By David Alan Johnson

Lieutenant David C. Richardson spotted the four-engined flying boat silhouetted against the ocean by the late morning sun. The Japanese plane, code-named Emily by the Allies, was only about 20 miles from Richardson’s carrier, USS Saratoga, right where the carrier’s fighter director officer said it would be. As was the usual practice, Richardson split his section of four Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters into two groups—two fighters to attack the enemy reconnaissance aircraft from ahead, and two to come in from behind.

The Emily’s pilot really did not have much of a chance to evade the four fighters. Richardson’s Wildcats made their runs, put several bursts of .50-caliber machine-gun bullets into the big seaplane, and sent it flaming into the sea. When the kill was reported to Saratoga, the news produced a small celebration. It was the first time that a radio-vectored fighter attack from the ship had brought down an enemy aircraft.

Saratoga’s captain, DeWitt C. Ramsey, did not join in the festivities. He was certain that the Emily’s crew had radioed his position back to base and that a Japanese air strike would soon follow. The enemy had been searching for Saratoga and the other two carriers of Task Force 16, Enterprise and Wasp, for the past several days. Now, it looked as though Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander of the Japanese Combined Fleet, had found what he was looking for.

Actually, Captain Ramsey was wrong; the Emily’s crew did not have enough time to radio Saratoga’s position. But it would only be a matter of time before the enemy spotted Task Force 16. That day, August 24, 1942, had been designated by Admiral Yamamoto for the recapture of Guadalcanal. But before this could take place, the American force would have to be found and destroyed.

“A Typhoon of Enemy Reaction”

The American landings on August 7 “generated a typhoon of enemy reaction,” according to U.S. naval historian Samuel Eliot Morrison. Japanese Army, Navy, and air forces were determined that the Marines occupying portions of the island would either be forced to evacuate or annihilated.

The Japanese Navy had already flexed its muscle in the waters around Guadalcanal. In the Battle of Savo Island on August 9, which was one of the most disastrous defeats ever suffered by the U.S. Navy, three American cruisers and one Australian cruiser were sunk, while the Japanese suffered minimal damage. Japanese supply and troop convoys soon began nightly runs down the channel between the islands of the Solomons, known as The Slot. These convoys were dubbed the Tokyo Express by the Americans.

Admiral Yamamoto was confident that the Marines would be forced to surrender by the end of August. An offensive code-named Operation Ka was undertaken on August 16 as a regiment of more than 1,400 army troops along with a contingent of Marines departed Truk in the Caroline Islands bound for Guadalcanal. The three slow transports carrying the troops were escorted by a screen of cruisers and destroyers. A naval task force also departed Truk for Guadalcanal five days after the troop transports. At the heart of the naval force were the carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku, both veterans of both Pearl Harbor and Coral Sea, and the light carrier Ryujo.

According to the Japanese plan, bombers and torpedo planes from the carriers would sink any American aircraft carriers in the Guadalcanal area. Following this, cruisers and destroyers under the command of Rear Admiral Hiroaki Abe, would destroy all U.S. surface warships. After the American naval units had been disposed of, Henderson Field—Guadalcanal’s unsinkable aircraft carrier—would be put out of action. With American naval and air support neutralized, the troops would be put ashore on August 24. Guadalcanal and its airfield would be back in Japanese hands by September.

Allied forces in the Solomons were on the alert for a major Japanese offensive. Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley, commander of American forces in the South Pacific, ordered Task Force 16 to protect Guadalcanal and its sea approaches. The carrier USS Hornet and her escorts left Pearl Harbor for the Solomons on August 17, and the battleships Washington and South Dakota departed the East Coast of the United States for the Pacific. Admiral Ghormley wanted to be well prepared for the coming Japanese offensive. But first, he would have to rely on his reconnaissance to tell him about the enemy’s approach—which ships were coming, and how many.

The two naval forces converged on Guadalcanal. Although both sides strongly suspected the presence of enemy warships in the area, neither had any solid intelligence. Neither Yamamoto nor Ghormley knew the location of his enemy or the makeup of its forces.

Detaching the Wasp from the Fleet

On the morning of August 23, a U.S. Navy Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boat finally made contact, spotting the Japanese troop transports heading southeast toward Guadalcanal. The Japanese carriers and the other warships still had not been located. An air strike was planned to attack the transports as soon as possible. Saratoga sent 37 bombers and torpedo planes to the northwest, and Henderson Field added 23 land-based aircraft an hour and a half later.

But the commander of the transports and their escorts, Rear Admiral Raizo Tanaka, was not about to keep a steady course while the enemy strike approached. He knew that his ships had been spotted and reversed course to the northwest, back toward Truk, at 1 pm, keeping his transports beyond American bomber range.

When Saratoga’s planes arrived where Tanaka was supposed to be, they found nothing but open sea. The planes from Henderson field had no better luck.

Vice Admiral Frank J. Fletcher, commander of Task Force 16, still had no idea where the enemy was or how many aircraft carriers he had. Admiral Fletcher had another problem as well. The carrier Wasp’s screening destroyers were running low on fuel. Because he had no information regarding the Japanese carriers, he reached the conclusion that it would be safe to detach Wasp and her group. Fletcher ordered the carrier south to Efate for a refueling stop, which was a two-day trip.

Fletcher has been severely criticized for this move. By sending Wasp out of the area, he reduced his own strength by 16 aircraft. One-third of the American force would not be positioned to take part in the upcoming battle.

Throughout the night of August 23, the two sides closed with one another. Tanaka’s transport group had reversed course once again and was back on course for Guadalcanal, still undetected by American aircraft. At 9:35 am on the 24th, a Catalina based at Ndeni in the Santa Cruz Islands caught sight of Ryujo and her escorts. The Japanese ships were about 250 miles north of Guadalcanal, steaming southward.

Mistakes on Both Sides

Although the battle had not yet begun, both sides had already made mistakes. Fletcher’s order detaching Wasp turned out to be unnecessary. The logs of all seven U.S. destroyers accompanying the carrier indicated that they had sufficient fuel. Fletcher was by nature a cautious and conservative person and had spent much of his naval career serving aboard cruisers. When he detached Wasp from the task force, his unfamiliarity with carrier operations showed.

On the Japanese side, Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, commander of the Third Fleet, made a similar mistake. Nagumo ordered Ryujo to leave the main fleet and attack Henderson Field with her air group instead of keeping her bombers and torpedo planes for the strike against the American carriers. Nagumo’s order may have been intended to divert the Americans from Shokaku and Zuikaku.

The same plan had been used at the Battle of the Coral Sea in May, when the light carrier Shoho distracted aircraft from the American carriers Lexington and Yorktown away from the main Japanese carrier force—again, Shokaku and Zuikaku. Shoho was sunk, while the big carriers went undetected, although Shokaku was later found and badly damaged.

Admiral Yamamoto has also been criticized for endangering his precious carriers in the defense of such a small landing operation. However, neither the Japanese high command nor Yamamoto considered the retaking of Guadalcanal a small operation. Yamamoto loved to gambling and card games, especially bridge and poker, and was willing to take any risk he saw as calculated.

Yamamoto and Nagumo may have been calculating, but Fletcher was cautious. Even though he knew Ryujo’s position, he hesitated to order an attack against the carrier. He suspected that other enemy carriers were somewhere near Guadalcanal, even though he did not have any definite information. Fletcher had been at Coral Sea and remembered that Shoho had been used as a decoy. Finally, at 1:40 pm, he ordered an air strike launched from Saratoga including 30 Douglas SBD Dauntless dive-bombers and eight Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bombers.

Turning in Circles “Like a Waterbug”

By that time, Ryujo had sent an air strike of her own, six Nakajima Kate bombers escorted by 15 Mitsubishi Zero fighters, to bomb and strafe Henderson Field. They were supposed to have rendezvoused with 24 twin-engined Mitsubishi Betty medium bombers and 14 Zeros from Rabaul, but bad weather intervened and forced the land-based planes to return to base.

Ryujo’s aircraft arrived over Guadalcanal at 1:20 pm, and Marine Wildcats were waiting for them. In the scrambled fight that followed, the Marines lost three Wildcats and two pilots, while three Zeros and four Kates would never return to the fleet. The Zero pilots who survived claimed 15 Wildcats shot down. Actually, Ryujo’s strike had little to show for its effort. Only slight damage had been inflicted on Henderson Field, and this was quickly repaired.

About an hour after its aircraft arrived over Guadalcanal, Ryujo was under attack. Saratoga’s strike group was led by Commander Harry D. Felt, who decided to concentrate all of his dive-bombers on the Japanese carrier. One by one, the bombers opened up their dive flaps and pushed over. Each pilot adjusted his 3-power telescopic sight as his SBD plunged from 14,000 feet to about 1,800 feet, when he reached for the bomb-release lever.

Ryujo was rocked by explosions and near misses. Commander Felt hit the carrier with his own bomb, but marksmanship from the rest of the group was not that impressive. Only three bombs hit their target. After pulling out of their dives, the SBDs found seven Zeros waiting for them. But all of the pilots managed to evade the fighters. None of the bombers was shot down in spite of Japanese claims that eight SBDs had been destroyed.

After the dive-bombers made their escape, the Avengers, under Lieutenant Bruce L. Harwood, began their attack. The torpedo pilots employed anvil tactics—splitting their forces and attacking their target from both bows at the same time so that the carrier would be showing her hull broadside to one of the groups whichever way she turned. Even though smoke from bomb damage made Ryujo difficult to see at times, the six TBFs managed to hit the carrier with one torpedo.

Commander Felt watched the attack from scattered cloud cover and noted that Ryujo turned in fast circles “like a waterbug” while trying to evade the American planes. After he left the area, the carrier slowed to a full stop, listing 20 degrees to starboard. At about 8 pm, she finally rolled over and sank. Most of her crew was rescued by the cruiser Tone. The survivors of the Guadalcanal air strike splashed down near the carrier; their crews were rescued by Ryujo’s destroyers.

Fletcher was glad to hear that one enemy carrier had been knocked out of the battle. He was not absolutely certain that Ryujo had been sunk since Commander Felt led his group back to Saratoga before the carrier capsized. Naval intelligence would not know for certain that Ryujo was lost until 1943.

“Tallyho!”

Fletcher soon received reports from a PBY and from Enterprise’s search planes that two other Japanese carriers had been sighted northeast of Ryujo. One-third of his carrier strength had already been committed when he sent Saratoga’s air group to attack Ryujo. Another third disappeared when Wasp turned south with her destroyers. That left the Enterprise air group available, but at 12:40 pm 16 SBDs and seven TBFs had been sent on the search patrol, which found Shokaku and Zuikaku at about 2:10. All that remained aboard Enterprise were seven Wildcats, 11 SBDs, and seven TBFs.

At about 4:30, Enterprise’s search radar had detected enemy aircraft on an incoming course. The enemy aircraft appeared on their radar screen bearing 320 degrees, distance 88 miles and closing. Radar in 1942 was a good deal more primitive that it would be even a few years later. Enterprise’s radar was not able to give the altitude of the enemy aircraft, and the image remained on the screen for only a few seconds. But after a few quick calculations, they were estimated at about 12,000 feet.

About 10 miles apart, Enterprise and Saratoga put 53 Wildcats into the air. As the fighters strained for altitude, the flight decks were cleared of all dive-bombers and torpedo bombers. These had already been armed and fueled to capacity.

Aboard Saratoga, five Avenger and two Dauntless pilots were preparing to taxi their planes to the forward part of the flight deck, clearing the after deck for the returning air strike. As they sat in their cockpits, the pilots heard a very strange order over the loud speaker instructing them to take off immediately, join up with Enterprise’s group, and attack whatever enemy warships they could find. It was probably the vaguest order they would every receive. They did what they were told, joining Enterprise’s 11 SBDs and seven TBFs. No one had any flight or navigational gear with them, although one pilot did have a chart.

At 4:49, the enemy aircraft reappeared on Enterprise’s radar. They were only 44 miles out by this time. Four sections of Wildcats, which usually consisted of four fighters each, stopped orbiting the task force and flew off to intercept.

Lieutenant A.O. Vorse of Enterprise received the order, “VECTOR THREE TWO ZERO, ANGELS TWELVE, DISTANCE THREE FIVE,” and began climbing. To his right, about 10,000 feet above him, Vorse was able to make out two separate formations of enemy planes. He counted 18 dive-bombers—the fixed-wheel Aichi Vals, with their distinctive spatted undercarriages, were easy to identify in each group, with fighters above and below. At 4:55, he shouted, “Tallyho!” into his radio. At 20,000 feet, with the Vals now 8,000 feet below them, Vorse and his section dove on the enemy bombers.

Donald Runyon and the Tropical Sun

On the way down, the Wildcats were confronted by the Zero fighter cover. Vorse made a side attack on one of the Japanese fighters; a burst from his six .50-caliber machine guns set it on fire. Two other pilots in Vorse’s group also claimed a Zero each. Ensign Francis R. Register also shot down what he claimed to be a Messerschmitt 109 of German manufacture.

The four pilots then headed for Saratoga, which was closer than Enterprise; all of the Wildcats were critically low on fuel. Three of the four made it. Vorse made a smooth landing in the carrier’s wake, out of fuel and ammunition. He was picked up by an escorting destroyer.

Vorse and his group could rightly claim to have done a good day’s work, although shooting down enemy fighters was not really what they were supposed to have done. Getting to the Vals proved to be more difficult than anyone expected. Machinist Donald E. Runyon, also from Enterprise, had no trouble at all. He used the blinding tropical sun to his advantage, making his first attack with the sun behind him. The pilot of the Val did not see Runyon as he approached. A short burst of machine-gun fire shredded the Val’s fuselage; the dive-bomber blew up and fell three miles into the sea.

Runyon used the momentum of his dive to pull back above the Vals, climbing into the sun for a second attack. The second Val did not see him coming either. Once again, the Wildcat’s .50-caliber guns set the enemy aircraft on fire. It splashed into the Pacific about five miles from Enterprise.

Since the strategy of attacking from out of the sun had already worked twice, Runyon decided to try it a third time. As he made his approach toward the unsuspecting enemy dive-bombers, a stream of tracers darted past Runyon’s cockpit—a Zero was firing at him from dead astern. Runyon sideslipped his Wildcat, and the Zero shot past. Now the situation was reversed. The Zero was in front of Runyon. The Zero was an excellent fighter, light and highly maneuverable, but it could not take much punishment. Another short burst from Runyon’s machine guns made the fighter blow up.

Runyon was now below the Vals. He pulled his nose up and brought his guns to bear on a third Val, which fell off in a smoking left turn. Another escorting Zero immediately dove after Runyon. He pulled up to meet the fighter and fired his machine guns for the fifth time in about five minutes. This Zero did not explode, but it did fly off trailing smoke.

“Directly Overhead”

While Runyon was shooting down three Vals and a Zero and damaging another Zero, the other Wildcats of Enterprise and Saratoga were also taking their toll on the approaching enemy. The SBD pilots who had taken part in the Ryujo air strike also found themselves fighting Japanese planes. Lt. Cmdr. L.J. Kirn and his force of 10 SBDs were returning to Saratoga when they came across a formation of four Vals, flying at about 500 feet.

The bomber crews must have been frustrated fighter pilots at heart. They came at the Vals in single file, firing their fixed .50-caliber nose guns, and then flying underneath the surprised enemy. As they passed below the exposed underbellies, the SBD rear gunners opened up with their twin .30-caliber machine guns. Three of the four Vals encountered were shot down, and one was badly damaged.

While the fighter screen did its best to fend off the oncoming Japanese planes, the U.S. ships prepared to defend themselves. Enterprise steamed southeast at 27 knots with her escorts, which included the fast battleship North Carolina, two cruisers, and six destroyers.

At 4:42, Enterprise’s tiny radar plot sent this message: “The enemy planes are directly overhead now.” The fighter screen and Commander Kirn’s 10 SBDs had destroyed as many Vals as they could reach, but about 25 of them managed to evade the defending aircraft. The original Japanese plan was to split and attack both Enterprise and Saratoga, but all of the surviving Vals concentrated on Enterprise.

On Enterprise’s bridge, Captain Arthur C. Davis made a mental note on the performance of the enemy pilots. He was greatly impressed by what he saw, observing, “The dives were steep, estimated at 70 degrees, well executed and absolutely determined.” The gunnery officer on the cruiser Portland did not agree, however. He thought the Vals were pretty good but he had seen better.

“A Steel Umbrella Over the Carrier”

Antiaircraft gunners from the ring of ships around Enterprise did their best to knock down as many attackers as possible. One writer described the barrage as “a steel umbrella over the carrier.” Another said it was “a cloud of fire.” Eight of the Vals were distracted from Enterprise by North Carolina’s volume of fire and decided to go after the battleship instead. All of the attacking Vals missed their mark, although one bomb landed close to the port side. The combined antiaircraft fire accounted for nine dive-bombers, and most of the damage was done by Enterprise’s own gunners.

Aboard Enterprise, gunners watched the lead Japanese bomber grow larger in their sights until even the bomb under its fuselage became visible. Then the Val dropped its bomb and pulled sharply away. The pilot was not lucky—his bomb landed in the sea with a splash, a dud, failing to explode.

Captain Davis ordered Enterprise’s rudder hard over, turning the carrier in a series of violent maneuvers that spoiled the aim of several Japanese pilots, but the Vals continued diving at the carrier in seven-second intervals. At least three of the dive-bombers were blown apart by five-inch shellbursts. Several bombs fell into the sea close to the carrier, throwing fountains of water onto Enterprise’s deck.

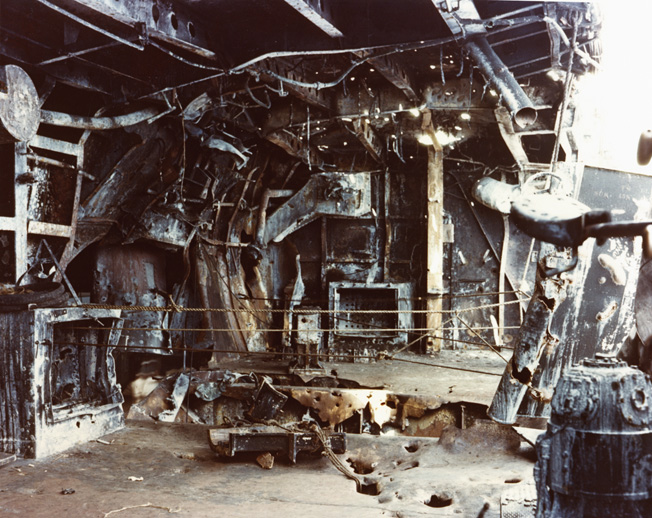

The Enterprise is Hit

The carrier’s biographer wrote, “Neither the skill of her skipper, the aggressiveness of her fighters nor the accuracy of her gunners could save the Big E from such a sustained and well-executed attack.” At 4:44, a bomb hit Enterprise’s flight deck and crashed through the corner of the after elevator. It penetrated three decks before a delayed action fuse set off its 1,000 pounds of high explosives.

“The long, narrow carrier whipped like a musical saw under the hammer blow at her stern,” remembered Commander Edward P. Stafford. “It was like a 60-mile-an-hour truck ride over a rutted country road.” The explosion knocked men off their feet. Gunners were jarred out of their battle stations, causing an unintended pause in the antiaircraft barrage.

The flight deck now had a two-foot bulge as well as a gaping hole. The after elevator would be out of commission until a Navy yard could put it right, and several fires were started. Thirty-five men were killed instantly by the explosion. The blast also ruptured a water main, and the gushing water put out one of the larger fires.

Thirty seconds later, before anyone even had the chance to recover their senses, a second bomb hit. It landed within 15 feet of the first bomb. For the second time in less than a minute, the carrier shook and vibrated. All of the five-inch guns on the starboard quarter were destroyed. Their crews were killed when 40 rounds of powder for the guns blew up.

Enterprise listed slightly to starboard, and thick smoke poured out of the two holes in her flight deck. But she maintained a brisk 27 knots, and her damage control crews went to work putting out her fires, plugging leaks, and restoring power within minutes of the second bomb hit. Pharmacist mates tended the wounds of 95 men before having them moved to sick bay. Only one of these men would die as the result of his wounds.

Three minutes after the first bomb, Enterprise was hit a third time, adjacent Number Two elevator and just aft of the island. This 500-pound bomb was defective, and the explosion is usually described as being of “low order.” It still had enough force to blow a 10-foot hole in the flight deck, damage a few more antiaircraft guns, and put the elevator out of order.

At 4:45, the last of the Vals flew off to the northeast, low over the water with several Wildcats giving chase. The dive-bombers left Enterprise badly holed and belching black smoke. In spite of her list, Enterprise continued at a speed of 24 knots and announced to the fleet that she required no assistance.

One hour after the third bomb hit, Enterprise recovered her aircraft. By 6:21, she had taken 25 of planes back on board. As the 26th made its approach, the carrier began to swing to port. The pilot was waved off and flew off with his wheels down and arrestor hook dangling.

The sharp turn to port was unintentional. One of the three bombs had caused Enterprise’s steering gear to fail. The compartment housing the electric motor that controlled the ship’s rudder had flooded, shorting out the motor. As the helmsman on the carrier’s bridge watched helplessly, the rudder angle indicator swung from full left turn to full right, where it jammed.

Captain Davis tried to steer the ship by using just the engines, an act of desperation that did not work. The carrier kept turning to starboard and nearly collided with the destroyer Balch. Because the rudder was jammed in a full turn, Enterprise could not even be towed.

“LARGE BOGEY TWO SEVEN ZERO, FIFTY MILES”

While her escorts stood anxiously by, Captain Davis slowed Enterprise to 10 knots as a repair crew tried to fix the rudder. Several men did their best to switch control to the standby motor but were overcome by the 170-degree heat inside the compartment. Eventually, Chief Machinist William A. Smith, who was the ship’s expert on the steering motors, succeeded in shifting control to the secondary motor, but only after twice passing out from the heat. Steering was restored to the bridge at 6:39. Enterprise stopped circling and straightened out on a southerly course.

During the time that Smith was desperately trying to recover Enterprise’s steering, radar relayed this message: “LARGE BOGEY TWO SEVEN ZERO, FIFTY MILES.” Shokaku and Zuikaku had launched their second strike. Thirty more Vals were on their way.

The Japanese dive-bombers were on a course that would put them directly overhead in about 15 minutes. Radar watched the blip as it moved to within about 50 miles of the Enterprise task force, and then made a turning that put the enemy planes south. No Wildcats were available to intercept the incoming Vals; all the fighters were low on fuel and ammunition. All at once, the blip reversed course and disappeared. Enterprise had been given an unexpected reprieve.

The leader of the strike had been given Enterprise’s estimated position just before takeoff, and a more accurate position had been sent while the attack group was in the air, but the radio operator apparently did not copy it correctly. The fact that no American fighters were sent to intercept actually helped the American warships. Since fuel was low and there was no sign of the American task force, the Japanese headed for home.

The Aircraft Return

Enterprise enjoyed a reputation as a good luck ship and certainly lived up to its reputation on this day. However, her pilots who were supposed to have joined forces with Saratoga’s dive-bombers and torpedo planes were not as lucky. They could not find the enemy or even each other. Saratoga’s group did manage to locate the seaplane tender Chitose and damaged her with two near misses that caused major flooding.

After a frustrating search for Shokaku and Zuikaku, the leader of the 11 SBDs from Enterprise elected to land at Henderson Field instead of trying to find their carrier in the dark. The Avenger pilots had more fuel to spare and did not turn back as soon. Shortly afterward, one of them caught a glimpse of what appeared to be the long, white wakes of high-speed warships. In the gathering twilight, the torpedo planes dove down to attack the enemy ships.

The wakes turned out to be the sea breaking over Roncador Reef, about 100 miles north of Santa Isabel Island. The pilots jettisoned their torpedoes and set out to find Enterprise. Only one made it safely aboard. The second TBF crashed into the carrier’s island, blocking the flight deck and forcing the others to set down on Saratoga.

By about 10 pm, all of the aircraft that would ever return—American and Japanese—had either flown back to their carriers or landed safely on Guadalcanal. Fletcher wisely decided to retire to the south with Enterprise badly damaged and Wasp now heading north to rejoin the task force. He had no desire to get involved in a night battle. The Japanese advance force had already set a course to intercept the Americans and initiate just such an action. At midnight, with no sign of any American warships, the Japanese reversed course.

Striking the Transport Group

Admiral Tanaka’s transport group was still on course for Guadalcanal and remained undamaged. But a PBY Catalina found the convoy at 2:33 am on August 25 and stayed with it, giving its position at regular intervals. At about 6 am, eight SBDs escorted by eight Wildcats took off from Henderson Field to look for the two Japanese carriers but had no success. When the Wildcats began to run low on fuel, they turned back toward Guadalcanal. The SBDs went on without any fighter cover and accidentally came across Tanaka’s transports.

For some reason, Japanese lookouts thought the approaching dive-bombers were friendly. Tanaka’s flagship, the light cruiser Jintsu, was the first ship to come under attack. After four near misses, the cruiser was hit squarely between her two forward turrets. The bomb flooded the forward magazine, damaged the hull, and knocked Tanaka unconscious.

The SBDs also hit the transport Kinryu Maru, setting her on fire. Another transport, Boston Maru, was damaged by a near miss. After pulling out of their dives, the SBD rear gunners claimed to have shot down two floatplane Zero fighters.

At about 10:15, a flight of eight Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress heavy bombers from Espiritu Santo appeared above the Japanese ships. The destroyer Mutsuki was rescuing men from the stricken Kinryu Maru and dead in the water. When the B-17s unloaded their bombs, at least one scored a direct hit on Mutsuki, blowing her engine room apart. As he was lifted out of the water after his ship sank from under him, Mutsuki’s captain was heard to mutter, “Even the B-17s could make a hit once in a while.”

The same pattern of bombs sprayed another destroyer, Uzuki, with shrapnel from a near miss.

A Resounding US Victory

While Mutsuki was sinking, her sister destroyer, Mochizuki, scuttled the burning Kinryu Maru with a single torpedo. By this time, Combined Fleet headquarters had canceled Operation Ka. The losses suffered the day before, followed by the air attacks of that morning, convinced the high command at Rabaul to call off the landings. Admiral Tanaka, who had shifted his flag to the destroyer Kagero, was ordered to retire to Faisi Harbor in the Shortland Islands.

“The Battle of the Eastern Solomons was undoubtedly an American victory,” wrote historian Richard B. Frank. The Americans lost far fewer men and aircraft than the Japanese. American aircraft losses totaled 25, along with eight pilots and air crewmen. Enterprise was badly damaged and would be out of the war for at least two months while she returned to Pearl Harbor for extensive repairs. The Japanese, on the other hand, lost three ships—Ryujo, Mutsuki, and Kinryu Maru—and 75 aircraft along with their highly trained crews. Japan could not easily replace these losses.

Tanaka’s troop convoy had been turned back. Because the air groups of Shokaku and Zuikaku had been so badly shot up during their attacks on Enterprise, the troops “no longer dared to try a daylight landing” without air cover, observed Morison. The men were taken off the two remaining transports and loaded aboard destroyers for a Tokyo Express night landing three nights later. These troops landed without their heavy equipment, which made them much less effective against the defending Marines.

Japanese senior commanders, including Yamamoto, were well aware that the operation had failed. They had moved south to sink American carriers and put a well-equipped landing force on Guadalcanal but, in spite of their efforts, had conspicuously failed to accomplish either goal.

Even though the Americans won the battle, the commander of Task Force 16 did not come out of it as very heroic, or even as very competent. When Saratoga was torpedoed by the Japanese submarine I-26 on August 31, Fletcher was one of 12 men on board who sustained injuries.

Saratoga would return to the fighting at Guadalcanal, but Fletcher would not. His decision to send Wasp out of the Guadalcanal area just before the battle began ended his career as a combat commander.

“As long as the issue was in doubt, every available carrier aircraft should have been used to protect our tenuous lease on Guadalcanal,” stated Morison. “This is what they were there for.”

The U.S. victory in the Battle of the Eastern Solomons prevented Japanese troops from being put ashore on Guadalcanal in ideal circumstances and softened Japanese resolve to commit further resources to the fight. A Japanese officer on the island noted, “Our plan to capture Guadalcanal came unavoidably to a standstill, owing to the appearance of the enemy striking force.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments