By Flint Whitlock

When Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany on January 30, 1933, the world changed forever.

Not only was Hitler determined to pay back Germany’s enemies for his country’s defeat during the Great War, but he was also determined to rid Germany and the rest of Europe of persons whom his twisted Aryan ideology believed were “inferior” or “subhuman.”

Almost immediately upon assuming power, Hitler and his minions began instituting a policy of imprisoning personal and political opponents in special holding centers known as Konzentrazionlagern—concentration camps, or “KL” for short.

At first, abandoned factories, warehouses, and even castles were used to incarcerate the Nazis’ enemies—Communists, Social Democrats, dissidents, and anyone who dared to speak out against the government and its policies. Soon others were added to the list of prisoners—outspoken priests and pastors, men guilty of shirking work, even vagrants. The camps initially were to be “re-education centers,” where those who held anti-Nazi views would be taught how to think “correctly.”

By Flint Whitlock

When Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany on January 30, 1933, the world changed forever.

Not only was Hitler determined to pay back Germany’s enemies for his country’s defeat during the Great War, but he was also determined to rid Germany and the rest of Europe of persons whom his twisted Aryan ideology believed were “inferior” or “subhuman.”

Almost immediately upon assuming power, Hitler and his minions began instituting a policy of imprisoning personal and political opponents in special holding centers known as Konzentrazionlagern—concentration camps, or “KL” for short.

At first, abandoned factories, warehouses, and even castles were used to incarcerate the Nazis’ enemies—Communists, Social Democrats, dissidents, and anyone who dared to speak out against the government and its policies. Soon others were added to the list of prisoners—outspoken priests and pastors, men guilty of shirking work, even vagrants. The camps initially were to be “re-education centers,” where those who held anti-Nazi views would be taught how to think “correctly.”

The First Concentration Camps: Nohra and Dachau

The first camp built specifically to hold these persons was constructed in March 1933 at a small Luftwaffe airbase at Nohra, a tiny farming village near Weimar, in the rabidly pro-Nazi state of Thuringia. Consisting of just a few buildings that could hold only 250 prisoners, the camp was soon overflowing; a better and larger solution needed to be found.

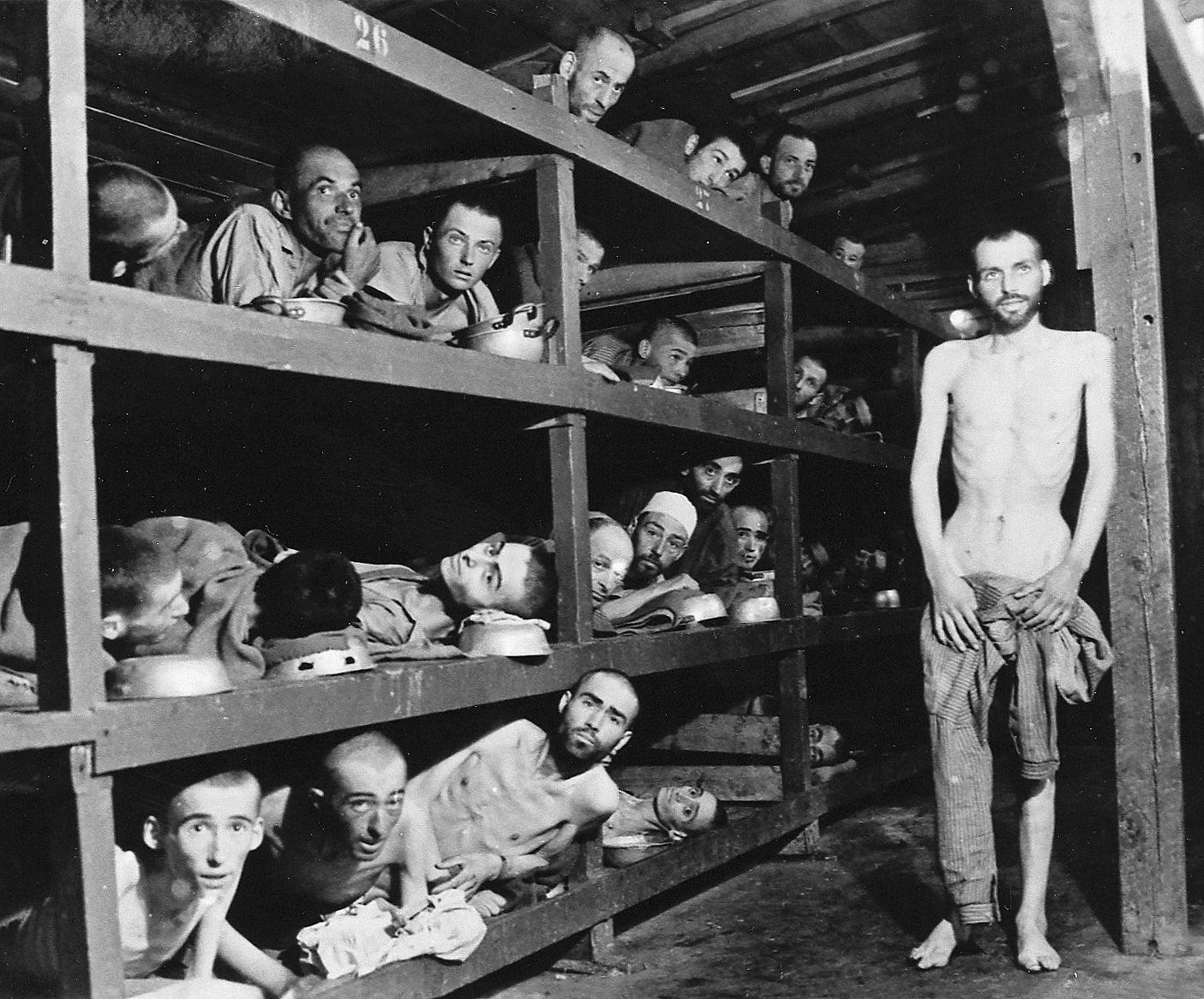

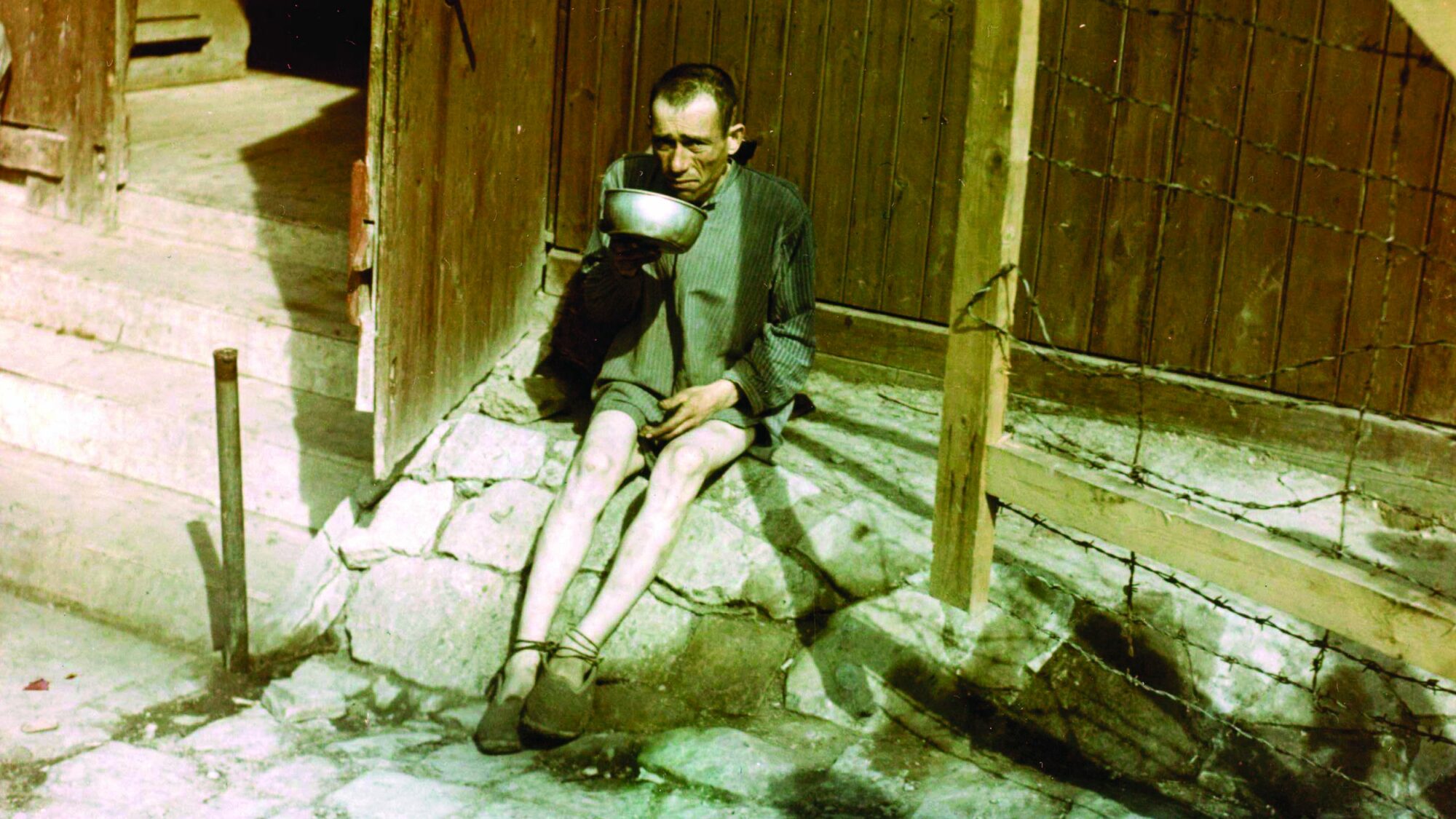

SS head Heinrich Himmler directed SS General Theodor Eiche to devise a more capacious camp, which he did at Dachau, a Munich suburb. Here, adjacent to the sprawling SS compound, dozens of barracks sprang up, surrounded by an electrified barbed wire fence and a high wall to keep out the prying eyes of the neighbors. Here, too, were special facilities for the mistreatment of inmates, and a crematorium for the mass disposal of corpses that, given the harsh treatment and torture, the medical experiments on live subjects, the rampant diseases, and the starvation rations, were becoming more numerous by the day.

It was not long before Jews, Gypsies (also known as Sinti and Roma), Jehovah’s Witnesses, and others also found themselves being arrested without charge and transported to the growing number of camps. Using Eicke’s “Dachau model,” additional camps were created. By the time the war ended, there would be hundreds of main and subcamps, mostly slave-labor camps (Buchenwald, for example, had 174 subcamps).

It was also the concentration camp system that drew little protest from German citizens that emboldened the Nazi regime to go to the extreme and create the death camps—places of mass extermination, primarily but not exclusively of Jews.

Buchenwald, "Beech Forest"

In July 1937, the first buildings of Buchenwald began to be erected atop the Etterberg hill, which dominates the otherwise flat landscape around Weimar. Long a favorite spot for picnickers who enjoyed the views from the Bismarck Tower on the hill’s southern slope and the baroque stateliness of Anna Amelia’s palace on its northern side, the Etterberg held a special place in the hearts of the locals. Atop the hill, it was said, the great German poet and playright Goethe spent many hours beneath the shade of a towering oak tree composing some of his most famous works, including Faust.

Why hasn’t this article been more widely distributed? It needs to be sent to every high school in the country. The government wastes money on so many things; the cost to distribute this is a drop in the bucket! Let everyone know! Let everyone know!!

My great uncle Charlie was there with the 6th Armored Division.