by Douglas Sterling

On the island of New Britain, at the north end of the Solomon chain, lay a major base that provided Japanese forces with the naval power, supplies, and reinforcements to control the sea lanes of the Southwest Pacific. It was also a nearly impregnable airbase and a haven for a large Japanese fleet of fighters and bombers.

This base, known as Rabaul, threatened any attempt by the Allies to return to the Philippines. In the summer of 1943, following the capture of Guadalcanal and the Allied naval victories in the southern Solomon Islands, a plan was hatched to capture this dangerous Japanese stronghold.

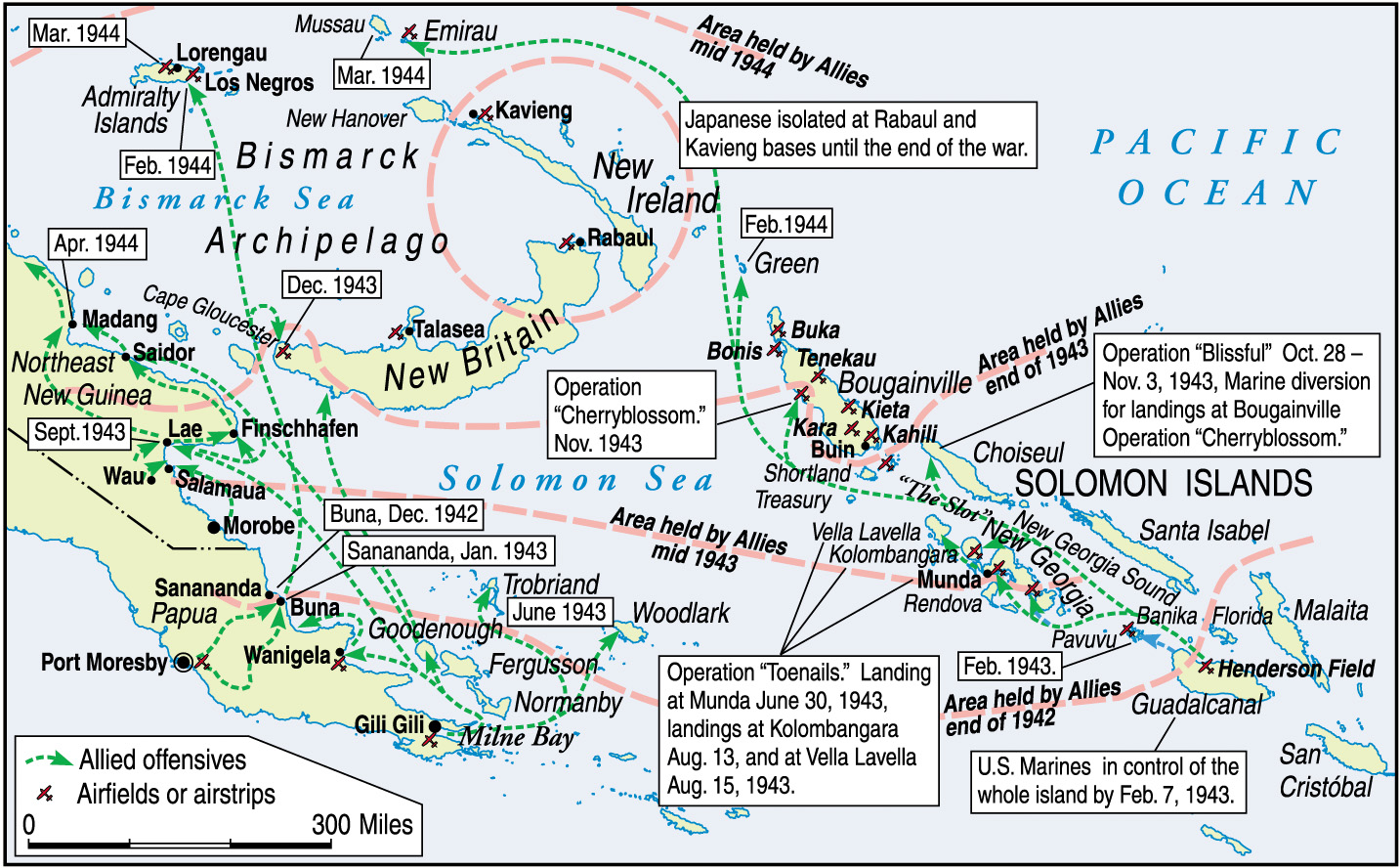

Designed by the Combined Chiefs of Staff and placed under the overall command of General Douglas MacArthur, the operation, designated Cartwheel, envisioned Allied forces advancing in two great wings. A western force would proceed up the coast of New Guinea, while another to the east climbed northwest along the Solomon chain and almost parallel to New Guinea. Together, these advancing wings were designed to trap Rabaul in a great pincer action.

Both marches were to be deliberate, capturing bases and islands from which to build airstrips and naval bases for resupply and air support. Cartwheel was a miniature version of the grand Allied offensive strategy. Calculated to culminate in the seizure of the Admiralty Islands, it was meant to be an integral part of the two larger prongs intended to at length threaten the Japanese occupation of the Philippines. It was the Philippines upon which MacArthur was ultimately focused, vowing to fulfill his promise, “I shall return.”

Cartwheel gained approval at the Casablanca Conference between British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and President Franklin D. Roosevelt and their military staffs. Both MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific and Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey’s Southern Pacific forces were to be under the overall direction of MacArthur. While Halsey oversaw the advance up the Solomons chain to Bouganville, MacArthur would lead the attack up the New Guinea coast to eventually land on New Britain and converge with Halsey’s group on Rabaul. With Rabaul isolated, the original intention was to capture the base.

Soon after, however, the Combined Chiefs determined that it would be more effective to bypass Rabaul, than to assault it. If it could be isolated and neutralized by air action from bases captured or built by the advancing Allied forces, then the strong and well-equipped garrison did not need to be taken and needless casualties would be avoided. MacArthur was originally against the decision, claiming that Rabaul was too strong to be left in the rear of his force and was in any case an excellent harbor ideal, in both a naval and air sense, to support his westward advance. MacArthur’s arguments failed to convince the Combined Chiefs, however, and no attempt was ever made to capture Rabaul.

MacArthur was to suffer a further disappointment when many of his and Halsey’s forces were earmarked instead to support Admiral Chester W. Nimitz’s advance through the Central Pacific. The Combined Chiefs’ decision effectively relegated MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific command to a supporting role. There developed a push and pull not only between the European Theater and the Pacific Theater for men, materil, warships, and transports, but between the plans for a Central Pacific drive and for the Southwest Pacific drive toward the Philippines and eventually Japan.

