dislodge the stubborn English from Suez. In East Africa, Italian forces, now cut off from home, overran British Somaliland and tried to close the Red Sea to British shipping.

Meanwhile, other Italian forces invaded and occupied Albania. But when Greece became the next target of conquest, Italy got more than it bargained for. The Italian invasion of Greece stalled. Buttressed by British support, the Greeks threw back the assault and pursued the invader into Albania.

In Egypt, Britain gathered troops from throughout the empire to repulse Italian advances. On this front, Italian troops were pushed back into Libya. In desperation, Mussolini turned to his German ally for help. The result was the introduction of the small but tenacious German Africa Korps to North Africa. Units of the Luftwaffe also moved to bases in Sicily and North Africa.

In addition, Mussolini requested help from Hitler with the deteriorating situation in Greece. As the fortunes of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy became more intertwined, greater military cooperation was necessary. The Italian surface fleet was far more powerful than that of the Germans in the Mediterranean, and the Italian admirals felt they had little to gain from this coerced cooperation. But the German price of assistance in Greece was the proxy use of the Italian fleet.

Fairey Swordfish Torpedo Planes Sank or Damaged Several of Italy’s Capital Ships in a Daring Raid That Would Become the Inspiration for the Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor 13 Months Later.

The admirals of the Italian Navy, the Regia Marina, did manage to get Germany to commit stocks of fuel oil, but Germany had little of its own oil to spare and the shortage for the Italians would always be acute.

However, the British struck first in a bold move against their Mediterranean rivals. The bulk of the Italian fleet was anchored at the well-protected port of Taranto in the arch of the Italian boot. On the night of November 11, 1940, Fairey Swordfish torpedo planes from the aircraft career HMS Illustrious sank or damaged several of Italy’s capital ships in a daring raid. It was this innovative raid that became the inspiration for the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor 13 months later.

The crippled Italian fleet sought safer ports at Naples and in the Adriatic, where the warships remained at anchor for the next four months. But the Italians were still full of fight and desperately needed a victory. They would have preferred a fight of their own choosing, but the choice of a battle was made for them in Berlin.

Germany was willing to help Italy with the war with Greece, especially now that the British had become involved. Allied convoys of troops and supplies were moving freely between Alexandria and Athens, reinforcing the Greek counteroffensive. The Nazis wanted that supply line cut, and the Italian Navy was the only tool at hand. Germany was even willing to give the Italians some precious fuel oil for the impending naval offensive. The Italians grudgingly agreed to the proposal if the Germans could provide air support. The Germans, full of confidence, agreed. In February 1941, the senior naval staffs of each nation met for three days to plan joint operations.

Italy, like all belligerents in the war, was plagued by interservice rivalries. The Italian Air Force was vigilantly independent of the Navy and vice versa. If a naval commander needed tactical air support during a battle, he had to request it from the naval command headquarters. They passed on the request to the supreme command of all Italian forces, which in many cases meant Mussolini himself.

If he approved, the request went to the air force command and then, if convenient, to the individual aerodrome closest to the action. Divided German air authority on Italian soil only added time-consuming layers of bureaucracy in the lengthy command structure. By contrast, British commanders on the scene made all such tactical decisions and dispositions themselves without having to request permission from London.

Into the Italian cauldron of indecision was born Operation Gaudo, an effort to secure the seas around Greece. Hoping to catch a British convoy by surprise but unsure if a convoy was even at sea, a powerful Italian squadron weighed anchor on March 26, 1941. Steaming under radio silence, the Italians hoped to avenge Taranto and redeem the pride of their naval tradition. The Italian Admiral Angelo Iachino counted on the element of surprise but was already worried that no land-based German or Italian planes were overhead in support of his flotilla.

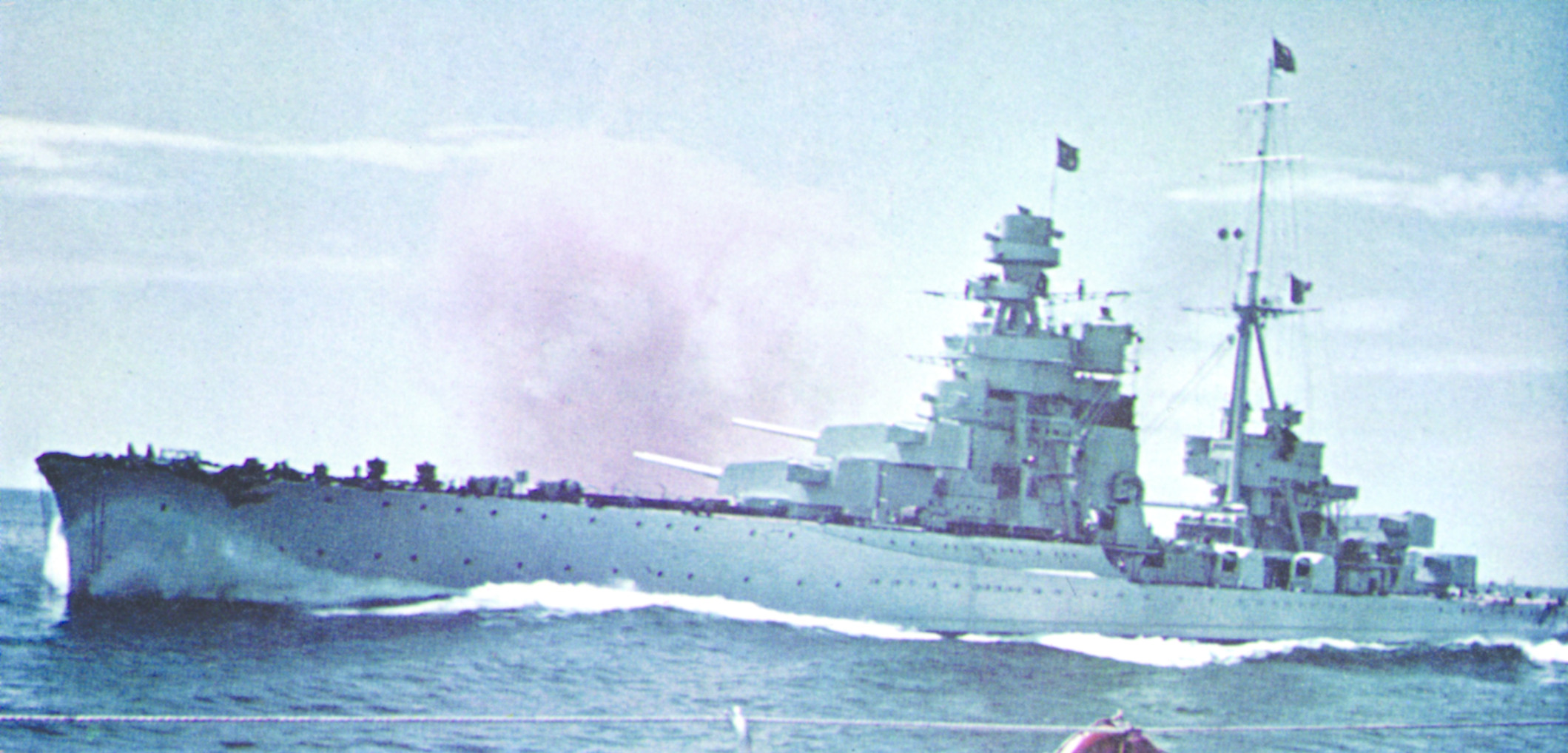

Aboard his flagship, the brand-new 45,000-ton battleship Vittorio Veneto, Iachino steamed out of Naples and moved boldly southward. Meanwhile, three squadrons of cruisers and a unit of destroyers departed from other Italian ports to rendezvous with him at sea. In all, his armada included the battleship, eight cruisers, and 13 destroyers.

