By Charles Whiting

During the second week of July 1944 a young, sharp Lieutenant Goldstein of the 4th Infantry Division’s 22nd Infantry Regiment was told by his boss, Colonel Buck Lanhan, “Expect a special civilian, a big war correspondent is coming to visit us. He can do some good publicity for the 22nd Regiment.”

A little later, the important civilian arrived at the front. Big and burly and wearing a GI helmet, he looked as if he had not shaved since he landed in France and traveled to the 22nd’s sector. Goldstein was eyeing the important civilian’s pocket. Something that looked suspiciously like a grenade was poking out of it, and civilians were not allowed to carry weapons. He was right. Suddenly, the important civilian pulled out a live grenade.

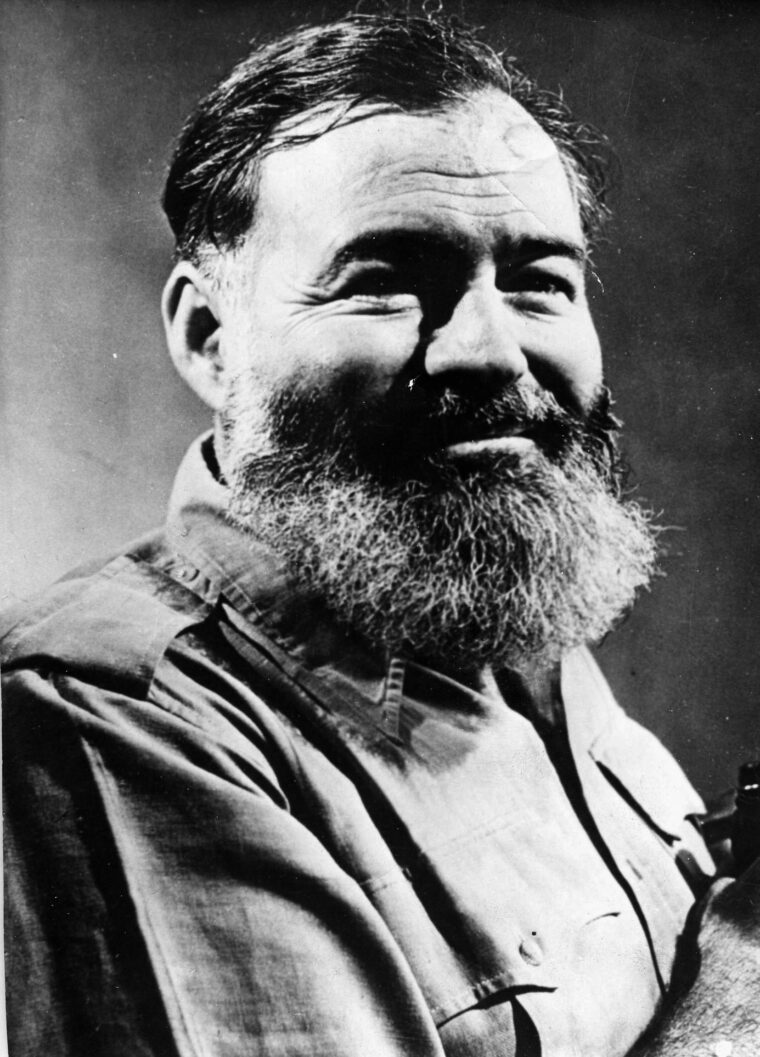

Then, with a grin he put the grenade aside and offered the officer a canteen of some sort of drink. “I took the drink. Then it struck! I shook for a moment, my head throbbing, my eyes popping…. The gulp I had taken from the canteen was pure unadulterated Calvados,” he remembered. Goldstein had just met the man voted America’s most popular writer in August 1944, Ernest Hemingway.

Hemingway’s Favorite Division: The 4th Infantry

Hemingway had arrived at the front to join what he would later call his favorite division, and he had come with a chip on his shoulder. The 45-year-old writer had made his reputation writing about war. Although America had been at war since 1941, he had still not traveled to one of the American fighting fronts. In the meantime, other writers and correspondents were making names for themselves reporting from Europe and the Pacific. In particular, reporter Ernie Pyle, who was eventually killed in the Pacific, was earning high praise in the United States for his reporting from Italy. For some reason Hemingway took a great dislike to Pyle and in a kind of self mockery began to call himself “Ernie Hemorrhoid.”

Now, officially he had come to the front to show the “Great American Public” how the war should really be reported. He would give his readers none of Pyle’s “sentimental guff.” He would show them what war was really like—brutal, unsentimental, red-blooded macho. And his chosen vehicle for this reporting was the unsuspecting 22nd Regiment of the 4th Infantry Division, nicknamed the Ivy Leaguers. He would have plenty of material with which to work. Before the war was over, the Ivy League division would be decimated almost three times, suffering approximately 30,000 casualties.

Not many of those who survived would have ever heard of Ernest Hemingway, but one who did felt that Hemingway was not much better than a cynical fool. The divisional psychiatrist remembered after the war, “I thought he was silly with this machismo thing. I can remember saying to him that if I had his talent and lovely home in Cuba, what the hell would I be doing in this mud? …You see, he was playing soldier. The general was very concerned because Hemingway wanted to go out on infantry patrol, and this meant other soldiers had to be told to guard him and risk themselves to protect him. The general couldn’t tolerate an injury to Hemingway.”

The Last Happy Day

But in the beginning it was easy going for Hemingway’s favorite division and the 22nd Infantry Regiment. In the second week of September 1944, Colonel Lanham’s proud outfit crossed the border river between Belgium and Germany. Opposition was minimal, a mere firefight between the retreating tanks of the 2nd SS Panzer Division and Lanham’s men. Then they entered their first German village, Hemmers, where the villagers had emerged fearfully to welcome their new conquerors from the land across the sea. Hemingway set up his headquarters at the village post office and took command. He ordered all women to kill chickens, and collect potatoes and added to this whatever GI fare he could steal. That night, he gave a “victory dinner” for the brass of the 22nd Regiment. As Lanham recalled, “The food was excellent, the wine plentiful, the comradeship close and warm. All of us were as heady with the taste of victory as we were with the wine. It was a night to put aside the thought of the great West Wall against which we would throw ourselves within the next forty-eight hours. We laughed and drank and told horrendous stories about each other. We all seemed for the moment like minor gods, and Hemingway, presiding at the head of the table, might have been a fatherly Mars delighting in the happiness of his brood.” It was the last happy day. Now the slaughter would commence.

“Let’s Go Get These Krauts”

At 11:30 am on that Thursday morning, the attack on the 22nd took form. At first everything went well, and by 1 pm that day the 3rd Battalion had reached the Siegfried Line bunkers within 900 yards of their first objective, the town of Buchet. But now the men of the German Kampfgruppe (Battle Group) Kuehne, plus the handful of SS men who were assisting them, had begun to react. Enemy machine-gun fire and mortar shells intensified. There was that old, familiar, frightening ripping sound that the 100-pound 88mm shell made when it zipped through the air. A Sherman was hit and jolted to a stop. The crew bailed out rapidly. They knew the 30-ton tank’s bad reputation. They called the Sherman by its derisive nickname, the Ronson. It could ignite just as easily as the well-known cigarette lighter!

The attack began to bog down. Although he was not there, Hemingway described it: “They [the infantry] started coming back down across the field dragging a few wounded and a few limping. You know how they look coming back. Then the tanks started coming back and the TD’s coming back and the men coming back plenty. They couldn’t stay in that bare field and the ones who weren’t hit started yelling for the medicos for those who were hit and you know that excites everybody.”

Captain Howard Blazzard of the 3rd Battalion, who was with Colonel Lanham observing the battle, said, “Sir, I can go out there and kick those bastards in the tail and take that place.” Lanham replied, “You’re an S-3 [operations officer] in a staff function and you stay where you are.”

The two of them remained there for another 15 minutes with more and more wounded drifting back. Blazzard thought gloomily, “We’re going to lose this battle.” Lanham must have thought the same, for, according to Hemingway, he said suddenly, “Let’s get up there. This thing has got to move. Those chickenspits aren’t going to break down this attack.”

The two of them, with Lanham carrying a drawn pistol in his right hand, moved up to a kind of terrace on the hillside where his men were lying down, taking cover. “Let’s go get these Krauts,” he cried. “Let’s kill these chickenspitters. Let’s get up over this hill now and get this place taken!” Two days later, the attack was called off. All along that front the officers of the U.S. V Corps realized they were not going to break through the Siegfrid Line like General S. Patton, commander of the Third Army, had put it, “crap through a goose.” There would be no dash to Germany’s last great natural barrier—the Rhine. The war would not end by Christmas as the pundits back home predicted.

For Hemingway, the time had come to depart from the Ivy Leaguers. He would return to his “headquarters” at Paris’s swank Ritz Hotel and to his current mistress. For the time being, his favorite division would have to look after itself.

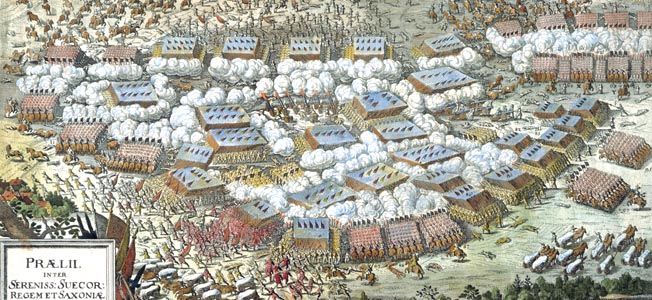

3,000 Yards, 4,500 Casualties

The GIs called the Hürtgen Forest the death factory, though that name never passed the U.S. Army’s censors. It was a great stretch of three wooded areas south of where Hemingway’s favorite division had first entered Germany. The veteran U.S. 9th Division had been the first American formation to attack that dark forest. It had been a sorry experience. It was estimated later that the 9th lost one and a half men for every yard of penetration. In the end, the 9th was pulled out decimated. It had gained 3,000 yards at a cost of 4,500 casualties.

The effort of the 9th was followed by division after division of American troops, most of them lasting only two weeks in that deadly forest before being withdrawn. As Technical Sergeant George Morgan of the 25th Infantry Regiment recalled, “Show me the man who went through the Battle of Hürtgen Forest and who says he never had a feeling of fear, and I’ll show you a liar or a damn fool. You can’t get all of the dead because you can’t find them and they stay there to remind the guys advancing as to what might hit them. You can’t get protection. You can’t see. You can’t get fields of fire. Artillery slashes the trees like a scythe. Everything is angled. You can scarcely walk. Everybody is cold and wet and the mixture of cold rain and sleet kept falling. Then we attack again and soon there is only a handful of old men left.”

At the Ritz Hotel in Paris, Hemingway soon learned that his favorite division was about to enter the Hürtgen Forest. Again, the prospect excited him, and he dragged himself away from the booze, his mistress, and even from Marlene Dietrich who had taken a shine to him.

Dressed in a huge sheepskin coat and carrying the usual canteens filled with liquor, he set off to rejoin the 22nd Infantry. This time his reception was not so enthusiastic. The men knew what they were in for. His friend, Colonel Lanham, could not shake off his mood of depression. He had been ordered to take his main objective, the village of Grosshau, regardless of cost. The night before the attack he sat up all night with Hemingway drinking moodily.

Across the River and Into the Trees

The attack went in, and surprisingly enough the 22nd took its objective—at a cost. Again, the butcher’s bill was high. But Hemingway enjoyed every minute of it. In fact, what he purported to have seen during the Grosshau battle he felt was much too good for his newspaper readers. He decided to keep it for the great novel he would write about World War II called Across the River and Into the Trees.

In it, his Colonel Cantwell (who is really Lanham) talks about what happened there: “We had put an awful lot of white phosphorus on the town (Grasshau) before we got in for good, or whatever you call it. That was the first time I ever saw a German dog eating a roasted German Kraut. Later on I saw a cat working on him, too. It was a hungry cat, quite nice looking, basically. You wouldn’t think a good German cat would eat a good German soldier, would you, Daughter? Or a good German dog eat a good German soldier’s ass which has been roasted by white phosphorus.”

It is not, we can imagine, what the average GI of the 22nd Infantry would like to recall of that battle—if the incident ever took place. It signified too that Hemingway was still regarding the war as some kind of gruesome game from which he could extract cheap thrills and horror. The average GI of Hemingway’s favorite division may well have reflected more that between November 16 and December 3, 1944, Lanham’s 22nd Regiment alone suffered 2,678 casualties out of the original 3,000-man regimental strength. The divisional commander General Raymond O. “Tubby” Barton, explained later, “My magnificent command had virtually ceased to exist.” What did that matter really to Hemingway? In essence, those young men simply provided him with “material” for a novel.

Not Too Ill to Drink

As the battered survivors of the Ivy Leaguers trailed back to nearby Luxembourg to be rested and reformed yet again, Hemingway did what he always did on such occasions. He returned to the Ritz. In December, he fell ill but not seriously enough to stop drinking and skirt chasing. However, as he planned to return to the United States and write his great war novel, he did return to his favorite division yet again. On Saturday, December 16, 1944, he heard from his influential friends at the headquarters of Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower that the Germans had broken through in the Ardennes. Here, some 80,000 Americans, including the Ivy Leaguers, had been struck by some quarter million Germans in a great surprise attack, which would become known as the Battle of the Bulge.

That day, Hemingway called his brother Lester, who was looking after him in Paris, and told him excitedly, “There’s been a complete breakthrough kid … this thing could cost us the works. Their armor is pouring in, they’re taking no prisoners.” So he set off for this new front. But this time he was not fated to report from the immediate action, if he had ever actually done so. His “flu-like” illness grew worse, and his friend Colonel Lanham decreed he should take to his bed in the little Luxembourg village of Rodenhausen.

Here, Hemingway was quartered in the local priest’s house. The priest was supposed to be a Nazi sympathizer, and Hemingway felt it was only his due to take anything of the priest’s he wanted. In particular, he looted the fine wine cellar of this man of the cloth. It was Hemingway’s habit to stagger down from his sickbed to knock off the head of a bottle of wine and drink it. Sometimes he took more care with the bottles, using them as a bed pan and labeling them “schloss Hemingstein.” Once when he was very drunk, it was said he reopened such a bottle and was unpleasantly surprised by the contents.

The End of the War and Hemingway

So, Hemingway’s career at the front in World War II ended. He went back to the States to write his great war novel. At least that was his intention, though he never realized it. As for the survivors and the new boys of the 4th Infantry Division, “the Ivy,” they went on to fight to the bitter end, crossing the whole of Germany and fighting all the time until victory was finally achieved. For them there would be no sojourns in the Ritz and fancy mistresses and well-known writers and artists. For them there would only be the foxhole that might turn out to be their graves as well.

Thus ended Ernest Hemingway’s war in Europe. Years later, the Nobel Prize winner, one of America’s foremost writers, blew his brains out. One wonders what the survivors of his favorite division thought of that.

The late Charles Whiting was a veteran of the British Army during World War II and the author of many books on the topic.

Interesting information! Some extra for a tour I’m preparing in Hürtgen Wald!

Many thanks ??Dirk

My grandfather’ was in the 22nd infantry, at the Battle of the Hurtgen Forest and was shot on December 2nd, 1944.

I live on the brink of the Hürtgenwald, in the city of Düren which was completely erased by British bombers on Nov 16th 1944, at the very start of the Battle of the Huertgenforest. The probable strategic aim was to suppress resupplies to the German forces. Before the war, Düren was one the richest cities of Germany, a cradle of German industrialization and one of the hearts of the steel- and paper-producing industry. The Hoesch company with its rail supply for the German railroad network was literally founded in my backyard.

You can still find, even today, foxholes, trenches, GI shoe soles, battery packs, mortar base plates in the woods, aside of course from the odd dragon teeth line and a few bunkers. The bunkers have all been destroyed, some can still be visited as a big mess (or mass) of steel-enforced, torn and broken concrete, some with visible battle-marks.

One can easily recognize if not relive the intensity of the battle, given the complex shapes and varying elevations of the landscape with its hills, crests, creeks, rivers and deep valleys. Most battle action must have taken place on close-to-medium ranges.

It must have been absolute hell on earth for all men on the battlefield, your fellow GIs and the young Germans who lost their lives, limbs and mental health in the course of the battle. Your camp at least had the solace of having fought for a just cause, the German side was merely fighting an unjust, cruel and pointless war. My generation of fellow Germans has a lot to thank those GIs for.