By Bill Warnock

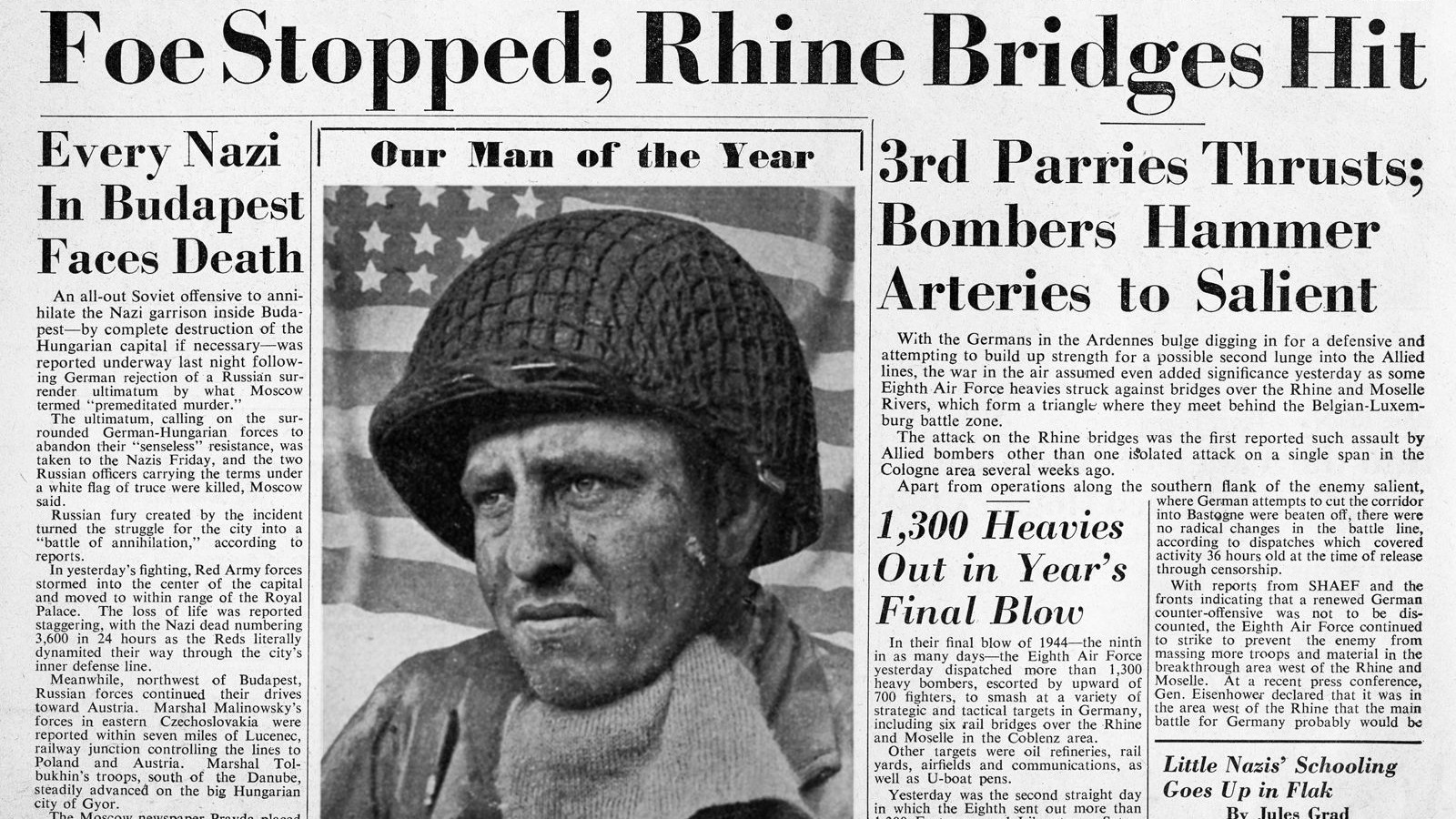

During the closing days of 1944, editors at the London edition of Stars and Stripes decided to select a frontline GI as “Our Man of the Year.”

Staff members sorted through hundreds of photographs before finding the right face. They finally came across one that conveyed all the misery of the frontline soldier and all the courage, too. The soldier’s glassy eyes had an absent, faraway look. His stubbled chin, unwashed face, and mud-spattered uniform added to the appearance of a man who had endured a gnawing diet of terror and death.

The editors decided to withhold all personal information, intending for the picture to represent all GI Joes. The art department retouched the image by painting out the tank helmet worn by the soldier and replacing it with a steel helmet. The editors felt the tank helmet would suggest only the armored force, and the steel helmet would better represent all American soldiers.

On New Year’s Day 1945, the picture appeared on the newspaper’s front page. The gravity of the photograph revealed so much about the soldier, yet it left Stars and Stripes readers wanting to know more.

Letters poured into the London office of the newspaper. The respondents demanded more information about the anonymous soldier. One soldier expressed the overall sentiment, “We’ve got names, and we want ’em used.”

In response to the barrage of mail, one of the editors went back through the hundreds of pictures and found a photo caption with the name Hobart Drew, a tank driver from Bloomingdale, New Jersey. His name subsequently appeared in a follow-up article.