On the 26th, an Italian spotter plane observed three British battleships, Warspite, Barham, and Valiant, and the aircraft carrier HMS Formidable resting quietly at anchor in Alexandria. So far Iachino was enjoying the element of surprise.

That same day, British scouting planes sighted one of the Italian cruiser squadrons, alerting the British to Italian naval activity but not unmasking their true intent. British codebreakers had also unlocked numerous German and Italian codes and provided intelligence on the Italian sortie. The British commander in Egypt, Admiral Andrew B. Cunningham, took heed of the warnings and alerted the 7th Cruiser Squadron, which consisted of four cruisers and two destroyers under Admiral Henry Pridham-Whippell. Cunningham ordered Pridham-Whippell to steam south of Crete to intercept what was then perceived as a single enemy cruiser squadron. A flight of 30 Bristol Blenheim bombers stationed in Greece was also put on alert.

Cunningham was convinced that there were significant Italian naval units at sea, though he could not yet determine their number, purpose, or destination. He ordered his three battleships and the carrier Formidable to build up steam and prepare to put to sea. Cunningham gave orders for all British units in the eastern Mediterranean to converge south of Crete at 1700 hours on March 28.

Meanwhile, the Italians continued to steam eastward toward the same waters south of Crete, still hoping to bag a fat British convoy. In a major failure of Italian reconnaissance, no flights were made over Alexandria on the 28th. This oversight kept Admiral Iachino from knowing that the main British fleet had departed the harbor and was steaming westward in the Mediterranean to join in the hunt.

But if the Italians had problems with their chain of command and intelligence, the British had to deal with ships that had been in almost constant service since the war began. Generally older, slower, and less well armed than their Italian counterparts, many British ships, especially the destroyers, had gone for long periods without routine maintenance. Some ships could not even leave port, while others had to turn back, and still others slowed down the newer, faster ships.

Outgunned by the Faster Italians, Pridham-Whippell Ordered a Retreat Toward the Safety of the Distant Battleships.

On the morning of the 28th, Iachino launched a short-range scout plane from the deck of the Vittorio Veneto at 0600 hours. The little plane would have to fly on to land, as the battleship was not equipped to retrieve and reuse her scouting planes as the British could.

The scout hit pay dirt. Only 50 miles ahead of the leading Italian cruiser squadron was the British squadron of Pridham-Whippell. The British cruisers were steaming in the area awaiting the expected convergence with the rest of the fleet.

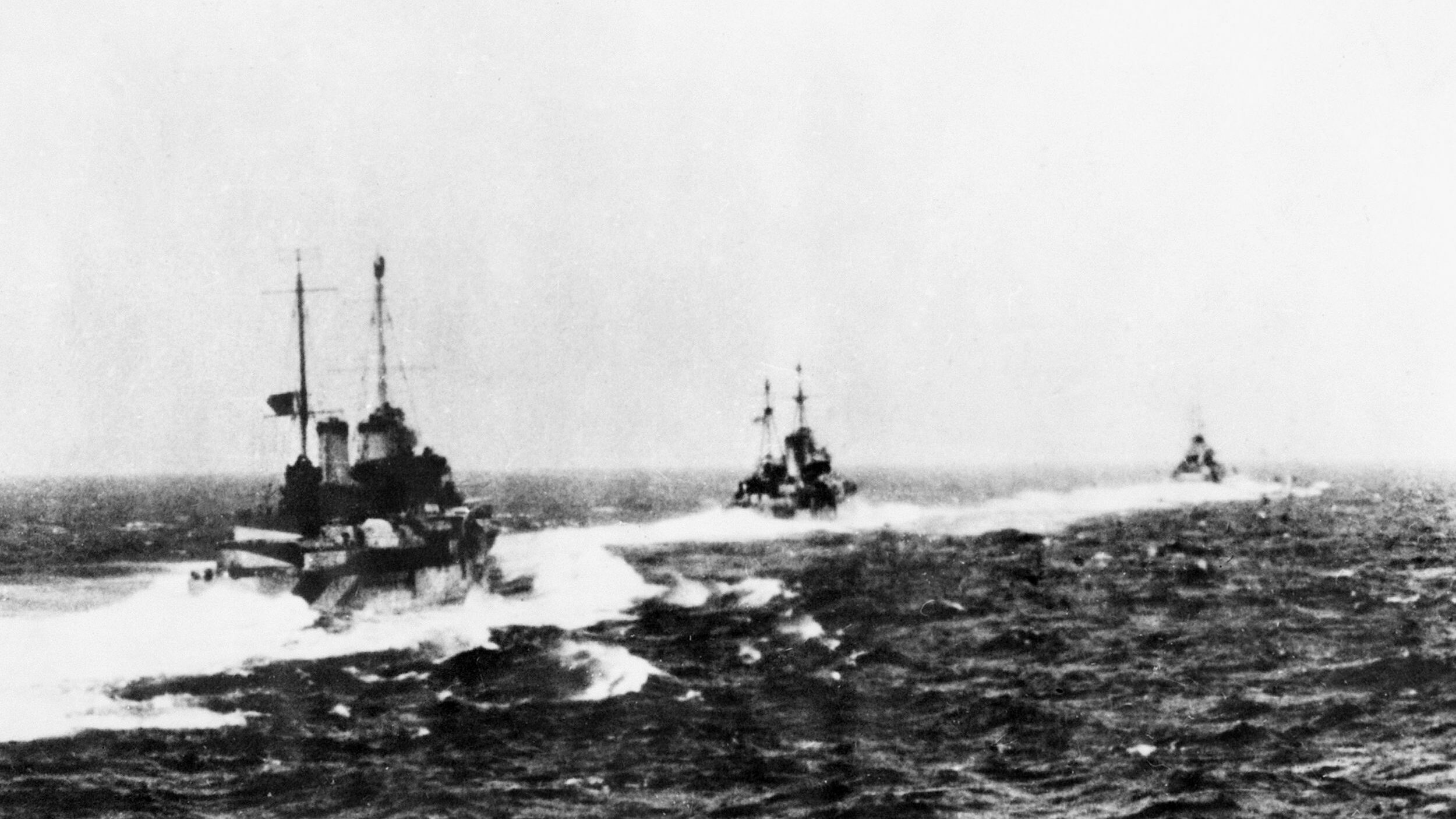

The combined Italian fleet increased speed from 23 to 30 knots to engage the outnumbered enemy. By 0745, lookouts on the cruiser HMS Orion sighted smoke from Italian cruisers. Knowing that he was outgunned by the faster Italians, Pridham-Whippell ordered a retreat toward the safety of the distant battleships. By 0812, the nearest Italian cruiser, Trieste, opened fire with her 8-inch guns on the slower moving cruiser HMS Gloucester, which was straggling at the end of the British line. Gloucester fired back with her 6-inch guns, but her shells fell short.

Aboard the Vittorio Veneto, Admiral Iachino distrusted the hasty British withdrawal. This timidity vexed him. He sensed a trap and ordered his cruisers to withdraw.

Meanwhile, the main British fleet under Cunningham had closed to within 70 miles. The British admiral was frustrated by the uneven speed of his fleet. The World War I-vintage Barham could barely keep up. Warspite, the flagship, struggled with mechanical problems and also lagged behind. The Australian cruiser HMAS Vendetta, another World War I veteran, was so slow she was ordered back to Alexandria.

When he learned of the Italian attack on Pridham-Whippell’s cruisers, Cunningham ordered the newest and fastest of the British battleships, the Valiant, to steam ahead with a brace of destroyers as escort. The Formidable was then ordered to launch her Fairey Albacore biplanes for a torpedo attack, but it would be nearly 1000 hours before they were all away.

Iachino was still unable to determine his enemy’s true strength. His own air reconnaissance was woefully inadequate, and the promised German and Italian air cover had not materialized. When he received news from an Italian aerodrome in Rhodes telling of two British battleships, an aircraft carrier, cruisers, and destroyers headed his way, he disregarded the message, thinking that the observers had spotted his own returning cruiser squadrons instead. He knew only that Pridham-Whippell had turned west once more, shadowing his cruisers. With the spotty information that he had, Iachino decided to attack the British cruisers once more.

By 1100 hours, the Orion once again sounded the alarm as smoke from Vittorio Veneto was spotted only 16 miles away. For the second time Pridham-Whippell ordered an about face while 15-inch shells from the Italian battleship rained down among his ships. Two cruisers were slightly damaged from near misses as the Italians closed in rapidly.

The attack was spoiled by the timely arrival of the first flight of Albacore torpedo planes, which caused the Vittorio Veneto to take evasive action, allowing the British cruisers to escape.

With no convoys spotted, reduced fuel reserves, and no air cover, Iachino decided to withdraw. The Albacore attack had alerted him to the presence of at least one British aircraft carrier. All the Italian ships were ordered to turn northwest for home. Yet, Iachino did not yet feel any urgency to get away and steamed at an economical speed to conserve precious fuel. The Italian admiral had been cautious, fearing the aggressiveness of the Royal Navy. Now, he ignored the thought that the British would seek every means to destroy him.

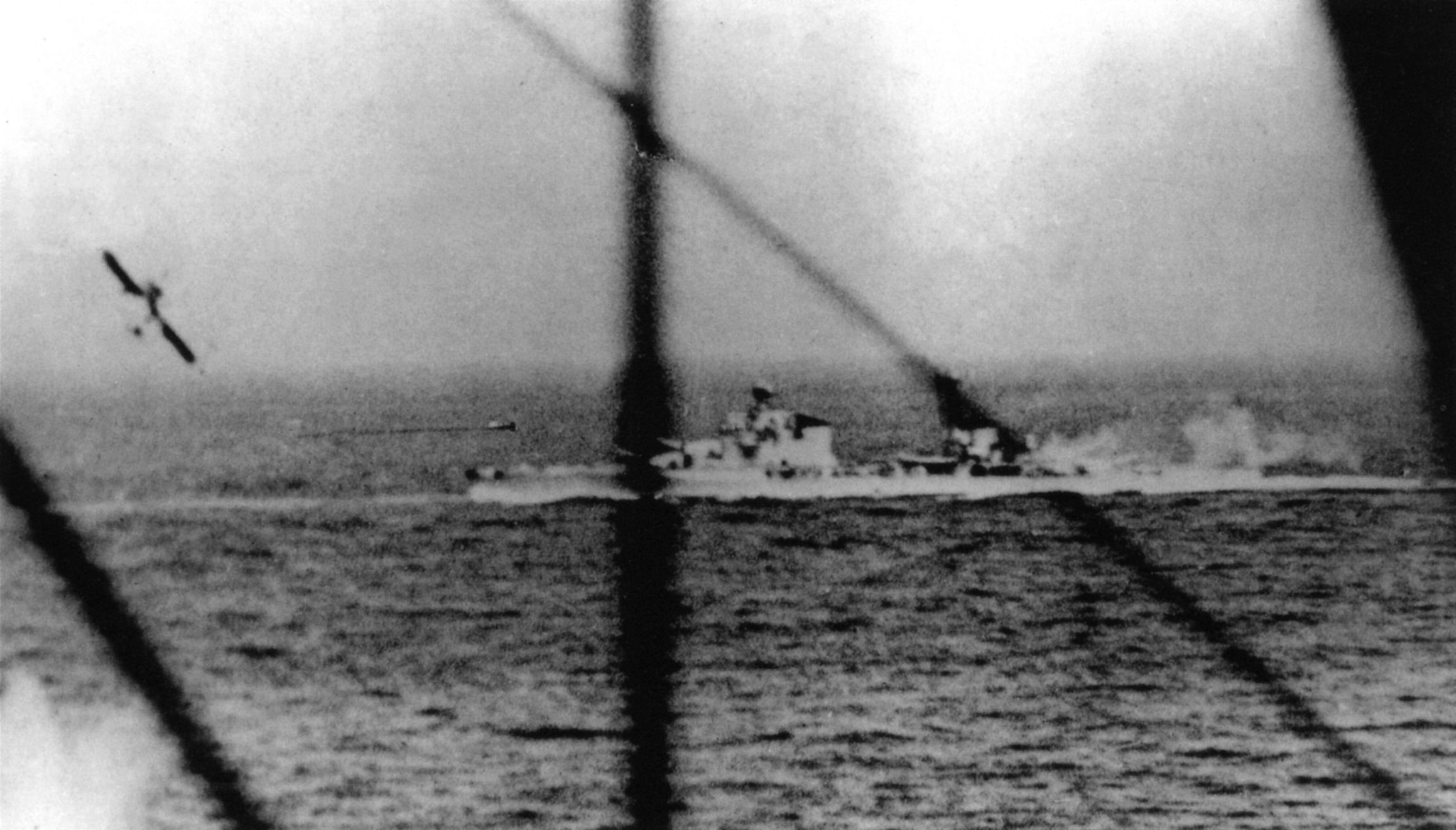

In fact, the British were just getting started. Formidable prepared to launch a second wave of planes, even while being attacked by Italian torpedo bombers. When the Italian attack ended, more planes were launched. By 1500 hours, three Albacores had found the Italian battleship and closed in. The Italians already had their hands full with a flight of Blenheim bombers that had joined in the chase.

While Italian gunners focused on the high- altitude Blenheims, the Albacores flew at low level out of the afternoon sun to completely surprise the Vittorio Veneto. At a range of 1,000 yards, one of the biplanes slammed a torpedo home before being shot out of the air. This single torpedo bomber would be the only British loss of the battle.

The Vittorio Veneto, hit in the stern below the waterline, took on water, lost power, and began settling by the stern. Her crew’s frantic efforts were enough to get her moving again but at a greatly reduced speed. Iachino now wanted nothing more than to reach the safety of Italy. Even though he still did not know it, the main British fleet under Cunningham was just 65 miles away and closing fast.

Fountains of Antiaircraft Fire Rose up from the Italian Ships in a Chaotic Display of Tracers, Searchlights, and Explosions.

At 1700 hours, Iachino was alerted that the two British cruiser groups were closing in on his stricken battleship. Still unseen, the three British battleships were right behind them.

By 1900 hours, the third and final aerial attack was shaping up. Six Albacore and four Fairey Swordfish torpedo planes from Formidable pressed toward the Italian fleet, which formed a protective cordon around the Vittorio Veneto. The main British fleet was closing to within 50 miles and preparing for night action. Racing at 30 knots, the leading destroyers spread out over a seven-mile area in an advanced screen looking for the enemy.

At 1930, the ancient-looking biplanes made their third attack of the day. Fountains of antiaircraft fire rose up from the Italian ships in a chaotic display of tracers, searchlights, and explosions. Only one hit was made by the attackers, but it proved critical to the outcome of the battle. The heavy cruiser Pola was struck by a torpedo and stopped dead in the water. Three of her wards were flooded, including her engine room. All electrical power was lost. The remaining Italian ships, ignorant of her plight, steamed westward into the growing darkness.

Cunningham had new worries of his own. If he pressed his night attack against the fleeing Italians, the morning might find him within range of Italian and German land-based planes. Subordinates warned him against pursuit, but he ignored their timid counsel and charged ahead. Valiant slowed to allow her sister battleships to catch up.

Night brought the advantage of radar to the British. They had secretly developed shipboard radar in the 1930s and were using it to good effect. In the early 1930s, the great Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi, father of the radio, had been actively working on shipboard shortwave radio-location, but with his death in 1937 his advances were not pursued. The Italians did not know that British ships were equipped with the device.

In the darkness, HMS Orion picked up the helpless Pola on her screen. At about the same time, Iachino finally learned of the plight of Pola. Still unaware of the onrushing British fleet, he impulsively dispatched the other cruisers of Pola’s squadron, Zara and Fiume, with their four destroyers, into the night to tow their stricken sister to safety.

The Italians were ordered to steam at 16 knots to conserve fuel. They were expected to complete the rescue mission and reach the safety of port before dawn exposed them to danger.

The leading British battleship in the nocturnal chase was now Warspite. Cunningham ordered a change of course for his battleships to intercept the invisible targets that radar had identified. The Italians were totally unaware of their presence. Neither navy had ever intentionally fought a battle at night, but the British, using their top secret radar, had been practicing during the 1930s for just such an occasion. The moment of truth had arrived.

Around 2230 hours, lookouts spotted the Italian cruisers in line-ahead formation. Admiral Cunningham ordered all three of his battleships on a parallel course. Their 15-inch guns were laid in at a range of only 3,800 yards.

At a signal, the destroyer HMS Greyhound illuminated the Fiume with her searchlights. All three battleships opened up with their 15-inch guns. Fiume, Zara, and the destroyer Alfieri were turned into burning wrecks within five minutes. The remaining Italian destroyers closed for an impotent torpedo attack before withdrawing into the night.

The British battleships made a 90-degree turn to retire and escape the counterattack. Cunningham ordered his destroyers to give chase. The action became highly confused in the night as the opposing destroyers sought each other in the darkness. In the firefight, the destroyer Carducci was also sunk. The remaining two Italian destroyers sped off to the northwest.

The Sailors were Soaking Wet and Shivering While Drinking Wine to Stay Warm, Which Would Give Rise to Later Rumors That the Italian Crew was Drunk.

Star shells were fired from the destroyer HMS Havock over the position where the crippled Zara was presumed to be. Instead, the listing Pola was illuminated. She was mistaken for the Vittorio Veneto. Havock fired twice into her bridge and reported finding the Italian battleship “undamaged and stopped.”

A prize crew was sent over to Pola to take command. Some 200 Pola crewmen were still aboard, having abandoned ship and then returned. They were soaking wet and shivering while drinking wine to stay warm. This would give rise to later rumors that the Italian crew was drunk. The British prize crew debated towing Pola back to Egypt, but soon abandoned the notion. They took off the surviving crewmen and sank the hapless Italian cruiser.

Pridham-Whippell’s cruisers, which were trailing the actual Italian battleship, reported that they had spotted Very lights over her position. Admiral Cunningham believed this sighting to be a new Italian squadron entering the fray and, to avoid confusion in the dark, ordered all of his ships not engaged with the enemy to turn northward simultaneously, allowing the remaining Italians to escape.

The searching British destroyers found the stricken Zara in the darkness and sank her. More Italian seamen were then in the water than the British destroyers could handle, though they picked up all they could. Some 900 Italians were plucked from the sea before 0800 the next morning when German dive-bombers arrived and chased the rescuers off. The British transmitted the location of the sailors still in the water to the Italian high command. Another 300 men were rescued by that evening. Curiously, Prime Minister Winston Churchill reprimanded Admiral Cunningham for this gallant action.

With the battle lost, the wounded Vittorio Veneto and her remaining escorts made it safely back to Italy. The British fleet prudently retired rather than face aerial assaults. The Battle of Cape Matapan was the last offensive operation of the Italian Navy in World War II. From then on only the destroyers and submarines and the occasional cruiser would play any part in staving off the growing power of the Allies.

Their one-sided victory did not let the British off the hook. The next two months witnessed considerable British naval losses in the Mediterranean from German bombers and U-boats. Many of the victorious ships and crews involved in the Battle of Cape Matapan were lost in the evacuation of Crete as Great Britain continued to stand alone against the Axis tide.

Glenn Barnett is a frequent contributor to WWII History. He is a freelance writer and an instructor of history at Cerritos College in Norwalk, California.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments