By Jon Latimer

The Allied landings in Normandy on June 6, 1944, produced a bitter struggle for control of the invasion beachhead. Slowly, the Allies expanded and reinforced, fighting all the time in dense bocage country dominated by hills and hedgerows against an enemy whose skill and determination extracted a high price in men and equipment.

However, the price was at least as high for the defenders. The German Seventh Army had not been expected to face the main effort of the Allies and was itself starved of reinforcements. Thanks to Allied deception, for “seven decisive weeks” as General Omar N. Bradley would later describe them, the 19 divisions of the German Fifteenth Army maintained a fruitless coast watch in the Pas de Calais, barely 200 miles to the north, awaiting an invasion that never came. Seventh Army, meanwhile, was battered by repeated assaults supported by enormous firepower, which steadily whittled away its strength as the Allies gathered strength for a breakout from Normandy into open country.

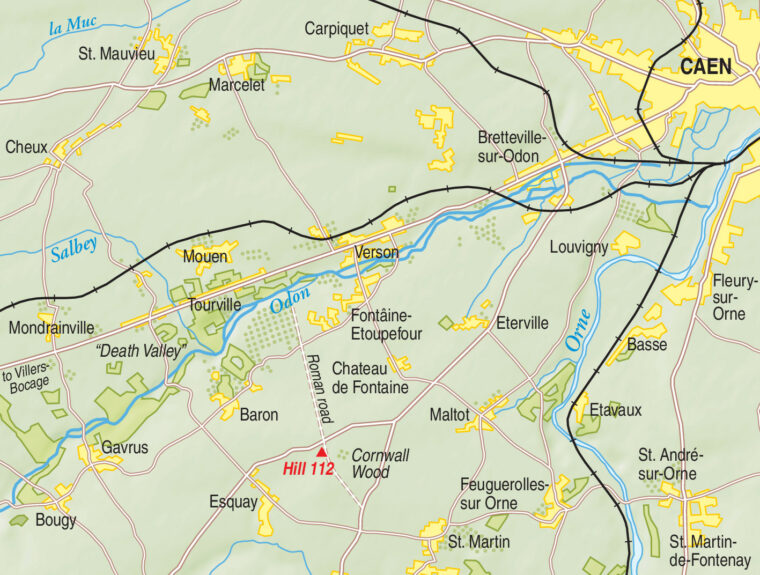

Outside the city of Caen, the River Odon meanders along its valley to join the River Orne east of the city. Along the southern bank lies a low, rolling ridge at whose eastern end the ground rises to form a plateau, the summit being marked on operational maps as Hill 112. The road from Caen to Evrecy crosses the hill east to west, intersected to the north by a track, the straightness of which belies its Roman origins. Standing at the intersection is a calvary, the Croix de Filandriers, and as the track moves southward up to the summit, it reaches a small orchard surrounded by a tree-lined hedge.

Hill 112: The Key to Normandy

German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel declared that whoever held Hill 112 would hold the key to the whole of Normandy. From its summit are commanding views of the surrounding countryside in every direction. Beyond it, the ground is much less cramped, the better to unleash armored forces. It was inevitable that this small feature would become the scene of one of the fiercest battles of the campaign.

The British first drew up to Hill 112 during Operation Epsom, when VIII Corps, supported by more than 700 guns, drove in the outlying German defenses. The Germans held on only by committing the remains of the I SS Panzer Corps. Further operations in the following days led to the 23rd Hussars and 8th Battalion, Rifle Brigade climbing to the summit on June 28. The Hussars were relieved by the 3rd Battalion, Royal Tank Regiment, which together with 8th Rifle Brigade captured the little wood. The German response was to plaster the area with rounds from every available artillery piece. The following day, the 44th Battalion, Royal Tank Regiment joined its comrades on the hill, but at 10 pm that evening, after efforts to consolidate neighboring positions had proved unsuccessful, they were ordered to withdraw.

The men on the summit were shocked, believing they could continue and reach the Orne. But Lt. Gen. Sir Richard O’Connor was deeply concerned that his narrow salient was vulnerable to counterattack from the flanks, and intelligence suggested the immediate threat from the II SS Panzer Corps was extreme. By now, elements of no fewer than six panzer divisions were grouped around VIII Corps, including from east to west the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjügend, the 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler, the 10th SS Panzer Division Frundsberg, the 9th SS Panzer Division Hohenstaufen, the 2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich, and the Panzer Lehr Division of the German Army.

The counterattack had been forestalled by Operation Epsom and was unable to really get going. Starting on June 29, it was over by July 1 as the Germans discovered the difficulties of attacking in the close countryside, filled with concealed antitank guns and infantry armed with the antitank PIAT weapon. Wherever a minor breakthrough was achieved, it would swiftly be pinched out and everything done under the hammer of heavy guns from the Royal Artillery and Royal Navy.

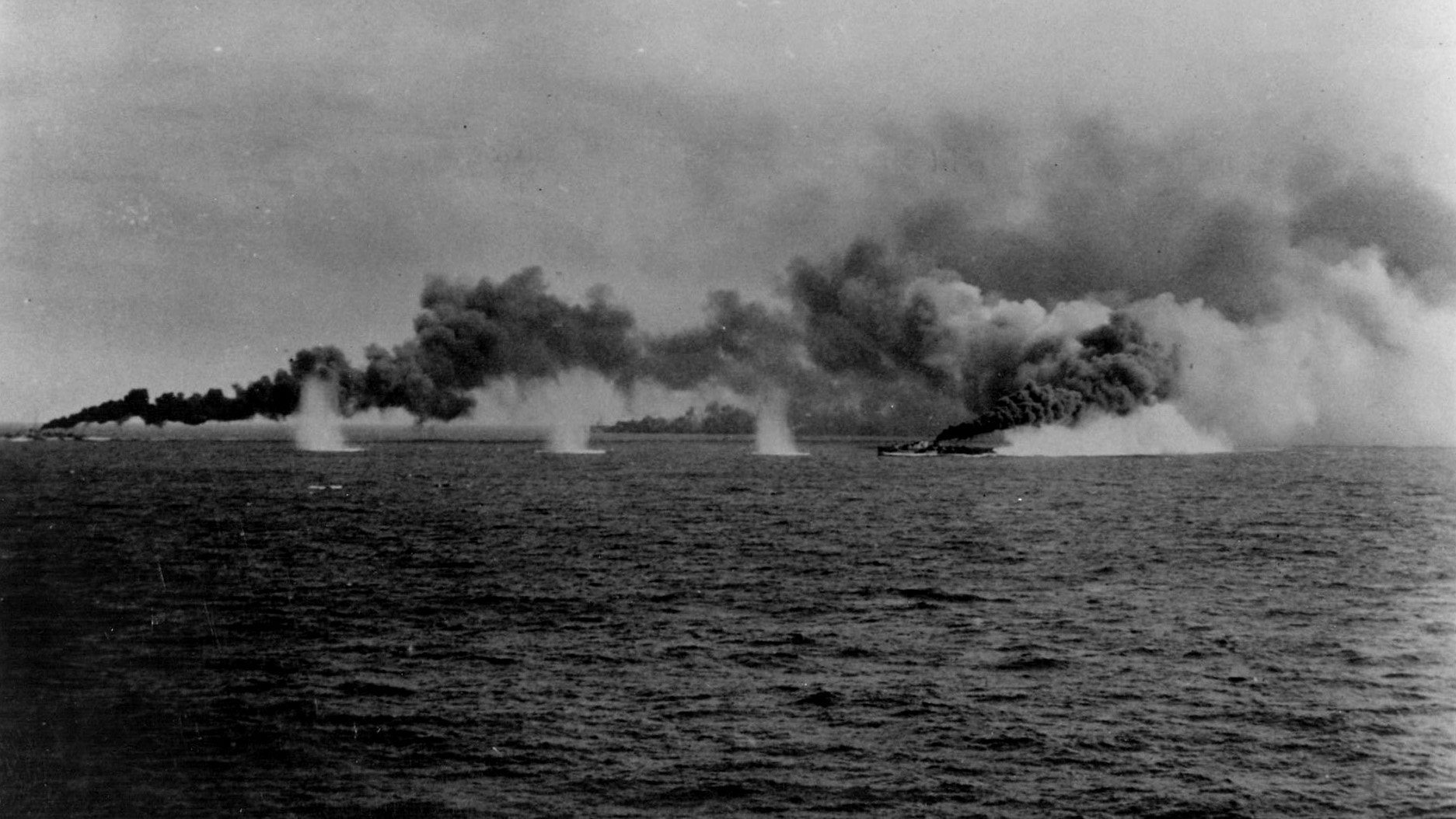

The commander of Seventh Army, SS General Paul Hasser, said, “The murderous fire from naval guns in the Channel and the terrible British artillery destroyed the bulk of our attacking forces in the assembly area.” One regiment counted no fewer than 8,000 incoming rounds in three hours. Casualties had been heavy on both sides, but the British could take comfort from the success of their strategy of pulling the German armor onto their front and whittling it down. The Germans were being forced to hold the line with their armored formations at great cost.

Operation Jupiter and the 43rd Infantry Division

Following an enormous bombing raid, Caen by July 9 was isolated and occupied by British troops, with the exception of its southern suburbs. However, the Americans were finding it difficult to progress to their start line for the eventual breakout, and Das Reich was known to have left the British sector to move opposite the Americans with Panzer Lehr due to move as well. Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, commander of Twenty-First Army Group, decided to reapply the pressure on Hill 112, ordering O’Connor to capture it along with the surrounding villages, and proceed to the Orne beyond. Operation Jupiter would be a four-phase mission conducted by the 43rd (Wessex) Division in its first setpiece battle.

A prewar Territorial formation mostly comprising men from the West Country of England, all the soldiers of the 43rd Infantry were Territorials with the exception of 1st Battalion, Worcestershire Regiment, and each battalion had a strong local character. It had been in long, hard training for years for precisely this moment. It was commanded by one of the most controversial British officers of the period, Maj. Gen. Ivo Thomas. Described by Lt. Gen. Brian Horrocks in his book Corps Commander as “an immensely able divisional commander though a very difficult man,” Thomas may have generated respect but certainly never affection. Nicknamed “Von Thoma” by some, he was called “The Butcher” by others.

For the operation, two brigades of the 4th Armored (equipped with Shermans) and the 31st Tank (equipped with Churchills) Regiments were attached to the 43rd Division, together with field artillery from three other divisions and two army groups of the Royal Artillery (eight regiments of mediums and heavies). Facing them were elements of the Frundsberg and Hitlerjügend panzer divisions. To the west, Hohenstaufen was in the process of being relieved by the 277th Infantry Division, a Wehrmacht formation. The defenders’ divisional artillery was largely intact and supplemented by two brigades of nebelwerfers, the multiple rocket launchers capable of producing a devastating fire.

On the night before Operation Jupiter began, 30 Tiger tanks of SS Schwerepanzerabteilung 102 (102nd SS Heavy Tank Battalion) moved south of Hill 112. Armed with 88mm guns, these monsters could destroy any British tank at long range, while their armor was only susceptible at close quarters. Their presence would prove a crucial factor in what was to come.

Operation Jupiter Begins

Phase I of Operation Jupiter commenced at 5 am on July 10, with the 129th Brigade securing the right flank and the village of Baron. In the center, the 4th Battalion, Somerset Light Infantry (Prince Albert’s) had to advance across some 1,500 yards of open ground supported by the Churchills of the 7th Battalion, Royal Tank Regiment. Closely following a rolling artillery barrage, they unwittingly bypassed a number of German positions so that when the defenders emerged bitter actions followed.

By the time these positions were silenced, the British troops had killed some 100 SS men but suffered crippling casualties in the process. Three out of four rifle company commanders were down, as were most platoon commanders. One company was now commanded by a sergeant. They could not move forward and began to dig in around the crossroads.

Tank action continued around them as the Churchills were engaged by Frundsberg’s Mark IV and Panther medium tanks supported by the 102nd Battalion’s Tigers, forcing the British to retire to hull-down positions. The 4th Somerset Light Infantry’s antitank gunners managed a measure of revenge, however. Their commander, Captain Clifford Perks, recalled, “The corn was so high that we couldn’t use the gun sights. We aimed by guesswork. Soon three German tanks were in flames and a fourth was beating a hasty retreat with smoke pouring out of the turret.” A supporting Achilles tank destroyer also accounted for a Tiger, which had advanced to within 40 yards of battalion headquarters. The German crewmen showed determination to fight to the death and were obliged by a burst from a Sten gun.

Determination and Deception of the Waffen SS

Meanwhile, on the brigade’s left, the 4th Battalion, Wiltshire Regiment (Duke of Edinburgh’s) was learning the nature of fighting SS men. As their regimental historian later noted, “The first appearance of victory was most deceptive. The growing corn, red with poppies, concealed numerous carefully dug positions. These might consist of a single narrow hole containing a desperate man who was quite ready to hide until several hours after the attack had passed over him, and then start sniping. Other and more elaborate positions were deep dugouts in the center of a web of roofed-over crawl trenches leading to weapon pits ready to be manned by Spandau (machine-gun) teams when the leading wave had passed.”

