By Jerome Baldwin

By the fall of 1916, Canadian soldiers fighting in the trenches on the Western Front had already distinguished themselves in battle. In 1915, they had staved off disaster at the Second Battle of Ypres when they plugged a gap in the Allied line after panicky French troops fled in the face of the war’s first poison gas attacks. Amid the noxious clouds of chlorine, the Canadians had improvised gas masks—urine-soaked handkerchiefs held over their faces—and saved the day. Now, in October 1916, the months-long disaster of the Somme was finally drawing to a close. The Canadian Corps alone had suffered 24,000 casualties. Their morale badly shaken, they were relieved to receive orders transferring them out of the battle area, but that relief was cut short when they saw that they were going into line opposite the notoriously dangerous Vimy Ridge.

Vimy Ridge

The Germans had taken the ridge in the first months of the war in 1914 and had managed to hold it ever since, despite repeated Allied attempts to capture it. Both the British and the French had tried to take it and failed, suffering heavy losses, and many on both sides considered it to be all but impregnable. Rising gently northwest from the Scarpe River valley, the ridge resembles a humpbacked whale, cresting at a height of 470 feet at Hill 145. About a mile north of Hill 145 was Hill 120, known as the Pimple. South of it was another hill, and the fortified positions of La Folie Farm, La Tuille, and Thelus, with Farbus on the reverse slope. While they held it, the Germans threatened the strategically important city of Arras and prevented the Allies from recapturing the Douai Plain and the coal-mining areas of Lens.

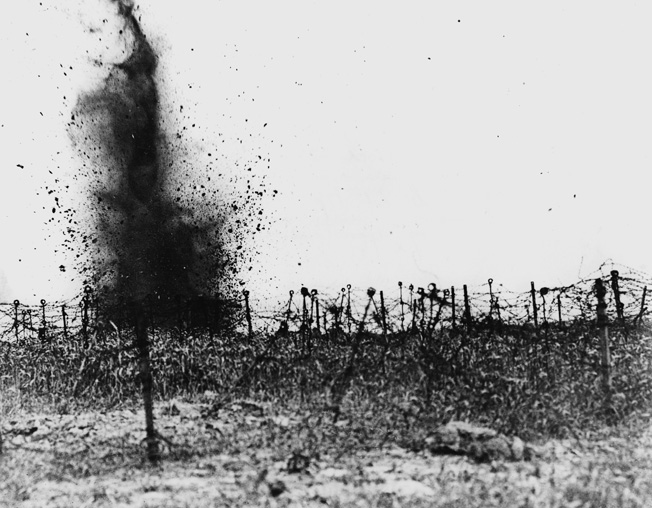

The ridge was defended by three divisions of the German Sixth Army, under Col. Gen. Ludwig von Falkenhausen. The Germans had constructed a defense in depth, with three belts of trenches and fortified dugouts, some complete with electricity and running water. Gun emplacements had been dug into the forward slope of the ridge, and there was artillery on the reverse slopes as well. Bristling with machine-gun nests housed in concrete and steel pillboxes, protected by massive rolls of razor-sharp barbed wire, and pitted with huge craters and countless shell holes for attacking infantry to move through, Vimy Ridge was an extremely tough nut to crack.

From the heights of the ridge, the Germans had a clear view for miles around, enabling their snipers to turn the entire area into a virtual killing ground. It was lethal to be out from under cover or concealment in the Canadian lines—even at night; the wily Germans simply sent up flares that turned night into day. The Germans were supremely confident that no one, certainly not the colonial troops from Canada, could take Vimy Ridge. One Bavarian soldier defiantly told his captors, “You might get to the top of Vimy Ridge, but I’ll tell you this: you’ll be able to take all the Canadians back in a rowboat that get there.”

“Welcome Canadians”

When the Canadians arrived, the Germans hoisted up an ironic sign that read: “WELCOME CANADIANS.” The carnage of the war and the grisly evidence of the savage fighting that already had occurred there were all around, with nearly every surrounding farm and town reduced to piles of rubble. No-man’s-land was an eerie moonscape of massive craters, littered with debris and the remains of thousands of men. Bones, grinning skulls, and entire skeletons in rotting uniforms of French blue or German gray lay everywhere, and the air was filled with the sour stench of death. Riven with destroyed trenches, the terrain was honeycombed with tunnels through the subterranean chalk surrounding the ridge, which was devoid of vegetation along its shell-blasted length. As the winter settled in and the temperature dropped to record-breaking lows, the Canadians endured all the miseries of trench life while the underground war continued. The troops were often hungry and always cold, but the war was going to heat up for them very soon.

A New Offensive

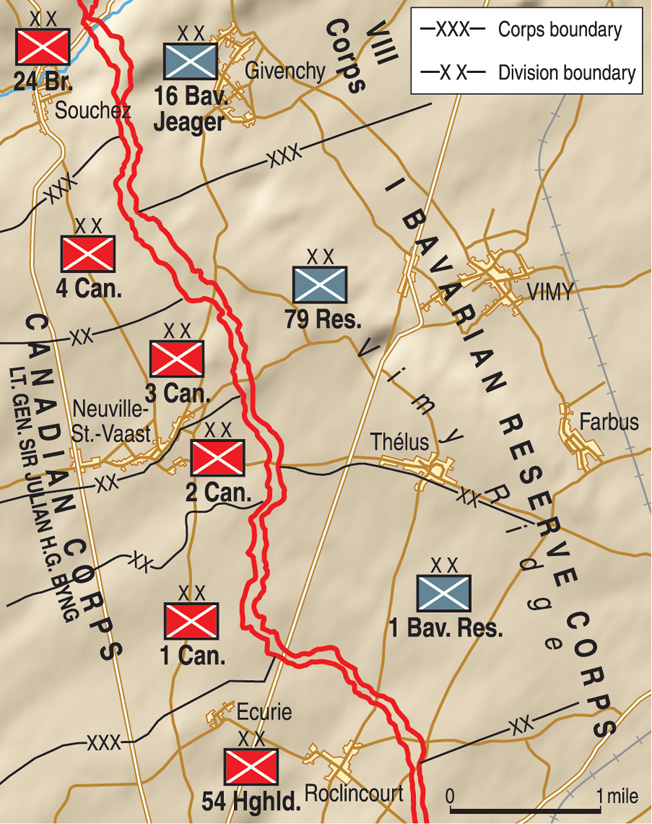

Championed by the new Allied commander, French General Robert Nivelle, the wildly ambitious plan for 1917 called for nothing less than to break the German lines, end the stalemate, liberate northern France, and win the war. While the French attacked at Chemins des Dames, farther south, the British were to begin an offensive between Givenchy in the north and Croisilles in the south. It would be the Canadians’ job to protect the northern flank of the British attack, and that meant taking the bastion at Vimy Ridge. Canadian Corps commander Lt. Gen. Sir Julian Byng was given the daunting task in mid-January; the high command wanted it done by April 1.

Lessons from the Somme: Practice Makes Perfect

Byng was an aristocrat, a career British Army officer, and a personal friend of King George V. An experienced officer, he had fought in South Africa and at Ypres, Gallipoli, and, most recently, the Somme before taking command of the Canadian Corps in September 1916. In many ways, Byng was a man ahead of his time. While many officers went nowhere near the front line, he often went right up to the forward trenches, inspecting defenses and talking to the men. In an era when it was unheard of to brief every man on an upcoming attack, Byng insisted that everyone, down to the private soldier, know the battle plan inside and out. He told his officers: “Explain it to them again and again. Encourage him to ask questions. Remember also, that no matter what sort of a fix you get into, you mustn’t just sit down and hope that things will work themselves out. You must do something in a crisis.” It was an unprecedented approach to command and training, and it would prove crucial in the upcoming battle.

Byng was determined that the bloodbath of the Somme not be repeated. During the agonizing winter months, glaring problems had come to the surface: not everyone had been briefed on the entire plan and not enough training had been conducted. The enemy’s barbed- wire installations had not been destroyed, and intelligence about enemy positions and strength had been lacking.

To get around the problems, Byng arranged for German defenses to be simulated in the rear using flags and colored tape to represent enemy strongpoints, roads, and trenches; their accuracy was based on trench raids and aerial photographs. Attacks were practiced repeatedly and the men learned the “Vimy glide,” how to advance safely behind a creeping barrage. The attacking infantry was synchronized with the artillery to move forward at a pace of 100 yards every three minutes, which would put the Canadians right on top of a German position so soon after the artillery barrage that the defenders would have no time to recover. Mounted officers carrying flags represented the creeping barrage as the men moved over the mock battlefield and learned the new attack strategy. Timing was everything. Byng told the men bluntly, “Chaps, you shall go over exactly like a railroad train, on the exact time, or you shall be annihilated.”

The Effectiveness of Trench Raids

During the fighting of the previous summer, thousands of British soldiers had been cut to pieces by German machine gunners while they got snarled on rolls of barbed wire whose five-inch barbs could ensnare a flailing soldier like a fly in a spider’s web. The wire was supposed to have been destroyed by Allied artillery at the Somme, but it had not—the shells exploded above the wire instead of on contact, and no one had gone out to verify if the wire had been destroyed prior to the attack. It was a case of criminal neglect that led to thousands of dead soldiers—the cream of British society and virtually the entire junior-officer class from the various elite universities. At Vimy Ridge, Byng intended to make sure that destructive No. 106 shell fuses were used; they did explode on contact and could blow pathways in the wire for attacking troops.

The fact that the shelling had been successful in destroying the wire was verified by trench raids that began at Vimy Ridge in December 1916. Armed with Lewis guns and Mills bombs, trench raiders provided invaluable intelligence from captured German documents and prisoners. When the raids began in December, they consisted of just a handful of men. Later, they would grow in size until well over 1,000 troops went over the top at any one time.

Besides gathering intelligence, the raids were used to familiarize the men with the territory they would be crossing on Zero Day. Each raid, in effect, was a dress rehearsal in working together. The raids had the added advantage of keeping the Germans in a constant state of tension, denying them rest and fraying their nerves. By the time of the actual attack on April 9, the Germans would be so exhausted that many of them were in no condition to fight.

The Cost of Preparation

Despite their advantages in intelligence gathering and experience, the raids were nevertheless costly—1,653 Canadians died at Vimy Ridge before the main attack even began, most of them in trench raids. But none was considered a real catastrophe until the largest raid was mounted on March 1, 1917, when 1,700 men of the 4th Division went over the top. Days prior to the raid, French civilians were inquiring about the upcoming attack. That should have raised a red flag in itself—if local civilians knew about the raid, the Germans too must have known. And they did. Some of those who had been taken prisoner had escaped the Canadians and made it back to their own lines with news of the buildup. Gas cylinders the Canadians were to use made a metal clanking sound as they were carried up to the line, alerting the Germans even more. Conversations in Canadian dugouts and tunnels had been overheard by Germans who had tunneled through the chalk close enough to eavesdrop. Some Canadian officers, realizing that another Allied disaster was brewing, tried to get the attack called off, but it was to no avail.

On the day of the raid, the Canadians unleashed deadly phosgene gas toward the German lines—delayed payback for the Huns’ poison-gas attack at Ypres—but some of the gas blew back into their own faces when the wind changed. Heavier than air, the gas also hung undispersed in the various shell holes and craters in which the attacking troops took cover, with predictably horrific results. The Germans had sited their machine guns to cover the gaps in the Canadian wire, conveniently marked with signs, turning them into kill zones. When it was over, there were over 600 Canadian casualties, many of them experienced officers and men whose absence on April 9 would be sorely felt.

“The Week of Suffering”

Despite the fiasco, the battle itself was fast approaching. Preparations continued with rising intensity; everyone knew the plan but not the date. In another unprecedented move, newly developed sound-ranging and flash-spotting techniques were used to determine the locations, with pinpoint accuracy, of German artillery on the ridge. British and Canadian guns targeted them and would soon blast them out of action. In the underground city the Canadians had created, work crews continued to chip away at the chalk, stringing communication cables back to the rear areas. Tools and ammunition were stockpiled in some dugouts, while others were prepared for everything from dressing stations to command posts. A light-railway system had even been built to bring the massive amounts of shells up to the hungry guns. Thirty miles of approach roads were constructed, two miles of tunnels were dug, and more than 40 miles of water pipes were buried to supply a subterranean city that was so large that the men frequently got lost in it, even with guideposts and street names.

During the final week before the attack, Canadian artillery and trench raiders turned the screws ever tighter on the Germans. Raids were conducted every night; the barrages became constant and much larger, with 2,500 tons of ammunition per day hurled at the Germans, who called the period “the Week of Suffering.” Heavy fire greatly impeded the enemy’s ration parties; creeping barrages and sudden intensification of fire on a particular section of trench line caused the Germans to raise an attack alarm, forcing them to stand to for an attack that never came and depriving them of much-needed sleep and food as they anxiously awaited the coming fury.

The Assault Begins

Finally, in the early hours of April 9, the assault troops moved into position. Some were in the forward trenches, others lying on their bellies in no-man’s-land, waiting. Thousands more were crammed into the dozen subways, dug into the chalk, which extended rearward. With just minutes to go, the muffled order to fix bayonets ran up and down the line. The metallic sound of thousands of bayonets being locked into place filled the pre-dawn darkness as a late-season snowstorm blew in. At precisely 5:30 am, a single big gun fired, followed by 900 more, creating a noise so loud that Prime Minister David Lloyd George could hear it all the way back in London.

Because it did not exactly parallel the Canadian lines, Vimy Ridge was 4,000 yards away at the southern end, narrowing gradually until only 700 yards separated the two armies at the northern end. As a result, the 1st Division, on the right flank under the command of Maj. Gen. Arthur Currie, had the farthest to go. The division was expected to secure the Farbus Wood on the eastern slope by early afternoon. The first objective was just beyond the German forward trenches, known as the Black Line on the maps the Canadians carried. Following behind the creeping barrage as they had been trained to do, the 2nd and 3rd Brigades reached the jumping-off point on schedule, signaling with flags to low-flying aircraft that they had arrived.

The Infantry Advance

After 38 minutes the barrage, which had shifted ahead 200 yards, began to creep forward again as the men set out for the Red Line, a German trench called the Zwischen Stellung by its defenders. It was now 6:55 am. Resistance was stiffening; men fell to German machine-gun fire, but others stepped in to take their places and the attack momentum never slackened. Pockets of enemy resistance were bypassed for the “moppers up” to handle later. Some machine-gun nests were put out of action by extraordinary acts of courage. Private William J. Milne of the 16th Battalion (Canadian Scottish) single-handedly took two out during the attack and was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.

The attackers reached the Red Line at 7:13—right on schedule. Once there, the 2nd and 3rd Brigades halted, dug in, and prepared to allow the 1st Brigade to pass through them and carry on the attack. By early afternoon the Canadians were safely in the Farbus Wood, with the shell-blasted village of Farbus securely in their hands.

Meanwhile, the 2nd Division, under Maj. Gen. Henry Burstall, also made good progress. Unlike the 1st Division, the 2nd Division encountered the heaviest fighting at the outset of the attack. German resistance lessened as they advanced farther east and fanned out as the front widened. With a wider front to cover, the Canadians required more troops, and the British 13th Brigade went with them. In all, some 30,000 British artillerymen took part in the Vimy attack, as well as infantry and pilots of the Royal Flight Command. One of the 2nd Division’s objectives was the hamlet of Thelus, a veritable haven for German snipers who used its cellars as cover. Now the Allied artillery zeroed in and blasted the village to ruins, ending the sniping. When the Canadians finally overran Thelus at 10:30, they found a German officers’ dugout complete with a fully stocked bar and a staff of five waiters.

The Essence of Speed

Despite the various warning signs, the Germans were surprised by the speed of the Canadian advance—some of the Vimy defenders were captured in their underwear. On the 1st Division front, attackers discovered a German dugout with meals still hot on the table, hastily abandoned by enemy officers. After subsisting for so long on bully beef and plum jam, the rich fare left behind by the Germans must have been the finest meal the fortunate Canadian soldiers ever tasted in their lives.

Exhausted and hungry, some of the Germans eagerly surrendered, and the trickle of prisoners quickly became a river. But there were many other veteran defenders who simply hid in their dugouts until the Canadians had passed, then emerged to shoot them from behind. Machine guns took a heavy toll on the attackers, their positions becoming easy to spot from the khaki-clad corpses that lay in front of them. To take them out, the Canadians used newly developed platoon tactics, attacking from three sides with Mills bombs and machine guns. They could not have known that they were using tactics their more mobile sons would use in the next war with the Germans.

The 3rd Division, under Maj. Gen. Louis Lipsett, moved quickly to take its objectives. The division had a shorter distance to cover and had only two enemy lines to reach, Red and Brown, before they would be on the eastern slope. After they had advanced nearly to the Brown Line, they began to take sniper and machine-gun fire from Hill 145 on their left. Some of the units there, such as the Black Watch from Montreal on the far left, were particularly hard hit. Something was definitely wrong on the neighboring 4th Division front.

Hill 145 Holds Out

Hill 145 was in the 4th Division sector, and it was vital that it be captured as quickly as possible. Under the command of Maj. Gen. David Watson, the 4th Division did not have the experienced officers and men it once had, owing to the raiding debacle of March 1. During the artillery barrage, the German trenches at the base of the hill were purposely not destroyed because one of the Canadian infantry commanders made the astonishing request that they be left intact for his men to use as cover from the fire expected from Hill 145. Subsequently, when the Canadians attacked, they ran into a wall of German fire that decimated some units, such as the 5th Battalion, which lost 346 men out of 400. While the 4th Division attack stalled, the advance on the far left moved ahead, passing between Hill 145 and the Pimple, both still in German hands. Right away, the Canadians started taking fire on both sides.

One of the officers in the thick of the fighting was Captain Thain MacDowell of the 38th Battalion, who would win one of four Victoria Crosses in the battle. Chasing after some fleeing Germans, MacDowell followed them through a dugout entrance and down a long stairway, where he found himself instantly enveloped in darkness. Continuing to advance, he turned a corner and came face to face with 77 Prussian Guards—a seemingly hopeless situation. Thinking quickly, MacDowell called over his shoulder to a nonexistent group of men, as though he was leading a large force (there were only two of his comrades behind him on the surface). The ruse worked; the Germans raised their hands in surrender. By taking them up in small groups, MacDowell managed to conceal the fact that he was virtually alone. MacDowell was luckier than Milne: he lived to receive his decoration and eventually became the only VC recipient at Vimy to survive the war. The other two with MacDowell were Lance Sgt. Ellis Sifton of the 18th (Western Ontario) Battalion and Private John Pattison, 50th (Calgary) Battalion.

The success of the attack remained up in the air. If Hill 145 held out until dark, the entire operation would be in serious jeopardy. Under cover of darkness, the Germans would have all night to bring up reinforcements. Hill 145 had to be taken quickly, but where were the men going to come from? Once again the losses of March 1 came into play—there were no men left to spare. The 10th Brigade was slated to attack the Pimple the next day and so could not be tapped. In desperation, the 85th Battalion was found.

The 85th Battalion

The 85th (Nova Scotia Highlanders) was an orphan battalion, not attached to any division. It had arrived in France only a month before and to date had been tasked merely with menial labor such as building roads and digging trenches. The battalion was referred to derisively as “Highlanders without kilts,” but now history had plucked them from obscurity to be the last hope of the Canadian assault on Vimy Ridge. Attacking directly up the hill into the teeth of the German defenses, the green troops of the 85th Battalion so shocked the enemy by the sheer audacity of their attack that the Germans panicked and ran until the entire section was in full retreat down the reverse slope. Behind them, the 85th dug in. It was truly a miraculous victory.

Capturing the Pimple

Throughout April 10 and 11, the Canadians consolidated their positions. There were still some fierce small-group clashes, and snipers picked off men unfamiliar with their new positions, but the fierce counterattacks for which the Germans were renowned never materialized. All along the ridge, the Canadians gazed in awe at the peaceful French countryside to the east, which the war had barely touched. There, life went on as it always had. Green fields, green trees, and intact buildings seemed like another world compared to the shell-blasted hell of devastation and misery just over the Canadians’ shoulders.

On Thursday, April 12, as another snowstorm kicked up, helping to blind the German defenders, the 10th Brigade of the 4th Division attacked straight up the Pimple and captured it in 90 minutes. With that charge, the Canadian victory was complete. Vimy Ridge would remain in Allied hands for the rest of the war. The price, as expected, was high. The Canadians suffered 10,602 casualties, including 3,600 dead. But the capture of Vimy Ridge cemented the fighting reputation of the Canadian Corps. German Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg called them without hesitation “the best of the English troops,” and British Prime Minister David Lloyd George wrote admiringly, “Whenever the Germans found the Canadian Corps coming into the line, they prepared for the worst.”

Painful Victories and Sustained Stalemate

The Canadian success at Vimy Ridge was followed by similar success to the south, where the British Third Army, led by General Sir Edmund Allenby, punched through German lines for 31/2 miles—a near-miraculous distance after years of snail-like advances on the Western Front. The exultant British prepared to exploit their new openings, but they were quickly disappointed in their hopes. Thanks to a voluntary withdrawal by other German troops just prior to the assaults, the German Sixth Army commander, Baron Ludwig von Falkenhausen, had ample reserves to staunch the bleeding. Despite inflicting some 75,000 casualties on the Germans—and suffering some 84,000 of their own—the British were unable to exploit the stunning successes of early April. The war settled back into a stalemated slugfest.

The disgraced architect of the Allied spring offensive, General Nivelle, was replaced by General Henri Pétain, the hero of Verdun, who returned to a defensive war strategy he summed up succinctly: “We must wait for the Americans and the tanks.” In the meantime, 54 French divisions mutinied and refused to obey orders; thousands more deserted. By the time the spontaneous revolt was quelled, more than 100,000 war-weary French soldiers were court-martialed, of whom 23,000 were found guilty. Officially, only 55 soldiers were executed by firing squads, although French officers in the field shot down untold numbers of their own men or sent them forward unsupported to die beneath German artillery barrages. Pétain assuaged the army by promising that there would be no more French offensives in the war.

More Canadian victories were to follow Vimy Ridge, at places such as Arleaux, Hill 70, and Passchendaele. All were costly. As the war drew to a close in 1918, the Canadians spearheaded the Allied advance known as the Hundred Days. After the victorious conclusion of the war, Canada was given a seat at the peace negotiations because of the performance of its troops in the Great War. A total of 60,000 Canadians died in World War I, one in 10 who served at the front, about the same number of men as the United States lost in Vietnam—all suffered by a country of only 12 million people.

The Legacy of Vimy Ridge

For Canadians, Vimy Ridge represented more than just the capture of an enemy stronghold on a snowy April morning in 1917; it was the place where Canada literally grew to manhood. Having been a self-governing nation for only 50 years, Canada suddenly emerged from the colonial shadows onto the world stage by gaining the greatest Allied victory to that point in the war.

Nearly 20 years later, in 1936, thousands of Vimy Ridge veterans and their families traveled back to the ridge to witness English King Edward VIII and French President Albert Lebrun dedicate a monument constructed atop Hill 145 after 11 years of work and $1.5 million in costs. The French, for their part, had not forgotten the Canadian triumph that day—thousands more of their own airmen and soldiers were also present at the dedication. In a token of deepest appreciation, 250 acres on the ridge and the surrounding acres were given to Canada by France. Still honeycombed with the ruins of trenches, tunnels, craters, and unexploded munitions, much of the site is closed to the public for safety reasons. It remains, however, a sliver of Canada to this day, a proud but costly reminder of the organized hell that was the Western Front nearly a century ago in World War I.

Originally Published February 2010

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments