by John Brown

Two weeks after Pearl Harbor, coast watcher Cornelius Page, a plantation manager on Tabar Island 20 miles north of New Ireland in the South Pacific, reported by teleradio that Japanese planes were making reconnaissance flights over New Ireland and New Britain. A month later, Japanese marines and troops landed on both Australian-administered islands and quickly overcame the few Australian defenders.

Page kept up a continuous flow of information on the invasions, and with the help of another planter, Jack Talmadge, he organized a spy network from among the local people and reported on the buildup at Rabaul on New Britain. Rabaul was being transformed into a huge base, and airfields were being constructed there and at Kavieng, New Ireland. Page reported for five months, until he and Talmadge were captured and executed.

A Line in the Sea: 1st Marine Division Captures Tulagi

From the base at Rabaul, Japanese forces moved on to the Australian-administered islands of Buka and Bougainville, and then along the double chain of the British Solomon Islands Protectorate, reaching Tulagi in May 1942, where they began building a naval base to complement the excellent anchorage. Coast watchers reported these developments to their headquarters. In late June, coast watchers reported that some Japanese detachments had moved from Tulagi to Guadalcanal and were beginning to construct an airfield on a grassy plain at Lunga Point.

It was then that Allied war planners made the decision to halt Japanese expansion. Tulagi and Guadalcanal must be the limit. The Japanese had to be stopped. Any further advance and their warships and planes would threaten the sea lane between the United States and Australia, where a buildup of American forces and materiel had begun.

On August 7, 1942, a regiment of the 1st Marine Division landed on Tulagi. With the first Marines ashore were two Englishmen, coast watchers Dick Horton and Henry Josselyn. They knew Tulagi well. Before the war both had been district officers in the British administration of the Solomons, and because of their knowledge of the islands the Australian Coast Watcher Organization had loaned them to the Marines as guides and advisers. They were both awarded the Silver Star for their part in the bitter three-day battle for Tulagi.

“Twenty Two Torpedo Bombers Headed Yours”

That same day, August 7, Marines landed at Lunga Point on Guadalcanal, an island about 80 miles long by 30 miles wide. The Japanese, mostly engineering troops and construction workers, offered little resistance and quickly retreated inland. The American transport ships and Navy escort, crowded around the point with their radios tuned to the emergency frequency, heard a warning: “From STO. Twenty four torpedo bombers headed yours.”

The warning came from coast watcher Paul Mason, who was in a hideout with his teleradio on Malabita Hill at the southern end of Japanese-occupied Bougainville overlooking Buin and the Shortland Islands, 350 miles to the north. Before the Japanese came, he had been a planter on the island. His warning gave the ships at Tulagi and Guadalcanal time to raise anchor and disperse with their antiaircraft guns manned. Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters took off from the aircraft carriers Enterprise and Saratoga to wait aloft for the attackers. Only one of the Japanese bombers made it back to base at Rabaul. The rest were shot down by the fighter pilots and antiaircraft gunners or ran out of fuel.

The next day, another coast watcher, Jack Read, came on the air. Before the war he had been a district officer of the Australian administration of Bougainville. Now he was in a hideout at Porapora, overlooking Buka Passage, the channel between Buka Island and the tip of northern Bougainville. “From JER,” he reported, “forty five dive bombers going southeast.” Southeast was toward Guadalcanal.

Later in the day, Paul Mason was on the air again, warning of more Japanese planes on their way to Guadalcanal. In their positions at the north and south ends of Bougainville, an island 125 miles long by about 40 miles wide, the two coast watchers were able to monitor Japanese flight paths from Rabaul on New Britain and Kavieng on New Ireland to Guadalcanal.

The cooperation of coast watchers Horton, Josselyn, Read, Mason, and others during the long battle for Guadalcanal would, at the end of the battle, earn them a commendation from General Alexander Vandegrift, commander of the 1st Marine Division. He called the coast watchers, “Our small band of devoted allies who have contributed so vastly in proportion to their numbers.”

The Civilians of the Australian Coast Watcher Organization

Coast watchers were civilians of the Australian Coast Watcher Organization, a service that began in the years after World War I when a Navy officer in Western Australia, Captain C.J. Clare, created an organization of unpaid members to report on unusual or suspicious happenings along Australia’s 23,000 miles of mostly isolated coastline. The members were outback police, workers on remote cattle and sheep ranches, post and telegraph operators, seamen, missionaries—people from all walks of life who reported to the Naval Intelligence Division in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

When war broke out in Europe in 1939, the Coast Watcher Organization was quickly extended to South Pacific islands under Australian control—Papua and New Guinea, New Britain, New Ireland, Bougainville, the Admiralties, the Trobriands, and by arrangement with the British, to their Solomon Islands Protectorate. Again, members came from all walks of life—district officers and other government officials, planters, trade store owners, missionaries, captains of trading ships and pearling luggers, and gold prospectors.

By the time the Japanese arrived in the South Pacific, the islands in the vast area of sea to Australia’s north and east, both large and small, were dotted with coast watchers. They had no distinguishing badge or insignia and were known only as coast watchers. With the arrival of the Japanese, they were given Australian Navy or military rank or commissioned in the Solomon Islands Defence Force, in the hope that, if captured, their military status would save them from execution as spies.

Coast Watchers’ Eyes on Lunga

At Lunga on Guadalcanal, the Marines worked feverishly on a defensive perimeter around the area while Seabees worked day and night to complete the airfield the Japanese had begun. There were coast watchers at strategic points around Guadalcanal, ready to warn of danger. W.S. Marchant, a former resident commissioner at Tulagi, was now on Malaita with a radio operator named Sexton. Donald Kennedy, a tough, middle-aged New Zealander who had spent most of his life in the islands, was at Segi on the southern coast of New Georgia. Geoffrey Kuper was on Santa Isabel, and W. Forster occupied an outpost on San Cristobal.

On Guadalcanal itself, coast watchers Macfarlan, Hay, and Andresen had reported Japanese progress on the airfield at Lunga and on Japanese ships taking reinforcements and supplies to Tulagi from their position 4,000 feet up on Gold Ridge. They watched the Marines land at Lunga Point and radioed in whatever information they could. “Snowy” Rhoades, a planter who had ridden with an Australian Light Horse regiment in the deserts of the Middle East in World War I, and Schroeder, a frail old man who owned a trade store on Savo Island, who were in hiding at the western end of Guadalcanal, were cut off by Japanese soldiers who had retreated from Lunga in their direction. They began reporting on Japanese activities and movements in their vicinity.

Martin Clemens was at Aola, on the coast 40 miles east of Lunga Point. He rescued the crew of an American bomber that crash-landed nearby, the first of hundreds of aircrew who would be saved by coast watchers. Then, irked by inactivity, he decided he would be of more use at the center of the action and walked though the lines of Japanese retreating from Lunga to join up with the Marines.

In Melbourne, Australia, Lt. Cmdr. Eric Feldt, who headed the Coast Watcher Organization, was convinced the Japanese would counterattack on Guadalcanal. He ordered his deputy, Hugh Mackenzie, to move to Guadalcanal from his station at Noumea, New Caledonia. Mackenzie, a World War I Navy lieutenant and between the wars a captain of schooners and a planter in the islands, was to set up a radio station where messages from coast watchers could be received, decoded, and passed directly to American forces on the spot.

Mackenzie took with him coast watchers Gordon Train; Rayman, a native of New Ireland; and Mr. Eedie, a professional radio operator who volunteered his expertise to set up the radio station. They landed at Lunga a week after the first of the Marines came ashore, and the following day the radio station was in operation in a Japanese dugout at the northwest end of the airfield with a telephone plugged into the military telephone system. The station gave warnings of air raids and received and transmitted intelligence throughout the long battle for Guadalcanal and the advance along the Solomons that followed. (Train was later killed in a U.S. bomber while guiding it to attack a camouflaged Japanese airstrip on an island on which he and his wife had their plantation.)

Despite continuous bombing, shelling, and raging tropical diseases among the men, the airfield at Lunga was completed and named Henderson Field. On August 20, 1942, the first dive-bombers and Grumman Wildcats flew in. The following day, warned by Read and Mason on Bougainville of approaching Japanese aircraft, planes took off from the airfield to intercept them. It was the same again the next day, and many more days to come.

The Rescues of the Coast Watchers

Coast watchers Horton and Josselyn moved from Tulagi to Guadalcanal to help out at the radio station and to guide Marines to points on the island where there were Japanese posts to be wiped out and stragglers to be mopped up. By September, Japanese reinforcements were arriving on the northwest coast to begin the long, grueling land battle for Guadalcanal.

These Japanese landings put coast watchers Rhoades and Schroeder in a very dangerous position, and Mackenzie asked for a rescue attempt. Neither the Marines nor the U.S. Navy could spare anyone for it, so Mackenzie, although he had no authority as he and his coast watchers were there only to receive and pass on information, borrowed a launch and sent Dick Horton around the island to find them.

Horton made the run at night through areas of sea where both American and Japanese craft were operating and would shoot without warning. He brought back Rhoades and Schroeder, 13 missionaries, and a shot-down American airman. Schroeder was a very sick man and was evacuated to Australia. Rhoades carried on at Guadalcanal, but, riddled with malaria, he eventually had to leave for treatment. Mackenzie took a tongue-in-cheek tongue lashing from General Vandegrift for taking unauthorized action.

The Japanese were shelling Lunga at night from their warships at sea and, despite heavy losses, were bombing by day. The coast watchers decided to move the radio station to a deeper and safer dugout a short distance from their present location. The move was made just in time, as shells wiped out the position they had vacated. Coast watchers Macfarlan and Andresen also turned up at the newly located radio station. They had left Hay to continue sending information from the position on Gold Ridge, a task he could handle alone, while they came in to volunteer for postings where they would be of more use. However, Macfarlan’s malaria was so severe he had to be evacuated.

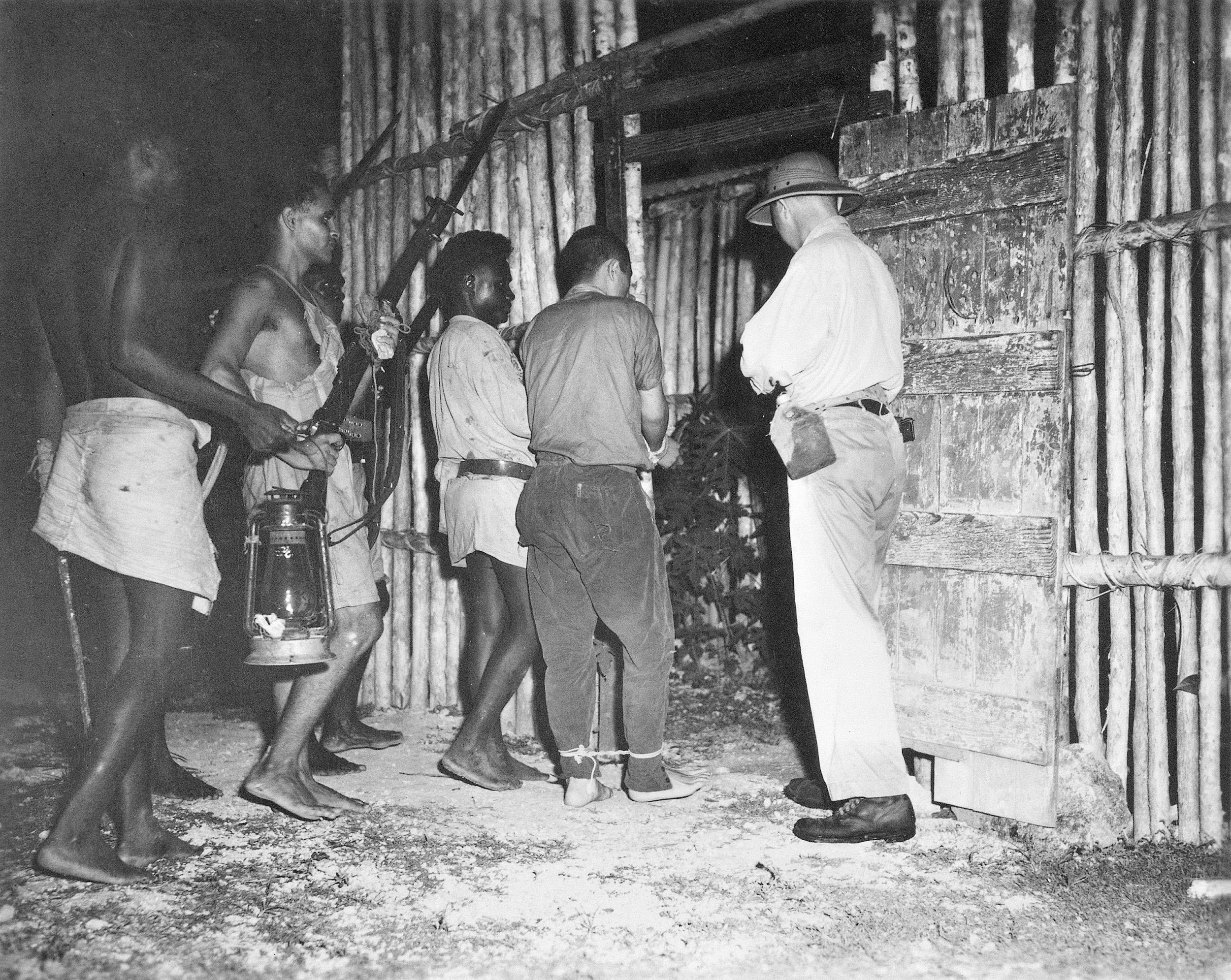

Meanwhile, coast watcher Donald Kennedy at Segi on New Georgia was keeping radio silence. He was completely surrounded by Japanese posts and staging points for barges running reinforcements and supplies to Guadalcanal. They had occupied Viru Harbor, 13 miles from him along the coast, Wickham Anchorage to the south, and Munda on the other side of the island where they were building an airfield and supply base. To keep his position secret, Kennedy taught his native scouts how to use captured Japanese weapons, and they used them to kill any Japanese who came too close to his hideout. They killed 54 and captured others who were held in a stockade at Segi.

In one skirmish with the Japanese, Kennedy was hit in the thigh by a bullet, but he removed it and successfully treated the wound. It did not slow him down. His scouts brought in 22 American airmen and 20 Japanese who had bailed out over New Georgia. As did other coast watchers, Kennedy rewarded the scouts with a bag of rice and a can of meat for each aviator brought in.

The land, sea, and air battles for Guadalcanal had been going on for weeks, and early in November the Japanese began extensive reinforcement of their forces on the island in preparation for an all-out assault. Kennedy was asked to come on the air as, from Segi, he could monitor Japanese shipping to Guadalcanal and time Japanese planes radioed in by Read and Mason on Bougainville to within minutes of their arrival over Guadalcanal. He was also able to report on the U.S. and Japanese airmen he had with him and arrange for them to be picked up by seaplanes. In November, when the Japanese moved a larger force into Wickham Anchorage, he reported it and called for air strikes that sank three cargo ships and a destroyer.

The U.S. submarine Grampus landed coast watchers Josselyn and Frith on Vella Lavella and Seton and Nick Waddell on Choiseul, on either side of the channel known as “The Slot” between the eastern and western islands of the Solomons chain, to report on Japanese shipping movements. Japanese ships and barges were using the channel to run supplies and reinforcements to Guadalcanal, the barges holding up to 120 troopers each. The convoys were coming and going at such a rate that American troops referred to them as the “Tokyo Express.” The coast watchers and their scouts rescued 31 bailed-out or shot-down American airmen, who were then taken out by flying boats. They also rescued 22 Japanese aircrew, although 21 of them had to be killed because they would not surrender.

Pursued by the Japanese

Around northern Bougainville and at Buka Passage there was so much Japanese air and sea activity that Jack Read was having difficulty reporting it. The Australian Army in New Guinea sent him a signaler, Private Sly, to help out. At the southern tip of Bougainville, Japanese troops moved in below the ridge on which Paul Mason had his observation post, bringing with them heavy guns and loads of equipment and supplies. At the same time, more and more ships and barges moved into the anchorage area enclosed by the Shortland Islands. Mason’s reports and the reports of other coast watchers confirmed that the Marines on Guadalcanal would soon be on the receiving end of a massive assault.

The Japanese on Bougainville, aware there were “spies” on the island reporting their activities and movements, decided to flush them out. First, they used tracker dogs, which proved unsuccessful. Then, with radio detection equipment, they fixed both coast watcher observation posts. One hundred men were landed at Buin to take Paul Mason, but he moved out ahead of them and kept going farther into the jungle-covered mountains until the Japanese gave up and returned to their base, whereupon he returned to Buin.

A similar number of Japanese troopers went after Jack Read and Private Sly at Buka Passage. They took off for the mountains with the Japanese at their heels. The following day, high on a mountainside, the sun broke through the rain and far out at sea Read and Sly could see a convoy of 12 troop transports heading in the direction of Guadalcanal. Disregarding the Japanese soldiers somewhere behind them, they set up the teleradio and reported the ships. Later in the day, their native scouts let them know that the Japanese soldiers had given up following them, and they returned to their observation post at Buka Passage.

Calling in Strikes on Japanese Ships

Sixty Japanese ships and barges had assembled within sight of Paul Mason at Buin. They were waiting for the troop transports Read had reported off northern Bougainville. When they arrived and the convoy got underway, heading for Guadalcanal, Mason reported it. American planes and ships attacked the convoy, and the Japanese lost some 6,000 reinforcements intended for Guadalcanal.

On Guadalcanal, coast watcher Mackenzie was wounded but was able to continue his work. Ogilvie, however, was so severely wounded he had to be evacuated. Horton and Andresen, who had been sent to set up an observation post on Russell Island, were brought back to help with the radio station.

By January 1943, the long, bloody battle for Guadalcanal was running down. The Japanese, now aware that they could never recapture the island, began a gradual withdrawal. With this running down and withdrawal, the role of some coast watchers changed. Coast watching activities gave way to scouting and advising in anticipation of an offensive to drive the Japanese back the way they had come. Going in by seaplane, PT boat, or submarine, coast watchers led military and naval technical teams onto islands to check tides and terrain for suitable landing beaches and possible airstrips and supply dump sites. Some gave crash courses for Marines and troops on how to move about on enemy-occupied islands, how to stay alive in the jungle, and how to survive the night when darkness played havoc with men’s nerves.

Dick Horton went to Segi on New Georgia to check on what the Japanese were doing on the island. From Segi he went around the island by canoe to Munda, where he set up an observation post in a tree 2,000 feet up on a mountainside. From this perch he had a magnificent view out to sea and over the Japanese base and airfield below.

Arthur Evans landed on the island of Kolombangara to report on the airfield the Japanese were building there. On one occasion, he saw a Japanese destroyer strike a mine and two other destroyers come to its assistance. He called for an air strike, and all three destroyers were sunk. On another occasion, at night, he saw a flash of light out at sea. He reported it and was told that some PT boats had been involved in an action in the vicinity and the flash was probably the exploding fuel tank of one that had been sunk. He sent his scouts to look for survivors. They brought back the surviving crewmen of PT 109, including the skipper, Lieutenant (j.g.) John F. Kennedy. Evans looked after the sailors until a PT boat got them out. Eighteen years later Evans was invited to the inauguration of John F. Kennedy as the 35th president of the United States.

Clearing Russell and New Georgia With the Army and Marines

Campbell and Andresen scouted Russell Island and found the Japanese had moved out. An American Army division occupied the island and used it for jungle training, while an airfield and a base were constructed for an advance farther up the chain of islands. Andresen was relieved by Hooper so that he could move on to scout Santa Isabel, and Hooper and Campbell set up a radio station to intercept reports from coast watchers and pass on anything of interest to the forces on Russell Island.

When the American advance along the chain began, Rhoades landed on Rendova with the first Marines ashore and led them through plantations he knew well, killing several Japanese in the process. Horton joined him, and they led the Marines to fresh water, pointed out tracks, and located sites to be occupied by various units.

Two weeks before the landings on New Georgia, Donald Kennedy was scouting near Segi, where a major landing would take place, when his scouts reported that half a battalion of Japanese troops were advancing on Segi from their base at Viru Harbor 13 miles to the west. With no hope of containing that number of Japanese, Kennedy radioed for help. Marine Raiders were rushed in aboard two destroyer-transports, the scouts guiding the transports through the reefs to Kennedy, who had lit fires on the beach. For some reason, the Japanese troops stopped short of Segi and returned to Viru Harbor. As Viru Harbor was to be the site of another Marine landing, the Raiders were ordered to attack from behind when the Marine landings began. Kennedy led them on a grueling two-day hike through jungle, swamp, and across chest-deep rivers to get them behind Viru in preparation for their attack.

Corrigan met Marines, who landed north of Munda on New Georgia in June, with scouts and a large number of islanders. They helped carry the Marines’ equipment and supplies inland, along tracks cut out by Corrigan and his islanders, toward the rear of the Japanese at Enogai. During the battle for New Georgia, which lasted until early August, Corrigan and his scouts and islanders carried in supplies to Marines in the front lines and then carried out the wounded. Corrigan was subsequently awarded the Legion of Merit.

From Spotters to Guerrillas

With New Georgia cleared, it was decided to leap-frog the 10,000 Japanese on well-fortified Kolombangara and go for Vella Lavella, an island that Henry Josselyn had reconnoitered with American officers. He had shown them a suitable landing beach, which they accepted. More coast watchers arrived with the first troops to set up a radio station and act as guides.

Parties of American officers arrived on Choiseul to reconnoiter, and each party was met by coast watcher Seton, who left Waddell at their post to keep watch while he led the officers over the island for days. It was then decided to bypass the island and go straight for Bougainville, but, as a diversion, a Marine battalion would raid Choiseul.

When the Marines landed, Seton and his scouts led them to the rear of a number of Japanese positions and were involved in the actions that followed. When the Marines withdrew, Seton, Waddell, and Spencer, who had come in to help, were caught up in a small guerrilla war against Japanese troops who were searching for the Marines they thought were still on the island. More than a hundred Japanese were killed. Between engagements, the coast watchers called in bombers on targets around Choiseul Bay and rescued 23 airmen shot down around the island.

Bougainville: The Dramatic Conclusion of the Coast Watchers’ War

In preparation for the landing at Empress Augusta Bay on Bougainville, two teams of coast watchers and their scouts were landed by the U.S. submarine Guardfish. Robinson, Bridge, Henderson, and scouts were landed at the northern end of the bay, and Keenan, Mackie, McPhee, and scouts at the southern end. Two Marine officers went with the latter team and would meet the troops when they came ashore. When the troops landed, they had with them more coast watchers who set up a radio station to open communication with other coast watchers on Bougainville and nearby islands. More coast watchers came in later to assist in a variety of functions while American forces were on Bougainville.

American forces moved on from Bougainville with the arrival of Australian troops to clear the island of the nearly 40,000 Japanese still there and ready to fight. Paul Mason, who had been hospitalized in Australia, returned to the island to lead local guerrillas against outlying Japanese posts and patrols. They used bows and arrows and spears until he could teach them how to use captured Japanese weapons.

With the Bougainville objective attained, the work of coast watchers in this region ended. They were rewarded with medals and praise and went back to their plantations, trade stores, coastal trading ships, and careers as government officials, asking only that credit be given to the many more involved with them. Without the help of their scouts and loyal islanders who carried their supplies and cumbersome teleradios, the crews of ships and submarines, planes and PT boats who took them to Japanese-occupied islands through enemy infested seas and kept them supplied, and the Marines and GIs who were always quick to respond to any call for help, they would not have been able to operate so successfully.

Admiral William “Bull” Halsey, commander of the Guadalcanal operation, paid tribute to the coast watchers of the Solomons, saying, “The coast watchers saved Guadalcanal and Guadalcanal saved the Pacific.”

John Brown is an expert on the war in the Pacific and a first-time contributor to WWII History. He writes from his home in Minyama, Queensland, Australia.

Join The Conversation

Comments