The historian continued, noting that “no inert body could be presumed dead unless it bore the most easily visible wound. Wounded SS men would throw grenades at stretcher-bearers coming up to attend them. Soon the battalion was committed to in-fighting throughout its depth.”

Lieutenant J.P. Williams, going forward to accept the surrender of men, wearing Red Cross brassards, who had raised their hands, was mortally wounded. A stretcher bearer who attended to him was in turn attacked by two wounded panzergrenadiers whom he was forced to kill in self-defense. This merciless, unnecessary incident, repeated wherever the SS were found, generated a grim, determined fury among the British infantry. By 9:30 am, the Wiltshires were digging in on their objective to spend the rest of the day under constant mortar and shell fire. German counterattacks were easily broken up by their supporting artillery.

Casualties Mount

On the left, the 130th Brigade supported by Churchills from the 9th Battalion, Royal Tank Regiment initially made excellent progress as the 5th Battalion, Dorsetshire Regiment signaled the taking of the strongpoint at Château de Fontaine by 6:15. This marked the commencement of the 4th Battalion, Dorsetshire Regiment’s attack on Eterville. The Germans were shaken by the steady flow of soldiers retreating from in front of the 5th Dorsets amid the fearsome British artillery bombardment. The presence of Crocodile flame-throwing tanks of the 141st Battalion, Royal Armored Corps (The Buffs) broke the will of the survivors.

Until this point, the existence of the Crocodiles in Normandy had been kept a closely guarded secret. The only feature distinguishing them from ordinary Churchill tanks was the fuel trailer behind them—until they started spouting 120-yard jets of flame and oily black smoke that consumed everything in their path. Finally, at 8:15 it was the turn of the 7th Battalion, Hampshire Regiment to advance, supported by a squadron of 44th Royal Tank Regiment, passing between the Château de Fontaine and Eterville.

Unknown to anyone in VIII Corps, these troops were heading into a killing ground. In the woods beside the Orne was concealed a panzergrenadier unit from the Leibstandarte, and in a wood near Maltot lay the remnants of the Hitlerjügend’s panzer regiment with some 30 tanks. Furthermore, the commander of Frundsberg had dispatched a strong force to counterattack Maltot, and the two forces converged on the village.

The British force was soon shorn of tank support as these were rapidly knocked out, and the Hampshires attempted to form a perimeter on the crossroads in the center of the village but withdrew to the north to find better fields of fire. The radio link to brigade was destroyed, and two of the artillery observation officers were killed. It took some time to obtain fire support as the enemy closed in. Just as the Germans were poised to break the British line, the shells began to fall among them and broke up their assault. German shelling resumed on what was proving an untenable position, and at 3:30 pm, having lost their commanding officer and 225 other casualties, the Hampshires were given permission to withdraw.

Somehow, as they were pulling back, an order reached the 4th Dorsets and a squadron of the 9th Royal Tank Regiment to reinforce them. For the German tanks now in position around Maltot, it was a shooting gallery. Armored vehicles were blown apart. Twelve of 14 Churchill tanks were knocked out before a squadron of Royal Air Force rocket-firing Hawker Typhoons, observing movement in an area reported clear of friendly troops, added to the carnage. Incredibly, the Dorsets fought their way into Maltot and held on for three hours. When an order to withdraw finally arrived, many men in the forward positions did not receive it and were captured. Only five officers and 70 men were mustered that evening.

With the 130th Brigade battered, Thomas reinforced them with elements of the 214th Brigade, leaving only the 5th Battalion, Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry in reserve. Reinforcements were available from the 46th Brigade, 15th (Scottish) Division, and these proved vital in holding off German counterattacks during the night. However, following a conference at around 3 pm, Thomas decided that the only way to secure Maltot was to capture Hill 112, and there was only the 5th Battalion, Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry available to do it. At the same time, the II SS Panzer Corps was preparing its counterattack with instructions that Eterville might be given up but Hill 112 must not be lost under any circumstances.