Newspapers in the United States jumped on the story, interviewed Drew’s mother, and published pictures of him taken before he departed for European battlefields. But Stars and Stripes had made a mistake. The editor had pulled the wrong photo caption. The face actually belonged to a tank commander named John H. Parks.

One other fact remained unknown to anyone at the newspaper. The soldier’s unit had reported him missing in action.

This is his story.

Of Humble Origin

John Henry Parks was of humble origin. His mother, Ella, had immigrated to the United States at age 21, leaving behind her family in Longton, England. She arrived at Ellis Island in 1910 with only a suitcase full of belongings. The young woman had a maternal uncle living in Cleveland, Ohio, and she traveled there to live with his family.

Ella married, divorced, and remarried during World War I. Her second husband was Mathew Parks, a man 30 years her senior and a widower. The couple wed in 1917, less than one month before Ella gave birth to a baby girl they named Marie. The family lived in a tiny apartment above a pool hall. Mathew, or “Massey” as everyone called him, was an ex-sailor who now worked as a night watchman at a local factory.

Ella gave birth to John on March 10, 1919, at City Hospital in Cleveland. The expanding family moved out of the apartment and into a small wood frame house that Massey rented. It sat in a working class neighborhood alongside the foundries and steel mills in the treeless industrial valley of the Cuyahoga River.

The family expanded again on Christmas Eve 1920, when Ella bore a third child, Lester. They moved to another home in the same neighborhood but eventually departed for Michigan, home state of John’s father.

As a small child, John watched his parents’ marriage crumble. His dad often struck his mom, blackening her eyes. On several occasions he choked her and knocked her to the floor, all the while cursing her. John’s parents separated in March 1925. His father drifted to Detroit where he took up residence in a hotel. By year end he had stopped contributing to the financial support of his three children. John’s mother lost no time moving on and already had a new man in her life.

She and her kids took up residence with Milo Harness, an illiterate trapper and farm laborer from Mill Creek, Indiana. The tiny community lay in the Hoosier backcountry bordering Michigan. The place took its name from the black ribbon of water that snaked through the marshes west of town.

Milo rented a shanty on three acres, most of it swamp and cattails. He and John’s mother had their first child there in late 1926, a boy. The couple later married and had a daughter.

The economic calamity of the Great Depression soon visited havoc on John and his family. Unable to support five children, his mother and stepfather reluctantly cast off the three Parks children, sending them to Brightside orphanage near Plymouth, Indiana. Brightside, also known as the Julia E. Work Training School, included 226 acres of farmland, a schoolhouse, administration building, dormitories for the children, and all the necessary outbuildings for livestock and farm equipment. Boys learned farming skills. Girls learned housekeeping essentials, everything from sewing to milking cows.

In March 1930, John’s father died at age 70. His children had not seen their absentee father in five years.

John’s older sister, Marie, had by now left Brightside, tearfully departing her brothers to live with a foster family. John too left Brightside to live with a foster family. He moved in with Evans Garrard and his wife Coraellene, who owned a farm near Hamlet, Indiana. The couple had no children of their own. John attended Union Township High School and played on the school’s basketball team. He never graduated from Union High, completing only two years.

The teenager eventually returned to his mother in Mill Creek as did his brother Lester. While living there, John worked on the Leo Stephani farm in nearby Kingsbury. He also operated Mill Creek’s only pool room, a hole-in-the-wall joint where he sold bottled beer. The young proprietor drank an occasional beer with his customers and smoked Camels. He also played a harmonica and could imitate train whistles.

John never owned an automobile. He purchased a blue Indian motorcycle and a cloth riding hat. Town residents often saw him on the bike, zooming along the dusty roads that crisscrossed the rolling hills around Mill Creek. At age 20 he lost a finger while helping cut lumber at a sawmill in Kingsbury. He came home with his left hand bandaged and caught his mother’s wrath.

That same year, John’s older sister married, the first of his siblings to wed. He became an uncle two years later when his sister gave birth to a baby girl. John had no family plans and no girlfriends. As he often said, “I have a mother and two sisters. That’s enough.”

Leaving the Factory for the Army

In 1941, he landed a job at the newly constructed Kingsbury Ordnance Plant, a sprawling facility that produced ammunition of almost every caliber and employed workers from all over northern Indiana and points elsewhere. Despite his missing finger and war-industry essential job, John never sought a draft deferment, though eligible. He entered the Army on January 31, 1942, less than two months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

His decision to waive a deferment caught his family by surprise. His little sister said to him, “You crazy fool!” He just grinned.

John reported to the armed forces induction station at Fort Benjamin Harrison near Indianapolis. He underwent a physical, and the doctor judged him fit for active duty. After a short furlough to return home and set his affairs in order, he reported back to Benjamin Harrison and received uniforms, service shoes, dog tags, and a battery of inoculations. He and a trainload of other fledgling troops then rode south to the Armored Force Replacement Training Center at Fort Knox, Kentucky.

The men began basic training. The first couple of weeks introduced them to the profession of arms and taught them how to look and behave like soldiers. The remainder of the training focused on the fundamentals of operating and maintaining armored vehicles. John had ample experience with farm tractors and mechanical equipment, and he made a natural tank crewman, the very reason the Army had sent him there.

Toward the end of the training period, a crowd gathered around typewritten papers pinned to a bulletin board. As the men edged their way forward to see them, John read that he and many of his fellow trainees had orders to report to the 4th Armored Division at Pine Camp, New York. The group journeyed there by train. At 7 pm on April 15, 1942, John and 16 other men became members of Company E, 37th Armored Regiment.

During the summer months, John earned two promotions in quick succession, rising to private first class and then corporal. In early autumn, the 4th Armored Division moved to the Cumberland Mountains of Tennessee to participate in large-scale maneuvers. Mock battles helped the men master the instruments of killing.

John and other men received time off when the maneuvers ended in November. Later that month, they returned to duty and, along with the rest of their unit, boarded Pullman cars bound for the Desert Training Center at Camp Young, California. There, amid shimmering waves of heat, the tank crews ranged across the dead and defeated Mojave Desert landscape. Sandstorms, frigid nights, and blazing daytime temperatures challenged their fighting skills as did a lack of vegetation for shade and camouflage.

The calendar flipped to 1943, and halfway into the new year orders came for the 4th Armored Division to pack up and depart for Camp Bowie, Texas. By now John held the rank of technician fourth grade and was a tank driver.

During the first couple of months at Bowie, his company commander doled out furloughs. John received 15 days, and he traveled home to Indiana. He returned to duty on September 9, the very day his armored regiment disbanded. Portions of it formed the 37th Tank Battalion. John’s Company E became Company B of the new battalion. Camp Bowie remained his duty station until December when the 4th Armored moved to Camp Myles Standish near Taunton, Massachusetts, a staging area for units headed overseas. All tanks and trucks remained behind in Texas. New ones waited abroad.

Just after Christmas, John and the men of Company B journeyed to the Boston port of embarkation. Weighed down with backpacks, bedrolls, and overstuffed duffel bags, John and his buddies filed up the narrow gangplank of the USS Santa Paula. This converted cruise ship would carry them across the North Atlantic.

Landing on Utah Beach

On January 10, 1944, the Santa Paula docked at Swansea, Wales. John and the soldiers of his company (five officers and 111 enlisted men) squeezed into undersized train cars and rode 100 miles through the night to Devizes, England, a small city complete with a castle. The men took quarters outside the city in wooden huts at Waller Barracks. Their new turf lay on the fringe of the Salisbury Plain, the great chalk downs that served as the main peacetime maneuver area for the British Army.

Company B procured new tanks and trucks from an ordnance depot at nearby Tidworth Barracks. Most of the armor consisted of older model M4 Sherman medium tanks, each packing a stumpy 75mm cannon and powered by a Wright Whirlwind aircraft engine.

One member of the company painted artwork and nicknames on all the tanks, each name beginning with the letter B, signifying Company B. John was the driver of “Brooklyn Boy,” commanded by Staff Sergeant James N. Farese from Jersey City, New Jersey. Farese, known as Gentleman Jim, served as platoon sergeant for the Third Platoon. Besides John, three other men crewed the tank. Ernest O. Ritland of Radcliff, Iowa, served as the assistant driver and operated the bow machine gun. Sherman Troxell and Harry A. Bordner manned the 75mm cannon. Like John, Troxell hailed from Indiana.

John learned the feel of Brooklyn Boy’s clutch, accelerator pedal, and two steering levers. He got to know the tank just as in bygone days the cavalryman knew his horse. John and the entire 37th Tank Battalion drilled from dawn to dark on the Salisbury Plain. The countryside reverberated with their thunder. The tank crews persisted no matter how foggy the weather or how hard the skies poured rain.

Razor sharp and keyed up, the men received orders to depart Devizes and relocate to a bivouac area a dozen miles away. Three days after their arrival, the Normandy invasion began. They sat on the sidelines living in pup tents. The wait lasted until July 7, when the 37th Tank Battalion moved to Camp D-12, a short drive from Portland Harbor. Two days later Company B motored to the harbor in two groups and rolled aboard four U.S. Navy LCTs (landing craft, tank). The vessels sailed after dark, bound for the sandy shores of France.

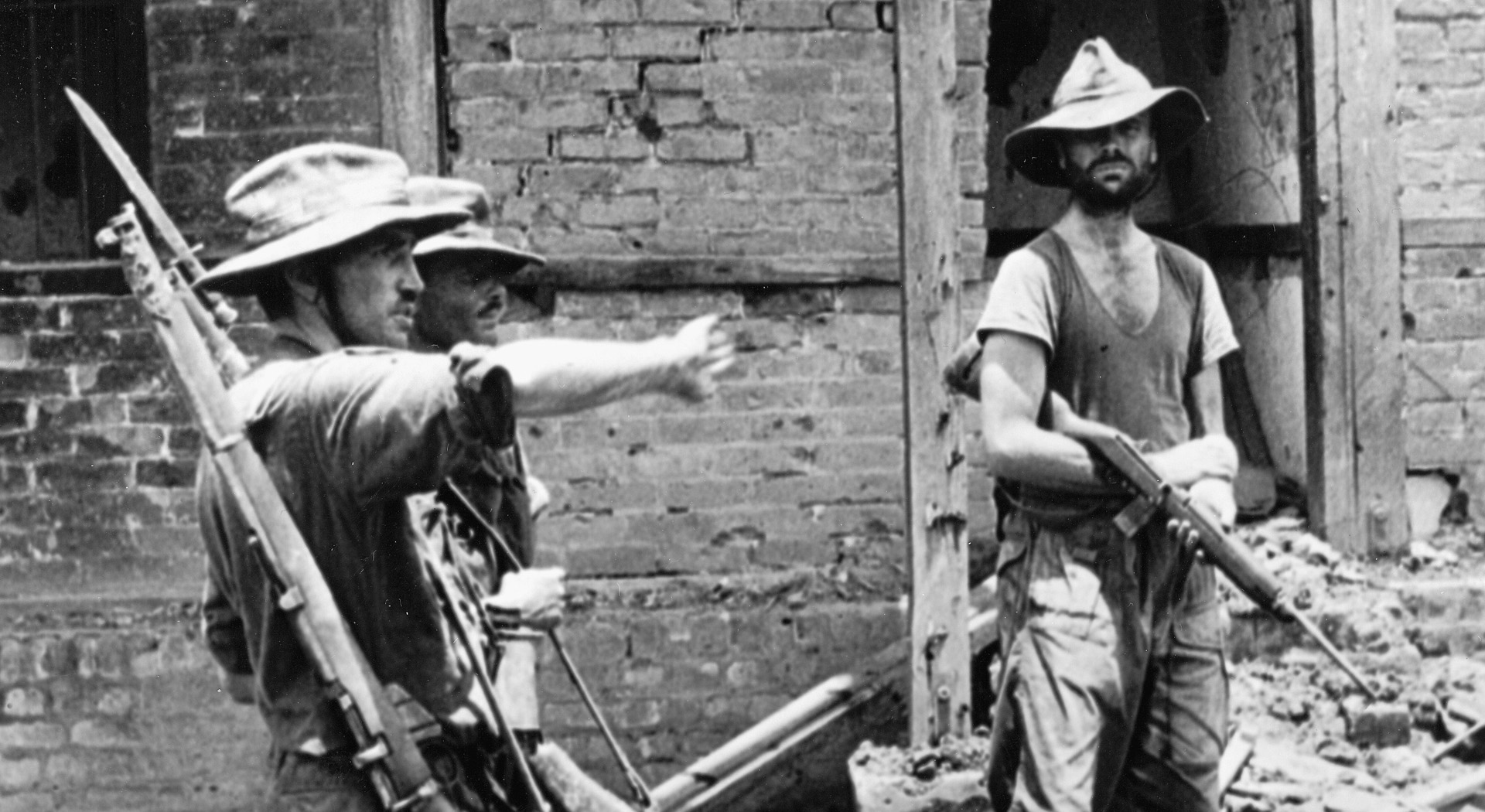

On July 11, 1944, John Parks and the crew of Brooklyn Boy landed at Utah Beach. They and the other tanks crews initially sat idle on the Cotentin Peninsula, waiting for their part in a massive attack designed to catapult American forces from the peninsula. The attack erupted on the Germans during the final week of July and within days reduced them to defeat and retreat.

John’s company broke out of the Cotentin and raced toward the Brittany Peninsula along with the rest of the 4th Armored Division. As they stormed ahead, the attackers left a trail of German corpses bloating in the summer sun. The hard-driving Americans kept their enemy off balance, unable to strike back. They side slipped the Germans and slashed through them, all the while driving to reach the sea and cut off the peninsula.

Rivers of Blood

Near the coast on August 7, John came upon an improbable sight: enemy horse cavalry. This force belonged to Ost-Reiter-Abteilung 281, a White Russian unit fighting for the Germans. The riders dismounted their steeds and stampeded them toward the oncoming tanks. The road became a slaughterhouse as horses collided head-on with the tanks. Animals fell, bellowing and writhing. Tank treads ground fallen horses into pulp and produced rivers of blood. Amid the butchery, enemy bullets killed a tank commander and seriously wounded the lieutenant in charge of 2nd Platoon.

Unimpeded by the carnage, the armored vehicles rolled on toward the port city of Lorient. Near the city, the tank company and the entire 4th Armored Division received new orders. They wheeled around and blitzed headlong into the interior of France. John and his comrades liberated territory as fast as tanks could travel, rolling through cities and villages, one after another.

Dust churned up by the long file of tanks coated John’s face, invaded his nostrils, and choked him. At night he pressed ahead with nothing for guidance but two winking blackout lights on the tank ahead. Sleepiness fogged his brain. He strained to hold the tank on course, both hands gripping the steering levers. Day and night, the powerful airplane engine mounted at the rear of his vehicle created a steady roar, which drowned out all conversation.

Sherman vs Panzer

The drive across the French countryside continued at a relentless and exhausting pace. The enemy could not be allowed to catch his breath. On the last day of August, John’s company pushed forward despite a torrential downpour. The tanks vaulted the Meuse River on a bridge the enemy had no time to destroy. The advance ended a day later when the tanks ran dry of gasoline. Germany lay only a day’s drive ahead.

After a 700-mile rampage across France, the 4th Armored Division had outpaced its supply chain. The tank crews succumbed to their own success. The crews rested and had their first hot showers since July. More than a week passed before they received fuel and returned to the road and crossed the Moselle River.

But the Germans had regrouped during the gasoline shortage. They stiffened up in the hills east of the Moselle and punched back at their attackers. The first jab occurred on September 18.

John entered the fray the next morning when a dozen enemy tanks, all factory-new Mark V Panthers with high-velocity 75mm cannon, threatened to overrun a 4th Armored command post. John’s company stormed toward the intruders, guns blazing. The enemy battlewagons withdrew, unscathed, over a hill. One of them returned fire at long range and knocked out an American tank, killing a man inside. John’s company girded itself for an enemy assault, but nothing followed.

Later that day, the company helped track down the Panthers, which had gathered in a low area. John and the others flanked the German tanks and charged downhill toward them. The enemy crewmen had their eyes and guns turned toward another threat.

Hearts pounding and brows sweating, John and his colleagues ripped through the enemy formation, gunning down nine Panthers at close range. The others fled. John’s group suffered no losses. They remained in the area until nighttime dropped its black veil over the battlefield. The nocturnal sky glowed with the wild orange flames of burning German tanks.

Tank-versus-tank combat continued for days afterward. The Americans shredded two panzer brigades, testimony to the skill of crewmen like John Parks and the ability of their leaders to outthink the enemy and turn circumstances to their advantage. The tank duel became known as the Battle of Arracourt.

A Campaign of Mud and Blood

After the win at Arracourt, another gasoline shortage hobbled the victorious forces. Amid the shortage, John’s unit took time to rest, reorganize, and perform vehicle maintenance. John received a promotion to sergeant on October 17 and became a tank commander in 2nd Platoon. Privates Herman R. Coffy of Carrollton, Ohio, and Edward H. Clark of South Portland, Maine, joined the sergeant’s crew as gunner and loader, respectively. Coffy and Clark had arrived earlier that month as replacements. Two other less recent replacements also joined the crew. Private Joseph E. Caisey of Chelsea, Massachusetts, became the driver, and Private Harold A. Kleintrop of Allentown, Pennsylvania, became the assistant driver and bow gunner.

John’s old tank commander, Jim Farese, accepted a battlefield commission and became a second lieutenant. He had assumed temporary leadership of 2nd Platoon prior to Arracourt. Now he took permanent charge of the platoon.

Slanting gusts of rain fell while John’s outfit camped near Serres, a French hamlet. When the tank soldiers returned to battle in November, their vehicles churned spongy fields and pastures into mud. The morass frequently barred passage, restricting the Americans to road surfaces. This meant operating on a front no wider than the lead tank.

The GIs carried the war into the Franco-German borderland. This region of divided loyalties marked the cultural boundary where Latin Europe and Germanic Europe collided. John discovered French towns with German sounding names like Obreck, Rodalbe, and Durkaster.

He and his comrades rumbled forward and sometimes backward against persistent German shelling and counterattacks. These attacks wrecked tanks and snuffed out American lives and kept the Graves Registration troops busy putting up wooden crosses. November became a campaign of mud and blood, but John and his crew dodged injury.

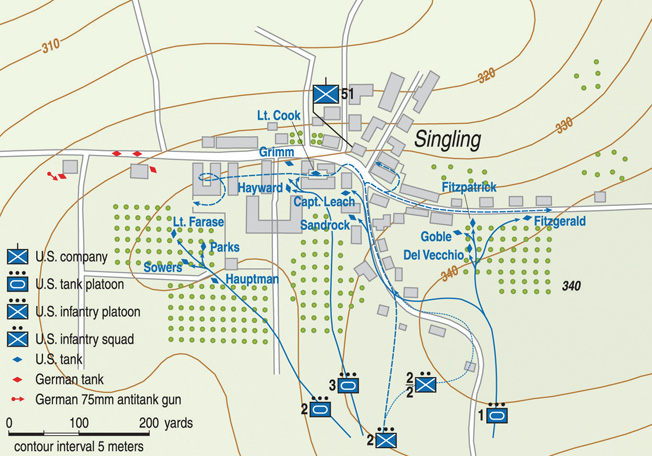

As the weather grew colder, the rains turned to sleet and flurries. By the first of December, John’s company had moved to a rest area near Mittersheim, France. Three days later, the tank crewmen returned to the front line. Quiet prevailed until the unit joined an attack into enemy-infested terrain. One day into the operation, John’s company received orders for an impromptu assault against a hilltop village named Singling.

Assault on Singling

The tanks lumbered uphill toward the village, firing as they moved. American artillery hit the place, too. Fires burned in the town. On the village outskirts, John’s tank swung into an apple orchard and followed Farese’s vehicle. The tanks wove between the leafless trees as they neared the crest of the hill. Farese led by about 50 yards and drew enemy fire the instant he reached the crest. An armor-piercing shell drilled his machine. The German gunner polished off his handiwork with two more rounds. These hammering blows killed Farese and one other crew member. Three survivors bailed out.

John backed away from the crest, as did another tank to his side. A third tank joined them in the orchard, all of them unable to push beyond the crest. Elsewhere, tanks and armored infantry penetrated Singling and slugged it out house to house with the Germans. Enemy armor in the form of assault guns posed the toughest obstacle.

The tanks in the orchard stayed put until receiving a radio call to attack the assault guns. The tanks motored out of the orchard, but antitank fire thwarted their mission, and they returned to the grove of fruit trees.

German artillerymen pummeled the orchard in hopes of smashing the tanks. John and his comrades backed into a cabbage patch and avoided the drubbing. But minutes later an armor-piercing shell caromed off the crest of the hill and penetrated Sergeant Joseph B. Hauptman’s tank, killing a man inside. The other crew members, including Hauptman, abandoned the wrecked machine.

The surviving tanks received instructions to move to the shelter of a building at the edge of town and await further orders. Panther tanks joined the fray as the enemy intensified pressure on Singling. As the fight continued, another tank unit relieved John’s company. The German squeeze tightened and forced the Americans to abandon their foothold in the village. All U.S. forces withdrew after dark.

The abortive effort to capture Singling resulted in the destruction of four tanks from John’s company, two from his platoon. The losses carried a greater human toll, seven men wounded and five names in Death’s ledger. The company had never suffered that many dead in one day.

Respite in Mittersheim

The tank crews fell back to Schmittviller and a couple of days later returned to the rest area at Mittersheim. Shorthanded, the unit reshuffled tank crewmen since no replacements were available. John gave up his driver and assistant driver and gained one man in return, Technician Fifth Grade Russell K. Holland. The former Chicago taxi driver and longtime veteran of the unit had been injured at Singling when enemy shells knocked out his tank and killed or wounded the entire crew. He had not required hospitalization and took over as John’s driver.

During the respite at Mittersheim, a team of Signal Corps photographers arrived on December 10, 1944, to capture images of the battle-worn tankers. One of the Signal Corps visitors, Private First Class Donald R. Ornitz, carried a bulky Speed Graphic camera. The short, slender cameraman traipsed through the mud taking pictures. Raised in Los Angeles, the 24-year-old had become enthralled with photography as a teenager and never considered anything else for a career. In 1942, he voluntarily joined the Army to serve as a photographer.

At Mittersheim, many tank crewmen he encountered looked straight at him but seemed unaware of his presence. He sometimes found it impossible to read age on their pale, dirty faces. Wrapped in weariness, these tired soldiers wanted nothing more than to lie back and live.

Ornitz approached John and framed a portrait through the camera’s peep-sight. The young photographer had a gift for knowing just when to squeeze the shutter release. He caught all the agonies of war crystallized in John’s eyes.

After the Signal Corps team departed, the soldiers had more visitors. Two Army historians arrived on December 12. They intended to write a detailed study of the battle at Singling. John and 13 other men reported to the company command post where the historians questioned them.

The tank crews spent another three days at Mittersheim before heading back to the front, eventually reaching a German village called Walsheim. The armor helped garrison the recently captured town. It was the company’s first excursion into Germany. As the men waited for attack orders, enemy shells claimed one life and injured half a dozen other men. Then, inexplicably, John’s company received an urgent directive to return to Mittersheim.

The Drive to Bastogne

Details slowly emerged. German forces had cracked open the front line to the north and surged into the Ardennes region of Belgium and Luxembourg. Against this onslaught, numerous American units had fallen back in retreat, some in a horror of disarray. Other units had ceased to exist, bowled over like tenpins. The titanic scale of the German operation became clearer with each passing hour. In an effort to help blunt the attack, the 4th Armored Division received instructions to disengage from its present area and rush north.

John’s company pulled out of Mittersheim at 8:30 am on December 20, 1944, and motored all day and well into the night. The march halted after 120 miles. The company spent the next day conducting vehicle maintenance while higher headquarters formulated an attack plan. The 4th Armored pulled a formidable assignment: break through to encircled U.S. forces at the crossroads town of Bastogne, Belgium.

On December 22, John’s company drove 13 miles north and sat in reserve while other elements of the 4th began the push toward Bastogne.

Laagered in a field, the tanks sat idle as snowflakes swirled down upon them. The temperature hovered around the freezing point as the snow continued to fall. John and his four-man crew spent the night in their tank, a 75mm M4 built by the Baldwin Locomotive Works.

Before sunrise on December 23, the tank crews fired up their engines and plowed through the snow along the main road to Bastogne. Surrounded by a gray curtain of fog, these veteran soldiers once more headed out to pit themselves against the enemy. They had orders to capture a town in Luxembourg called Bigonville.

The reconnaissance platoon of the 37th Tank Battalion led the way in jeeps and a half-track. John and his comrades followed behind. They had only seven tanks and an assault gun. Armored infantry half-tracks trailed them.

Ice covered the road beneath the snow, and the tank tracks would not bite into the slick surface. Vehicles in the armored column fishtailed left and right as they struggled for traction. The column turned onto a secondary road and slid across the border into Luxembourg and the village of Perlé, which had fallen into American hands the previous day.

Clash at Holtz

The most direct route to Bigonville lay over open high ground. The reconnaissance platoon avoided that route and followed a more protected route that cut through a large forest. After passing through Perlé, the column descended ever so slowly into a valley. Tanks skated out of control on the ice. John’s driver, Russell Holland, put one track into the earthen shoulder of the road to gain better traction. The column reached the valley bottom and then inched uphill. Nobody had ever experienced driving this treacherous.

At the top of the hill, the column reached the outskirts of Holtz, a drab-looking hamlet already under American control. Daylight now filtered in through the fog. The recon men guided the column toward the large forest. They navigated a snowy road that passed over rolling hills. Near the forest, the head of the column reached a group of parked jeeps and armored cars. The recon men pulled off the road and joined the vehicle gathering. The leader of the recon team saluted John’s company commander, Captain James H. Leach, and waved the tanks onward. They were on their own.

The company commander’s radio crackled. “Enemy at Blue!” said the voice on the other end. An artillery spotter aircraft had sighted Germans on the other side of the forest at a crossroads called Flatzbourhof (designated Phase Line Blue).

John’s company pushed into the forest and battled the icy road. Snow on the road bore fresh track impressions from a German tank. He and the others would soon be fighting more than weather conditions.

The young man with sergeant’s stripes on his sleeve stood in the turret of his tank, his body exposed from the waist up. Tank commanders in the 37th always stood exposed that way. Their battalion commander, the bold and brilliant Creighton Abrams, insisted that no tank commander could perform his job without seeing what was going on all around, and that required looking out of the turret instead of using periscopes. Abrams himself did so in battle. Turret hatches “rusted open” in the 37th, the men used to say. The advantages of all around visibility and quick target acquisition outweighed the risks.

Fresh snow clung to the tree limbs. The morning fog had burned off, and the day shone blue and bright. Each tank commander stood bolt upright, jaws clenched, eyes darting. The road beneath them, like so many previous roads, promised to lead somewhere they would want to forget.

The company commander led the way and emerged first from the forest. He pulled his tank off the road and surveyed the terrain ahead. Flatzbourhof consisted of a café, two grubby farmhouses, a sawmill and attached home, and a tiny railroad station. The captain also observed a block of spruce trees no bigger than a football field. The stand of conifers occupied the highest terrain point.

The captain soon caught glimpses of ghostly looking figures dashing around in white camouflage, the enemy for certain.

Jimmie Leach deployed his tanks. He sent John’s tank to the left of the road followed by Staff Sergeant Bernard K. Sowers, Staff Sergeant John J. Fitzpatrick, and Sergeant Emil DelVecchio. And to the right, Leach sent First Lieutenant Robert M. Cook and Staff Sergeant Max V. Morphew. The tanks maneuvered across snow-covered fields. Enemy eyes had long since spotted them, and the Germans responded with small-arms fire.

Bullets beat a tattoo against the hull of John’s tank. Much of the firing emanated from the block of spruce trees. John and his crew pressed ahead. Holland circumvented a swampy area and drove toward the spruce trees, but a railroad embankment blocked the way. They could not climb it, but Parks spied a solution. He directed the driver to follow a narrow country lane that passed over the embankment at a graded crossing.

The tank lumbered over the crossing and into a pasture. Nobody followed John over the embankment. The other tanks pulled alongside it and gave covering fire as John advanced alone. Rows of soldierly spruce trees stood in tight ranks, and, among them, German paratroopers crouched low and fired at John. His gun crew, Herman Coffy and Edward Clark, answered back with high explosive shells. Enemy shots chimed off the turret.

John’s tank crept closer and closer to the trees. The sergeant suddenly fell into his tank, landing on the turret seat and on Coffy’s backside. “What’s the matter with you?” Coffy thought. He turned and saw a large hole above John’s right eye. The sergeant had a blank stare, his eyes wider than in life. He was dead.

Coffy reacted without panic or grief and pushed the lifeless body off him. Blood and butchery had become too commonplace to provoke emotion, and in the pitch of battle there was no time for it. Coffy took command of the tank. The driver threw the vehicle into reverse and backtracked.

At the edge of the pasture, near the railroad crossing, the tank shuddered. Fire and white-hot steel blew through the crew compartment. Coffy had the presence of mind to bail out through the turret hatch, and Holland sprang out through his driver’s hatch. Both men narrowly dodged German bullets. Clark never emerged.

Another enemy shot (perhaps from a Panzerschreck, the German bazooka) slammed into the tank’s right sponson. The tank interior became an orange chamber of fire, a crematorium.

The two survivors clambered into a nearby ditch and ducked down. Both men had injuries and were bleeding. Everybody in John’s company looked in the direction of his tank and saw a black column of smoke smeared against the blue sky.

After the battle, Jimmie Leach searched John’s destroyed vehicle. A formal report later described the investigation: “Captain James H. Leach, commanding officer of Company B, inspected inside of the tank by flashlight but could see no bodies, but the tank was completely burned. Nothing but ashes remained inside the hull.”

Unable to locate bodies, Leach followed procedure and reported John and Ed Clark missing, though he knew both men had almost certainly perished. Coffy and Holland had verbally reported the fatalities. As for Coffy and Holland themselves, aid men evacuated the pair from Flatzbourhof for medical attention.

The Telegram Home

John’s mother received a War Department telegram declaring him missing in action. She had not heard from her son in six months, but there had been news of him shortly before the telegram arrived. She had seen the portrait that Don Ornitz made at Mittersheim.

After leaving Mittersheim, Ornitz had turned in his exposed film and photo captions to his unit, the 166th Signal Photographic Company, which sent the material to an Army Pictorial Service laboratory in Paris. There, technicians developed the negatives and made prints for distribution.

Newspapers in the United States, including the one serving John’s hometown, received the photo and published it, correctly identifying him as the soldier pictured. Stars and Stripes also received the portrait, as well as a portrait of Hobart Drew. Both men served in the same tank company, and Ornitz photographed them the same day.

In London, the picture editor inadvertently mixed up the captions that resulted in the misprint. The newspaper published a lengthy retraction on February 14, 1945, and identified John Parks as the man in the photo and stated he was missing.

The retraction also included more information on Drew. The newspaper had tracked him down at a U.S. Army hospital near Oxford, England. The editor interviewed him there. Drew had been wounded in the leg by shell fragments before the Flatzbourhof battle. The newspaper published the Ornitz photo of Drew and a photo of him on crutches in a hospital robe. Drew knew little about John’s fate, and he told Stars and Stripes that he looked forward to seeing his buddy again.

In the United States, a reporter visited John’s mother in Mill Creek. The reporter found a heavyset woman in a baggy housedress. She wore a hearing aid in one ear and spoke about her sons John and Lester. Lester had flown 25 missions over Europe as a B-17 tail gunner and had returned to the United States in January 1944 to become an aerial gunnery instructor.

The proud mother told the reporter that she prayed her two sons would soon return to her. She clung to the hope that John still survived. The men he served with at Flatzbourhof knew the truth, none more so than his surviving crew members.

Russell Holland never came back to the unit after being wounded. Herman Coffy returned and finished out the war as a tank commander. On April 21, 1945, he signed an affidavit detailing the circumstances of John’s death. A week later, the commanding general of the 4th Armored Division sent a typewritten letter to John’s mother. The first sentence read, “By this time I am sure you have received the official notice of your son’s death.”

She had received no official word, at least until a telegram arrived several days later. Upon receiving the general’s letter, John’s mother wrote to her son’s friend John Fitzpatrick with whom she had recently corresponded. Fitz was convalescing from a mouth wound he suffered at Flatzbourhof.

The injured soldier responded: “Received your letter today, the one I was expecting, more or less. Maybe I shouldn’t tell you this, Mrs. Harness, but I knew John was dead all the while, but I was afraid to tell you. Please try to understand why I couldn’t tell you. My heart aches for you, and I had an awful time trying to write my previous letters to you.”

He went on to describe John’s death (based on information gleaned from Coffy and Holland). Before closing, Fitz added, “This is the hardest letter I have ever tried to write, Mrs. Harness. Maybe I am wrong in telling you what happened, but I figured you would want to know … Take good care of yourself and keep your chin up high. I am sure that’s the way John would want it.”

John Park’s Legacy

After the war, the Army sought to recover John’s remains and those of Ed Clark. In 1947, a War Department investigator visited Flatzbourhof, but he found no trace of John’s tank. Salvagers had already removed it from the battlefield.

The Army declared John’s remains “non-recoverable” in 1949 and informed his mother. Clark’s widow received the same news about her husband. The American Battle Monuments Commission later engraved their names on the Tablets of the Missing at the Luxembourg American Cemetery.

Fate dealt a losing hand to John Parks and all the missing men commemorated on the wall. Many of them passed through history leaving scant trace of themselves beyond a name carved in stone. John stands as an exception.

Though the cruel wheel of fortune burned him to ashes, the soldier from Mill Creek has never receded from sight. Publishers have reprinted his portrait countless times since the war, and the original negative now resides in the National Archives.

Across all the years, John still stares back at us. We cannot plumb his thoughts or know in any real sense the horrors he witnessed. But we can see the misery in his eyes, the eyes of a young man whose life was nearly behind him.

That is the legacy of John Parks.

rest in peace soldier, all patriotic Americans mourn your passing and honor your sacrifice to our country. You will not be forgotten, slow hand salute.

Very interesting and detailed story – thank god for our veterans and god rest the soul who fought, and many who died, that were part of the Greatest Generation.

I loved reading this story. Very well researched and written. John and many others paid the ultimate price for the freedoms many people enjoy today.

What an incredible story. Heroes in inferior equipment overcoming the odds. John Parks, RIP, you did your job and paid the ultimate price.

I enjoy the written report of these battels and the horrid details of their situation make a renowned impression on me. This World War II was massive and in my mind a terrible sacrifice for America and all these fine individuals. We lost thousands in Vietnam also, but the conditions were dissimilar. Thank you for these vivid accounts and God bless your continued success. Lt. Wm.W.Wilson A CO. Rifle Platoon leader 1st Cav. Div. Airborne, Airmobile

Excellent article and I enjoy reading every one. This particular account of John Parks hits home since my father served in the 4th Armored Division in the 22nd Field Artillery Battalion. As for many WW2 veterans he never spoke about his service at any length, however, several passages are familiar to me. Obviously the Battle of the Bulge, but also his time at Pine Camp, maneuvers in the Mojave Desert/Needles,CA, maneuvers on the Salisbury Plains in England, Arracourt, Singling, etc. He spoke highly of Creighton Abrams and never even saw Patton in his 4 years in the Army! What puzzles me about the article is the 4th’s departure from Boston on 12/29/43 on the Santa Paula. My research indicates the Santa Paula was sunk by a Japanese submarine in June of 1943. Maybe someone knows what ship the 4th sailed on to England. I would be interested to know.