Nimitz preferred the Central Pacific because there was more room to maneuver, making his aircraft carrier task groups more effective. He felt that “the waters around New Guinea [were] too crowded for America’s growing fleet of aircraft carriers, that they would be exposed to attacks from land-based Japanese bombers.” Many believed his motive was to keep the carriers out of MacArthur’s hands. In the end, a compromise was reached. Both drives were authorized and actually became mutually supporting, each protecting the other’s flank and keeping the Japanese from concentrating sufficiently against either force. Halsey kept enough of his transports to move one reinforced division, and some of his warships. MacArthur kept the 1st Marine Division, while the 2nd Marine Division went to the Central Pacific Drive.

The two commanders employed different strategies. In the words of historian William Manchester, MacArthur’s intention “was to move land-based bombers forward in successive bounds to achieve local air superiority, while Nimitz’s was predicated on carrier air power protecting amphibious landings on key islands, which then became stepping-stones through the enemy’s defensive perimeters—but that was because they were dealing with different landscapes and seascapes.”

MacArthur’s key objective in taking land, whether on small islands or moving up the New Guinea coast, was to capture airfields or tracts where airfields could be constructed. “Victory depends on the advancement of the bomber line,” he is reported to have said. He counted on airpower as a sort of super-mobile artillery, considering bomber and short-range fighter attacks as forerunners of the land offensive. This was also true when the objective of Cartwheel was to the taking of Rabaul and not simply its neutralization. For, he knew that his forces would need to gain control of the air over New Britain if they were to have any success against Rabaul. Indeed, airpower would play a huge role in the Cartwheel advance, especially in the leapfrogging progress up New Guinea.

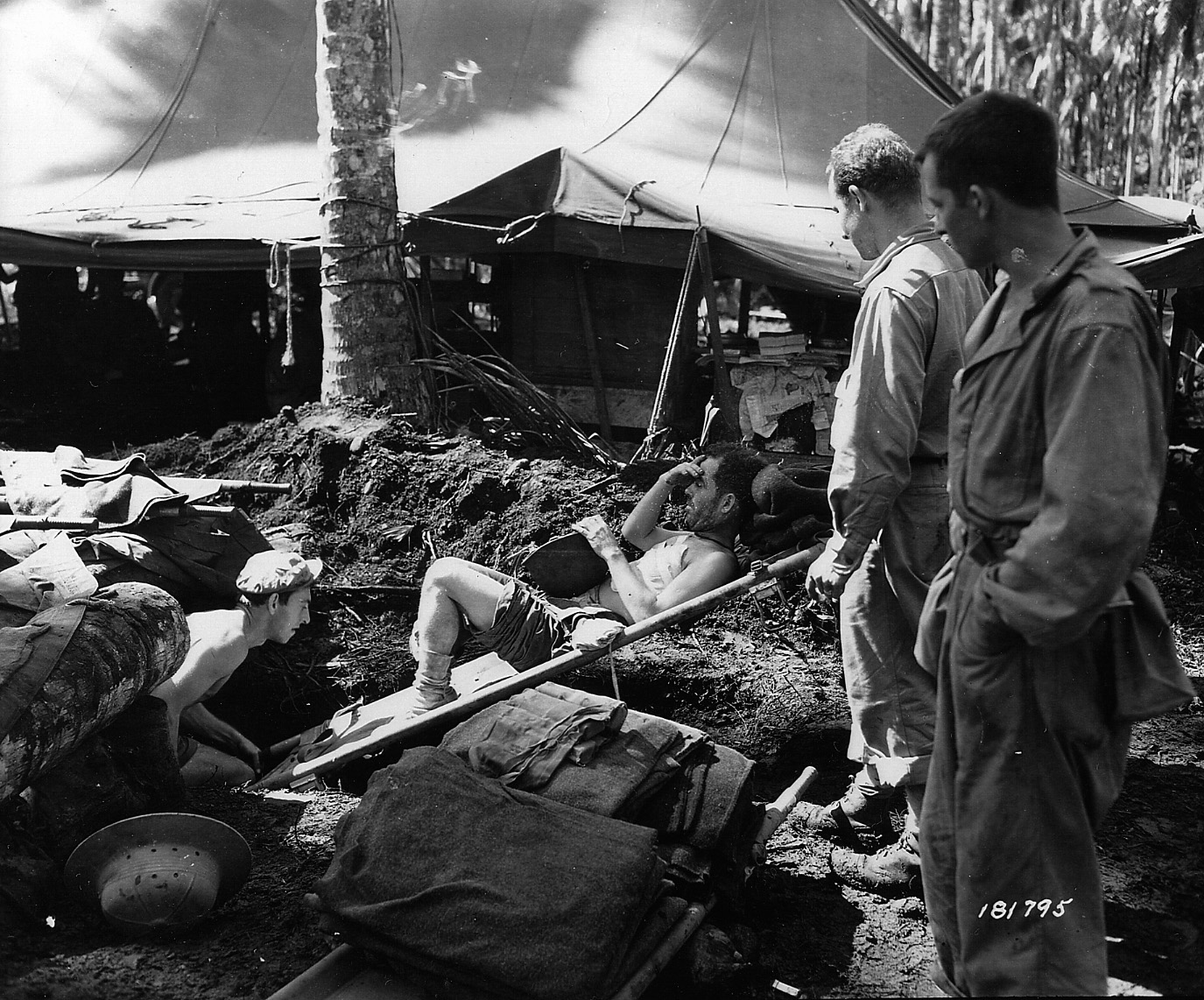

The initiation of Operation Cartwheel came after the capture of Buna and Gona on the Australians’drive from Port Moresby, and the lessons learned in this campaign were important in the management of Cartwheel. Buna’s capture was more difficult than had been expected due to faulty intelligence reports and ignorance—of the terrain, weather conditions, and the health of the Allied forces. The Fifth Air Force did not yet control the air, and the 32nd Infantry Division, earmarked to conduct the assault, had no experience in jungle warfare and little artillery support. The offensive against Buna, a two-pronged assault, quickly ground to a halt.

The battle essentially became a slugging match between ground forces. The Navy was loath to risk its ships in the uncharted waters off Buna. Air forces could not identify targets in the dense jungle and dropped bombs on their own troops, causing some casualties and seriously affecting morale, which was already depressed by the swampy insect-infested terrain and hot, humid air. A November 19 attack in the rain against Bun failed; an all-out attack along the entire front on November 22 was equally fruitless.

On the same day, the Australians, reinforced by two American battalions, launched a general attack against Gona and the Soputa-Sanananda road. No headway was made, but the Americans were working their way around the enemy position on the road, and by November 30 they had established a roadblock behind the Japanese, thereby cutting the supply line to Sanananda. The next three weeks were spent in maintaining this roadblock against desperate enemy attacks from all sides.

“It Was Not Rifles That Mattered; it was Artillery and Tanks.”

The infantry was worn out by the hot, humid conditions and by the onslaught of tropical disease. In addition, the officers of the 32nd were unaware of the extent of the Japanese defenses and manpower. In Brisbane, MacArthur, away from the fighting and ignorant of the conditions, instead concluded that the problem must be poor leadership. He sent the I Corps commander, General Robert Eichelberger, to investigate and to make changes if necessary. Eichelberger reluctantly did so, replacing the commander, Maj. Gen. Edwin Harding, but the problem was not in the leadership on the ground.

According to historian Geoffrey Perret, “MacArthur seemed to be thinking of the Western front, rather than the jungles and swamps of Papua. There was no elbow room for troops fighting their way into Buna. It was like crossing a bridge or advancing into a cave. It was not rifles that mattered; it was artillery and tanks.” What was needed were reinforcements, and Buna was not taken until they arrived, with a better logistical situation and long-awaited air support. When fresh firepower and fresh troops were supplied, the Japanese defensive system collapsed quickly.

The arrival of the veteran Australian 18th Infantry, along with seven light tanks allowed for an attack along the coast. With their tanks forming a wedge, the Australians charged between the Japanese defenses and the sea. A supporting attack from the west by two American and one Australian brigade cleared that section. Further attacks, even with weak firepower, finally drove the Japanese from the Buna region. But in Buna, the Allies came up against what would be typical of the Japanese: strong defenses based on interlocking entrenchments and bunkers with overlapping fields of fire.

The fall of Buna led to further attacks up the coast with the use of tanks and fresh reinforcements, tactics and capabilities the Japanese could not imitate. By the end of December, reinforcements had been flown in and blocked the Japanese, while the 127th Infantry Regiment moved north along the coast and an Australian brigade placed tanks before the southern Japanese roadblock. By January 9, attacks against those positions opened up routes to the west and up the coast. The 127th then was able to get behind the Japanese, return to the coast, and cut them off. By January 16, Papua New Guinea was in Allied hands; all that was left was to destroy the remaining strongpoints and defeat the Japanese holdouts.

MacArthur released a typically grandiose statement claiming that it was a well-designed and inexpensive victory. This was misleading at best. The campaign was not without its errors, missteps, and recklessness, and it was very costly. Over 4,000 Allied soldiers were killed, most of them Australian. However, the operation was a strategic success. Among other positive results, MacArthur had garnered airfields from which to strike at Rabaul with Air Force bombers and fighters of the air force, and from which he could cover the future assaults on Japanese strongpoints on New Guinea. MacArthur had also learned that, unless forced, he should abjure frontal attacks without adequate artillery or air preparation.

After the Papuan campaign, MacArthur’s supply and manpower situation greatly improved. By the start of the Cartwheel operation, he had four U.S. and six New Zealand and Australian divisions, with a number of specialized corps, including paratroop regiments. The Navy had sent a number of ships to his theater to augment his slight forces, adding some cruisers and destroyers as well as improved charts of the New Guinea waters.

Most important was the addition of landing craft. Also aiding MacArthur’s operations were new bombers and fighters arriving to serve with the Fifth Air Force. The added elements, which continued to grow, would be used to keep the pressure on Rabaul and other Japanese air and naval bases, as well as directly support MacArthur’s further operations on New Guinea.

One of the first uses of this augmented airpower capability was in the Battle of the Bismarck Sea, March 2-5, 1943. A large convoy of Japanese ships was seen at Rabaul, betraying the Japanese plan to reinforce one of their garrisons. It was believed the target was Lae, as the Japanese had previously landed a regiment there and launched a series of attacks.

On the last day of February, the convoy sailed from Rabaul. Spotted off Cape Gloucester at the western tip of New Britain, it was attacked by heavy bombers from the Fifth Air Force. The weak Japanese fighter support was intercepted, and the bombers, flying low and using skip-bombing techniques, devastated the convoy in three days of attacks. This battle was of tremendous importance to the success of Cartwheel as it so alarmed the Japanese high command that they never again sent large ships to reinforce their garrisons on New Guinea. As a result, those garrisons became more isolated and suffered great shortages of supplies.

In further attacks on New Guinea, the Allies executed a series of amphibious landings east of Lae on the coast south of the Huon Peninsula and in conjunction with an airlift of troops in the Japanese rear. After seizing the airstrip, the airlifted troops met up with the Australian 9th Division, which had landed on the beaches east of Lae. An amphibious landing to the west completed the three-pronged convergence on Lae. Air superiority was maintained not only by the capture of the airstrips, but by a well-timed assault on Japanese airfields which caught numerous enemy planes on the ground at Wewak. Combined with the Japanese commitment to the defense of Rabaul and the central Solomons, this spelled inadequate air protection for the Japanese in the region.

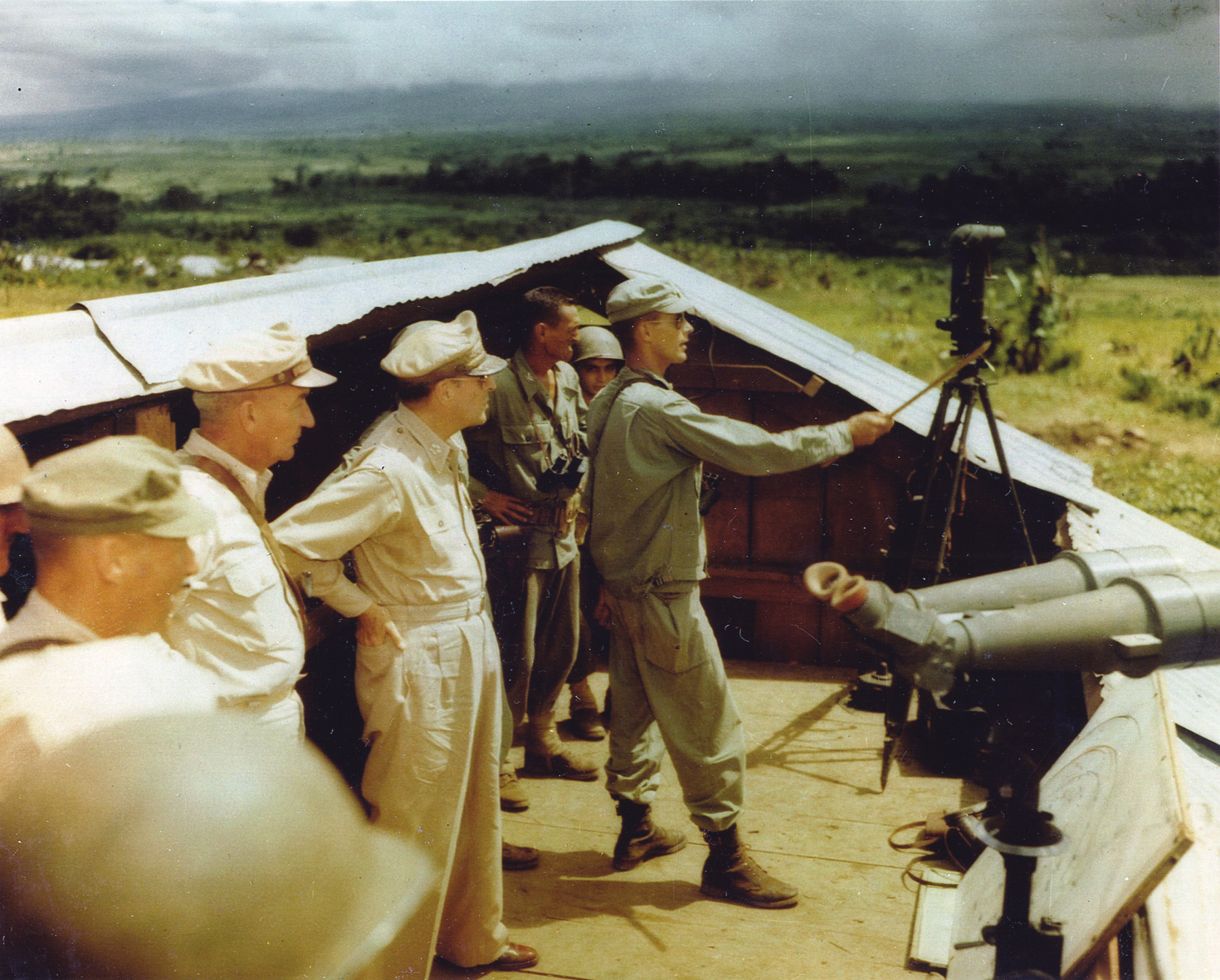

The Army relied on reconnaissance parties and coastwatchers, but Rear Admiral Daniel Barbey, commander of the 7th Amphibious Force which was responsible for the landing, preferred overlapping aerial photographs. He felt that interpretations of these photographic images were more reliable than the observations of local landowners who had not seen how the shore looked from the sea. Occasionally, he had some of his men make on-the-spot reconnaissance forays from rubber boats to obtain information.

Blamey Sharply Disagreed with MacArthur’s Downplaying of the Size of the Japanese Defensive Force

In the attack at Lae, Barbey was forced to work without information on the beach approaches. The landing craft were lightly loaded to facilitate transport and to return from the beaches quickly for use in resupply. The Navy obliged with four destroyers to sweep Huon Gulf and bombard the shore. Planes were sent to support the landing at daylight, and Barbey also had the destroyer USS Reid with a fighter director team stationed offshore.

The 9th Division was sent ashore near Lae on September 4, with the 7th landing by air to the north of the town the next day. Salamaua was captured on September 11 and Lae on the 16th.

Sir Thomas Blamey had taken command of the Australian forces on August 20, 1943. Before the operations against Lae, he decided, against Air Force and other objections, to bypass Salamaua and proceed directly to Lae. This would neutralize the Japanese at Salamaua, who would have no way of extricating themselves and thus would offer less of a threat. He also discussed with MacArthur an advance up the Markham Valley with airborne forces. In this way, the Allies could secure airfields to provide cover for operations against Cape Gloucester.

Winston Churchill described the importance of the Markham Valley which, “running northwest from Lae, had many potential air fields, and the 7th Australian Division, swift to exploit success, occupied its length in a series of airborne assaults. All the operations were well conceived and skilfully [sic] executed, and the co-operation of all three fighting Services was brought to a high pitch.” This is according to Churchill, though it may be accurate in a broader sense, to say that there were, nevertheless, disputes and interservice rivalries within the theater.

The next step was a seaborne attack on Finschafen along the New Guinea coast to the east of Lae. MacArthur and Blamey sharply disagreed on the expected enemy strength there, with MacArthur downplaying the size of the Japanese defensive force. The result of this dispute was dissension over the proper size of the assaulting force required to take Finschafen. Blamey wanted a landing with two brigades, while MacArthur thought one would be sufficient. In the end, Blamey ordered the second to be sent in, which caused a bitter dispute when Barbey hesitated to deploy it and, as it turned out, the Japanese were in greater strength than Australian intelligence had assumed.

D-day was September 22, 1943, and Barbey had only three days to plan, assemble ships, and load cargo and only six days to pick up troops. Barbey planned for his landing craft to hit the beach one hour before daylight and land troops along with 15 days of supplies. This was considered enough time in which to construct temporary landing areas for air support. The Japanese resistance was so stiff, however, that it took the full two weeks to get Finschafen declared secure. MacArthur accepted Blamey’s plan, despite objections from the U.S. Navy, which had wanted an advance along the New Guinea coast before the landing at Cape Gloucester. However, this was the last time Blamey exercised any influence as commander of the Allied land force.

MacArthur understood the significance of control of the seas, and he coupled that with the importance of control of the air in leading his advance to the Philippines. With control of the seas north of New Guinea, he would not need to advance through the 1,500 miles of jungle that lay between him and the staging areas necessary for a successful return to the Philippines. MacArthur, therefore, planned to use airpower to achieve the isolation of the battlefield.

A major component of this airpower in the New Guinea campaign was the implementation of tactical air doctrines developed by Major General Ennis Whitehead, deputy commander of the Fifth Air Force. According to historian Donald Goldstein, Whitehead’s tactics were simple. This included using his air reconnaissance and concentrating his airpower on individual targets rather than spreading his forces thinly over many targets. He would first gain air superiority in a given area, then isolate the enemy in this area on both land and sea by bombing and cutting him off from supplies and reinforcements, and finally blasting his ground position with heavy and medium bombers.

To facilitate this plan, Whitehead assigned the First Task Force of the Fifth Air Force to a hamlet called Dobodura on the other side of the Owen Stanley Range from Port Moresby. There, his forces constructed 70 airfields to facilitate attacks against Rabaul and other Japanese bases. As protection for the base at Dobodura, Whitehead had surprise landings made on a pair of islands off the New Guinea coast where airstrips were built.

The attacks on these islands, Kiriwina and Woodlark, fell under the codename Operation Chronicle and began on June 30, 1943. For Chronicle, Halsey loaned MacArthur ships, troops, and Seabees (Navy construction battalions) and provided Barbey with distant and close support. Barbey decided to approach the islands at night.

Observed by many high-ranking American officers, the mission “was fouled up from the beginning.” The landing craft, approaching the beach at 8 pm, had difficulty clearing a sandbar at the entrance to the channel and had problems maneuvering along the sloping beach. The Japanese offered no resistance. Yet, in spite of such drawbacks and a 50 percent seasick rate, Barbey moved 16,000 men and their supplies 185 miles through poorly charted waters without the loss of a single ship.

According to Goldstein and others, attacks from Dobodura on Rabaul were so effective that they made the Japanese sea and air bases at Rabaul untenable and ended their threat to the Allied advance along the New Guinea coast. It was this that made the Allied Supreme Command decide to bypass Rabaul rather than attempt to capture it.

Yet, before Rabaul could be effectively bypassed, it was necessary to neutralize the Japanese air base at Wewak, which was farther up the New Guinea coast and was a threat to any further Allied advance. Attacks there, however, were met with fierce antiaircraft and fighter defenses, resulting in heavy losses. Therefore, at NadzabWhitehead established the 309th Bomber Wing, which was composed of Australian and American airborne infantry that had been airdropped by troop carrier forces. From there that same force captured Marilinan, 40 miles southwest of Lae and Salamaua. This air base allowed Allied aircraft to refuel when returning to Dobodura and made possible fighter support for bombing raids over Wewak.

In a raid on August 17 1943, more than 200 Japanese aircraft were destroyed and Wewak was effectively neutralized. Like Rabaul, Wewak could be bypassed.

The campaign on Guadalcanal had exposed weaknesses in both Army and Navy jungle and island tactics and forced a reassessment that would lead to some of the innovations that came out of Cartwheel. Much of the criticism stemmed from a perceived absence of command unity and the differences between Army and Navy views of how to conduct operations.

Operational logistics were a significant problem in the Southwest Pacific due to numerous factors, including the scarcity of available shipping, a lack of unloading facilities and skilled dock labor, too few storage facilities, and an inadequate distribution system, to name only a few. The divided command and separate requisition systems maintained by the Army and Navy were also factors. Of course, the Allied situation was far better than that of the Japanese, and Japan’s would only grow worse with the increase in Allied air and naval power.

This concern about lack of shipping is evidence, however, of a significant advance in the Allies’ thinking. Planners were gaining an increasing appreciation, which grew exponentially after Guadalcanal, of the importance of the role of logistics and supply techniques in island warfare.

Halsey Had 250,000 Troops, 200 Bombers, 250 Fighters, to Work With to Accomplish Operation Cartwheel

The importance of logistics functions is well described by retired Marine officer and historian Joseph Alexander: “The impact of logistics on the vital element of acceleration, or momentum, in an opposed amphibious assault cannot be overstated. Assault troops have to dash ashore virtually naked, a storming party of riflemen and light machine gunners who cannot be slowed with logistical burdens. As developed in amphibious doctrine, tactical sustainability gets ashore by increments, first in follow-on scheduled waves, then in designated on-call waves, or ‘floating dumps,’ finally by general unloading once the beachhead has been secured to enable unrestricted, administrative flow of boats in and out.”

There developed a difference of opinion between the Navy and the landing forces over how long unloading should take. The Marines believed that offloading procedures should be the responsibility of the commander in charge on the beachhead. He would determine what supplies were needed and in what order.

The Navy considered the safety of the vulnerable transports to be paramount and insisted on control of offloading procedures to make sure the process was as quick and orderly as possible to free up the shipping for release from the dangerous shore. In the Solomons, the Navy generally got its wish, as the Japanese response to Allied landings was to effect strong air and surface counterattacks against the assaulting forces and their shipping.

The effectiveness of the Navy method was then gauged by how much around-the-clock unloading was required before the boats could get back to sea. Although the Finschafen landing on September 22, 1943, experienced some glitches and suffered from attacks by Japanese planes, the landing and unloading went at a faster rate than ever before. By sunrise on the 23rd, the landing ships were headed back to Lae to embark the follow-up forces.

Far to the southeast, Admiral William Halsey was conducting the right wing of the Cartwheel campaign. Among the forces under his general control, his Army commander had four divisions in addition to the 1st and 3rd Marine Divisions, which amounted to 250,000 troops, counting service personnel. The air forces available in the Solomons theater, known as AirSols, included 200 bombers and 250 fighters of all types from Marine Corps, Navy, and New Zealand air forces. Halsey did not have a large, permanent naval force, but was normally provided with what he needed for a specific mission by Nimitz. At the start of Cartwheel he had an amphibious force and two cruiser-destroyer forces that totaled eight cruisers and 16 destroyers. He also had at his service two aircraft carriers, the Saratoga and the Enterprise, and their attendant task forces.

After the fall of Guadalcanal, Halsey’s main objectives lay in MacArthur’s theater, and MacArthur was determined to utilize all the forces under his command to march toward Rabaul. According to Manchester, Halsey was proud to serve under MacArthur and he and his men had become “MacArthur’s right wing.” His capture of the Russell Islands, a part of the Solomon chain, was “intended to be a prelude to the admiral’s advance up the long ladder of the Solomons toward Rabaul, which would then be trapped between Halsey on the east and MacArthur on the west.”

The first assault in Halsey’s Solomon component of the Cartwheel plan was the capture of the airfields at Munda on New Georgia Island. Halsey developed a practically simple plan to land a division east of the airfield, break through the Japanese defenses, and seize the field. Simultaneously, another amphibious landing would be made on the north coast of the island to drive southwest and seize the harbor to prevent the Japanese from evacuating. The landing parties were to be supported by artillery from the nearby island of Rendova, which had been seized earlier.

The first part of the plan went well, though it was decided to land at Segei early. The shipping was not available for full-scale assaults, so relatively small forces went ashore at Segei and the three other landing sites where there were few Japanese. If the Japanese were able to occupy Segei before the arrival of the Americans, more troops might be required to take it, upsetting the complicated Cartwheel timetable.

With landings made, a harbor was secured for resupply and an airstrip begun at Segei point. Concern that Japanese forces were too strong at the original site prompted the decision to divert the main landings east of Munda airfield. When the Allied regiments proceeded toward Munda, stiff Japanese resistance stopped them. The Japanese had set up an extremely strong defense consisting of roadblocks east of Munda and fortified lines strung with automatic weapons. They were able to sever communication between the infantry on the Munda trail and the regiments along the beach. Supply was intermittent and morale sank. Frontal attacks along this sector made little headway. MacArthur had already learned that lesson in New Guinea.

The assault in the north sector of the island fared little better due to the toughness of the terrain and the stubbornness of the Japanese. Reinforcements were required there as well, but the naval support task groups had their own problems. Alhough outnumbering the Japanese naval forces in the area, the Allies had not yet overcome the superiority of the Japanese long lance torpedo. A Japanese task force delivering reinforcements clashed with an American task group, sinking a cruiser. Later, in spite of air attacks, another Japanese force made it through, although it did not reach the garrisons on New Georgia.

The Allies, however, continued to remain bogged down against Japanese resistance. Halsey sent Maj. Gen. Oscar Griswold to investigate, and he determined that the troops were “dispirited, exhausted, and suffering from low morale” he was critical of the dual command arrangement and felt the 43rd Division on the island would fold up under the pressure if they were not reinforced soon.

Consequently, the size of the invasion force was doubled with the commitment of additional regiments. This brought the size of the force up to what it should have been in the first place. There was a tendency among American commanders to initially underestimate Japanese resistance, leading to an inadequate force commitment. It was a hard-learned lesson.

A new offensive was ordered, which began on July 25th after the extensive employment of artillery and air and naval gunfire to knock out the Japanese fixed defenses. The Japanese fell back to rear defensive lines after suffering heavy losses. Some fell back even farther to a narrow perimeter around Munda Point, which conceded the airfield to the Americans. However, it took another three weeks before the Americans could capture the port, allowing the Japanese to evacuate most of their remaining troops to the islands of Kolombangara and Baanga.

Baanga was quickly captured by the Americans. Japanese troops on Kolombangara, while expecting to fight for possession of that island (if not attempt to retake New Georgia), were effectively isolated by the loss of a Japanese transport convoy in Vella Gulf off the coast. The Allied attack on the convoy sent some 1,500 Japanese soldiers to the bottom of the sea.

Halsey’s decision to take Vella LaVella, an ungarrisoned island to the north, effectively isolated the Japanese troops and, in a series of operations, they were evacuated to southern Bouganville. The Navy, like MacArthur’s forces on New Guinea, was getting the hang of leapfrogging past strong garrisons to cut them off and isolate them. Yet, the Japanese still had a large enough naval force to evacuate their men and save them for another fight, in spite of their now persistent state of defensive retreat.

At Bougainville, the next great test of Halsey’s climb up the Solomons ladder, the tactics were considerably altered, though the strategic concept remained the same. The objective was to seize and secure airbases from which fighters could support long-range bombers from Munda and Papua New Guinea in their attacks on Rabaul. The Japanese had built several airstrips and had a large garrison of almost 60,000 troops on Bougainville and the nearby islands. A reconnaissance assessment of the Japanese force determined that they were strongest at the southern tip of Bougainville, on the southern offshore Shortland islands, and at sites in the north and surrounding the airport on the eastern shore.

The original assault plan was scrapped due to the length of time devoted to Munda and the strength of the Japanese in the south. Therefore, Empress Augusta Bay on the western shore of the island was chosen as the landing site. Due to the dense jungle, the great distances, and the wide distribution of Japanese troops, the enemy would require a significant time to redeploy in support of any threatened points away from Japanese garrisons.

The Japanese Believed They Faced a Stronger Force Than had Actually Landed and Were Repulsed with Great Loss.

Halsey simply did not have enough troops to take on the 35,000 Japanese defending the airstrips. The Allied forces did not need to seize the entire island since control of a relatively small perimeter would be sufficient for the construction of an airstrip. The Japanese were counting on the Americans attacking them through the jungle terrain, where they expected to inflict heavy casualties. However, by March 1944, it was clear to the Japanese that the Americans were committed to a defensive strategy there and, if they wanted to prevail and to take out the vital airfield, the Japanese would themselves have to frontally attack.

Earlier landings were made in the Treasury Islands, both as support for Bougainville and as diversions, and another landing was carried out on the island of Choiseul, south of Bougainville, and used primarily as a feint. The Japanese would be expecting an attack there as the next logical step in the island hopping campaign, and therefore would be thoroughly fooled by the feint, even though the island itself was in relatively unimportant to the Americans. The bypassing technique, later so important, was still in a trial stage at this time, but the attack on Choiseul augured well for the strategy as the capture proved relatively easy and the Japanese were deceived.

The Parachute Battalion stormed ashore on Choiseul in an amphibious assault and captured the accessible enemy installations, while setting up a defensive position. The Japanese, believing they faced a stronger force than had actually landed, attacked from the north and south and were repulsed with great loss. With the landings on Empress Augusta Bay, the true nature of the American plan became obvious, and the battalion withdrew to join the forces on Bougainville. As a result of the operation, Choiseul was neutralized; with the Americans on Bouganville, Choiseul was useless.

The bombardment proved ineffective at Bougainsville as well. Preliminary attacks included airstrikes that had been performed for weeks before the landing. Marine aircraft had been hitting the enemy airfields on the island and at nearby locations which could threaten the landing effort. They were aided by Army and Navy planes operating from other islands in the Solomons, including Guadalcanal. Even carrier borne aircraft got into the act, hitting bases on New Britain and New Ireland. The intention was to neutralize Japanese airstrips that were within attacking distance of Empress Augusta Bay. These attacks were largely successful, though some fighters and dive-bombers did delay unloading at the beaches.

On D-day, November 1, the covering fire lasted only 11 minutes, because the Japanese were thought to have few, if any, forces in the immediate vicinity. The first wave of amphibious assault troops landed following a bombing and strafing attack on the landing area. The 3rd and 9th Marines and the Raider Regiment (minus one battalion) carried out the assault, with the 21st Marines and the 37th Infantry Division in reserve. These, about 34,000 men, constituted the I Marine Amphibious Corps.

The transports carrying troops and supplies formed lines off the beach as the barrage progressed. Destroyers bombarded Cape Torokina where intelligence had determined there were enemy emplacements. Ships passed by the cape and let loose with their main batteries. As the transports waited to go ashore, Marine fighters and bombers directed a last-minute attack on the landing area, but in reality they had little effect. Naval historian John A. Lorelli wrote, “The first wave was approaching the beach when the failure of both bombardments was revealed. One bunker behind the southern beaches sheltered a 75mm gun that was put into lethal play by the defenders. The leading boat crew commander became one of the first casualties when his LCVP was blown to bits. The enemy gunners hit thirteen other boats, sinking three. The fire of this gun caused the first wave to become scrambled but did not stop the landing.”

As they moved in, boats carrying the assault troops came under fire from a pair of islands close offshore. A landing party quickly silenced them, but when the assault units approached the beach they were met with heavy fire from small arms, mortars, and artillery. As it turned out, the Japanese had moved in 300 men since the last amphibious scouting mission. These men were well dug in and prepared to offer stiff resistance.

In spite of this opposing fire, the landings were made, though the unexpected resistance and the loss of the boat containing the boat group commander made the assault confused and offline. Many of the units landed far from their assigned positions. Due to these factors, and the landing of the 9th Marines on a severely sloping beach with high surf, the beachhead was very narrow. The extreme density of the jungle also limited the beachhead. The jungle was filled with swampy areas that were very difficult for the assault troops to negotiate. However, by the end of the first day, the Third Amphibious Force had put 14,000 troops and 6,000 tons of supplies ashore. The transports pulled out and minelayers began to lay a minefield off the beach.

Although the landing went relatively smoothly in the center and southern sectors, it was a different story to the north. There was no resistance from Japanese troops, but poor surf and beach conditions disrupted the flow of the landing. Landing craft could not come ashore easily on the steep beaches, and soon the surf was littered with wrecked LCMs and LCVPs. The landing plan was altered accordingly, shifting the northern transports to the south. In spite of Japanese aerial counterstrikes, the transports were offloaded and back at sea by nightfall.

In large part, the operation at Bougainville resembled Guadalcanal. The assault had a limited objective: to capture and defend a strategic airfield site. At the outset, conquest of the entire island was not required. Other points of similarity included the general nature of the terrain and certain of the enemy’s reactions. But there were differences as well. In contrast to Guadalcanal, the Japanese were the ones lacking supplies. Consequently, at Bougainville the result was never in doubt.

Another contrast, and one that determined tactical objectives, was that at Bougainville the Americans would be required to build their own airstrip. This was not because there were none in existence on the island (as a matter of fact, the Japanese had three functioning airstrips). The Japanese fully expected the airstrips to be targets, and they were strongly held. Therefore, strategic surprise was impossible, so it made sense to achieve tactical surprise by attacking where least expected.

In this campaign, though not on Bougainville itself, parachutists played an important part. Four days before the assault on Bougainville began, the Eighth New Zealand Brigade Group launched a parachute assault on the Treasury Islands, southeast of Empress Augusta Bay. This operation was to serve as a feint to distract the enemy from the main effort and to neutralize a potential threat to the Allied line of communications. Although the Allied troops encountered stiff resistance, within two weeks the area was secured.

Six Japanese Cruisers and Two Destroyers Heavily Damaged with a Loss of 10 Planes.

Halsey felt he had enough planes with Kenney’s Papuan bombers, but he worried about the inadequacy of his naval force. Many warships had been lost or damaged in earlier actions in the Central Solomons, and new construction was being earmarked almost entirely for the Mediterranean. What was not was assigned by Nimitz to the Central Pacific thrust. For the assault on Bougainville, Halsey had to rely on Admiral T.S. Wilkinson’s Third Amphibious Force and 12 transports with 11 destroyer escorts.

The expected Japanese cruiser attack on the beachhead came quickly. The Americans were ready and showed how much they had learned since Guadalcanal. U.S. Army reconnaissance planes spotted the force of enemy cruisers and destroyers, and Allied naval forces repulsed them with a flanking attack in the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay.

According to Admiral Halsey’s biographer, two destroyer divisions were detached, “which raced along the enemy’s flanks attacking with torpedoes. At the same time … cruisers, firing their guns, executed a series of 180 degree simultaneous turns, repeatedly crossing the enemy’s T, each time a little closer, and thereby forcing the Japanese into confused retreat.” At dawn the Americans broke off the pursuit and braced for the inevitable air assault that duly came. The Japanese lost 17 planes for two inconsequential hits.

Two days later, on November 4, planes from the Solomons spotted another Japanese force of four destroyers and eight cruisers headed for Rabaul from Truk. The carrier group of Saratoga, reinforced with the light carrier Princeton, could attack the force while it was fueling in Rabaul. This went against the common wisdom that carrier forces should not attack a strong, heavily defended base, but it was necessary to protect the Marines on Bougainville. Along with the land-based aircraft on the island of Vella LaVella, recently captured, the carrier force had air cover and was free to send 100 fighters, dive-bombers, and torpedo planes against the Japanese force that had anchored at Rabaul just two hours before.

The attack was a huge success, damaging six cruisers and two destroyers with a loss of 10 planes. As Halsey remarked upon hearing the report, the results opened “the stops for a funeral dirge for Tojo’s Rabaul.” After three days the beachhead was hardly any deeper, though the troops had encountered no serious resistance since the first day.

The Marines on Bougainville were aided by a number of important factors, not the least of which was the harsh terrain. For one thing, although the swamp they confronted, inhibited expansion of the beachhead, it also was a fine defensive barrier against enemy attempts at dislodgment. Also, the terrain seemed a poor choice for an airstrip, which may go some way to explaining the confused response of the Japanese, who could not fathom Allied intentions on the island and consequently offered only confused and uncertain combat. It was not until the Marines had left and the Seabees and engineers had created a usable base there that the Japanese attempted to dislodge the Allies in any determined way.

The Japanese counterattack in force came in March and was directed at a spot on the American perimeter known as Hill 700. The perimeter was composed of a number of hills and valleys, and Hill 700 was right in the center, towering above the area with a clear view of the airfield. The Americans, aware of an impending Japanese attack, planned accordingly, allowing for a strong reserve force to repulse the Japanese wherever they might make a breakthrough. The massive attack began on March 8, and at one point the Japanese assault partially overran the hill. The attackers were eventually repulsed by 37th Division forces, which inflicted horrendous casualties in recapturing the hill. The Japanese abandoned their effort on March 13.

The seizure of New Britain, the island on which Rabaul lay, began on December 15, 1943. The Sixth Army, under General Walter Krueger, was assigned the task of taking Arawe Peninsula, southeast of Cape Gloucester. Its capture would isolate the western tip of New Britain from Rabaul. It had a small harbor from which control could be extended over the Vitiaz and Dampier Straits, separated New Guinea from New Britain.

Kreuger selected the 112th Cavalry Regiment, along with artillery, engineer, and other supporting units, to conduct the amphibious operation. The 112th had negligible training in the amphibious assault landings, the harbor was infested with coral, and amphibious tractors and tanks had to be used instead of landing craft. Kenney promised air cover, and the Pacific Fleet’s carriers contributed aircraft.

Intelligence reports claimed that Arawe would be only lightly defended, but the 112th Cavalry soon ran into heavy machine-gun fire as they approached the landing sites. Nevertheless, American superiority in firepower quickly forced the Japanese to retreat. By the middle of the afternoon, the 112th had established a foothold. The Japanese began a series of furious air attacks that were to last for several days, concentrating on the American ships supporting the landings. They also brought up reinforcements of infantry to dig in just outside the bridgehead positions. Krueger reinforced the 112th with a Marine tank company and additional infantry. Utilizing armored firepower from Marine tanks, American soldiers forced the Japanese from their trenches.

In the midst of the struggle, a number of firsts had been achieved, according to Barbey’s biographer, “including the first use of tractors, rockets, an LSD, and Australian LSI, LCTs as medical centers, a specially trained naval beach party, landing craft control officers (Barbey’s brainchild), and the employment of carrier aircraft in close support.” In earlier tests, LST’s took three hours to unload; at Arawe they unloaded in less than an hour.

As it was, the fighting took a month. The trenches were not overrun until January 16, at a total cost of 118 Americans killed and 352 wounded.

To complete the security of the right flank of New Guinea, two new bases were needed. At the same time as the fighting raged at Arawe, Krueger launched an operation to seize the airfield at Cape Gloucester on the extreme western tip of New Britain. With airstrips there and in the eastern Solomons, Rabaul could be threatened from the east, west, and south at the same time, effectively neutralizing it. Named Operation Backhander, the assault was a mirror image of Arawe, but prosecuted on a larger scale. The attack on Cape Gloucester required coordination between Whitehead’s air plan and the naval forces of the Southern Pacific Area under the command of Admiral Barbey. The coordinated attack and the concept of preparations used in the invasion were applied to other amphibious operations.

For a week before the invasion, the target was hit with intensive night and day aerial bombardment. Shorter reconnaissance was also carried out on a daily basis to assess the damage and to uncover new targets. With careful planning from naval and coordinated sea patrols, Cape Gloucester was sealed off from Japanese reinforcement and resupply. Naval gunfire and air support during the assault were coordinated and included timely responses to requests by heavy B-17 Flying Fortress bombers. By the time Allied troops landed, the Japanese were worn out.

““From a Hurried Collection of Half-Trained Men and Too Few Ships [the Navy] Acquired More and Better to Work With, but it had Learned to Use It, the Hard Way.”

Yet, according to Barbey, naval bombardment was of only limited usefulness, and must not be considered a panacea. “Naval bombardment,” he wrote, “is very effective against fixed targets, but of little use when firing into a matted rain forest that extends almost to the shoreline. Furthermore, the flat trajectory of naval gunfire was not effective in driving the Japanese out of their pillboxes; aerial bombing of specific targets was better but, unfortunately, we could not count on pinpoint accuracy nor precise timing. Nor was strafing of the beaches with aircraft of much help.”

The landing was to be carried out by the 1st Marine Division, which had not participated in an amphibious operation since Guadalcanal, and the Marines argued with the Navy commander over the number of transports needed. After a three-week air bombardment of the landing area, the Marines were put on the beach by Barbey’s landing craft. A new carrier of offensive firepower, designed by Barbey’s assistant repair officer, also aided the assault. Two LCIs were rigged with rocket launchers, which added plunging firepower and close support for the landing troops.

Krueger landed the troops on an undefended beach about six miles from the airfield in order to outflank the Japanese, who had set up defensive positions around the airstrip. There was little resistance, and the landing and offloading efforts went smoothly. The new practice, first tried on Bougainville, of having preloaded trucks drive from the LSTs to a designated supply area, speeded up the process immeasurably.

With the Japanese already outflanked, the Marines encountered light resistance when assaulting the airfield. However, Japanese resistance stiffened when the Marines tried to clear the jungles to the east. The worst fighting came in a manner that was becoming familiar to the Americans, as they tried to assault a well-camouflaged bunker complex along a stream bank later nicknamed Suicide Creek. For two days, the Marines were thrown back with heavy losses. It was not until Army engineers built a log road through the jungle that tanks could be brought up to blast the Japanese bunkers from point-blank range.

This underscores the importance of American tanks in MacArthur’s offensive designs, which could, to some extent, neutralize Japanese firepower. Log pillboxes and other Japanese defensive positions were often so well built and well hidden that they were impervious to destruction by either ship-or shore-based artillery and had to be assaulted head on. The tank gave the Americans the ability to provide close ground support with superior maneuverability and firepower.

The next step in the march to the Philippines was the assault on the Admiralty Islands, 200 miles northeast of Rabaul. The capture of the Admiralties had been seen early on as a requirement for the isolation of Rabaul. They also were excellent sites for facilities to aid in the approach to the Philippines. The invasion of the Admiralties began on February 28, 1944, with a landing by 1,000 soldiers on the island of Los Negros. MacArthur accompanied the troops. Resistance was light, and at the end of the day’s efforts the invaders had lost two killed and three wounded and had captured an airfield.

By the end of March, after a month of intense fighting and the loss of 326 Americans killed and over a thousand wounded in the Admiralties, the Japanese defenders were no longer a viable fighting force. With the capture of the Admiralties, the Japanese stronghold of Rabaul was surrounded. Bombers pounded Rabaul from dawn to twilight from both Bougainville and Cape Gloucester, cutting supply lines and demolishing installations. The great Japanese base was quickly becoming a liability.

The Japanese were already moving ships and planes out of Rabaul to Truk, their bastion in the Carolines, while digging 100,000 men in to repel the invasion that never came. Cartwheel had been completed, and the Allies carried their offensive toward the Philippines. Perhaps the greatest legacy for the successful campaign was in the experience the commanders and men had gained and in the innovation and honing of triumphant tactics.

In his monograph on the Solomons campaign, Charles Koburger discusses the major turning points in the Pacific War. Naturally, the Battles of Midway and the Coral Sea are at the top of the list. He places the naval Battle of Guadalcanal as even more significant; in fact, it opened the door to the Allied advance in the Solomons and New Guinea.

Koburger also accurately viewed the entire Solomons campaign as vitally important to the war effort, not only in a strategic sense, but in the experience and training that it gave to the Allied armed forces to continue to bring the fight to the Japanese. As he so convincingly puts it, “From a hurried collection of half-trained men and too few ships [the Navy] acquired more and better to work with, but it had learned to use it, the hard way. For the Navy, the whole Solomons was a learning experience. For this, it had paid, in ships, planes, and blood. In the Solomons, the Americans were bloodied, shaking off peacetime attitudes and learning new skills.”

Douglas Sterling is a bookseller who lives in Independence, Kentucky. He has previously written on numerous historical topics.

What the Solomons campaign did do, is that it completed the job of destroying the cream of the IJN’s aviation corps. Midway began the process and the Solomons completed it so thoroughly that by the time of the Mariannas campaign in June of ’44, the IJN’s air forces were so poorly trained and outmatched by the Hellcats and Corsairs that it resulted in the Great Mariannas Turkey Shoot, which essentially knocked the IJN’s carriers out of the war as a serious threat.