Attack, Counterattack

The commanding officer of the Cornishmen was 26-year-old Lt. Col. R.W. James, appointed just two weeks previously. A hasty reconnaissance was followed by a meeting of officers, during which nobody was under any illusion as to the nature of the task before them. Taking the old Roman road as the centerline, the battalion would advance with B and C Companies forward supported by tanks. Unfortunately, these were delayed. At 8:30 pm, the lead infantry, anxious to make use of the cover provided by a preliminary artillery barrage, moved off so that the tanks were forced to tag onto the second wave.

Machine-gun fire made immediate gaps in the attacking lines. A Company deployed to clear the German positions, enabling B (now reduced to a mere 40 men) and C Companies to establish themselves in the wood while the supporting companies began to dig in a ditch bisecting it. James set up a tactical headquarters nearby, and the signalers laid landline back to 4th Somerset’s position. Antitank guns were hurriedly placed on the flanks.

The Germans were quick to react. Their planned counterattack had been delayed by traffic congestion behind the lines, but they put in an immediate assault with what was at hand. This was broken up by a combination of the tank support, artillery concentrations, and the accurate fire of the infantry. As Major Bob Roberts commanding A Company noted, “We had no difficulty repulsing the infantry, the fire discipline being absolutely first class and both companies giving the Boche absolute hell. It was grand to hear the section commanders shouting out their orders: ‘Hold your fire chaps, until you can see the buggers’ eyes.’ It did fearful execution.” Somewhere in the darkness, its supporting infantry pinned down around it, a Panther fell victim to a PIAT.

Battle in the Night

At 11:30 pm, following the accepted British doctrine that tanks could not fight at night, James released his supporting tanks to carefully retire through the uncollected wounded to a forward rallying area. It was something all would regret later. Around midnight, a second German counterattack came in. With tanks raking the woods with machine-gun fire from the flanks, the infantry once more attempted to press home its assault only to be driven off.

Further German attacks were mounted with such regularity that they seemed to merge one into another. Mortar and artillery fire was continual in its efforts to separate the attacking infantry from its armored support. Despite the rain of illumination rounds the difficulty remained for observers to gain a clear view of the hill’s eastern and southern slopes where the Germans were forming up. James solved the problem by personally climbing a tree with a field telephone—a reckless act, but in character for a man who would not ask someone to do something he was not prepared to do himself.

When some Tigers broke into the woods, their vulnerability at night was exposed. Only their strong armor saved them from destruction as they trundled aimlessly about. One halted within 15 yards of battalion headquarters, but the PIAT bomb fired at it failed to explode. However, it quickly took the hint and moved away. Two more wandered into the 4th Wiltshire’s area, overturning a priceless mug of hot tea and drawing a string of oaths from its owner, a Private Pipe, who mistook the offending vehicle for British.

The German tanks were once more engaged with PIATs before trundling into the 4th Somerset area where one of the beasts crushed Captain Clifford Perks’s binoculars and compass without harming the fortunate officer in the bottom of his slit trench. A 17-pounder round struck one of the Tigers under the glare of a 2-inch mortar illumination flare, but once more it survived and retired.

Suddenly, the Tigers were gone. None had taken any offensive action, unable to see clearly in the darkness and risking destruction from the swarming British troops through which they passed. Within the wood, two Tigers almost destroyed each other, one getting off two shots at close range. However, the nervous gunner had failed to adjust his complex optical sights before his target got off a recognition flare. The news that their tanks had penetrated the wood led to a report arriving at German Panzer Group West that the hill was back in their hands, and the Tigers were withdrawn.

“Shoot the First Bastard that Moved”

Later, when the truth became apparent, an even heavier attack was planned for the morning. In the meantime, the Cornishmen were under constant mortar and artillery fire, and from about 3 am, German machine-gun teams added to the crescendo from a stone wall just 100 yards from the forward Cornish trenches.

Requests for assistance from James brought a squadron of the Royal Scots Greys (2nd Dragoons), whose charge was tragically reminiscent of their action at Waterloo more than a century earlier. Their Shermans roared past the flanks of the little wood and silenced the annoying machine gunners, but from the valley below they were exposed to the fire of German armor and five were quickly knocked out. They withdrew to hull-down positions to give what support they could.

At 6:15 am, German counterattacks resumed from the east and south. Panzergrenadiers strongly supported by mortars and artillery were thrown back by British artillery concentrations and the accurate Cornish rifle fire. The Tigers rejoined the attack, with other tanks providing high explosive fire support. The southern portion of the attack was hammered by a particularly violent artillery concentration directed by an airborne British observer. But the Tigers pressed their attack home, taking on the Greys in a one-sided duel before blasting the antitank guns that dared to oppose them and then systematically destroying the Cornish carrier platoon as it attempted to deliver supplies and evacuate the wounded.

During these fierce attacks, James was shot dead in his treetop vantage point. With their popular commander killed and few senior officers still standing, the rumor that an order to withdraw had been received raced forward to the companies. The 4th Somerset,

which had seen the Cornish walking wounded returning through their positions throughout the morning, noted larger groups of men, some running toward the rear. One officer seen trying to halt them could not be understood because part of his lower jaw had been shot away. A sergeant in the 4th Somerset, seeing how jumpy his own men were becoming, threatened to “shoot the first bastard that moved.”

Lieutenant Colonel C.G. Lipscomb, commanding the 4th Somerset, could see that the Cornishmen were not panicking. After repelling at least 12 separate attacks, they were simply confused, exhausted, and near the end of their physical endurance. One soldier recalled of Lt. Col. Lipscomb, “Lippy was outstanding in many difficult situations and none more so than when the remnants of 5th DCLI after a terrible time in Cornwall Wood on Hill 112, came back into our positions.” Quietly, Lipscomb rallied them and divided them into company groups, none more than a platoon strong, before being led back to the wood to reoccupy their positions. The few panzergrenadiers that had infiltrated the wood in their absence had certainly had enough and quickly surrendered.

For a while, the Cornishmen were left in relatively undisturbed possession of the wood. At 2 pm, however, increased enemy fire heralded another attack. This time it came from Maltot supported by assault guns. The remaining antitank guns on this side of the hill could not be depressed enough to fire, and so, under cover of a smoke screen, a 17-pounder was manhandled forward until it could engage the Germans. It knocked out three assault guns before succumbing itself.

Four German assault guns remained active, and these were to prove too much for the tattered remnants on the hill. By now, Roberts had been wounded and his command reduced to around 100 men. Runners were sent to urge the brigade commander to either relieve or withdraw them.

No answer was received. Fry, now the senior officer, was faced with the terrible dilemma of saving the remains of the battalion or being overrun. Since the wood was about to fall into German hands anyway, he ordered a smokescreen and pulled his survivors and all the wounded they could carry back to a position behind the 4th Somerset Light Infantry. The Cornishmen had suffered 320 casualties in and around the wood. Only one of these had been taken prisoner. Effectively, Operation Jupiter had come to an end.

Outcome of Operation Jupiter

Although the British had failed to secure the summit of Hill 112, they at least succeeded in denying it to the Germans, and it remained a no-man’s-land. More important, they had pinned the German armor once more to the front and prevented its movement westward. Fighting erupted once more on July 15 and continued spasmodically for another two weeks. At the same time, with the summit masked by intense high explosives and smoke, the 43rd, 15th, and 53rd (Welsh) Divisions all launched heavy raids on neighboring villages, which succeeded in provoking fierce counterattacks that further wore down the German armor.

The start of Montgomery’s Operation Goodwood on July 18 further convinced the Germans that the breakout would be aimed to the east of Caen. The actual breakout, codenamed Operation Cobra, was launched on July 25, achieving complete success. Replacements arrived. The 4th Somerset Light Infantry needed 19 officers and 479 other ranks. Among them was Sydney Jary, who was told, “Your life expectancy from the day you join the battalion will be precisely three weeks.”

Having been severely mauled in the difficult battle for Hill 112, the II SS Panzer Corps was finally withdrawn from the area on the night of August 3, its divisions reduced to mere battalion-sized battlegroups with a handful of tanks between them. They were sent to the Netherlands to refit near Arnhem.

A few nights later, the Assault Pioneer Platoon of the 5th Duke of Cornwall Light Infantry erected a sign showing the regimental badge, a light infantry bugle surmounted by a Roman corona muralis, and the words CORNWALL HILL, JULY 10TH-11TH 1944. Many regiments felt they had a claim to that unholy acre of land, but none would take the sign down, and all refer to the hill in their own regimental histories as Cornwall Hill. A granite memorial to the 43rd (Wessex) Division has since been placed on the same site.

Jon Latimer is the author of several books on World War II. His most recent work is Burma: The Forgotten War. He lives, writes, and teaches in Great Britain.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments